1 School of Automation, Qingdao University, 266073 Qingdao, Shandong, China

2 Department of Pharmacology, School of Pharmacy, Qingdao University, 266073 Qingdao, Shandong, China

Abstract

This study addressed three key challenges in subject-independent electroencephalography (EEG) emotion recognition: limited data availability, restricted cross-domain knowledge transfer, and suboptimal feature extraction. The aim is to develop an innovative framework that enhances recognition performance while preserving data privacy.

This study introduces a novel multi-teacher knowledge distillation framework that incorporates data privacy considerations. The framework first comprises n subnets, each sequentially trained on distinct EEG datasets without data sharing. The subnets, excluding the initial one, acquire knowledge through the weights and features of all preceding subnets, enabling access to more EEG signals during the training process while maintaining privacy. To enhance cross-domain knowledge transfer, a multi-teacher knowledge distillation strategy was designed, featuring knowledge filters and adaptive multi-teacher knowledge distillation losses. The knowledge filter integrates cross-domain information using a multi-head attention module with a gate mechanism, ensuring effective inheritance of knowledge from all previous subnets. Simultaneously, the adaptive multi-teacher knowledge distillation loss dynamically adjusts the direction of knowledge transfer based on filtered feature similarity, preventing knowledge loss in single-teacher models. Furthermore, a spatio-temporal gate module is proposed to eliminate unnecessary frame-level information from different channels and extract important channels for improved feature representation without requiring expert knowledge.

Experimental results demonstrate the superiority of the proposed method over the current state of the art, achieving a 2% performance improvement on the DEAP dataset.

The proposed multi-teacher distillation framework with data privacy addresses the challenges of insufficient data availability, limited cross-domain knowledge transfer, and suboptimal feature extraction in subject-independent EEG emotion recognition, demonstrating strong potential for scalable and privacy-preserving emotion recognition applications.

Keywords

- electroencephalography

- emotions

- data privacy

- machine learning

In recent years, there has been extensive exploration of biological signals to uncover potential relationships between the nervous system and physiological functions in humans [1, 2, 3]. This investigation has revealed new avenues in fields such as disease monitoring [4], exercise therapy [5, 6], and exercise rehabilitation [7, 8]. In the realm of implantable signal processing, electromyography (EMG) signals have successfully controlled bionic hands for amputees [9], demonstrating remarkable success. However, the implantable signal collection mode, which entails open wounds, presents hazards, rendering the non-invasive mode a safer alternative. Electroencephalography (EEG) signals, as a standard non-invasive neural signal, have garnered considerable interest due to their robust temporal resolution and resistance to interference [10]. EEG emotion recognition [11, 12], in particular, has emerged as a valuable method for detecting fear and anxiety disorders, contributing to the improvement of mental health. Meanwhile, some publicly available EEG emotion datasets, including SEED (https://bcmi.sjtu.edu.cn/home/seed/) [13], DEAP (http://www.eecs.qmul.ac.uk/mmv/datasets/deap/) [14] and DREAMER (https://zenodo.org/record/546113) [15], have also provided a foundation and guarantee for the rapid development of this field.

Currently, artificial intelligence (AI)-based approaches, encompassing both traditional machine learning techniques and deep learning (DL) methods [16, 17], have become the predominant paradigm in EEG-based emotion recognition. Approaches such as Support Vector Machines (SVM) [18], Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) [19], and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) [20] have achieved notable success, contributing to substantial improvements in overall performance. However, most of these methods operate in a subject-dependent mode, which restricts their generalizability and practical applicability. In contrast, the subject-independent mode offers broader application prospects, but faces three main challenges in EEG emotion recognition: (1) insufficient available data [21]: large volume of cross-subject data is essential for model training; otherwise, it becomes challenging to capture subject-invariant features [22]; however, EEG signals, due to their sensitive and privacy-preserving nature, are difficult to collect in large quantities, which hinders performance improvement in subject-independent settings; (2) insufficient cross-domain knowledge transfer [23]: the EEG signals of different subjects are from different domains; obtaining universal knowledge from a portion of subjects and achieving cross-domain knowledge transfer to complete the EEG emotion recognition from other subjects are significantly important [24, 25, 26]; however, the current limited performance of cross-domain knowledge transfer cannot further optimize recognition precision; (3) insufficient feature extraction: most EEG signal feature extraction methods, such as differential entropy [27], asymmetric spatial pattern [28], and high order zero crossing count [29] rely on manual design, which requires high professional knowledge from researchers and can sometimes cause information loss; besides, existing automatic feature extraction methods generally focus on spatial information extraction [30], ignoring the screening of time segments, which leads to a large amount of unnecessary information interfering with the recognition results.

In response to the above issues, this paper designs the framework from three corresponding aspects. First, to obtain more data for model training, the paper proposes a multi-teacher knowledge distillation (KD) framework, which includes n subnets under serial mode. All subnets, except the initial one, are trained sequentially on distinct EEG datasets, incorporating feature representations from all previously trained subnets to consolidate accumulated knowledge and facilitate cross-domain knowledge transfer [31]. During this process, each subnet relies solely on the pretrained weights of preceding subnets without sharing raw EEG data, thereby preserving data privacy [32] while enhancing performance in EEG-based emotion recognition.

Second, to enhance cross-domain knowledge transfer, the study introduces a knowledge filter (KF) and an adaptive multi-teacher KDloss. The KF integrates features from multiple domains using a gated multi-head attention mechanism, selectively inheriting knowledge relevant to the current domain and thereby improving cross-domain knowledge transfer. Meanwhile, the adaptive multi-teacher KDloss adaptively regulates the direction of knowledge transfer by evaluating feature similarities across all preceding subnets, mitigating potential knowledge loss associated with reliance on a single teacher model.

Third, to improve the effectiveness of automatic feature extraction, the study proposes a spatio-temporal gate (STG) module to handle varying reaction periods of the same emotion across different EEG electrodes. The module identifies salient frame-level segments for each channel by computing similarities between frames and applying a sigmoid function, and subsequently adjusts channel-wise weights through self-attention to optimize frame-level representations. This feature extraction process aligns with the characteristics of EEG signals, effectively filtering out irrelevant information.

A multi-teacher knowledge distillation framework with data privacy (MTKDDP) is suggested for EEG emotion recognition. The framework employs adaptive knowledge distillation, feature filtering, and spatiotemporal gating to tackle challenges related to limited cross-domain knowledge transfer, inadequate data, and suboptimal feature extraction, thereby enhancing generalization, robustness, and automatic feature learning in subject-independent contexts. Experimental results demonstrate a 2% enhancement in performance compared to current methodologies on the DEAP dataset.

KD [33] has emerged as a crucial technique for model compression and transfer learning. By leveraging a loss function that incorporates both soft and hard targets, KD enables the effective transfer of knowledge from a teacher network to a student network. As a widely adopted approach, it facilitates transferring knowledge from one or multiple large teacher models to a more compact student model [33, 34]. However, conventional KD approaches generally depend on a single teacher network, which limits knowledge diversity and fails to effectively address cross-domain variability in EEG emotion recognition [23, 26]. To overcome this limitation, multi-teacher knowledge distillation (MTKD) has been introduced, allowing a student model to learn from multiple teachers and thereby enhancing the diversity and robustness of knowledge transfer [35, 36, 37, 38]. For example, Ye et al. [39] propose a multi-teacher feature-ensemble strategy that aggregates representations from multiple teachers to enhance transfer effectiveness. Nevertheless, many existing MTKD methods aggregate teacher outputs using simple averaging or other static rules, which can degrade performance when teacher predictions are of low quality [40, 41]. Despite these advances, MTKD still faces limitations in facilitating cross-domain knowledge transfer, as naive feature aggregation may result in information loss and fail to fully capture heterogeneous domain knowledge. To address this issue, this paper proposes an MTKD method that combines KF with an adaptive multi-teacher KDloss, selectively integrating complementary cross-domain information while minimizing redundancy and noise, thereby improving generalization and robustness in subject-independent EEG emotion recognition.

AI-based technologies for EEG emotion recognition achieve significant progress, encompassing both traditional machine learning and DL approaches. Early methods, such as SVM and K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), demonstrate feasibility but depend on manual feature engineering and struggle to scale effectively to high-dimensional EEG data [42, 43]. Subsequent variants like the Universal Support Vector Machine (USVM) aim to reduce complexity yet still show generalization limitations [44]. DL frameworks emerge as powerful alternatives, learning complex representations directly from EEG signals. For instance, regional-asymmetric convolution enhances fine-grained pattern capture, while generative modeling supports improved training efficiency [30, 45]. Despite these advances, the subject-independent setting continues to face inadequate data availability. Robust, generalizable features require large and diverse datasets, which remain difficult to obtain in practice [11, 13]. Data augmentation and transfer learning provide partial alleviation but frequently require cross-subject or cross-institutional sharing of raw EEG data, thereby introducing privacy and compliance concerns [16, 17, 46]. KD addresses these concerns by enabling knowledge transfer without exposing raw data [32]; nevertheless, most KD approaches in EEG emotion recognition rely on single-teacher frameworks, constraining knowledge diversity and limiting robustness under conditions of data scarcity [47, 48]. Recent work on multi-teacher KD introduces adaptive teacher selection and weighting to improve stability and transfer quality, although its application to EEG emotion recognition remains underexplored [36, 39].

Beyond data limitations, inadequate feature extraction constitutes a second major bottleneck. EEG signals exhibit rich spatiotemporal dynamics, necessitating models that capture spatial–temporal dependencies while effectively suppressing noise. Handcrafted features, such as differential entropy and asymmetric spatial patterns, provide partial solutions but remain susceptible to information loss and rely heavily on expert design [27, 28]. DL models improve automatic representation learning, yet many lack dynamic mechanisms to filter redundant or irrelevant frame-level segments. For instance, models designed to learn spatiotemporal dependencies may still omit adaptive cross-channel gating, leading to residual noise and reduced accuracy [49]. Addressing these gaps requires frameworks that simultaneously extract fine-grained spatiotemporal representations and perform dynamic filtering. To this end, the proposed MTKDDP framework sequentially trains multiple subnets on heterogeneous EEG datasets without sharing raw data and distills complementary knowledge from multiple teachers to enhance generalization under conditions of limited data [36, 39]. In parallel, a STG module adaptively selects salient frame-level features across channels using attention-based similarity, thereby reducing redundancy and strengthening representation quality [50]. In combination, knowledge filtering and adaptive distillation loss further improve cross-domain generalization while maintaining privacy protection.

Here, a comprehensive overview is presented for the four components of the MTKDDP framework, including EEG signal preprocessing, the MTKDDP architecture, the STG module and the MTKDDP algorithm.

The original EEG signals are commonly represented as multi-dimensional tensors with baseline signals. Since neural networks generally require matrix-like input, these tensors do not directly satisfy this requirement. Consequently, preprocessing is necessary to reshape EEG signals into suitable dimensions for network input. Based on the design of the STG module in the paper, the original EEG signal is processed into a signal of size (C, T, N) without the baseline signals, where C represents the number of channels, T is the number of time steps, and N indicates the number of samples. The detailed preprocessing steps are as follows:

First, the baseline in the original EEG signals is removed using signals recorded in a calm state. Specifically, the per-second mean of the calm-state signals is computed as the baseline, which is then subtracted from the emotional signals to complete the preprocessing. Second, similar to Wang’s method [48], the processed signal is divided into multiple frame-level signals according to the 3 seconds per segment [50]. Here, the length of each frame level signal is defined as 3 seconds to ensure sufficient emotional information and avoid excessive redundant information. Therefore, if the total length of the original signal is T𝑠𝑢𝑚, then T = T𝑠𝑢𝑚 /3 and the size of the signal is (T, C, N). Afterwards, the existing signals are transposed as the signal of size (C, T, N), which meets the input requirements of our framework. Additionally, to reduce model complexity, downsampling is applied, proportionally scaling the data with respect to N to improve computational efficiency.

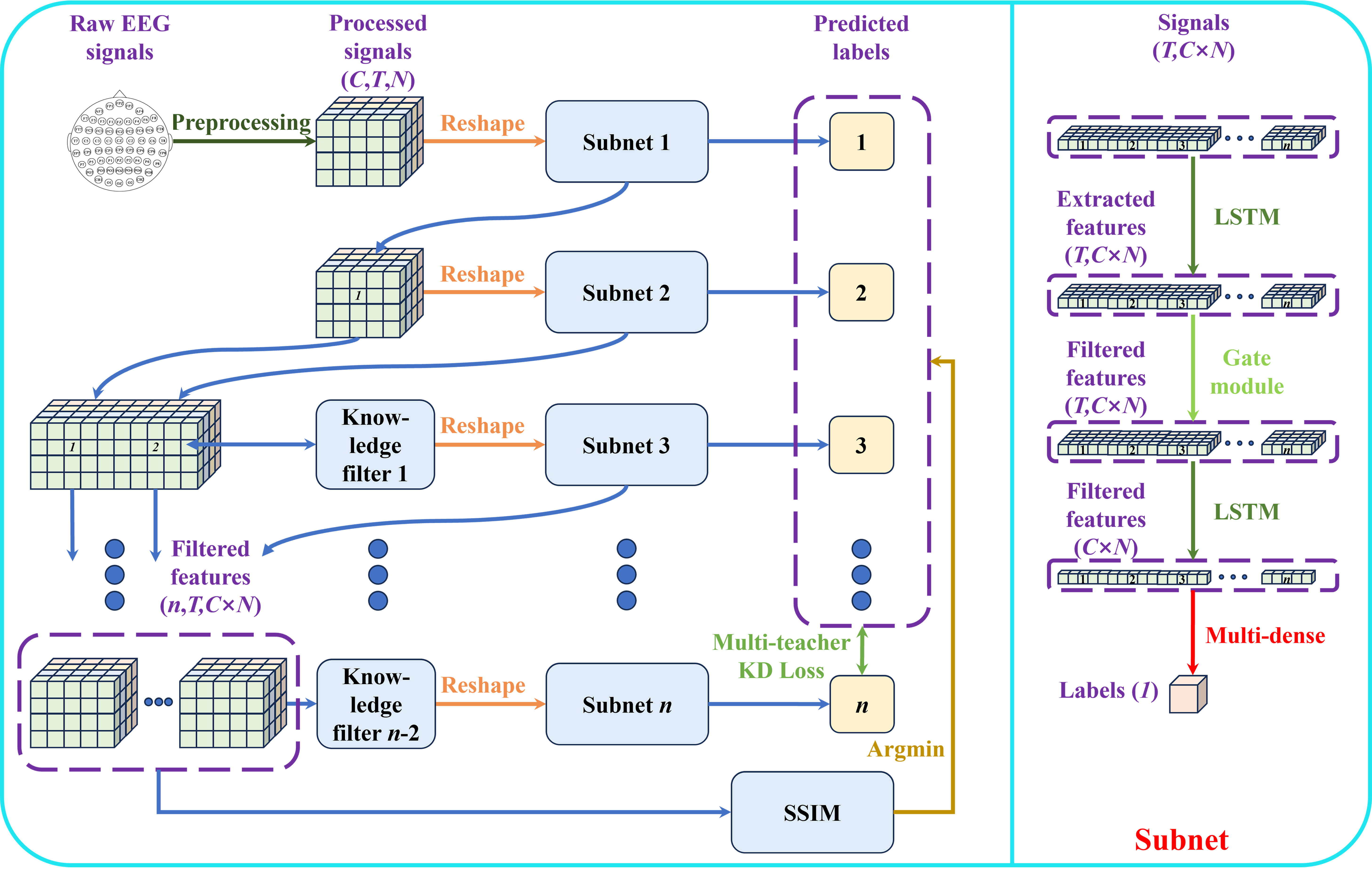

To optimize performance in subject-independent EEG emotion recognition, this work proposes a multi-teacher KD framework that preserves data privacy [46, 51, 52], as shown in Fig. 1, for enhancing knowledge transfer and automatic feature extraction. The framework includes n subnets and (n-2) KFs, which are detailed in the subsequent subsection. Except for the initial subnet, each subnet contains only 1.3 M parameters, demonstrating the framework’s efficiency. The framework is optimized by sequentially training subnets on different EEG signals to ensure privacy protection. Each subnet comprises two LSTM layers, a gate module, and a multi-dense module. The first LSTM layer extracts temporal features, while the second LSTM layer maps these features to labels. The gate module, positioned between the two LSTM layers and detailed in the following subsection, selectively eliminates unnecessary features. Finally, the multi-dense module, located at the end, performs label prediction. Especially, the first LSTM layer and gate module of the first subnet are different from the subsequent subnets, where the first LSTM layer in the first subnet is trained by EEG signals of single channel together to obtain feature information. The first gate module is the STG module, which screens emotional response periods across different electrode positions and removes irrelevant information, while subsequent gate modules operate based on temporal features. During training, the weights of each trained subnet are frozen, and only the filtered features are provided as input to the following subnet to enhance knowledge transfer. When more than two subnets are employed, the KF selects features generated by all preceding subnets to ensure the effectiveness of knowledge transfer. In addition, except for the first LSTM layer of each subnet using ReLU activation function and the output layer using Sigmoid activation function, all other activation functions are Tanh.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The architecture of our MTKDDP for EEG emotion recognition. MTKDDP, multi-teacher knowledge distillation framework with data privacy; EEG, electroencephalography; KD, knowledge distillation; SSIM, Structural Similarity; LSTM, Long Short-Term Memory.

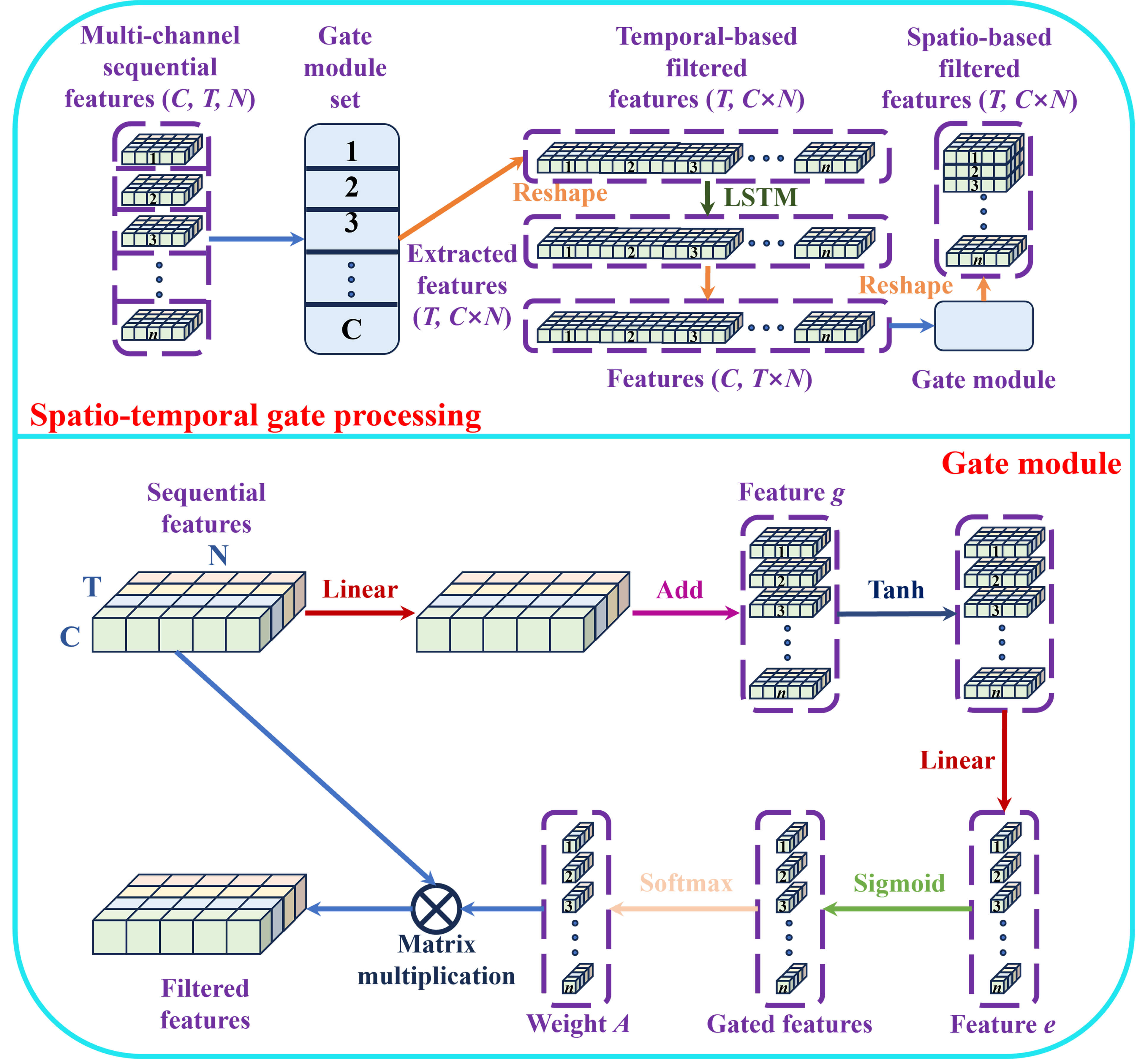

Capturing emotional information across the entire EEG signal presents

challenges, as the response times at different electrode positions are often

inconsistent. To overcome the limitations of existing feature extraction methods

that focus solely on spatial information, this work introduces the STG module,

illustrated in Fig. 2, which extracts the most relevant features between

electrode positions and emotional responses. The STG module effectively filters

out unnecessary features from each electrode, thereby enhancing automatic feature

extraction. The module comprises three components: a temporal-based gate module

set, an LSTM layer, and a spatio-based gate module. In the temporal-based gate

module set, gate modules are utilized to filter features C times, with

shared weights optimizing the temporal-based gate modules more effectively.

Subsequently, after adjusting the feature size, features with dimensions

(T, C

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

The details of spatio-temporal gate module.

Assuming the input of the gate module is H =

where Wg, Wg′ and We are the weights of the

linear layer, bg and be indicate the bias of the

linear layer, t and t′ represent the time steps, and

The

Hence, the weight matrix AT*T for filtering features is calculated. Then, the paper can get the filtered feature O as follows:

Here, the STG module can be used to usefully filter the unnecessary features by Eqns. 1,2,3,4. In addition, all subnets except the first employ gate units as gate modules to enhance feature extraction.

EEG signals involve personal privacy and are challenging to collect publicly in large quantities, which limits the optimization of models for EEG emotion recognition. In particular, in the subject-independent mode, cross-domain knowledge transfer remains insufficient. Therefore, the paper proposes a multi-teacher KD framework with data privacy, which includes n subnets trained sequentially. The framework enables knowledge transfer to enhance performance without sharing EEG signals, while leveraging multi-teacher KD to facilitate cross-domain knowledge transfer, using the adaptive multi-teacher KDloss to guide the direction of knowledge transfer. The training process is divided into three stages.

First, the preprocessed EEG signals are utilized to train the initial subnet, wherein the network’s output is aligned directly with the ground truth distribution through the cross-entropy loss function, expressed as follows:

where p denotes the prediction from the first subnet and q represents the ground truth.

Second, the features meticulously filtered by the initial subnet serve as inputs for the subsequent subnet. The KDloss is then applied to guide its outputs toward both the soft targets predicted by the initial subnet and the hard targets derived from the actual labels. This intricate process achieves effective knowledge transfer and successfully concludes the model training phase. The KDloss is represented as follows:

where z indicates the prediction from the second subnet before the last

Sigmoid function, T* indicates the temperature, and

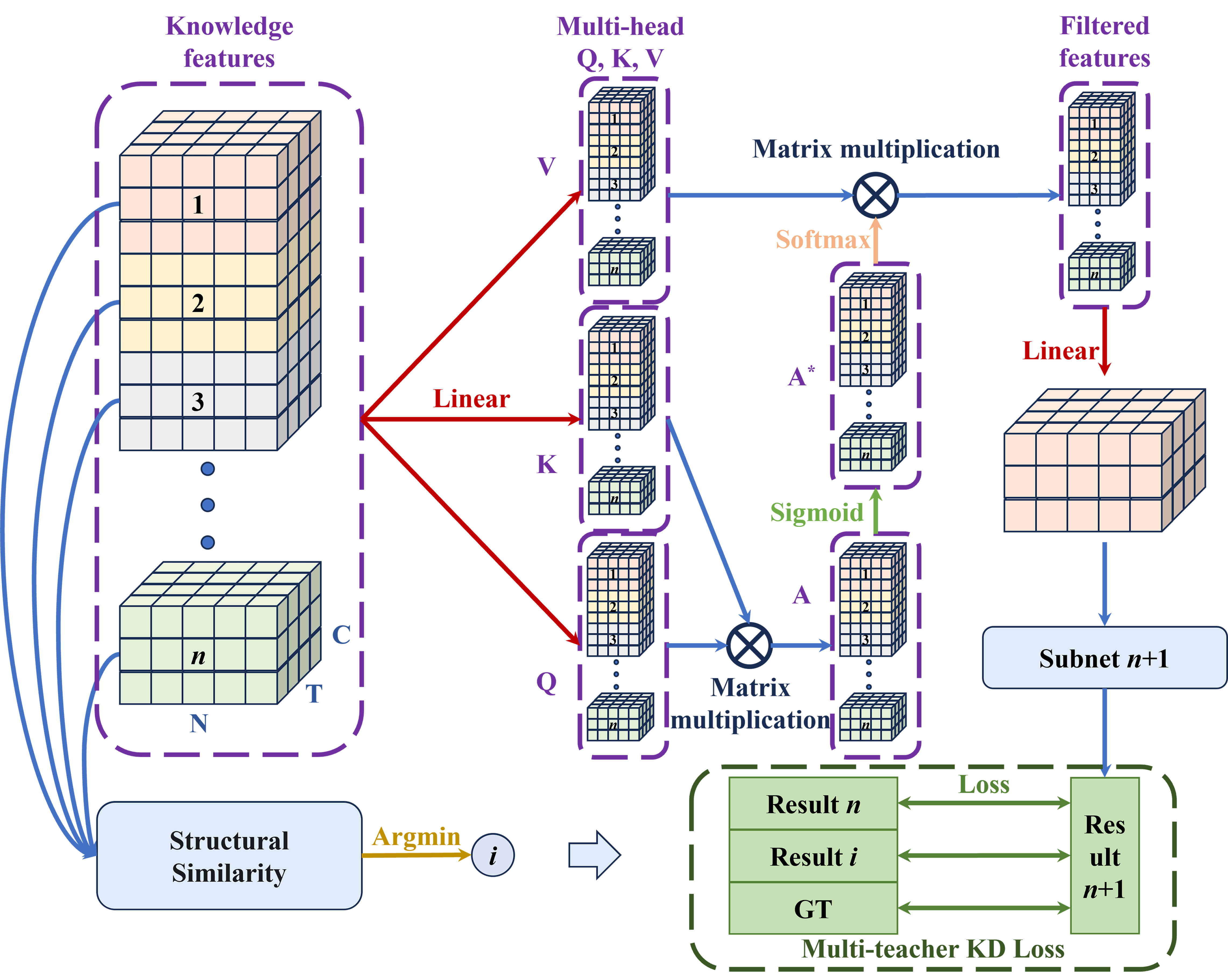

Third, the multi-teacher knowledge KD strategy is employed to train the

n-th subnet (n

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

The details of multi-teacher knowledge distillation strategy. GT, ground truth.

The adaptive loss is defined as follows:

where k indicates the ratio between the direction of two soft targets. z, p 1 and p 2 represent the prediction from (n+1)-th subnet, n-th subnet and i-th subnet respectively.

Here, to retain maximum knowledge, the subnet exhibiting the lowest similarity between the output and feature O𝑛 is employed as an additional teacher network to optimize the current subnet. Thus, i is solved as follows:

During the training process, k can adjust the balance between the training cost and the final performance. As k increases, the subnet mainly inherits the knowledge of its previous subnet, where the model can converge quickly with weak generalization performance. In contrast, the model achieves improved generalization performance, although convergence is slow. Increasing the number of subnets can enhance both performance and generalization, but this incurs substantial computational cost. To address this issue, a pruning method is employed, in which the model is pruned and training is halted once the feature similarity of three consecutive subnets exceeds a predefined threshold.

This section presents the implementation details used to demonstrate the performance of the framework. Then, the performance of the MTKDDP framework is analyzed through comparative experiments on the public DEAP dataset [14] and DREAMER dataset [15] in subject-independent mode. Subsequently, the effectiveness of the proposed methods is evaluated sequentially through ablation experiments and visualization analyses.

In comparative experiments, the selected frameworks include classical models such as Convolutional Long Short-Term Memory (CLSTM) [54] and Attention-LSTM [55], as well as state-of-the-art frameworks including Recurrent Attention Convolutional Neural Network (RACNN) [30], Attention-based Temporal Dense Dual (ATDD)-LSTM [56], Frame-Level Teacher-Student Learning With Data Privacy (FLTSDP) [47], Frame-Level Distilling Neural Network (FLDnet) [48], Cascaded Gated Recurrent Unit-Multi-Channel Dynamic Graph Network (CGRU-MDGN) [42], and Multi-Task Learning Fusion Network (MTLFuseNet) [57]. A dual strategy is employed for selecting comparison algorithms, incorporating both classical and state-of-the-art (SOTA) approaches to ensure a comprehensive and fair evaluation. Classical models such as CLSTM and Attention-LSTM serve as widely recognized baselines in EEG-based emotion recognition due to their established capability in feature extraction and temporal sequence modeling, providing reliable benchmarks for assessing the overall effectiveness of the proposed method. In addition, recent SOTA methods—including FLTSDP, which integrates data privacy protection mechanisms, as well as other advanced approaches based on knowledge distillation or transfer learning—are incorporated to evaluate performance against the latest developments in data privacy, cross-domain knowledge transfer, and feature extraction. This combination ensures that the evaluation reflects both competitiveness with established baselines and superiority in cutting-edge scenarios.

Here, the EEG signals are first preprocessed into 32

To statistically validate the differences among multiple algorithms, the

Friedman test is employed as a nonparametric approach suitable for comparing the

rankings of several models across multiple datasets or experimental conditions

[59]. This test first ranks the results of different algorithms across multiple

datasets or experimental conditions and then computes the Friedman statistic

First, to effectively demonstrate the performance of the framework, the larger DEAP dataset is employed for comparative experiments without data privacy in the subject-independent mode. Experiments utilize 5-fold cross-validation to evaluate the effectiveness and robustness of all methods. Consequently, 32 subjects are randomly divided into five groups for training and testing. The results, presented in Table 1, indicate that the framework outperforms all comparison methods across the four emotional dimensions, achieving an improvement exceeding 2%. These results further demonstrate the effectiveness of the framework in automatic feature extraction and cross-domain knowledge transfer. Compared with the FLTSDP [47] and FLDnet [48] frameworks, which also perform frame-level feature filtering, the proposed method demonstrates substantially enhanced performance. This improvement indicates that the STG module accurately captures distinct reaction times across electrode positions, thereby more effectively avoiding interference from unnecessary features. Furthermore, MTKDDP outperforms these cross-domain integrated knowledge methods in terms of overall generalization and knowledge transfer. The CGRU-MDGN proposed in Guo and Wang [49] effectively processes both the temporal dynamics and spatial features of EEG signals, including their non-Euclidean relationships, thereby enhancing the accuracy of emotion recognition. However, this model has limitations in cross-domain knowledge transfer, while MTKDDP adopts multi-teacher KD strategy to integrate knowledge of different subnets more effectively and enhance the effect of cross-domain knowledge transfer. In addition, MTLFuseNet is an emotion recognition model based on EEG deep latent feature fusion and multi-task learning [57]. MTKDDP addresses challenges such as multi-task feature interference, significant knowledge forgetting, and low computational efficiency. It employs multi-teacher hierarchical distillation to decouple task-specific features, dynamic knowledge solidification to mitigate forgetting, and combines parameter sharing with asynchronous updates to improve efficiency, thereby substantially enhancing accuracy and robustness. Furthermore, whereas conventional multi-teacher approaches often incur prohibitive computational overhead, MTKDDP achieves comparable time complexity to SOTA single-teacher frameworks through optimized parameter sharing and asynchronous gradient updates. This dual advantage of increased robustness against forgetting and preserved operational efficiency highlights the distinctive applicability of the framework in real-world scenarios.

| Prediction target | Attention-LSTM | RACNN | ATDD-LSTM | FLDNet | FLTSDP | CGRU-MDGN | MTLFuseNet | MTKDDP |

| Valence | 76.77% |

80.55% |

74.73% |

83.85% |

92.40% |

69.92% |

71.33% |

94.24% |

| Arousal | 70.71% |

74.64% |

67.44% |

78.22% |

82.51% |

70.08% |

73.28% |

92.58% |

| Dominance | 72.06% |

74.64% |

68.41% |

77.52% |

89.95% |

71.01% |

- | 93.27% |

| Liking | 76.48% |

79.30% |

75.47% |

82.42% |

91.20% |

- | - | 94.64% |

| Valence - dp | 65.31% |

80.88% |

56.62% |

- | 91.45% |

- | - | 94.89% |

| Arousal - dp | 62.67% |

67.69% |

58.94% |

- | 85.03% |

- | - | 91.92% |

| Dominance - dp | 66.07% |

69.07% |

62.22% |

- | 87.49% |

- | - | 91.90% |

| Liking - dp | 66.61% |

77.59% |

66.61% |

- | 89.14% |

- | - | 93.87% |

| Trainingtime (s/epoch) | 18.21 | 85.06 | 123.21 | 33.67 | 36.01 | - | - | 38.10 |

Note: dp indicates that only a few subjects in the training dataset are used to train with data privacy. Attention-LSTM, Attention-based Long Short-Term Memory; RACNN, Recurrent Attention Convolutional Neural Network; ATDD-LSTM, Attention-based Temporal Dense Dual-Long Short-Term Memory; FLDNet, Frame-Level Distilling Neural Network; FLTSDP, Frame-Level Teacher-Student Learning With Data Privacy; CGRU-MDGN, Cascaded Gated Recurrent Unit - Multi-Channel Dynamic Graph Network; MTLFuseNet, Multi-Task Learning Fusion Network; MTKDDP, Multi-Teacher Knowledge Distillation Framework with data privacy.

Second, to evaluate the knowledge transfer capability of the framework, comparative experiments with private data are conducted on the DEAP dataset. In these experiments, the training set under 5-fold cross-validation is divided into three groups, each containing non-overlapping EEG data from 9, 8, and 8 subjects, respectively. The results, presented in Table 1, demonstrate the optimal performance achieved by the framework. Compared with classical methods, the framework exhibits a clear performance advantage, particularly in the stability and accuracy of predictions, which also reflects the effectiveness of the privacy protection mechanisms. In comparison with the FLTSDP framework [47], which similarly incorporates privacy protection mechanisms, the superior performance of the framework highlights the contribution of the multi-teacher KD strategy in facilitating cross-domain knowledge transfer.

Third, to assess the effectiveness of the proposed modules, two types of ablation studies are conducted on the DEAP dataset. In the first type of ablation experiment, the STG module, teacher-student (TS) framework, KF module, and adaptive multi-teacher knowledge distillation loss (AMTKDL) are sequentially integrated into the base model, which corresponds to the Attention-based Long Short-Term Memory (attLSTM) model from Wang’s framework [48]. In the second type of ablation experiment, individual removal of the STG or KF modules is tested, further confirming the essential contribution of each module to feature selection and knowledge integration. The results of these ablation experiments are presented in Table 2. As shown, the proposed modules successfully enhance the performance of EEG emotion recognition, particularly the STG module, indicating its key role in eliminating unnecessary features and effectively improving overall performance. Furthermore, compared with a single network, multi-classifiers in the TS framework effectively integrate knowledge from previous subnets, enhancing network robustness. The KF module optimizes knowledge composition to further improve feature extraction, as reflected in the experimental results. Finally, the AMTKDL refines the robustness of knowledge transfer and further enhances the precision of the framework.

| Prediction target | Valence | Arousal | Dominance | Liking |

| attLSTM (A1) | 87.68% |

80.83% |

80.70% |

85.52% |

| A1+STG (A2) | 87.21% |

87.26% |

87.98% |

87.53% |

| A2+TS (A3) | 91.05% |

89.26% |

90.27% |

89.70% |

| A3+KF (A4) | 93.45% |

90.47% |

92.64% |

93.93% |

| A4+AMTKDL (A5) | 94.24% |

92.58% |

93.27% |

94.64% |

| A5-STG (A6) | 93.82% |

87.35% |

88.67% |

92.88% |

| A5-KF (A7) | 93.20% |

91.64% |

92.06% |

93.21% |

| A5+DP | 94.89% |

91.92% |

91.90% |

93.87% |

Note: attLSTM is the base model.

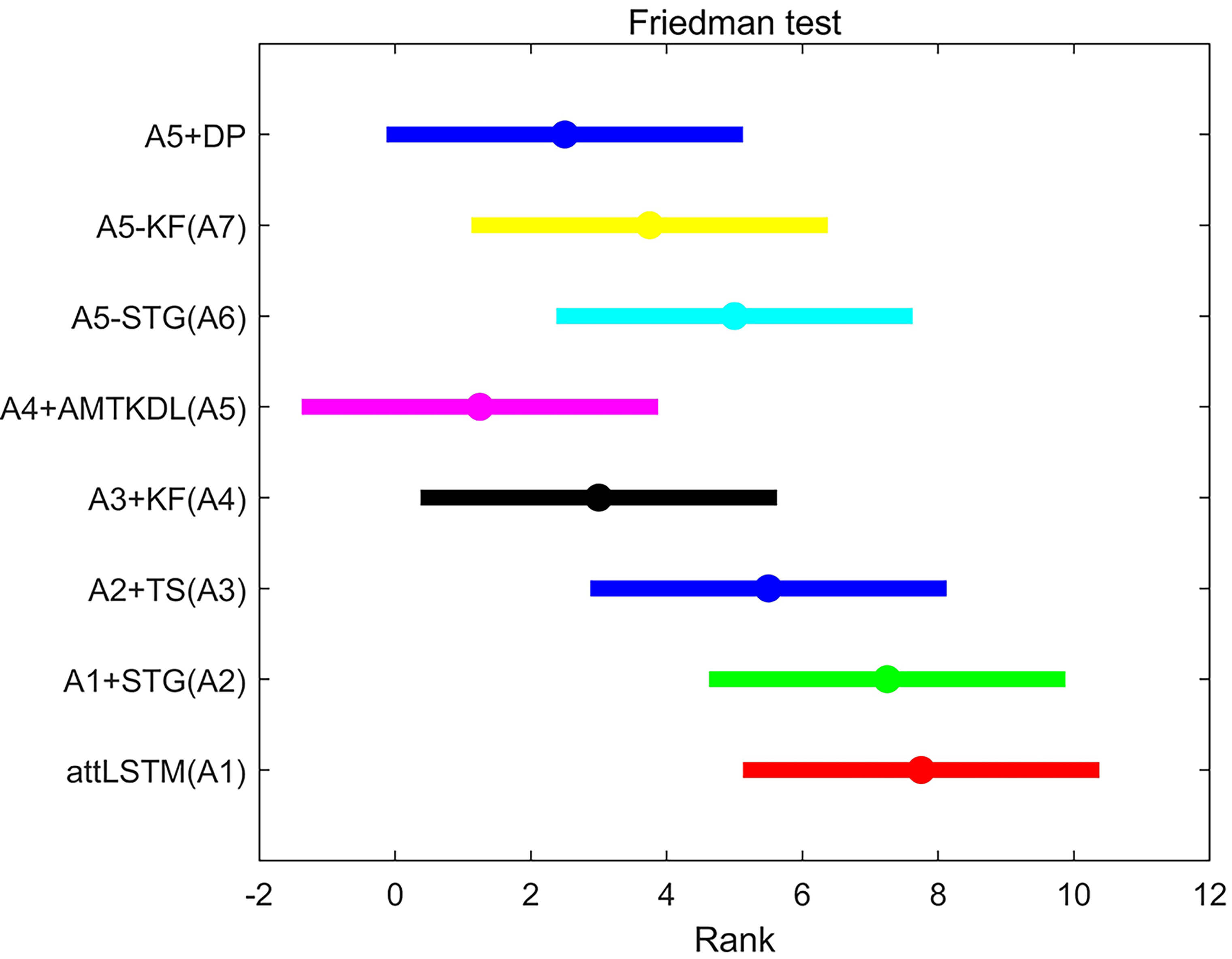

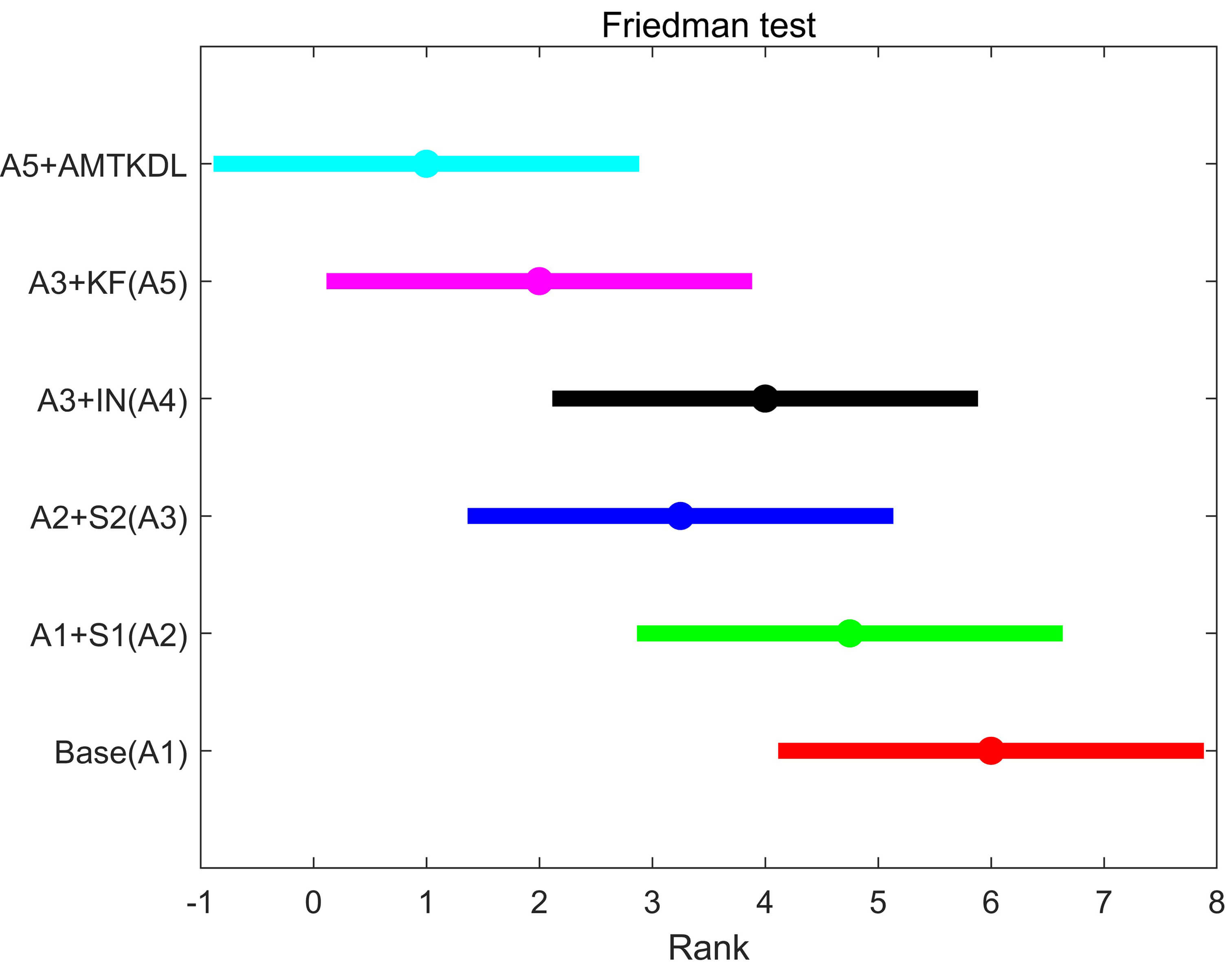

To quantitatively assess the findings from the ablation experiments, the

Friedman test is conducted, followed by the Nemenyi post-hoc test. The Friedman

statistic

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Friedman test of ablation study. DP, data privacy; KF, knowledge filter; STG, spatiotemporal gate; AMTKDL, adaptive multi-teacher knowledge distillation loss; TS, teacher-student; attLSTM, Attention-based Long Short-Term Memory.

Then, to evaluate the capability of knowledge transfer among multiple subnets,

ablation experiments on knowledge transfer methods and feature screening

visualization experiments are conducted. First, several knowledge transfer

methods—including the TS framework with Student-1 and Student-2, integrated

networks, KF, and AMTKDL—are presented in Table 3. Here, the base model

corresponds to the attLSTM model from Wang’s framework [48] with the STG module.

From the results in Table 3, the TS network clearly enhances EEG emotion

recognition; however, deeper student networks do not substantially improve

recognition accuracy. Similarly, the integrated network from FLTSDP [47] does not

further improve performance and even underperforms compared with the deeper

student networks. The KF mechanism effectively reorganizes knowledge, capturing

information more aligned with the current domain, better integrating knowledge

from previous subnets, and thereby facilitating EEG emotion recognition. To

further assess the contributions of different components in the knowledge

transfer process, the Friedman test accompanied by the Nemenyi post-hoc analysis

was conducted on the results reported in Table 3. The computed Friedman statistic

| Prediction target | Valence | Arousal | Dominance | Liking |

| Base (A1) | 87.21% |

87.26% |

87.98% |

87.53% |

| A1+S1 (A2) | 90.09% |

87.89% |

89.18% |

89.04% |

| A2+S2 (A3) | 91.05% |

89.26% |

90.27% |

89.70% |

| A3+IN (A4) | 91.08% |

88.01% |

88.98% |

89.45% |

| A3+KF (A5) | 93.45% |

90.47% |

92.64% |

93.93% |

| A5+AMTKDL | 94.24% |

92.58% |

93.27% |

94.64% |

Note: attLSTM with STG module is the base model. S1, S2, and IN are defined as student-1, student-2, and integrated network, respectively. IN, integrated networks.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Friedman test of ablation study in knowledge transfer.

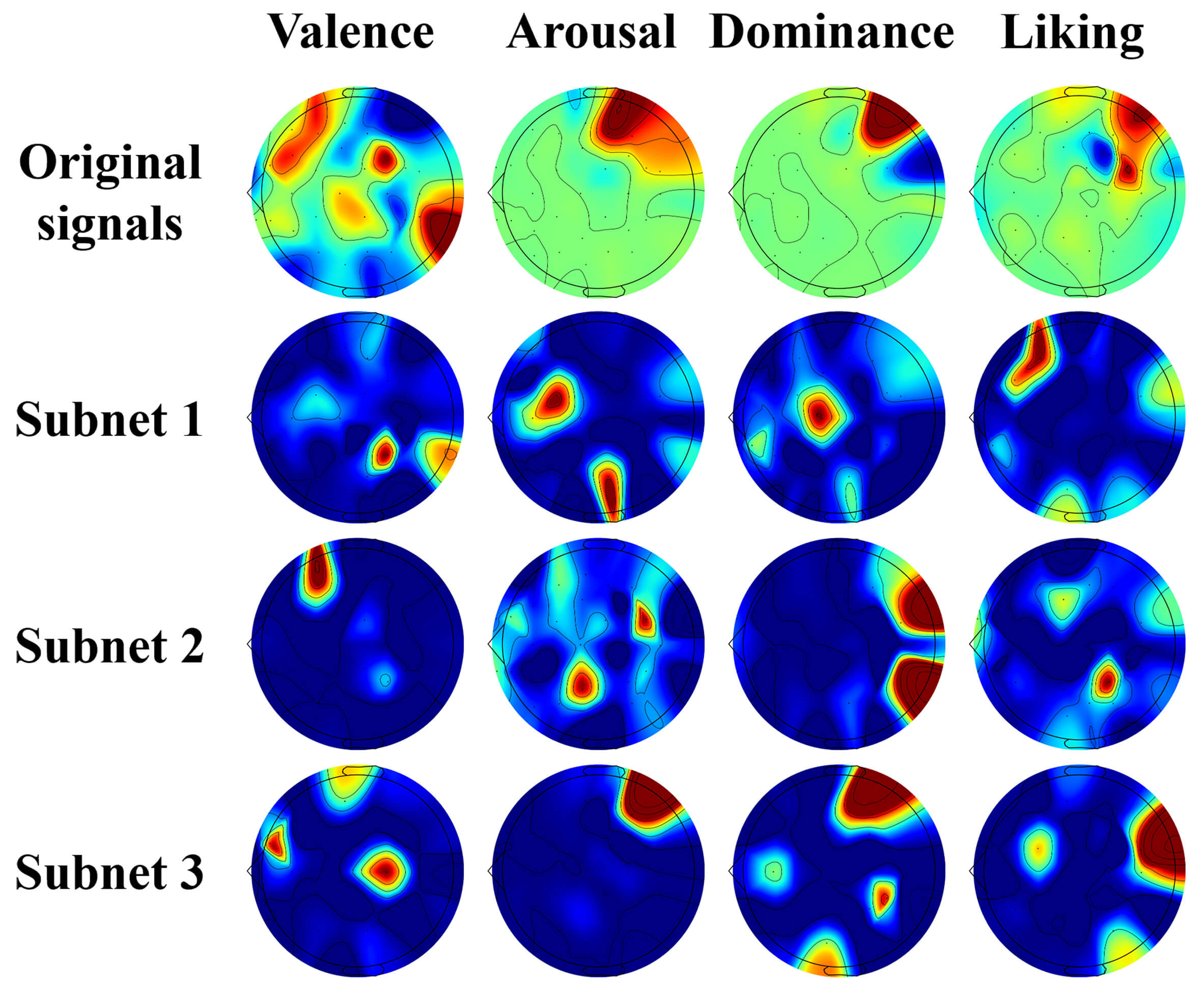

Additionally, the visualization results of the KF mechanism are presented in Fig. 6, illustrating feature extraction outcomes for the four emotional dimensions derived from EEG signals across 32 channels. The “Original signals” row visualizes raw EEG activity, with widespread red regions indicating noisy and unfocused signals with no clear alignment to emotion-specific responses. Rows corresponding to Subnet 1–3 illustrate features extracted by successive subnets. Subnet 1 shows scattered and inaccurate activation, capturing noisy or irrelevant activity. Subnet 2 displays more targeted activations, partially aligning with known emotion-related regions, but still inconsistent. By Subnet 3, activations are highly precise, with red regions sharply highlighting channels critical for each emotional dimension, as the KF module fuses outputs from previous subnets, filtering out noise and domain-irrelevant features while retaining emotion-relevant ones. This visualization demonstrates that early subnets do not fully capture target-domain emotion features; however, as subnets progress under KF guidance, features become increasingly domain-specific and accurately aligned with known neural correlates of emotion. Overall, Fig. 6 illustrates how KF and adaptive subnets collaboratively refine raw, noisy signals into precise, domain-relevant, and neurophysiologically plausible features, validating the effectiveness of adaptive knowledge transfer and the framework’s capability to enhance EEG emotion recognition.

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Visualization results of KF.

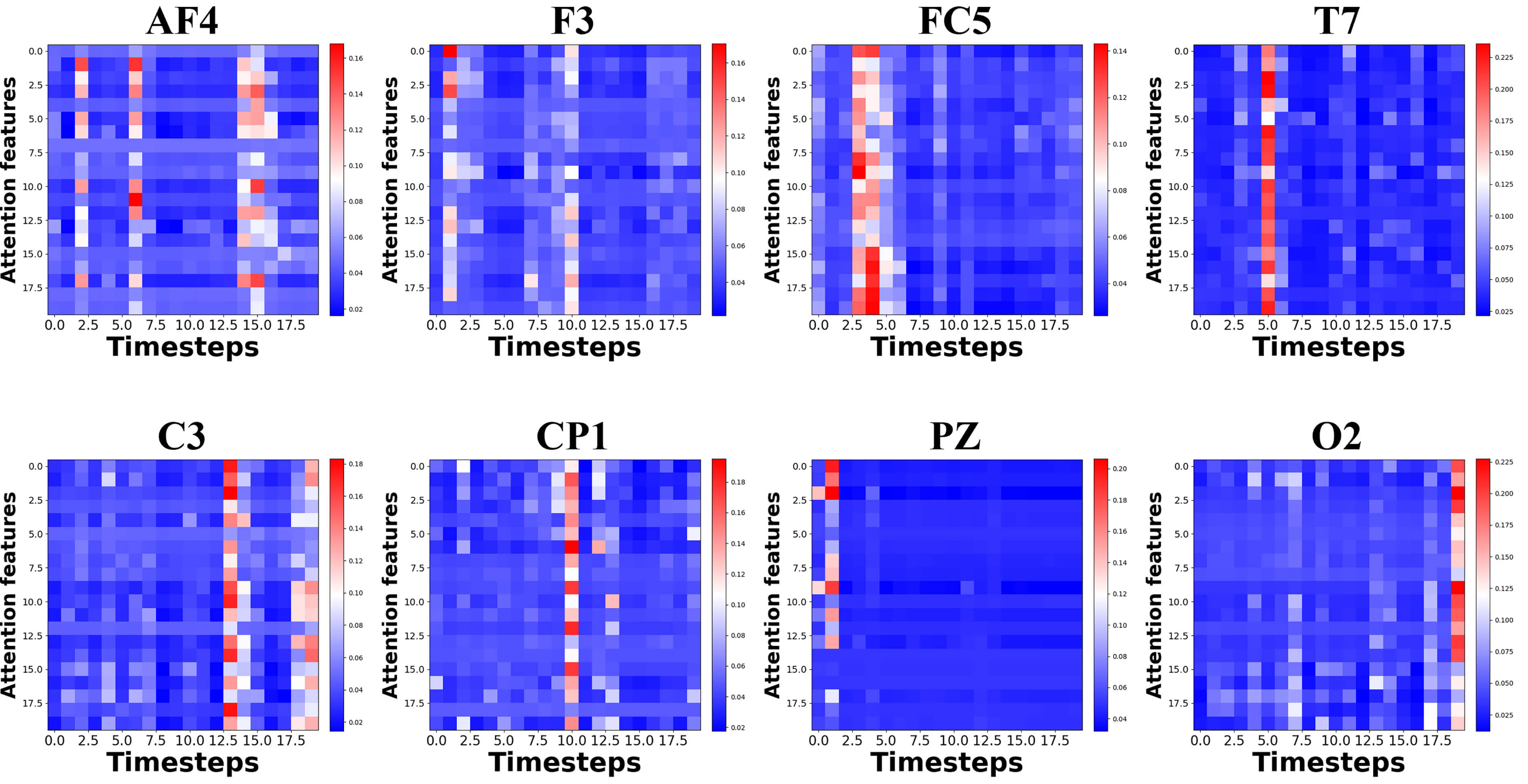

To evaluate the adaptive feature extraction capability of the STG module, temporal gate weights from multiple EEG channels are visualized, as shown in Fig. 7. The vertical axis represents electrode channels from AF4 to O2, covering frontal, central, parietal, and occipital regions, while the horizontal axis denotes 20 discrete time steps. Color intensity corresponds to gating weights, with red regions indicating higher weights. The visualization reveals that high-weight time intervals vary across channels. Frontal channels exhibit pronounced activation during early time steps, whereas central and parietal channels show sustained or delayed activation in later periods. This distribution indicates that frame-level features are both channel-specific and time-specific, with different electrodes carrying emotion-relevant information within distinct temporal windows.

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Visualization results of temporal-based gates.

The STG mechanism applies gating across both temporal and spatial dimensions. For each channel, a temporal gate assigns weights to frame-level features across time steps, followed by spatial gating that integrates contributions from all channels. This process prioritizes informative intervals and suppresses irrelevant or noisy segments, generating spatio-temporal representations optimized for emotion recognition. The strategy enhances signal quality by emphasizing high-weight intervals and reducing noise. Activation patterns in frontal and central-parietal regions align with established stages of emotional processing, improving physiological interpretability. By focusing on emotion-relevant channel-time features, the mechanism strengthens discriminative capability. Overall, the STG module functions as a spatio-temporal filter that automatically identifies critical EEG features for emotion recognition, ensuring effective and interpretable feature extraction.

To evaluate the privacy-preserving capability of the proposed framework,

differential privacy [60] is incorporated using the Differentially Private

Stochastic Gradient Descent (DP-SGD) mechanism, which limits the sensitivity of

individual samples through gradient clipping (threshold C = 1.0) and Gaussian

noise injection. During training, the privacy budget is set to

As shown in Table 4, accuracy decreases slightly as

| 0.01 | 0.001 | 0.0001 | 0.00001 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valence | 93.49% |

92.76% |

92.50% |

91.98% |

| Arousal | 89.29% |

89.00% |

88.47% |

88.34% |

| Dominance | 89.76% |

89.74% |

89.39% |

89.45% |

| Liking | 92.16% |

91.50% |

90.64% |

90.06% |

Experiments on the DREAMER dataset (Table 5) demonstrate that the MTKDDP framework consistently outperforms SOTA baselines across all three emotional dimensions. The framework achieves marked improvements over single-model approaches, illustrating the effectiveness of leveraging complementary knowledge from multiple teachers to mitigate dataset bias and enhance robustness. Reduced variability further reflects superior stability across subjects and sessions.

| Prediction target | Attention-LSTM | CLSTM | ATDD-LSTM | FLDNet | FLTSDP | RACNN | MTLFuseNet | MTKDDP |

| Valence | 83.19% |

83.72% |

86.00% |

89.91% |

91.54% |

83.69% |

80.03% |

96.61% |

| Arousal | 82.17% |

81.41% |

82.09% |

87.67% |

90.61% |

83.04% |

83.33% |

96.39% |

| Dominance | 86.67% |

85.32% |

86.37% |

90.28% |

91.00% |

83.93% |

- | 97.11% |

| Valence - dp | 81.74% |

80.66% |

85.37% |

- | 93.17% |

83.87% |

- | 96.56% |

| Arousal - dp | 81.43% |

81.13% |

82.95% |

- | 91.43% |

80.82% |

- | 96.78% |

| Dominance - dp | 84.15% |

83.17% |

83.54% |

- | 92.13% |

81.59% |

- | 97.39% |

Note: dp indicates that only a few subjects in the training dataset are used to train with data privacy. CLSTM, Convolutional LongShort Term Memory.

This strong performance stems from the synergistic integration of the STG module’s noise-invariant feature extraction and the MTKD framework’s ability to transfer robust, generalized representations. These results highlight the framework’s potential for practical EEG-based emotion recognition applications under substantial inter-subject variability and diverse recording conditions.

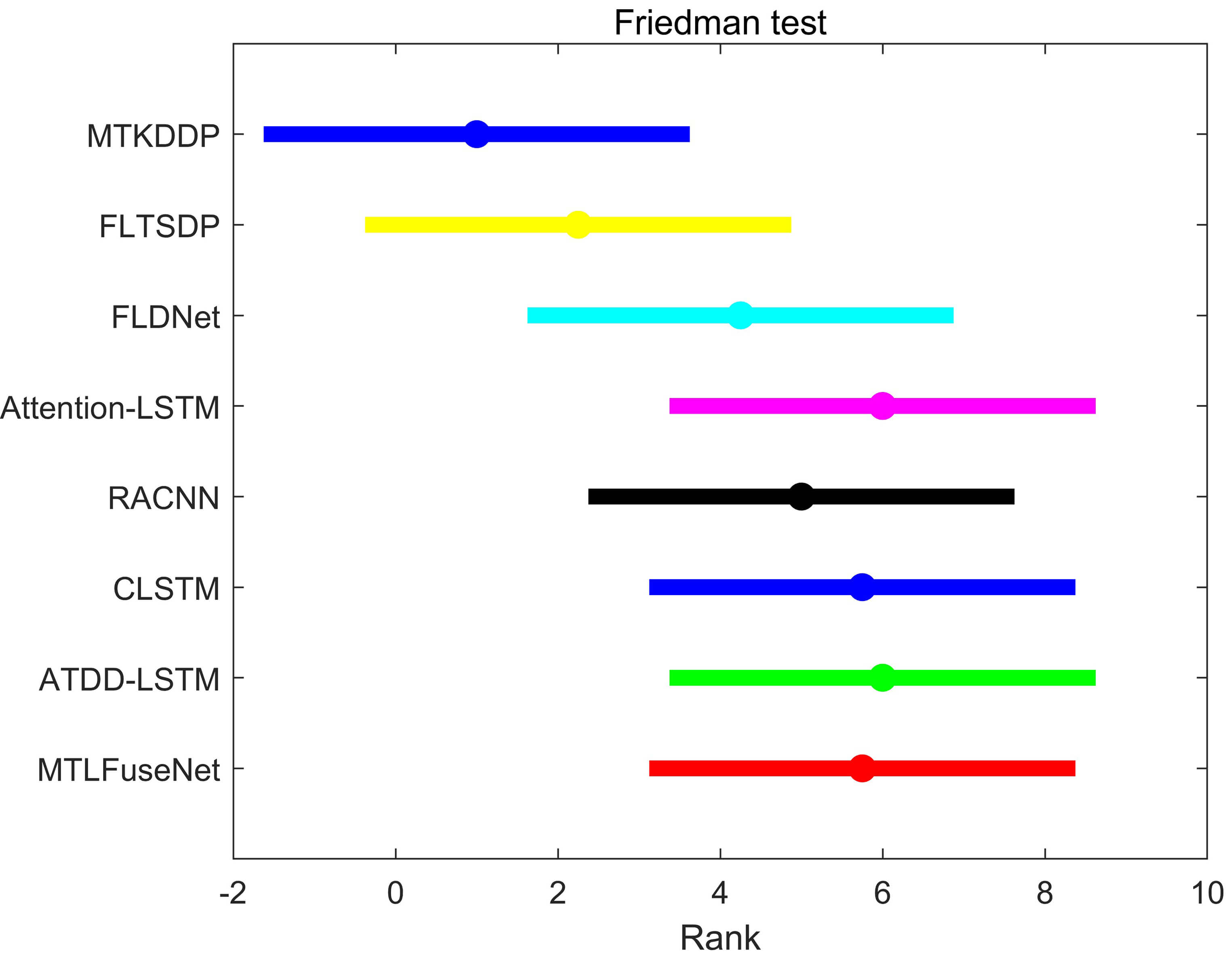

To demonstrate the superiority, effectiveness, and robustness of the proposed

MTKDDP framework, the Friedman test and Nemenyi post-hoc test were conducted. The

basic assumption of the Friedman test is that all algorithms perform equally

well. Comparisons are conducted across four publicly available EEG datasets,

involving the MTKDDP framework and seven other representative

algorithms—including Attention-LSTM, RACNN, CLSTM, ATDD-LSTM, MTLFuseNet, and

three baseline methods—comprising a total of eight algorithms. The Friedman

statistic

Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

Friedman on DEAP and DREAMER datasets.

For EEG emotion recognition in subject-independent mode, the paper proposes a multi-teacher KD framework with data privacy. The framework sequentially trains multiple subnets with different EEG signals and employs a multi-teacher KD strategy that integrates KF and adaptive KDloss to enhance knowledge transfer. Moreover, the STG module alleviates response time variations across electrodes, thereby improving feature extraction and eliminating irrelevant information. Experimental results demonstrate that the MTKDDP framework consistently outperforms SOTA methods, achieving higher accuracy on the DEAP and DREAMER datasets. While the current work remains at the experimental stage and has not yet been clinically deployed, these findings indicate strong potential for future applications in real-world clinical scenarios.

However, MTKDDP still requires further verification on diverse cross-domain EEG datasets. As more EEG signals become available, the framework can add subnets to improve performance and generalization, though with higher computational cost. To address this, future work applies a pruning strategy, stopping training when feature similarity among three consecutive subnets exceeds a threshold. Despite more subnets, each maintains a small number of parameters, keeping the overall model size manageable for practical deployment.

The datasets used and analyzed in the present study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

JQY, THG, and CL designed the research study. JQY and THG performed the research. CL and JZX provided help and advice on the experiments, JZX analyzed the data, and JQY drafted the manuscript. THG and CL guided the experimental design and revised the article. All authors contributed to critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This work is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No.62403264, China Postdoctoral Science Foundation under Grant No.2024M761556, Qing-dao Natural Science Foundation under Grant No.24-4-4-zrjj-94-jch, Postdoctoral Innovation Project of Shandong Province under Grant No.SDCX-ZG 202400312, Qingdao Postdoctoral Applied Foundation under Grant No.QDBSH20240102029, Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province under Grant No.ZR2025ZD15 and Systems Science Plus Joint Research Program of Qingdao University under Grant No.XT2024202.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.