1 International Acupuncture and Moxibustion Innovation Institute, School of Acupuncture-Moxibustion and Tuina, Beijing University of Chinese Medicine, 100029 Beijing, China

2 Department of Acupuncture and Moxibustion, Dongzhimen Hospital, Beijing University of Chinese Medicine, 100700 Beijing, China

3 School of Life Sciences, Beijing University of Chinese Medicine, 100029 Beijing, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

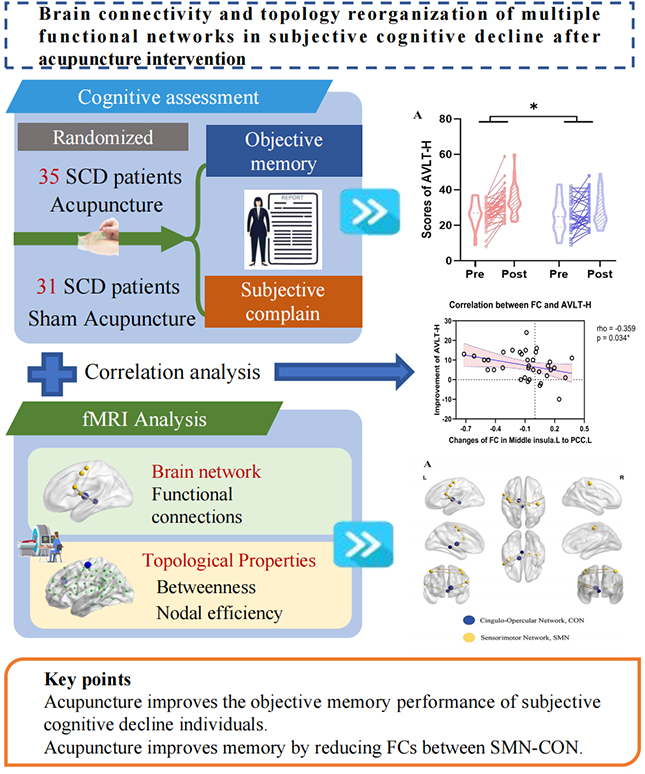

Evidence suggests that subjective cognitive decline (SCD) involves abnormal structures and functional alterations in multiple brain networks, rather than a single brain region. Acupuncture has shown a positive therapeutic effect in treating SCD, although whether and how it can improve cognitive decline by altering large-scale brain network organization is unclear.

We utilized resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) data from 66 individuals with SCD (derived from a previous randomized controlled trial) and explored brain-wide network-level functional connectivity and topological property changes after 12 weeks of acupuncture intervention to examine its therapeutic mechanisms. The Auditory Verbal Learning Test-Huashan version (AVLT-H) test was used to measure objective memory performance. Neuroimaging outcomes included brain network functional connectivity and topological properties obtained from resting-state fMRI. A repeated-measures general linear model and mixed-effect analysis were used to examine group × time interaction effects on cognitive function and neuroimaging outcomes. Correlation analyses were used to examine the relationship between functional connections (FCs) and memory performance.

Compared with sham acupuncture, 12 weeks of acupuncture treatment significantly improved the objective memory performance of individuals with SCD. Five FCs within the sensorimotor network (SMN) and between the SMN and the cingulo-opercular network (CON) showed significant alterations after acupuncture. Two intrinsic SMN connections were enhanced by acupuncture, whereas inter-network FCs changed oppositely, negatively correlating with memory improvement. The topological properties of two regions within the SMN were also significantly modulated after acupuncture.

The results suggest that 12 weeks of acupuncture may improve objective memory performance in SCD, potentially by reducing FCs between the SMN and CON. Enhancing functional segregation of these networks may be a potential target for acupuncture treatment.

No: NCT03444896. https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03444896.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords

- acupuncture

- topographic brain mapping

- functional neuroimaging

- magnetic resonance imaging

- cognitive decline

Subjective cognitive decline (SCD), also known as subjective cognitive/memory impairment/complaints, refers to a self-experienced decline in cognition among individuals with normal performance on standardized neuropsychological tests [1]. It is important to note that interventions during the SCD period may reduce the risk of development into objective cognitive decline or dementia [2]. Acupuncture, a promising non-pharmacological therapy, has the potential to treat multiple types or stages of cognitive decline [3, 4], with a better treatment prognosis especially in earlier SCD stages. For instance, 8 weeks of acupuncture or electroacupuncture treatment has shown promising effects on amnesic mild cognitive impairment (MCI) [5] and vascular cognitive impairment with no dementia [4]. Moreover, our previous research revealed that a 12-week course of acupuncture treatment improved the global cognitive function of individuals with SCD [6]. However, the neural basis for acupuncture intervention in SCD has yet to be fully investigated.

The neurobiological basis of multiple cognitive abilities is governed by two fundamental principles of human brain function: integration (i.e., the formation of large-scale brain networks through long-range functional connectivity) and segregation (i.e., the specialization of distinct regions through local differentiation) [7, 8]. Successful reconfiguration underlying better memory relies on the functional segregation, integration, and balance of large-scale resting brain networks [7]. Cognitive complaints may involve similar vulnerabilities in segregation and integration in large-scale brain networks [9]. A longitudinal study suggested that individuals with SCD with a greater decline in subjective cognitive function had lower functional connectivity within networks, although functional connections (FCs) between networks increased [10]. Patients with MCI have also been reported to exhibit abnormal FCs in multiple brain networks, including the sensorimotor network (SMN) and executive control networks [11]. Specifically, interruption of FCs within the SMN of MCI patients has been associated with decreased cognitive function [12] and deterioration of working memory and attention [11].

Brain connectivity and network topological analyses provide a powerful approach to quantify information communication and network efficiency, offering in-depth insights into the system-level mechanisms of brain network integration and segregation [13, 14]. Acupuncture has multi-target therapeutic effects [15] and network-based analysis has been widely adopted to uncover the complex mechanisms of acupuncture [14]. The regulatory effects of acupuncture on large-scale brain networks have been demonstrated in objective cognitive disorders [16]. A systematic review has summarized that the FCs of the default mode network (DMN), central executive network, and salience network can be regulated by acupuncture in patients with MCI [16]. However, whether and how acupuncture alleviates SCD symptoms by modulating the integration and segregation of large-scale brain networks remains an unexamined, crucial question.

Memory impairment is one of the major symptoms of SCD [17]. In the present study, we sought to examine changes in the large-scale brain network associated with memory improvements attributed to acupuncture, using resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) data from a previous randomized controlled trial (RCT) of acupuncture treatment in individuals with SCD [6]. Unlike previous seed-based functional connectivity analysis [6], in the present study we extracted time series from all brain regions using the Dosenbach atlas, constructed a functional connectivity matrix of the brain network, and examined alterations in FCs at the large-scale brain network level. Graph theory was subsequently applied to compare the topological properties of regions showing significant differences. Finally, correlations between these network changes and memory performance were evaluated to elucidate the central mechanisms of acupuncture in SCD. We hypothesized that acupuncture may alter memory in SCD by modulating large-scale resting-state brain network FCs and topological properties.

This study utilized data from a 12-week randomized, sham acupuncture-controlled trial based on multi-model magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data (ClinicaltTrials.gov ID: NCT03444896), which was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Beijing Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine affiliated with Capital Medical University.

Participant recruitment was conducted in Beijing Shunyi community service

centers from April 25, 2018, to October 20, 2018. Participants were screened

through the Subjective Cognitive Decline Questionnaire 9 (SCD-Q9, score

Participants received 24 sessions of 20 minutes of acupuncture or sham acupuncture treatment over 12 weeks (twice a week). Disposable needles (Hwato, Suzhou, Jiangsu, China), blunt-tip sham needles, and the SDZ Version V electro-acupuncture apparatus (Suzhou Medical Appliance, Suzhou, Jiangsu, China) were used. In the AG, participants received acupuncture at 14 acupoints, including Baihui (DU20), Shenting (DU24), Fengfu (DU16), Fengchi (GB20), Danzhong (RN17), Zhongwan (RN12), Qihai (RN6), Neiguan (PC6), Tongli (HT5), Xuehai (SP10), Zusanli (ST36), Zhaohai (KI6), Xinshu (BL15), and Yixi (BL45), and were required to achieve de-qi (feeling of soreness, numbness, heaviness). The electro-acupuncture apparatus was attached to the DU20 and DU24, which were stimulated for 20 minutes with a dilatational wave of 2–100 Hz and a current intensity of 0.1 to 1 mA. In the SG, participants received sham acupuncture at sham acupoints, which were away from any acupoints or meridians, with blunt-tip sham needles inserted into the adhesive pads rather than the skin [6]. Procedures and other treatment settings for the SG were similar to those for the AG, but the electro-acupuncture apparatus did not have any electricity output.

In this study, we focused mainly on the memory domain, which is most commonly affected in individuals with SCD [17, 21]. Multiple lines of evidence indicate that, except for subjective memory decline, individuals with SCD have lower objective memory [22, 23]. The AVLT-Huashan version (AVLT-H), which has good validity and reliability, was used to assess the learning and episodic memory of individuals with SCD [24]. AVLT-H is a delayed recall of a 12-word test that includes three immediate recalls, one short-term delayed recall (AVLT-H-S, with 3–5-min delay), one long-term delayed recall (AVLT-H-L, with a 20-min delay), and one recognition [24]. Both AVLT-H-S and AVLT-H-L are sensitive and effective in assessing memory function in older adults [25]. In the present study, the AVLT-H total score (sum of all correct responses in the five recall tests) was used to evaluate the objective memory performance in individuals with SCD; a higher score meant better objective memory performance [22].

Two MRI scans were performed within 1 week before and after treatments with a

3.0 Tesla scanner (Skyra, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) in the Beijing Hospital of

Traditional Chinese Medicine affiliated with Capital Medical University.

Resting-state fMRI was performed using an echo planar imaging (EPI) sequence:

Repetition time (TR) = 2000 ms; echo time (TE) = 30 ms; bandwidth = 2368 Hz/Px;

echo spacing = 0.5 ms; field of view (FOV) = 224

Resting-state fMRI data were preprocessed using the a toolbox for data

processing and analysis of brain imaging; (DPARSF, http://www.rfmri.org). The

preprocessing steps included removing the first 10 images, slice-timing, head

motion correction, and spatial normalization to the Montreal Neurological

Institute (MNI) space using the EPI template. The functional images were then

resampled into a voxel size of 3

To map the large-scale brain network mechanisms of acupuncture, we constructed a

whole-brain functional connectivity matrix and analyzed the network property

changes. The time courses of the 142 regions of interest (ROIs, radius of 5 mm,

including 19 voxels in each ROI) corresponding to Dosenbach’s template (excluding

the 18 ROIs of the cerebellum) [26] were extracted using MATLAB Version 2017 (The

MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA, USA) software and the DPABI Version 6.1 (Instituted

of psychology, CAS., Beijing, China) toolbox [27]. The brain network functional

connectivity matrix was generated by calculating Pearson correlations between the

time series of all ROI pairs (142

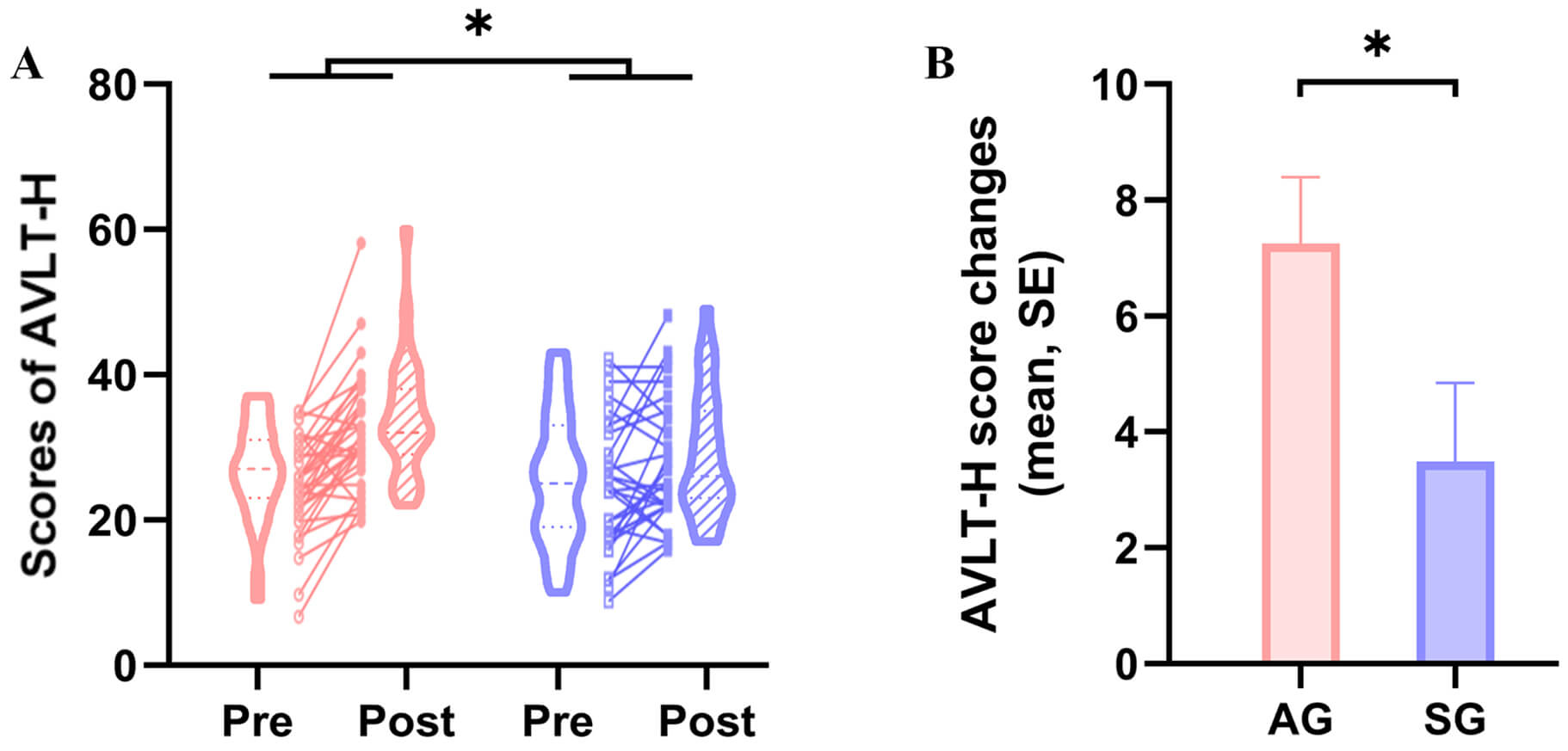

The group

There was a significant group

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Acupuncture effect on memory. (A) Significant acupuncture

effects were indicated by the AVLT-H score. (B) The mean and SE of AVLT-H score

changes at the end of the intervention for each group. * Indicates a significant

group

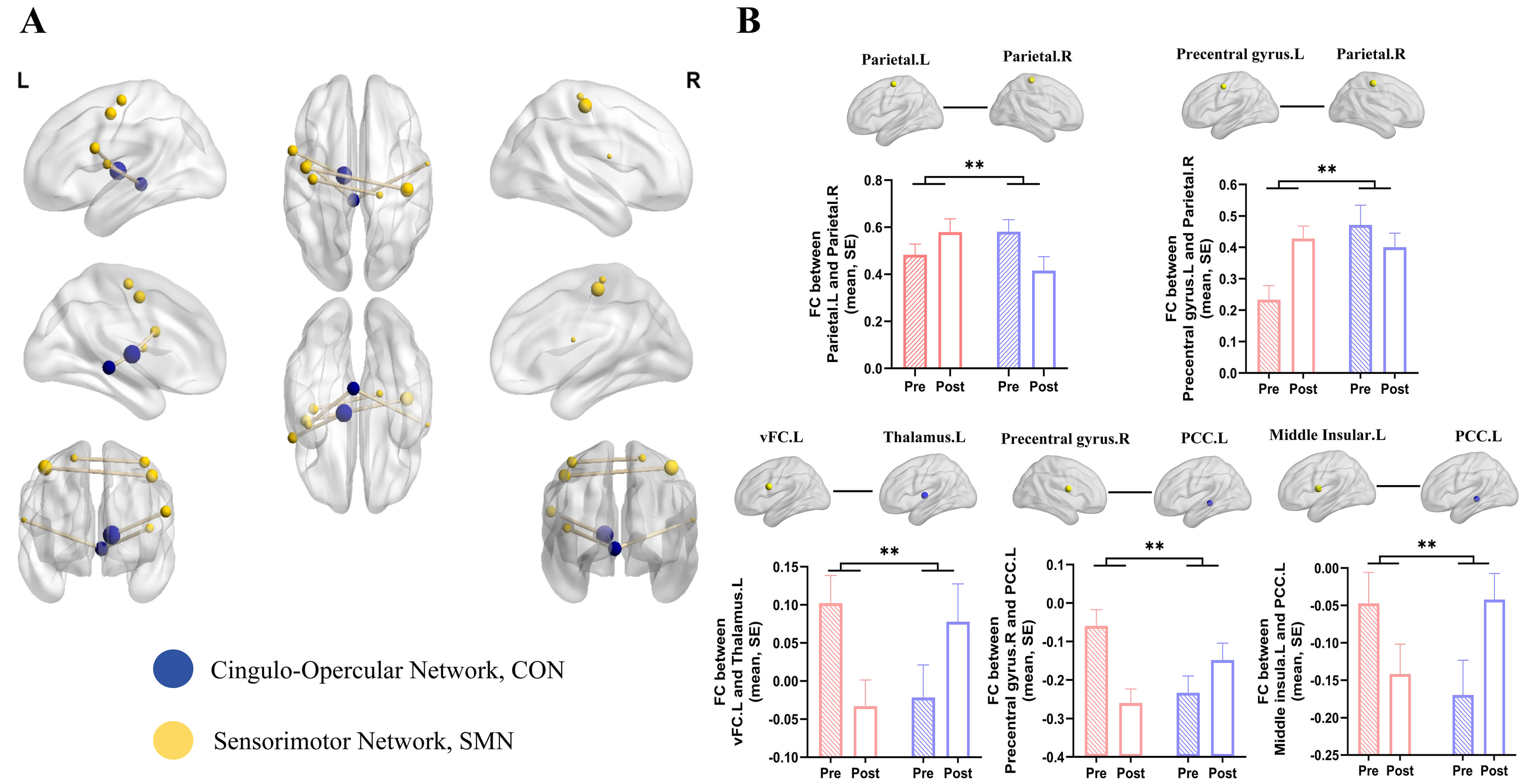

For brain network functional connectivity analysis, five functional connections

(nine related ROIs) exhibited a significant group

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Acupuncture effect on brain network functional connectivity.

(A) Significant group

For graph theory analysis, we mainly focused on the nine ROIs that showed

significant interaction effects according to brain network functional

connectivity analysis. The pre- and post-intervention AUC values for the key

topological properties of each ROI are shown in Supplementary Table 3. After

intervention, greater enhancements were observed in the AG than in the SG in the

nodal efficiency of the left parietal lobe (p

| Brain regions of interest | MNI coordinates (x, y, z) | Nodal efficiency AUC | Betweenness AUC | ||

| Interaction T value | p value (Group × Time) | Interaction T value | p value (Group × Time) | ||

| vFC.L | –55, 7, 23 | 0.859 | 0.394 | –1.016 | 0.309 |

| Precentral.gyrus.R | 58, –3, 17 | 1.130 | 0.263 | 0.287 | 0.783 |

| Middle.insula.L | –42, –3, 11 | 0.978 | 0.309 | –0.085 | 0.933 |

| Precentral.gyrus.L | –44, –6, 49 | 1.770 | 0.078 | –1.954 | 0.055 |

| Thalamus.L | –12, –12, 6 | 1.441 | 0.161 | –1.950 | 0.054 |

| Parietal.L | –38, –15, 59 | 2.652 | 0.009* | –1.257 | 0.206 |

| Parietal.R | 41, –23, 55 | 1.797 | 0.073 | –0.254 | 0.807 |

| Parietal.R | 18, –27, 62 | 1.282 | 0.190 | –3.281 | 0.001* |

| PCC.L | –4, –31, –4 | 1.282 | 0.210 | –0.206 | 0.842 |

Abbreviations: ROIs, regions of interest; MNI, Montreal Neurological Institute; AUC, area under the curve.

*indicates significant group

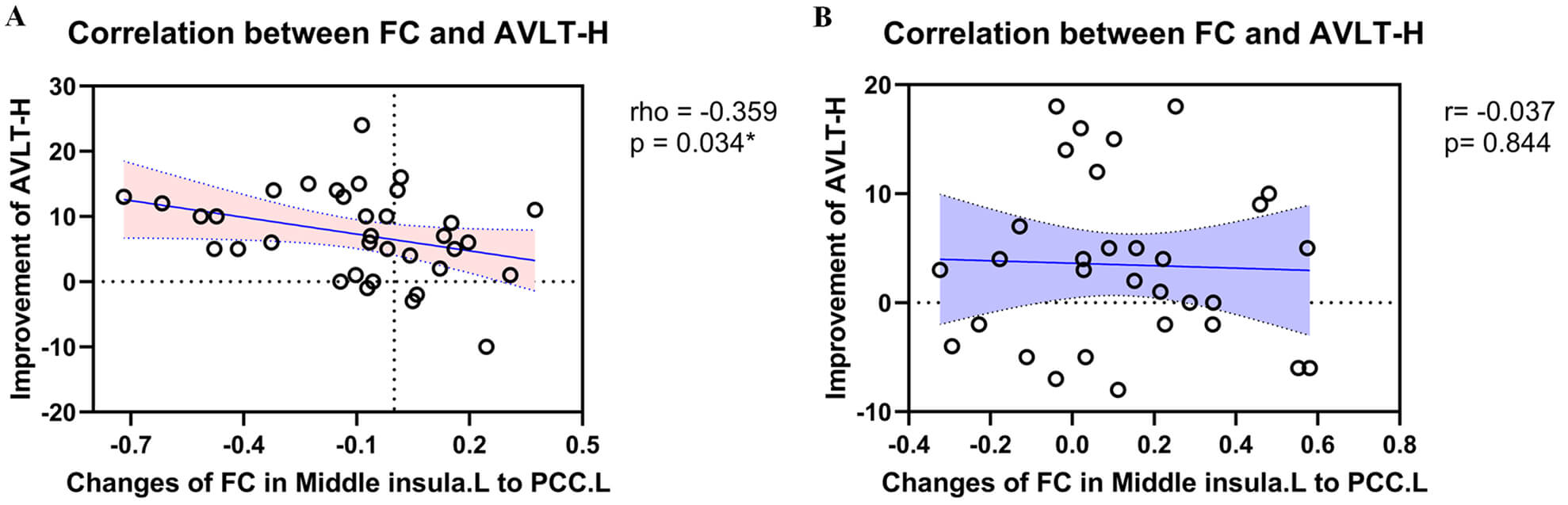

Correlation analysis of clinical variables and FCs with a significant interaction effect indicated that changes in functional connectivity between the middle insular and left PCC in the AG were negatively related to the AVLT alterations (Spearman’s rho = –0.359; p = 0.034; Fig. 3A). In contrast, no significant correlation was found in the SG (Pearson’s r = –0.037; p = 0.844; Fig. 3B). No significant correlation was found between the changes in topological properties and the improvement in participants’ AVLT performance.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Correlation between brain network functional connectivity

changes and memory alterations. (A) Change in functional connectivity between

the middle insular and post cingulate cortex was negatively related to the

improvement of AVLT after acupuncture treatment. (B) There was no correlation

between the changes in functional connectivity in the middle insular and post

cingulate cortex and the improvements in AVLT after sham acupuncture treatment.

* p

Our secondary analysis investigated the FCs and topological reorganization of large-scale brain networks after 12 weeks of acupuncture treatment in individuals with SCD. First, the benefit of acupuncture treatment on AVLT-H total scores was identified. For brain network properties, compared with the SG, acupuncture treatment significantly modulated five FCs within and between the SMN and the CON in individuals with SCD. Additionally, enhanced nodal efficiency of the left parietal lobe and decreased betweenness degree of the right parietal lobe, which belongs to the SMN, were observed according to graph-theoretical analysis. Furthermore, the correlation between functional connectivity changes in the left middle insular and left PCC and improvements in AVLT-H was significant. These findings shed light on how acupuncture improves the memory of individuals with SCD by modulating large-scale resting-state brain network properties.

We found that the AVLT-H total scores in individuals with SCD showed a

significant group

Shreds of evidence have indicated that a mutual influence exists between the subjective cognition complaint and the objective cognitive function. SCD may reflect concurrent objective impairment, which in turn influences subjective complaints [23, 33]. A recent longitudinal systematic review found that SCD patients exhibited poorer overall cognitive and objective memory performance compared with non-individuals with SCD [34]. Better objective memory performance in individuals with SCD is associated with fewer subjective complaints [23]. Objective memory impairment in individuals with SCD suggests possible Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [23]. Our study indicated that acupuncture could improve objective memory, potentially offering a new intervention strategy against dementia progression in SCD patients.

Regarding brain network properties, two positive FCs within the SMN were

increased by acupuncture, with a significant group

The CON, one of the executive control networks [39], is closely related to cognitive complaints, especially in the executive, attention, and episodic memory domains [40]. Greater intrinsic FCs in the CON have been associated with better episodic memory [41]. Decreased inter-network FCs, combined with increased within-network FCs, suggest the successful functional segregation of the SMN and the CON after acupuncture treatment. The decline in brain network FCs associated with cognitive impairment has previously been shown to predominantly occur between the DMN and the executive control networks (including the CON) [42]. The correlation between the DMN and executive control networks significantly increases with task intensity, especially during working-memory tasks [43]. However, there has been relatively little research examining the relationship between FCs between the SMN and CON and cognitive decline. Our findings fill this gap and show that acupuncture may modulate functional connections between the CON and SMN networks in individuals with SCD, thereby improving cognitive function.

Decreased SMN-CON connectivity is significantly associated with improvements in objective memory. Specifically, a decrease in the middle insular cortex-PCC connectivity negatively correlates with an improvement in AVLT-H scores. The insula is one of the most susceptible regions to SCD and a critical integration hub in human brain networks [37, 44]. Alterations in FCs between insular subregions and regions of the executive control network are essential to the neural mechanisms underlying cognitive decline in SCD [37]. Notably, the left posterior insula shows significant negative connectivity with the PCC in healthy older adults [37]. Our results suggest that acupuncture may improve objective memory in SCD by enhancing negative connectivity of the middle and posterior insula, which are both considered to be components of the SMN [26, 45].

The enhancement of negative connectivity signifies functional segregation and

mutual inhibition between brain regions, as activation in one region diminishes

activity in another [46]. Research has shown that both the insula and the PCC

support memory encoding and retrieval [47]. A common pattern of deactivation has

been observed in the PCC during attentionally demanding tasks [48], whereas the

insula is significantly activated in human-face- or tactile-recognition-memory

tests [49]. Hence, negative insula-PCC functional connectivity enhanced by

acupuncture may indicate successful segregation or inhibition between the insula

and the PCC, thus prompting memory consolidation and attention in individuals

with SCD. Our findings suggest different regulatory directions of acupuncture and

sham-acupuncture in the middle insula-PCC functional connectivity. Although

significant group differences remained after controlling for baseline values (F =

8.227, p = 0.006, Partial

Our study has some limitations. First, the p values reported were obtained using 5000 random sampling tests (without correction); validation is required in future studies that include more samples, which will provide greater statistical power. Second, our study also found that changes in FCs between brain regions associated with emotions, such as the insular cortex and the PCC, showed an interaction effect after the intervention. Since previous research has suggested that older adults with emotional burdens are more likely to perceive cognitive decline [17], future research could delve deeper into the relationship between emotions and cognition in SCD. Third, we focused primarily on the large-scale brain networks related to memory function in this study. The cerebellum potentially contributes to language, attention, and episodic memory encoding; the exact mechanisms by which the cerebellum contributes to these cognitive processes need further elucidation.

The present study investigated the brain network basis of acupuncture in improving memory. Acupuncture intervention (12 weeks) enhanced objective memory performance in individuals with SCD by reducing FCs between the SMN and CON and modulating SMN network topology, enhancing the functional segregation of these networks as potential targets for acupuncture treatment.

fMRI, functional magnetic resonance imaging; TR, Repitation Time; TE, Echo Time; FWHM, full width at half maxima; ROI, regions of interest; MNI, Montreal Neurological Institute; AUC, area under the curve; SMN, sensorimotor network; CON, cingulo-opercular network; AVLT-H, Auditory Verbal Learning Test-Huashan version; SG, sham acupuncture group; AG, acupuncture group; SE, standard error of the mean; FC, Functional connectivity; vFC, ventral frontal cortex; PCC, post cingulate cortex; L, left; R, right.

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Study concept and design: CZL, XW, CQY, GXS, LW. Acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data: XW, HZ, XYW, CKL, ZYW, CQY. Drafting of the manuscript: HZ, LW, GXS, XW. Revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content: CZL, XW, HZ, GXS, LW, XYW, CKL, ZYW. Statistical analysis: XW, HZ. Study supervision: GXS, XW. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The research protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the Beijing Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine affiliated with Capital Medical University (Ethic Approval Number: 2017BL-061-03), and all of the participants provided signed informed consent.

We gratefully acknowledge the Beijing Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital of Capital Medical University for the assistance and guidance provided during the research implementation process.

This work was partially funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81674055) and the National High-Level Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital Clinical Research Funding (DZMG-QNHB0006, DZMG-QNZX-24002).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/JIN45003.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.