1 Department of Psychiatry, The Affiliated Wuxi Mental Health Center of Nanjing Medical University, 214062 Wuxi, Jiangsu, China

2 Department of Psychology, The Affiliated Hospital of Jiangnan University, 214062 Wuxi, Jiangsu, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) patients exhibit difficulty in forgetting negative material, which may result from specific impairments in memory and attention. However, the underlying neural correlates of the corresponding cognitive deficit have not been elucidated. The present study investigated the electrophysiological characteristics and differences, using event-related potentials (ERPs), between MDD patients and healthy controls (HCs) in an emotional directed forgetting task (EDF) with negative and neutral images.

A total of 26 MDD patients and 28 HCs were recruited for the current study, all of whom were clinically evaluated using the Hamilton Depression Scale. All participants were subjected to ERP measurements during the EDF task, and behavioral data and ERP components were analyzed.

HCs had higher hit rates than did MDD patients; more false alarms occurred in MDD patients than in HCs, and higher false alarm rates occurred with negative images than with neutral images. The reaction times were also longer for MDD patients than for HCs. Larger image-evoked P2 amplitudes and smaller image-evoked N2 amplitudes occurred in MDD patients, whereas they had higher image-evoked late positive potential (LPP) amplitudes both in negative and neutral emotional conditions than the HCs. MDD patients had higher cue-evoked N2 amplitudes and lower cue-evoked P3 amplitudes, elicited by the Remember cue, than the HCs. The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (24-item edition) scores were positively correlated with the LPP amplitudes that were evoked by negative images in a central location.

Based on these results, we concluded that poor attentional recruiting and allocation, memory inhibitory deficits, and difficulties in memory retention may contribute to the poor performance in the EDF task in MDD patients. The observed ERP patterns provide valuable insights into the neural mechanisms underlying the EDF task in MDD and underscore the potential of EDF as an assessment tool for cognitive and emotional dysregulation in MDD.

Keywords

- emotional directed forgetting task

- event-related potential

- major depressive disorder

- neural mechanism

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), one of the most prevalent mental health conditions globally, has profound effects on cognitive functions [1]. Research into the cognitive aspects of MDD has been extensive and continues to evolve, uncovering critical insights that are pivotal for both diagnosis and treatment strategies. Cognitive deficits in MDD encompass a wide range of functions, including attention, executive function, memory, and processing speed [2]. One study has consistently demonstrated that individuals with MDD exhibit significant impairments in these areas [3].

Emotional directed forgetting (EDF) is a cognitive process task in which individuals selectively remember or forget emotional information, often influenced by an instruction either to Remember or Forget [4, 5]. This phenomenon provides insight into how emotional valence and cognitive control mechanisms interact to manage memory storage based on the relevance or potential harm of the material. Research results have indicated that emotional content, especially negative emotional content, is more resistant to directed forgetting, suggesting a protective mechanism for salient or threat-related information [6]. The underlying neural substrate involves the prefrontal cortex and the amygdala, areas associated with executive function and emotional processing, respectively [7]. Studies often utilize the item-method directed forgetting paradigm, in which subjects are presented with items followed by cues to either remember or forget each item [4, 5, 6]. The effectiveness of directed forgetting highlights its potential therapeutic applications in managing psychological conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder, in which maladaptive memory processes are a core feature [8].

Neuroimaging research on EDF has significantly advanced our understanding of the neural mechanisms underlying the ability to manage the retention and forgetting of emotional information selectively. This line of research focuses on the neural correlates and circuitry involved when individuals are tasked with forgetting or remembering emotional stimuli. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies have consistently highlighted the role of the prefrontal cortex in EDF, particularly in the exertion of cognitive control over emotional memories [9, 10]. The prefrontal cortex is implicated in the top-down regulation of memories, especially when individuals are instructed to forget emotionally charged information. Activation in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, for instance, is often associated with the successful forgetting of unwanted memories, reflecting its critical role in implementing strategic forgetting [11]. The amygdala, known for its pivotal role in emotion processing, also plays a significant role in EDF [12]. A neuroimaging study has indicated that the interaction between the amygdala and the hippocampus is crucial, particularly in the encoding and retrieval of emotional memories [13]. Reduced amygdala activity is observed during the successful forgetting of negative emotional stimuli, suggesting a modulation of emotional reactivity that facilitates forgetting.

Event-related potentials (ERPs) are electrophysiological responses recorded from the brain, by means of electroencephalography (EEG), that are directly related to the processing of specific sensory, cognitive, or motor events. The technique involves measuring the brain’s electrical activity in response to a particular stimulus or event, and capturing fluctuations in voltage that occur at specific time intervals after the stimulus, which are believed to reflect different aspects of brain processing. Studies utilizing ERPs have provided insights into the temporal dynamics of EDF [14, 15, 16]. These studies highlight early posterior negativity (EPN) and late positive potential (LPP) as significant ERP components involved in emotional processing and memory control. The EPN is linked to the initial emotional reaction to stimuli, whereas the LPP is associated with sustained attention toward emotionally salient information.

Recent advancements have also included the use of resting-state fMRI to explore the functional connectivity patterns that might influence EDF capabilities. One study suggested that greater intrinsic connectivity within the fronto-parietal network is associated with better performance in directed forgetting tasks, underscoring the importance of network-level dynamics in cognitive control processes [17].

In the context of MDD, the study of EDF offers significant insights into the interplay between affect regulation and memory processes. MDD is characterized by pervasive mood disturbances, typically skewing towards persistent negative affect and impairments in cognitive functions, including memory. Research into EDF in MDD samples has suggested that those individuals may exhibit anomalies in their ability to intentionally forget negative information, a process that is crucial for emotional regulation and psychological resilience [18, 19]. A study using the item-method directed forgetting paradigm have shown that, compared to healthy controls (HCs), individuals with MDD often struggle with forgetting the negative stimuli that they are instructed to disregard [20]. This impairment is believed to contribute to the rumination and persistent negative bias observed in depression. One study presented that voluntary suppression and conscious retrieval of negative memory may contribute to the difficulties in forgetting negative material in depression with Think/No-Think paradigm [21], moreover, a recent study further proposed that early selective attention may also contribute to the abnormal forgetting in mild depression using directed forgetting paradigm [22].

Although several studies on ERP characteristics of the EDF have been reported, the results were inconsistent because of different experimental paradigms [21] as well as enrollment samples [22]. ERPs are highly valued in cognitive neuroscience due to their excellent temporal resolution, allowing researchers to pinpoint the timing of specific cognitive processes within the brain. ERP studies contribute significantly to our understanding of the brain mechanisms underlying EDF. As such, the method enhances our understanding of EDF mechanisms in depression and could provide critical insights into the cognitive underpinnings of MDD, thereby leading to improved treatment outcomes [23].

In present study, the participants included MDD patients and HCs, and the measurements of ERPs during an EDF task. The purpose of the present study was to investigate the ERP characteristics of the EDF, and further explore the neural mechanism of the cognitive processing of the abnormal EDF in MDD.

Participants included MDD patients (MDD group) and healthy controls (HC group). Inclusion criteria for the MDD group were as follows: (a) met the criteria of MDD of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5); (b) age ranged from 18 to 65 years old; (c) had a minimum primary-school-level education; (d) had normal or corrected-to-normal vision. Exclusion criteria included: (a) met DSM-5 criteria for any other mental disorders; (b) had electroconvulsive therapy or modified electroconvulsive therapy within 6 months before recruitment; (c) had taken medication that damaged cognitive function, such as atropine, or benzodiazepine, during the last two weeks prior to recruitment; (d) had any significant physical or neurological illnesses; and (e) had difficulty fulfilling the experimental requirements. Inclusion criteria for the HC group included: (a) age ranged from 18 to 65 years; (b) a minimum primary-school-level education; (c) well understood the experimental instructions and had capacity to complete the entire experiment.

MDD patients were selected from the Department of Psychology of the Wuxi Mental

Health Center, affiliated with Nanjing Medical University, China. HCs were

recruited from Wuxi City, China, via advertisements in local residential

communities. Sample-size estimation was performed using G*Power software (latest

ver. 3.1.9.7, Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf,

Germany), targeting a statistical power of 0.95 (1-

The present study was conducted at the Wuxi Mental Health Center, affiliated with Nanjing Medical University, China, from December 4, 2020 to July 31, 2023. The research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Wuxi Mental Health Center, affiliated with Nanjing Medical University (WXMHCIRB2020LLkY001), and the study was carried out strictly in accordance with guidelines outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants were told about the equipment used in the experiment and their tasks and they all signed informed consent forms prior to their participation.

In the present study, we used 240 emotional pictures (120 negative and 120

neutral) selected from the Chinese Affective Picture System (CAPS) [24]. These

materials were divided equally into two sets, each containing 120 images (60

negative and 60 neutral). One of the sets served as the study items, and the

other served as the distractors in the recognition test. Both the study items and

distractors were matched in terms of valence and arousal. All affective pictures

used in this experiment were resized to the identical size and resolution (15.5

cm

The experiment consisted of two parts: study phase (see Fig. 1A) and recognition test (see Fig. 1B). A calculation task was performed between the two phases. Subjects were seated in a moderately lit and sound-attenuated room at approximately 60 cm from a computer screen. They were instructed to keep their eyes fixed on the monitor and avoid blinking their eyes or moving their body as much as possible. Before the formal trial, there was a practice session to ensure that all participants were familiar with the procedure.

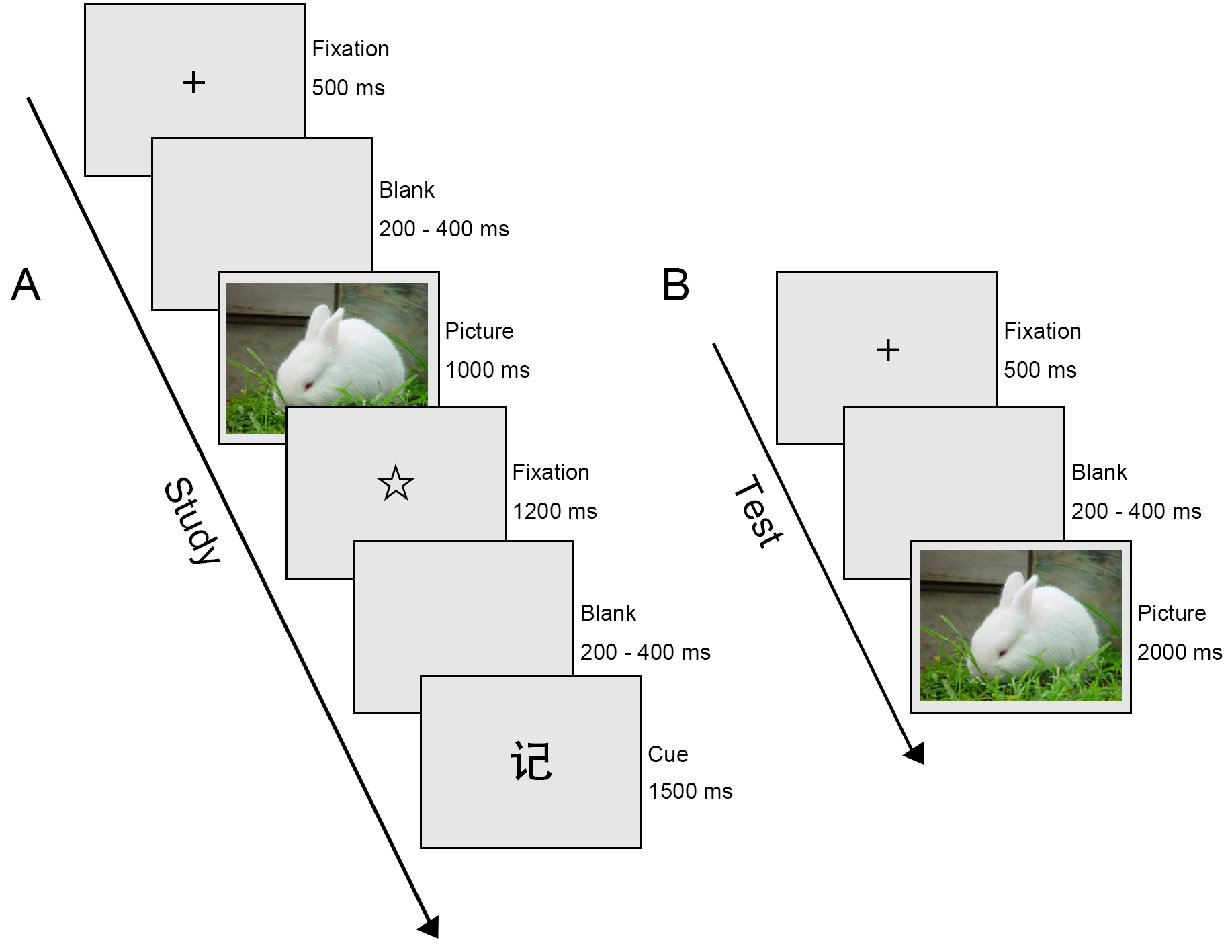

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration of the Emotional Directed Forgetting task. (A) Study phase. ‘记’ cue (Chinese character denoting Remember. (B) Test phase.

During the study phase, 60 negative images and 60 neutral images were presented in pseudo-randomised order for each participant. Initiated by a 500-ms presentation of a black cross in the centre of the screen, a blank screen was displayed with a duration ranging randomly from 200 to 400 ms. After the blank screen, an emotional image was presented for 1000 ms. Subsequently, a second fixation point, a star, was shown for 1200 ms, followed by another blank screen with a duration that varied from 200 to 400 ms, randomly. This was followed for 1500 ms by either a ‘忘’ cue (Chinese character denoting Forget) which meant forget the previous image, or a ‘记’ cue (Chinese character denoting Remember) which meant remember the previous image. The next trial began immediately afterward. It is worth noting that the same instruction was set not to occur three or more times in a row.

After the study phase, participants were instructed to do a calculation test (multiplication of 2- or 3-digit numbers) as a distractor for 5 min.

During the test phase, both the images presented in the first part (60 negative and 60 neutral) and newly presented images (60 negative and 60 neutral) were displayed in pseudo-random order. Each trial began with a blank screen presented for 200–400 ms randomly, followed by presentation of a fixation point, a black cross, lasting for 500 ms. Then an emotional image was displayed for 2000 ms. During the presentation of the image, participants had to decide whether they had seen the picture in the study phase, regardless of the preceding F/R instruction. Subjects were required to click the left or right mouse button with their right index finger to indicate their decisions. The left mouse button was clicked for an image that they had seen before; the right mouse button was clicked for an image that they had not seen before. The assignment of right and left buttons was balanced for all participants.

During the Emotional Directed Forgetting (EDF) task, continuous EEG data were synchronously

recorded using a 64-channel EasyCap (Brain Products GmbH, Wörthsee, Bavaria, Germany) and a BrainAmp

Standard amplifier (Brain Products GmbH, Wörthsee, Bavaria, Germany). The EEG data were continuously

sampled at a rate of 500 Hz and amplified using a 0.1–100-Hz band-pass for

offline analysis. The reference electrode was placed in the centre of the

forehead and the ground electrode was placed 1–2 cm below the left clavicle. For

recording the artifacts produced by blinks and other types of eye movements, two

horizontal electrogram electrodes were placed about 1 cm out from the lateral

canthus of both the right and left eyes, and one vertical electrogram electrode

was placed approximately 1 cm below the centre of the lower margin of the left

eye. Electrode impedance was carefully kept below 5 k

After recording, the EEG data were pre-processed using EEGLAB 2021 toolkit under

the MATLAB 2020b (The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA) environment

platform. The recorded EEG data were filtered by a band-pass of 0.1–30 Hz and

re-referenced to the algebraic average of the two mastoids. The atypical

artifacts from eye movement, muscle, or cardiac components were rejected and

corrected using independent component analysis. Trials contaminated with

excessive artifacts exceeding an amplitude of

For the study phase, two types of trials were left: trials related to emotional images (Neutral or Negative); and trials related to instructive cues (Remember Negative, Remember Neutral, Forget Negative, Forget Neutral).

In accordance with the grand average waveform and previous research [25, 26, 27], image-evoked ERP was selected from four locations along the midline: frontal (FZ), frontocentral (FCZ), central (CZ), and parietal (PZ), for statistical analysis. The average amplitudes of P2 and N2 were calculated after onset of the emotional images within the window of 150–200 ms and 250–300 ms, and the average amplitudes of LPPs were calculated after onset of the emotional images within the window of 500–1000 ms after the onset of image presentation, respectively.

In line with previous study, which analyzed the neural mechanisms underlying directed forgetting in individuals with depressive tendencies [22], we sorted the ERP data into four experimental conditions corresponding to the cues: Remember Negative, Remember Neutral, Forget Negative, and Forget Neutral, to explore the brain activity elicited by the instructions. These conditions were determined by a combination of instructions and valences. The average amplitudes of occipital P1, frontal N2 and parietal P3 components of cue-evoked ERP were analyzed. In particular, the P1 amplitude was calculated as the average amplitude over a window of 80–120 ms after the onset of cues at the electrode sites of O1 and O2. The N2 amplitude was calculated as the average amplitude over a window of 200–250 ms after the onset of cues at the electrode sites of FC1, FC2 and FCZ. The P3 amplitude was calculated as the average amplitude over a window of 300–400 ms after the onset of cues at the electrode sites of CP1, CP2 and CPZ.

The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) (24-item edition), developed by Hamilton in 1960, is the most widely used scale in the clinical assessment of depression. The total scores are less than 20 points is normal, total scores are more than 20 points must be depression, and total scores are more than 35 points is suffering from severe depression [28].

All data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 22 (IBM Corp., Armonk,

NY, USA). Quantitative data and qualitative data comparing the MDD group and the

HC group used the independent t test (two-tailed) and Pearson chi-square

test respectively. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed on both behavioral

data and ERP data. The Greenhouse-Geiser corrected method was used to adjust

statistical results, if necessary. The Bonferroni technique was used to correct

for pairwise comparisons of interactions. A two-tailed Pearson r correlation was

performed between HAM-D24 scores and behavioral/ERP data. Effect sizes were

reported as partial eta squared (

For behavioral data, hit rate, false alarm rate, and reaction times (RTs) were

analyzed. Hit rate was defined as the proportion of old items (images presented

in the study phase) correctly recognised as ‘old’, regardless of type of

instructions. False alarm rate was defined as the proportion of new items (images

never presented in the study phase) incorrectly recognised as ‘old’, regardless

of type of instructions. RT was defined as the time spent from the onset of the

image to the pressing of the mouse button for a correct response. A three-way

mixed, repeated-measures ANOVA was performed for hit rate and RT, with group (HC

vs. MDD) as a between-subjects factor and valence (Negative vs. Neutral) and

instruction (Remember vs. Forget) as within-subjects factors. Considering that

false alarm rate could not be distinguished by instruction, it was analyzed using

a 2

For ERP data, image-evoked P2, N2, and LPP were analyzed using a 2

As shown in Table 1, there was no significant difference between the MDD group and HC group in terms of gender, age, years of education, or handedness.

| Variable | MDD (n = 26) | HC (n = 28) | ||||

| Characteristics | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | t/χ2 | p |

| Age (years) | 41.15 | 10.05 | 38.93 | 6.738 | 0.948 | 0.348 |

| Gender (females/males) | 17/9 | 14/14 | 1.305 | 0.253 | ||

| Education (years) | 12 | 3.6 | 13.36 | 2.934 | 1.523 | 0.134 |

| Handedness (left/middle/right) | 6/6/14 | 5/8/15 | 0.337 | 0.845 | ||

| Age at onset (years) | 34.39 | 10.69 | ||||

| Duration of illness (years) | 6.22 | 6.12 | ||||

| HAMD | 20.79 | 7.33 | 1.91 | 1.88 | 13.11 | 0.000 |

SD, standard deviation; MDD, major depressive disorder; HC, healthy control; HAMD, Hamilton Depression Scale.

Hit rate. The interaction between valence and instruction was significant (F (1,

52) = 10.839, p = 0.002,

| MDD (n = 26) | HC (n = 28) | |||||||

| Remember Negative | Remember Neutral | Forget Negative | Forget Neutral | Remember Negative | Remember Neutral | Forget Negative | Forget Neutral | |

| Hit rate | 0.75 (0.18) | 0.71 (0.18) | 0.64 (0.20) | 0.68 (0.22) | 0.83 (0.11) | 0.81 (0.14) | 0.72 (0.12) | 0.75 (0.14) |

| False alarm rate | 0.28 (0.18) | 0.17 (0.14) | 0.17 (0.14) | 0.12 (0.09) | ||||

| RTs | 885.50 (166.91) | 843.24 (155.86) | 924.11 (144.50) | 888.66 (139.99) | 812.48 (82.22) | 784.57 (102.72) | 851.98 (97.79) | 814.39 (97.72) |

SD, standard deviation; RT, reaction time.

False Alarm Rate. The main effect of group was significant (F (1, 52) = 4.965,

p = 0.03,

RTs. The main effect of group was significant (F (1, 52) = 4.556, p =

0.038,

To ensure the quality of data, we rejected bad epochs caused by inevitable artifacts (e.g., violent muscle shocks, unavoidable signal interference and poorly conditioned electrodes) that the tool for pre-processing could not remove. Consequently, the number of trials in each condition was disparate. The number of trials [mean (SD)] entered into the statistics in the ‘Neutral’ and ‘Negative’ conditions were 52.31 (8.78) and 52.00 (8.88) for the MDD group, and 51.93 (9.70) and 52.86 (8.03) for the HC group, respectively. Moreover, the number of trials under the ‘Remember Negative’, ‘Remember Neutral’, ‘Forget Negative’, ‘Forget Neutral’ conditions were 24.50 (5.98), 24.81 (6.51), 24.69 (6.57), and 25.23 (6.30) for the MDD group, and 26.04 (4.94), 25.82 (5.70), 26.64 (3.86), and 25.43 (5.12) for the HC group, respectively.

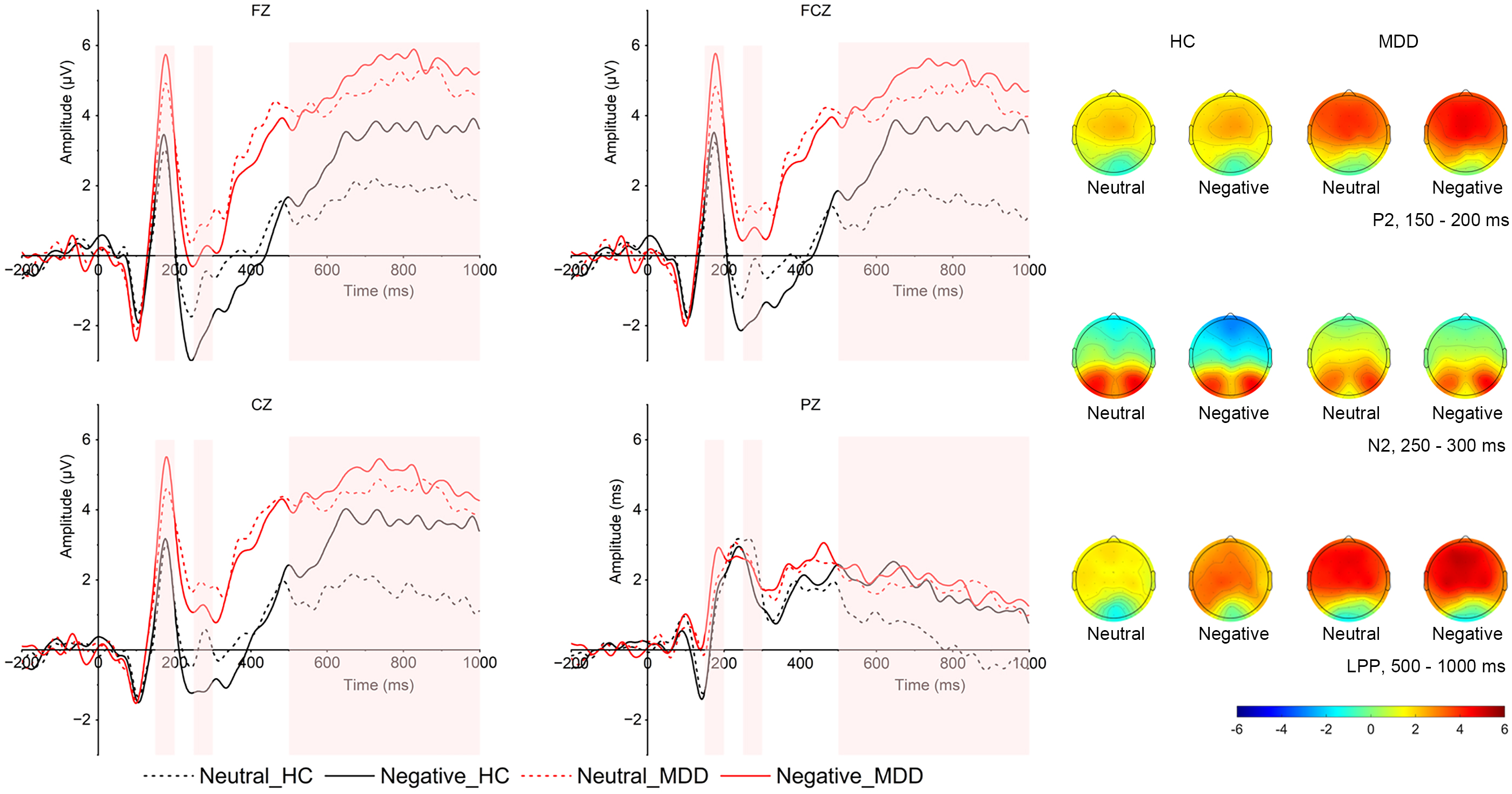

Image-evoked P2. As shown in Fig. 2, in the P2 time window, the main effect of

valence was significant (F (1, 52) = 4.64, p = 0.039,

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Grand averaged ERPs in frontal (FZ), frontocentral (FCZ), central (CZ), and parietal (PZ) locations and topographical distribution of grand averaged image-evoked P2, N2 and LPP of both MDD and HC groups. The image-evoked P2 time window is 150–200 ms; the image-evoked N2 time window is 250–300 ms, the image-evoked LPP time window is 500–1000 ms. LPP, late positive potential; MDD group, major depressive disorder group; HC, healthy control group; ERP, event-related potentials.

Image-evoked N2. The interaction between group and region was significant (F (3,

50) = 4.098, p = 0.011,

For N2 latencies, the interaction between valence and region was significant (F

(3, 50) = 3.075, p = 0.036,

Image-evoked LPP. As presented in Fig. 2, in the LPP time window, there

was a significant interaction between emotion and group (F (1, 54) = 8.120,

p = 0.006,

Cue-evoked P1. There was no other interaction or main effect found with P1 amplitudes or latencies.

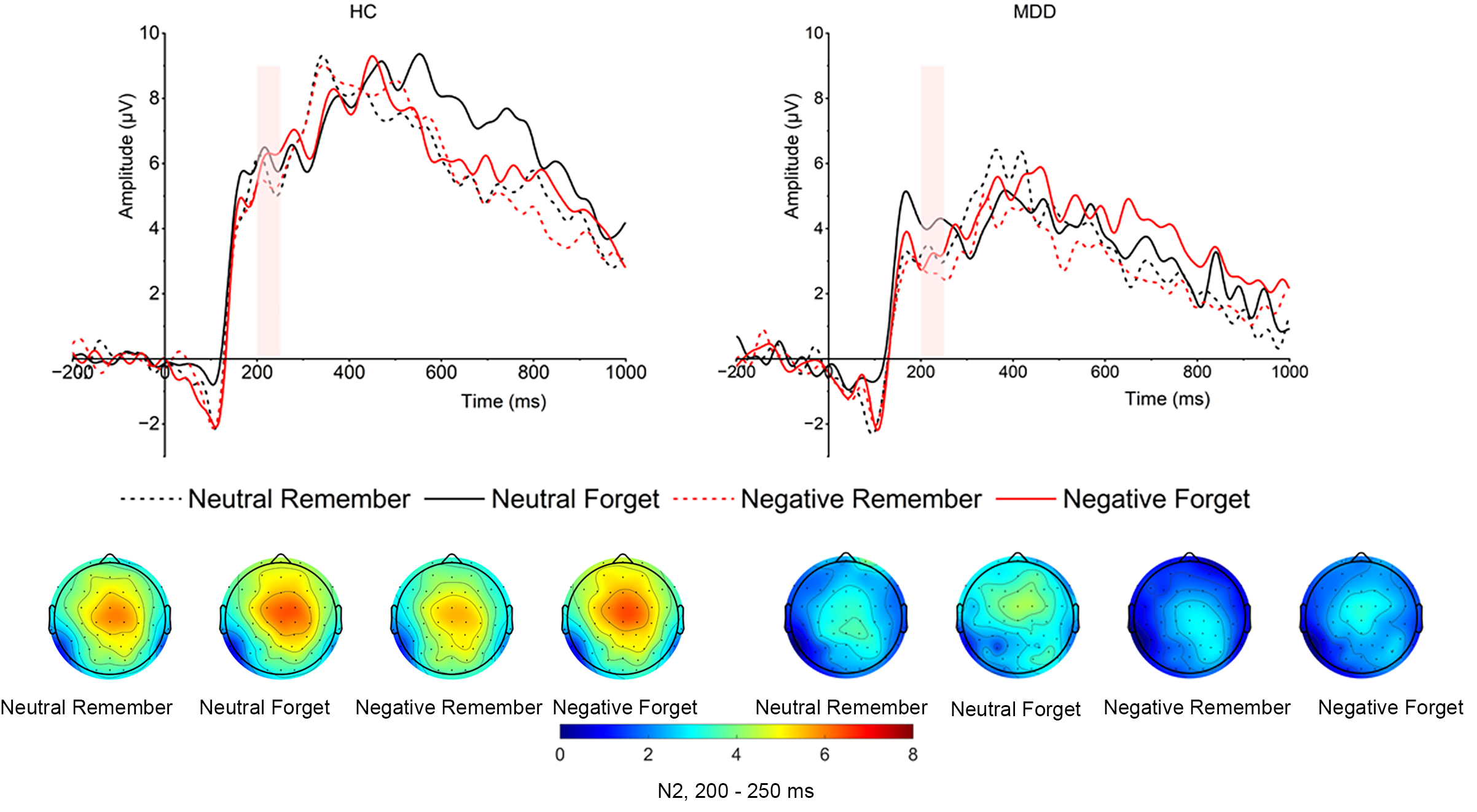

Cue-evoked N2. As shown in Fig. 3, the main effect of group was significant (F

(1, 52) = 6.605, p = 0.013,

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Grand averaged amplitudes and topographical distribution of cue-evoked N2 of both MDD and HC groups. The cue-evoked N2 time window is 200–250 ms.

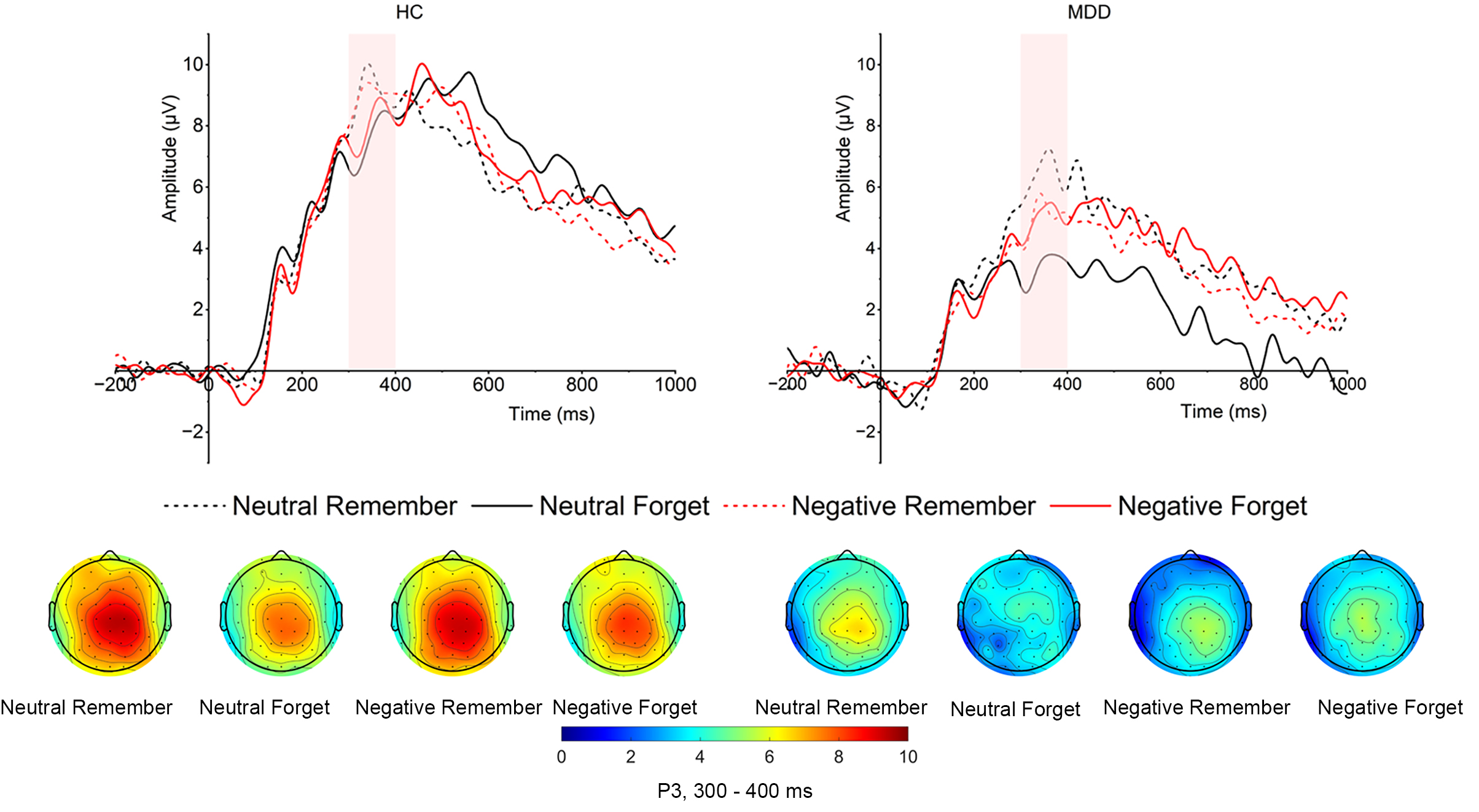

Cue-evoked P3. As shown in Fig. 4, the main effect of

group was significant (F (1, 52) = 8.972, p = 0.004,

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Grand averaged amplitudes and topographical distribution of cue-evoked P3 of both MDD and HC groups. The cue-evoked P3 time window is 300–400 ms.

As shown in Fig. 5, the HAM-D24 scores showed a moderately robust positive

correlation with the LPP amplitudes that were evoked by negative images at the

central location (r = 0.447, p = 0.022). However, the HAM-D24

scores had no correlation with the other ERP components (all p

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Scatterplot of image-evoked LPP amplitudes under negative condition in central location and the HAM-D 24 scores in MDD group. MDD, major depressive disorder; HAM-D, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; LPP, late positive potential.

This study was aimed to investigate the ERP characteristics of the EDF, and further explored the neural mechanism of the cognitive processing of the abnormal EDF in MDD.

In our study, behavioral data showed that the HCs performed better in the EDF task with higher hit rates and fewer false alarms than did the MDD patients. We also found that the impact of valence was significant with higher false alarm rates for negative images in both groups, and RTs were longer for the MDD patients than that for the HCs.

Importantly, the ERP data revealed a larger image-evoked P2 and larger image-evoked LPP for MDD patients, although they had a smaller image-evoked N2 both in negative and neutral emotional conditions than did the HCs. Additionally, MDD patients had larger cue-evoked N2 amplitudes and smaller cue-evoked P3 amplitudes elicited by Remember, than did the HCs.

EDF has been confirmed to represent a cognitive mechanism by which individuals selectively encode and retain or discard emotional information typically guided by directives to Remember or Forget [29]. This process elucidates the interplay between emotional valence and cognitive control systems in modulating memory storage based on its perceived relevance or potential threat. MDD is characterized by negative cognitive biases, which are facilitated by abnormal emotion processing and attenuated top-down cognitive control [30]. Studies have indicated that MDD is associated with distinct patterns of EDF, particularly demonstrating that MDDs have a poorer ability to forget negative emotional material than do HCs [31, 32]. Consistent with the previous studies, our research indicated that it is difficult for MDD patients to forget negative emotional information, i.e., the interactive contribution of emotion and cognition process to the cognitive biases leads to impaired memory facilitation and impaired suppression of negative material. This impairment suggests an enhanced memory bias for negative information, which could exacerbate depressive symptoms by maintaining attention on distressing memories.

ERPs are neurophysiological measures of electrical brain responses that are time-locked to specific cognitive events and provide a detailed temporal resolution of processing dynamics during EDF tasks [33]. The ERP components most frequently examined in EDF studies include the image-evoked (N2, LPP) and cue-evoked (P2, N2, P3) components, each reflecting different cognitive processing stages [27, 34, 35]. The ERP data showed that the image-evoked P2 for MDD patients was larger than that of the HCs. According to previous studies, the P2 component reflects perception and attention to information in the early stages of information processing [36, 37]. However, a previous review indicated that P2 was highly sensitive to bottom-up attentional processing for affective stimuli generally [38]. The task sensitivity may be responsible for the fact that the MDD patients showed larger P2 under differential emotion conditions. Furthermore, in line with a recent study, the larger P2 amplitude in MDD group may suggest excessive allocation of cognitive resources to the matching procedure in memory updating [39]. This kind of attention bias towards self-referential information for patients with MDD may cause worse performance on the task of recalling content. The LPP reflects sustained attentional allocation toward emotionally powerful stimuli [40]. LPP amplitudes are larger for ‘Forget’ instructions applied to negative emotional stimuli than they are for neutral stimuli [35]. Our study showed that MDD patients had larger LPP amplitudes both in negative and neutral emotional conditions, highlighting the difficulty in disengaging from emotionally negative memories. Additionally, we found that the negative images elicited larger LPP than that of neutral images, and this result was consistent with previous studies [27, 41]. The finding suggested automatic attentional allocation to the encoding of the negative stimuli was enhanced. As a result of this prioritization, memory for negative stimuli was suppressed [42]. However, the behavioral data that displayed the higher false alarm rates for negative images suggested that the enhanced LPP elicited by negative images and the lower false alarm rates may not be directly associated. The N2 component is linked to conflict detection and cognitive control. The observed N2 component, reduced image-evoked N2 amplitudes, revealed a memory inhibitory deficit in MDD patients. Moreover, it tends to show larger amplitudes in response to items designated as ‘Forget’—particularly those with negative emotional content [34]. However, beyond the previous study reported that individuals had larger N2 amplitudes on the Forget cues, in the current study, individuals had smaller N2 amplitudes elicited by the Forget cues, suggesting the Forget cues may not in fact be contributing to forgetting in the EDF task [43]. In other words, in the absence of a specific forgetting strategy, the brain may not be effective in allocating cognitive resources and promoting forgetting under the Forget cues. The ERP data also revealed that the N2 amplitudes were larger with the negative images than with the neutral images. The result was in line with previous directed forgetting studies and revealed that individuals tend to mobilize more inhibitory resources to suppress negative memory [21, 27]. The ERP results showed that the HCs had larger P3 amplitudes with the Remember cues than that of MDD patients. The P3 component is associated with attentional allocation and memory updating processes. Moreover, evidence suggests that the amplitudes of P3 are associated with difficulty of the given task [44]. An ERP study on HCs with directed forgetting task revealed that P3 amplitudes are generally higher for emotionally salient stimuli that participants are instructed to remember than are those for neutral stimuli [27]. In the present study, when given the Remember cues, individuals paid attention to the instructions and performed more elaborate coding. MDD patients had smaller P3 amplitudes than that of HCs, indicating difficulties in processing of emotional information in memory retention.

Additionally, our behavioral results revealed that individuals were more likely to misrecognize new negative items as old regardless of types of instructions, suggesting that valence had a significant effect on memory retention. A previous study on healthy individuals with Think/No-Think task found a decreased recall for negative stimuli, compared with neutral stimuli, in the no-think condition, and proposed a possible mechanism that cognitive control could enhance or reduce information in the course of training [45].

There are two limitations that need to be noted. First, the conclusions drawn should be regarded as preliminary owing to the modest sample size used. Subsequent studies would gain from incorporating larger sample sizes and adhering to consistent parameters for analyzing results, in order to bolster the robustness of the findings. Second, the constrained spatial resolution of ERPs utilised in this study underscores the necessity for complementary investigations employing additional neuroimaging techniques. Such methods would facilitate a more accurate delineation of the neural mechanisms underpinning the observed deficits in EDF among MDD patients.

In summary, the present study compared behavioral performance and electrophysiological characteristics of EDF task between MDD patients and HCs. The MDD patients displayed enhanced image-evoked P2 and image-evoked LPP, indicating poor attentional recruiting and allocation. Otherwise, the reduced image-evoked N2 amplitudes in MDD patients, indicating memory inhibitory deficit, as well as the reduced cue-evoked P3 amplitudes, indicating difficulties in memory retention. The overall findings offered evidence for the poor performance in the EDF task in MDD patients, provided valuable insights into the neural mechanisms underlying the EDF task, and highlighted the differences between HCs and MDD patients. Otherwise, the reduced P3 amplitudes elicited by the Remember cues in MDD patient were observed. Our findings further extended prior EDF studies that used only behavioral measurements and provided additional empirical evidence and may contribute to the understanding of the mechanisms that underlie the onset and maintenance of MDD. These findings underscore the potential of EDF as an assessment tool for cognitive and emotional dysregulation in MDD. This line of inquiry not only deepens our understanding of the cognitive aspects of depression but also holds promise for enhancing therapeutic strategies, e.g., defining novel therapeutic targets for transcranial magnetic stimulation, to improve memory function and emotional regulation in MDD.

MDD, major depressive disorder; HC, healthy control; ERP, event-related potential; EEG, electroencephalogram; EDF, emotional directed forgetting; RT, reaction time; HAM-D, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale.

The datasets used and analyzed in the present study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

CC and XTZ designed the research study. XTZ and XHL performed the research. XHL, XZG and LMC provided help and advice on the experiments, CC analyzed the data, ZHZ and HLZ guided the experimental design and revised the article. All authors took part in drafting, revising, or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The research program was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Wuxi Mental Health Center, affiliated to Nanjing Medical University (WXMHCIRB2020LLkY001), and the study was carried out strictly in accordance with guidelines outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. All of the participants provided signed informed consent.

We are grateful to all the people (except the authors of this article) who took part in this study.

This study is supported by Wuxi Municipal Health Commission Major Project (No. 202107) and Wuxi Taihu Talent Project (No. WXTTP 2021).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.