1 Department of Anesthesiology, Institution of Neuroscience and Brain Disease, Xiangyang Central Hospital, Affiliated Hospital of Hubei University of Arts and Science, 441000 Xiangyang, Hubei, China

Abstract

Microglia play a crucial role in monitoring the microenvironment of the central nervous system. Over the past decade, the role of microglia in the field of pain has gradually been unraveled. Microglia activation not only releases proinflammatory factors that enhance nociceptive signaling, but also participates in the resolving of pain. Opioids induce microglia activation, which enhances phagocytic activity and release of neurotoxic substances. Conversely, microglia activation reduces opioid efficacy and results in opioid tolerance. The application of microglia research to clinical pain management and drug development is a promising but challenging area. Microglia-targeted therapies may provide new avenues for pain management.

Keywords

- microglia

- pain

- opioid

Microglia are the resident immune cells in the central nervous system (CNS), and they play a critical role in maintaining homeostasis and responding to insults [1, 2]. They are derived from myeloid progenitor cells and migrate into the developing CNS during early embryogenesis. Unlike other glial cells such as astrocytes and oligodendrocytes that originate from the neuroectoderm, microglia derive from the mesoderm, specifically the yolk sac [3, 4, 5, 6]. Under the influence of a variety of signaling molecules, microglia undergo a complex process of differentiation and maturation [7]. Mature microglial cells have a highly differentiated morphology and are constantly monitoring their microenvironment [8, 9, 10, 11].

Microglia are involved in a variety of physiological processes, including synaptic pruning, phagocytosis of cellular debris and regulation of neuroinflammation [12, 13, 14, 15]. In response to insults, microglia transform from a ‘resting’ state into an ‘activated’ state, changing their morphology, proliferating and producing a variety of inflammatory cytokines. Recently, the role of microglia involved in pain have been increasingly studied and in this review, they will be discussed in the acute and chronic pain state and in pain management.

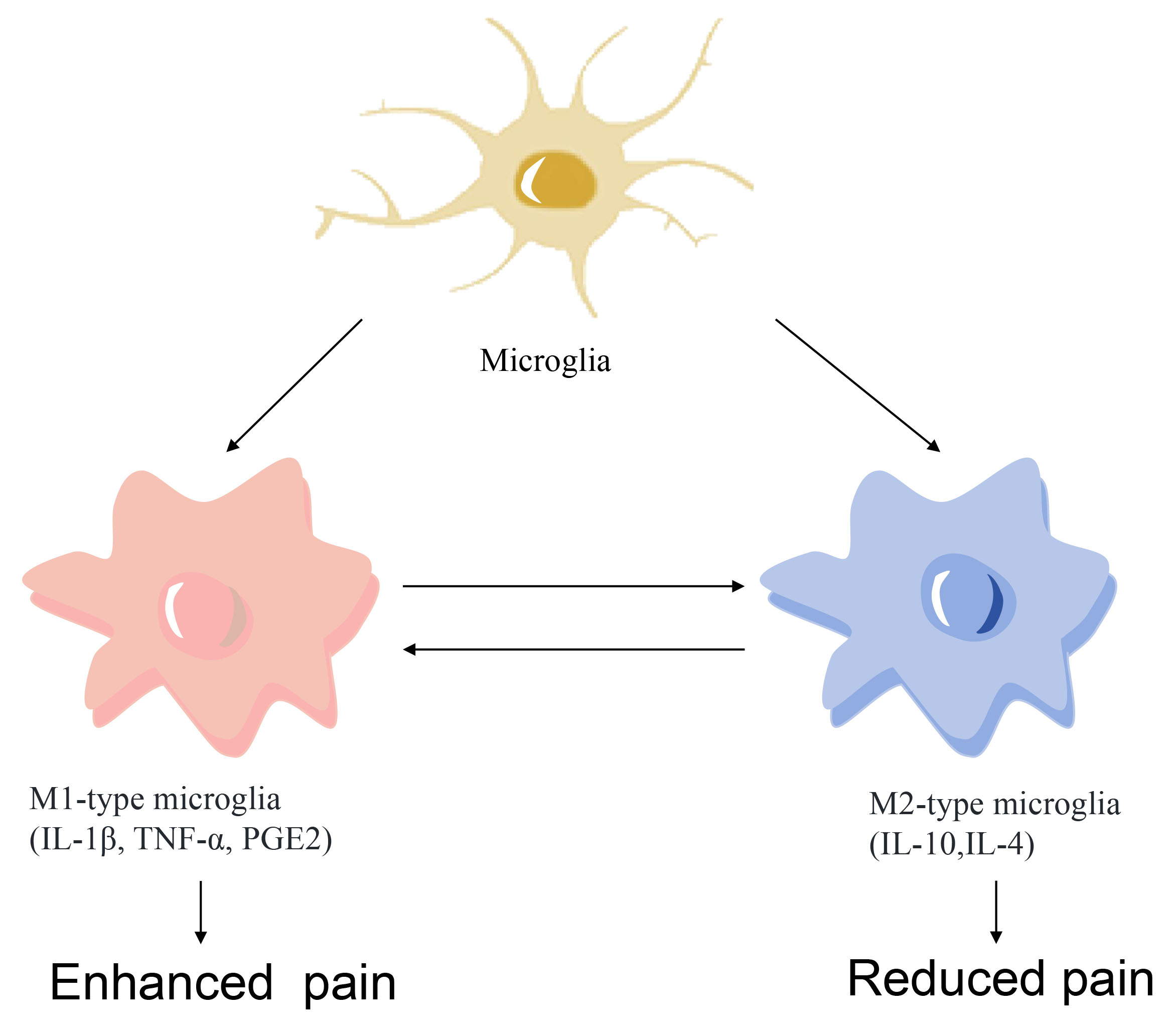

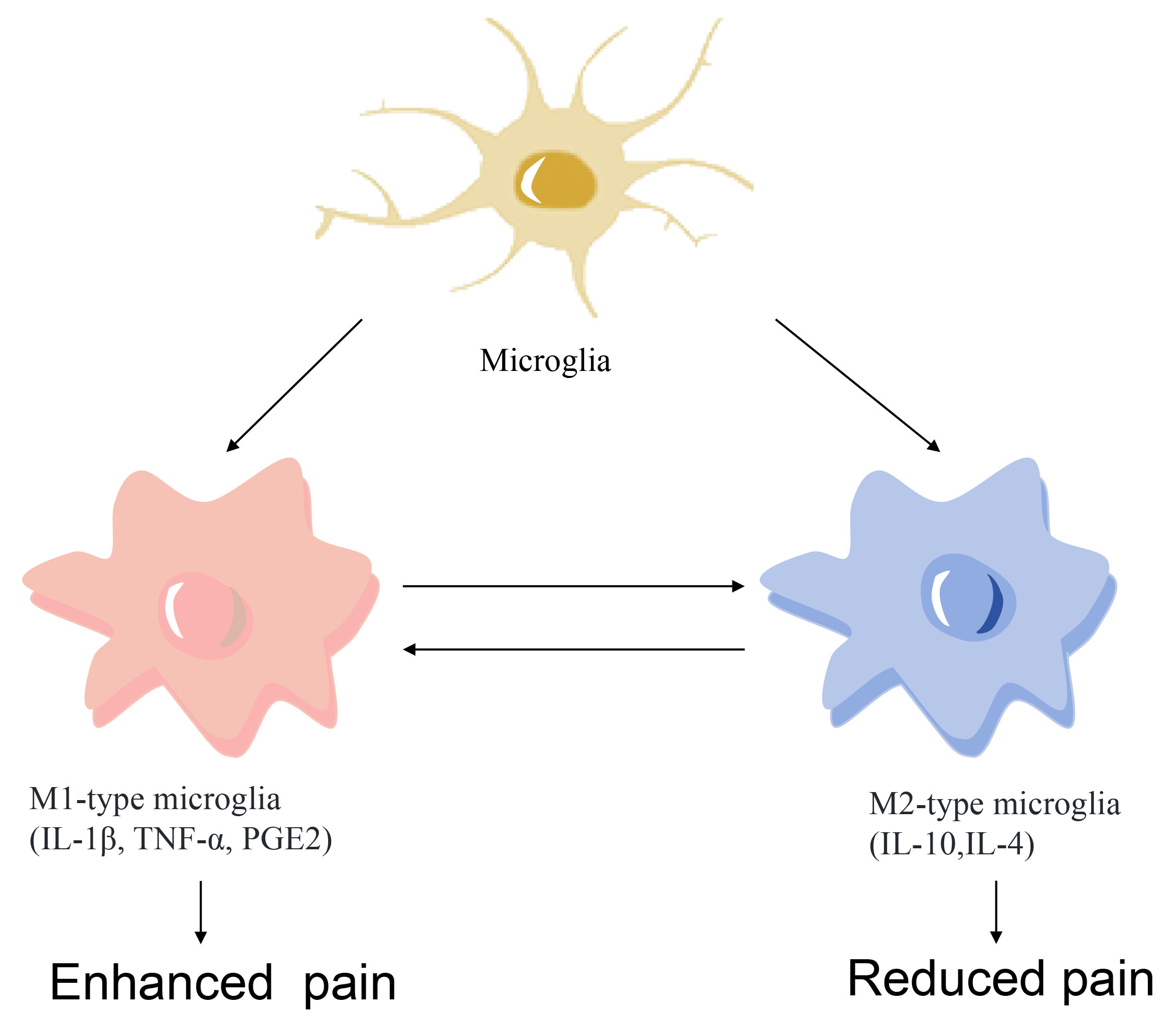

Microglia maintain the CNS homeostasis continuously and polarize to different phenotypes according to the insult. Previous study has demonstrated that microglia can be classified into either an M1 (pro-inflammatory) or an M2 (anti-inflammatory) phenotype, providing a useful framework for understanding their diverse functions (Fig. 1). M1-type microglia express cell-surface markers CD86 and CD68 and release inflammatory mediators, such as nitric oxide (NO), tumor necrosis factor-

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Microglia polarization to M1 (pro-inflammatory) and M2 (anti-inflammatory) phenotypes. TNF-

Under normal conditions, microglia remain in a ‘resting’ state, when their cell bodies are small and highly branched, constantly detecting the CNS microenvironment and eliminating all possible threats such as pathogens, abnormal injuries and damaged cells [22, 23]. In response to injury or infection, microglia rapidly activate and change from a highly branched state to an amoeboid state, expressing and secreting a variety of immunomodulatory factors such as cytokines, chemokines and antigen-presenting molecules [24, 25]. Activated microglia are able to kill pathogens directly by releasing toxic molecules such as glutamate and neurotoxins, while excessive inflammation may also lead to neuronal damage.

Alternatively, microglia activation results in anti-inflammatory polarization, reducing pro-inflammatory cytokine production and promoting tissue repair [26]. For example, IL-10, released from M2 microglia, inhibit the activity of M1-type microglia and reduce the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, thereby reducing the intensity of the inflammatory response. Elimination of overproduced reactive oxygen species (ROS) under hypoxic conditions block the nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-

Although much research has demonstrated a role for microglia in perioperative pain, recent studies have revealed their critical role in acute pain modulation. In the event of injury, peripheral nerve fibers receive incoming pain stimuli from nociceptive fibers and transmit integrated information to a central terminal in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. There, microglia proliferate rapidly and upregulate the expression of various genes associated with pre-injury perception pathways [28]. Chronically high concentrations of activated microglia are involved in the development of nociceptive hypersensitivity, not only by morphological and cellular functional changes, but also by the release of pro-inflammatory factors such as IL-1

Following damage to peripheral nerves, microglia in the spinal cord are significantly activated [35]. This activation process is dependent on neuronal activity [36]. Although activation of C-fibers is a key factor in triggering the activation of microglia, activation of large A-fibers is equally critical for sustained microglia activation. While microglia activation signals are initially released by primary sensory neurons, a variety of signaling molecules released from injured primary afferent nerves are decisive for the proliferation of spinal microglia and the development of neuropathic pain. Two studies [35, 37] have showed that peripheral nerve injury rapidly elevates colony-stimulating factor 1 (CSF1) expression in damaged dorsal root ganglion neurons. The CSF1 released by damaged primary afferent nerves, promotes the proliferation of microglia in the spinal cord by acting on them and contributes to the onset of painful behaviors. A study applying quantitative real time polymerase chain reaction methodology concluded that it was necessary for CSF1-CSF1 receptor (CSF1R)-triggered up-regulation of pain-associated microglia genes and the ensuing neuropathic pain condition [35]. Ab initio induction of CSF1 in injured sensory neurons triggers the expression of dorsal spinal cord neuropathic pain-associated microglia genes and also the subsequent neuropathic pain condition. DNAX-activating protein of 12 kDa (DAP12), central to adult microglia function [38], is located downstream of CSF1 receptor (CSF1R) and notably DAP12 is also a proinflammatory cellular factor induced by hypoglossal nerve injury cytokine (including M1 phenotypic markers) expression [39]. Finally, in rats, it has been found that the DAP12 mechanism also contributes to persistent neuropathic pain. Concurrently, disruption of the perineuronal network by microglia reduces inhibitory synaptic inputs, decreasing the activity of projection neurons and pain-related behaviors. Additionally, microglia are involved in neurotransmitter metabolic processes, e.g., by removing excess excitatory neurotransmitters and are involved in regulating neurotransmitter concentrations in the synaptic cleft, which in turn affects pain signaling [40].

In conclusion, microglia play a complex role in acute pain, participating in the generation, development and even amplification of pain. Therefore, understanding the specific mechanisms of the physiological and pathological roles of microglia in acute pain is important for the development of new pain treatment options.

Additionally, to acute pain, microglia exert a very important role in postoperative chronic pain. In animal pain models, nerve injury induces persistent nociceptive hypersensitivity, which involves the activation of inflammatory mediators (including hydrogen ions, potassium ions, bradykinin, prostaglandins and cytokines, such as IL-2, IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-

A study by Kohno et al. [46] found in a mouse pain model that an emerging CD11c microglia is involved in the maintenance of neuropathic pain. Microglia exhibit anti-injury functions by releasing anti-inflammatory mediators such as insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1). Microglia are the first to respond to neuronal firing activity during a damaging stimulus. Microglia recruit, proliferate and generate an excessive neuronal activity associated with pain recession. In brain development and disease, CD11c microglia emerge during homeostatic disturbances to oversee the health of the brain microenvironment by increasing phagocytic potential [47]. During the maintenance phase of pain, CD11c microglia express anti-injury resistance while releasing IGF-1 in response to anti-injury hypersensitivity. Thus, IGF-1 derived from CD11c+ microglia are essential for the spontaneous relief of neuropathic pain. When the paw withdrawal threshold returns to basal levels, depletion of CD11c+ microglia by intrathecal injection of an inhibitor leads to a recurrence of pain hypersensitivity. The intensity of an injury caused by surgery induces both peripheral and central sensitization, leading to a state of persistent pain. Peripheral sensitization is closely associated with the development of persistent pain and nerve growth factor, IL-1

In response to repeated chronically painful stimuli, interneurons that would otherwise play an inhibitory role undergo apoptosis. Loss of inhibitory interneurons results in uninhibited receptor excitation and lower pain thresholds. Simultaneously, synapses in glial cells undergo remodeling, leading to reduced signaling inhibition and increased synaptic efficiency, thus contributing to a state of neuroplasticity. Additionally, there is a mechanism involving the phenomenon of entanglement, in which repetitive low-frequency C-fiber stimulation leads to a progressive enhancement of action potential generation in the corresponding spinal cord region. The foregoing reveal a role for microglia in the transition from acute to chronic pain after surgery. Microglia play a critical role in the modulation of pain signals.

Other studies have revealed that spinal cord microglia in male mice exhibit a more pronounced acute inflammatory response than females after chronic compression nerve injury (CCI) and spare nerve injury, a sex-specific gene expression signature that is strongly correlated with temporal specificity [48, 49]. The theory in the past has been that nociception at sites of injury or inflammation was transmitted in the nervous system via microglia. In new study, only male mice fit this theory and interfering with the function of microglia effectively blocks nociception in males, but has no effect on females. It is a completely different class of cells (T cells) that transmit nociceptive signals in female mice [50]. This sex difference is particularly evident in the degree of microglia activation, with males experiencing sciatic CCI typically recovering from neuropathic pain more rapidly than female mice, which is consistent with the faster rate of recovery from nerve regeneration and abrogation of mechanically abnormal pain in male mice [51]. Those studies also reveal the possibility of treating pain by modulating the polarization state of microglia, providing an evidenced basis for the development of new pain management strategies.

Given the widespread use of opioids in pain management and their potential role in addiction and tolerance, the interaction between microglia and opioid drugs has been a focal point of research in the field of pain [52, 53].

Opioid drugs significantly influence the activation and function of microglia. Opioids induce a state of microglia hyperactivation through key mediators such as Toll-like receptor 2 [54], microglial ATP receptor P2X4 (a purine receptor subtypes) [55] and CSF1R [35], leading to an increase in the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as NO, TNF-

Alternatively, microglia similarly affect drug effects. Neurotransmitters and other signaling molecules are released by activated microglia and express opioid receptors, which in turn affect the analgesic effects of opioids [59]. For example, as microglia continue to release pro-inflammatory factors after the body has ingested opioids for a long period of time, this leads to opioid tolerance and hyperalgesia [60]. Over time, the body developss tolerance and dependence. Furthermore, the study has shown that inhibition of microglia activation attenuates opioid tolerance and addiction, thus providing new therapeutic strategies to address these issues [61]. In contrast, the novel µ-receptor agonist, MEL-0614, inhibits microglia activation and the subsequent upregulation of proinflammatory factors both in vivo and in vitro. Notably, this effect was partially mediated by the µ receptor [62].

The interaction between microglia and opioids is a complex process which not only affects the pharmacological effects of opioids but also their side effects. A detailed understanding of the process of their interaction could help to develop more optimal analgesic strategies and in turn, reduce the risk of opioid tolerance and hyperalgesia. With in-depth studies of microglia and their opioid-listed receptors, it is hoped that further advances will be made in opioid therapy for pain.

Microglia research in the field of pain has made significant progress but is not without its challenges. One of the primary difficulties lies in the complexity of microglial biology. Microglia are highly dynamic cells that are able to rapidly change their morphology, function and gene expression profiles in response to a variety of stimuli [63, 64, 65, 66]. Understanding the complexity of these changes and their implications in pain is a significant task. Additionally, it is difficult to isolate microglia from other brain cells, which poses substantial problems for the study of the various microglia functions [67]. Separation from tissue leads to activation or inhibition of some of their genes, changes in functional characteristics, and cause complex outcomes in research projects. Consequently, conducting in vivo research may avoid these issues. Moreover, the translation of findings from animal studies to humans is also a great challenge. Although animal models have been instrumental in advancing the understanding of microglia, they may not fully recapitulate the complexities of human microglial biology and disease states.

The development of new technologies and methods will likely drive future research on microglia. For instance, single-cell sequencing technologies could provide unprecedented insights into microglial heterogeneity and dynamics [65, 68, 69], while advanced imaging techniques could allow for real-time visualization of microglial behavior in vivo. Techniques related to the use of brain imaging to observe the expression of microglia activation sites in healthy individuals and patients with Alzheimer’s disease have been well established [1, 8, 70]. However, the heterogeneity of microglia across different brain regions and individuals also adds considerable complexity. Recent study has revealed that microglia exhibit distinct phenotypes depending on their location within the brain and an individual’s age, sex and health status [71]. These variations have significant implications for investigation the role of microglia in various pains [72].

The application of microglia research for drug development and clinical treatment is a promising yet challenging area. Microglia-targeted therapies offer new avenues for pain management and improving anesthesia outcomes. It is worth noting that microglia may differ in function and response in different species, which makes data obtained from animal models uncertain when translated to human clinical applications. Further, the relationship between microglia and pain involves multiple signaling pathways and molecular events and the complexity of these mechanisms makes it difficult to clarify their specific roles in pain modulation. Despite the fact that microglia activation is associated with the development of acute and chronic pain, no clinical therapeutic strategy has been identified to treat acute and chronic pain by targeting microglia. Despite these challenges, the future of microglia research in the fields of anesthesia and pain is promising. With continuous investigation of the intricacies of microglial biology, advances could significantly enhance the possibility of improving perioperative complications, with ultimate benefit to many patients.

The role of microglia in the field of pain is complex and varied, influenced by a wide range of factors and substances within the central and peripheral nervous systems. However, it is impractical to limit research to the role of microglia alone. Inhibition of the development of nociceptive sensitization has been shown to inhibit the development of nociceptive sensitization from a single inhibition of microglia activation or enhancement of the anti-inflammatory properties of activated microglia. Surgical trauma and opioid application activate microglia to varying degrees, triggering neuroinflammation, nociceptive sensitization and even increasing the probability of opioid tolerance occurring. Although the pro-inflammatory effects of microglia are well known, with further research their alternative functions have gradually been revealed. Although the concept of pain treatment is being updated and optimized every year, the development of personalized and specific treatments is urgent, thus insights into microglia-opioid interactions are essential for the development of new drugs and new pain treatment strategies.

CNS, central nervous system; NO, nitric oxide; TNF-

XRG design and supervised the study; XRG, SNS contributed to conceptualization, drafting and critical revision of the manuscript. Both authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. Both authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research was funded by Natural Science Foundation of Hubei (2023AFD041).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.