1 Sports, Exercise and Brain Sciences Laboratory, Sports Coaching College, Beijing Sport University, 100084 Beijing, China

2 Department of Psychology and Neurosciences, Leibniz Research Centre for Working Environment and Human Factors, 44139 Dortmund, Germany

3 University Clinic of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Protestant Hospital of Bethel Foundation, University Hospital OWL, Bielefeld University, 33615 Bielefeld, Germany

4 German Centre for Mental Health (DZPG), 44787 Bochum, Germany

5 China Institute of Sport and Health Science, Beijing Sport University, 100084 Beijing, China

Abstract

Sports fatigue in soccer athletes has been shown to decrease neural activity, impairing cognitive function and negatively affecting motor performance. Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) can alter cortical excitability, augment synaptic plasticity, and enhance cognitive function. However, its potential to ameliorate cognitive impairment during sports fatigue remains largely unexplored. This study investigated the effect of dual-site tDCS targeting the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) or primary motor cortex (M1) on attention, decision-making, and working memory in elite soccer athletes during sports fatigue.

Sports fatigue was induced in 23 (non-goalkeeper) elite soccer athletes, who then participated in three counterbalanced intervention sessions: dual-site tDCS over the M1, dual-site tDCS over the DLPFC, and sham tDCS. Following tDCS, participants completed the Stroop, Iowa Gambling, and 2-back tasks.

We found a significant improvement in Stroop task accuracy following dual-site anodal tDCS over the M1 compared with the sham intervention in the incongruent condition (p = 0.036). Net scores in the Iowa Gambling task during blocks 4 (p = 0.019) and 5 (p = 0.014) significantly decreased under dual-site tDCS targeting the DLPFC compared with the sham intervention. No differences in 2-back task performance were observed between sessions (all p > 0.05).

We conclude that dual-site anodal tDCS applied to the M1 enhanced attention performance while tDCS targeting the DLPFC increased risk propensity in a decision-making task during sports fatigue in elite soccer athletes. However, dual-site anodal tDCS targeting either the M1 or DLPFC did not significantly influence working memory performance during sports fatigue in this population. These preliminary findings suggest that dual-site tDCS targeting the M1 has beneficial effects on attention performance, potentially informing future research on sports fatigue in athletes.

No: NCT06594978. Registered 09 September, 2024; https://clinicaltrials.gov/search?cond=NCT06594978.

Keywords

- transcranial direct current stimulation

- primary motor cortex

- prefrontal cortex

- cognitive function

- sports fatigue

Sports fatigue is characterized as a decline in cognitive function and the capacity to sustain the desired level of exercise intensity and originates from muscular contractile properties and central nervous system influences [1, 2]. Research has shown that sports fatigue not only diminishes an athlete’s peak performance [3] but also increases the risk of injuries [4] and affects overall health [5]. Soccer, an endurance-based team sport, is characterized by extended low-intensity activity interspersed with short, frequent high-intensity sprints and dynamic movements, such as changes in direction, passing, dribbling, and tackling [6, 7, 8]. This physically demanding regimen leads to sports fatigue [9], which can diminish high-speed running and the distances sprinted towards the end of a match and reduce the quality of technical performance [10, 11, 12]. Thomas et al. [13] have demonstrated that sports fatigue induced by simulated soccer match-play can last for as long as 72 hours following exercise.

Attention, decision-making, and working memory are critical cognitive functions for the adequate performance of soccer players [14, 15, 16, 17, 18]. These functions involve several brain circuits, including the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), anterior cingulate cortex, and parietal cortex [19]. The prefrontal cortex (PFC) is recognized as a crucial component of the cognitive control network [20, 21]. During a soccer match, players must maintain focus, continuously receive and process information, and execute rapid and precise decisions to navigate interactions with teammates and opponents in a dynamic, fast-paced, and unpredictable environment [22, 23]. However, a review has highlighted sports fatigue’s detrimental effects on team sports players’ decision-making, attention, and perceptual skills [24]. Some studies found that exercise-induced fatigue can increase response time and the number of mistakes [25, 26, 27], impair attentional and perceptual capabilities [28], and disrupt decision-making ability [29]. Research has also shown that excessive physical training leads to cognitive control fatigue and decision-making impulsivity, which are linked to reduced PFC activity [30]. Given the pivotal role of attention, decision-making, and working memory performance in soccer, it is vital to explore methods and interventions that enhance the cognitive functions of soccer players experiencing fatigue.

Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) is a non-invasive brain stimulation technique that modulates cortical excitability and activity based on polarity and operates by delivering a consistent, low-intensity electrical current to designated areas of the brain [31, 32]. This modulation influences the spontaneous firing rates of cortical neurons through depolarization or hyperpolarization of their resting membrane potentials [31, 33]. Notably, the after-effects of tDCS can persist for approximately 90 minutes post-stimulation [33, 34]. tDCS can improve cognitive abilities by modulating cortical plasticity, activating specific brain areas, and impacting cognition-related brain networks by changing their functional connectivity and fostering cooperative interactions among different brain areas [35]. Extensive studies have explored the impacts of tDCS administered to the PFC on cognitive functions in healthy adults [36, 37]. Specifically, studies have demonstrated that anodal tDCS targeting the DLPFC enhances attention [38, 39], improves decision-making [40, 41, 42], and boosts working memory performance [43, 44].

The PFC and the primary motor cortex (M1) are crucial areas shown to substantially impact both cognitive and physical performance [45]. The DLPFC is vital for enhancing fatigue resistance through the regulation of motivation, cognitive control, and decision-making [46, 47, 48]. The primary neuromodulatory role of the DLPFC involves inhibitory control over the amygdala and the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis [47]. This inhibitory capacity primarily depends on its connectivity with subcortical regions [49, 50]. A reduction in PFC oxygenation has consistently been observed to precede the onset of fatigue [51, 52]. During an intense match, the neural activation of DLPFC, which was vital in the cognitive control process, was reduced due to sports fatigue [47]. The reduction in DLPFC impairs the ability to maintain cognitive performance, thus leading to the decline in cognitive functions that are crucial for strategic decision-making, attention and working memory in soccer matches. M1 serves as a hub brain region, processing various inputs from numerous cortical and subcortical areas [53, 54]. M1 is a key cortical area responsible for motor inhibition and managing both the preparation and suppression of movements through its intrinsic motor programming circuits, which encode descending motor commands [55, 56]. The diminished capacity of the M1 to augment the compensatory neural drive for reduced spinal excitability leads to a decline in muscular capacity, resulting in sports fatigue [1, 2, 57]. Impaired cognitive and exercise performance during sports fatigue may be attributed to decreased corticospinal excitability, as well as to reduced motor drive originating from the M1 or an upstream region like the DLPFC. This reduction is caused by the processing of peripheral feedback, various emotional states, motivation, perceived exertion, emotional responses, pain, emotional disorders, and cognitive control [1, 45, 48, 58]. Additionally, the decline in DLPFC induced by sports fatigue may influence its regulatory control over M1, leading to decreased sports performance [45]. The precision and coordination of movement modulated by M1 are impaired due to the declined top-down control to motor functions by the DLPFC [48]. This interconnected phenomenon of alterations in the activity of both the DLPFC and M1, which results in decreased cognitive and motor performance, is a crucial aspect of sports fatigue. Therefore, modulating activity in these two brain regions could significantly improve cognitive functions during sports fatigue.

Recent research has demonstrated that tDCS improves fatigue resistance. An anodal tDCS session targeting the M1 or DLPFC have been shown to enhance cycling duration before exhaustion onset [59, 60, 61]. Angius et al. [62] reported that dual-site anodal tDCS over the M1 enhanced corticospinal excitability as well as the time to task failure during cycling in healthy individuals. Pollastri et al. [63] reported an improvement in the cycling time-trial performance of elite cyclists when bilateral anodal tDCS was delivered over bilateral DLPFC. Upregulating the DLPFC through tDCS may decrease the cognitive effort needed for elite cyclists to maintain inhibitory control, thereby enabling them to generate greater power output for the same perceived exertion level [63]. In addition, Moreira et al. [64] described improvements in well-being and autonomic function in elite male soccer players following official matches through tDCS over the DLPFC, suggesting that tDCS can be an effective strategy to facilitate recovery in sports fatigue. However, the effect of tDCS on attention, decision-making, and working memory in elite soccer players during sports fatigue remains unclear.

Research has demonstrated the bilateral distribution of neural activation within the DLPFC [65]. Although earlier studies evaluated the effects of tDCS targeting the left DLPFC on cognitive function, recent research has found that the right DLPFC also plays an essential role [66, 67, 68, 69, 70]. Furthermore, imaging studies have demonstrated an association between cognitive functions and the right DLPFC [71, 72, 73]. The enhanced activation of the right PFC is related to enhanced conflict-driven cognitive control [72]. In addition, motor tasks (e.g., cycling) involving both the right and left legs suggest robust control by the contralateral hemisphere [63]. A study found that dual-site anodal tDCS applied to the M1, with cathodal electrodes positioned on the shoulders, enhanced corticospinal excitability and fatigue resistance [62]. Evidence has suggested that multi-site stimulation may augment the effects of tDCS [74]. Fischer et al. [74] found that, compared with a single-site tDCS applied to the M1, multi-site tDCS more than doubled cortical excitability. Multi-site tDCS might activate broad neural circuits due to its synergistic effects, potentially enhancing the tDCS effects [74]. The dual-site montage, with anode electrodes positioned over the target brain regions and cathodal electrodes on the shoulders, enables simultaneous stimulation of M1 or both DLPFCs. This extracephalic montage can minimize the impact of the cathodal electrodes on other brain areas [62]. Research shows that, compared with cephalic montages, extracephalic tDCS montages targeting the M1 might generate higher total current densities in deeper brain regions (e.g., white matter) and tend to produce greater average vertical current densities in both M1 and somatosensory cortices [75]. Given these potential advantages of dual-site tDCS, the present study investigated the effects of dual-site tDCS of the DLPFC and M1 on attention, decision-making, and working memory in elite soccer athletes during sports fatigue, hypothesizing that this intervention would improve these cognitive functions.

Twenty-three non-smoking elite soccer athletes (excluding goalkeepers) participated in this study (sex: eight females; age: 20.6

Heart rate (HR), rating of perceived exertion (RPE), and blood lactate (BLa) data were obtained using an HR monitor (V800, Polar Electro OY, Kempele, Finland), the Borg 6–20 RPE scale, and a lactate scout+ analyzer (EKF Lactate Scout, Magdeburg, Germany), respectively. HR and RPE were documented in the last five seconds per minute and upon completion of maximal incremental exercise protocol, and before and after cognitive performance assessments and tDCS interventions. BLa levels were determined from blood samples taken from the left fingertip immediately after exercise.

Successful induction of sports fatigue was ascertained when HR, RPE, and BLa met at least two of the three specific criteria: (i) HR within

Sports fatigue was induced by maximal incremental exercise. The maximal incremental exercise protocol was conducted using a cycle ergometer (Ergoline Ergoselect 100K, Ergoline, Bitz, Germany) with an appropriate saddle height and handlebar position. Time to exhaustion (TTE) was determined when participants were unable to sustain a rate of 60 revolutions per minute for more than 5 seconds. Peak power output (PPO) was defined as the maximum intensity that a participant maintained on the ergometer for over one minute.

Attention, decision-making, and working memory performance were assessed using the Stroop Color-Word task, the Iowa Gambling task, and the 2-back task, respectively. All tasks were performed using E-prime 3.0 software (Psychology Software Tools, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) on a 17-inch computer monitor.

The Stroop Color-Word task was presented on a black background. The stimuli were presented in the center of the screen and comprised four color names written in Chinese characters—i.e., 红 for red, 绿 for green, 蓝 for blue, and 黄 for yellow. Each stimulus had a font size of 2.5 cm and was viewed from a comfortable eye-to-monitor distance. The task included congruent, neutral, and incongruent trials. These trials were presented in equal numbers and randomized sequence. In the congruent condition, Chinese color words appeared in their corresponding color ink (e.g., the word “红” in red ink). In the neutral condition, a series of three “X”s appeared in one of the four colors. In the incongruent condition, color words were shown in colors different from their written meanings (e.g., the word “红” in green ink). Participants responded on a keyboard with four designated keys (D for red, F for green, J for blue, K for yellow), and the task was to press the corresponding color button both quickly and accurately. Participants conducted a practice block with 18 trials before formal expriment. Then, participants completed two expriment blocks,each consisting of 72 trials. Each word stimulus was displayed for 500 milliseconds, succeeded by a 2000 milliseconds interval. The accuracy and reaction time were recorded for this task.

The Iowa Gambling task stimuli comprised four card decks (A, B, C, and D) displayed against a white background. To minimize distractions and prevent strategy based on card appearance, the backs of the decks were standardized with a blue cover [79, 80]. Decks A and B were considered disadvantageous, as they yielded larger immediate gains of ¥100 yet leading to net losses over time. Deck A featured frequent but smaller losses compared to deck B. Specifically, every 10 cards from deck A resulted in five random penalties ranging from ¥150 to 350 (total loss, ¥1250), while every 10 cards from deck B led to a single large penalty of ¥1250. Ultimately, both decks A and B resulted in a net loss of ¥250 per 10 cards. Conversely, decks C and D were deemed advantageous, offering smaller, more consistent gains over time. Deck C included more frequent but smaller losses compared to deck D. Every card selected from decks C and D earned a gain of ¥50 , but every 10 cards in deck C came with five random penalties ranging from ¥25 to 75 (total loss, ¥250). Deck D incurred one penalty of ¥250 per 10 cards, leading to a net gain of ¥250.

The task structure included five blocks of 20 cards each, totaling 100 cards. The sequence of card presentation was randomized. Participants were provided with a virtual balance of ¥2000 and instructed to maximize earnings by selecting one card at a time from any deck. Selections were made using a mouse click within a four-second time window per card. If no selection was made within 3.5 seconds, the computer would randomly choose a card. The total balance and real-time feedback on money won or lost per card (e.g., won 50 and lost none, or won 100 and lost 1250) were displayed at the top of the screen. The task automatically concluded after the hundredth card was selected, not known in advance by the participants. The primary variable of interest was the net score calculated from deck A subtracted from deck D over the last 60 trials (i.e., blocks 3, 4, and 5) for each tDCS session [81]. The currency ¥ refers to Chinese Yuan (CNY). For reference, an approximate exchange rate of ¥7 = $1 USD was used.

Participants were positioned at a comfortable eye-to-monitor distance from a computer screen displaying black letters (A–J) against a white background in a pseudo-random sequence. The stimuli, measuring 1 cm in size, appeared centrally on the screen. Participants were tasked with rapidly and precisely identifying whether the same letter had appeared two items before. Participants indicated a match by pressing the “V” key and a non-match by pressing the “N” key. Each stimulus was displayed for 500 milliseconds, succeeded by a 1500 milliseconds interval. In this study, the 2-back task included a 24-trial practice block and two experimental blocks, each consisting of 70 trials. The trials were presented in a random sequence with a ratio of 1:2 for matches to mismatches. The behavioral measures for this task included hits (correctly recognized matches), misses (incorrectly recognized matches), reaction times, and index d’.

tDCS was administered using a dual channel battery-driven stimulator device (YINGCI TECHNOLOGY, Shenzhen, China) and was delivered through two anodal (size: 7

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Design of experiments. (A) Diagram of the research design. (B) The tDCS montages used for brain stimulation. M1, primary motor cortex; DLPFC, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; HR, heart rate; RPE, rating of perceived exertion; tDCS, transcranial direct current stimulation.

All participants were required to visit the laboratory three times, with each visit spaced at least one week apart. Prior to the experiment, participants were briefed about the experimental procedures and safety precautions, were familiarized with the testing protocols, and provided written informed consent. In addition, they were advised to avoid strenuous physical activity and alcohol consumption for at least 24 hours and caffeine intake for at 12 hours prior to each test session. Testing times, environmental conditions, and equipment settings were standardized across all sessions.

Each of the three visits involved sports fatigue induction through maximal incremental exercise, followed by one of three tDCS interventions: dual-site anodal tDCS over the M1, dual-site anodal tDCS over the DLPFC, and sham tDCS. The tDCS sessions were conducted at the same time each day, and their sequence was counterbalanced among participants. HR and RPE were continuously monitored during the experiments. BLa levels were measured immediately after the sports fatigue protocol. Subsequently, participants performed the Stroop Color-Word task, the Iowa Gambling task, and the 2-back task in a counterbalanced order. A schematic of the study design is depicted in Fig. 1A.

For physiological and perceptual measures, one-way repeated measures analyses of variance (ANOVAs) with the within-subjects factor session (dual-site anodal tDCS targeting the M1, dual-site anodal tDCS targeting the DLPFC, sham tDCS) were conducted for the dependent variables (HR, RPE, and BLa of exhaustion as well as TTE and PPO during the maximal incremental exercise). Two-way repeated measures ANOVAs with the within-subjects factor session (dual-site anodal tDCS over the M1, dual-site anodal tDCS over the DLPFC, sham tDCS) and time (rest, exhaustion, before tDCS, after tDCS, after cognitive task performance) were conducted for the dependent variables (HR and RPE).

For the Stroop Color-Word task, the mean reaction time for correct responses was analyzed for each condition within each tDCS session. Reaction times under 100 ms or those deviating over three standard deviations from the individual’s mean reaction time were excluded. The percentage of excluded data was

For the Iowa Gambling task, a two-way repeated measures ANOVA with the within-subjects factors session (dual-site anodal tDCS over the M1, dual-site anodal tDCS over the DLPFC, sham tDCS) and block (block 3, block 4, block 5) was conducted for the dependent variable net score.

For the 2-back task, the mean reaction time for correct responses was analyzed for each session. Reaction times under 100 ms or those deviating more than three standard deviations from the individual mean value were discarded. The percentage of excluded data was

Data normality was evaluated using the Shapiro–Wilk test. For the ANOVAs, sphericity was evaluated using the Mauchly test. If the sphericity assumption was violated, the degrees of freedom were adjusted using the Greenhouse–Geisser method. Significant effects and interactions were further explored using Fisher’s LSD posthoc test. The effect sizes were calculated using partial Eta Squared (

No adverse effects were reported either during or after tDCS sessions, aside from sensations of tingling and/or itching beneath the electrodes.

HR, RPE, and BLa at exhaustion, and TTE and PPO during the maximal incremental exercise protocol, showed no significant differences between dual-site anodal tDCS over M1, DLPFC, and sham tDCS (all p values

| Bilateral M1 | Bilateral DLPFC | Sham tDCS | F value | p value | |

| HR (bpm) | 167.3 | 168.7 | 169.2 | 0.688 | 0.508 |

| RPE (rate) | 18.7 | 18.7 | 18.7 | 0.078 | 0.881 |

| BLa (mmol/L) | 10.5 | 9.7 | 10.3 | 0.358 | 0.701 |

| TTE (min) | 10.5 | 10.6 | 10.6 | 0.317 | 0.730 |

| PPO (W) | 234.8 | 239.1 | 240.2 | 1.000 | 0.376 |

M1, primary motor cortex; DLPFC, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; HR, heart rate; RPE, rating of perceived exertion; BLa, blood lactate; tDCS, transcranial direct current stimulation; TTE, time to exhaustion; PPO, peak power output.

No significant differences were found in HR and RPE between the dual-site anodal tDCS over the M1, the DLPFC, and sham tDCS during the experimental procedures (all values of p

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. The results of the psycho-physiological measures. HR (A) and RPE (B) during the experimental procedures (Time1: rest; Time2: exhaustion; Time3: before tDCS; Time4: after tDCS, before cognitive performance; Time5: cognitive tasks). M1, primary motor cortex; DLPFC, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; HR, heart rate; RPE, rating of perceived exertion; tDCS, transcranial direct current stimulation. Error bars represent standard error (SEM).

For accuracy, the repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of condition (F1.408, 30.982 = 14.782, p

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Outcomes from various intervention sessions on Stroop task accuracy. M1, primary motor cortex; DLPFC, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; tDCS, transcranial direct current stimulation. * Statistically significant at p

For reaction time, the repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of condition (F2, 44 = 54.370, p

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Outcomes from various intervention sessions on reaction time in the Stroop task. M1, primary motor cortex; DLPFC, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; tDCS, transcranial direct current stimulation. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean (SEM).

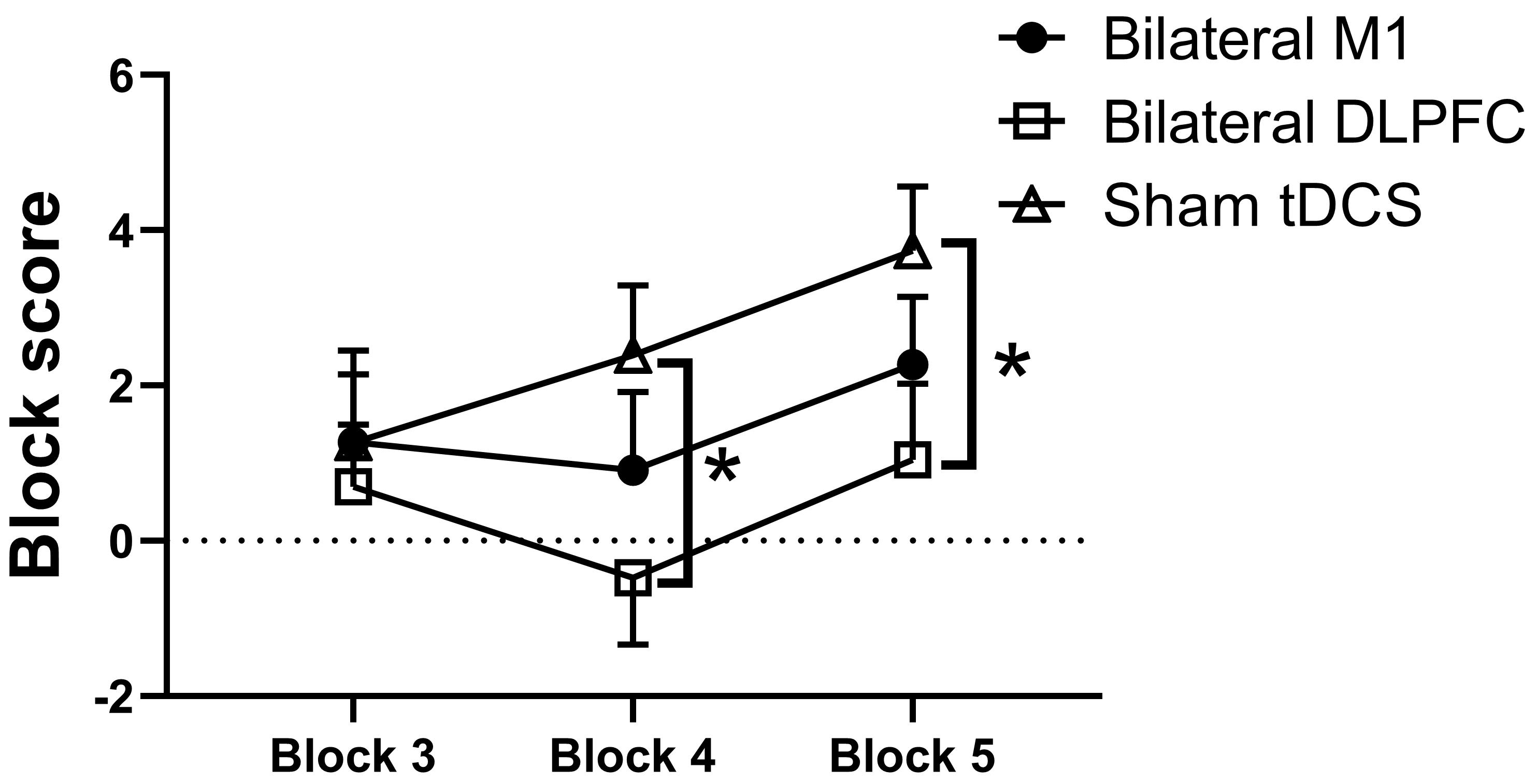

The repeated measures ANOVA revealed a marginally significant main effect of session for net score (F2, 44 = 3.207, p = 0.05,

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. Outcomes from various intervention sessions on the net score in the IGT. M1, primary motor cortex; DLPFC, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; tDCS, transcranial direct current stimulation. * Statistically significant at p

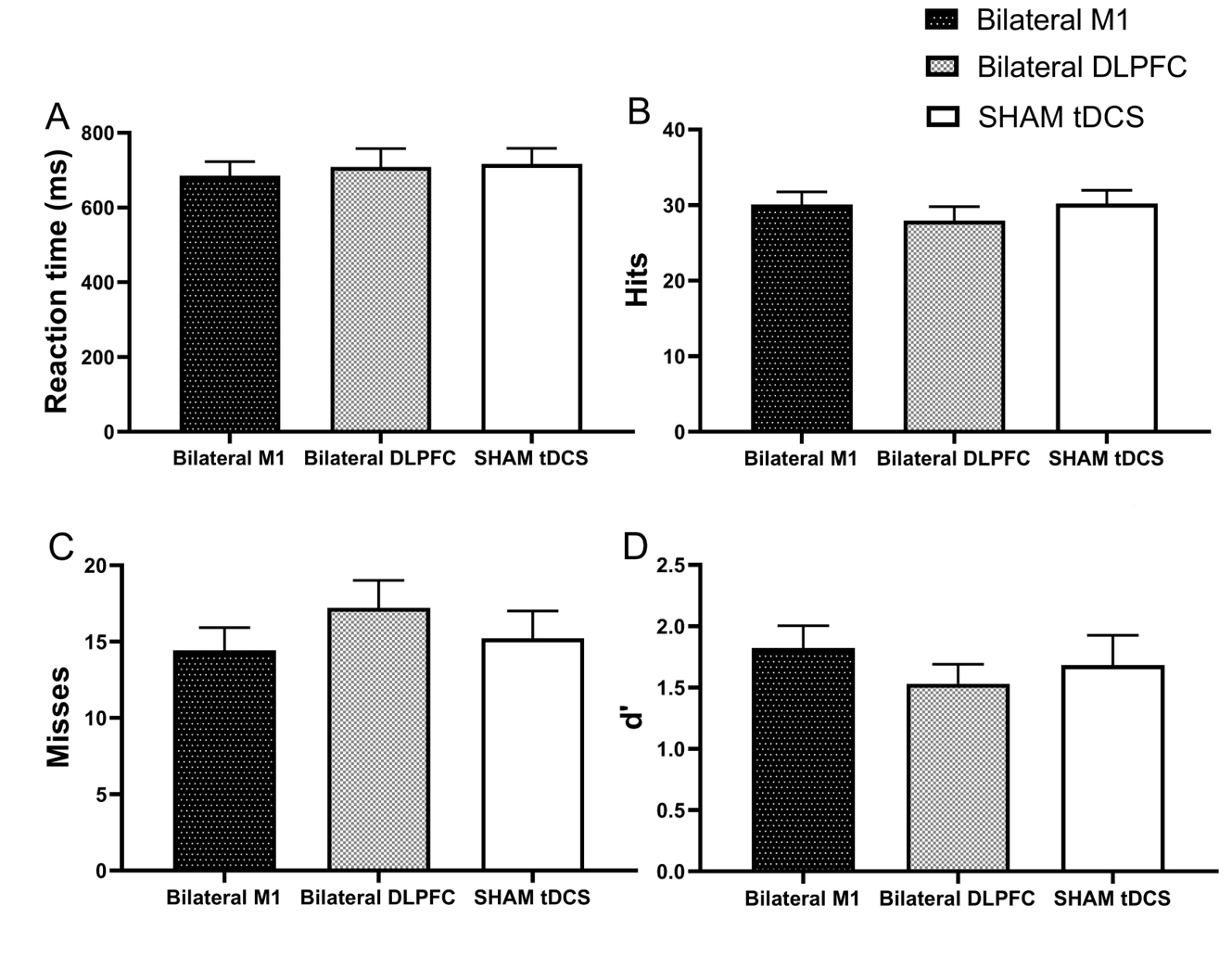

The repeated measures ANOVA revealed no significant main effect of sessions for reaction time (F2, 44 = 0.247, p = 0.782,

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6. Outcomes from various intervention sessions for reaction time (A), hits (B), misses (C), and index d’ (D) in the 2-back task. M1, primary motor cortex; DLPFC, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; tDCS, transcranial direct current stimulation. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean (SEM).

The present study aimed to assess the effect of dual-site tDCS applied to the M1 or DLPFC on attention, decision-making, and working memory in elite soccer players during sports fatigue. Dual-site tDCS applied to the M1 enhanced attention performance as demonstrated by improved Stroop Color-Word task performance during sports fatigue, whereas tDCS applied to the DLPFC did not. For decision-making, contrary to our hypotheses, dual-site tDCS applied to the DLPFC increased risk propensity in decision-making, as revealed by performance on the Iowa Gambling task during sports fatigue. However, dual-site tDCS applied to the M1 did not modulate the risk-taking in this decision-making task during sports fatigue. Dual-site tDCS targeting either the M1 or the DLPFC did not improve working memory performance.

The present study found that the dual-site tDCS over the M1 significantly enhanced attention performance, as shown by improved accuracy in the incongruent condition of the Stroop Color-Word task. This finding is consistent with previous research, where 2mA dual-site tDCS over the M1 for 13 minutes improved attention performance in experienced boxers [88]. M1 is the terminal pathway for voluntary movements, integrates inputs from cortical motor areas, sensory areas (e.g., PFC, basal ganglia, supplementary motor areas), and the midbrain, and projects to lower motor neurons in the spinal cord, connecting with various brain regions through afferent and efferent pathways [55]. During maximal physical exercise, fatigue-induced declines of force and electromyographic signals are correlated with reduced power in electroencephalographic frequencies related to motor cortical signals [89, 90], and functional magnetic resonance data show decreased interhemispheric functional connectivity between the contralateral and ipsilateral M1 [91]. A previous study demonstrated that dual-site tDCS over the M1 increased corticospinal excitability and improved cycling time to task failure in recreationally active participants [62]. This might increase the excitability of the M1 and enhance interhemispheric connectivity between the contralateral and ipsilateral, which may have improved attention performance following sports fatigue in the current study. Huang et al. [92] found that tDCS over M1 not only increased repeated sprint cycling power output but also improved accuracy in the Stroop Color-Word task. The widespread changes in functional connectivity through dual-site tDCS over the M1, particularly in the primary and secondary motor cortices (including the dorsal premotor cortex and left supplementary motor area/pre-supplementary motor area) and in the PFC, may also contribute significantly to the enhancement of attention performance [93]. M1 is anatomically adjacent to the supplementary motor area (SMA), and its activation may influence activity within the SMA [92], and the SMA may collaborate with the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex to manage cognitive disruptions arising from conflicting conditions in the Stroop task [94, 95], potentially enhancing attention performance.

However, in contrast with some previous studies, the effects on attention of tDCS applied to the DLPFC were not replicated in the present study, consistent with findings from our previous study and other research [96, 97, 98]. Contrary to our findings, other research employing single-site tDCS targeting the DLPFC has demonstrated improvements in attention performance [60, 99]. These studies used a cephalic tDCS montage, positioning the return electrodes over the contralateral supraorbital area, which potentially engaged additional brain regions like the anterior cingulate cortex [60, 99]. The anterior cingulate cortex may be essential for enhancing attention performance more effectively than bilateral DLPFC activation. Improvements induced by the cephalic stimulation montage may result from the adjustment of the return electrode or the interplay between the target and reference areas [100]. The tasks used to assess attention could also have contributed to the heterogeneous results. One study observed that 1.5 mA single-site tDCS over the left DLPFC lasting 10 minutes enhanced attention performance [101] but used a different task to assess attention, in which targets were identified by numbers instead of colors, and distractors were letters, placing different demands on the DLPFC [101]. Additionally, a systematic review indicated that tDCS over the PFC influences multiple cognitive functions, complicating the precise assessment of its impact on specific cognitive functions [102]. While dual-site tDCS over the DLPFC may modulate various cognitive functions, including attention, the cognitive decline induced by maximal incremental exercise might lead to insignificant modulation of attention performance by tDCS. Supporting this, research has shown that tDCS over the DLPFC improves attention in a state-dependent manner, implying that the effects of tDCS depend on the baseline electrophysiological state prior to intervention [99]. Sports fatigue induced by maximal incremental exercise may deactivate the DLPFC, contributing to the null effect observed in our study. Nonetheless, these suggested mechanisms are speculative and require further exploration.

This study found that dual-site tDCS applied to the DLPFC increased the appetite for risk in decision-making during sports fatigue, while dual-site tDCS over M1 did not appear to alter decision-making performance. This was contrary to previous research results, in which tDCS over the DLPFC typically reduced risk appetite, leading participants to adopt more conservative strategies to avoid the risk of missing rewards [42, 103, 104, 105, 106]. Differences in stimulation montages might account for discrepancies between the current findings and those of previous studies. Research has shown that single-site anodal tDCS targeting the right DLPFC led to more conservative decision-making [41, 107]. The predominance of the right hemisphere may be needed for a conservative, risk-averse approach in decision-making processes [108]. A study utilizing low-frequency, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation to disrupt DLPFC activity in healthy adults found that suppressing activity in the right DLPFC significantly increased riskier decision-making behavior [109]. This effect was not observed with similar suppression in the left DLPFC, highlighting the role of the right DLPFC in inhibiting appealing but risky options [109]. This finding underscores the asymmetric role of the PFC in decision-making [109]. The left DLPFC also plays a pivotal role in decision-making. Research indicates that single-site cathodal tDCS targeting the left DLPFC leads to a conservative, risk-averse strategy, whereas single-site anodal tDCS on the same region increases its activation and leads to a riskier decision-making strategy [108, 110, 111]. Activating the left DLPFC may have interfered with the participants’ capacity to modify their actions in response to negative feedback or errors, leading to a tolerance for losses, particularly sequential ones [108]. The tDCS montage used in this study may have enhanced activation in the left DLPFC, thus disrupting right-hemisphere dominance. This interference potentially led to a propensity for riskier decision-making strategies.

Additionally, studies employing dual-site tDCS, with montages involving anodal tDCS targeting one DLPFC and cathodal targeting the opposite DLPFC, found that tDCS resulted in a conservative strategy, conflicting with the current study’s findings [42, 103, 104, 105, 106, 112]. These results seem to suggest that tDCS targeting the bilateral DLPFC (anodal on one side and cathodal on the opposite) can modulate decision-making, but only when montages effectively inhibit the neural activity of the contralateral DLPFC and enhance unilateral DLPFC neural activity, thereby reducing risk-taking behaviors [105]. The interhemispheric balance of DLPFC activity has been identified as crucial for decision-making behaviors [105]. Maintaining an equilibrium between the right and left DLPFC is essential to facilitate a conservative, risk-averse approach during decision-making tasks [108]. In the current study, sports fatigue induced by maximal incremental exercise potentially decreased DLPFC oxygenation. Although dual-site anodal tDCS targeting the DLPFC increased bilateral DLPFC excitability, it might lead to the overactivation of neuronal activity in the bilateral DLPFC and disrupt the balance needed for conservative decision-making, leading participants to engage in riskier strategies. Neuroimaging research has identified critical roles for the DLPFC and the orbitofrontal cortex, but not the M1, in human decision-making [113, 114, 115, 116, 117]. Therefore, it is not surprising that dual-site tDCS over the M1 did not enhance decision-making performance during sports fatigue in the current study. Although the M1 is primarily regarded as the central hub for motor-related decision-making [118], the task in this study involved cognitively-driven risky decision-making rather than motor-related decision-making. This distinction may also explain why dual-site tDCS targeting the M1 failed to enhance decision-making performance following sports fatigue in this study.

Contrary to our expectations, the current study found no enhancements in working memory performance after applying dual-site tDCS over either the DLPFC or M1. This finding diverges from previous research, which has reported that one session of tDCS over the prefrontal area improves working memory [119, 120, 121]. The absence of effects in our study might be attributed to the task’s difficulty [122]. There might be a ceiling effect in the 2-back task among elite soccer players, potentially restricting tDCS’ potential to enhance working memory performance [123, 124]. In addition, significant inter-individual variability in working memory performance was reported, with baseline working memory capacity significantly influencing tDCS effects [125, 126, 127, 128]. Specifically, studies focusing on using tDCS to modulate visual short-term memory have found that individuals with lower baseline short-term memory capacity experience more substantial improvements [127, 128]. Given that our study involved elite soccer athletes, who likely possess superior working memory performance, this could explain the lack of significant results. Furthermore, some meta-analyses have reported that the effect sizes for tDCS on working memory are minimal [44, 129, 130]. Teo et al. [131] demonstrated that online stimulation of tDCS targeting the DLPFC during working memory task performance improved reaction times in the 3-back task compared to sham-tDCS. Conversely, our study employed the 2-back task and offline stimulation that was administered prior to task execution. The effectiveness of anodal online tDCS relies on changes in membrane potential that enhance neuronal excitability and modify the processing of incoming signals [132]. In contrast, the sustained impact of offline tDCS is associated with changes in synaptic efficacy, affecting both gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-mediated and glutamatergic activities [132]. In addition, Yeh et al. [133] found that online tDCS targeting the PFC during a working memory task might improve the neuromodulation of the target area because of potential resonance effects compared to offline tDCS. Compared to offline tDCS, online tDCS might elicit a synergistic effect between endogenous neural activity and the induced electric fields, thus improving the stimulation effects [133]. The absence of notable outcomes in the current study could be explained by a 10-minute session of 2 mA offline tDCS not performing as well as online tDCS in enhancing working memory during sports exhaustion. Another study emphasized the importance of the interplay between task-related activity and modulation induced by tDCS, suggesting that the different task demands might influence its effectiveness [134]. The 2-back task used in the present study needed fewer cognitive resources than the 3-back task and only involved the updating ability, a subset of working memory. The timing of stimulation and the task demands should be considered in further studies. In addition, high-definition tDCS, a novel tDCS technique that uses smaller high-definition electrodes, has been found to provide more focal, precise, and long-lasting stimulation [135]. A recent study found that, compared to conventional and sham tDCS, high-definition tDCS over the M1 was associated with greater between-day motor skill retention in healthy young adults [136]. The study also found that only high-definition tDCS modulated intracortical circuits bidirectionally, influencing specific neuronal pathways to the M1 [136]. The question of whether this novel tDCS technique over DLPFC and M1 can improve cognitive control during sports fatigue in soccer players warrants further exploration in future research.

The present study has several limitations. First, the fatigue induction and cognitive assessments were conducted within a laboratory setting, potentially limiting ecological validity when compared to actual competitive scenarios. Additionally, cognitive assessments were not sport-specific in nature. Despite this limitation, the current findings have inspiring implications for real-world soccer matches. The improvements of cognitive control by tDCS could be beneficial during halftime and when key players are substituted. Halftime is a critical period for recovery of cognitive decline from sports fatigue and reactivation. Applying tDCS during this period may improve the cognitive control which has deteriorated from the first half. Similarly, for player substitutions, applying tDCS can revitalize their declined cognitive control in sports fatigue, thus enabling them to make optimal decision-making and attention focus. After training, applying tDCS may accelerate the recovery of cognitive decline induced by sports fatigue. The improvement of attention performance induced by tDCS can help players remain highly focused throughout the match, potentially leading to improved positional awareness and faster reactions to dynamic match situations. This study found that risk propensity was increased after tDCS. This may not necessarily be detrimental and may translate into players taking more chances in the game, such as attempting more shots or choosing aggressive, high-reward tactics and tactical creativity. This translation is especially useful when training and if the team needs to adopt a more offensive strategy to change the course of the match. Future studies should employ sport-specific tasks to induce fatigue and evaluate cognitive function to ascertain their relationship to real-world matches or training environments. Second, this study focused on the immediate effects of a single session of tDCS on cognitive functions during sports fatigue but did not address potential long-term effects. Future longitudinal studies should investigate the sustained effects of a single tDCS session and the effects of multiple tDCS sessions on cognitive functions during extended periods of sports fatigue. The effects of some novel tDCS protocols (e.g., the accelerating tDCS protocol) and timing of tDCS intervention (e.g., online tDCS) on cognitive function also need to be explored [137, 138]. Third, the lack of significant findings with respect to cognitive functions might suggest the influence of unexamined variables (e.g., neural and physiological markers). Therefore, employing neurophysiological instruments like (e.g., electroencephalography) is crucial to further investigate the potential effects of tDCS on fatigue and underlying neurological mechanisms.

This study offers preliminary evidence that dual-site anodal tDCS targeting the M1 improves attention performance and stimulation over the DLPFC increases risk propensity in decision-making during sports-related fatigue. However, dual-site anodal tDCS targeting either the M1 or the DLPFC did not significantly impact working memory during sports-related fatigue in elite soccer athletes. These findings are encouraging for the continued adcancement of tDCS interventions aiming at enhancing attention performance in elite soccer athletes during sports fatigue. This preliminary evidence also supports the exploration of non-invasive brain stimulation techniques in sports settings to optimize cognitive function in athletes with sports-related fatigue. Further studies are required to fully harness the capabilities of tDCS in sports-related applications.

Data that support the findings of this study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon a reasonable request.

FQ and YZ contributed to the conception and design. NZ and LY contributed to data collection and data extraction. TY, NZ, MAN and FQ contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data. TY, FQ and NZ drafted the paper. FQ, MAN, and TY revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Sport University (Approval No. 2020070H), and all of the participants provided signed informed consent.

Not applicable.

This study was funded by Humanities and Social Sciences Research Funds of the Ministry of Education of China (22YJCZH136), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2022QN011), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (University 2020016).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.