1 Department of Neurology, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Dalian Medical University, 116027 Dalian, Liaoning, China

2 College of Basic Medicine, Dalian Medical University, 116044 Dalian, Liaoning, China

3 Department of Anatomy, College of Basic Medicine, Dalian Medical University, 16044 Dalian, Liaoning, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Cerebral small vessel disease is a common disease endangering human health due to its insidious and repeated onset and progressive aggravation. White matter hyperintensities (WMHs) are one of the classic imaging markers of cerebral small vessel disease. The term ‘WMHs’ was first proposed by Hachinski in 1987. The WMHs in our study mainly refer to cerebral white matter damage caused by various vascular factors, known as vascularized white matter hyperintensity. WMHs are significantly correlated with stroke, cognitive dysfunction, emotional disturbance, and gait abnormality, and have drawn widespread attention. This article reviews the research progress on the pathogenesis of cognitive dysfunction associated with WMHs and provides a theoretical reference for understanding the pathogenesis of WMHs and the early assessment of associated cognitive dysfunction.

Keywords

- cerebral small vessel disease

- magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

- quantitative MRI

- cognition

- cognition disorders

White matter hyperintensities (WMHs) are commonly seen in older adults. In those aged 60–70 years, 87% had subcortical WMHs and 68% had periventricular WMHs; in those aged 80–90 years, 100% had subcortical WMHs and 95% had periventricular WMHs. WMHs are significantly correlated with stroke, cognitive dysfunction, emotional disturbance, and gait abnormality, and had attracted widespread attention [1, 2]. Many studies had explored the relationship between WMHs and cognitive impairment, with WMHs especially related with impairment in executive function, attention, and processing speed [3, 4, 5, 6, 7]. Severe WMHs burden is an independent predictor of dementia and cognitive decline [4]. Although most elderly people over 60 years old develop WMHs [5], not all WMHs develop cognitive impairment, and patients with a similar visual extent of WMHs may show different degrees of cognitive dysfunction, affecting different cognitive domains [6]. Sign of cerebral small vessel disease on conventional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) includes WMHs, in recent subcortical lacunar infarcts (clinically symptomatic), lacunes (clinically silent), cerebral microbleeds, prominent perivascular spaces and cerebral atrophy [7].

In other words, the relationship between WMH load and cognitive impairment may not be straightforward, and the underlying mechanism remains unclear. This article reviews the research on the correlation between WMHs and cognitive impairment. The purpose of this review is to improve clinicians’ understanding of the relationship between WMHs and cognitive dysfunction, as well as to provide theoretical reference for the discovery of the pathogenesis of WMHs and the early assessment of the associated cognitive dysfunction.

A literature search was conducted to test and prove the claims. PubMed databases were used to find studies for the inclusion in the systematic review. The database was searched using the following keywords: Cerebral small vessel disease, Cognition, cognitive impairment, WMHs. Publication years were 2018–2023. The total number of articles retrieved by using PubMed was 414. Among these articles, 364 were excluded for the following reasons: (1) subjects were not individuals aged 60 to 90; (2) there were no specific mention of cognitive impairment related to the destruction of the structural integrity of white matter fiber bundles in WMHs; (3) no specific mention of the severity of WMHs and Cerebral Blood Flow (CBF) in normal elderly thus flow was negatively correlated. For these reasons, 50 potentially relevant studies were obtained for the systematic review.

The subjects were individuals aged from 60–90, and there was specific mention of cognitive impairment which was related to the destruction of the structural integrity of white matter fiber bundles in WMHs, and the severity of WMHs and CBF in normal elderly flow were negatively correlated.

Search terms used were for cerebral small vessel disease (CSVD): “cerebral small vessel disease”, “Cerebral Small Vessel Diseases” [Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)], “small vessel disease”, and microangiopathy. MRI: “quantitative MRI”, Dynamic contrast enhanced MRI: “dynamic contrast enhanced” and “MRI”. Cognition: “Cognition disorders” [MeSH] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The process of selecting articles. WMHs, White matter hyperintensities; CBF, Cerebral Blood Flow. The figure was drawn by Review Manager 5.4 (The Cochrane Collaboration, Manchester, UK).

Through diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) study, it has been established that cognitive impairment was related to the destruction of the structural integrity of white matter fiber bundles in WMHs, and white matter damage in different parts of the brain can lead to cognitive impairment in different domain [7]. There was a general loss of microstructural integrity in the severe WMH group, while there was no significant difference between the mild WMH group and the no WMH group. There was a region-specific link between alterations in white matter microstructure and cognitive function [8]. Disruption of the white matter fiber tracts may cause disconnections between cortical-cortical or subcortical pathways which was critical for some cognitive functions, and the so-called “disconnection hypothesis” may play a role for in WMHs-related cognitive impairment [9, 10]. In 2011, Maillard et al. [11] scholars imaged fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) and DTI in 208 patients and found that there were no definite boundaries, but an overlap between normal brain tissues. Therefore, the white matter hyperintensity penumbra concept of a WMHs penumbra was proposed [11]. WMH penumbra (WMHs-P) represents a lighter injured area around WMH lesions, with a higher probability of progression to WMHs compared to normal white matter outside the penumbra. To explore the relationship between the progressive impairment of the microstructure of WMHs white matter fiber bundles and cognitive decline, Qiu et al. [12] explored the DTI changes in WMHs and WMHs-P in the corpus callosum using the DTI technique; they found that the abnormality of WMHs-P microstructure played an important role in cognitive decline. Changes in the DTI index of WMHs-P always preceded the development of WMHs and were associated with cognitive impairment, possibly due to reduced endothelial damage and blood-brain barrier (BBB) generality in due to demyelination and axonal damage [13]. Another study of cognitive impairment in older adults found that effects of microstructural changes caused by WMHs may spread beyond WMHs-P regardless of the effects of total WMHs load and that disruption of the microstructural integrity of distal white matter tracts other than WMHs-P may also led to impairment of attention and executive function [14]. It also suggested that the integrity of the distal white matter fiber bundle may play an important role in cognitive function. Thus, changes in DTI detection measures in white matter microstructures may be an underlying mechanism of WMHs-related cognitive impairment. WMHs-P is considered a more diffuse and early brain injury and may represent a novel therapeutic target that, if successful, may alter the time course of WMHs and its cognitive consequences.

Resting-state MRI (rs-fMRI) technology identifies a series of resting-state networks (RSNs) based on blood oxygen level-dependent signals (BOLD), where the default mode network (DMN) is considered to be cognition-related [15, 16]. Loss of the integrity of brain white matter structures affects functional network connectivity, and this disruption of the network anatomy leads to cognitive impairment [17]. The accumulation of WMHs load was found to be associated with alterations in both functional and structural connections within the DMN. In the stage of severe WMHs load, network function was significantly impaired, with subjects’ enhanced DMN functional connectivity in the medial frontal gyrus; and increased disruption of the white matter tract microstructure between the hippocampus and the posterior cingulate gyrus was an independent indicator of memory loss [18]. Furthermore, reduced functional connectivity of the DMN in the thalamus and increased disruption of the white matter tract microstructure between the thalamus and the posterior cingulate gyrus were independent risk factors for slower processing speed. Cognitive impairment in older WMHs patients was not only implicated in the integrity of white matter tracts connecting functional modules in the DMN [18], but also in functional connectivity in the DMN, with weaker connectivity between WMHs patients and other rest-state brain networks [19].

Study has demonstrated that the severity of WMHs and CBF in healthy elderly individuals were negatively correlated, indicating an increase in baseline cerebral blood flow could reduce the incidence of WMHs [20]. Patients with mild cognitive Impairment (MCI) had regional cerebral perfusion such as cortical hypothalamus and caudate nucleus, and memory decline was associated with hippocampus and posterior cingulate gyrus and increased cerebral perfusion [21, 22]. In a related study, in an application of 3D pseudo-continuous arterial spin labeling (3D-pCASL) technology to measure cerebral blood flow in elderly Latino WMH subjects, it is found that CBF in the local area of the middle cerebral artery was positively correlated with Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) score in WMH subjects, whereas CBF was negatively correlated with MoCA score. This difference may be related to the different degrees of damage to WMH caused by differences in cerebral perfusion [23]. Cerebral blood flow increased in brain regions susceptible to cerebral perfusion in the early stage [24]. The increase in cerebral blood flow in the early stage of white matter hyperintensity may be related to compensatory cerebral blood flow redistribution. However, with the progress of white matter hyperintensity, cerebral blood flow compensation was insufficient to maintain the balance of global cerebral perfusion [24]. Thus, based on these findings it appears that increased blood flow may be an early indicator for identifying cognitive decline and can be used to assess the risk of cognitive impairment in WMH patients, which was a potential area for further research.

Cerebrovascular Reactivity (CVR) is a crucial indicator of cerebrovascular functional reserve and reflects the body’s self-regulation to cerebral blood flow in response to the internal and external environment. In WMHs patients with CVR impairments, a weaker CVR correlates with increased severity of cognitive impairment [25, 26]. Ni et al. [27] applied the BOLD signal detection method to study the pathogenesis of CVR in the development of WMH-related cognitive impairment. Their findings suggest that CVR was impaired in patients with moderate-to-severe WMH, with greater reductions in frontal lobe regions from the non-cognitively impaired group to the cognitively impaired group [27]. Hemodynamic disturbances can lead to the appearance of areas of reduced CVR followed by WMH areas, and damage to white matter fiber tracts further reduces functional connectivity between brain regions. Studies had found that changes in brain network functional connectivity and CVR in WMH subjects were related to cognitive decline [28, 29]. In sum, severe WMH may lead to decreased CVR, which then induces abnormal functional connectivity, ultimately leading to cognitive decline. Functional connectivity in the left middle occipital gyrus was positively correlated with general cognition and information processing speed, and highly correlated with periventricular WMH, but not deep WMH. Thus, impaired CVR may be an early marker for identifying cognitive decline and could be used to assess the risk of cognitive impairment in WMH patients.

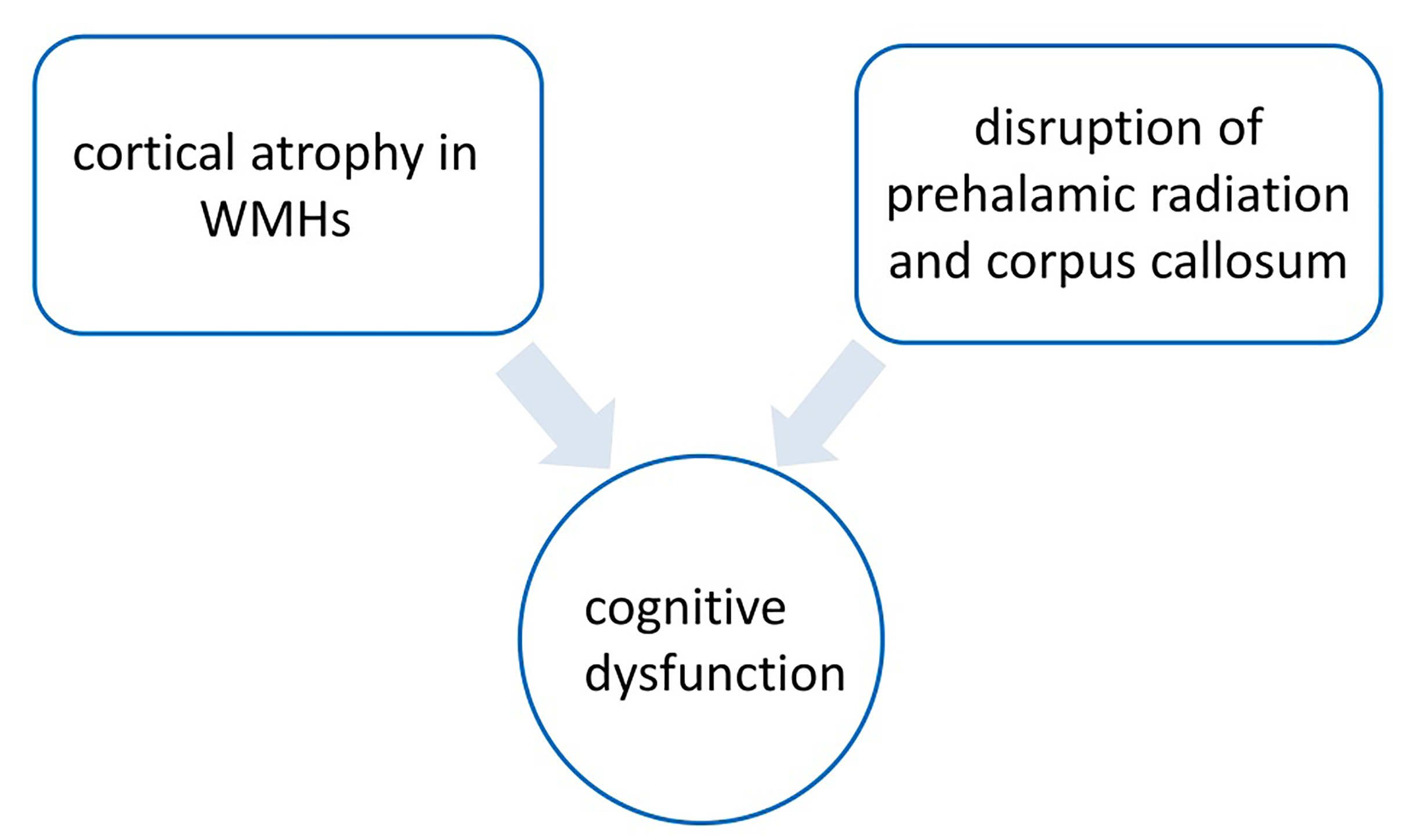

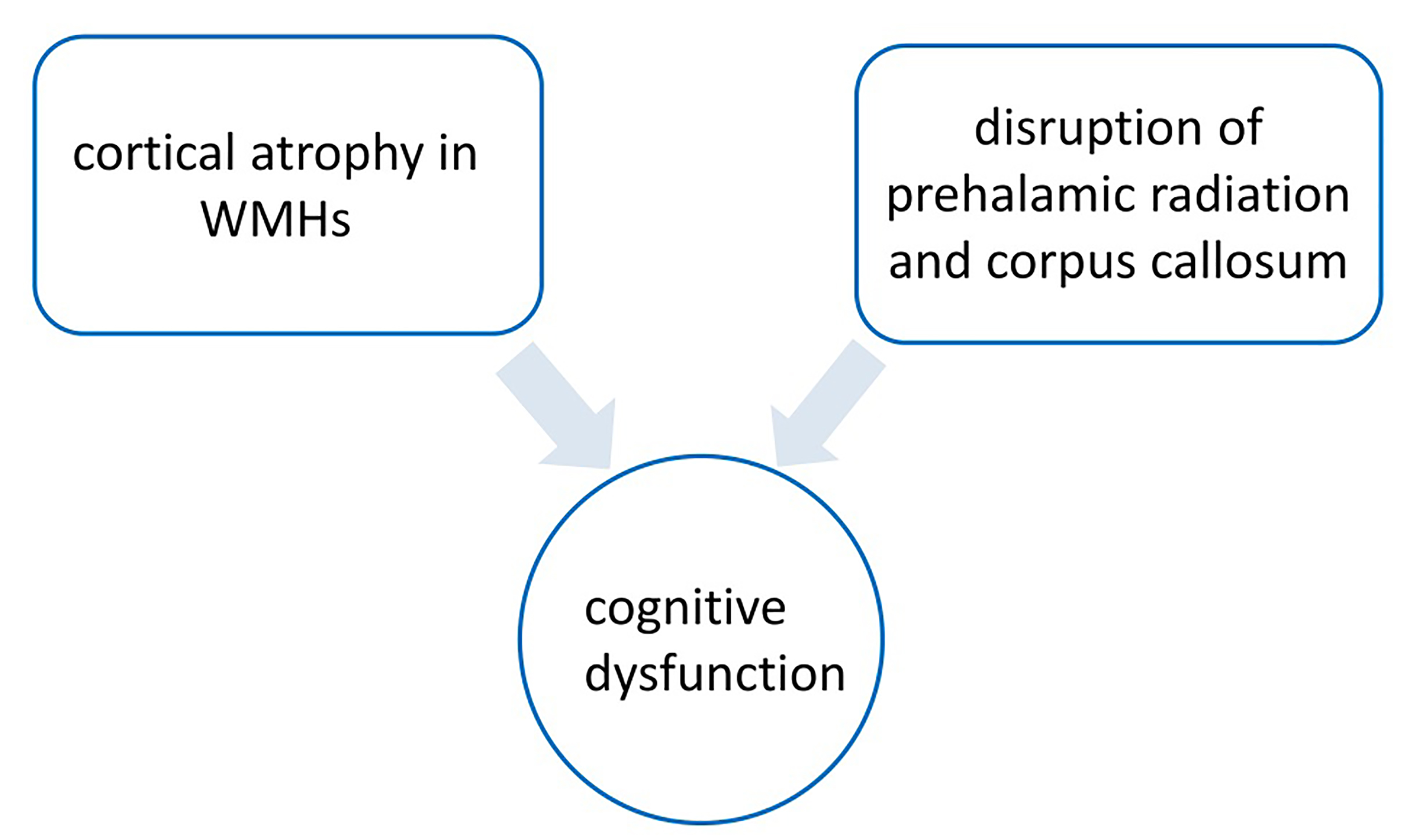

High WMH load had been associated with cortical atrophy in the frontal and temporal lobes [30, 31]. In individuals who were cognitively normal, as well as those with mild cognitive impairment or dementia, the relationship between WMH and global cognition was mediated by global or local gray matter volume [32]. A survey of 521 middle-aged adults with normal cognitive ability found that higher WMH lesion volume was significantly associated with lower gray matter volume in the temporal, frontal, and occipital lobes, as well as in the thalamus and cerebellum. There was a significant correlation between gray matter volume and WMH volume and processing speed in a wide range of brain regions, including the thalamus [33]. Zhu et al. [34] found that grey matter atrophy in the thalamus and frontal insular cortex of patients with mild cognitive impairment with WMH was associated with cognitive decline, which may mediate the relationship between WMH and cognitive function. As described in previous studies, there were two possible mechanisms to explain this finding [34, 35]. First, disruption of cortical and subcortical white matter fiber tracts (i.e., prethalamic radiation and corpus callosum) in WMH patients may lead to structural and functional abnormalities of sub frontal subcortical neural networks, ultimately leading to cognitive dysfunction [36, 37].

Second, another possible mechanism, direct damage, such as cortical microinfarction and microbleeds, may also be responsible for cortical atrophy and subsequent cognitive dysfunction in WMH. A study of hippocampal subregions found that atrophy in the hippocampal subregion was exacerbated with an increase in WMH, especially periventricular WMH load, and atrophy of WMH and gray matter, including the hippocampus, was often a co-existing pattern that jointly promoted the development of cognitive dysfunction [38]. WMH indirectly affected the integrity of gray matter through cortical-subcortical loss, leading to atrophy of the hippocampus; more specifically WMH in the region of fiber bundles connected to the hippocampus may cause axonal loss and subsequent hippocampal atrophy through Wallerian degeneration. The relationship between WMH and hippocampal atrophy also suggests the exacerbating effect of ischemia and hypoxia on brain atrophy, which were basically consistent with previous research results, and there may be a common vascular etiological basis between WMH and gray matter abnormalities [38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43]. Similarly, medial temporal lobe atrophy is thought to be closely associated with cognitive impairment, while periventricular WMH is an independent predictor of medial temporal lobe atrophy, and periventricular WMH affects executive function through its mediation to the medial temporal lobe [44]. Patients with WMH around the occipital ventricle may have gray matter atrophy in the left precentral gyrus and left insula, which may be related to the levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and reduction of apolipoprotein B (Apo-B), but more large-scale studies were needed for further demonstration. In addition to cerebral gray matter, reduced cerebellar gray matter volume was also involved in the impairment of memory, processing speed, and executive function in WMH patients [45]. This process may be related to WMH disrupting the cognitive network connection between the cerebellum and the fronto-parietal lobe. Gray matter atrophy in specific regions of the cerebellum and impaired network functional connectivity are associated with the severity of WMH [46, 47, 48] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Mechanism of white matter hyperintensity (WMH) mild cognitive impairment. The figure was drawn by Review Manager 5.4 (The Cochrane Collaboration, Manchester, UK).

The vascular nerve unit is crucial for maintaining neuronal physiological function and repairing damaged neurons, with the BBB being a key component in this process. The BBB interacts with and regulates other components of the vascular nerve unit to sustain brain function [49]. The BBB prevents cells and molecules from entering the brain tissue and removes the accumulation of metabolic wastes in the brain. Endothelial cells are a core component of the BBB and play an important role in maintaining the homeostasis of the brain [50]. The damage to endothelial cells and the basement membrane of small arteries caused by various factors accelerates endothelial dysfunction, destruction of BBB permeability, ischemia and hypoxia, neuronal necrosis, demyelination, inflammatory response, etc., and eventually leads to WMH and other series of changes [51, 52]. WMH patients have different degrees of cognitive impairment, which may be related to changes in the permeability of the BBB [53]. A study by Young et al. [54] found that endothelial cell function and BBB integrity were significantly reduced in leukoencephalopathy compared with normal brain tissue. Similarly, research found that the permeability of the BBB in elderly patients with ischemic WMH was generally increased with the severity of WMH. The greater the permeability of the BBB is, the more serious the impairment of cognitive function will be. The BBB has also been recognized as an early biomarker of cognitive impairment [55]. Cognitive decline, especially in executive function, in patients with WMH was associated with the extent of BBB leakage at baseline [56]. BBB leakage can lead to local microbleeds and reduced distal blood flow, aggravating cerebral ischemia and hypoxia. In addition, leakage, and deposition of bloodborne substances can lead to perivascular edema, damage brain cells and cause demyelination [57].

Dynamic contrast enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (DCE-MRI) is a reliable method to quantify BBB permeability. Through the BBB leakage rate assessment by DCE-MRI, it is found that subjects with higher WMH burden had significantly higher BBB leakage rate and area under the leakage curve, and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) scores decreased with increasing WMH leakage rate. Higher BBB permeability is associated with higher WMH load and cognitive decline. Impaired BBB integrity may be a key factor in the pathogenesis of WMH and is part of a series of pathological processes that ultimately lead to cognitive impairment [53]. Consequently, DCE-MRI is valuable to evaluate BBB permeability changes following white matter injury and its association with cognitive impairment.

Studies had shown that chronic inflammatory response, oxidative stress, etc., are related to the occurrence of WMH [58]. Ischemia and hypoxia can cause endothelial dysfunction, activation of glial cells, and increased permeability of the BBB, among others, leading to inflammatory reactions. At the same time, inflammatory factors lead to further damage to the vascular endothelium and leakage of cerebrospinal fluid, forming a vicious circle, promoting the occurrence and development of WMH [58, 59].

Inflammation and oxidative stress reduce nerve impulses by affecting the proliferation and differentiation of oligodendrocytes and precursor cells. This results in the release of various growth factors and chemicals, increased vascular permeability, protein exudation, and axonal demyelination, and further reduces the conduction of nerve impulses, which in turn play an important role in the occurrence and development of cognitive impairment [60, 61]. A community-based cohort study examined the relationship between 15 different inflammatory biomarkers and CSVD and confirmed the involvement of inflammatory response in the pathogenesis of CSVD, especially the important role of endothelial-associated inflammatory biomarkers in WMH, while different inflammatory cascades may underlie different subtypes of CSVD [62]. Inflammation is one of the key factors leading to cognitive impairment in WMH patients. Different inflammatory biomarkers were found to be involved in the occurrence and development of WMH, and further mediate the occurrence of cognitive dysfunction. C-reactive protein (CRP) is a sensitive but non-specific indicator of inflammatory factors, involved in local or systemic inflammatory response. High sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) is more sensitive than CRP. Recent studies have shown that CRP is an inflammatory marker of cognitive dysfunction [63, 64]. Studies indicate that cerebral microstructural disintegration, which primarily impacts frontal circuits and related executive function, is linked to low-grade inflammation as measured by high-sensitivity C-reactive protein. An analysis of 219 patients with WMH found that elevated hs-CRP levels were associated with increased WMH and decreased brain parenchymal volume, with higher serum hs-CRP levels associated with greater decline in executive function. High hs-CRP was related to memory and visuospatial impairment. It was shown that hs-CRP can be used as an early sensitive indicator of white matter microstructural integrity [65].

Interlrukin-6 (IL-6) is a pleiotropic cytokine that significantly influences host defense by modulating immune and inflammatory responses. A study involving 1841 elderly patients aged 65 to 80 utilized MRI and fasting serum IL-6 measurements to investigate its correlation with WMHs. The analysis revealed a positive correlation between the level of serum IL-6 and WMH volume [66], suggesting elevated IL-6 levels could lead to increased WMH volume and might be involved in the early pathology of WMH-associated cognitive impairment [67].

Lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 (Lp-PLA2) is a

phospholipase secreted by inflammatory cells. Lp-PLA2 can hydrolyze oxidized

phospholipids in oxidized low-density lipoprotein (ox-LDL) to produce lipid

pro-inflammatory substances [68]. Studies have shown that Lp-PLA2 is not only

involved in the pathophysiological process of atherosclerosis, but elevated

levels of Lp-PLA2 are also associated with ischemic stroke and cognitive

dysfunction [69, 70]. A study in northern Manhattan included a stroke-free

community sample, including Hispanic, black, and white participants, and

quantitatively measured the relationship between WMH volume (WMHV) and levels of

inflammatory biomarkers Lp-PLA2, myeloperoxidase, and hs-CRP [71]. It found that

the relative elevation of Lp-PLA2 and myeloperoxidase was associated with the

exacerbation of WMH, but not hs-CRP. Zhu et al. [72] found that Lp-PLA2

in patients with severe WMHs was significantly lower than in patients with mild

or moderate WMH lesions, and Lp-PLA2 was linearly positively correlated with

cognitive dysfunction in WMH patients, but not associated with LDL-C [72]. There

are also regional differences in the influence of inflammation on WMH. Serum

Lp-PLA2 is related to periventricular WMH (PWMH), but not to deep WMH (DWMH), while PWMH is considered to be

related to executive ability and attention [57, 73]. Matrix metalloproteinases

(MMPs) are a family of zinc- and calcium-dependent endopeptidases mainly secreted

by neurons and glial cells, including MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-9, etc. [74]. They cleave

most extracellular matrix proteins, participate in various physiological

functions, such as tissue remodeling, inflammation, and angiogenesis and

participate in cognitive processes [74, 75, 76, 77]. Studies have shown that in patients

with ischemic stroke, higher MMP-2 plasma levels are associated with increased

WMH volume on MRI, which may reflect capillary remodeling and vascular generated

increase [78, 79]. MMP-2 may increase BBB permeability and leakage, thereby

promoting the progression of WMH. Evidence from animal and human studies suggests

a link between MMP-2 and white matter disease [79]. In a hypoperfusion rat model,

MMP-2 was associated with optic nerve and corpus callosum demyelination, and

MMP-2 expression was increased in microglia and capillary endothelium [80, 81].

Cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) MMP-2 is not only associated with white matter integrity and basal ganglia

volume changes, but also related to motor skills, cognitive flexibility,

abstraction, verbal memory, and visual memory [82]. MMP-9 activity is more active

in the frontoparietal cortex in Alzheimer Disease and mild cognitive impairment

compared to healthy subjects, and increased expression of MMP-9 in the

hippocampus is involved in the development of

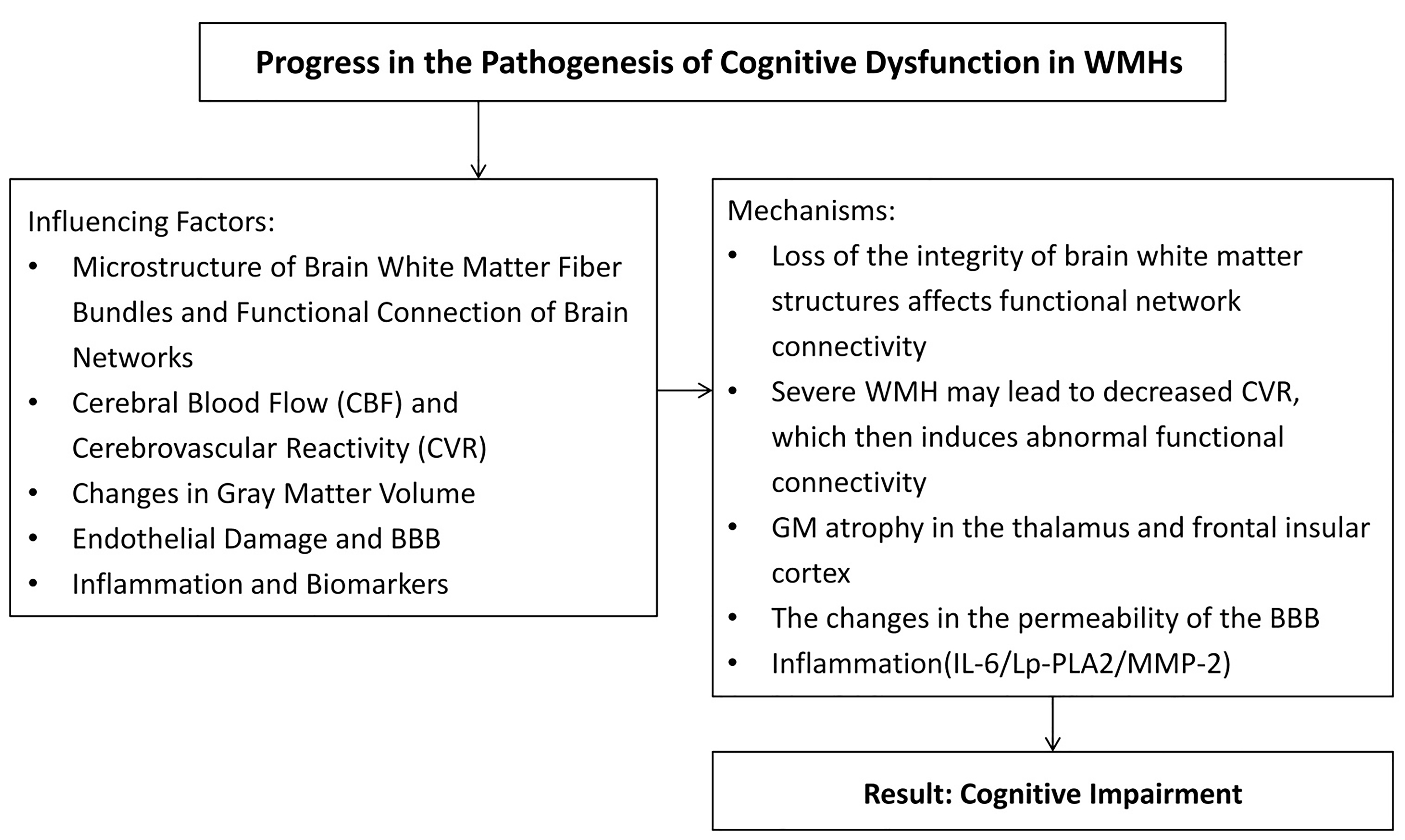

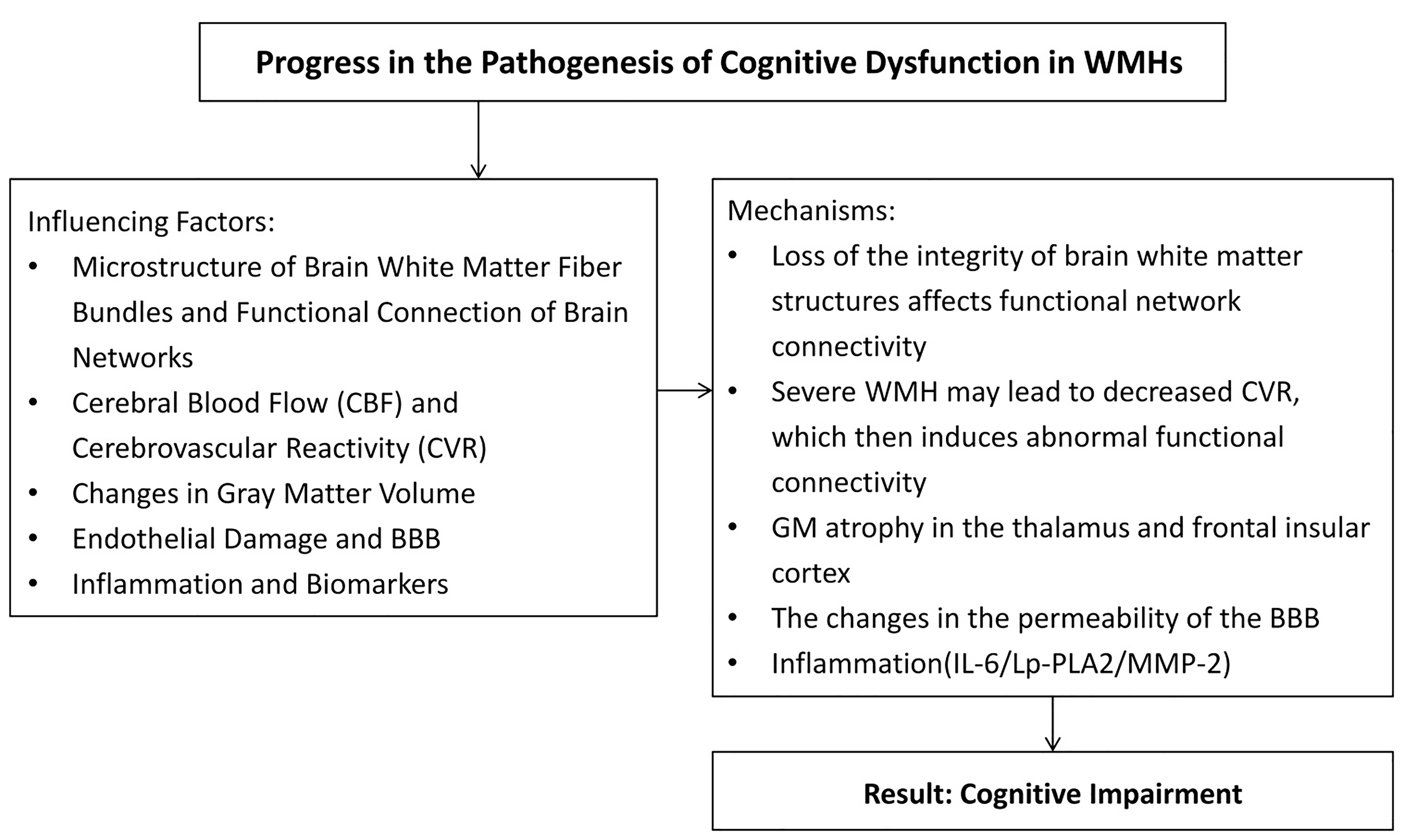

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Summary of influencing factors and mechanisms of injury of cerebral white matter caused by vascular factors. BBB, blood-brain barrier; Lp-PLA2, Lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2; MMP-2, Matrix metalloproteinase-2; IL-6, Interlrukin-6; CVR, Cerebrovascular reactivity; GM, Gray matter. The figure was drawn by Review Manager 5.4 (The Cochrane Collaboration, Manchester, UK).

Other inflammatory markers, including serum homocysteine Hcy, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, and serum amyloid protein, have been identified by related studies. Higher levels of inflammatory markers are associated with greater severity of the WMH and more pronounced cognitive function [85]. Further studies with larger sample sizes are needed to better understand this relationship.

Many studies had divided WMH into PWMH and DWMH according to its site [86]. This classification is highly feasible and reproducible and can be used to score WMHs by using the Fazekas scale [86]. Since PWMH and DWMH have different pathological features and anatomical locations in the brain, they have different effects on cognitive impairment [87]. WMH is a well-established marker for predicting gait dysfunction via disruption of network and cortical thinning. Located in the watershed region and susceptible to chronic hypoperfusion, PWMH has been associated with cerebral ischemia, demyelination of adjacent fiber tracts, and loss of periventricular ependyma [88]. The PWMHs-related cognitive impairment suggests the disruption of the cholinergic projection from the basal ganglia to the cortex, and the increased level of microglia. This may be related to the neuroinflammation response after the disruption of the blood brain barrier (BBB). In contrast, DWMH may begin with atherosclerosis, occlusion of deep penetrating arterioles, and can progress gradually with progressive demyelination of previously injured tissue. DWMH is not adjacent to the ventricle and is a solitary lesion, and the volume of WMH may be related to lipid peroxidation in blood. That is, PWMH is a mostly non-ischemic injury, reflecting more extensive gliosis, and DWMH is associated with ischemic tissue injury [88, 89]. Compared with DWMH, PWMH has a greater correlation with patients’ executive function decline [90, 91]. The possible reason is that PWMH damage interferes with long fibers, leading to poorer performance in most cognitive domains, whereas DWMH damage is the cause of short fibers, which are less relevant to cognitive function, but may play an important role in motor dysfunction [92, 93]. However, parietal-temporal DWMH is more strongly associated with memory loss. The spatial distribution of WHMs may directly affect specific brain networks, resulting in different cognitive impairments [94]. The relationship between the total WMH load (the sum of PWMH and DWMH) and cognitive impairment is still inconclusive. Silbert et al. [95] found that the progress of total WMH volume and PWMH volume was more predictive of cognitive impairment than baseline WMH load. However, different studies present different results, which may be due to differences in research populations and evaluation methods [96].

An additional disease associated with WMH development is weakened BBB. Higher leakage rates and volumes in an MRI investigation showed that the BBB breakdown in the WMH was more severe compared to no-appearing gray matter and white matter. The degradation of the BBB was more severe in areas adjacent to WMHs, consistent with other findings of increased in BBB permeability close to the WMHs [96].

Executive function, attention, and immediate/delayed memory are linked to WMH progression. Lesions known as WMHs are identified by T2-weighted imaging or FLAIR as hyperintense regions. In juxtacortical white matter, deep WMHs are frequently smaller and asymmetrically distributed. This distribution points to localized perfusion deficits brought on by hypertensive artery disease. Symmetrically arranged around the ventricles, periventricular WMHs point to diffuse perfusion problems associated with occlusive periventricular venous collagenosis [97, 98, 99].

There are some limitations in this paper, including the lack of histopathological analysis of WMHs and the need to explore whether WMHs of different origins affect gray matter and cognitive function differently. Further research is needed to analyze pathophysiological differences among lesions by comparing patients with different pathologies, such as multiple sclerosis or vasculitis.

None of the above-mentioned single factors can be considered as the sole cause of cognitive decline. These events are interconnected, and there are cross-effects between different mechanisms, which may produce cascade reactions, leading to cognitive impairment. Future research can explore the etiology and mechanism of WMH-related cognitive impairment from the perspectives of neuropathology, neuroimaging, and neuropsychology, combined with clinical manifestations, genes, and other aspects. The hyperintensity of white matter, also known as vascularized WHMs, indicates damage to the cerebral white matter caused by various vascular factors. Therefore, its use as an intermediate marker in research settings and its detection in clinical diagnostic investigations suggest a higher risk of cerebrovascular disease. To aid in the design of therapy trials that include the progression of WHMs as an intermediate end point, more research is required to evaluate the effects of this end point on dementia and stroke. Blocking these receptors lowers the frequency and amplitude of peristaltic contractions. More research is needed in this area, and we look forward to discovering more mechanisms in the future.

NS: Conceptualization, supervision, and review and editing of the manuscript. JY, CW, XQ-W and GM: Data curation. XY and XG-W: Investigation, writing the original draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC 32100928).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.