1 Department of Neurosurgery, Xuanwu Hospital Capital Medical University, 100053 Beijing, China

2 Clinical Research Center for Epilepsy Capital Medical University, 100053 Beijing, China

3 Beijing Municipal Geriatric Medical Research Center, 100053 Beijing, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Neuroregulatory therapy, encompassing deep brain stimulation and responsive neurostimulation, is increasingly gaining attention for the treatment of drug-resistant temporal and occipital lobe epilepsy. Beyond the approved anterior nucleus of the thalamus, the pulvinar nucleus of the thalamus is a potential stimulation target. Through a confluence of animal studies, electrophysiological research, and imaging studies, the pulvinar has been identified as having extensive connections with the visual cortex, prefrontal cortex, limbic regions, and multimodal sensory associative areas, playing a pivotal role in multisensory integration and serving as a propagation node in both generalized and focal epilepsy. This review synthesizes recent research on the pulvinar in relation to cortical and epileptic networks, as well as the efficacy of neuroregulatory therapy targeting the pulvinar in the treatment of temporal and occipital lobe epilepsy. Further research is warranted to elucidate the differential therapeutic effects of stimulating various subregions of the pulvinar and the specific mechanisms underlying the treatment of epilepsy through pulvinar stimulation.

Keywords

- pulvinar

- visual cortex

- occipital lobe epilepsy

- temporal lobe epilepsy

- neurostimulation

- neuromodulation

Epilepsy is a pervasive chronic neurological disorder with a prevalence of 1.5% to 5% [1], affecting an estimated 40–70 million people globally [2, 3, 4], which is approximately 1% of the global population [5, 6]. Among these, approximately one-third of patients’ seizures cannot be controlled by two or more appropriately chosen anti-seizure medications or other therapies [6], a situation known as drug-resistant epilepsy [5, 6, 7]. The sudden unexpected death in epilepsy risk is 1/1000 patient-years [8].

Although surgical treatment is a viable option for patients with identifiable epileptogenic foci, it has considerable limitations, such as epileptogenic foci located in motor or speech areas [9] and low acceptability [6, 10]. According to data from the United States, 1 in 500 individuals with drug-resistant epilepsy undergo resective epilepsy surgery annually [11]. Neurological impairment was more common in the postoperative group of focal resective epilepsy surgery. Sherman et al. [12] discovered that postoperative verbal memory impairment was observed in 44% of patients who underwent left temporal lobectomy and 20% of patients who underwent right temporal lobectomy. After surgery, 34% of patients with left-sided resections had difficulties with naming objects [12], 4%–18% experienced depression and 3%–26% experienced mild anxiety [13, 14]. In a study of 21 patients, Tandon et al. [15] discovered that 17% of patients with occipital lobe epilepsy experienced new quadrant blindness or hemianopsia after occipital lobe resection. Based on the numerous postoperative neurological dysfunctions associated with surgery, the benefits of neurostimulation therapy in the treatment of epilepsy have been studied [16].

Neurostimulation therapy is an essential treatment for epilepsy [17] and has the potential to provide more accurate and controllable treatment alternatives while being minimally invasive [18, 19, 20, 21]. In the United States, three types of neurostimulation are now licensed for the treatment of epilepsy: vagus nerve stimulation, responsive neurostimulation (RNS) [22, 23, 24] and deep brain stimulation (DBS) [25, 26, 27]. DBS is a successful treatment for some patients with intractable epilepsy, with studies showing that seizures can be decreased by more than 70% after 5 years, while only the anterior thalamic nucleus is currently approved as a stimulation target [28, 29, 30, 31]. The thalamus contains numerous key targets for DBS, the most promising of which are the anterior thalamic nucleus [32], median central nucleus [33], medial dorsal nucleus and pulvinar. Only anterior nucleus of the thalamus deep brain stimulation (ANT-DBS) has been investigated in prospective study [34].

As the largest nucleus in the thalamus, the pulvinar has attracted increasing interest because of its potential as a target for electrostimulation. Non-human primate studies of Otolemur garnettii and macaques have respectively confirmed that the pulvinar has connections with the visual system and association cortex [35, 36]. It is essential in various physiological functions, such as vision, attention regulation, working memory and emotional regulation [37, 38, 39, 40]. Rosenberg et al. [41] used stereoelectroencephalography (SEEG) data from 14 individuals with temporal lobe epilepsy to confirm the involvement of the medial pulvinar in the pathophysiology of temporal lobe epilepsy. Based on the findings of this study, the pulvinar is a promising target for electrical stimulation. This review aims to highlight the advances in pulvinar stimulation as an effective and safer alternative in treating drug-resistant epilepsy, providing hope for improved outcomes and reduced postoperative complications associated with conventional surgical interventions.

The thalamus is an essential region of the human central nervous system, which

has extensive connections with the cerebral cortex and participates in

information integration across cortical networks [42, 43, 44, 45]. It also maintains the

modularity of cortical functional networks, earning it the title of the

“comprehensive center” of functional brain networks. In addition to

transmitting high-fidelity information to and across cortical regions, thalamic

networks convey and maintain functional relationships within and across various

cortical regions. This thalamic network rapidly coordinates spatially segregated

cortical computations to create task-related functional networks [46]. The

thalamus has also been suggested as a source of transmission for generalized and

focal epilepsy [47, 48, 49, 50]. Guye et al. [51] investigated patients with

temporal lobe epilepsy who underwent preoperative assessment using a statistical

measure of SEEG signal correlation (nonlinear correlation). Correlation between

signals (or cross-correlation) recorded from the hippocampus, entorhinal cortex,

neocortical temporal cortex and thalamus (mainly the medial pulvinar group or the

posterior part of the dorsomedian nucleus) was estimated as a function of time by

using non-linear regression analysis. Through the analysis of the mean and

standard deviations of all interactions in each studied period, they discovered

an overall increase in synchronicity between the thalamic and temporal lobe

structures during seizures. Pizzo et al. [52] also examined SEEG records

and thalamic electrode samples from a group of patients with epilepsy (74

patients, 157 seizures). They explored nuclei include the pulvinar (42/74

patients), median nuclei (8/74 patients), lateral nuclei (16/74 patients) and

discovered that the thalamus played a role in the seizures in 86% of patients

(by visual analysis) and 20% of patients were hyperepileptogenic, whose

epileptogenicity index was higher than 0.3. Extension of the epileptogenic

network was associated with thalamic epileptogenicity (p = 0.02,

The pulvinar is the largest thalamic nucleus located on the medial and dorsal sides of the lateral geniculate nucleus, the most posterior nucleus of the thalamus. The pulvinar is divided into lateral, medial and inferior regions. The lateral pulvinar is primarily linked to the extracorporeal visual area and somatosensory circuit. The medial pulvinar is connected to all cortical regions, especially the frontoparietal network. The inferior pulvinar is linked to the early visual areas and auditory circuits. The pulvinar is essential in multi-sensory integration, with numerous sensory modes coexisting, including vision, hearing, smell, taste, pain and proprioception [54, 55, 56]. Rosenberg et al. [57] studied the intracerebral evoked responses obtained after electrical stimulation of the medial pulvinar and cortical regions in seven patients with epilepsy who underwent deep electroencephalography (EEG) recordings. They assessed the mutual functional connections between the medial pulvinar and cortical regions. Cortical evoked potentials for medial pulvinar stimulation were reported in all the cortical areas investigated except in the striatum, anterior cingulate gyrus and posterior central gyrus. The percentage of cortical contact pairs responding to medial pulvinar stimulation was 80% in the temporal neocortex, temporoparietal junction, mesial temporal region, insula and frontoparietal manipulation layer, 34% in the mesial temporal regions and 14% in the insula and frontoparietal manipulation layer. It was 67% in the temporal junction and 76% in the temporal neocortex. These findings provide evidence of extensive asymmetrical connections between the pulvinar and cerebral cortices [57]. By observing the evoked potentials, researchers also discovered that the anterior nucleus of the thalamus (ANT) was closely connected to the medial frontal lobe, lateral frontal lobe, anterior cingulate cortex, posterior cingulate and medial temporal lobe [58]. In contrast, the connections between pulvinar and cortical regions are more extensive.

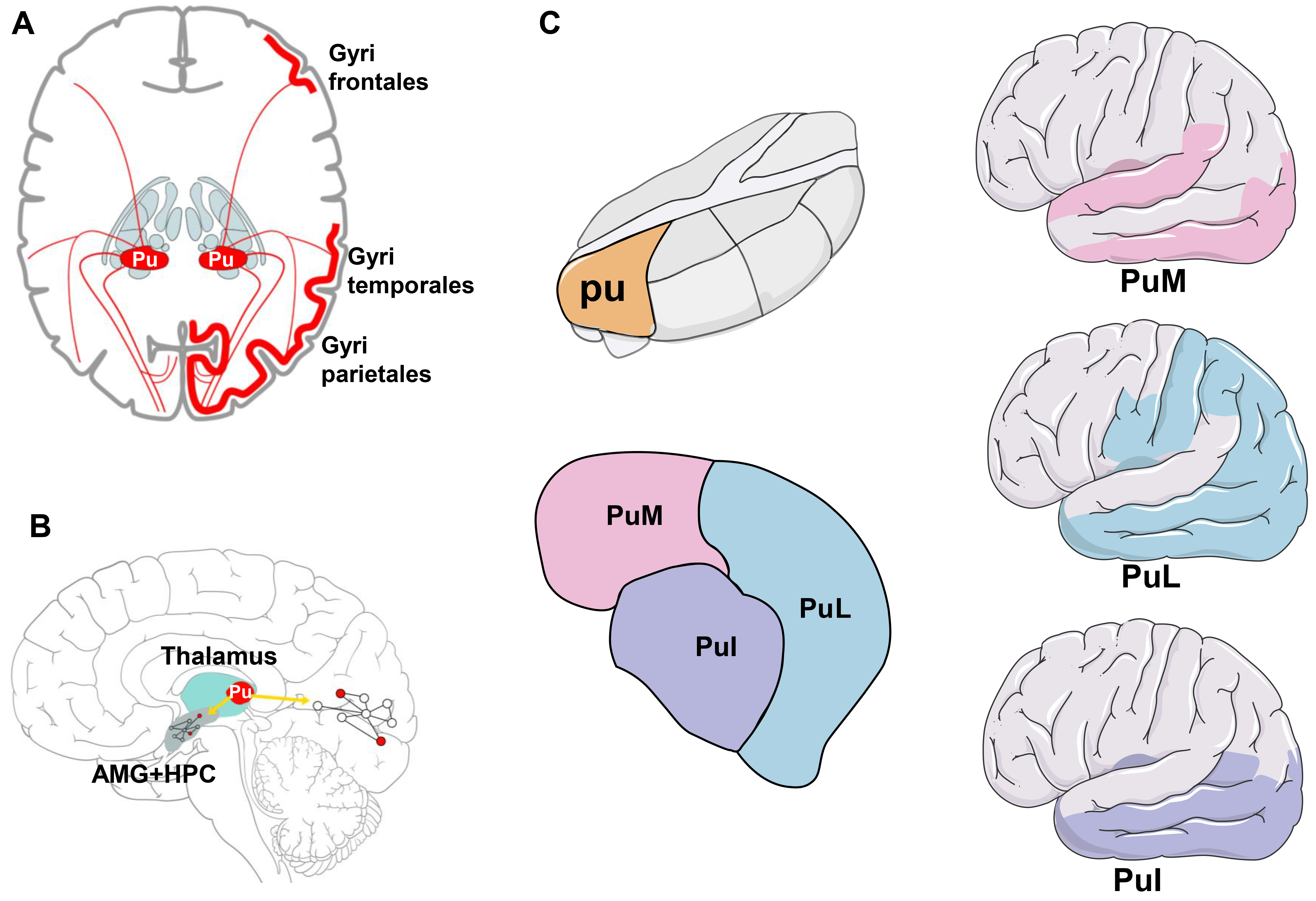

Many studies have verified the structural relationship between the pulvinar and the cortex as shown in Fig. 1 [54, 55, 56, 57]. In a study of 10 adult prosimian primates (Otolemur garnettii), Purushothaman et al. [35] evaluated the effect of the pulvinar on the upper layer of V1 particles projecting into the higher visual cortex (supra-granular layers of V1). They discovered that the lateral pulvinar could control and gate the information output of V1 effectively. Similarly, Romanski et al. [36] studied the connection between the pulvinar and prefrontal cortex in macaques. They discovered that the central/lateral pulvinar was connected to the posterior parietal regions 7a, 7ip, 7b, insular cortex, caudal superior temporal sulcus, caudal superior temporal gyrus and posterior cingulate gyrus in these primates. The anterior superior temporal sulcus, superior temporal gyrus, cingulate cortex and amygdala were associated with the medial pulvinar. These investigations show that distinct links between the central, lateral and medial pulvinars may underpin their functional circuits [36].

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Connections between pulvinar and multiple cerebral cortices. (A) There are extensive structural connections between the pulvinar and regions in the cortex, such as the temporal and parietal lobes. (B) Based on the connection between the pulvinar and brain lobes, the pulvinar may be involved in the regulation of a wide range of abnormal networks in the medial temporal lobe and occipital lobe. (C) The position of the pulvinar in the thalamus and the schematic diagram of the subnuclei, the right figure represents the cortex connected by each pulvinar subnucleus, and the color of the cortex corresponds to the color of the nucleus. Pu, pulvinar; AMG, amygdala; HPC, hippocampus; PuI, inferior pulvinar; PuL, lateral pulvinar; PuM, medial pulvinar. The figure was created using Adobe Illustrator CS6 (version 16.0.3, Adobe Inc., San José, CA, USA).

Many non-human primate investigations have also shown that the pulvinar is crucial for the regulation of vision, attention, working memory and emotion. Saalmann et al. [37] used diffusion tensor imaging to map the pulvinar-cortex network within the visual system, concurrently recording the spikes and field potentials of these interconnecting network sites while monkeys performed visuospatial attention tasks. They discovered that the pulvinar synchronizes the activities of interconnected cortical regions according to attention allocation, indicating that the pulvinar is essential in the regulation of attention selection and information transmission to the visual cortex. Jaramillo et al. [38] investigated the effect of the pulvinar on attention processing and working memory of the rhesus monkey. This was done using a pulvinar-cortical circuit model composed of the pulvinar and two cortical regions. They discovered that the pulvinar can change the operational mechanisms of these processes and resolve decision-making conflicts. Thus, the pulvinar plays a significant regulatory role in cognitive computing. Padmala et al. [39] investigated the role of the pulvinar in processing emotional stimuli using an attentional blinking task involving emotional stimuli during functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). According to research, the pulvinar plays an important role in emotion regulation via modulation of the limbic system [39, 40].

The pulvinar is now widely known as a major node of epilepsy transmission based on the following research.

In an electrophysiological study of 14 patients with intractable temporal lobe epilepsy, Rosenberg et al. [41] assessed the potential involvement of the medial pulvinar using SEEG during spontaneous temporal lobe epilepsy. Researchers observed medial pulvinar activity in 80% of the 74 seizures studied. The spread of seizures outside the seizure zone did not occur in the 15 patients without medial pulvinar seizures, whereas it occurred in 78% of the patients with medial pulvinar seizures. When medial pulvinar involvement correlates with the low-voltage fast activity, discharge transmission was systemically independent of the seizure area; however, discharge transmission accounted for only 66% of seizures when the medial pulvinar exhibited rhythmic slow-waves or rhythmic spikes. In conclusion, it was discovered that epileptic changes in medial pulvinar activity are frequently observed during temporal lobe seizures, implying that the medial pulvinar may play a role in epilepsy transmission [41]. For other nuclei of the thalamus, Kim et al. [59] confirmed concrete structural connections between the median central nucleus and medial frontal gyrus and anterior cingulate cortex from diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) data, which is related to seizure propagation. According to the SEEG research by Soulier et al. [53], both ANT and medial pulvinar (PuM) are highly connected with the mesial temporal region during temporal seizures, which indicate the involvement of those nuclei. In comparison, PuM also appeared to be the driver at the end of seizures with synchronous termination.

There is also substantial evidence from imaging studies showing that the pulvinar is involved in epilepsy. Szabo et al. [60] examined 10 individuals with complex partial status epilepticus using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), including diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and perfusion MRI (PI). On DWI, all patients showed regional high signals. Of these, some had reduced apparent diffusion coefficients in the hippocampus and pulvinar (6 out of 10 patients), pulvinar and cortical regions (2 out of 10 patients) and only the hippocampal structure (1 out of 10 patients). Alterations in pulvinar MRI were also found to be related to the temporal origin of seizures [61]. Sarria-Estrada et al. [61] discovered pulvinar involvement in 25.8% of 60 patients with epilepsy during an MRI investigation. Similarly, Capecchi et al. [62] examined the MRI data of 62 patients with focal status epilepsy. They discovered that medial pulvinar DWI was affected in 22 of them and that there was a strong association between the temporal lobe epileptic state and medial pulvinar DWI (18/33, 54.5%). According to these findings, the medial pulvinar appears to be a subcortical relay commonly implicated in the perpetuation of seizure activity in focal epileptic states with temporal lobe seizures. Barron et al. [63] used structural and diffusion MRI to assess the location and volume of the thalamic connection density in different medial temporal lobe (MTL) subregions. They discovered that the pulvinar consistently displayed the highest connection density to the hippocampus in both healthy controls and patients with medial temporal lobe epilepsy. Jo et al. [64] performed resting-state fMRI experiments on 17 patients with medial temporal lobe epilepsy and 17 controls. They obtained resting state functional connectivity (RSFC) maps of 70 thalamic nuclei seed masks and discovered that the medial pulvinar RSFC was closely associated with seizure frequency. In comparison, mediodorsal thalamic nuclei may play important roles in seizure activity or in the regulation of neuronal activity in the limbic system. The RSFC of motor- and sensory-relay nuclei may help elucidate sensory-motor deficits associated with chronic seizure activity.

Based on the above research results on pulvinar involvement in epilepsy networks, researchers have also investigated the pulvinar as a target for electrical stimulation for treating epilepsy as shown in Table 1 (Ref. [9, 65, 66]).

| Study | Subjects | Stimulating method | Type of study | Seizure recording method | Control or not | Parameter | Effects of seizure control | Side effect | Level of evidence |

| Filipescu et al. [65] | 8 patients (7 adults and 1 child) with temporal lobe epilepsy | PuM-stimulated by SEEG | Retrospective | 256‐channel DeltaMed system | Yes | 1–2 mA, 450 µs per pulse, 3–7 s duration, at the frequency of 130 Hz, 45 times totally during the interictal period (produced by a regulated neurostimulator designed for safe diagnostic stimulation of the human brain) | Significantly relieved from severe seizures (5/8); Significant reduction in mean tonic phase duration; No statistic differences in mean duration of seizures and the clonic phase | 1 sensorial (auditory) and 7 mild somatosensory responses were observed during high frequency stimulation and were well tolerated | IV |

| Burdette et al. [9] | 3 adult patients with regional neocortical seizure onsets in the posterior quadrant | Puv-RNS (The sub-nucleus is not mentioned) | Retrospective | SEEG recording | No | 0.2–2 mA, 2 s (patient 1 and 2) or 5 s (patient 3) duration, at the frequency of 125 Hz | No postimplant cognitive declines in any patient | IV | |

| Vakilna et al. [66] | 28-year-old male patient with temporal plus epilepsy | PuM-DBS | Retrospective | Seizure diary | No | 4 mA, 90 µs per pulse, at the frequency of 145 Hz delivered with a stimulation cycle of 1 min ON and 4 min OFF | 60% decrease in seizure frequency (follow up = 5 months) | Not mentioned | IV |

DBS, deep brain stimulation; PuM, medial pulvinar nucleus of the thalamus; Puv, pulvinar; RNS, responsive neurostimulation; SEEG, stereoelectroencephalography.

Filipescu et al. [65] confirmed the involvement of the pulvinar in epilepsy by evaluating the effect of medial pulvinar electrical stimulation in eight patients with temporal lobe epilepsy undergoing SEEG. The study found no significant difference in the mean duration of seizures after electrical stimulation compared with non-stimulation of the medial pulvinar in the 19 seizures produced. However, the duration of the tetanic period was considerably shorter in the cases with electrical stimulation. The study also discovered that seizures recovered faster in five of the eight individuals who received electrical stimulation of the medial posterior pulvinar compared with those with non-stimulated seizures, particularly in terms of altered consciousness. Patients with epilepsy recovered the fastest from high-frequency medial pulvinar stimulation (130 Hz, pulse width: 450 µs, duration: 3–7 s, current: 1–2 mA). Researchers believe that the effect of stimulation on recovery of consciousness is related to the effect of stimulation on thalamic and cortical connections. In a study of intracranial records of cortical and subcortical structures in 12 patients with persistent temporal lobe epilepsy, Arthuis et al. [67] discovered that the degree of loss of consciousness was related to the degree of thalamocortical system synchronization. The thalamus may play a role in controlling the corticocortical synchronization between distant brain regions. The thalamocortical system, which forms a reentry ring between the thalamus and cortical areas, is essential for conscious activity in the brain. Excessive synchronization can overburden the structures involved in the processing of consciousness, preventing them from processing incoming information and resulting in a loss of awareness [68, 69, 70, 71]. As loss of consciousness during temporal lobe seizures is caused by excessive synchronization between the thalamus and the association cortex (parietal and frontal lobes), electrical stimulation of the pulvinar may change this synchronization in patients [72]. The study by Filipescu et al. [65] had several limitations, including the small number of patients studied, inability to assess stimulation effectiveness reliably, inability to determine optimal stimulation parameters and inability to predict the long-term effects of electrical stimulation. Despite these limitations, it was the first study to suggest that electrical stimulation of the pulvinar may be a safe and effective neurostimulation therapy for drug-resistant epilepsy.

Vakilna et al. [66] reported a case of temporal plus epilepsy in which SEEG confirmed that the epileptic network involved both the medial temporal lobe and the right insula and imaging showed atrophy of the anterior thalamus, so the patient could not undergo traditional ANT-DBS or resection. Continuous monitoring of the PuM using spectral fingerprinting (12.15–17.15 Hz) showed that power spectral density changes in the local field potentials in the PuM reliably monitored seizures, while high-frequency DBS at 145 Hz significantly inhibited seizures in this patient, reducing seizures by 60% 5 months after PuM DBS implantation. This study confirmed that the pulvinar can reflect and regulate a broad network of cortical abnormalities. A potential protocol for patients with epilepsy who do not meet current surgical indications could be developed [66].

Burdette et al. [9] used pulvinar RNS to treat three patients with focal posterior quadrant regional neocortical epilepsy and followed them for 10, 12.5 and 15 months. This was the first study to use RNS to treat focal posterior quadrant regional neocortical epilepsy in the pulvinar area. At the last follow-up, all patients responded to electrical stimulation (50% reduction in disabling seizures), including two patients who had a 90% reduction in disabling seizures. None of the patients showed an implant-related neurocognitive decline in the neuropsychological tests but instead showed slight improvements in working memory, processing speed, reasoning, planning, problem-solving, and memory recognition (the third patient had only post-implantation neuropsychological test data). Extensive connections between the pulvinar and ipsilateral cortical regions are thought to provide effective neuroregulatory targets for refractory seizures in the structures of visual processing. They evaluated two patients using pulvinar depth leads via SEEG and discovered that the earliest EEG seizures occurred in the posterior quadrant leads, whereas early seizures spread to the pulvinar. This supported the involvement of the pulvinar in the epileptic network originating in the posterior quadrant. However, it is unclear whether stimulation of the pulvinar changes the network outside the posterior quadrant. This study has a few limitations due to the limited sample size. Larger multicenter investigations are required to draw conclusions regarding the safety and efficacy of the pulvinar-responsive neurostimulation system.

The efficacy of pulvinar DBS and RNS for treatment of temporal and occipital lobe epilepsy has been demonstrated in several studies [9, 66]. These studies assessed the effect of stimulation by means of neuropsychological scales or time-frequency quantitative analyses of field potentials, and from the point of view of seizure assessment and EEG spectral alterations, pulvinar electrical stimulation in the above studies provided effective seizure control. Among the currently used DBS targets, ANT is the most widely used for effective relief of focal and bilateral tonic-clonic seizures, whereas DBS of the centromedian thalamic nuclei (CMT) is more commonly used in generalized epilepsy. The mean seizure reduction rates after ANT, CMT and hippocampal DBS were 60.8%, 73.4% and 67.8%, respectively [32]. Clinical studies related to the pulvinar, as described above, are less well studied, but show better control of occipital lobe epilepsy. According to Vakilna et al. [66], due to the extensive connections between the pulvinar and the cortex, stimulation of the pulvinar is particularly suitable for the treatment of epilepsy involving an extensive network, such as bilateral hippocampal and right insular epilepsy, examined in the study. This makes full use of the extensive connection between pulvinar and cortex and provides a new treatment idea for epilepsy within an extensive network. Although there is no evidence from clinical trials at present, image connectomics studies have shown that different subdivisions of the pulvinar may have significant connections with different cortices [73]. More in-depth research is needed to establish if the lateral pulvinar or inferior pulvinar should be stimulated for occipital epilepsy [73]. And more tools on neurophysiology or brain network modulation are needed to explore the specific ways in which the pulvinar interferes with cortical epilepsy. Other forms of neuromodulation, as well as the development of personalized closed-loop therapies with embedded machine learning [74], are also directions worth considering.

Although the mechanisms of electrical stimulation of the pulvinar for treating epilepsy are unknown, previous studies on other DBS targets for epilepsy treatment have offered insights for further research in this area [6, 18, 32, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79]. Several animal experiments have suggested possible mechanisms of DBS that are multifaceted, including rebalancing excitation-inhibition, remodeling neural circuits, modulating epileptogenic networks, and mitigating neuroinflammation.

The underlying mechanism of DBS as an effective antiepileptic therapy is thought to involve modulation of underlying cellular inhibition or excitation within the target structure [6], which helps to interrupt the propagation of seizures or raise the overall seizure threshold, thereby reducing the frequency and severity of seizures. DBS prevents the onward spread of seizure activity by acting at important propagation points in the epileptogenic network [75]. Low frequency stimulation has been shown to restore normal neuronal electrical activity [18], whereas high frequency stimulation prevents the continued propagation of seizures by either directly inhibiting the target or by activating pathological activity in the disruption circuit [76]. In study of a rat slice model of the hippocampus, it has been found that high frequency stimulation enhances the inhibitory properties of epileptogenic networks and prevents the synchronisation and propagation of epileptiform paroxysmal discharges [77]. Taking the currently well-established target ANT as an example, several studies have found it to be an influential node in the epileptic network, essential for seizure maintenance and propagation [18, 32, 78, 79]. ANT modulates both the overall excitability of the thalamus cortex and the limbic seizure network [32], which is due to ANT connecting to the limbic system via the fornix and mammillary thalamic tracts, with broad and extended projections to the cingulate gyrus, medial cortex, hippocampus, orbital frontal cortex, and caudate nucleus, as well as projections through the circuit of Papez [78]. All these sites have been implicated in the pathogenesis of focal epilepsy. Disruption of this circuit may prevent the spread of seizure activity to the neocortex, and the neural network comprising these structures offers many other potential targets for intervention [18]. In addition, ANT-DBS can remotely modulate the excitability of neuronal networks through mechanisms such as inhibiting pathological electrical activity, reducing neuronal cell loss, suppressing immune responses, or modulating neuronal energy metabolism [79]. Overall, at the brain network level, DBS may inhibit abnormal activity by intervening at key nodes within the epileptogenic network, thereby interrupting potential epilepsy propagation. Future research could focus on the temporal characteristics of electrical activity propagation in different types of epilepsy to identify optimal intervention nodes and stimulation patterns.

The effects of DBS on neuronal circuits are multifactorial and complex. Study has shown that DBS has inhibitory effects and the mechanism for this inhibitory effect may be the blockade of depolarising and voltage-gated inactivation or the activation of gamma-aminobutyric acid-ergic (GABAergic) afferents in the nucleus accumbens [80]. However, it is not entirely clear whether the therapeutic effect of DBS is due to the stimulation of afferent inputs to neurons, glial cells, channel fibers or target neurons [81]. Additionally, some studies suggest that DBS affects the release of neurotransmitters such as glutamate and ATP from neurons or astrocytes [82, 83], thereby influencing the local excitatory-inhibitory balance. In summary, at the neural circuit level, DBS may activate GABAergic neurons or stimulate the release of various neurotransmitters, thereby inhibiting abnormal circuit activity. Future research could further explore the mechanisms by which electrical stimulation affects signal input and output between neurons and glial cells.

Neurostimulation can also inhibit or terminate seizure propagation by desynchronising epileptogenic networks. Seizures have been found to be associated with overexcitation and over-synchronisation of underlying neural networks, and desynchronisation of epileptogenic neural networks is an important mechanism for the efficacy of neurostimulation [84]. Low frequency stimulation interferes with synchrony between brain region, produces network stabilisation effects [85] and leads to long-term inhibition, resulting in a long-term decrease in synaptic efficacy [86]. High frequency stimulation is generally more effective in disrupting the propagation of synchronous neuronal activity [18]. All of these effects may reduce the excitability and synchronisation of the epileptogenic network, thereby suppressing spontaneous seizure activity. Neurostimulation can inhibit or terminate seizure propagation by desynchronizing epileptogenic networks, with low frequency stimulation producing long-term inhibition and high frequency stimulation disrupting synchronous neuronal activity, suggesting the need for future research to optimize stimulation parameters and better understand the desynchronization mechanisms involved.

In addition, some studies have investigated the neuroinflammatory mechanisms of

epilepsy treated with DBS. Chen et al. [87] discovered that DBS

reversed the elevation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-1

In summary, numerous studies have indicated that DBS targeting epileptogenic networks or key nodes may provide multiple mechanistic explanations at the brain network level, neural circuit level, local excitatory-inhibitory balance level, or from the perspective of neuroinflammation. Future research on the mechanisms of pulvinar-DBS regulation of epilepsy could also explore these aspects in depth.

Through continuous research, it has been found that the pulvinar has extensive connections with the visual cortex, prefrontal cortex, limbic regions and multimodal sensory associative areas, playing a pivotal role in multisensory integration and serving as a propagation node in both generalized and focal epilepsy. Animal experiments and clinical studies have reported that the pulvinar shows potential as an effective target of neurostimulation for temporal lobe and occipital lobe epilepsy. Although many studies have demonstrated the antiepileptic effects of pulvinar stimulation, the specific mechanisms are still unclear and more research is needed to understand how pulvinar stimulation is involved in the circuitry of epilepsy and play an anti-epileptic role.

ANT, anterior nucleus of the thalamus; DBS, deep brain stimulation; DWI, diffusion-weighted imaging; DTI, diffusion tensor imaging; fMRI, functional magnetic resonance imaging; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PuM, medial pulvinar nucleus of the thalamus; RNS, responsive neurostimulation; RSFC, resting state functional connectivity; SEEG, stereoelectroencephalography; SE, status epilepticus.

GZ designed the research study. BS and YD conceptualized and designed the study, designed the figure, performed the literature searches and drafted the manuscript. QL, CH, YW and PW collected the references and provided help and advice on the table and figure. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research was funded by Beijing Municipal Science & Technology Commission (Z221100007422016, Z221100002722007); Translational and Application Project of Brain-inspired and Network Neuroscience on Brain Disorders, Beijing Municipal Health Commission (11000023T000002036286); National Natural Science Foundation of China (82201605).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.