1 Health Neuroscience Collaboratory, College of Health Solutions, Arizona State University, Phoenix, AZ 85004, USA

2 Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843, USA

Neuroplasticity, or brain plasticity, refers to the brain’s ability to change, adapt, and reorganize itself by forming new neural connections throughout life. Several key factors contribute to neuroplasticity, including genetics, learning, training, and environmental changes. Experience-dependent neuroplasticity (EDN) represents the influence of a person’s life experiences (e.g., culture, learning, adversity, drugs) on brain development and reorganization [1]. In the London taxi driver study, compared to non-taxi-driver controls, the taxi drivers who mastered the city’s streets showed increased grey matter volume in the posterior hippocampus, a region crucial for spatial memory. The longer an individual had been driving taxis, the larger their posterior hippocampus [2]. However, daily experiences are often not self-motivated and are driven by external demands and tasks such as repeated environmental stimuli. Therefore, we propose self-directed neuroplasticity to consciously shape our brain’s structure and function,and effectively change habits and behaviors.

Self-directed neuroplasticity (SDN) refers to the modulation and reorganization of the brain’s plasticity through effortful and effortless self-control processes using self-initiated, tailored experiences (e.g., training) to induce brain functional and structural changes [1]. Compared to EDN which is closely linked to task-positive networks (e.g., sensory, motor), SDN engages down-regulation of default mode networks and up-regulation of self-control and task-positive networks [1]. There are two types of training methods—Network training and State training, which contribute to self-neuroplasticity [3]. In this review, we consider two widely used methods—working memory training and mindfulness training to demonstrate the similarities and differences between network and state training on brain plasticity.

Cognitive training has now become popular to improve cognitive function and prevent cognitive decline. It uses a set of structured, targeted activities designed to improve specific cognitive functions such as working memory and attention [4]. Network training often uses computerized programs (e.g., attention or working memory training) and involves task repetitions with increasingly demanding levels of task difficulty and effort. Network training requires narrow focus and task-specific learning and exercise. Therefore, it engages specific brain networks related to selected cognitive processes.

Working memory is the capacity to hold and manipulate information while resisting distractions. Working memory training (WMT) targets the temporary storage of a few items, either recently presented or retrieved from memory. Therefore, it specifically targets the structure of the task (like n-back working memory) and does not generalize beyond that task. The meta-analyses of WMT have shown significant near transfer in working memory but little to no far transfer to general intelligence, and academic skills [5, 6]. Several factors may contribute to limited far transfer including lack of overlap in core cognitive processes, not targeting executive functions, and lack of motivation and engagement. Thus, training-induced neuroplasticity tends to be task-specific (e.g., stronger activation in the frontoparietal areas related to the task), rather than broadly restructuring networks involved in other cognitive capacities [1, 3].

Why is frontoparietal plasticity task-specific? One explanation is the context-dependence of synaptic modifications in prefrontal and parietal regions, where long-term potentiation and long-term depression reinforce task-relevant circuits without broad generalizations [7, 8]. Basic mechanisms, such as synaptic pruning and the activity of brain-derived neurotrophic factors, further constrain plasticity to circuits that are repeatedly engaged [9]. Thus, while frontoparietal plasticity supports task performance, its specificity limits generalization beyond the trained task. These findings suggest that brain plasticity is localized following WMT [1, 3, 5, 6].

In contrast, state training uses practice (e.g., mindfulness meditation, nature exposure) to develop a brain state that may influence the performance of many networks. This state involves networks but is not designed to train networks using a cognitive task. Instead, it changes brain and bodily states (central and autonomic nervous system, CNS and ANS) and engages diverse brain networks such as attention control, emotion regulation, self-awareness, and executive function. It is different from effortful network training, such as WMT, that involves demanding cognitive tasks or processes to achieve benefits [3, 10].

Integrative Body–Mind Training (IBMT), an open-monitoring mindfulness practice, is an example of SDN. IBMT emphasizes effortless awareness of body and mind, accepting whatever arises without trying to control thoughts or feelings. Randomized trials show that brief periods of IBMT enhance attention and self-control, and induce neuroplasticity in the anterior and posterior cingulate cortex (ACC and PCC) and striatum through interaction between CNS and ANS. In addition, IBMT has shown far-transfer effects such as improvements in cognitive performance, academic skills, emotion regulation, executive function, and immune function [1, 10, 11, 12, 13].

Why does IBMT induce neuroplasticity through CNS and ANS interactions? Emerging evidence points to a bidirectional mechanism. IBMT increases parasympathetic activity (e.g., elevated high-frequency heart rate variability), which is associated with improved regulation of emotion and attention control. This heightened vagal tone provides a physiological context that facilitates ACC engagement, thereby modulating its activity [1, 10, 13]. Alternatively, IBMT directly modulates ACC activity and its functional connectivity with broader regulatory networks (e.g., insula, striatum, PCC). These networks are implicated in both cognitive control and autonomic regulation. This form of top-down regulation from the ACC to the ANS suggests a central–autonomic coupling mechanism that may underlie IBMT-induced neuroplasticity. These findings are consistent with previous studies documenting the role of ACC in autonomic regulation across both healthy and pathological populations [10, 13, 14, 15].

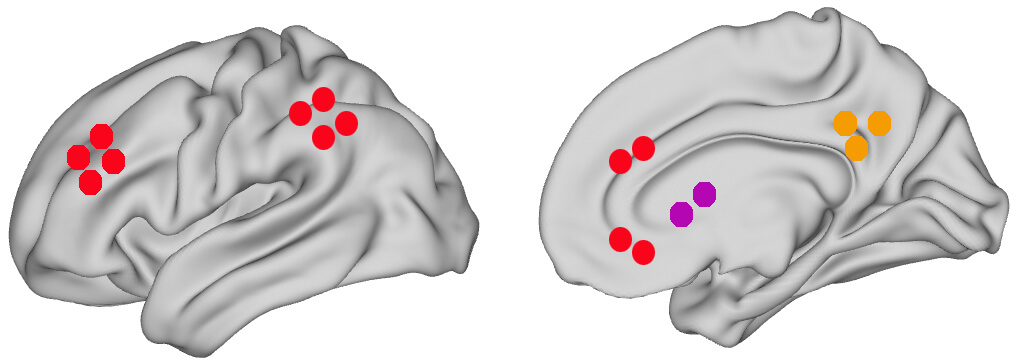

As shown in Fig. 1, effortful and effortless attention and self-control processes modulate and reorganize brain plasticity using self-initiated, tailored training experiences to induce functional and structural changes in the brain.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Biomarkers of self-directed neuroplasticity. Biomarkers include structural (e.g., grey matter volume) or functional (e.g., brain activity) changes. Key brain areas are involved in the effortful (left) and effortless (right) attention and self-control processes. The red, orange, and purple dots represent the frontoparietal areas (left), ACC, PCC, and striatum (right), respectively. ACC, anterior cingulate cortex; PCC, posterior cingulate cortex.

Effortful control involves sustained mental effort and control to achieve outcomes and is often supported by the frontoparietal network. Participants often don’t enjoy the training and seldom continue it voluntarily. Therefore, how to engage participants with greater interest and motivation in repetitive tasks is crucial for efficient plasticity [3]. In contrast, effortless control engages minimal effort and autonomic control and is often supported by the ACC, PCC, striatum and parasympathetic nervous system. Participants often enjoy and engage in the training. How to maintain a longitudinal practice voluntarily is important to the plasticity [10].

Effortful control requires narrow focus whereas effortless control engages open focus. When requiring paying attention to an object or a task, we often use narrow focus with a rigid and fixated attention mode to complete the task, which leads to elevated stress and muscle tension in the neck, head and spine. This process triggers effort-based frontoparietal areas and the sympathetic nervous system. When using an open, soft, and flexible attention mode to complete a task, we are in the parasympathetic dominance and engaging the ACC-PCC-striatum network, which is often more efficient and creative. Therefore, effortful control aligns with network training’s narrow focus, while effortless control underlies state training’s open focus. As a result, changing attention habits and balancing narrow and open focus become crucial for effective SDN [1, 10, 11, 12, 13, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20].

SDN can be brief and we can use designed experiences (e.g., training format) to modulate and reorganize our own brain function and structure through effortful and effortless attention and self-control processes. How to combine effortful and effortless training, such as in different time course or dose, is imperative for effective SDN and performance.

YYT and RT — Writing, Conceptualization, Original draft. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. Both authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This work is supported by the Office of Naval Research (N000142412270) and the National Institutes of Health (R33AT010138).

The authors declare no conflict of interest. Yi-Yuan Tang is serving as one of the Editorial Board members of this journal. We declare that Yi-Yuan Tang had no involvement in the peer review of this article and has no access to information regarding its peer review. Full responsibility for the editorial process for this article was delegated to Bettina Platt.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.