1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a typical form of dementia familiar to the public

for which aging is the primary risk factor. Longer life expectancies increase the

risk of people suffering from AD [1]. Alzheimer’s patients typically encounter

memory deficits and reduced cognitive abilities alongside other complications,

with the chronic nature of their condition creating escalating burdens for family

systems and society at large [2]. Hence, the development of efficient therapies

for AD has become a pressing necessity. Pathologically, AD is distinguished from

other forms of dementia by the appearance of Amyloid-beta (A) plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) [3], which are considered the cornerstone of its pathogenesis.

Despite the approval of lecanemab, a new monoclonal antibody that targets

A elimination, by the Food and Drug Administration earlier this year

[4], advancements in drug development focused on A and NFTs have

continued to progress at a sluggish pace over recent decades [5]. Therefore,

other important factors are also involved in AD progression.

The central role of glial cell-driven neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s

pathogenesis is gaining growing recognition. A positron emission tomography (PET)

imaging study has demonstrated that neuroinflammatory processes initiate at

preclinical stages, preceding A plaque deposition—a finding

replicated in multiple transgenic rodent models [6]. Longitudinal observations

reveal sustained activation of microglial cells in AD-affected brains [7]. A

systematic review documented altered expression of inflammatory biomarkers in

both central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral compartments, corroborating the systemic inflammatory

phenotype of AD [8]. Mechanistically, A accumulation promotes

neuroinflammatory responses marked by cytokine secretion and activation of

canonical signaling pathways including nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-B) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) [9]. Moreover, the

heightened neuroinflammation fosters the production of additional A

plaques, leading to a vicious circle [10]. Neflamapimod, a selective inhibitor of

p38 MAPK pathway, was confirmed to dampen biomarkers of synaptic impairment in

the cerebrospinal fluid in a phase 2 clinical trial, which deserves further

clinical trials before its application [11]. Thus, focusing on neuroinflammation

may offer a potential pathway for the creation of therapeutic agents to tackle

AD.

Due to their abundant sources and excellent safety profile, natural products and

their derivatives have garnered increasing attention in the field of drug

development [12]. In addition, their diverse and complex chemical structures may

be sued to develop multi-target drugs [13]. For example, ferulic acid protected

the hippocampal capillaries, lessened A aggregation, and improved memory

deficits in Mo/HuAPP695swe (APP)/PS1-dE9 (PS1) mice [14], which also regulated

oxidative stress and inflammation. Rubiadin (RB) is an anthraquinone compound

that mainly originates from the root of Rubia cordifolia Linn., an ancient

medicinal plant found in Ayurveda [15]. RB has been documented to exhibit a broad

spectrum of pharmacological activities, such as anticancer, anti-osteoporotic,

hepatoprotective, antidiabetic, antioxidant, antifungal, and anti-inflammatory

effects [16]. In particular, 500 mg of the RB suspension improved epileptic

seizures caused by maximal electric shock and pentylene tetrazole, indicating its

neuroprotective effects. However, no studies have explored whether RB plays a

neuroprotective role in AD-related rodent or cell models.

This study systematically evaluated the neuroprotective efficacy of RB in

Alzheimer’s disease using transgenic APP/PS1 mice and

A1–42-challenged N2a cells. Behavioral assessments including

Morris water maze (MWM), step-down/step-through passive avoidance tasks, and

novel object recognition (NOR) were employed to characterize memory improvement

following RB administration. Amyloid plaque burden in APP/PS1 mouse brains was

quantified via immunohistochemical staining, while inflammatory marker expression

was analyzed using western blot techniques. To validate in vitro

neuroprotection, an A1–42-exposed N2a cell model was established,

with cytoprotective effects evaluated through cell viability assays, western blot

analysis, and immunofluorescence microscopy. Collectively, these findings

contribute preclinical evidence supporting RB’s therapeutic potential and

facilitate translational research toward AD treatment development.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Animals

Twenty APP/PS1 mice (8-month-old, 44–50 g) and ten wild-type (WT) littermate

mice (8-month-old, 38–44 g) were provided by Liaoning Changsheng Biotechnology

Co., Ltd. (Benxi, Liaoning, China). All mice stayed in the SPF-level laboratory,

where each mouse lived in a single cage with sufficient water and food. 10 WT

mice were included in the WT group (n = 10). All APP/PS1 mice were randomly and

equally divided into the APP/PS1 group and RB-treated APP/PS1 group (n = 10).

Mice in the WT and APP/PS1 group were given normal saline (0.9%) orally every

day, while the RB-treated APP/PS1 mice were treated with 20 mg/kg RB (117-02-2,

Chengdu Herbpurify Co., Ltd., Chengdu, Sichuan, China) through the same way. The

intragastric administration dose was 0.1 mL/10 g, which means 0.1 mL was given

for every 10 g of mouse body weight. The whole agent treatment lasted for 8 weeks

and behavioral tests began since the 6th week. Subsequently, the mice were

intraperitoneally injected with 150 mg/kg of pentobarbital (P3761, Sigma-Aldrich, Shanghai, China) sodium and their brain samples were procured for subsequent experimental

analysis. Animal experiments were approved by Institutional Animal Care, use

Committee of Jilin University (SY202103007), and the date (10-03-2021) of this

approval. All procedures were in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines.

2.2 MWM Test

The MWM test was conducted on the 36th day. MWM test included 2 parts, the 6-day

navigation test and 1-day probe trial. In the navigation test, mice were put into

the muddy water containing TiO2 in the tank which is 120 cm in diameter.

Their goal was to find the platform, which was hidden 2 cm below the water

surface, within a 60 s time limit. If they were unsuccessful in finding the

platform, they would be guided to it and required to stay there for 30 s to

become familiar with its location. All mice were trained for 5 days and the

formal test was carried out on the 6th day (day 41st since the beginning of agent

treatment). In the probe trial, the platform was taken away, and the mice were

permitted to swim freely in the opaque water for 60 s. A video tracking system

(XR-XM101, Shanghai XinRuan Information Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) was utilized to record the every-day escape latency, the crossing

numbers in the platform area and time staying in this area in the probe trail,

and their trajectories. Data analysis was conducted by an observer unaware of the

treatment conditions.

2.3 Step-Down and Step-Through Passive Avoidance Test

Since the 44th day, the step-down test was initiated. The equipment consisted of

was a square box (30 cm 30 cm 30 cm), with a circular

platform (8 cm in diameter) positioned at its center (XR-3TB, Shanghai XinRuan

Information Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). This platform was elevated 4

cm above a grid floor made of stainless steel. As previously mentioned, the mice

were initially placed on the grid floor and subjected to an electric shock,

prompting them to jump onto the platform to evade the stimulus. Following a

24-hour interval, the mice were placed on the platform again. The step-down

latency was determined by measuring the time it took for each mouse to jump back

down to the floor for the first time. A maximum step-through latency of 300 s was

established. During this period, the number of times each mouse jumped down was

recorded as error counts.

The step-through test [17] was performed since day 47th. The apparatus comprised

two identical compartments (each measuring 20 cm 13 cm 12

cm), one illuminated and the other dark (XR-Med, Shanghai XinRuan Information

Technology Co., Ltd.). An automated doorway separated these two

compartments. The floor in the dark compartment was charged with electricity. In

the training session, the mice were first put in the light compartment for 10 s

of free exploration. Later, the door was opened, and driven by their natural

curiosity, the mice were inclined to enter the dark compartment. Upon chamber

entry, the door was shut, and subjects received a 0.2 mA electric foot shock for

5 seconds. After a 48-hour interval, mice were placed back into the light

compartment with the open-door configuration. The latency to enter the dark

compartment was measured as step-through latency, with a 300-second ceiling.

Blinded evaluation was conducted by an observer unaware of treatment assignments.

2.4 NOR Test

On day 50th, NOR test was performed referring to Wan et al. [18].

Initially, the mice were permitted to explore an empty apparatus (50 cm

50 cm) for a period of 5 min to become accustomed to the environment.

Subsequently, two identical objects, labeled A and B, were introduced into the

apparatus, and the mice were given an additional 5 min to explore. Following the

exploration phase, the mice were taken out, and the apparatus was meticulously

cleaned with 75% ethyl alcohol to remove any remaining odors. Then, object B was

substituted with a new object C, which was identical in size and material but

featured a distinct shape. The time spent by the mice exploring each object was

meticulously recorded by a video tracking system (XR-XM101). The recognition index (%) was calculated using

the formula: New object exploration time / (new object exploration time + old

object exploration time) 100%. Data analysis was carried out by an

observer unaware of the treatment groups to maintain objectivity.

2.5 Immunohistochemistry (IHC) Analysis

The general health status of the mice was closely monitored throughout the entire experimental period. Following the completion of behavioral tests, all mice were euthanized using CO2 anesthesia. CO2 was displaced into the euthanasia vessel at a flow rate of 40% of the chamber’s volume per minute. Like Wan et al. [18], after mice were euthanized, the intact brain

samples were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (BL539A, biosharp, Hefei, Anhui,

China) instantly followed by dehydration and embedding. The paraffin-embedded

blocks were cut into slices with a thickness of 5 µm. After re-hydrated,

slices were subjected to antigen retrieval at 96 °C. Then slices were sequentially

blocked with 5% bull serum albumin (abs9157, Absin (Shanghai) Bioscience Inc., Ltd., Shanghai, China), incubated with anti-A1–42 (A24422, 1:500,

ABclonal, Wuhan, China) and secondary antibody (E-AB-1003, 1:5000, Elabscience,

Wuhan, Hubei, China), and finally stained with DAB and hematoxylin. All agents

were from IHC detection kit (RK05872, ABclonal). Images were

taken using microscope (BX51, Olympus, Beijing, China). For all antibodies’ information see Supplementary Material-antibodies.

2.6 Cell Culture and Agent Treatment

N2a cells are a neuroblastoma cell line with neuronal and amoeboid stem cell

morphology isolated from brain tissue. Mouse neuroblastoma N2a cells (CL-0168,

Procell, Wuhan, Hubei, China) were maintained in MEM medium (11575032)

supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (16140071) and 1%

penicillin-streptomycin solution (15140148). Cells were cultured at 37

°C in a moist environment with 5% CO2. All reagents were offered

by Thermo (Waltham, MA, USA). The N2a cells used in the experiment were

morphologically characterized and confirmed to be free of mycoplasma

contamination.

For the agent treatment in the following experiments, in the 3 h pretreatment

period, N2a cells in the RB-treated groups were treated with 5 µM RB and 20

µM RB, respectively. In both the control and model groups, the medium was

replaced with an equal volume of basic MEM. Then in the 24 h treatment period,

the control group was still treated with basic MEM. The model group was treated

with 5 µM A1–42 (107P64, Taigu Biology, Nanjing, Jiangsu,

China). The RB-treated groups were firstly stimulated with 5 µM

A1–42, then treated with 5 µM RB and 20 µM RB,

respectively.

2.7 Cell Viability Test

This part refers to the previous method [19]. 100 µL of N2a cell

suspension were added in the 96-well plate (5 104/mL) for cell

viability test. Following the pretreatment for 3 h and treatment for 24 h as

described in the “Cell Culture and Agent Treatment” section, 20 µL of a 5

mg/kg MTT (1334GR001, Guangzhou saiquo biotech Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, Guangdong, China) solution was added to the cells. Following incubation at 37 °C

for 4 hours. The crystals were dissolved using dimethyl sulfoxide (D670381, Aladdin,

Shanghai, China) and the absorbance was measured at 490 nm using microplate

reader (Synergy 4, Omega Bio-tek, Inc., Norcross, GA, USA).

2.8 Cell Immunofluorescence

N2a cells were plated at 5 104 cells/mL on glass coverslips to

evaluate nuclear translocation of NF-B following RB treatment. After

completing the pre-treatment and drug administration protocols described in

section 2.6, culture medium was aspirated, and cells were washed with phosphate

buffer. Sample preparation followed the manufacturer’s instructions (SN368, Beyotime, Beijing, China). The

slides were incubated with NF-B (A2547, 1:300, ABclonal) antibodies,

followed by secondary antibody (AS058, 1:500, ABclonal), and

ultimately with DAPI (D1306, Thermofisher, Waltham, MA, USA). Confocal imaging was performed using a Zeiss LSM710 laser

scanning microscope (Shanghai, China). For all antibodies’ information see Supplementary Material-antibodies.

2.9 Western Blot

Brain sample were collected to homogenize (50 Hz, 60 s, twice) and centrifuge

(13,000 rpm, 5 min, twice) to extract protein solution. After treatment was

finished as shown in 2.6, N2a cells were collected to lyse (20 min) and

centrifuge (13,000 rpm, 5 min, twice) to extract protein sample. The whole

process of protein extraction was done under 4 °C. The solution was qualified

using BCA kit (P0012S, beyotime, Shanghai, China). Proteins (30–40 µg)

were separated using sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

(SDS-PAGE) and then transferred to PVDF membranes. Primary antibodies

anti-IL-1 (A16288, 1:1000, ABclonal), anti-IL-4 (A14660, 1:1000,

ABclonal), anti-IL-6 (A0286, 1:1000, ABclonal), anti-TNF- (A11534,

1:1000, ABclonal), anti-p-inhibitor of kappa B kinase (IKK) (AP0546, 1:1000,

ABclonal), anti-IKK (A2062, 1:3000, ABclonal), anti-p-inhibitor of

NF-B (IB) (AP0614, 1:500, ABclonal), anti-IB

(A11397, 1:1000, ABclonal), anti-p-nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-B)

(AP0123, 1:400, ABclonal), anti-NF-B (A2547, 1:1000, ABclonal),

anti-p-Tau (bs-2392R, 1:2000, Bioss, Beijing, China) and anti-GAPDH (A19056,

1:5000, ABclonal) were used to incubate membranes at 4 °C overnight. The membranes

were subsequently washed and incubated with goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G

(IgG) (AS058, 1:10,000, ABclonal) at 4 °C for 4 hours. After incubation,

membranes were washed again and analyzed by gel imager (GenoSens 2150, Beijing,

China). For all antibodies’ information see Supplementary Material-antibodies.

2.10 Statistical Analysis

Semi-quantitative analysis of immunohistochemical staining and western blot

results was performed using ImageJ software (1.8.0.345, Bethesda, MD, USA). GraphPad Prism 9

(GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) was utilized to generate bar charts. Statistical comparisons

among WT, APP/PS1, and RB-treated APP/PS1 groups were conducted with BONC DSS

Statistics 25 software (Business-intelligence of Oriental Nations Co., Ltd., Beijing, China), presenting data as mean

(standard error of the mean) SEM. The normality of the behavioral data was

assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and non-parametric statistical analysis was

conducted via the Kruskal-Wallis H test due to potential deviations from normal

distribution. For the comparison of multiple groups in the other data, one-way

ANOVA was performed, followed by Least Significant Difference (LSD) post hoc analysis. Statistical significance

was determined at p 0.05. For original data see Supplementary Material-Original data.

3. Results

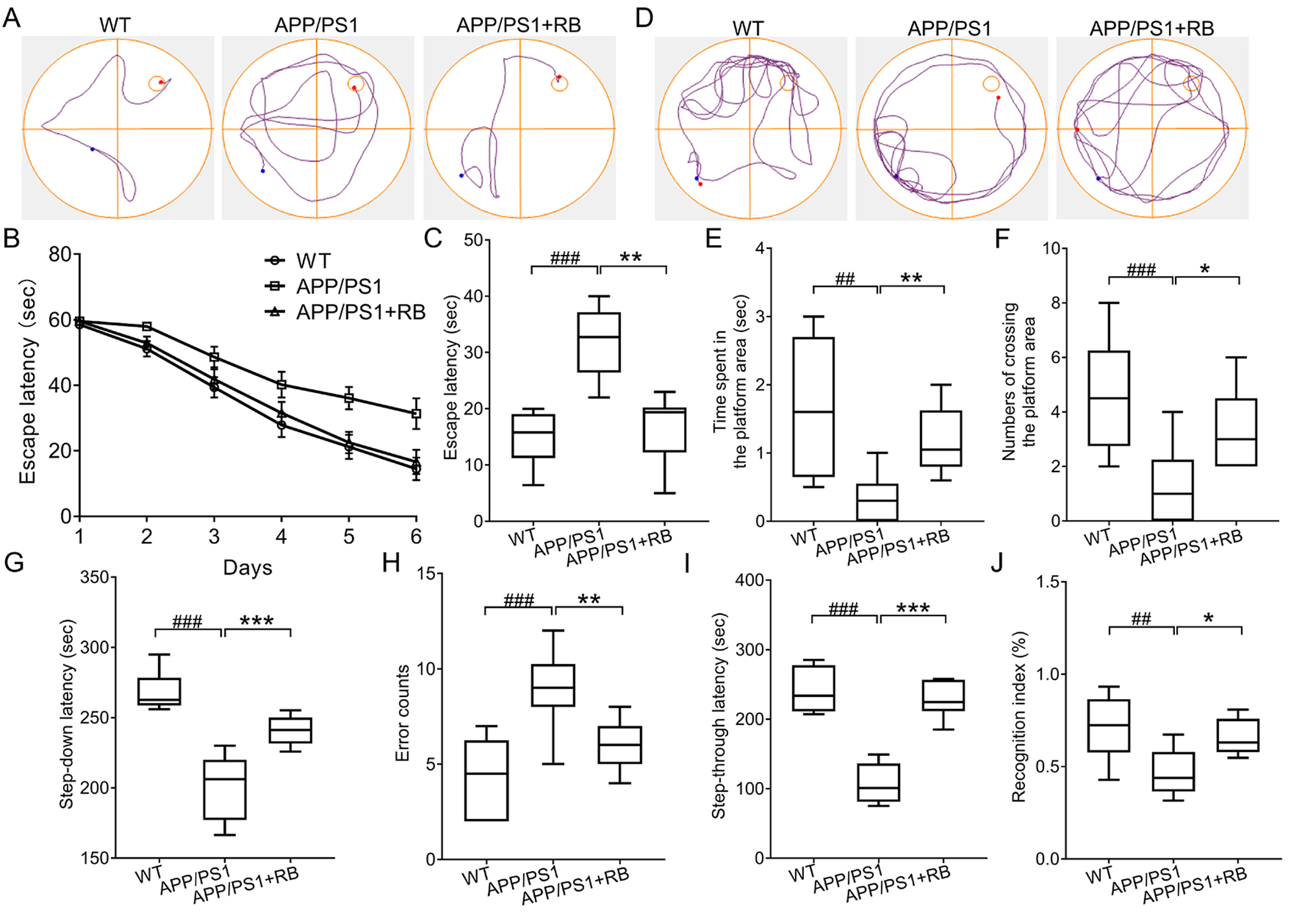

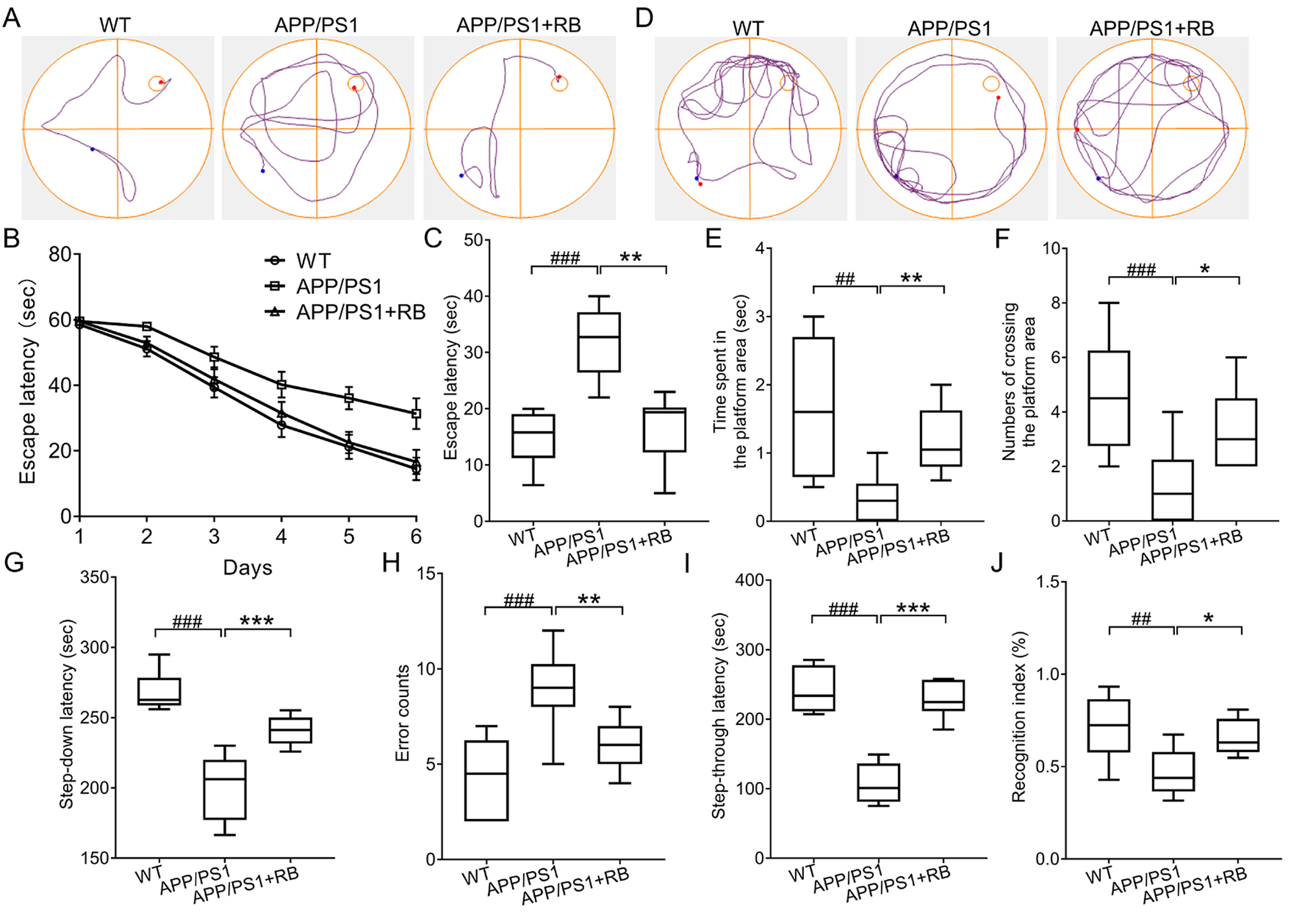

3.1 RB Ameliorated Memory Loss and Learning Ability of APP/PS1 Mice

MWM is widely utilized to evaluate spatial memory and learning capacities in

rodent models [20]. Representative swimming trajectories on day 6 are presented

in Fig. 1A. During the initial navigation session, no significant differences in

platform localization time were observed among WT, APP/PS1, and APP/PS1 + RB

groups (Fig. 1B). Following repeated training, RB-treated APP/PS1 mice

demonstrated reduced search times compared to untreated counterparts (Fig. 1B).

Notably, APP/PS1 mice displayed more disorganized swimming patterns compared to

RB-treated animals. Statistical analysis revealed that RB administration

significantly decreased escape latency during formal navigation testing in

APP/PS1 mice (p 0.01) (Fig. 1C). Probe trial results showed distinct

trajectory patterns (Fig. 1D), with APP/PS1 mice spending significantly less time

in the target quadrant compared to WT controls (p 0.01) (Fig. 1E).

Additionally, platform crossings were reduced in APP/PS1 mice (p 0.001) (Fig. 1F). Significantly, RB intervention enhanced both target area

occupancy and platform crossing frequency in APP/PS1 mice (p 0.05,

Fig. 1E,F). Passive avoidance testing (step-down/step-through) evaluated memory

function following RB administration. Step-down test results showed APP/PS1 mice

had shorter latency to step down compared to WT controls (p 0.001,

Fig. 1G). Additionally, APP/PS1 mice made more jump-down attempts within 5

minutes despite repeated shocks (p 0.001, Fig. 1H). RB treatment

reversed these impairments in APP/PS1 mice, increasing step-down latency

(p 0.001, Fig. 1G) and reducing jump-down frequency (p 0.01, Fig. 1H). Step-through test results revealed RB-treated mice had

significantly longer latency to enter the dark compartment compared to untreated

APP/PS1 mice (p 0.001, Fig. 1I). NOR test results showed APP/PS1

mice had impaired non-spatial recognition memory, reflected by reduced

recognition index, which was improved by RB treatment (p 0.05, Fig. 1J). These data indicate RB improves both spatial and non-spatial memory in

APP/PS1 mice.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

RB ameliorated memory loss and learning ability of

APP/PS1 mice. (A) Represent trajectories on day 6 in the navigation test

(n = 10). The escape latency (B) from day 1 to day 6 and (C) on day 6 in

the navigation part of MWM test (n = 10). (D) Represent trajectories of

mice in the probe trial (n = 10). RB increased (E) time that mice spent

in the platform area and (F) numbers of crossing the platform area (n =

10). (G,H) RB improved the memory performance of APP/PS1 mice in the step-down

passive avoidance test (n = 10). (I) RB extended the step-through

latency of APP/PS1 mice in the step-through passive avoidance test (n =

10). (J) RB enhanced the recognition index of APP/PS1 mice in the NOR test

(n = 10). ##p 0.01, ###p 0.001

compared with WT mice; *p 0.05, **p 0.01, and

***p 0.001 compared with APP/PS1 mice. RB, rubiadin; APP/PS1,

Mo/HuAPP695swe/PS1-dE9; MWM, Morris water maze; NOR, novel object recognition;

WT, wild-type.

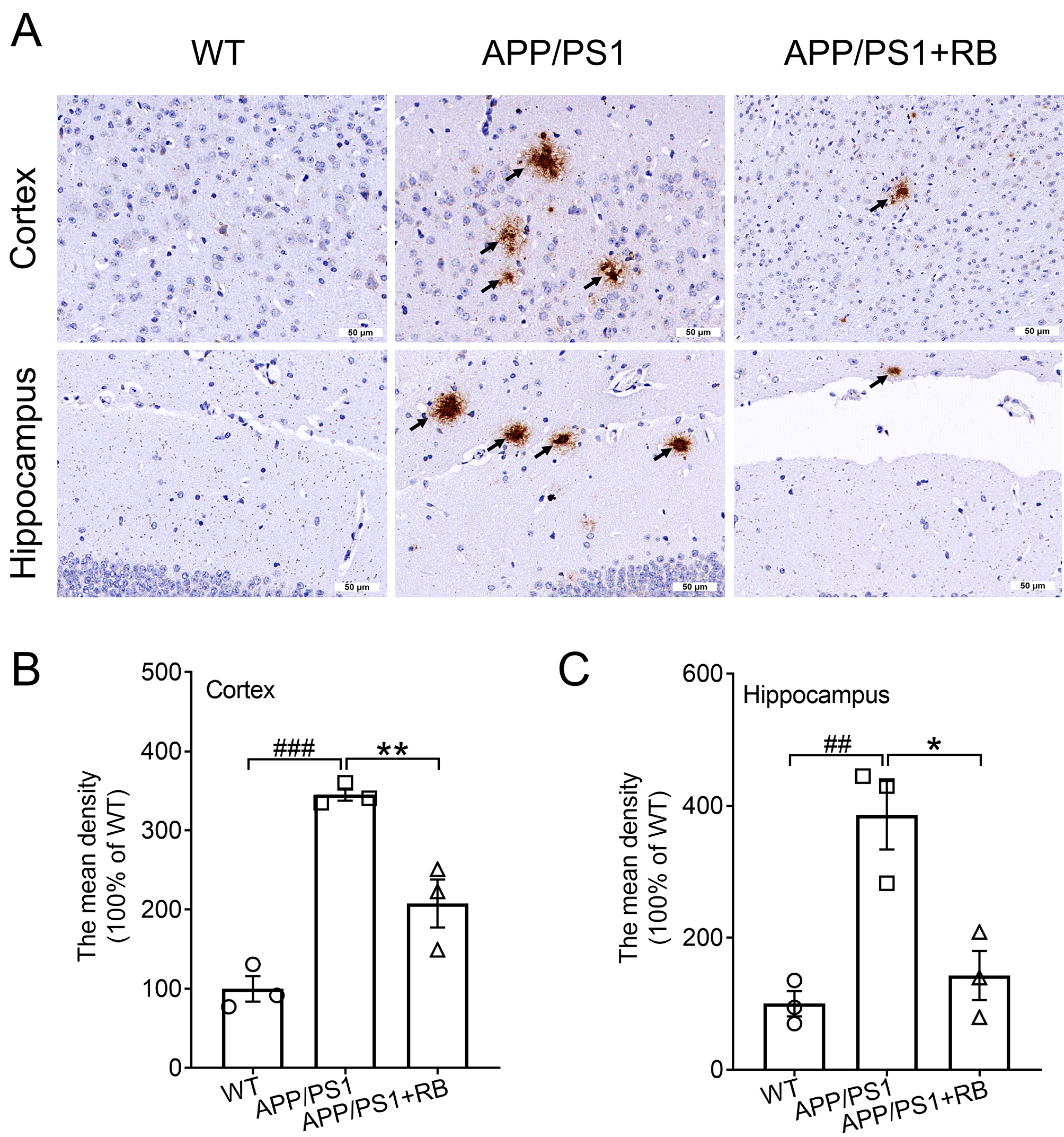

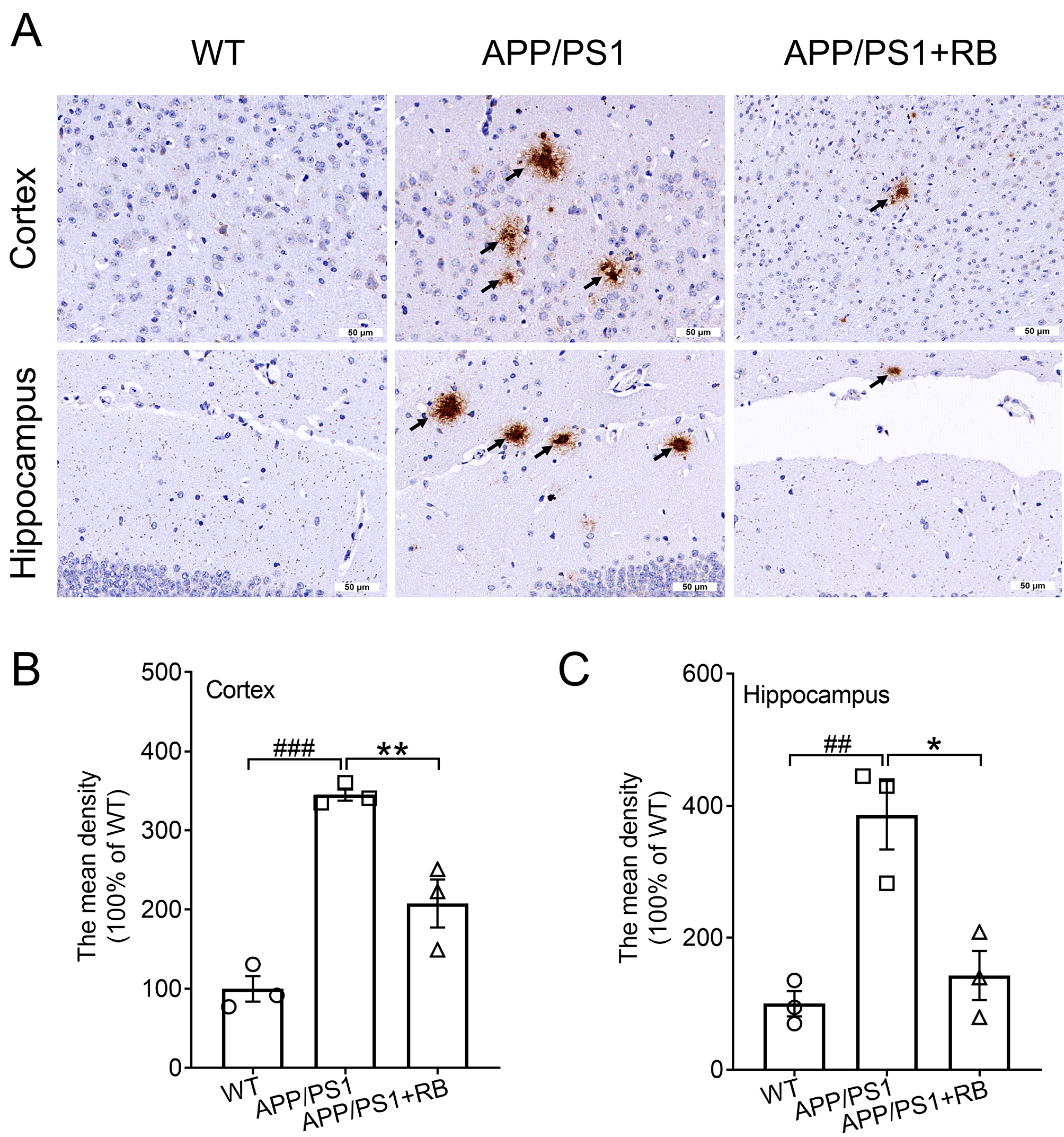

3.2 RB Decreased Cerebral A Deposition and

Neuroinflammation of APP/PS1 Mice

To investigate the pathological effects of RB treatment in APP/PS1 mice,

immunohistochemical staining was performed to assess A plaque

distribution in cortical and hippocampal areas. Fig. 2 demonstrates that WT mice

had almost no A plaques, whereas APP/PS1 mice exhibited substantial

A accumulation in these regions (p 0.01). Strikingly,

RB-treated APP/PS1 mice showed significant reductions in A plaque

formation in both the cortex and hippocampus (p 0.05, Fig. 2A–C).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

RB inhibited deposition of A plaques in the

brains of APP/PS1 mice. Example images showing A deposition in the (A)

cortex and (C) hippocampus of APP/PS1 mice (n = 3). Scale bar is equal

to 50 µm for 40 and 200 magnification,

respectively. The arrows indicate the A plaques in the cortex and

hippocampus. Semi-quantitative analysis of A deposition in the (B)

cortex and (C) hippocampus of APP/PS1 mice, expressed as the fold change relative

to the WT group (n = 3). Results were presented as means SEM.

##p 0.01 and ###p 0.001 compared with WT

mice; *p 0.05 and **p 0.01 compared with APP/PS1 mice.

SEM, standard error of the mean.

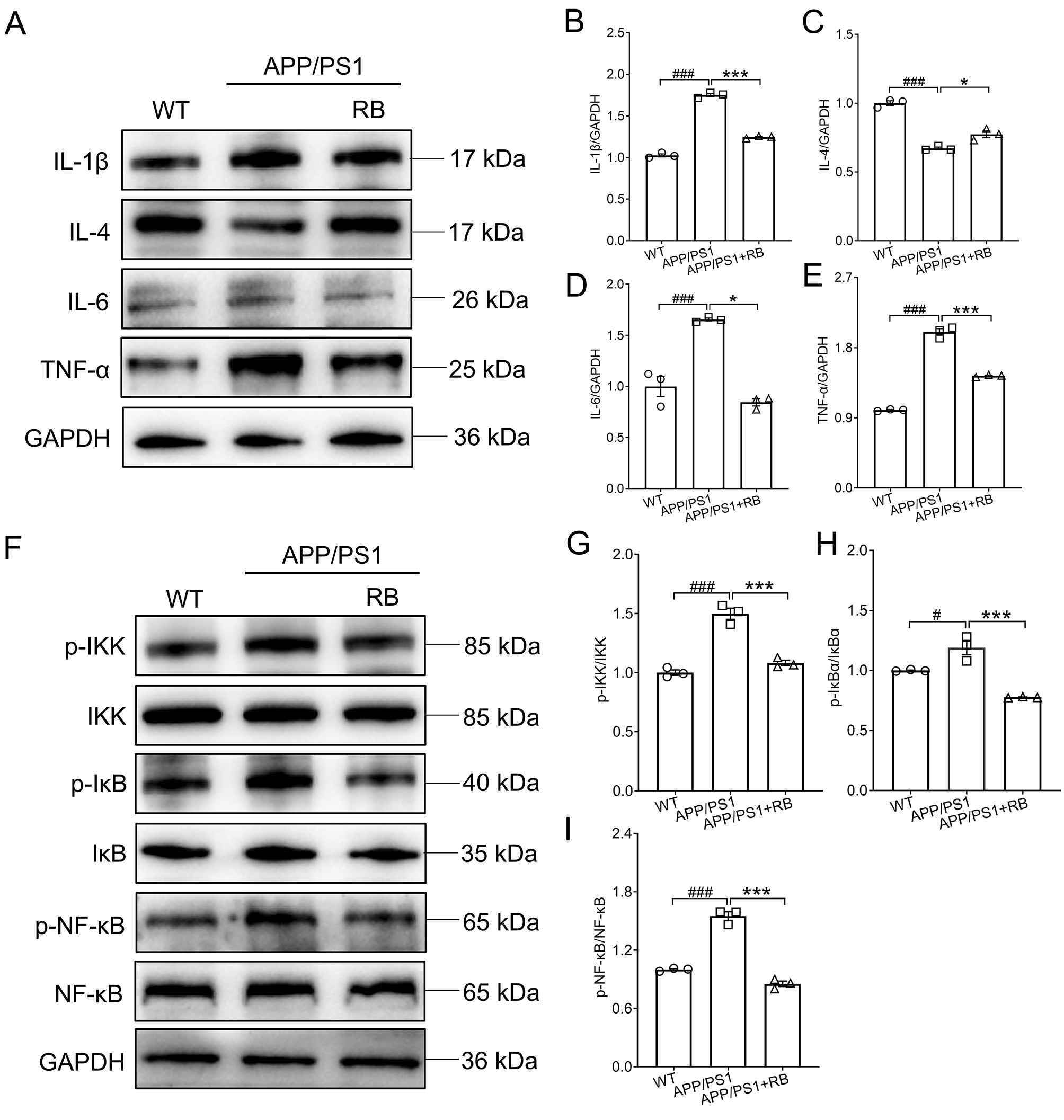

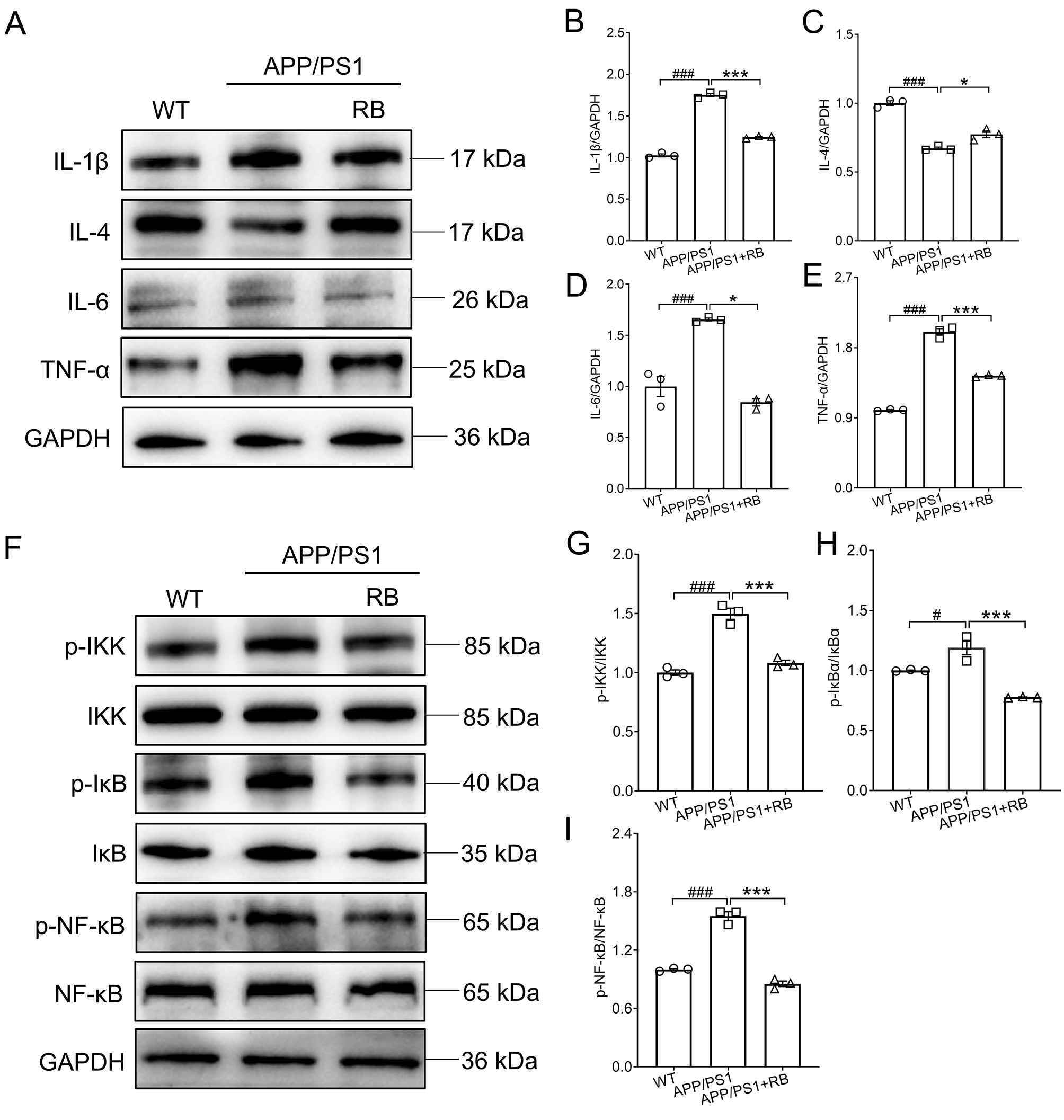

Subsequently, western blot analysis was performed to assess inflammatory markers

in APP/PS1 mouse brains. Compared to WT mice, APP/PS1 mice showed increased

pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1, IL-6, TNF-) and decreased

anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-4 (p 0.001, Fig. 3A–E). RB treatment

significantly reversed these alterations, reducing pro-inflammatory markers and

increasing IL-4 levels (p 0.05, Fig. 3A–E), confirming its

anti-inflammatory properties. Phosphorylation of NF-B signaling

components was also evaluated. RB treatment significantly suppressed

phosphorylation of IKK, IB, and NF-B in APP/PS1 mice compared

to untreated controls (p 0.001, Fig. 3F–I), further supporting its

role in mitigating neuroinflammation. For all original WB figures in Fig. 3A,F,

see the Supplementary Material-original images of WB.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

RB suppressed neuroinflammation in the brains of

APP/PS1 mice. (A) RB blocked the production of IL-1, IL-6, and

TNF- and promoted that of IL-4 in the brains of APP/PS1 mice

(n = 3). Semi-quantitative analysis of (B) IL-1, (C) IL-4, (D)

IL-6, and (E) TNF- which was normalized to GAPDH and presented as the

fold of the WT group (n = 3). (F) RB blunted the activation of

IKK/IB/NF-B in the brains of APP/PS1 mice (n = 3).

Semi-quantitative analysis of (G) p-IKK, (H) p-IB, and (I)

p-NF-B which was normalized to their total proteins and presented as

the fold of the WT group (n = 3). Results were presented as means

SEM. #p 0.05 and ###p 0.001

compared with WT mice; *p 0.05 and ***p 0.001 compared

with APP/PS1 mice. IKK, inhibitor of kappa B kinase; IB, inhibitor of

NF-B; NF-B, p-nuclear factor kappa-B.

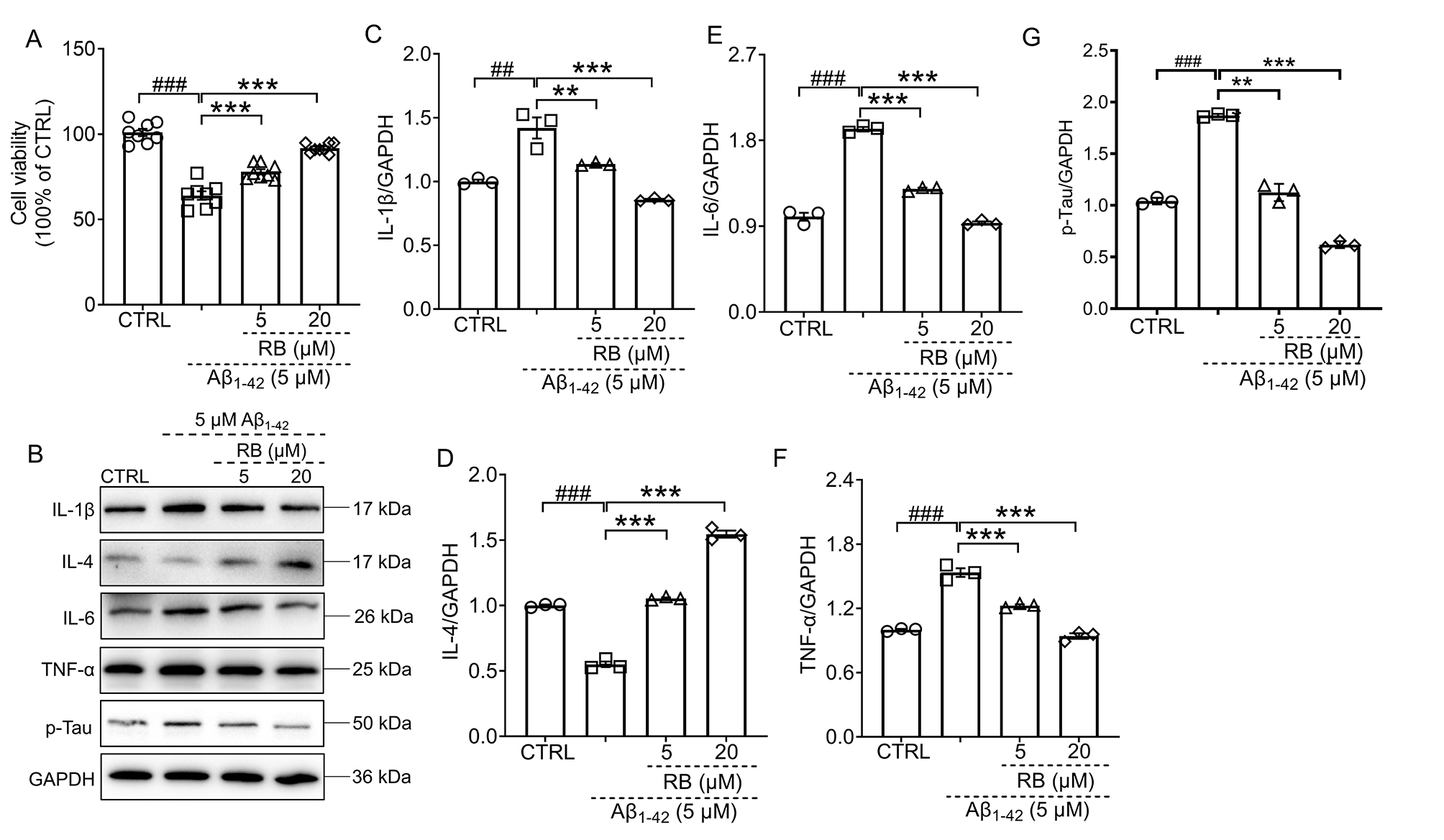

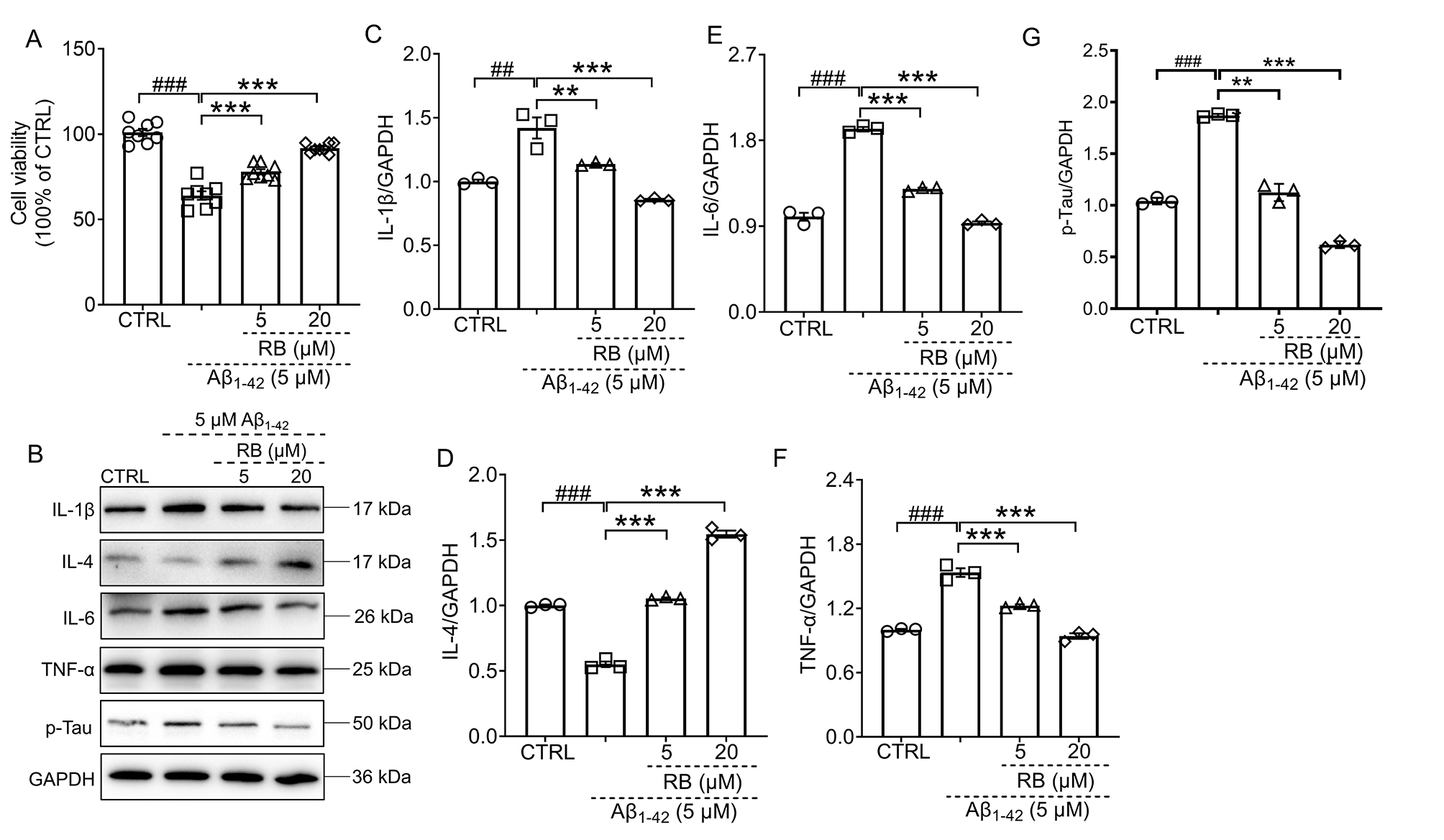

3.3 RB Protected N2a Cells Against A1–42-Induced Cell

Damage and Inflammation

To further validate RB’s neuroprotective effects in vitro, N2a cells

were challenged with A1–42. RB treatment significantly improved

cell viability in A1–42-exposed N2a cells (p 0.001,

Fig. 4A), indicating its cytoprotective potential. Compared to control cells,

A1–42 exposure induced marked increases in pro-inflammatory

cytokines (IL-1, IL-6, TNF-) and decreases in

anti-inflammatory IL-4 (p 0.01, Fig. 4B–F), reflecting inflammatory

activation. For all original WB figures in Fig. 4B, see the Supplementary Material-original images of WB. Concurrently, A1–42 treatment significantly upregulated

phosphorylated Tau protein expression in N2a cells (p 0.001, Fig. 4G). RB administration effectively restored cytokine balance and reduced p-Tau

levels in A1–42-treated cells (p 0.01, Fig. 4B–G),

demonstrating its inhibitory effects on inflammatory responses.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

RB protected N2a cells against A1–42-induced cell

damage and inflammation. (A) RB improved cell viability of

A1–42-induced N2a cells (n = 8). (B) RB suppressed the

production of IL-1, IL-6, TNF- and p-Tau and increased that of

IL-4 in the A1–42-exposed N2a cells (n = 3).

Semi-quantitative analysis of (C) IL-1, (D) IL-4, (E) IL-6, (F)

TNF- and (G) p-Tau was conducted, with expression levels normalized to

GAPDH and expressed as fold change relative to the CTRL N2a group (n =

3). Results were presented as means SEM. ##p 0.01 and

###p 0.001 compared with CTRL N2a cells; **p 0.01 and ***p 0.001 compared with A1–42-exposed N2a

cells.

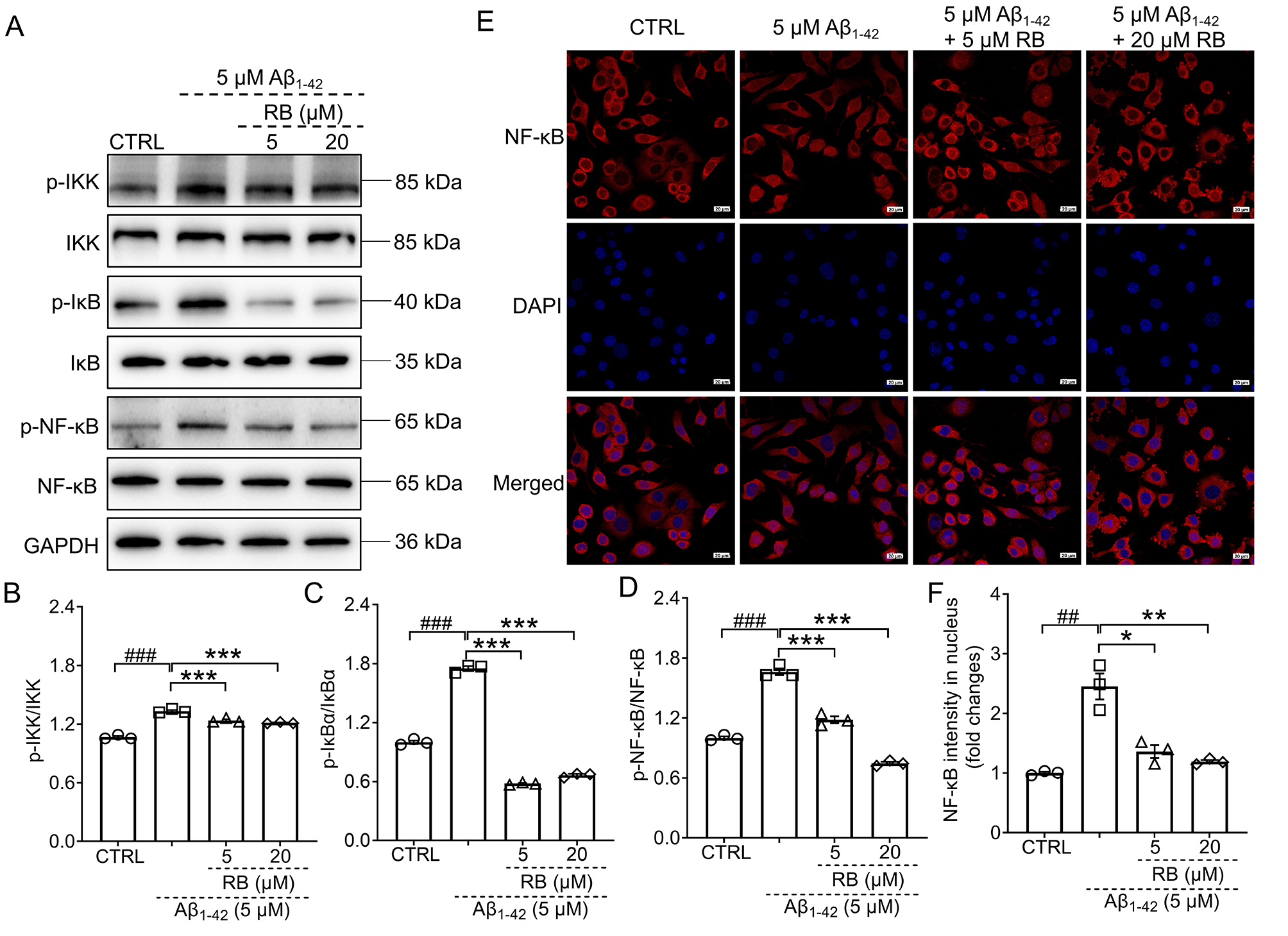

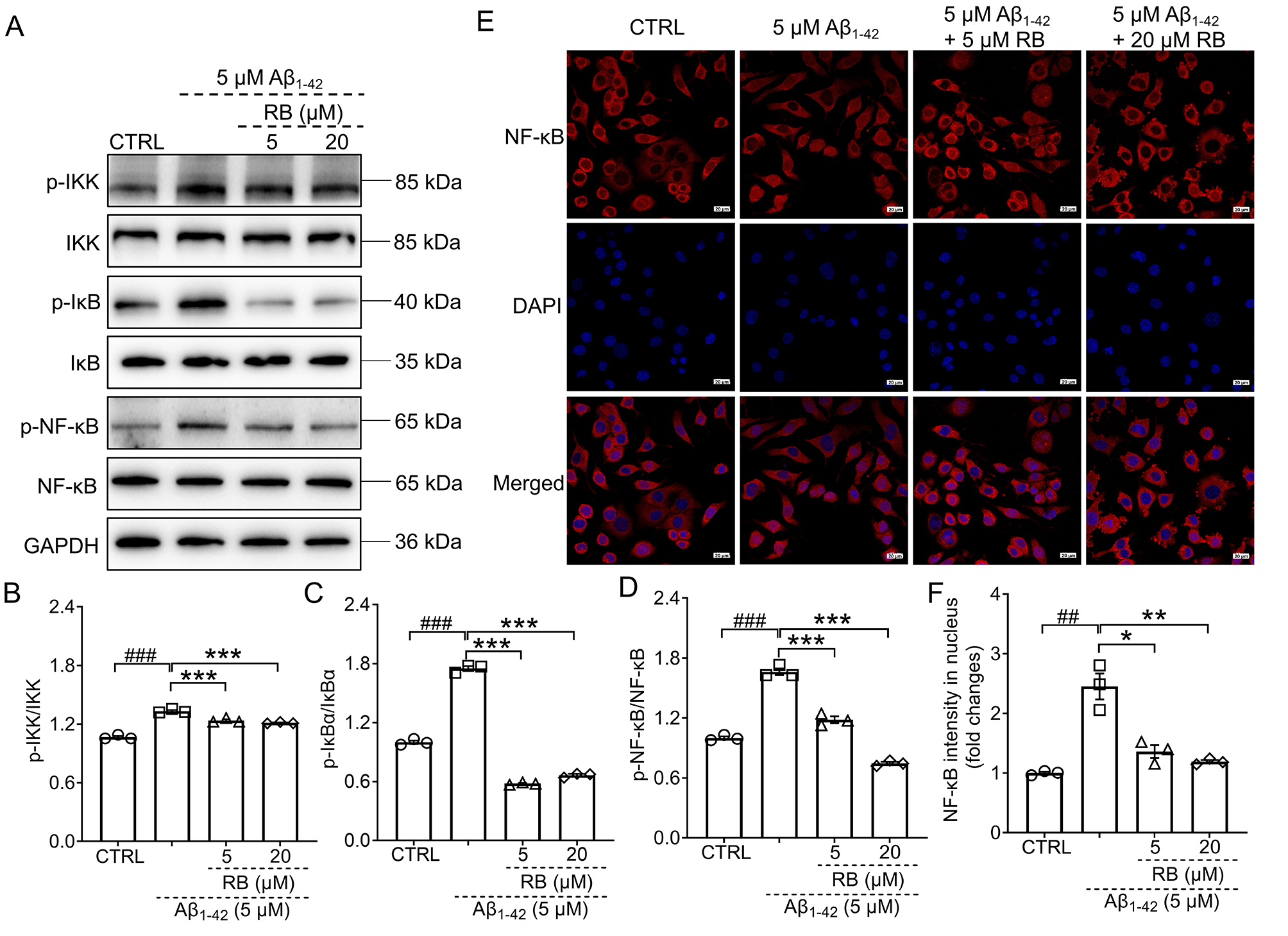

3.4 RB Blunted the Activation of IKK/IB/NF-B

Pathway

To further confirm whether NF-B was regulated in

A1–42-treated N2a cells, the phosphorylation of NF-B and

its upstream IKK and IB was detected through western blot. Once the N2a

cells were treated with 5 µM A1–42, the expression levels of

phosphorylated IKK, IB, and NF-B were all augmented

(p 0.001) (Fig. 5A–D). For all original WB figures in Fig. 5A, see

the Supplementary Material-original images of WB. Both 5 µM and 20 µM RB,

significantly inhibited the activation of IKK, IB, and NF-B

(p 0.05) (Fig. 5A–D). The red fluorescence–labeled NF-B

and the blue fluorescence–labeled nucleus overlapped much more in the

A1–42-exposed N2a cells than in the CTRL N2a cells, a phenomenon

that was finally reversed by RB treatment (Fig. 5E). Consequently, these findings

indicate that RB suppresses inflammation in A1–42-treated N2a

cells, which may partially involve the IKK/IB/NF-B pathway (Fig. 5F).

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

RB inhibited the activation of IKK/IB/NF-B

pathway in the A1–42-induced N2a cells. (A) RB down-regulated the

phosphorylation of IKK, IB, and NF-B in the

A1–42-treated N2a cells (n = 3). Semi-quantitative

analysis of (B) p-IKK, (C) p-IB, and (D) p-NF-B which was

normalized to their total proteins and presented as the fold of the control (CTRL) N2a

group (n = 3). (E) RB prevented the nuclear translocation of

NF-B in N2a cells treated with A1–42 (n = 3).

(F) The quantitative results of the nuclear fluorescence intensity of

NF-B were presented (n = 3). Scale bar is equal to 20 µm

for 400 magnification. Results were presented as means SEM.

##p 0.01 and ###p 0.001 compared with

CTRL N2a cells; *p 0.05, **p 0.01 and ***p 0.001 compared with A1–42-exposed N2a cells.

4. Discussion

This study investigated the neuroprotective effects of RB on AD using in

vivo and in vitro models. Memory deficits and learning dysfunction in

the APP/PS1 mice were improved by RB on behavioral tests. RB treatment

significantly inhibited the cerebral expression of A through IHC

analysis. Moreover, neuroinflammation was blunted in the brains of the RB-treated

mice based on decreases in pro-inflammatory cytokines, increases in IL-4, and the

inactivation of IKK/IB/NF-B. Subsequently, the efficacy of RB

in reducing inflammation was further confirmed in N2a cells exposed to

A1–42. RB treatment enhanced the viability of N2a cells exposed to

A1–42, while also modulating the secretion of inflammatory

cytokines and suppressing IKK/IB/NF-B pathway activation, as

well as NF-B nuclear transfer. These findings indicate that RB

alleviates symptoms similar to those of AD, which may act by inhibiting

neuroinflammation. Our study provides an experimental basis for future

pharmacological studies of RB, thus facilitating the development of AD drugs from

natural products.

Natural products have great potential for use in drug development. On one hand,

they can be directly developed as new drugs to treat diseases. However, their

novel and diverse structures make them lead compounds in the synthesis of more

effective drugs [21]. The development of AD drugs has extensively explored

natural products and their derivatives [13]. Emodin belongs to the anthraquinone

family and inhibits the amyloidogenic pathway, NFT formation, neuroinflammation,

and oxidative stress in AD-related cells and rodent models [22]. RB is also an

anthraquinone compound whose antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antidiabetic, and

hepatoprotective effects have already been identified. RB is also a component of

the traditional Chinese medicine Jia-Jian-Di-Huang-Yin-Zi decoction, which

enhances behavioral performance and protects dopaminergic neurons from apoptosis

in Parkinson’s disease. Our study focused solely on the RB monomer as the subject

of investigation. RB treatment significantly improved spatial memory in APP/PS1

mice, as evidenced by reduced escape latency during MWM navigation and increased

target quadrant occupancy/crossings during probe trials. Non-spatial memory

enhancements were observed through multiple behavioral measures: increased

latency in step-down/step-through tests, reduced errors in passive avoidance, and

elevated recognition indices in NOR. Pathologically, RB attenuated A

plaque deposition in AD-relevant brain regions. In vitro experiments

confirmed RB protected N2a cells against A1–42-induced

cytotoxicity, supporting its neuroprotective mechanism. These results indicated

that RB relieves AD-like behavioral and pathological symptoms and serves as a

neuroprotective factor in AD.

Inflammatory cytokines play an important role in AD progression. Cerebral

neuronal degeneration in AD is mainly caused by an increase in neuroinflammatory

markers [23]. IL-1 accelerated the apoptosis of hippocampal neurons

treated with A1–42 [24]. Caspase-1 blockade, a key upstream

mediator of IL-1 processing, has been shown to mitigate cognitive

deficits, amyloid- deposition, and neuroinflammation in AD mouse models

[25]. IL-6 is implicated in early amyloid plaque formation and specifically

accumulates within cerebral plaques of AD patients [26]. This cytokine also

promotes tau hyperphosphorylation in hippocampal neurons [27]. Clinically, plasma

IL-6 levels correlate positively with brain inflammation and inversely with

cognitive performance in AD patients [28]. Cerebral IL-6 signaling was further

validated as a mediator of memory impairment in APP/PS1 mice [28]. Elevated

TNF- expression has been confirmed in both blood samples and postmortem

brain tissues of AD patients [29]. After treating AD neurons with TNF-,

researchers detected the formation of abundant protein aggregates which were

composed of A and -synuclein [30]. TNF- and its

receptor regulated neuronal necroptosis as confirmed both in vitro and

in vivo [31]. In a phase II trial, Etanercept, a TNF-

inhibitor, demonstrated favorable safety in 20 AD patients but did not result in

any significant changes in cognitive performance [32]. On the other hand, IL-4

overexpression in the brains of APP/PS1 mice improved AD pathogenesis including

decreased A deposition and gliosis and increased neurogenesis [33]. All

of the above studies imply that it may be effective to alleviate AD by regulating

inflammatory cytokines. In our study, RB reduced the expression levels of

IL-1, IL-6, and TNF- while increasing the expression of IL-4

in both APP/PS1 mice and A1–42-induced N2a cells. These results

indicate that the anti-AD effects of RB might be due to its capacity to reduce

neuroinflammation.

As one of the best-studied pathways, NF-B signaling is involved in

neurodegenerative diseases [34]. For example, nuclear NF-B regulated

-secretase expression at the transcriptional level, accelerating amyloid

precursor protein processing and A expression [35]. NF-B

signaling was also increased in reactive microglia and astrocytes to amplify the

neuroinflammation and aggregate neurodegeneration [36]. Additionally,

NF-B also exerted its function through regulating apolipoprotein E

activity, glutamate excitotoxicity, microRNA expression, and tau pathology [36].

Diverse natural products have demonstrated favorable pharmacological effects for

regulating NF-B in AD. Resveratrol was confirmed to suppress

NF-B and exert neuroprotection in A25-35-induced PC12

cells [37]. Accordingly, in APP/PS1 mice, RB markedly inhibited IKK,

IB, and NF-B phosphorylation. RB also inactivated

IKK/IB/NF-B pathway in A1–42-treated N2a cells

on western blot and suppressed the nuclear translocation of NF-B on an

immunofluorescence analysis. These results were consistent with the inhibition of

neuroinflammation. Therefore, RB attenuated AD pathogenesis, at least in part, by

inhibiting neuroinflammation via the IKK/IB/NF-B pathway.

This study has several limitations. Only the expression profiles of inflammatory

cytokines in APP/PS1 mouse brains were characterized. Neuroinflammation is

primarily regulated by microglial and astrocytic activation [38]. Future studies

will focus on quantifying microglial and astrocytic activation states in APP/PS1

mice to mechanistically validate RB’s anti-inflammatory effects. On the other

hand, based on the diverse pharmacological effects of RB in different disease

models [16] and since AD is also a complex disease influenced by multiple

factors, we will further explore whether RB has any biological activity other

than anti-neuroinflammatory effects in AD models.

Here we discussed the results and how they compare to those of previous studies

and working hypotheses. These findings and their significance should be

considered in a wider context and explored more thoroughly in future studies.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.