1 Department of Neurology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, 400042 Chongqing, China

Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia and is characterized by the excessive deposition of amyloid-β (Aβ) plaques and the formation of neurofibrillary tangles. Numerous new studies also indicate that synaptic damage and loss play crucial roles in AD and form the basis of cognitive impairment. In recent years, synaptic-related proteins have emerged as important biomarkers for the early diagnosis of AD. Among these proteins, neurogranin (Ng), a postsynaptic protein widely present in the dendritic spines of the associative cortex in the brain, plays a significant role in memory, learning, synaptic plasticity, and long-term potentiation (LTP). This review aims to reveal the link between Ng and AD, as well as the potential for the diagnosis of AD, the prediction of the development of the disease, and the identification of a therapeutic target for AD.

Keywords

- Alzheimer’s disease

- synapse

- neurogranin

- biomarkers

- cognitive function

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and related dementias affect approximately 50 million people worldwide [1]. AD is one of the most prevalent neurodegenerative disorders globally and is characterized by manifestations of memory loss and cognitive impairment. The pathological hallmarks of this disease include the accumulation of extracellular amyloid-

Synapses are important components of neurons and essential structures for neural network connections, and there is a fundamental tenet in neuroscience in which synaptic function is fundamental to cognition. The hypothesis that synaptic damage or loss serves as an objective manifestation of neurodegenerative changes, most relevant to the decline in cognitive abilities observed in AD, is widely accepted. This concept is supported by clinical, postmortem, and nonclinical evidence [9]. The study indicates a reduction in cortical synaptic density of 25% to 30% in AD patients, with the synaptic density per neuron decreasing by 15% to 35% [10]. The idea that synaptic changes modulate information storage gained popularity in the mid-20th century with Hebb’s postulation that synapses between neurons that are simultaneously active undergo strengthening, contributing to the learning process [9]. The discovery of long-term potentiation (LTP) by Bliss and Lomo [11], as well as the plasticity of hippocampal synapses in memory formation by Takeuchi and colleagues [12], further emphasized this concept.

Synaptic dysfunction and loss are closely associated with the pathological cognitive decline experienced in AD [13, 14, 15]. Most studies to date indicate that mechanisms such as amyloidosis, neuroinflammation, and oxidative stress can lead to synaptic injury, suggesting that synaptic loss may be a downstream effect of amyloidosis, neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, and other mechanisms in AD [9, 16]. Biomarkers of synaptic damage reflect the consequences of disease-induced synaptic injury and loss in the brain. The injury and loss of synapses mirror the cumulative effects of various pathological substrates in AD, making them potentially optimal surrogate indicators of AD progression in clinical and radiological contexts [8, 17].

Many researchers have applied proteomic analysis to identify synaptic biomarkers for AD. Numerous studies have identified various potential synaptic biomarkers, including growthassociated protein 43 (GAP-43), neurogranin (Ng), synaptosome-associated protein of 25 kDa (SNAP-25), synaptoagmin-1, neuronal pentraxin 2 (NPTX2), neurexins, and synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2A (SV2A) [18, 19].

A recent study revealed that AD patients had higher concentrations of 14 synaptic proteins than non-AD participants did. Compared with other neurodegenerative diseases, AD patients presented with particularly elevated levels of synaptic proteins, with SNAP-25, 14-3-3 zeta/delta,

Neurogranin is a postsynaptic protein found in the dendritic spines of postsynaptic neurons and consists of a 78-amino acid peptide [24]. It is expressed predominantly in the associative cortex regions of the brain and plays a crucial role in LTP [25]. Among these synaptic-related proteins, Ng is essential for memory, learning, synaptic plasticity, and LTP [26]. It is considered to reflect synaptic degeneration [27, 28] and has the potential to predict cognitive decline in AD [29, 30, 31, 32, 33]. Ng is believed to be AD specific, as its CSF levels are higher in AD patients than in those with other forms of dementia and neurological disorders [22, 23, 34, 35]. It holds promise as a significant biomarker for the early diagnosis of AD. A variety of synapse-associated proteins are increased or decreased in AD, but most of them are not specifically increased or decreased in AD. Compared with other synapsis-associated proteins, Ng is the only postsynaptic protein at present, and these studies have used the specific mechanism of Ng in AD. In addition, the studies mentioned above have also shown that Ng is increased in AD and is specific in AD. Therefore, CSF Ng may be the best CSF biomarker for synaptic loss or dysfunction in AD patients.

Based on current research, synaptic damage represents an early manifestation of AD. Among numerous synaptic proteins, Ng has been extensively investigated as a specific biomarker for AD. To increase our understanding of the precise role played by Ng in AD, this article presents a comprehensive review encompassing Ng’s physiological mechanisms, involvement in AD processes, diagnostic efficacy, and potential therapeutic targets. The aim is to provide a thorough understanding of Ng.

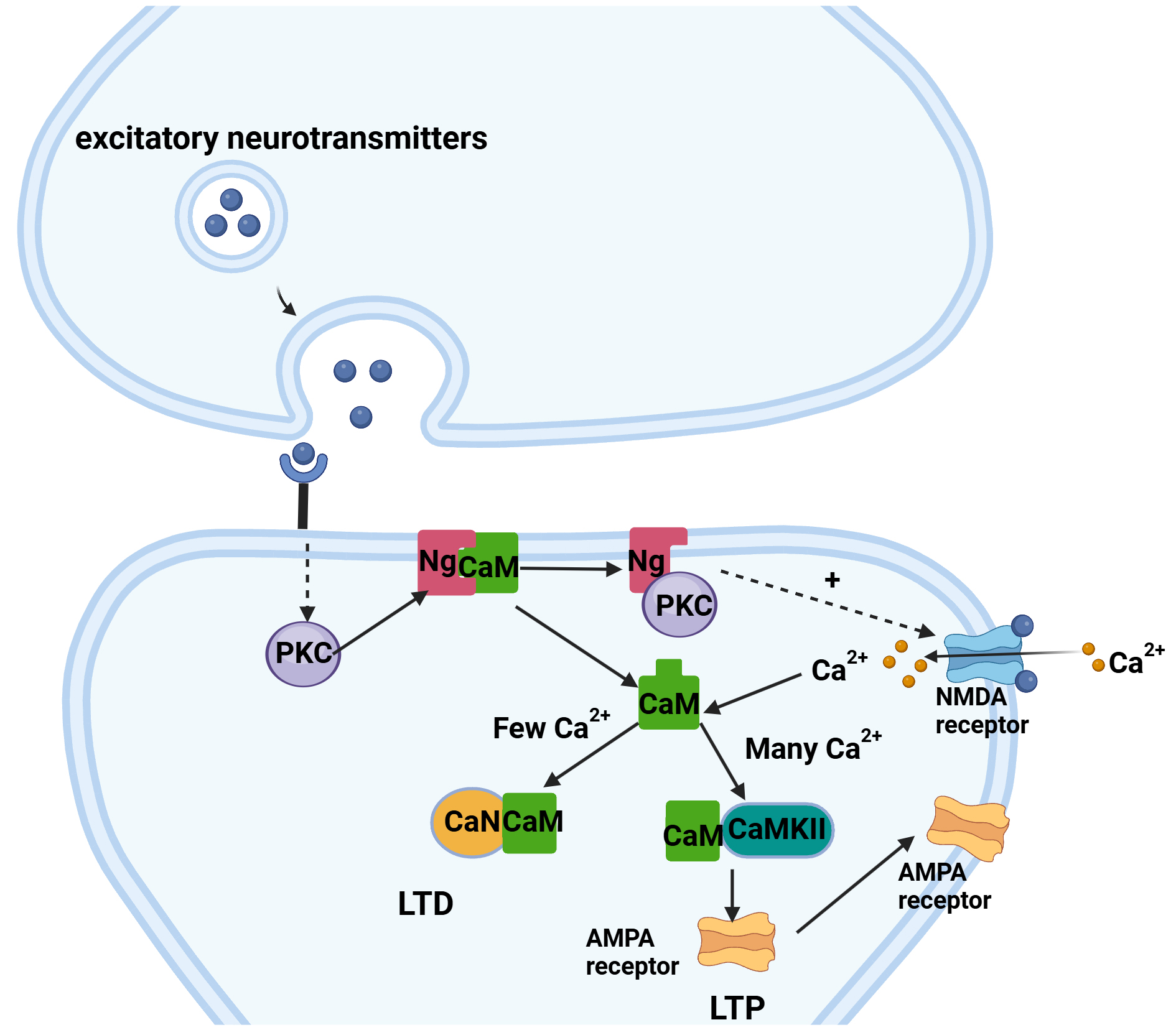

Ng is the most abundant postsynaptic calmodulin binding protein (CaMBP) and is an essential regulator of LTP and long-term depression (LTD) [36, 37]. LTP involves persistent strengthening of synaptic connections between neurons, playing a crucial role in the formation of long-term memories [38]. Impaired brain function is associated with insufficient induction and shorter maintenance of LTP, which is crucial for the generation of new connections between neurons [39]. LTD is induced by low-frequency stimulation (LFS) in vivo, resulting in weakened connections between synapses and a continuous decline in synaptic efficacy [40]. In the signalling pathway, Ng binds to calmodulin (CaM) through its intact IQ (AAAKIQASFRGHMARKKIK) [41] motif, limiting the interaction of CaM with other calmodulin-binding proteins (CaMBPs) [36]. Ng can target CaM to the postsynaptic membrane, increasing the sensitivity of CaM to calcium ions through the positioning of CaM. This, in turn, fine-tunes the regulation of LTP and LTD through the modulation of calcium ion/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) and the CaM-dependent protein phosphatase calcineurin (CaN) [42, 43]. Ng primarily localizes near the postsynaptic density, and this spatial positioning may allow preferential activation of targets, such as CaMKII, which are required for LTP induction [36].

A study indicates that a rapid and relatively large increase in the calcium ion concentration (several micromolar) within a short duration (seconds) activates CaMKII, leading to the induction of LTP [36]. In contrast, a modest increase in calcium activates only CaM, which in turn regulates LTD through the activation of CaN [44]. In its nonphosphorylated state, Ng binds to apo-CaM through its IQ motif, conferring the potential ability to isolate, localize, concentrate, and/or control the availability of this regulatory protein near the synaptic membrane [37, 45]. The increase in the synaptic calcium ion concentration also depends on the activation of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs). Ng recruits Ca2+/CaM signals to the postsynaptic region, where Ng enhances NMDAR-mediated synaptic transmission [36]. In the signalling pathway, protein kinase C (PKC) phosphorylates Ng, reducing its ability to bind to CaM. This allows CaM to activate CaMKII for an extended period, a potentially critical event for LTP [46]. Calcium binding to CaM enables it to activate CaMKII, which phosphorylates alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid glutamate receptors (AMPARs), allowing these receptors to move to the synapse. The localization of AMPARs in the membrane provides evidence for LTP [36, 41]. Additionally, an increase in local calcium ions can dissociate CaM from Ng [42, 47]. Therefore, an intact IQ motif and the ability to bind to CaM are essential for Ng’s involvement in LTP. The entire process is summarized in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Ng biological pathways. The binding of calmodulin (CaM) to calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) in the presence of a large amount of Ca2+ activates the alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid glutamate receptor (AMPAR) to complete long-term potentiation (LTP), and the binding of CaM to calcineurin (CaN) in the presence of a small amount of Ca2+ completes long-term depression (LTD). This figure was drawn using Biorender (https://www.biorender.com/). Ng, neurogranin; PKC, protein kinase C; NMDA, N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptor.

In mouse models, the hippocampal Ng concentration decreases with age and is associated with central nervous system functional impairments [48]. Nakajima et al. [49] conducted behavioural studies on Ng gene knockout mice, revealing phenotypes related to hyperactivity, spatial learning deficits, impaired social skills, motor dysfunction, and altered anxiety levels. In the CaMKII-TetOp25 mouse model (Severe Synaptic loss and Brain atrophy induction model), Ng levels in the CSF increase during neurodegeneration induction, whereas Ng levels in the brain decrease, suggesting that CSF Ng is a biomarker for synaptic degeneration [50]. In many postmortem human samples, research has revealed that Ng gene (NRGN) expression is negatively correlated with amyloid and tau protein pathology in the cortex, as well as with functional clinical dementia rating (CDR) scores, demonstrating an association with the neuropathological diagnosis of AD [51].

The relationship between Ng and A

Recent studies have indicated that, in the preclinical stages of AD when soluble A

A

Tau is a microtubule-stabilizing protein, and the phosphorylation of tau protein is considered one of the reasons for the formation of neurofibrillary tangles in AD [74]. When tau becomes excessively phosphorylated, it shifts from microtubules, leading to microtubule instability and disruption of neuronal transport mechanisms [75]. CSF t-tau is considered a marker of neurodegeneration, reflecting the intensity of neuronal damage, whereas CSF p-tau is a marker of phosphorylated tau found in neurofibrillary tangles, representing tau pathology. Ng is a neuron-specific postsynaptic protein and a marker of synaptic integrity and function [76]. Synaptic dysfunction is believed to occur before neuronal degeneration and death [77], as evidenced earlier, with an increase in CSF Ng preceding changes in p-tau. Additionally, a study by [78] has indicated a strong correlation between t-tau, p-tau, and Ng, especially in individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and AD. On the one hand, synaptic loss or impaired function may further affect the transport of microtubules in neurons. On the other hand, A

Inflammation is another common feature in the pathology of AD, and an epidemiological study suggests that long-term use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can reduce the risk of AD [2]. Neuroinflammation is a process that primarily involves microglia and astrocytes and is essential for healthy brain function [83]. In the context of AD pathology, neuroinflammation is driven mainly by activated microglia, which stimulate astrocytes, triggering a cascade of inflammatory responses that ultimately lead to synaptic loss and neuronal death [84, 85]. One of the most extensively studied inflammatory factors is chitinase-3-like protein 1 (CHI3L1), a protein primarily expressed by astrocytes in the brain and known as YKL-40 in humans [83]. Several studies have reported elevated levels of YKL-40 in AD patients [34, 83, 86]. While Hellwig et al. [34] reported no correlation between YKL-40 and Ng in AD patients, a recent study by Connolly et al. [83] suggested a correlation between Ng and YKL-40 in AD patients. In the brain, YKL-40 levels in the cerebrospinal fluid are elevated in several central nervous system (CNS) infectious and noninfectious diseases such as stroke, viral encephalitis, traumatic brain injury, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, multiple sclerosis, and AD [87, 88, 89]. The area under the curve (AUC) of YKL-40 as a biomarker for AD is 0.66, indicating that YKL-40 is a relatively nonspecific marker that is strongly influenced by patient comorbidities [34]. This may also explain why there are some contradictory data regarding the correlation with YKL-40. Further research is needed to understand the relationship between YKL-40 and Ng.

Multiple studies have consistently demonstrated the involvement of CHI3L1 in amyloid plaque formation, phosphorylated tau protein accumulation, and alterations in synaptic plasticity [90, 91, 92]. However, in addition to AD, the expression of CHI3L1 is also linked to other neurodegenerative disorders [93, 94, 95]. Recent research has revealed that a key regulator of the inflammatory state of the CNS, C-X3-C motif chemokine ligand 1 (CX3CL1), is significantly elevated in AD patients. The levels of Ng are also significantly correlated with both AD and MCI patients [83]. This may be attributed to the importance of CX3CL1/C-X3-C motif chemokine receptor 1 (CX3CR1) signalling in microglia for synaptic plasticity and neural regulation. The significant correlation between CX3CL1 and Ng in AD may be because CX3CL1 can inhibit the maintenance of LTP, reduce spontaneous glutamate release and postsynaptic glutamate currents, and promote the decay of hippocampal synaptic plasticity. It can also inhibit glutamate-induced calcium influx, especially in hippocampal neurons [96, 97, 98].

Relevant study indicate that Ng hydrolysis may be associated with AD. Compared with that in the control group, the ratio of peptide segments to full-length Ng increases in the parietal and temporal cortices of AD patients [99], suggesting that protein hydrolysis of full-length Ng occurs during synaptic degeneration. Mass spectrometry detection in CSF from AD patients revealed that endogenous Ng fragments represent approximately half of the C-terminus, and all fragments lack the IQ structural domain except for one [78]. Moreover, a study suggests that C-terminal fragments are not generated through extracellular protein degradation in CSF but are released from degenerating synapses in the CNS during the progression of the disease [76]. In the brains of AD patients, the activity of calpain-1 increases [100], and animal experiments have also demonstrated the cleavage of Ng by calpain-1, with cleavage sites either within or in proximity to its IQ structural domain. The protease prolyl endopeptidase (PREP) may also participate in further cleavage of Ng [101]. A proteomic study of isolated brain extracts revealed increased levels of

A recent study revealed that the gene expression of chitinase domain containing 1 (CHID1) is downregulated in the brains of AD patients and that the expression levels of CHID1 are positively correlated with those of Ng in both normal control and AD groups [105]. Therefore, in the pathogenesis of AD, the CHID1 gene may interact synergistically with the Ng gene. Multiple reports have linked the apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotype to synaptic function [106]. A study suggests that in the MCI group, CSF Ng levels are significantly greater in APOE

In a postmortem study, Ng levels were found to be lower in the hippocampal region and frontal cortex of AD patients, including those with early-onset AD (EOAD), suggesting its association with synaptic loss and neurodegeneration [27]. A recent autopsy revealed that in cases of intermediate AD, neurons in the CA2 and CA3 regions of the hippocampus exhibit a more rounded morphology, with Ng distribution near the cell body. In contrast, control cases present with Ng in neurons and prominent apical dendrites in the CA2 and CA3 regions of the hippocampus [108]. A study has indicated the specificity of Ng for AD diagnosis. In a study of patients with AD, frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD), Lewy body spectrum of disorders (LBD), and healthy controls, researchers reported that the expression of a synaptic protein was increased in biomarkers specific to AD [109]. These biomarkers include neurogranin and

First, changes in blood neuron-derived exosome synaptic protein biomarkers caused by AD were validated, and the biomarkers in blood exosomes could be used to distinguish patients with AD, control patients, and patients with mild cognitive impairment (aMCI). Among the exosome proteins, Ng showed the highest accuracy in distinguishing AD patients from aMCI patients and control groups [113]. Recent study has also yielded similar results, showing significant differences in all plasma neuron-derived extracellular vesicle (NDEV) biomarkers between the control group and individuals with AD. Compared with those in the control group, the plasma levels of Ng are lower in patients with mild to moderate AD, and the levels of Ng in plasma NDEV increase with the severity of AD and are associated with cognitive and functional decline [114]. Similar to a previous study on Ng in plasma NDEV, this finding can distinguish control subjects from those with mild to moderate AD as well as individuals with MCI, demonstrating high sensitivity [115]. However, a recent study suggested that Ng may not be specific to AD, as CSF Ng does not show a specific increase in clinical or confirmed AD patients. Notably, there was a significant difference in Ng levels between the high-Tau AD group and the AD group and non-AD dementia group [116]. Ng may also be an indicator of disease progression in AD, as previous studies have shown that high tau levels in AD patients can lead to the stabilization of Ng.

Several proteins in CSF have been reported as potential biomarkers for AD diagnosis, but fewer markers are associated with the progression of AD. Current research indicates that Ng, a synaptic protein, has significant potential as a biomarker for the progression of AD. In the early stages of AD, particularly MCI, elevated levels of Ng in CSF predict the rate of future cognitive decline [30, 78, 117]. Additionally, Ng levels are associated with future hippocampal atrophy and cortical glucose metabolism reduction, especially in patients with positive amyloid-

In a study by Kvartsberg et al. [78], the Cox proportional hazards model predicted the conversion from MCI to dementia, with a hazard ratio of 12.8 (95% CI, 1.6–103.0; p = 0.02). Moreover, baseline Ng was highly correlated with an annual decline in mini-mental state examination (MMSE) scores. A meta-analysis of 13 high-quality evidence studies suggested that CSF Ng could predict declines in MMSE scores in patients with MCI associated with A

The level of neuronal granule protein in synapses decreases before the loss of synapses, indicating that the loss of neuronal granule protein is not only related to synaptic loss. In recent study investigating AD-specific mutant variants, five components have been validated [111]. One component primarily loads on Ng and exhibits weaker loadings on tau indicators, but it is not associated with dementia symptoms. This component is referred to as the NonAD synaptic function. However, the aforementioned study was limited to cross-sectional analysis and did not incorporate longitudinal analysis to investigate gene effects [79]. In conclusion, Ng could serve as a viable target for the treatment of AD. Research has demonstrated that Ng can repair A

Dysfunction, loss, or damage to synapses can lead to cognitive decline. Synaptic proteins can serve as indicators of synaptic status, and Ng is widely present in the cerebral cortex, where it participates in signalling pathways related to LTP and LTD. Therefore, Ng may reflect the functional state of synapses and cognitive changes. In the context of AD, cognitive decline is associated with synaptic damage, making Ng one of the most promising synaptic proteins as a potential AD biomarker. Numerous studies on Ng in AD have demonstrated a clear upwards trend in its levels in the CSF of patients with MCI and AD. However, further research is needed to establish Ng as a diagnostic criterion for AD or for differentiating AD from other types of dementia and neurodegenerative diseases.

Currently, there are limited treatment options for AD, most of which are symptomatic. Several experimental treatments, including those targeting Ng, are in the early stages of development. Numerous studies have also suggested that increasing Ng levels can improve cognitive function in AD patients. The mechanisms underlying the reduction in Ng in the cortical regions of the brain in AD patients remain unclear and warrant further investigation. Therefore, therapeutic approaches targeting Ng require additional research.

The direct mechanism by which Ng is reduced in AD is still unclear. As mentioned earlier, studies have shown that changes in Ng may occur before significant synaptic damage occurs, and animal experiments have shown that knocking out the Ng gene can affect cognitive function. However, this does not necessarily indicate an independent mechanism unrelated to A

XZ conceived the project, carried out analysis of previous topics, and wrote the preliminary draft. XJJ conceived the project. HZ contributed to the conception of the study, design of the content framework, final manuscript preparation, and project supervision. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.