1 Key Laboratory of Neuroregeneration of Jiangsu and Ministry of Education, Co-innovation Center of Neuroregeneration, NMPA Key Laboratory for Research and Evaluation of Tissue Engineering Technology Products, Nantong University, 226001 Nantong, Jiangsu, China

2 Radiation Physiology Laboratory, Singapore Nuclear Research and Safety Initiative, National University of Singapore, 138602 Singapore, Singapore

3 Department of Neurology, Affiliated Hospital of Nantong University, 226001 Nantong, Jiangsu, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Radiotherapy is one of the primary modalities for oncologic treatment and has been utilized at least once in over half of newly diagnosed cancer patients. Cranial radiotherapy has significantly enhanced the long-term survival rates of patients with brain tumors. However, radiation-induced brain injury, particularly hippocampal neuronal damage along with impairment of neurogenesis, inflammation, and gliosis, adversely affects the quality of life for these patients. Astrocytes, a type of glial cell that are abundant in the brain, play essential roles in maintaining brain homeostasis and function. Despite their importance, the pathophysiological changes in astrocytes induced by radiation have not been thoroughly investigated, and no systematic or comprehensive review addressing the effects of radiation on astrocytes and related diseases has been conducted. In this paper, we review current studies on the neurophysiological roles of astrocytes following radiation exposure. We describe the pathophysiological changes in astrocytes, including astrogliosis, astrosenescence, and the associated cellular and molecular mechanisms. Additionally, we summarize the roles of astrocytes in radiation-induced impairments of neurogenesis and the blood-brain barrier (BBB). Based on current research, we propose that brain astrocytes may serve as potential therapeutic targets for treating radiation-induced brain injury (RIBI) and subsequent neurological and neuropsychiatric disorders.

Keywords

- radiation

- astrocyte

- brain injury

- cognitive effects

- radiotherapy

Ionizing radiation is naturally present in the environment and cosmic rays but is also widely used for medical diagnosis and therapy. Cranial radiotherapy has been extensively employed to treat both primary and metastatic brain tumors by targeting and destroying cancer cells [1, 2]. Over the past two decades, the use of radiotherapy for brain tumors has significantly increased [3, 4]. During both fractionated partial-brain radiation therapy (PBRT) and whole-brain radiotherapy (WBRT), normal brain tissue is inevitably exposed to radiation, which can lead to radiation-induced brain injury (RIBI). This condition is associated with increased intracranial pressure [5], cognitive decline, mental health decompensation [3], progressive dementia [6], and secondary epilepsy [7]. Cognitive domains affected by RIBI include learning and memory, processing speed, attention, and executive functions [8]. Despite advances in radiotherapy technology, RIBI remains a serious, often progressive and debilitating, complication [9, 10]. Thus, there is an urgent need to mitigate and treat RIBI. An in-depth understanding of cellular responses to radiation exposure within the central nervous system (CNS) is essential for developing new therapeutic strategies to address this issue.

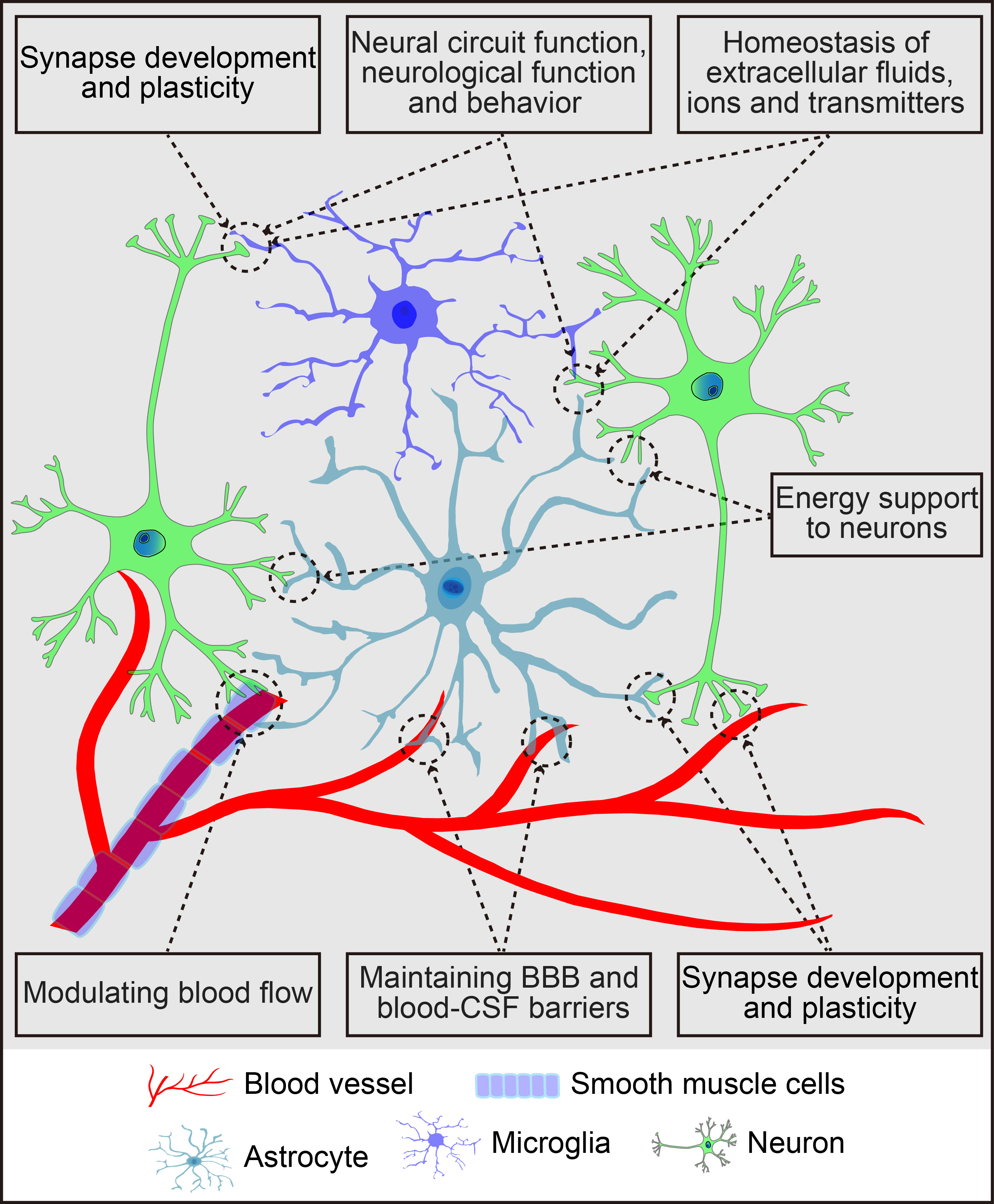

The brain parenchyma, often referred to as the “soil” of the CNS, comprises neurons, glial cells (astrocytes, microglia, and oligodendrocytes), and vascular cells such as pericytes and endothelial cells. Astrocytes, the most abundant glial cells, cover the entire CNS, playing vital roles in CNS health, development, and damage response. They communicate with neighboring cells, including neurons, microglia, oligodendrocytes, oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs), meningeal fibroblasts, perivascular cells, and various immune cells, through the release of signaling molecules. In a healthy CNS environment, astrocytes maintain extracellular ion, fluid, and neurotransmitter homeostasis [11], provide energy substrates to neurons [12], regulate cerebral blood flow [13], facilitate the drainage of interstitial fluid [14], and play key roles in synapse development and plasticity [15]. Their dynamic activities are crucial for neural circuit regulation, neurological function, and behavior [16]. Additionally, astrocytes support the integrity of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier (for details, refer to Fig. 1). Beyond their normal functions, astrocytes become reactive in response to CNS insults, including neurogenesis and synaptogenesis following brain injury. These reactive astrocytes respond to molecular signals from various cell types, releasing a range of signalling molecules that affect both neural and non-neural cells [17, 18, 19, 20]. Consequently, astrocytes play a central role in regulating the pathogenesis of brain disorders.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Schematic summary of the primary functions of astrocytes in the central nervous system. The figure was created using Adobe Illustrator software (2022 (3.0), Adobe Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). BBB, blood-brain barrier; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

Glioblastoma is the most prevalent, aggressive, and lethal primary brain tumor in adults, accounting for more than 60% of all brain tumors, and is categorized as a grade IV astrocytoma [21, 22]. Astrocytomas originating from astrocytes, primarily affect the normal brain function [21]. Combined surgical resection, chemotherapy and radiation therapy are effective and widely used treatments. However, glioblastoma almost always recurs, often exhibiting a more aggressive phenotype [23]. Radiation has dual effects on the tumor’s immune microenvironment [24, 25]. After radiation, the residual tumor cells were eliminated. Simultaneously, the tumor antigens and immune effector molecules were released, initiating the systemic antitumor immune responses. However, immune evasion of tumor cells was also promoted. Radiation regulated the expression of several immunosuppressive cytokines and chemokines, inducing many myeloid inflammatory cells to migrate to residual tumor areas. Vascular remodelling and DNA damage repair were thereby accelerated to promote tumor recurrence [26, 27]. In addition, radiation therapy promoted an immunosuppressive microenvironment to facilitate tumor regrowth by inducing astrocyte senescence [27]. However, the precise mechanism by which the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) factors mediate suppressive tumor immune microenvironment formation after irradiation remains unclear. Until now, radiation-induced changes in neurons [28, 29], microglia [30], and oligodendrocytes [31] have been well documented, but the functional changes of astrocytes in the radiation-induced brain damage are still not fully understood. Therefore, we summarized the radiation-induced protective or destructive effects on the brain astrocytes and highlighted the potential therapeutic approaches to target astrocytes to mitigate radiation-induced brain damage.

Radiation-induced histopathological changes in the brain exhibit significant individual variability influenced by several factors, including the specific brain region exposed to radiation, the diagnostic instruments used, the patient’s age, and the radiation dose administered. Notably, different brain regions demonstrate varying degrees of resistance to radiation damage. However, the underlying mechanisms remain inadequately understood, posing a fundamental challenge in radiation biology [32]. A substantial body of evidence indicates that the hippocampus is markedly more radiosensitive than other brain regions. Within the hippocampus, different subregions respond distinctly to radiation exposure. The cornu ammonis (CA), a non-neurogenic subregion, shows no detectable inflammatory changes following radiation exposure. In contrast, the dentate gyrus (DG), a neurogenic subregion, experiences a reduction in neurogenesis accompanied by glial activation and neuroinflammation. Furthermore, the effects of radiation on neurogenesis and neuroinflammation differ between adults and juveniles. This age-dependent variation in radiosensitivity is likely attributable to the proliferative capacity of the neural stem/progenitor cell niche [33]. To mitigate radiation damage to healthy tissues, radiotherapy is often delivered in smaller doses known as “fractionated” doses. This approach involves administering the total radiation dose in several smaller fractions over a treatment course that typically spans several weeks. The heightened radiosensitivity of the DG underscores the importance of protecting this region by minimizing both the total dose and per-fraction dose during brain radiotherapy. Such measures can help prevent potentially adverse effects associated with radiotherapy. Additionally, localized increases in activated microglia and reactive astrocytes may regulate neurogenesis and neuroinflammation dynamics [33].

The effects of prenatal irradiation on postnatal astrocyte genesis within the hippocampal formation depend significantly on the developmental stage of the irradiated brain. This influence may affect both the fate and molecular phenotypes of newly generated neurons during late developmental stages, similar to observations in the cerebral cortex [34, 35, 36, 37, 38]. While further research is necessary to elucidate radiation-induced regulatory feedback pathways governing astrocyte genesis post-birth, it is widely accepted that interactions among various cell types in the CNS establish the final proportions of neurons and glial cells within each brain region [39, 40]. To maintain a balance between neurons and glial cells, a reduction in astrogliogenesis must coincide with a decrease in neuronal proliferation within the hippocampal formation. Consequently, brain regions exhibiting severe neuronal impairment are expected to show lower rates of astrocyte proliferation [39].

Astrocytes play a crucial role in the brain’s response to neuronal loss following toxic insults [41]. When the brain undergoes irradiation, astrocytes become activated and undergo a process called astrogliosis to help repair damaged tissue [42]. For over two decades, the functional roles of reactive astrocytes, or astrogliosis, in brain injury have been a subject of debate [43, 44, 45]. During astrogliosis, astrocytes undergo significant changes, such as cell proliferation and hypertrophy at the lesion site [20]. These reactive astrocytes, marked by elevated levels of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), vimentin, nestin, transcription factors, growth factors, growth/differentiation factor 15 (GDF-15), signalling receptors, extracellular matrix components, inflammatory cytokines, and cell adhesion proteins, migrate to the injury site to form a “glial scar”, supporting tissue repair [46]. The glial scar formed by GFAP-labeled reactive astrocytes creates a boundary around the lesion, protecting healthy tissue from further damage [47]. This barrier may help to alleviate symptoms and improve survival rates in affected patients [48]. Reactive astrocytes also release various growth factors and cytokines that promote brain repair, stimulating additional trophic responses favorable for tissue recovery and remodeling. However, prolonged secretion of inflammatory molecules can become harmful, potentially exacerbating brain damage [49].

The glial scar has a dual effect: it physically separates injured tissue from

surrounding areas, preventing damage from spreading, but it also restricts axon

regeneration [46, 50]. Reactive astrocytes can be activated by various

mechanisms, including neuronal damage, neurodegeneration, amyloid-beta

(A

Following radiation exposure, elevated inflammatory cytokines and reduced

synaptic adenosine, along with persistent astrogliosis, are indicative of RIBI

and cognitive deficits [59, 60]. Additionally, microglia-mediated astrocyte

activation through inflammatory cytokines (e.g., C1q, IL-1

| Models | Radiation Type and dose | Time point | Astrocytes in DG | Inflammation | Neurogenesis & DNA damage | Reference |

| Male mice (2-month-old) | 0.1 Gy |

60 days post-irradiation | No change | No change | No change | [64] |

| 0.1 Gy |

60 days post-irradiation | GFAP+ cells increased | IBA1+ cells increased | DCX+ cells increased | ||

| 1 Gy |

60 days post-irradiation | No change | IBA1+ cells increase | DCX+ cells reduced | ||

| Fractionated low-dose radiation (FLDR): Male juvenile mice (age of P11) and adult mice (age of P56) | FLDR: 20 |

72 h after the last exposure | SDR: no chang | FLDR and SDR: IBA1+ cells increased | FLDR: DCX+ cells reduced | [33] |

| Single-dose radiation (SDR): adult mice (age of P56) | SDR (1 |

FLDR: GFAP+/S100 |

SDR: DCX+ cells drastically reduced | |||

| Adult male Beagle dogs (19.6–23.5 kg) establishing a preclinical spinal cord injury (SCI) model | Low-dose fractionated irradiation (LDI) of X-ray: 14 |

14 and 60 days post-irradiation | LDI reduced astrocyte activation and proliferation, GFAP+/Ki67+ cells were reduced | LDI reduced microglia activation and proliferation | LDI facilitated axonal regeneration after SCI | [65] |

| Mice at postnatal day (PD) 3 | 2 Gy X-ray at PD3 in mice | 1, 7, 21, and 90 days after irradiation (PD3+1, PD3+7, PD3+21, and PD3+90, respectively) | GFAP+ cells: increase at PD3+1; decrease at PD3+7 and PD3+21 | IBA1+ cells: PD3+1 and PD3+7, increase; PD3+21 and PD3+90, decrease | [66] | |

| p-P65/P6: PD3+7 and PD3+21, increase; PD3+1 and PD3+90, no change | SIRT1: PD3+21, increase; no change in other time points | |||||

| IL-1 |

||||||

| TNF- |

||||||

| F1 hybrids of a C57BL/6J female and a C3HeB/FeJ male were used as wild types, and heterozygous mutants, male and female at the age of 10 weeks ( |

whole body radiation at 0.063, 0.125 or 0.5 Gy | 24 months post-irradiation (p.i.) | GFAP/C3 double-positive astrocytes, no change | IBA1+ cells increased at the dose of 0.5 Gy | / | [3] |

| 3-D brain organoids induced from hiPSCs | 0.5 or 2 Gy of 250 MeV protons | 0.5, 24, and 48 hours post-irradiation | No changes in the astrocyte numbers at the 24-hour; reduced gene expressions of astrocyte lineage, mitochondrial function, and cell cycle progression by 48 hours | / | Oxidative stress, and DNA damage 48 hours post-irradiation | [67] |

| Male adult and juvenile mice (age P56 or P11 at start of low doses of ionizing radiation (LDR)) | LDR: 20 fractions of 0.1 Gy, for up to 4 weeks daily | 72 hours and 1, 3, and 6 months after LDR | The increased reactive astrocytes at 72 hours post-irradiation, but decreased reactive astrocytes at 1 and 3 months post-irradiation | The increased microglia numbers in 1 month post- irradiation in both adult and juvenile hippocampi | Reduced neurogenesis | [68] |

| Human SH-SY5Y cells exposed to |

10, 30 or 100 mGy |

6 days after exposure | Reduced GFAP and attenuated differentiation in 10 and 30 mGy treated group | / | The number of neurites formed per cell was significantly less | [69] |

| 6-month-old male mice | Whole-body irradiation at 50 cGy (5-beam simplified GCR spectrum 1H, 28Si, 4He, 16O, and 56Fe) | 3 months after irradiation | No significant changes | No significant change | No significant change but irradiated animals demonstrated a decline in their short-term memory capabilities and an absence of spatial memory retention on the fifth day of the probe trial | [70] |

| Wild-type (WT, Nox2 +/+) C57BL/6 mice or Nox2–/– (B6.129S6-CYBBM) knockout (KO) mice | Whole-body irradiation at a total dose of 0.04 Gy by LDR over a 21-day period | 1 month after 21-day hindlimb unloading (HLU); and/or LDR | Increased brain AQP4 staining was observed after LDR + HLU treatments in WT animals | / | / | [71] |

| Female mice (6-week-old) focally on osteolytic sarcoma cells inoculated in humeri | 6 Gy X-ray | 7 days post-radiation (day 17 post tumor implantation) | Decrease in astrocytes | Decrease in microglial cells and increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines (MCP-1 and TNF- |

/ | [72] |

| Astrocyte cultures from neonatal rat cortex | 4 Gy X-irradiation at a rate of 3 Gy/min | 12, 24, and 48 h following radiation | Suppressed astrocyte proliferation | Higher levels of p53 were observed | DNA damage | [73] |

| Young adult male mice | Whole brain irradiation by X-ray with 0, 2, 5, or 10 Gy | 6–48 h post-irradiation; | Apoptosis peaked 12 h after irradiation, and was dose-dependent. 48 h after irradiation, proliferating SGZ cells were reduced by 93–96% | IBA1+ cells increase | Reduced neurogenesis which was dose-dependent. No changes in astrocytes | [74] |

| And neurogenesis 2 months post-irradiation | ||||||

| 3D collagen-based cortical tissue model (CTM) | 5 Gy, |

24 h after treatment | The astrocytic processes were visibly decreased | / | DNA damage | [75] |

| Female rats (6–8-week-old) | Whole-body irradiation with 60Co |

0.5, 2, and 4 months after radiation | The activated astrocyte population was significantly more abundant in the LDR group compared to the HDR group. And A1-type astrocytes were activated in the LDR group | The activated microglia population was significantly more in the LDR group compared to the HDR group. Moreover, the LDR group had activation of M1-type microglia; conversely, the HDR group had activation of M1-type microglia and no other types | / | [76] |

| HDR: 30 |

DG, dentate gyrus; GFAP+, glial fibrillary acidic protein positive; IBA1,

ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1; IBA1+, IBA1 positive; DCX,

doublecortin; DCX+, DCX positive; SIRT1, Sirtuin 1; hiPSCs, human induced

pluripotent stem cells; MeV, megaelectron volt; Gy, gray; SH-SY5Y, human

neuroblastoma cell line; GCR, galactic cosmic radiation; SGZ, subgranular zone; CHOP, C/EBP homologous protein;

Reactive astrocytes may undergo astrogliosis or astrosenescence in response to

cytotoxic challenges [77]. Following radiation exposure, DNA damage occurs as a

primary intrinsic factor, resulting directly from radiation injury or as a

secondary consequence of free radicals and reactive oxygen species (ROS). A recent

study suggests that elevated methylation markers of astrocyte-derived

circulating free DNA may trigger cell death in astrocytes due to both immediate

and delayed radiation exposure, contributing to the pathophysiological mechanisms

of RIBI [78]. When DNA double-strand breaks are not repaired, cells may

experience apoptosis, senescence, genomic instability, or mutations. Cellular

senescence plays a crucial role in tissue injury following radiation exposure,

promoting chronic inflammatory responses that contribute to the side effects of

radiotherapy [79, 80]. Various pathways have been identified that trigger

cellular senescence in response to radiation [81]. Although senescent cells do

not replicate, they can secrete inflammatory factors that induce tissue damage by

evading clearance and persisting within tissues [82]. Astrocytes are particularly

sensitive to DNA-damaging agents following radiation exposure [77, 83]. Studies

have shown that astrocytes constitute the most abundant subpopulation of

senescent cells in irradiated brain tissues and exhibit variations in their

secretory phenotypes [27, 83, 84]. This is characterized by increased expression

of senescence-associated

The loss of homeostatic functions—such as extracellular energy supply and glutamate buffering due to high doses of radiation may be linked to neurodegeneration in the brain. High-dose radiation induces morphological changes and reductions in astrocyte populations that may result from premature astrosenescence driven by oxidative stress [3]. In contrast, low-dose radiation does not produce comparable harmful effects on astrocytes as seen with high doses. Irradiation during prenatal, postnatal, and early adult stages can exert lasting effects on glial cells and animal behavior. The impact of radiation exposure can be either damaging or beneficial depending on the dose administered. Astrocytes are particularly susceptible to senescence [83, 84], and the SASP is involved in neurodegeneration induced by aging or toxins within the brain [95, 96, 97, 98, 99]. Prior studies have shown that astrocytes represent the most abundant subpopulation of senescent cells in irradiated brains of both humans and mice. Moreover, radiation-induced astrosenescence can lead to the release of SASP factors that potentially stimulate tumor growth and invasiveness in syngeneic mouse models of glioblastoma [83, 84]. Therefore, astrocytic senescence significantly contributes to radiotherapy-induced neurodegeneration. Additionally, microglia and endothelial cells in irradiated human brains have also been found to undergo senescence, albeit to a lesser extent compared to astrocytes [84]. Further investigation into these processes is warranted.

Neurogenesis is known as a strictly determined process in which nerve cells are scheduled to be produced in the brain. If this process is temporarily or irreparably disrupted, it may result in a reversible or irreversible deficit in the neuronal population [100, 101, 102]. Among the neurogenic zones in the brain of adults, hippocampal neurogenesis is related to advanced cognitive function, particularly the processes of learning and memory and certain affective behaviors. In neurologically healthy humans, hippocampal neurogenesis of adults is abundant and seems to play a significant role in the plasticity of the hippocampus throughout life [103]. Neurogenesis in adults happens primarily in the subgranular zone (SGZ) of the DG in the hippocampus [103] and the subventricular zone (SVZ) of the lateral ventricles [104]. Substantial data demonstrates that new neurons originating from the SGZ and SVZ are effectively incorporated into the existing neuronal circuitry [103, 105, 106]. Considerable data show that newborn cells are very important, and have a close relationship with cognitive function and behavioral performance [107, 108]. Radiation impairs neurogenesis in the SGZ and SVZ and hinders the differentiation of neuronal progenitor cells (NPCs) into mature neurons in animals [74, 109, 110]. Similarly, neurogenesis is severely disrupted after radiation exposure in human patients [111]. Compared with neurons, glial cells have a more flexible generation program and keep their potential to transform, adapt, and proliferate to the pathological changes induced by radiation even in the adult brain [112]. Identified as dynamic regulators of neurogenesis [113, 114, 115], astrocytes in the SVZ and DG are highly specialized and regulate the proliferation and fate specification of NPCs [115]. The neurogenic cells are extremely sensitive to radiation, and the neurogenesis is decreased following the doses of radiation under the threshold for overt tissue damage [74, 109, 116, 117].

The reduced neurogenesis induced by radiation and likely the resulting cognitive deficit are significantly related to the neurogenic microenvironment [117, 118]. Among the microenvironment factors, oxidative stress can significantly affect neurogenesis, involving many reactive species regulating the function and fate of NPCs [119]. The CNS is inherently prone to oxidative stress for the comparatively low endogenous antioxidant defence [119, 120]. The sensitivity to oxidative stress of the CNS has been recognized as having a role in causing or contributing to multiple pathologic conditions [121, 122]. Radiation has been shown to induce an increase in ROS production, contributing to the spread of the lesion and the ultimate extent of brain damage [123, 124]. Elevated levels of ROS, coupled with early apoptosis, specific blocks in the cell cycle, and activation of functional cell cycle checkpoints, have been observed in radiated cultured hippocampal NPCs [125]. Sustained oxidative stress has also been shown in the irradiated brains of mice [126] and rats [127]. ROS may be crucial for the microenvironment to control NPC survival as well as differentiation and considerably contribute to reduced neurogenesis and cognitive deficits following irradiation [125]. Therefore, oxidative stress is an essential factor of the NPC microenvironment that has been demonstrated to alter neurogenesis, and inhibiting oxidative stress by the antioxidant enzyme superoxide dismutase (SOD) is one of the radioprotective approaches [128, 129]. The brain environment deficient of SOD and its downstream ROS promotes NPC differentiation toward an astrocytic lineage [129]. Thus, astrocytes are suggested to be more resistant to superoxide than neurons, resulting in improved long-term survival. Irradiation has little or no effect on newborn cells that differentiate to astrocytes. After irradiation, the ratio of new neurons to new astrocytes decreased significantly in wild-type mice but remained similar in the SOD knockout animals. The relatively more newborn astrocytes in the SOD knockout mice might promote the survival of newborn neurons after irradiation by oxidative stress and redox regulation, in light of the crucial role astrocytes play in neurogenesis [119, 130]. The potential effects of differences in the astrocytic cell population on neurogenesis after radiation, or whether these differences are simply indicative of a non-specific response or process caused by persistent oxidative stress, require further investigation.

Neuroinflammation is another brain microenvironmental factor which plays a critical role in neurogenesis after radiation [1, 33]. Mice with reduced neurogenesis have cognitive impairment after intracranial irradiation with 10 Gy [110]. Transplantation of neural stem cells to replace the lost hippocampal NPCs in mice following whole brain radiation partially rescues cognitive function, highlighting the contribution of NPC loss to cognitive deficits after irradiation [131, 132]. Numerous studies have aimed to clarify the mechanisms by which radiation reduces NPCs in the hippocampus [133, 134, 135]. A compelling hypothesis suggests that radiation triggers inflammation and damages the microvasculature in the hippocampal SGZ and SVZ, disrupting the microenvironment of progenitor cells and potentially inhibiting their differentiation into neuronal phenotypes. The interruption of signalling pathways within hippocampal neurons is understood to inhibit working memory, long-term potentiation, and synaptic plasticity [136]. Further influence on the signalling of hippocampal neuron may lead to NPCs differentiating to glial rather than neurons in this region [1, 74, 133]. Additionally, numerous studies have suggested that neuroinflammation, marked by an increase in activated microglia and astrocytes and variations in their activation states, can be both beneficial and detrimental to neurogenesis [74, 86, 109, 134, 135].

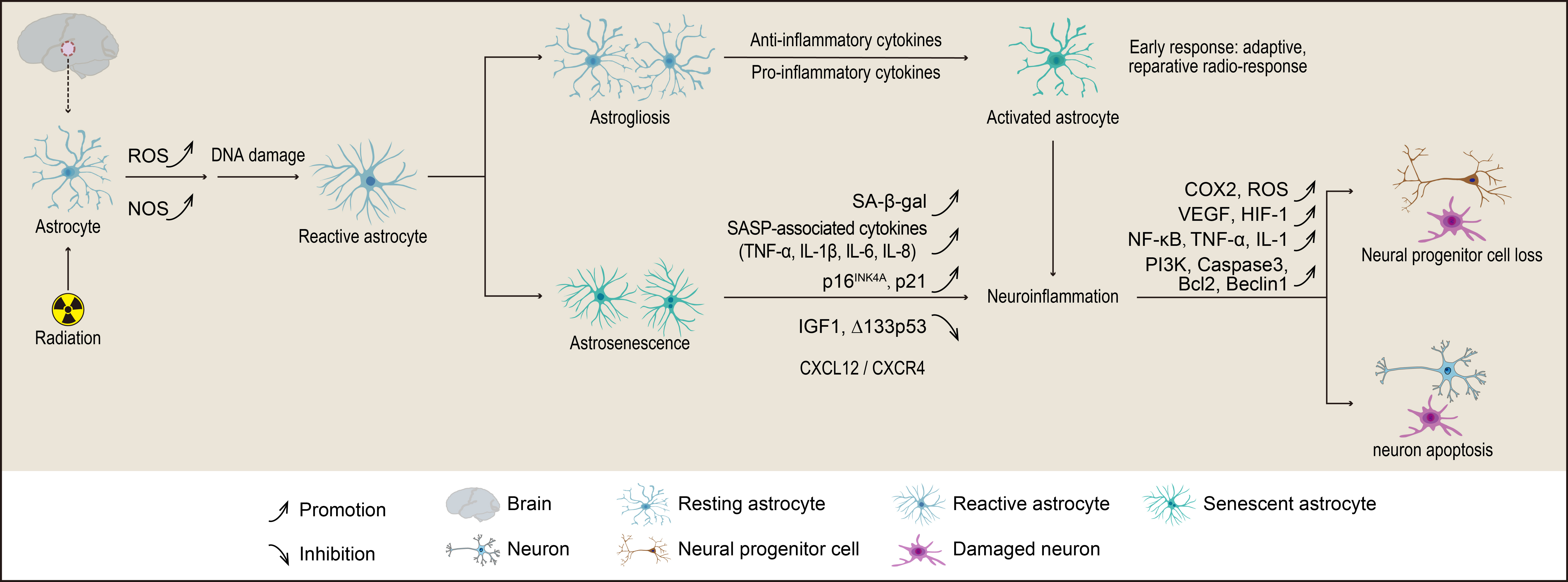

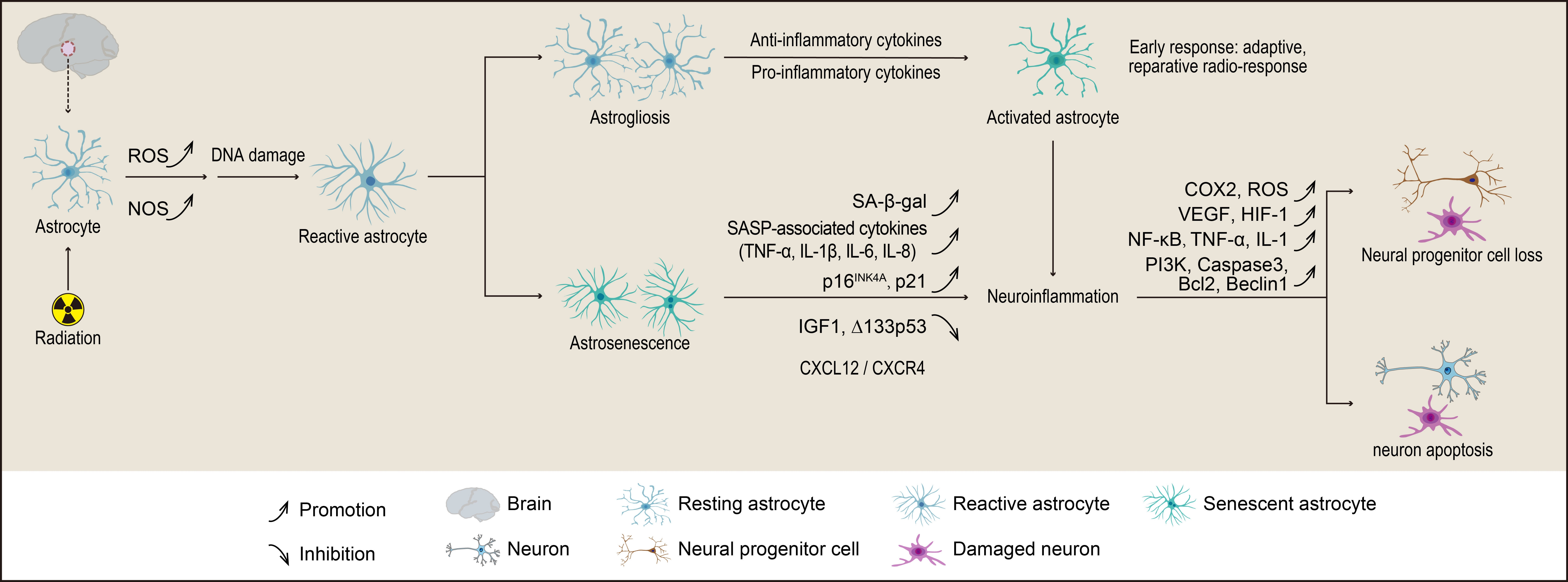

The complex pathological mechanisms underlying cognitive deficits in the hippocampus and the precise relationship between neurogenesis and neuroinflammation following radiation remain unclear. The studies suggest that the DG of the hippocampus is particularly sensitive to RIBI, likely due to the death of proliferating neural progenitors [33, 104, 107]. Moreover, the effects of radiation on neuroinflammation and neurogenesis differ between juveniles and adults, with this age-related radiosensitivity potentially linked to the varying proliferative capacities of the neural stem cell niche. Research has shown that a single dose of radiation has a more pronounced impact on the development of neuronal network architecture in preclinical models compared to repetitive low-dose exposures. Depending on the extent of neuronal damage caused by radiation, increases in activated microglia and reactive astrocytes regulate the dynamic processes of neuroinflammation and neurogenesis. Collectively, these findings suggest that radiation-induced hippocampal damage is primarily due to the reduction of proliferating neural progenitors, coupled with subsequent inflammatory responses from microglia and astrocytes aimed at repairing radiation-induced neuronal damage. Chronic neuroinflammation has been observed to persist for over six months, even after exposure to repetitive low-dose radiation [3]. This implies that even low single doses of radiation can lead to neuronal damage, neuroinflammation, and reduced neurogenesis in the neurogenic niche of the hippocampus. The changes and effects of astrocytes in the radiation-induced reduction of neurogenesis are illustrated in Fig. 2. Together, these findings emphasize the impact of radiation fractionation and underscore the importance of limiting radiation dose fractions to protect the vulnerable DG during clinical radiotherapy [32]. Therefore, reducing both the total radiation dose and dose fractions to the hippocampal stem cell niche is critical in protecting neurocognitive function in cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

The mechanisms by which astrocytes contribute to radiation-induced reductions in neurogenesis involve their transformation into either astrogliosis or astrocyte senescence (astrosenescence). Astrogliosis is characterized by hypertrophy, proliferation, and various molecular and functional changes in astrocytes. In contrast, astrosenescence is marked by a decline in normal physiological functions and an increased secretion of senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) factors, which ultimately impair neurogenesis. The figure was created using Adobe Illustrator software (2022 (3.0), Adobe Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). ROS, reactive oxygen species; NOS, nitric oxide synthase; CXCL12, C-X-C motif chemokine 12; CXCR4, C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4; IGF, insulin-like growth factor; COX, cyclooxygenase; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; HIF, hypoxia-inducible factor; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; Bcl2, B-cell lymphoma 2.

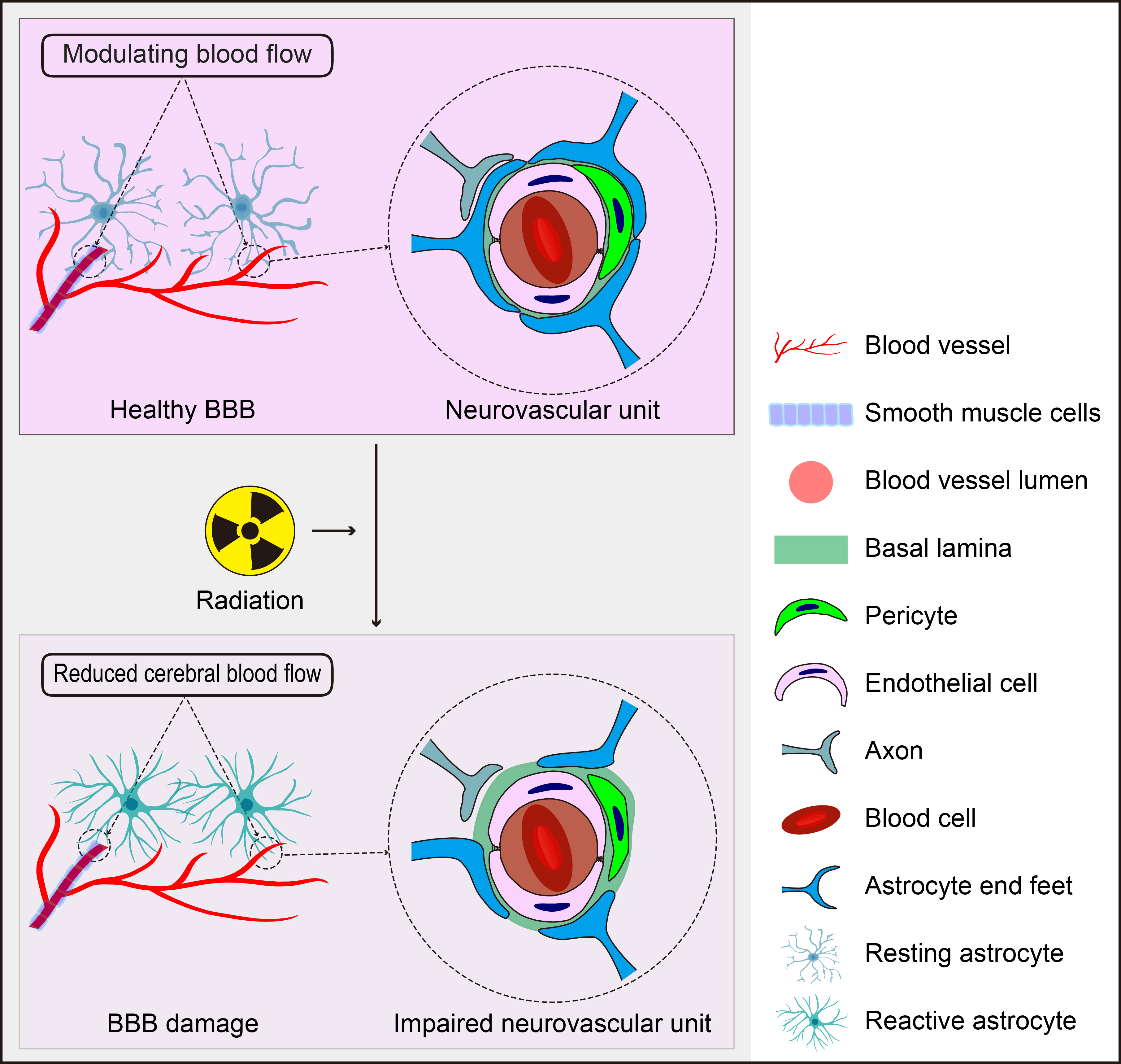

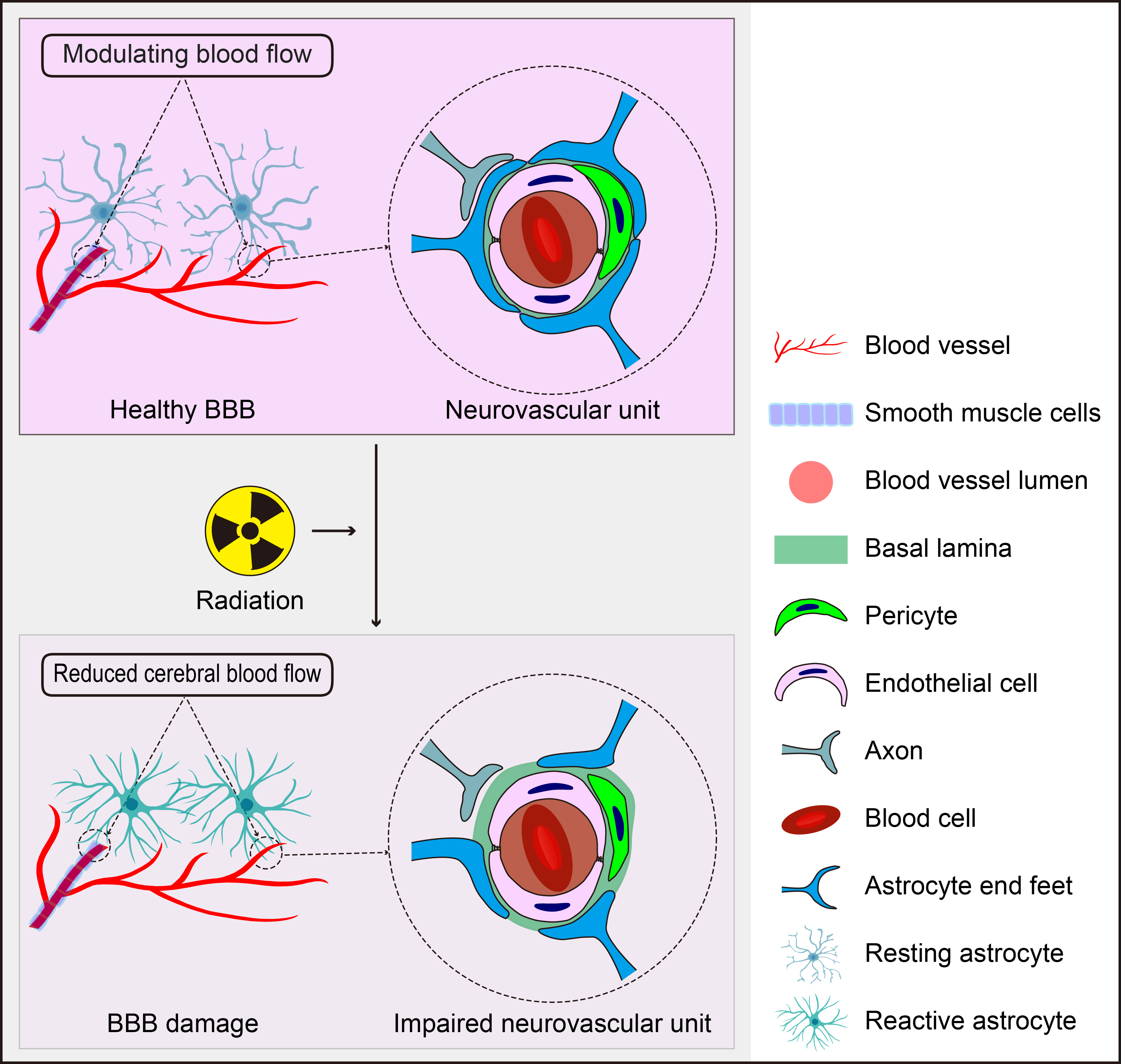

BBB is composed of endothelial cells (ECs), pericytes (PCs), the capillary basement membrane, and astrocyte end-feet [137]. Astrocyte end-feet constitutes 90–98% of the cerebral microvasculature and envelop the abluminal side of endothelial cells, playing a critical role in maintaining BBB integrity and tightness through various effector molecules [138, 139, 140]. Additionally, astrocytes facilitate intercellular communication between blood vessels and the neuronal network [141]. Pericytes, which are embedded in the capillary basement membrane, also contribute to BBB integrity. The BBB regulates the selective influx of ions, nutrients, and oxygen from the blood into the brain parenchyma while removing potentially harmful substances from nervous tissue. Its permeability is primarily controlled by tight junctions [142]. Astrocytes directly influence the tightness of the BBB; their end-feet form a crucial part of its structure and are closely associated with the outer surface of the vasculature [143]. Through tight junctions, astrocytes interact closely with both pericytes and endothelial cells, thereby sustaining the maintenance and dynamics of the BBB [144].

Changes in BBB integrity are pivotal in various brain neuropathologies, including neurological disorders, neurodegenerative diseases, stroke, and RIBI [145, 146, 147, 148]. Simulated deep space radiation has been shown to induce high vascular permeability, damage tight junctions, and cause oxidative stress along with the production of inflammatory cytokines in a human organ-on-a-chip model [149]. On day 1 post-radiation exposure, astrocytes trigger vascular leakiness. From days 1 to 7 following radiation, astrocytes become reactive and adopt an antioxidant, anti-inflammatory regulatory phenotype. The interaction between astrocytes and cerebral vascular endothelial cells may play a role in radiation-induced BBB injury. In animal models, senescence has been observed in endothelial cells after brain radiation exposure, believed to result from pro-inflammatory cytokines released by activated astrocytes [150, 151]. This release can further promote additional pro-inflammatory factors, upregulate adhesion molecule expression, and enhance ROS production [80, 152]. Radiation-induced senescence has also been documented in fibroblasts [153] and chondrocytes [154]. Given that reactive astrocytes are observed up to 7 days after irradiation, it is possible that initial endothelial responses to radiation mediate subsequent astrocytic responses, forming a bidirectional process. Astrocytes are considered a more appropriate target for developing cell-specific interventions due to their ability to limit endothelial injury induced by space radiation, particularly during the subacute phase of radiation exposure [149]. Therefore, astrocytes can play a dual regulatory role in response to radiation exposure: initially aggravating BBB permeability and subsequently providing neuroprotection by decreasing oxidative stress and the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines during the subacute stage.

The effect of astrocytes on BBB maintenance after radiation is illustrated in Fig. 3. However, the precise mechanisms mediating astrocyte activation in response to radiation—and their protective versus detrimental functions—are not yet fully understood. Irradiated single astrocyte cells do not trigger an increase in oxidative stress as seen in endothelial cells; instead, they tend to decrease levels of major pro-inflammatory chemokines such as IP-10 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1). Conversely, endothelial cells exposed to space radiation increase expressions of IP-10 and MCP-3, which may reduce inflammatory responses from astrocytes within a combined BBB model. Nevertheless, irradiated astrocytes can also induce cellular injury and decrease expressions of anti-inflammatory cytokines. This suggests that further investigation into the mechanisms involved in BBB protection regulated by astrocytes is warranted. Current findings indicate that astrocytes may play dual roles in response to radiation: acutely exacerbating BBB permeability immediately after exposure while subsequently promoting neuroprotection by reducing oxidative stress and secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines during the subacute stage [149].

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

The Role of Astrocytes in Radiation-Induced BBB Disruption. Astrocytes, positioned between neurons and cerebral vessels, are crucial for maintaining BBB homeostasis, regulating CBF, and supporting the function of the neurovascular unit. However, they also have the potential to negatively impact these processes in response to radiation. The figure was created using Adobe Illustrator software (2022 (3.0), Adobe Inc., San Jose, CA, USA).

Astrocytic responses [155], parenchymal and vasogenic damage [156, 157, 158], autoimmune response [159], and free radical overproduction [160] occur in brain injury after radiation exposure. Reactive astrocytes (astrogliosis) may suppress the regeneration of neurons and the growth of neurites [161], and provide a permissive substrate for the regrowth of axons [162] or support the integration of transplanted neural stem cells [163]. The hypertrophic astrocytes show a marked increase in the production of the intermediate filaments GFAP [164, 165]. Single or fractionated radiation-induced changes in the vasculature, glial cells, and hypoxia (or a combination of these changes) in the brain of rodents have been well-documented [166, 167, 168]. Deng et al. [160] investigated the time-dependent activation of astrocytes in irradiated brains of mice after X-rays and found that many different biochemical mediators coupled with their receptors, and downstream signalling pathways were involved in astrocyte reaction to brain injury, suggesting that regulation of these pathways may prevent brain injury after radiotherapy.

High-dose radiation induces the disruption of the BBB [169], which is shown in

the early and late stages after radiation exposure [170, 171, 172]. The pathological

changes include the loss of endothelial cells, impairment of the tight junctions,

dilation of vessels and wall thickening, and changes in vessel density and

permeability. Such alterations might eventually result in white matter necrosis

and ischemia at the late stage of RIBI [173, 174]. Astrocytes are crucial to

sustaining the BBB integrity and barrier tightness through effector molecules,

including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), hypoxia-inducible

factor-1

Angiopoietin-2 (Ang-2) is classified as a growth factor of the angiopoietin-Tie

signalling pathway, which is a vascular-specific receptor tyrosine kinase pathway

and is a principal pathway associated with angiogenesis. As a potential mediator

between VEGF and microvascular injury, Ang-2 might act as a new target to

interfere with RIBI [185]. Similar to VEGF, as an angiogenic factor,

platelet-derived growth factors (PDGFs) are demonstrated to play important roles

in RIBI [179, 186]. PDGF is an ingredient in the whole blood serum purified from

human platelets [187]. In both mice and humans, the PDGFs consist of four

ligands, PDGF-A, PDGF-B, PDGF-C, and PDGF-D, and two receptors, PDGFR-

In addition to VEGF, CNS insult-induced reactive astrocytes can release many

protective factors, including Ang-(1-7), glial-derived

neurotrophic factor, sonic hedgehog, apolipoprotein E, retinoic acid, and

insulin-like growth factor-1. These protective factors alleviate the permeability

of BBB and improve BBB dysfunction after brain injury [195, 198]. Ang-(1-7) is

shown to prevent inflammatory response in the rat primary astrocytes by

regulating MAPK signalling after radiation [199]. The renin-angiotensin system

(RAS) blockers prevent cognitive dysfunction and regulate neuroinflammation after

radiation exposure [200]. These blockers may inhibit neuroinflammation by

increasing the concentrations of Ang-(1-7). Inhibiting Ang II, a

pro-inflammatory peptide of the RAS, was also shown to reduce inflammation and

prevent cognitive dysfunction against radiation [201]. Therefore, reducing Ang II

as well by increasing Ang-(1-7) levels by RAS blockers can inhibit inflammation

and prevent cognitive impairment against radiation. Preclinical studies also

indicate that blockade of Ang II by an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) or an

angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) reduces inflammatory responses

[200], prevents the activation of activator protein-1 (AP-1) and NF-

Astrocytes function as a cellular link between blood vessels and the neuronal circuitry, and maintain brain vascular integrity, support neuronal metabolism, and perivascular clearance [206]. Aquaporin-4 (AQP4), a type of water channel protein, is highly expressed in the extended end-feet of astrocytes, which promotes the perivascular clearance via the glymphatic system [207]. AQP4 is demonstrated to contribute to the resolution of peri-tumoral brain edema in human glioblastoma multiforme after combined chemotherapy and radiotherapy [208, 209]. However, the role of astrocyte end feet and AQP4 is not fully understood in the regulation of the solute transport within parenchyma extracellular spaces [210]. It is suggested that radiation-induced chronic inflammation can result in microglia phagocytosis of astrocyte end-feet, leading to impairment of BBB function [211, 212].

Reactive astrocytes show substantial heterogeneity at multiple levels during in vivo reprogramming for CNS repair in response to acute trauma, or chronic neurodegenerative disease [213]. The shift from excessive astrocytes to neurons might be viewed as a promising therapeutic strategy for the treatment of neurodegenerative disease and acute trauma [214, 215]. Strikingly, Neurog2 was found to induce the shift from astrocytes to neurons in the damaged region of the spinal cord. In contrast to the indirect shift from astrocytes to neurons mediated by Sox2 [215], Neurog2-induced reprogramming of the direct conversion has a better performance in efficiency and neural maturation, thereby suggesting Neurog2-induced neuronal cells may be used in the reconstruction of damaged neural circuits in the near future [216].

Radiation has been reported to induce neuroinflammation via the activation of glial cells [190, 217, 218]. Activated astrocytes were found in the brain at 90 days after the treatment with fractionated radiation [219], and an activated microglial response was observed at 6 months after fractionated radiation [220]. Furthermore, inhibition of astrocyte proliferation has been showed to affect BBB integrity [221, 222]. The activated astrocytes were observed 60 days from the start of radiation. Astrogliosis, while not a direct marker of inflammation, is related to or is a byproduct of inflammation in the brain in response to radiation. Irradiated microglia caused the activation of astrocytes by the secretion of Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), a metabolic product of the cyclooxygenase2 (COX-2) enzyme, which also plays a role in brain injury [223]. Irradiated astrocytes act as phagocytes to supplement microglial phagocytic activity in the CNS inflammatory responses [224, 225]. COX-2 augments the responses of a significant number of inflammatory agents determined, but also to repress the activation of at least two different chemokines in CNS injury after radiation [226]. These results suggested that targeting astrocyte COX-2 activity might be a new anti-inflammatory approach to treat RIBI for patients receiving radiotherapy. Notably, current studies indicate that COX-2 inhibitors can increase tumor radiosensitivity by intervening the angiogenesis signalling pathway [227, 228, 229, 230]. These results suggest that COX-2 from astrocytes may modulate the neuroinflammation in the brain after radiation exposure, and its inhibitors may be used for the treatment of CNS inflammation induced by radiation [226].

Radiation induces the activation of glial cells and increase of pro-inflammatory

cytokine expressions, which have been considered as the effectors of gliosis

following radiation [164, 231, 232, 233]. Activated astrocytes contribute to RIBI by

releasing cytokines such as IL-1, VEGF, HIF-1, and TNF-

Some chemokine networks, like the C-X-C motif chemokine 12/C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCL12/CXCR4) axis, are also found to be

upregulated by tissue inflammation after radiation exposure. Radiation-induced

hypoxia may mediate the cell-cell interactions among microglia, reactive

astrocytes, and macrophages around the necrotic core of the brain. Both

angiogenesis and inflammation in the brain after radiation might be induced by

HIF-1

Networks of glia-glia and glia-neuron interactions have been recently viewed as novel therapeutic targets for neurological disorders [250, 251]. Insights into the microglia-astrocyte network in neuroinflammation induced by radiation could be essential for understanding RIBI, and other complex neuronal diseases. Abundant in the brain, astrocytes play key roles in modulating neuronal function and cerebral blood flow (CBF) [252]. Astrocytes can secret neurotrophic factors to regulate the growth and survival of developing neurons, and increase of neurotrophic factors in astrocytes exhibits neuroprotection in brain disorders induced by low-intensity pulsed ultrasound stimulation [253]. Astrocytes are radiosensitive [83, 152, 254], whereas mature neurons are radioresistant [174]. The incredibly harmful effects of whole brain radiation on cognitive function are attributable, at least partially, to the radiation-induced phenotypic and functional changes of astrocytes [84]. Furthermore, evidence shows that astrocytic alterations induced by radiation may enhance neuronal excitotoxicity [254], impair the vital function of astrocytes in the modulation of regional CBF [83], and associate with BBB disruption [255]. It has been proposed that enhancement of neuronal survival and neurogenesis, and inhibition of neurotoxic microenvironment are common strategies to ameliorate cognitive dysfunction in patients receiving brain radiotherapy. Notably, drugs that are normally used in other neurological diseases have recently been repurposed for the treatment or prevention of RIBI, and several clinical trials are underway.

The functional correlation between astrocytes and neurons can be assessed by the generation and propagation of stimulus-induced intercellular Ca2+ transients and waves [256]. In cultured astrocytes and multiple excitable cell types, radiation was shown to alter Ca2+ uptake, endoplasmic reticulum function and/or gap junctional communication [257, 258, 259]. The increase of astrocytic cytosolic Ca2+ can mediate many cellular events, including gliotransmitter release from peri-synaptic astrocytic processes, as well as changes of the resistance vessel diameter at perivascular end-feet by regulating the release of vasoactive mediators [260, 261, 262]. Importantly, astrocytes are combined to form a gap-junction-coupled syncytium to support localized Ca2+ signals to be spread to adjacent cells. This connectivity is also critical for the spreading of metabolic substrates such as glucose and lactate to supply neuronal activity [263]. Behaviorally relevant changes in astrocyte Ca2+ signalling have been shown to be involved in neurodegeneration by preclinical studies [264, 265, 266]. A causal link between compromised astrocytic Ca2+ signalling and cognitive and behavioral impairment has been established by studies on transgenic animal models [265, 266, 267]. Despite these advances, the effects of radiation on astrocytic Ca2+ signalling and gap junctional coupling need more investigations.

It may be essential to prevent or alleviate indirect neuron damage after radiation by pharmacological intervention of microglial activation. However, such approaches might concurrently inhibit the direct neuroprotective properties of microglia-derived factors. Therefore, more in-depth exploration is necessary to reveal the functional importance of microglial activation and gliosis throughout radiation therapy. Since radiation-induced changes are at the multicellular levels and affected by multifactorial processes, the present review work suggests that the network of microglia-astrocyte interactions may serve as a novel therapeutic target for the treatment of RIBI, as supported by a previous report [223].

Cellular senescence is considered an effective treatment target for RIBI because

the senescent cells can accumulate and induce damage to the brain after

radiation. Recently, p53 isoforms,

RIBI is a complex, dynamic process that involves multiple brain cell types, including neurons, astrocytes, endothelial cells, oligodendrocytes, microglia, and neural stem cells. At the molecular level, oxidative stress and neuroinflammation triggered by radiation activate diverse signalling pathways in the brain. These processes may lead to telomere shortening in cells such as astrocytes, endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and chondrocytes, contributing to accelerated brain ageing. RIBI can lead to progressive cognitive decline, sometimes resembling dementia-like symptoms. It also shares pathological features with age-related neurodegeneration, including inflammation, chronic oxidative stress, and reduced neurogenesis. Research on the pathogenesis of RIBI has largely focused on neuron and neural progenitor cell loss, particularly regarding its impact on learning and memory impairment. However, the role of astrocytes during radiation exposure remains less understood. Astrocytes undergo significant structural and functional changes, including entering reactive states (astrogliosis and astrosenescence) that promote neuroinflammation and oxidative stress in response to radiation. Reactive astrocytes release various molecules including chemokines, cytokines, and proteases which can exert both pro- and anti-inflammatory effects, making astrocytes key players in both the detrimental and beneficial responses to RIBI and subsequent cognitive impairment. Enhancing our understanding of reactive astrocyte-related neuroinflammation, BBB disruption, reduced neurogenesis, and increased SASP could open new avenues for therapeutic strategies to address RIBI. With the growing use of computed tomography (CT), radiotherapy, radiopharmaceuticals, hospital nuclear waste stockpiling, and the potential threat of nuclear terrorism, a deeper understanding of astrocytes’ roles in RIBI specifically related to neuroinflammation, BBB damage, impaired neurogenesis, and neurotoxic SASP is crucial for developing protective therapies. Moreover, while most studies on radiation-related astrosenescence have focused on high-dose irradiation, further investigation into low-dose and low-dose-rate irradiation-induced astrosenescence is needed. Emerging technologies such as spatial transcriptomics and single-cell sequencing can help clarify the molecular mechanisms behind radiation-induced pathophysiological changes in astrocytes, paving the way for more targeted interventions.

RIBI, radiation-induced brain injury; BBB, blood-brain barrier; SASP, senescence associated secretory phenotype; BMs, Brain metastases; WBRT, whole brain radiotherapy; PBRT, partial-brain radiation treatment; CNS, central nervous system; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; IL-6, interleukin 6; ROS, reactive oxygen species; NOS, reactive nitrogen species; OPC, oligodendrocyte progenitor cells; CA, cornu ammonis; DG, dentate gyrus; BDNF, brain derived neurotrophic factor; GDF-15, growth/differentiation factor 15; A

CW: conceptualization, investigation, writing - original draft, writing - review & editing. XF: conceptualization, investigation, writing - original draft. YS: conceptualization, investigation, writing - original draft, writing - review & editing, supervision. FT: conceptualization, investigation, writing - original draft, writing - review & editing, supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This study was supported by National Research Foundation of Singapore (Block grant) to FT and National Natural Science Foundation of China (81970432) to YS.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.