1 Neuroscience Department, University of Connecticut Health, School of Medicine, Institute for Systems Genomics, Farmington, CT 06030, USA

2 Center for Laser Microscopy, Institute of Physiology and Biochemistry ‘Jean Giaja’ , Faculty of Biology, University of Belgrade, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia

Abstract

In neuroscience, Ca2+ imaging is a prevalent technique used to infer neuronal electrical activity, often relying on optical signals recorded at low sampling rates (3 to 30 Hz) across multiple neurons simultaneously. This study investigated whether increasing the sampling rate preserves critical information that may be missed at slower acquisition speeds.

Primary neuronal cultures were prepared from the cortex of newborn pups. Neurons were loaded with Oregon Green BAPTA-1 AM (OGB1-AM) fluorescent indicator. Spontaneous neuronal activity was recorded at low (14 Hz) and high (500 Hz) sampling rates, and the same neurons (n = 269) were analyzed under both conditions. We compared optical signal amplitude, duration, and frequency.

Although recurring Ca2+ transients appeared visually similar at 14 Hz and 500 Hz, quantitative analysis revealed significantly faster rise times and shorter durations (half-widths) at the higher sampling rate. Small-amplitude Ca2+ transients, undetectable at 14 Hz, became evident at 500 Hz, particularly in the neuropil (putative dendrites and axons), but not in nearby cell bodies. Large Ca2+ transients exhibited greater amplitudes and faster temporal dynamics in dendrites compared with somas, potentially due to the higher surface-to-volume ratio of dendrites. In neurons bulk-loaded with OGB1-AM, cell nucleus-mediated signal distortions were observed in every neuron examined (n = 57). Specifically, two regions of interest (ROIs) on different segments of the same cell body displayed significantly different signal amplitudes and durations due to dye accumulation in the nucleus.

Our findings reveal that Ca2+ signal undersampling leads to three types of information loss: (1) distortion of rise times and durations for large-amplitude transients, (2) failure to detect small-amplitude transients in cell bodies, and (3) omission of small-amplitude transients in the neuropil.

Keywords

- intracellular calcium

- neuropil

- dendrites

- cell nucleus

- signal distortion

- wide-field imaging

- high-speed imaging

- CCD camera

Firing of an action potential (AP) often causes an influx of Ca2+ into the intracellular space. Via light-emitting Ca-binding molecules, one is thus capable of detecting APs by measuring light fluctuations in neurons [1, 2, 3]. Due to its substantial optical signals, Ca imaging2+ is used to monitor brain activity, spanning spatial scales from synapses and dendrites to individual cells and circuits. Ca2+ imaging is often used in a wide-field fluorescence-based approach that combines good spatiotemporal resolution with large fields of view [4]. Through sustained expansion of fluorescent reporters for neuronal activity [5], and indicator expression strategies [6, 7], Ca2+ imaging analysis enables measurement and correlation of network dynamics with behavior [8]. One major feature of Ca2+ imaging is parallel recordings from many cells. Simultaneous registration of activity from multiple neurons improves the data robustness, and reduces the number of experimental trials required for obtaining significant differences between experimental groups. However, the number of recording sites is always in an indirect (inverted) proportion to the sampling rate. As the number of individual channels (neurons) increases, the sampling rate at which each channel (neuron) can be monitored decreases. What type of information is lost due to undersampling of optical Ca2+ transients? Before answering this question through experiments (Results section), we provide a brief overview of two popular Ca2+ imaging methods used in neuroscience.

In vivo two-photon calcium imaging is a method for registering neuronal activity in the brain of a living animal at the cellular or subcellular level. Main advantage of two-photon calcium imaging is high spatial resolution (

| Research Study | Sampling Rate | Selected Findings | |

| 1 | Heintz et al. (2022) | 6.07 Hz | Inhibitory microcircuits differently regulate the adaptation of pyramidal cells in the mouse visual cortex [18]. |

| 2 | Liu et al. (2023) | 10 Hz | Visual pathways transmit behaviorally relevant motion signals from selective visual areas to the brainstem, facilitating the plasticity of the optokinetic reflex behavior [16]. |

| 3 | Ren et al. (2022) | 28 Hz | During motor learning, acetylcholine regulates global and subtype-specific modulation of cortical inhibitory neurons [23]. |

| 4 | Allen et al. (2017) | 30 Hz | Local patterns of neocortical neuronal activity are globally coordinated [19]. |

| 5 | Liu et al. (2019) | 30 Hz | Different regions of the auditory cortex process sound onset and offset through parallel and spatially organized projections from the medial geniculate body, and are refined by specific intracortical connectivity [20]. |

| 6 | Tang et al. (2020) | 30 Hz | Layer 5 corticopontine neurons encode information related to sensory and motor tasks, and are crucial for task performance [17]. |

| 7 | Benisty et al. (2024) | 30 Hz | Correlations among neighboring neurons and between local and large-scale networks encode behavior [24]. |

| 8 | Ferguson et al. (2023) | 30 Hz | Interneurons that co-express vasoactive intestinal peptides participate in both state-dependent modulation of cortical activity and sensory context-dependent perceptual performance [25]. |

| 9 | Gasselin et al. (2021) | 30 Hz | Cell-type-specific nicotinic input disinhibits mouse barrel cortex during active sensing [26]. |

| 10 | Musall et al. (2019) | 30.9 Hz | During cognition, animals engage in a diverse array of uninstructed movements that influence neural activity [15]. |

| 11 | Musall et al. (2023) | 30.9 Hz | Different pyramidal neuronal types exhibit functionally distinct, cortex-wide neural dynamics that shape perceptual decisions [21]. |

| 12 | Keller et al. (2020) | 8–40 Hz | In the primary visual cortex, a canonical cortical disinhibitory circuit, consisting of inhibitory neurons producing vasoactive intestinal peptide and somatostatin, plays a role in contextual modulation [22]. |

| 13 | Korzhova et al. (2021) | 10 Hz | The neuronal network pathology seen in models of cerebral amyloidosis results from sustained aberrant activity in individual neurons [27]. |

| 14 | He et al. (2017) | 7.8 Hz | Sensory overactivity in the mouse model of fragile X syndrome is likely due to a defect in sensory adaptation within local neuronal networks [28]. |

Widefield calcium imaging is a practical method for measuring calcium activity across large brain regions in living animals using chemical indicators (Ca-sensitive dyes) or GECIs [11, 29]. The widefield approach was successfully employed for studying brain circuitry and neuronal networks [24, 30], cortex-wide activity in specific neuronal populations [19, 21], and neuronal Ca2+ signaling during behavior [31, 32, 33]. A key characteristic of widefield calcium imaging is its low temporal resolution [11, 34], with sampling frequency typically ranging between 10 and 30 Hz (see Table 2, Ref. [19, 21, 23, 24, 30, 31, 32, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39]). Two common approaches involve mesoscopic widefield imaging and widefield imaging using head-mounted systems [11, 33]. Mesoscopic widefield imaging uses a low-magnification objective, thus enabling registration from a field of view as large as 100 mm2 [21]. During imaging, the entire sample (brain) is exposed to the excitation light and the emission light is passed onto a high-sensitivity camera (Charged-Coupled Device (CCD), or Complementary Metal-Oxide Semiconductor (CMOS)) via a microscope. While typical camera resolutions encompass approximately 512

| Research Study | Sampling Rate | Selected Findings | |

| 1 | Benisty et al. (2024) | 10 Hz | Correlations among neighboring neurons and between local and large-scale networks encode behavior [24]. |

| 2 | Wang et al. (2024) | 10 Hz | Dynorphin peptidergic signaling in the prefrontal cortex suppresses defensive behavior by altering network states [31]. |

| 3 | Lohani et al. (2022) | 10 Hz | Functional reorganization of cortical networks, and fluctuations in behavior, use acetylcholine-mediated spatially-heterogeneous signals [36]. |

| 4 | Ishino et al. (2023) | 10 Hz | Adaptive and robust pursuit of uncertain reward to ultimately obtain more reward is enabled by the cooperation between the dopamine error signal and the reward prediction error signal [32]. |

| 5 | Smith et al. (2018) | 15 Hz | Structured long-range network correlations that guide the formation of visually evoked distributed functional networks, are established by local connections in early cortical circuits [30]. |

| 6 | Heiss et al. (2024) | 15 Hz | Lateral hypothalamus contains two distinct populations of CaMKII |

| 7 | Allen et al. (2017) | 15 Hz | Local patterns of activity in the cortex are globally coordinated [19]. |

| 8 | Piantadosi et al. (2024) | 20 Hz | Compulsive behavior is enhanced/promoted by hyperactivity of indirect pathway-projecting spiny projection neurons [37]. |

| 9 | Manning et al. (2023) | 20 Hz | Lateral orbitofrontal cortex has distinct roles in pathophysiology and treatment of different perseverative behaviors in obsessive-compulsive disorder [38]. |

| 10 | Ren et al. (2022) | 29.98 Hz | Acetylcholine regulates global and subtype-specific modulation of cortical inhibitory neurons during motor learning [23]. |

| 11 | Liu et al. (2021) | 29.98 Hz | During hippocampal sharp-wave ripples, hippocampus and large-scale cortical activity engage in selective and diverse interactions that support various cognitive functions [39]. |

| 12 | Musall et al. (2023) | 30 Hz | Different pyramidal neuronal types exhibit functionally distinct, cortex-wide neural dynamics that shape perceptual decisions [21]. |

Since Ca2+ transients are inherently slow, it is likely that Ca2+ imaging sessions using low optical sampling speeds in the range 3–30 Hz should capture the essence of Ca2+ signaling entirely. In this study, we investigate whether faster sampling speeds can capture valuable information that slower speeds might miss. To this end, we recorded spontaneous activity of neurons at two speeds, slow (14 Hz) and fast (500 Hz). Visual observations of recorded spontaneous Ca2+ signals did not indicate any significant differences between 14-Hz and 500-Hz recordings. However, quantitative analysis reveals that spontaneous calcium events recorded at 500 Hz had faster rise-times and their duration (half-width) has been significantly shorter in comparison to the 14 Hz data acquisition mode. At 500 Hz, we detected the presence of small-amplitude short-duration spontaneous Ca2+ events that were not detectable at 14 Hz. At 500 Hz sampling rate, these small-amplitude Ca2+ transients were particularly prominent in the neuropil composed of dendrites and axons, but were undetectable in the nearby cell bodies, despite both regions of interest (ROIs) being recorded at the same moment of time. Our study reveals that Ca2+ undersampling can distort the rise-time and duration of large-amplitude Ca2+ transients and prevent detection of small-amplitude Ca2+ transients in both the cell body and especially the neuropil. In summary, Ca2+ signal undersampling results in a three-fold loss of information: (1) severe distortions in the rise-time and duration of large-amplitude transients, (2) loss of small-amplitude transients in the cell body, and (3) loss of small-amplitude transients in the neuropil.

Primary neurons were isolated from the cortices of newborn pups (P0-P1) of C57BL/6 mice, which were anesthetized by hypothermia and decapitated. In brief, isolation of cortices was done in dissecting medium (DM) composed of HBSS without calcium and magnesium (Gibco™, cat. No. 14175079, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Grand Island, NY, USA), 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 0.02% (w/v) glucose, and 10 mM HEPES (Gibco™, cat. No. 15630-080, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Grand Island, NY, USA). After washing in DM three times, cortices were enzymatically digested at 37 °C in the water bath in 1 mg/mL trypsin in DM (freshly dissolved before this step; cat. No. T6567, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 20 min with occasional mixing. Loosened tissue was allowed to settle at the bottom of the tube, then rinsed three times in DM, followed by three washes in temperature-equilibrated plating medium (PM) composed of Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium/Nutrient Mixture F-12 (Gibco™, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA, cat. No: 11320033), 10% FBS, 0.02% (w/v) glucose, and 10 µg/mL gentamicin (cat. No. G1272-10ML, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Cortices were gently mechanically homogenized in 1 mL of PM using a 1000 µL pipette tip and incubated for 5 min at room temperature to allow larger pieces to settle on the bottom of the tube. Cells in the suspension (without larger tissue pieces) were counted and ~60,000 cells/well was plated onto 12 mm round glass coverslips (previously coated with poly-l-ornithine 50 µg/mL (cat. No. P4957-50ML, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA)) in 24-well plates. Two hours after plating the cells, the maintenance medium (MM) was added. MM was composed of BrainPhys Neuronal Medium (cat. No. 05790, Stemcell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada), 2% SM1 Neuronal Supplement (cat. No. 05711, Stemcell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada), 2 mM GlutaMAX (Gibco™, cat. No. 35050-061, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Grand Island, NY, USA), and 10 µg/mL gentamicin (cat. No. G1272-10ML, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Primary cortical neurons were grown in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2/95% air at 37 °C. Half of the medium was replaced with fresh MM 24 hours after isolation. On the third day after plating, half of the medium was replaced with fresh MM, enriched with cytosine

Neurons on glass coverslips were placed in the optical imaging chamber of an Olympus BX51WI microscope (SN OL56320, Olympus BX51WIF, Tokyo, Japan). The chamber was perfused with warm artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF; 34

Primary cortical neurons were loaded with OGB1 by patching with intracellular solution containing 25 µM of OGB1. The dye diffused freely into the cytoplasm, with good optical signals detected in the cell body within 10–15 minutes of whole-cell patching. Between 20 and 30 minutes after the whole-cell break-in, dendrites and axons were adequately filled with the fluorescent dye.

Manufacturer’s instructions were followed in the preparation of the OGB1-AM stock solution (Invitrogen, USA, cat. No: O6807). Primary cortical neurons were extracellularly loaded with 2.67 µM OGB1-AM for 20 min at 37 °C. After incubation, coverslips were placed in MM at 37 °C for 10 minutes to allow dye de-esterification, and removal of excess dye.

Coverslips with OGB1-AM-loaded neurons were transferred to the Olympus BX51WI microscope, perfused with oxygenated ACSF. The OGB-1 fluorophore was excited using a 470 nm light emitting diode, LED (pE, CoolLED, Andover, UK), excitation filter of 480/40 nm, dichroic filter of 510 nm, and emission filter of 535/50 nm. Max power of the LED illumination at 100% was 14 mW/mm2. Images projected onto an 80

Two primary criteria were used to select the experimental field of view. First, infrared differential interference contrast (IR-DIC) video microscopy was used to identify areas with groups of neurons displaying smooth, healthy membranes. Each field typically contained 8–23 neurons. Low-density regions on the coverslip were avoided. Second, neuronal spontaneous activity was monitored at a sampling rate of 14 Hz for three 15-second sweeps. If fewer than three cells were active during the 45-second (3

Optical traces were processed and analyzed using Neuroplex, Clampfit, and MATLAB software (Neuroplex: version 9.8.1, RedShirtImaging LLC, Decatur, GA, USA; Clampfit: Version 11.3.0.02, Molecular Device. LLC, San Hose, CA, USA; MATLAB Software: Version R2024a, MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA). The Neuroplex data acquisition and analysis software (version 9.8.1, RedShirtImaging, Decatur, GA, USA) was used for: (1) spatial averaging, (2) exponential subtraction, and (3) filtering. The values for the low-pass Gaussian filter and the high-pass RC filter are indicated in the figures. Averaged intensity of the region of interests (ROIs) containing neuronal cell bodies or neuropil were used in the analysis. Amplitudes of optical signals are expressed as

Unbiased selection of ROIs was conducted using an open-source software, EZcalcium [45]. EZcalcium v3.0.2 was downloaded from the GitHub site (https://github.com/porteralab/EZcalcium) and added to the MATLAB path. MATLAB 2024a Update 5 24.1.0.2653294 for Win64 was used. Automated ROI Detection option was used to detect ROI corresponding to individual neurons. Parameters for ROI Detection were kept the same for all analyzed fields of view. Using ROI Refinement option traces were extracted and “inferred” traces were used for the Ca2+ event parameter analysis. “Manual Analysis” refers to a manual selection of ROIs using a kernel function in Neuroplex, and export of optical traces. A custom-built Jupyter Lab routine was employed to accomplish three measurements: (1) number of Ca transients crossing the arbitrary threshold, (2) their peak amplitudes,

The depolarization of the neuronal membrane leads to the opening of Ca2+-permeable channels and consequent influx of Ca2+ ions. An increase in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration can be detected by optical recording [1]. This phenomenon has been widely utilized in numerous studies to monitor activity across multiple neurons simultaneously, using relatively low optical sampling rates, e.g., 3–30 Hz [8, 46, 47]. Although not always explicitly stated, the in vivo studies interpret Ca2+ imaging signals as indicative of AP firing. To investigate the nature of electrical signaling underlying neuronal Ca2+ transients, we performed simultaneous optical and electrical recordings in cultured neurons experiencing spontaneous activity. Neurons (n = 9) were loaded with the Ca2+-sensitive dye Oregon Green™ 488 BAPTA-1 (OGB1) via a patch pipette using the whole-cell configuration (Fig. 1A, image).

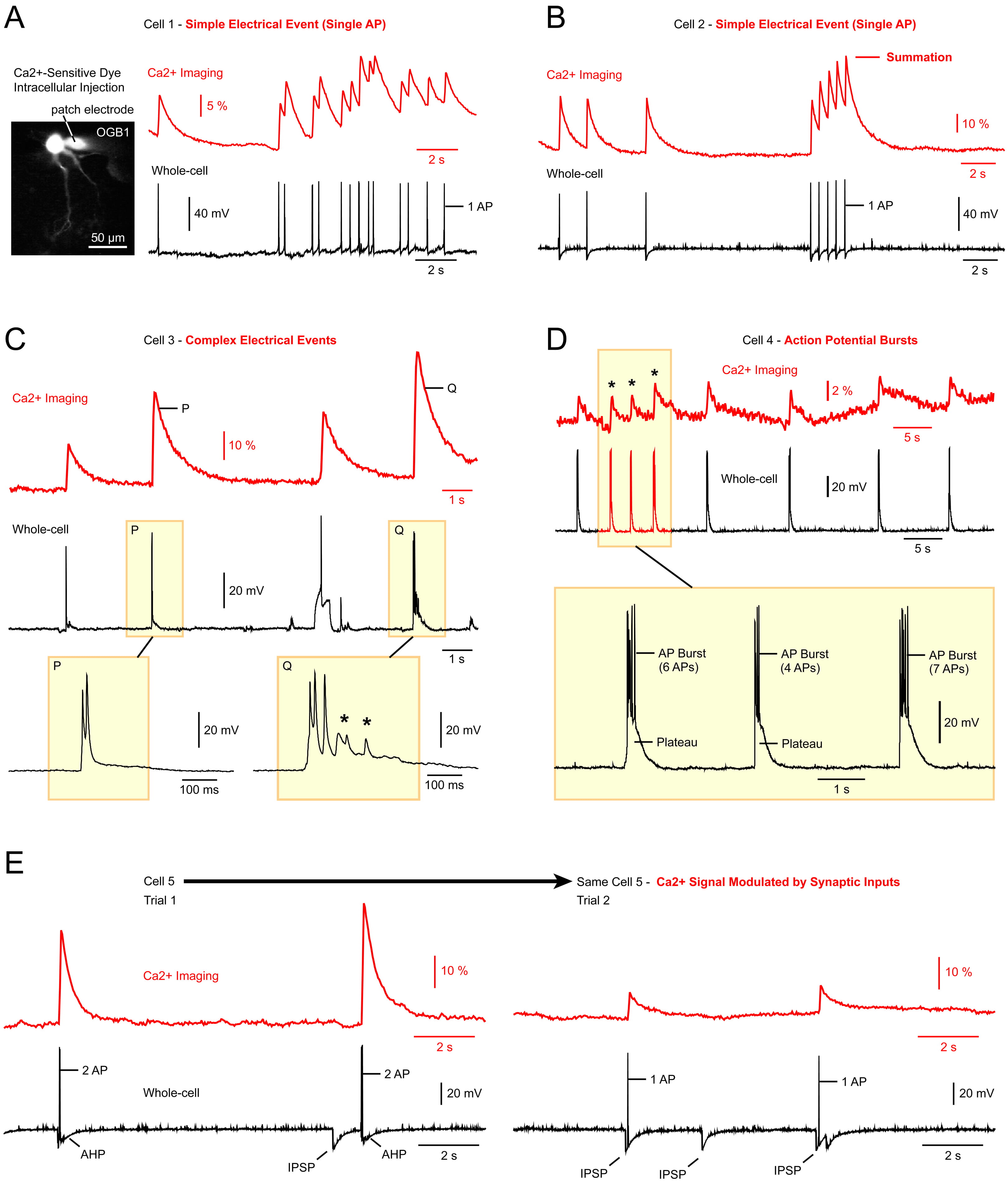

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Great variability of electrical signals underlying optical Ca2+ transients. Each panel (A–E) represents a dual electrical (sampling rate of 5 kHz) and optical recording (camera frame rate of 28 Hz) from a different neuron. (A) A cultured neuron was injected with a membrane impermeable Ca2+-sensitive dye, OGB1 (Oregon GreenTM 488, BAPTA-1). Spontaneous activity is then recorded in two ways: optically (red), and electrically (black trace). Simple electrical events (action potentials, APs) translate into optical signals where each peak marks the timing of an AP. The scale bar = 50µm. (B) Same experimental setup but a different cell. Reduced time intervals between APs cause temporal summation of Ca2+ transients. (C) Complex voltage waveforms (black) generate optical Ca2+ transients (red trace). If only optical data were available, it would be impossible to predict the type of electrical signaling (P and Q) behind each optical transient. (D) Simple Ca2+ transients suggest that each Ca2+ event was caused by an AP. However, patch electrode recording (whole-cell) revealed that each event is actually caused by a burst of APs (asterisk). Although the number of AP in the “AP burst”, and duration of the underlying “Plateau” potential, both vary significantly, this is not reliably reflected in the Ca2+ imaging data (red trace). (E) Two experimental trials obtained in the same cell, only seconds apart. In the second trial (Trial 2), a spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic potential (IPSP) reduces the optical signal amplitude. In the absence of a whole-cell recording, the Ca2+ imaging technique cannot determine if an AP was affected by: (i) synaptic input, (ii) neuromodulation, (iii) phototoxicity, or (iv) some other loss of cell’s integrity. Asterisks (*) indicate subtreshold activity. AP, action potential.

In the simplest scenario, commonly assumed by researchers employing in-vivo Ca2+ imaging technique, each AP corresponds to an individual Ca2+ transient observed in the optical trace (Fig. 1A, traces). It is well established that rapid AP firing causes Ca2+ transients to overlap and merge at their bases (Fig. 1B). As the AP train progresses, late spikes occur against an already elevated Ca2+ baseline, resulting in an increased amplitude of the optical signal. This effect arises from a gradually accumulating residual Ca2+, due to both a slow clearance rate from the cytosol and the slow OFF rate of the fluorescent indicator. Consequently, the optical Ca2+ transients exhibit summation in the recorded traces (Fig. 1B, summation). However, simple electrical events, in the form of individual APs void of any underlying significant depolarizations (Fig. 1A,B, whole-cell), are rare.

In many instances, neuronal electrical signaling is more intricate and not limited to simple AP firing. Instead, APs are interspersed with various other depolarizing signals. Such complex electrical waveforms were observed in every neuron examined (n = 9), clearly demonstrating that optical signals alone are insufficient to distinguish between different types of neuronal electrical activities. For instance, the optical transients labeled P and Q appear quite similar, yet the electrical “Q” event encompasses a significant amount of subthreshold activity (Fig. 1C, asterisks). Additionally, simple optical transients (Fig. 1D, red trace, asterisks) often result from complex AP bursts, with highly variable number of APs per burst (Fig. 1D, AP Burst), and plateau depolarizations at the base of the burst (Fig. 1D, Plateau). Furthermore, the amplitude of optical signals in Ca2+ imaging experiments offers limited insight, as it is frequently influenced by natural factors, such as synaptic inputs (Fig. 1E) and neuromodulation, as well as by artifacts including cell health, and variations in optical sensitivity.

In summary, interpreting Ca2+ imaging data is challenging without concurrent measurements of neuronal membrane potential (Fig. 1). We will next examine how the sampling rate influences the interpretation of Ca2+ traces.

Using a 40

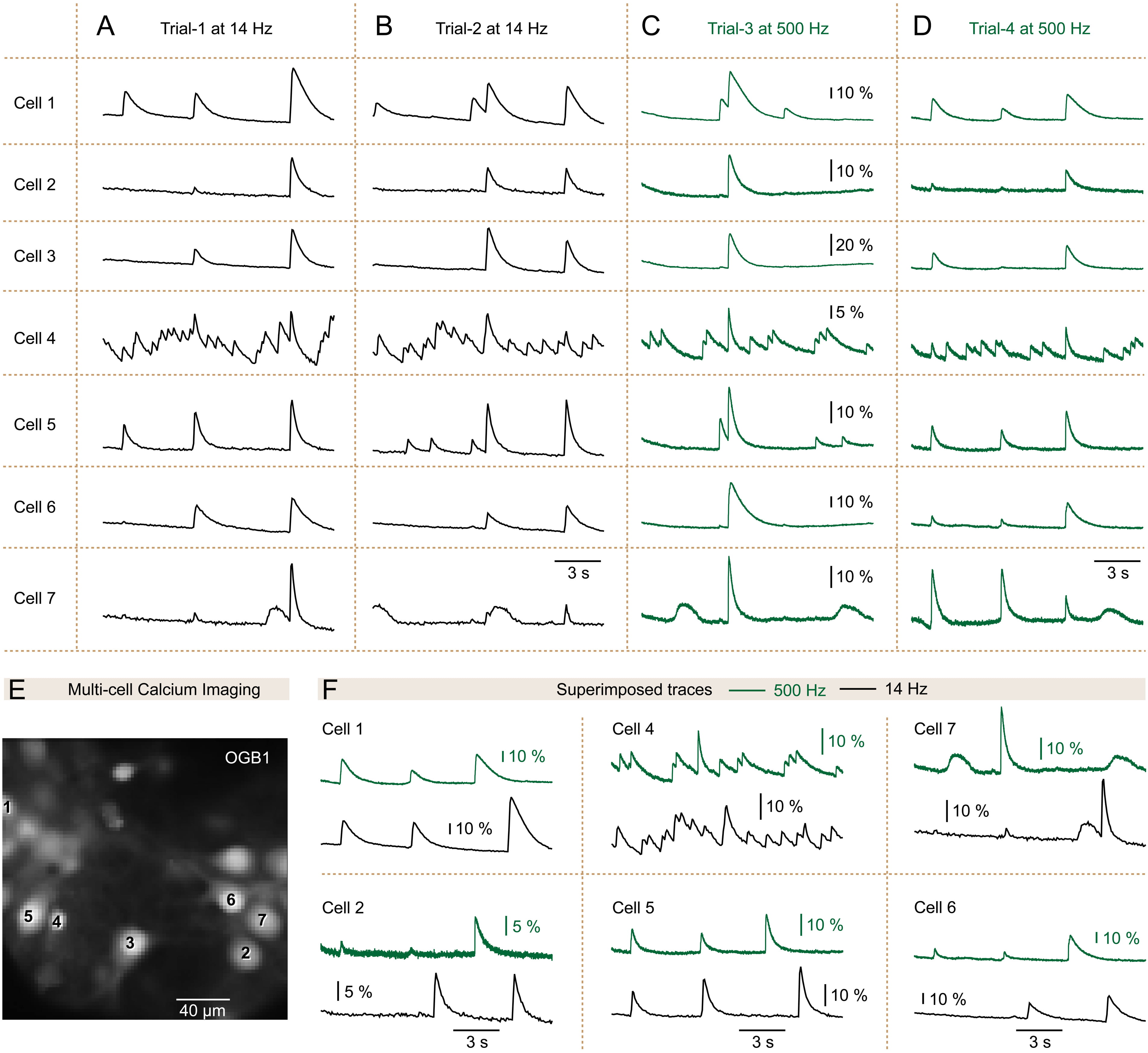

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Information about the optical Ca2+ transients is preserved with the 14 Hz-frame rate. Ca2+ imaging was conducted to observe the spontaneous activity of seven neurons (Cell 1 to Cell 7) across four experimental trials (from Trial-1 to Trial-4). (A) In Trial-1, a 72 ms sampling interval (sampling rate of 14 Hz) was utilized. (B) Similar to Trial-1, with the exception of a new recording trial captured 20 seconds later (Trial-2). (C) Identical to Trial-2, but with the sampling interval set to 2 ms (camera frame rate of 500 Hz). (D) Analogous to Trial-3, with another recording sweep taken 20 seconds later (Trial-4). (E) The field of view illustrates the neurons observed in Trials A–D. The scale bar = 40 µm. (F) Traces from the same cell are overlaid to compare Ca2+ transients captured at a 2 ms sampling rate (green) with those captured at a 72 ms sampling rate (black). OGB1, Oregon Green™ 488, BAPTA-1.

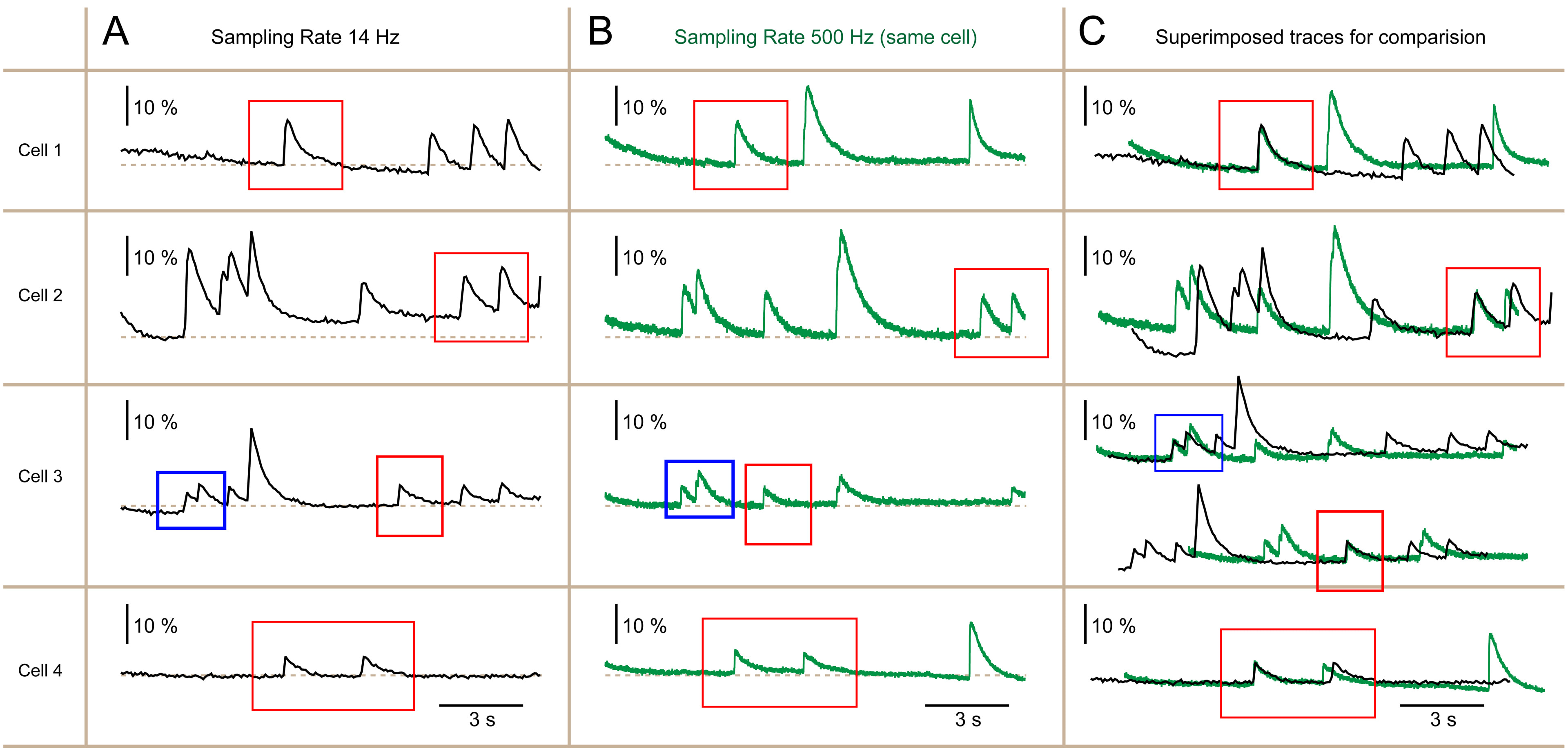

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Information about Ca2+ transients is preserved with the 14 Hz frame rate. (A) Ca2+ imaging was conducted to observe the spontaneous activity in four neurons simultaneously, employing a sampling rate of 14 Hz. (B) Similar to Panel A, apart from a new recording sweep taken approximately 20 seconds later, utilizing a faster sampling rate of 500 Hz. (C) Traces originating from the same cell are extracted from (A,B) and overlaid in (C) to compare Ca2+ transients captured at 500 Hz (depicted in green) with those captured at 14 Hz (depicted in black) sampling rates. Red and blue boxes highlight physiological events demonstrating nearly identical temporal dynamics at two distinct sampling rates.

Six out of the 269 neurons recorded for 60 seconds total, did not show any spontaneous Ca2+ transients. In the remaining 263 neurons, we identified at least 39 neurons with very similar waveforms at both sampling rates (Figs. 2,3). Visual inspection concluded that in a sizable number of spontaneously active neurons loaded with high-affinity Ca2+ indicator OGB1-AM (Kd ~0.2 µM), undersampling of Ca2+ optical signals causes minimal loss of information.

Two factors may be responsible for this result: (1) slow dynamics of the Ca2+ indicator, and (2) slow biological signals underlying the observed Ca2+ transients. (1) With low-affinity Ca2+ indicators (Kd

Why opt for a slower rate? Opting for a slower rate offers several advantages. Firstly, it places less strain on the imaging system, resulting in fewer instances of computer crashes and smaller data file sizes. More significantly, it reduces strain on neurons within the FOV. With 20 times less intense illumination, there is a corresponding 20-fold reduction in photodamage.

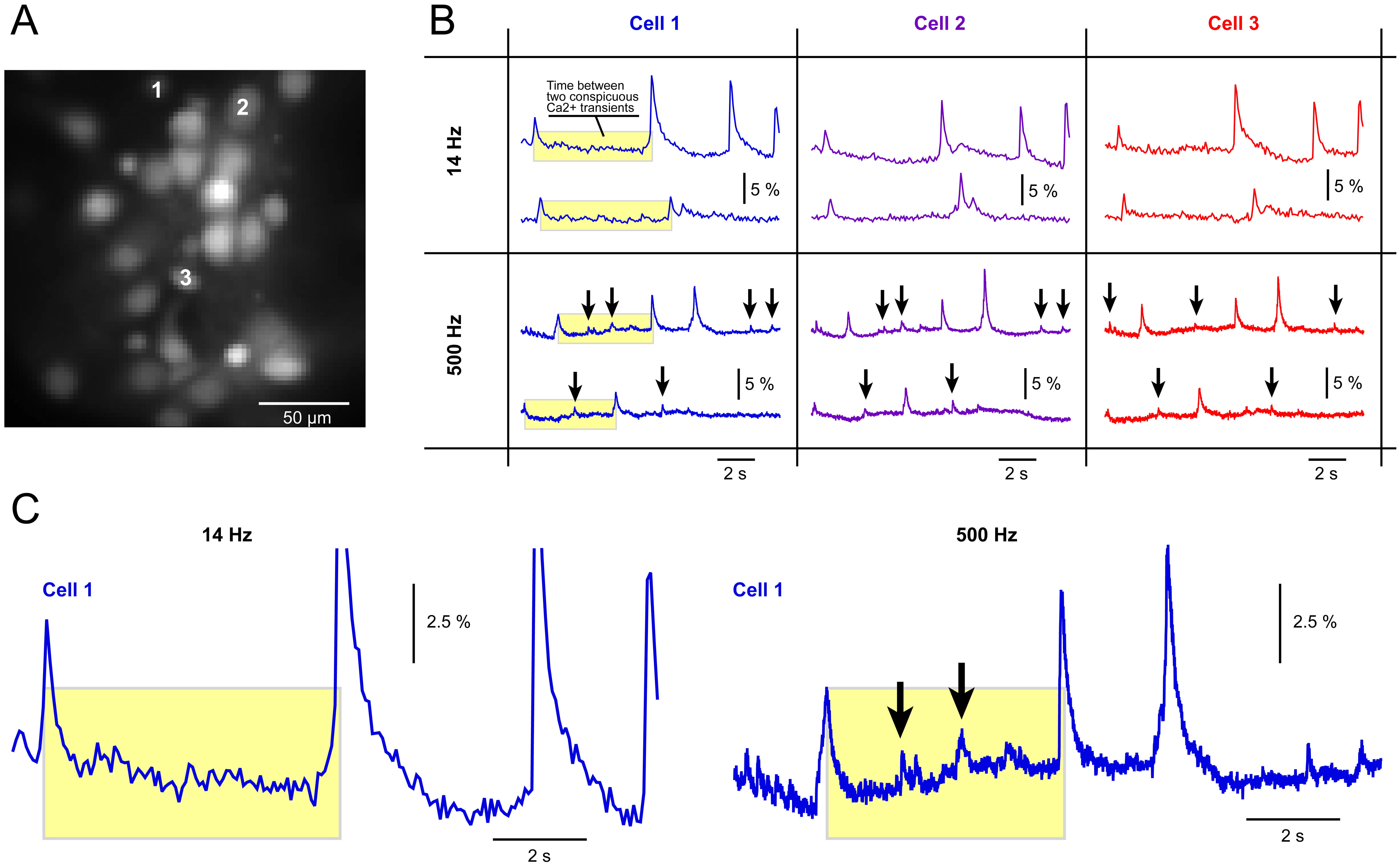

Our data suggested that large-size long-duration Ca2+ transients exhibit similar waveforms when recorded at either 14 Hz or 500 Hz (Figs. 2,3). If large and slow transients are captured equally-well at both sampling rates, there is a possibility that faster transients are not captured by the slower rate. We shifted our attention from large and slow transients to small-amplitude, short-duration Ca2+ transients. Between two consecutive Ca2+ signals (Fig. 4B, yellow rectangle) we detected small-amplitude transients, barely emerging above the baseline noise (Fig. 4C, arrows). For display in Fig. 4B, we selected 3 non-neighboring neurons (Cells 1–3, Fig. 4A,B), each providing evidence that small-amplitude short-duration Ca2+ transients are discernible in 500 Hz recording sessions (Fig. 4B, arrows), but not easily discernible with the 14 Hz sampling rate. We examined 16 multi-cell recording sessions obtained at both sampling rates. In these sessions, we found 83 neurons in which small and sharp Ca2+ optical signals appeared at 500 Hz but could not be discerned at the 14 Hz sampling speed.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Small-amplitude short-duration Ca2+ transients require a faster sampling rate. (A) Primary neurons bulk-loaded with a Ca2+ sensitive dye OGB1-AM and projected onto a fast CCD camera. The scale bar = 50 µm. (B) Optical recordings of spontaneous Ca2+ activity from three cell bodies (soma). In each cell, two recordings were first captured at 14 Hz, then followed by two traces captured at 500 Hz sampling rate. Arrows mark small and narrow Ca2+ transients, which are poorly represented in traces obtained at 14 Hz. (C) Two traces from B are shown here on an expanded time scale. CCD, Charged-Coupled Device.

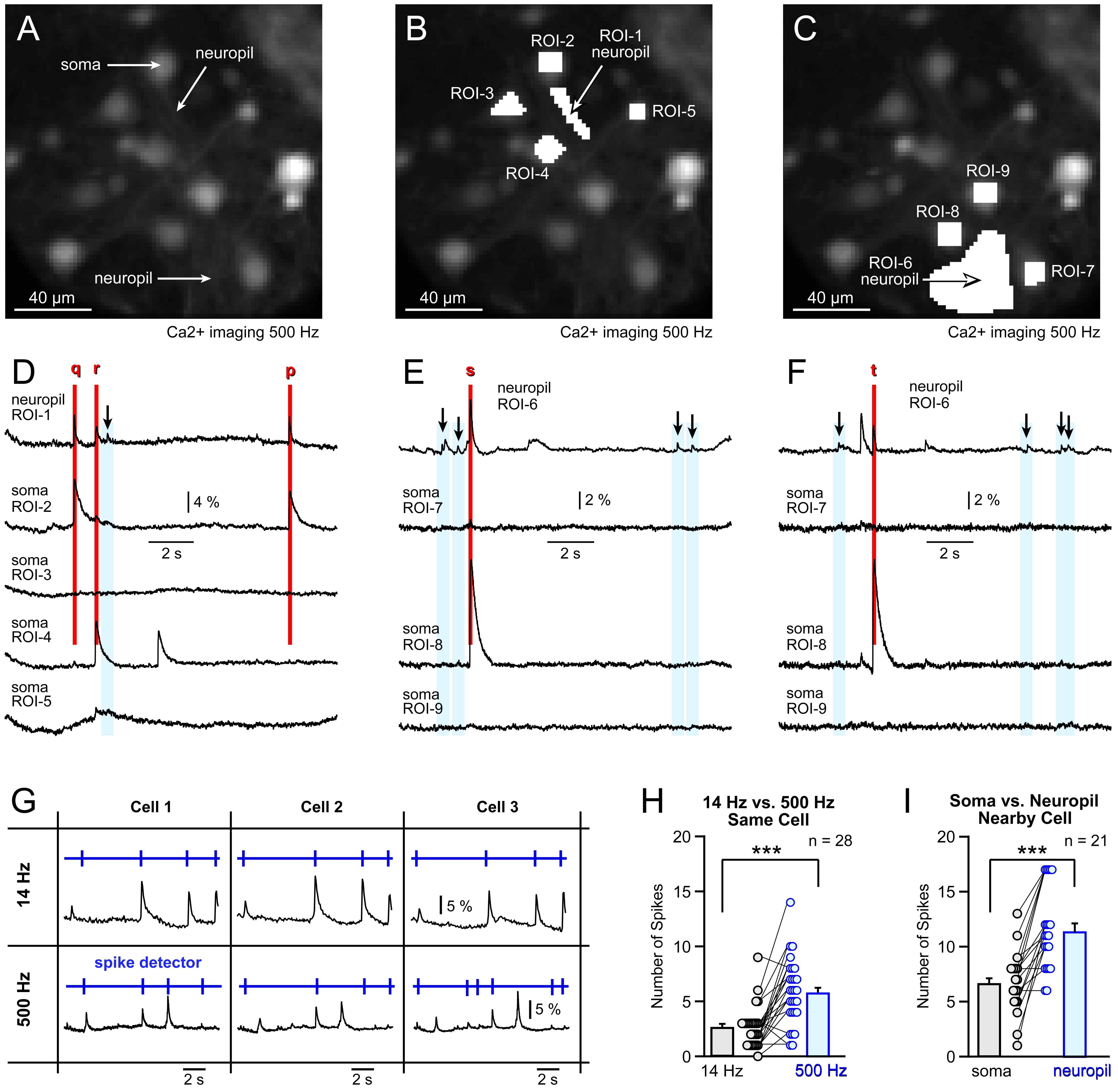

Unexpectedly, we found that ROIs positioned over a visual field areas involving dendrites and axons (neuropil) produced more frequent small and sharp Ca2+ events compared to ROIs selected on the cell bodies (somata) of neighboring neurons (Fig. 5A). In the illustrative example, one ROI (ROI-1) was selected on the neuropil, while four ROIs (ROI-2 to ROI-5) were positioned on the cell bodies of the neurons surrounding the neuropil (Fig. 5B). The idea was that electrical transients in one of these neurons might propagate into the neuropil, allowing the optical signatures of the same electrical event to be recorded in two places simultaneously.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. Small and fast Ca2+ transients are more often found in the neuropil. (A) Primary neurons bulk-loaded with a Ca2+ sensitive dye OGB1-AM and projected onto a fast CCD camera at 500 Hz frame rate. Neuronal cell body (soma) and two sections rich with neuropil (dendrites & axons) are marked by labels. (B) Region of interest (ROI-1) is selected in the area with no neuronal cell bodies, where dendrites and axons (neuropil) are the only Ca2+ signal-producing structures. On the other hand, the ROIs 2–5 are selected over the neuronal cell bodies. (C) New ROIs are selected, with ROI-6 covering the neuropil, while ROIs 7–9 covering cell bodies of nearby neurons. The scale bar is 40 µm. (D) Optical signals from ROIs 1–5 marked in (B), reveal sharp Ca2+ transients in the neuropil. Arrows and blue rectangles mark sharp optical transients restricted to the neuropil only. (E) Optical signals from ROIs 6–9 marked in (C). The neuropil area (ROI-6) exhibits several sharp Ca2+ transients (arrows) which are not present in the cell bodies of the neighboring cells (ROIs 7, 8 and 9). (F) Multi-cell optical recording shown in the previous panel (E) was repeated 20 seconds later, using the same selection of ROIs. Again, sharp Ca2+ transients are enhanced in the neuropil area (ROI-6). (G) Detection of spikes using a threshold search function in Clampfit (cartoon illustration). (H) Spike count per 15-s-trace obtained in the same cell (same neuron) at two sampling frequencies. (I) Spike count per a 15 s-trace obtained in the neuropil versus the neighboring cell body, at 500 Hz optical sampling rate. *** indicate p

For example, propagating AP waveforms can be recorded both in the neurite and the cell body simultaneously [51]. Indeed, one of the cell bodies marked by ROI-2 exhibited simultaneous Ca2+ transients with the neuropil marked by ROI-1 (Fig. 5D, red vertical stripes “q” and “p”) suggesting that the mechanism behind this result is either: [i] an AP backpropagation (from soma into dendrite), [ii] orthodromic propagation (from soma into axon), or [iii] antidromic AP propagation. In each case [i–iii], one AP is “visible” in both soma and neurite [51]. Similarly, the cell body marked by ROI-4 exhibited simultaneous Ca2+ transients with the neuropil ROI-1 (Fig. 5D, red stripe “r”), and the cell body marked by ROI-8 exhibited simultaneous Ca2+ transients with the neuropil ROI-6 (Fig. 5E,F, green stripes “s” and “t”).

In addition to these large-amplitude Ca2+ events, we identified several small-amplitude short- duration Ca2+ signals that were exclusive to the neuropil. The Ca2+ signals obtained in the neuropil ROI-1 (Fig. 5B, ROI-1) contained small and sharp Ca2+ transients that were not discernible in the nearby cell bodies (ROI-2 to ROI-5) (Fig. 5D, arrows). Similarly, the Ca2+ signals obtained in the neuropil ROI-6 (Fig. 5C, ROI-6) contained small and sharp Ca2+ transients not discernible in the nearby cell bodies (ROI-7 to ROI-9) (Fig. 5E,F, arrows). Visual inspection of 16 multi-cell recording sessions at 500 Hz revealed 21 neuropil areas (neuropil ROIs) exhibiting small and sharp Ca2+ transients that were not discernible in simultaneous 500 Hz recordings from the nearby cell bodies (n = 21). We concluded that small and sharp Ca2+ transients are more common in the neuropil compared to the cell body.

We analyzed optical traces obtained from the same neuron at two sampling frequencies, 14 Hz and 500 Hz. Each trace in this analysis was extracted from the cell body (Soma ROI). Traces were exponentially subtracted and filtered (14 Hz recordings: High pass RC (0.1 Hz) Tau; 500 Hz recordings: Low pass Gaussian (44 Hz), High pass RC (0.1 Hz) Tau (10)). Exported traces were opened in Clampfit™ and Ca2+ transients (events) were counted manually (Fig. 5G, blue raster plot above the trace). In total, 29 pairs of dual-frequency recordings were analyzed in 4 different fields of view. A greater number of spikes was consistently detected at 500 Hz compared to 14 Hz in the cell bodies of 29 neurons (n = 29). This difference was statistically significant, as indicated by a paired t-test (p

We used 500 Hz traces to compare a neuropil ROI (e.g., ROI-1, ROI-6) with an adjacent soma ROI (e.g., ROI-2, ROI-3, ROI-4, etc.). Only the cell bodies in the closest proximity to the neuropil ROI were used in these tests (Fig. 5B,C). We identified 21 such “Neuropil-Soma” pairs of ROIs and included them in the numerical analysis (Fig. 5I, 500 Hz). ROIs corresponding to the neuropil and ROIs covering the surrounding cell bodies were selected using a spatial average of 57 pixels, covering an area of approximately 20

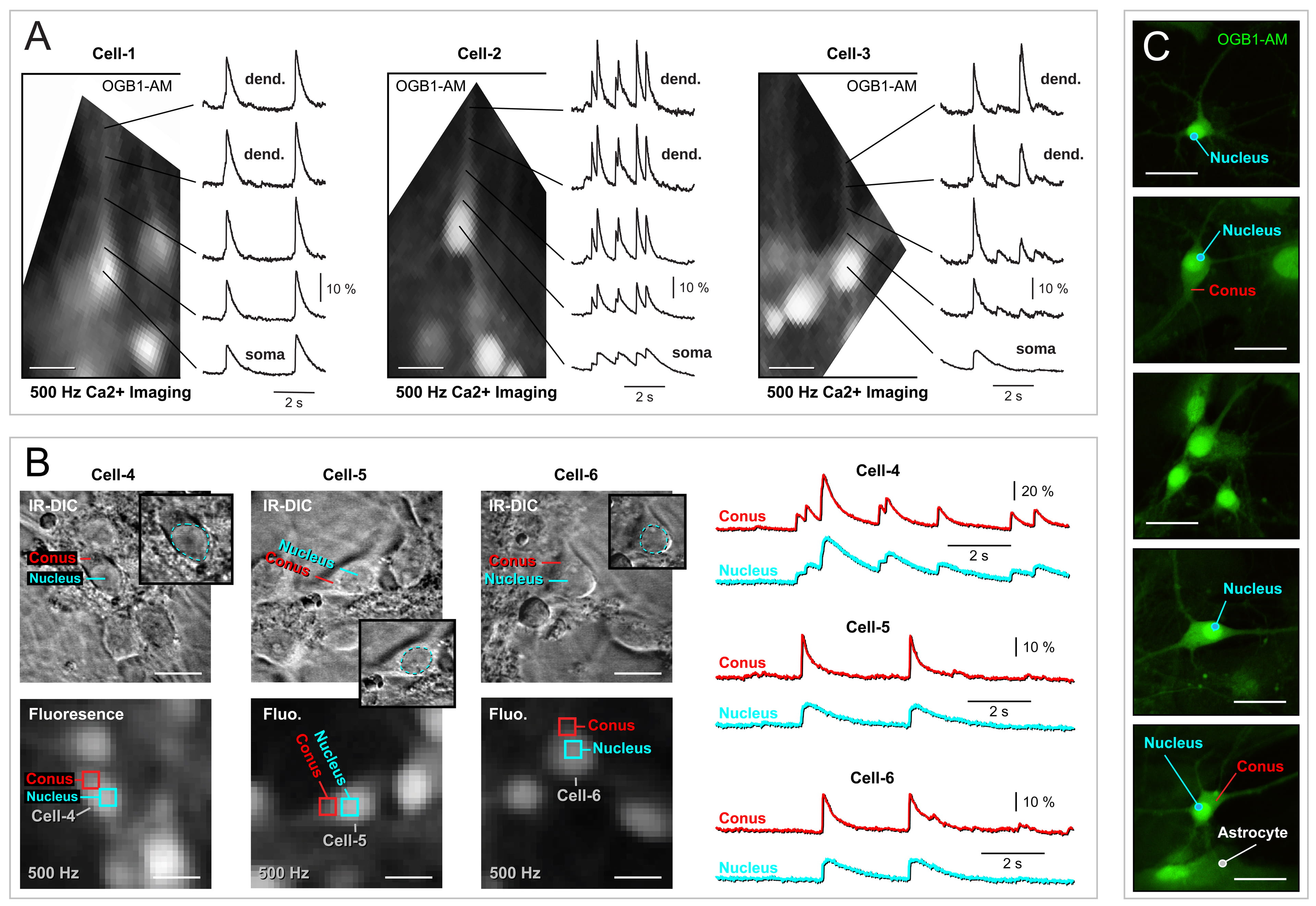

Ca2+ imaging allows real-time analysis of individual cells and subcellular compartments, such as dendrites [2]. We investigated spontaneous Ca2+ activity in dendrites of bulk-loaded neurons (OGB1-AM, Fig. 6). In visual fields recorded at 500 Hz (n = 14), we identified 10 cells with thick dendritic branches not obscured by neighboring cell bodies (Fig. 6A, Cells 1–3). In each of these neurons (10 out of 10), the dendritic optical signal exhibited greater amplitude and shorter duration than the corresponding somatic signal (Fig. 6A, compare optical traces “dend.” vs. “soma”).

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6. Spontaneous dendritic Ca2+ signals exhibit greater amplitude and faster dynamics. (A) Neurons were bulk-loaded with Ca2+ sensitive dye OGB1-AM. Optical recordings of the spontaneous neuronal activity were acquired at 500 Hz sampling rate. Five regions of interest along the dendrite-soma junction are displayed next to the image of the cell obtained with a fast, low-resolution CCD camera. Three cells were selected for display (Cell-1, Cell-2, and Cell-3). (B) Prior to Ca2+ imaging, neurons were photographed using IR-DIC. The round part of the cell body contains the nucleus, while the conical part of the cell body does not. The scale bar is 20 µm. The magnification of the small image is 40x objective. Below the IR-DIC image, we show the same area captured by a fast CCD camera with low resolution (80

Assuming that calcium influx and efflux occur only through calcium channels on the neuronal plasma membrane, and that these channels are uniformly distributed across various neuronal compartments (e.g., soma, dendrite), smaller compartments with a higher surface-to-volume ratio, such as dendrites, should exhibit larger calcium transients (greater amplitude) and higher calcium clearance rates (shorter half-width) than the cell bodies. However, the severe low-pass filtering of optical transients in the soma (Fig. 6A) suggests additional factors beyond the surface-to-volume ratio.

To further explore this, in the next series of experiments we recorded Ca2+ transients from two ROIs on opposite poles of the same cell body (Fig. 6B). One pole contained the cell nucleus (“Nucleus”), while the other pole, serving as a junction point to thick dendrites (presumably apical dendrites), had a conical shape (“Conus”) (Fig. 6B). Despite two ROIs being positioned on the same cell body, less than 5 micrometers apart, their corresponding optical signals showed vastly different Ca2+ waveforms (Fig. 6B, right panel). Invariably, the ROIs positioned on the rounded part of the cell body showed smaller amplitude (

High-resolution IR-DIC photographs confirmed the presence of the cell nucleus in the rounded soma portion (Fig. 6B, IR-DIC), but this did not explain the stronger fluorescence from one half of the cell body. Subsequently, we transferred glass coverslips with bulk-loaded neurons from the Ca2+ imaging station (Fig. 6B) to a confocal microscope with a 40

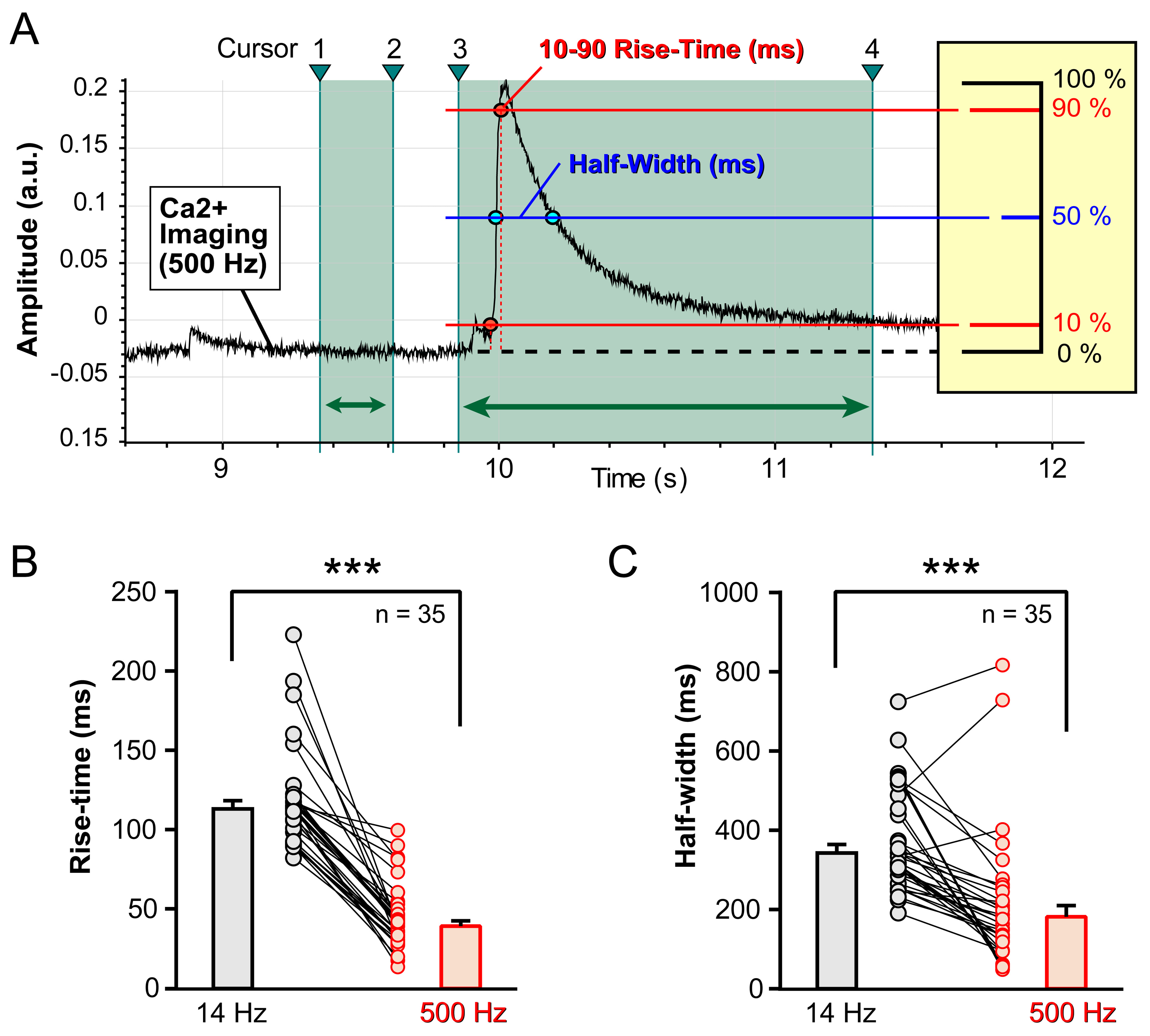

Numerical analysis was conducted on 35 neurons, where Ca2+ imaging sessions were performed at two distinct sampling rates. Each neuron’s spontaneous electrical activity was monitored optically through Ca2+ imaging, first at 14 Hz and then at 500 Hz, with no changes in cell position (X-Y) or focus (Z) between recordings. The rise-time of the optical signal, defined as the time taken to go from 10% to 90% of the maximum value, was quantified using Clampfit (Axon Instruments) (Fig. 7A).

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7. Rise-time and duration. (A) A Ca2+ imaging trace, imported into Clampfit for quantification of the 10–90 Rise-Time and Half-Width. The trace segment between Cursor-1 and Cursor-2 is used for calculation of the “baseline”. The trace segment between Cursor-3 and Cursor-4 is used for calculation of the “Rise-Time” and “Half-Width”. Rise-Time is defined as the period of time required for an optical signal to climb from 10% to 90% of the peak amplitude (100%). Half-Width is defined as the duration of time between two blue points selected at the intersection of the Ca2+ trace and the 50% amplitude level (blue horizontal line). (B) Spontaneous Ca2+ events sampled in the same cell, first at 14 Hz and then at 500 Hz (paired Student’s t-test, p

Contrary to our initial visual assessment, which suggested that large, long-duration Ca2+ transients had similar waveforms at both 14 Hz and 500 Hz (Figs. 2,3), numerical analysis revealed significant differences. Specifically, the Ca2+ signal rise-time was markedly shorter (faster) in traces obtained at the higher sampling rate. At 14 Hz, the mean rise-time was 113.35

Additionally, we quantified the duration of Ca2+ transients at half amplitude (half-width) (Fig. 7A). The half-widths of the Ca2+ signals also exhibited substantial differences between the two sampling rates. At 14 Hz, the mean half-width was 343.02

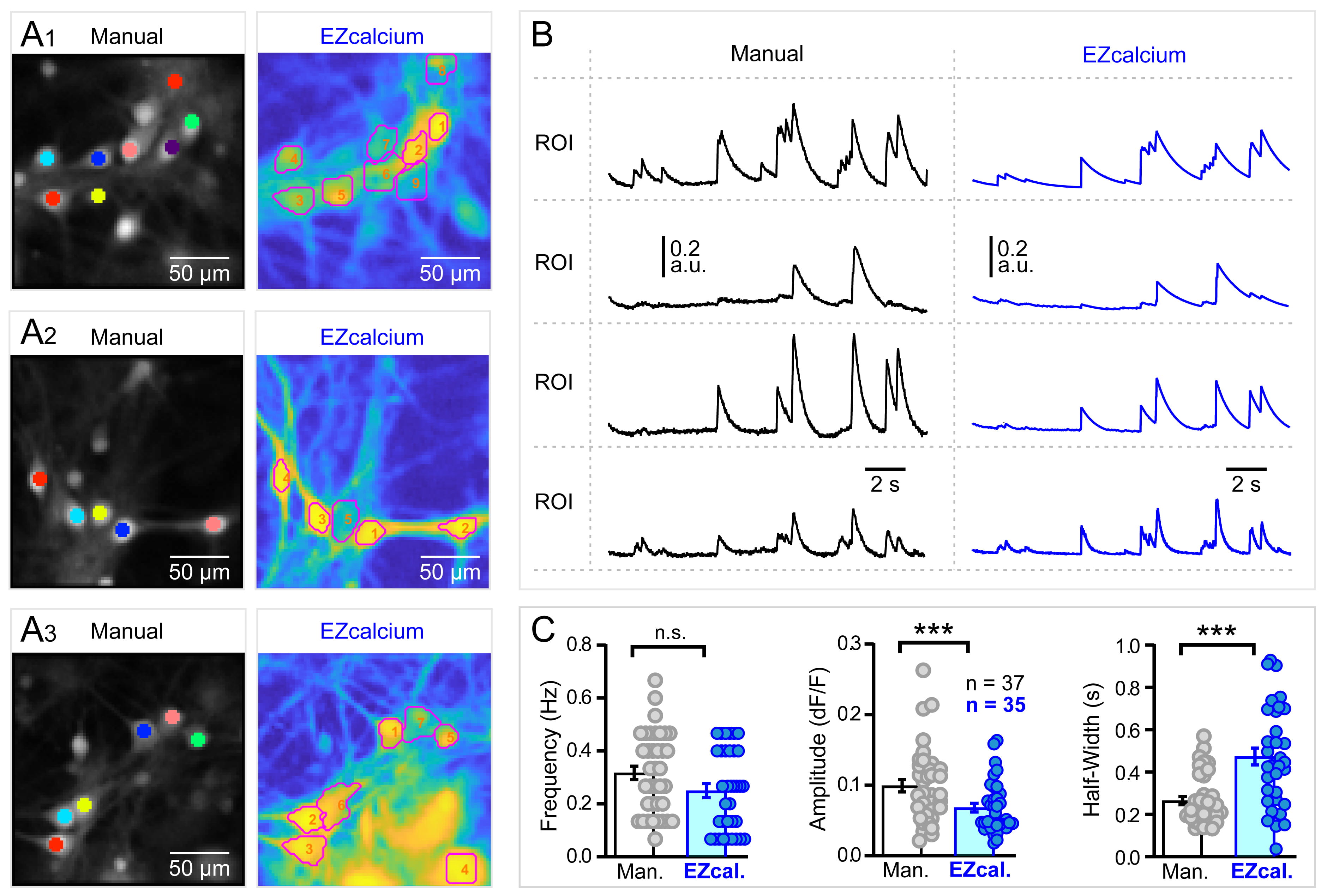

We utilized EZcalcium, an open-source software with an intuitive graphical user interface (GUI) [45], to perform consistent analysis of Ca2+ imaging data across different visual fields (Fig. 8A1–A3). The software facilitated the extraction of optical traces corresponding to putative individual neurons (Fig. 8B), which were subsequently analyzed using a custom Python routine in Jupyter Lab. This routine detected and quantified Ca2+ transients, measuring their frequency (in Hz or per sweep), peak amplitude (

Fig. 8.

Fig. 8. Unbiased processing of the 500 Hz Ca2+ imaging data. (A) A1–A3 represent three examples of the same data (500 Hz Ca2+ imaging) analyzed in two ways: using the Manual approach (Left Image) and using the software routine EZcalcium (Right image). Manual approach employed ROIs of identical shape and size (37 pixels). The EZcalcium approach generated ROIs of irregular shape. The scale bar is 50 µm. (B) Side by side comparison of optical traces obtained manually (black) versus EZcalcium (blue). The left column presents Ca2+ imaging traces from 4 regions of interest (ROIs) selected manually. The right column displays traces from the matching ROIs extracted using EZcalcium. The EZcalcium software reduces noise and determines the estimated timing of the Ca2+ transients (inferred). However, in this process, the optical signal amplitude appears reduced (compare black and blue traces). (C) We analyzed 4 experiments using both Manual and EZcalcium approaches. Each data point is one ROI. “n” – indicates the number of ROIs included in the analysis. From the same 4 fields of view (FOV), a similar number of spikes were detected using the two approaches (Frequency in Hz). From the same 4 FOVs, the EZcalcium approach assigned smaller amplitudes to the Ca2+ transients. The optical signal duration at half amplitude (Half-Width in ms) was significantly longer after processing of the optical data with the EZcalcium software. *** indicate p

Primary neurons in culture serve as a useful experimental system for studying fundamental concepts in neuroscience [52], investigating disease mechanism [53, 54]; and developing experimental strategies [55, 56, 57]. These neurons capture the essential elements of neuronal electrical signaling, primarily through excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs), inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (IPSPs) (Figs. 1E), and APs. After 10–12 days in culture, primary neurons develop membrane excitability sufficient to generate action potentials and form active synaptic connections [58]. A major advantage of cultured neurons is that they are capable of forming active synaptic connections and generating electrical activity without external stimulation [59, 60, 61]. This unprovoked (spontaneous) electrical activity, which is also a feature present in both developing and mature brains [62], was used to study the properties of optical signals in Ca2+ imaging sessions (Figs. 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8).

Fluorometric Ca2+ imaging is a sensitive method for monitoring neuronal activity [1, 63]. Neuronal Ca2+ transients are primarily driven by depolarizing electrical signals that activate voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, leading to Ca2+ influx [1]. These signals are crucial for elementary forms of neuronal communication, such as chemical synaptic transmission, and may be further amplified by Ca2+ release from intracellular Ca2+ stores [64, 65]. Thus, the amplitude of Ca2+ signals can be derived from three complementary sources: voltage-gated Ca2+ channels [2], Ca2+-permeable glutamate receptors [49], and release from internal Ca2+ stores [64, 65].

Ca2+-sensitive dyes are powerful tools for studying neural circuit dynamics at single-cell resolution [66]. In large-scale imaging applications, neuronal Ca2+ transients are often interpreted as APs, though the exact electrical signals associated with these transients are not always specified [8, 67, 68]. While bolus loading of membrane-permeable calcium indicators allows for the simultaneous monitoring of hundreds of neurons [63], the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) decreases in vivo due to fluorescence signal scattering by thick brain tissues, complicating single AP detection [69]. Additionally, the small surface-to-volume ratio in somatic compartments limits the detection of Ca2+ changes [69]. The likelihood of detecting a single AP in in vivo Ca2+ imaging is approximately 0.1 [68], while the detection rate for two successive APs could be 0.4, or lower. When optical recordings are paired with electrical recordings (e.g., whole cell) from the same neuron, then approximately 6 out of 10 events involving two consecutive APs in the electrical channel, resulted in no detectable changes in the Ca2+ imaging channel [68]. Interestingly, spikeless subthreshold depolarizations can sometimes generate detectable calcium transients [70, 71, 72].

Cells require a high surface to volume (STV) ratio to facilitate efficient chemical processes and the exchange of substances in and out of the cell. A higher STV ratio provides more surface area for substance exchange, typically resulting in a healthier cell. Smaller neuronal compartments have a greater STV ratio; for example, a dendritic branch has a higher STV ratio than the cell body. Several studies have found that during AP firing, calcium (Ca2+) signals are more pronounced in dendrites than in the cell body of the same neuron [2, 73]. Additionally, AP-evoked Ca2+ transients are more prominent in single boutons compared to other subcellular compartments of layer 2/3 pyramidal cells [74]. In Aplysia ganglion, Ca2+ dye bulk loading showed that the increase in fluorescence following spike activity was larger in the axon hillock (the cell body conus) than in the middle of the cell body [75]. The increased fluorescence in the axon hillock compared to the cell body following spike activity further highlights the importance of STV ratio in Ca2+ dynamics.

Smaller calcium transients evoked by single action potentials exhibit a mono-exponential decay. However, larger, and prolonged calcium transients, such as those evoked by trains of action potentials, display biphasic decay curves. Several mechanisms may account for this biphasic decay, including buffer non-linearities [76], calcium dependent regulation of calcium extrusion [77], intrinsic non-linearities in calcium transporters, and diffusion of calcium into adjacent compartments [74]. Although the precise mechanism remains unclear, its prevalence across various preparations and synapses suggests that biphasic decay is likely a physiological mechanism for calcium clearance following substantial Ca2+ influx.

A critical consideration in using chemical indicators like OGB1-AM is their accumulation in the cell nucleus, which can distort optical signal properties (Fig. 6A,B). The cell nucleus contains a nucleoplasmic reticulum capable of regulating Ca2+ fluctuations in localized subnuclear regions [78]. This intracellular machinery allows Ca2+ to simultaneously regulate various nuclear processes, linking neuronal activity to nuclear functions [78, 79]. However, nuclear accumulation of Ca2+ indicators can lead to a loss of dynamic Ca2+ signaling and, eventually, to programmed cell death [80, 81, 82]. In neurons expressing GCaMP variants via adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors, nuclear fluorescence can cause abnormal physiological responses, albeit without significant deficits in cortical circuits [3]. Dynamic Ca2+ signaling at the level of a neuronal nucleus has been shown to regulate the genetic program for neuroprotection and dendritic morphology [79, 83].

In the current study, we used a well-established approach of manual ROI selection, where ROIs are placed on the cell bodies of individual neurons [54, 84, 85]. However, selected ROIs, and even single pixels, can contain a complex mixture of signals from neuropil, neurons, glial cells, and noise [86] that contaminate optical traces. We found that ROIs placed over areas containing dendrites and axons (i.e., neuropil) more frequently detected small-amplitude short-duration Ca2+ events, compared to ROIs containing cell bodies (Fig. 5). Apart from being an informative parameter in physiological studies, the observed difference can potentially be used for training automated ROI extraction models [45]. Importantly, the detection of sharp Ca2+ events in the neuropil required a fast optical sampling rate of 500 Hz. At the lower sampling frequency (14 Hz), sharp Ca2+ events were not detectable in the neuropil. This finding may explain why in vivo studies with optical sampling rates below 50 Hz often miss distinct neuropil Ca2+ dynamics (Fig. 5). Furthermore, experimental approaches based on the AM-ester conjugated Ca2+ indicators (e.g., OGB1-AM), generally fail to highlight neuronal dendrites, or fine glial processes due to low contrast. These small structures do not stand out with sharp contrast and cannot be readily delineated by morphological filtering [86].

In single unit electrode recordings, the shape of an AP can be used to assign identities to neurons. Usually, such spike-sorting is based on the AP duration, where the fastest spikes come from inhibitory interneurons, and the slowest spikes are contributed by cortical pyramidal cells. However, Ca2+ activity waveforms do not provide strong signatures of individual cells’ identities because the Ca2+ optical signals are strongly dictated by intracellular Ca2+ buffering and the dye’s binding kinetics [87].

In Ca2+ imaging data, selected ROIs and even single pixels can contain complex mixtures of signals originating from target neurons, weakly labeled or out-of-focus cell bodies, neuropil, astrocytes, and noise. Significant crosstalk is particularly the case when imaging with low spatial resolution to improve temporal resolution (Fig. 5), or when constrained by the equipment for in vivo calcium imaging (Tables 1,2). Disentangling these signals without suffering crosstalk and finding the precise locations and shapes of individual neurons requires intensive demixing strategies [86, 88]. Demixing strategies for extraction of individual neurons from raw Ca2+ movies can be based on independent components analysis (ICA), non-negative matrix factorization (NMF), and constrained non-negative matrix factorization (CNMF). By using these demixing strategies, researchers can simultaneously infer the geometry and activity dynamics of specific neurons [45, 86, 88, 89, 90, 91].

Here, we used an open-source toolbox (EZcalcium) for analysis of Ca2+ imaging data (Fig. 8) based on CNMF to differentiate between changes in fluorescence intensity that correspond to biological Ca2+ signals and differentiate from noise [45]. The advantage of EZcalcium is its intuitive GUI and easy inspection of traces and ROI shapes. In the current study, the sets of ROIs recognized by the EZcalcium program were similar to the manually extracted ROIs (Fig. 8A1–A3,B). The numbers of Ca2+ transients detected through unbiased ROI selection (EZcalcium) were similar to those obtained through manual ROI selection (Fig. 8C, Frequency). However, two fundamental parameters of spontaneous signals (peak amplitude and duration) were significantly different between the two approaches (Fig. 8C, Amplitude, Half-Width). These findings underscore that neural activity properties inferred from multi-cell Ca2+imaging are highly dependent on the chosen event recovery methods, consistent with a previous study [92].

Our data reveal five distinct types of information that are easily lost in Ca2+ imaging studies due to optical undersampling. As expected, undersampling of large-amplitude Ca2+ transients leads to distortions in both (i) signal rise-time and (ii) signal duration (half-width). However, several unexpected consequences were also identified: (iii) failure to detect small-amplitude transients in cell bodies and (iv) omission of small-amplitude transients in the neuropil (axons and dendrites). Furthermore, we found that (v) including the cell nucleus within the region of interest (ROI) results in significant distortions of somatic Ca2+ transients. Specifically, two ROIs placed on the same cell body produced markedly different Ca2+ signals when one of the ROIs encompassed the nucleus.

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

SDA, PRA and KDM designed research. TNB, CAV, YMDZ maintained the mouse colony. KDM and VOI developed cultured neurons. KDM, VOI, CAV, YMDZ, and SDA performed calcium imaging. KDM, VOI, and SDA analyzed data. KDM, PRA, and SDA wrote the paper. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Euthanized mice were used for preparation of primary neuronal cultures, under the approval of the UConn Health Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), animal protocol (#200902).

We are grateful to John Glynn (UConn Health) and Chun Bleau (RedShirtImaging) and for technical support.

This research was funded by the Cure Alzheimer’s Fund (#65539), the National Institute of Mental Health (U01MH109091), the National Institute on Aging (AG064554), the UConn Health Alcohol Research Center (ARC)/Kasowitz Medical Research Fund (P50AA027055), UConn IBACS Seed Grant, the H2020-MSCA-RISE-2017 (# 778405), and Grant #4242 “NIMOCHIP” Science Fund RS.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.