1 Department of Hepatology, Federal University of Health Sciences of Porto Alegre (UFCSPA), 90050-170 Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul (RS), Brazil

2 Department of Nutrition, Centro Universitário CESUCA, 94935-630 Cachoeirinha, Rio Grande do Sul (RS), Brazil

Abstract

Mitochondria are organelles of eukaryotic cells delimited by two membranes and cristae that consume oxygen to produce adenosine triphosphate (ATP), and are involved in the synthesis of vital metabolites, calcium homeostasis, and cell death mechanisms. Strikingly, normal mitochondria function as an integration center between multiple conditions that determine neural cell homeostasis, whereas lesions that lead to mitochondrial dysfunction can desynchronize cellular functions, thus contributing to the pathophysiology of traumatic brain injury (TBI). In addition, TBI leads to impaired coupling of the mitochondrial electron transport system with oxidative phosphorylation that provides most of the energy needed to maintain vital functions, ionic homeostasis, and membrane potentials. Furthermore, mitochondrial metabolism produces signaling molecules such as reactive oxygen species (ROS), regulating calcium levels and controlling the expression profile of intrinsic pro-apoptotic effectors influenced by TBI. Hence, the set of these functions is widely referred to as ‘mitochondrial function’, although the complexity of the relationship between such components limits such a definition. In this review, we present mitochondria as a therapeutic target, focus on TBI, and discuss aspects of mitochondrial structure and function.

Keywords

- metabolism

- neurodegeneration

- head injury

Currently recognized as a significant public health issue, traumatic brain injury (TBI) often results in persistent neurological dysfunction [1, 2]. Classically, TBI is defined as an alteration of normal brain function caused by biomechanical forces resulting from rapid acceleration or deceleration of the brain, due to motorcycle or automobile accidents; impact from brain collision caused by falls, motorcycle or automobile accidents, or contact sports; pressure changes and air displacement due to explosions; and penetration of the brain by projectiles or objects [2, 3]. Also, literature classifies TBI as mild, moderate, or severe, potentially leading to premature death, cognitive alterations, and neuropsychiatric disorders, often compromising the quality of life of surviving individuals [1, 4]. This classification combines various criteria, with the Glasgow Coma Scale (using the best score within the first 24 hours) being the most commonly utilized qualitative tool [5]. Regarding translational research, researchers widely use the controlled cortical impact (CCI) model in mice to study pathophysiological mechanisms associated with TBI. The CCI model offers high reproducibility due to its ability to control injury induction parameters, targeting different severities of TBI [6].

In the central nervous system (CNS), normal mitochondria integrate multiple functions determining neural cell homeostasis. Hence, lesions that lead to mitochondrial dysfunction can desynchronize cellular functions, thus contributing to the pathophysiology of different brain disorders [7]. The brain has high rates of energy expenditure, and the coupling of the mitochondrial electron transport system with oxidative phosphorylation provides most of the energy needed to maintain functions such as neurotransmission, ionic homeostasis, and membrane potentials [8, 9]. Mitochondrial metabolism produces signaling molecules such as reactive oxygen species (ROS), regulates calcium levels, and controls the expression profile of intrinsic pro-apoptotic effectors. Researchers commonly refer to this set of functions as ‘mitochondrial function’, although such a definition is still limited by the complexity of the relationship between such components [10].

Moreover, studies have suggested that persistent neurometabolic changes may underlie the pathological features of chronic TBI. The initial pathophysiological changes resulting from primary mechanical damage can trigger secondary harmful effects, including progressive neurodegeneration [3]. More specifically, mitochondrial dysfunction and the production of ROS are well-documented outcomes of TBI, playing a pivotal role in the onset of neuroinflammation. Notably, inadequate oxidative capacity, mitochondrial swelling, and impairments in the electron transport system (ETS) characterize mitochondrial dysfunction, leading to increased formation of ROS and reduced energy production [11]. TBI triggers a cascade of events that can lead to neuronal death. Mitochondrial dysfunction is a key player in this process, initiating early and persisting for several days [11]. This dysfunction primes neurons for death due to the convergence of mitochondrial impairment and subsequent degenerative processes. As a result, mitochondria have emerged as a promising therapeutic target for improving functional outcomes in TBI [11, 12, 13]. This review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the mitochondrial mechanisms involved in CNS function and TBI. Additionally, we will discuss current mitochondria-targeted pharmacotherapies with potential applications for TBI patients.

Mitochondria are organelles of eukaryotic cells bounded by two membranes and cristae that consume oxygen to produce adenosine triphosphate (ATP), simultaneously synthesizing many vital metabolites, maintaining calcium homeostasis and regulating cell cycle mechanisms [7]. Long before its recognition as ‘the powerhouse of the cell’, Friedrich Gustav Jacob Henle, was the first to describe subcellular granules under various names, such as ‘plastochondria’ and ‘microsomes’, using light microscopy in 1841 [14]. Later, Richard Altmann [15], in 1890, claimed a similarity between bacteria and granular-looking organelles, suggesting that these were autonomous cellular components, called ‘bioblasts’: a state of chemical organization of matter that was larger than the molecule, but smaller than the cell, described as ‘the smallest morphological unit of organized material’. Consequently, Altmann proposed that bioblasts were once living cells that now lived inside eukaryotic cells. It was Carl Benda [16], in 1898, who named the mitochondria as ‘grain-like’ organelles - mitos (from the Greek, ‘thread’) and chondrion (from the Greek, ‘grains’), based on a tendency to form chains in grain shapes.

Mitochondria has two membranes: The outer membrane, which separates the organelle from the cytosol, and the inner membrane, surrounding the mitochondrial matrix, thus defining three different specialized regions [17]. The outer membrane separates the mitochondria from the cytosol, allowing the passage of metabolites through porins (POR) of the Voltage-Dependent Anion Channel (VDAC) and proteins that make up the family of Translocases of outer membrane (TOM) [18]. Further, outer membrane proteins regulate mitochondrial dynamics, mainly mitofusins 1 and 2 (Mfn1 and Mfn2) and mitochondrial fission protein 1 (FIS1) and proteins of the B-cell lymphoma-2 family (Bcl-2) such as Bcl-2 homologous antagonist killer (BAK). Also, outer membrane proteins interact with inner membrane proteins: the G alpha-q (G

The inner membrane delimits the intermembrane space (IM), structuring the mitochondrial cristae that separate the IM from the mitochondrial matrix [17]. Importantly, cristae are fundamental structures for mitochondria and not simple invaginations. In fact, tight tubular junctions regulated by different proteins separate cristae from the intermembrane space, forming specialized compartments to limit the diffusion of molecules important for the electron transport system and guarantee maximum functionality [22]. Namely, the inner membrane contains the proteins of the Translocases of the Inner Membrane (TIM) family, which transport proteins to the matrix, OPA1, MICOS, and cardiolipin (CL) interacting for the correct assembly and localization of inner membrane proteins. Specifically, G

Conceptually, mitochondrial oxidation of metabolic substrates in the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA) or the cytosol via malate-aspartate shuttles directs the flow of electrons from reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) and Reduced adenine flavin dinucleotide (FADH2) through the respiratory complexes to oxygen and concomitantly generates a hydrogen proton gradient and the synthesis of ATP. The inner membrane houses the components of the electron transport system: Complex I (NADH ubiquinone oxidoreductase or NADH dehydrogenase); Complex II (ubiquinone succinate oxidoreductase or succinate dehydrogenase); Complex III (ubiquinol-cytochrome C oxidoreductase); Complex IV (cytochrome C oxidase) where O2 consumption occurs and finally; Complex V, F1Fo ATP synthase, where ATP synthesis occurs. Super complexes organize the components of the electron transport system along the inner membrane (Fig. 1) and may present different sets of complexes (for example I, III, IV and V; II, III, IV and V; in addition to from the classic described from I to V), always notoriously converging to F1Fo ATP Synthase dimers located at the edge of cristae [17].

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. The mitochondria membrane and electron transport system. (A) Mitochondria are surrounded by an outer and an inner membrane, with different proteins involved in mitochondrial function. In the illustration of the most current concepts, cristae are separated from the intermembrane space by tight tubular junctions regulated by OPA1 and MICOS which directly interact with G

Additionally, a concept of utmost importance is the proton-motive force, the combination of the mitochondrial membrane potential (

Likewise, the transport system also produces ROS, the physiological byproducts of normal oxygen metabolism. Categorically, ROS include free radicals, mainly superoxide (O2•-), hydroxyl radical (OH•-), and singlet oxygen (1O2), as well as non-radical species such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). Under physiological conditions, several endogenous antioxidants prevent oxidative damage, such as the superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione peroxidase (GPx), and catalase (CAT) enzymes. Strikingly, excess oxidative damage impairs the integrity and permeability of cell membranes, simultaneously causing dysfunctions in the electron transport system, a hallmark of many diseases [25]. Classically, ROS overproduction causes

Noteworthy, the complex interaction of substrate concentration, oxidized and reduced forms of Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+/NADH) ratio, ATP/ADP ratio, and, more recently, calcium concentrations regulate mitochondrial oxidative metabolism. Conversely, mitochondrial calcium concentrations are low, ranging from 0,1 to 10 µM, and rapidly respond to increases in cytosolic calcium [27]. Then, the mitochondrial calcium uniporter (MCU) effectively senses extra mitochondrial calcium levels and mediates Ca2+ entry into the mitochondrial matrix, partially dissipating the mitochondrial membrane potential (

Additionally, Ca2+ regulates respiration independently of ATP demand [30]. To maintain calcium homeostasis, the mitochondrial sodium/calcium/lithium exchanger (NCLX) balances influx by extruding one Ca2+ in exchange with three sodium ions [31]. Notably, mitochondrial Ca2+ effects on different processes may differ, ranging from activation to shutdown. For example, moderate increases are necessary and sufficient to adjust ATP production to cellular demand, and Ca2+ overload leads to disruption of mitochondrial membrane integrity and irreversible oxidative damage decreasing ATP production capacity [32]. This phenomenon essentially results from three mechanisms: (I) increased mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake, after efflux from the endoplasmic reticulum and influx of Ca2+ from the extracellular space; (II) reduction of Ca2+ extrusion through NCLX; and (III) changes in mitochondrial Ca2+ buffering (Fig. 2). Therefore, impairment of mitochondrial calcium homeostasis is a recognized feature of the early stages of neurodegeneration, with direct implications in CNS diseases, with synergistic effects occurring between disruption of mitochondrial membrane potential, calcium overload, and ROS in mediating cell damage [27, 33].

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Calcium influx/efflux in mitochondria and calcium-regulated mitochondrial processes. Notably, mitochondrial Ca2+ effects on different processes may differ, ranging from activation to shutdown. The influx of calcium from the intermembrane space (IM) to the matrix occurs through the MCU and directly regulates enzymes involved with the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA; Pyruvate Dehydrogenase, Isocitrate Dehydrogenase, and Alpha-ketoglutarate Dehydrogenase) and also the malate-aspartate (MA) shuttle and Glycerol-3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase (G3PDH), increasing substrates for the transport system. Calcium also directly regulates complexes of the electron transport system (Complex III–V) and adenine nucleotide translocase. Calcium efflux occurs by the NCLX (mitochondrial sodium/calcium/lithium exchanger) balancing calcium concentrations in the mitochondria. This figure was crated by Microsoft Powerpoint 16.0 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). ANT, Adenine Nucleotide Translocase; MCU, mitochondrial calcium uniporter; NCLX, mitochondrial sodium/calcium/lithium exchanger; Glu, Glutamate; Asp, Aspartate.

Owing to the importance and complex relationship between

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. The dynamic life cycle of mitochondria and the processes of fusion and fission. Mitochondria cyclically switch between a solitary, post-fusion (network) state and a post-fission (solitary) state. Loss of potential results in fusion, which is rapid and triggers fission. After a fission event, the generated mitochondria can keep their membrane potential intact (black path), recover after depolarization (Recovery – green pat) or with depolarization (yellow path) being directed to degradation pathways. This figure was crated by Microsoft Powerpoint 16.0 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). MFN, mitofusin; FIS1, fission protein 1; DRP1, Dynamin-related protein 1.

Subsequently, the dynamics of these processes allow mitochondria to retain a more stable membrane potential after fission, although it can vary by up to 5 mV from the solitary period. Therefore, fission results in functionally different mitochondria. For fission to occur, the protein Dynamin-related protein 1 (DRP1) interacts with two proteins anchored in the outer mitochondrial membrane: the Mitochondrial Fusion Factor (Mff) and Mitochondrial fission 1 protein (FIS1), to a lesser extent [35]. In contrast, fusion combines the contents of the original mitochondria and requires an intact mitochondrial membrane potential, regenerating damaged mitochondria. Further, the fusion allows for rapid diffusion of mitochondrial matrix proteins combined with slower migration of inner and outer membrane components. In mammals, different GTPases of the dynamin family regulate mitochondrial fusion: in the inner mitochondrial membrane, OPA1 and mitofusins in the outer mitochondrial membrane (Mnf1 and Mnf2). A greater detail of these mechanisms is beyond the scope of this review; however, the reader may benefit from resorting to other sources [34, 36].

Importantly, the mitochondrial signaling that results in apoptosis (programmed cell death) results from the interaction of Ca2+ concentration with proteins of the Bcl-2 family. Anti-apoptotic proteins B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) and B-cell lymphoma-extra large (Bcl-XL) reduce endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ concentrations and upregulate mitochondria to maintain cellular homeostasis. This is possible thanks to its location on the membrane of both organelles. Conversely, the Bcl-2-associated X protein (BAX) and Bcl-2 homologous antagonist/killer protein (BAK), belonging to the same family, have a pro-apoptotic effect [27, 33]. Likewise, the regulation of this pathway is directly proportional to the concentrations of calcium released by the endoplasmic reticulum and consequent mitochondrial uptake, since an exacerbated increase results in the opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP), consequently changing the morphology, and inducing the release of cytochrome c, and activation of caspases, determining pro-apoptotic stimuli [27, 33]. However, the cellular and molecular mechanisms involved in these progressive changes (Fig. 4) can simultaneously interact to exacerbate injury and initiate neuronal repair [34, 36]. The pathophysiological mechanisms associated with TBI involve primary injury resulting from mechanical or inertial damage to white and gray matter, leading to cellular membrane disruption, content release, and diffuse axonal injury [37, 38]. Secondary injury refers to the progression of changes associated with primary brain injury, resulting in various neurological alterations that can have devastating lifelong consequences, such as persistent activation of a series of neurotoxic event cascades triggers the progression of structural damage, loss of neuronal function and connectivity, culminating in the death of neural cells adjacent to the injury focus [37]. Therefore, the extent and severity of secondary damage are proportional to the location and intensity of the primary insult. Mechanisms underlying secondary damage include excessive increases in extracellular glutamate (excitotoxicity), impairments in calcium (Ca2+) homeostasis, persistent inflammatory response, neuroenergetic deficiency, redox imbalance, vascular system dysfunction, ischemia, axonal protein accumulation, and mitochondrial dysfunction [39, 40].

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)-associated damage cascade. Biomechanical forces from trauma cause tissue deformation (primary damage), followed by dysregulation of blood flow and excessive release of excitatory neurotransmitters. Additionally, increased intracellular Ca2+ concentrations activate proteases (calpains) that degrade the neuronal cytoskeleton. Concurrently, Ca2+ overload in mitochondria disrupts metabolism, increases the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and activates apoptotic and necrotic cell death signaling pathways. This figure was crated by Microsoft Powerpoint 16.0 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA).

Experimental studies have revealed that the phospholipid cardiolipin translocates from the inner to the outer mitochondrial membrane following TBI, thereby tagging damaged mitochondria for selective removal via mitophagy [39]. These mitochondrial distress signals elicit local and systemic responses by interacting with specific receptors on immune cells. Likewise, activation of the mPTP is crucial for cell survival post-TBI [41]. In this context, mitochondrial Ca2+ is regulated by two transporters: the mitochondrial calcium uniporter (MCU), facilitating Ca2+ influx regulated by changes in the membrane potential, and the mitochondrial Na+/Ca2+/Li+ exchanger (NCLX), mediating Ca2+ efflux which is potentially inhibited following TBI [42]. Excessive Ca2+ within mitochondria can trigger the opening of the mPTP, resulting in mitochondrial edema and reduced oxidative metabolism, releasing mitochondrial Ca2+ and activating detrimental calcium-dependent proteases such as calpain [43]. Additionally, the loss of cytochrome c through the mPTP activates cellular apoptosis via caspases [41].

Noteworthy, in most experimental models of CNS diseases, mitochondrial dysfunction is a common source of cellular metabolic crisis [8, 9], especially following TBI [44, 45]. This partially reflects the pathological increase in intracellular calcium concentrations and mitochondrial calcium buffering, consequently decreasing mitochondrial ATP production, impairing other cellular functions, and concomitantly increasing ROS generations [46, 47]. Thus, with increased calcium exceeding the capacity for mitochondrial sequestration, selective destruction of the cytoskeleton can lead to cell death by apoptotic neurodegeneration [48]. Excess calcium induces the fragmentation of structural proteins of the neuronal cytoskeleton, such as alpha-spectrin, in addition to stimulating the hyperphosphorylation of Tau, classic molecular biomarkers of neurodegeneration, via calpain (mainly calpain-2) and caspases activities [49].

In this context, therapeutic interventions targeting mitochondria may delay or prevent secondary cascades that lead to cell death and neurobehavioral disability. Thus, the emerging interest in mitochondrial function in TBI reinforces the historically established importance of this organelle in the scientific literature. Although substantial conceptual evidence currently considers brain mitochondria as a potential therapeutic target against neurodegeneration, no pharmacological intervention with proven efficacy is available to date [11, 12, 13].

Nevertheless, research on rodents demonstrated promising outcomes in enhancing mitochondrial function following TBI. Currently, several drugs targeting mitochondrial metabolism are possible candidates for further repurposing for TBI patients, albeit most of the proposed interventions fail to provide benefits in clinical trials [11, 13]. In this section, we focus on mitochondrial-targetting drugs that showed promising results in pre-clinical studies that also were tested in human clinical trials, regardless of TBI severity. For instance, N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) has demonstrated significant neuroprotective effects in various animal models, particularly by mitigating secondary neuronal injury resulting from TBI, via the upregulation of glutathione levels (GSH), which functions as a free radical scavenger and an antioxidant, improving outcomes in TBI [50, 51]. Recently, a double-blind, placebo-controlled human trial evaluated the efficacy of NAC in patients with blast-induced mild traumatic brain injury. The treatment group received 2 g of NAC twice daily for the first four days, followed by 1.5 g of NAC twice daily for three days, and showed significant improvement (p

Similarly, Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) agonists, including rosiglitazone and pioglitazone, also presented neuroprotective properties in a preclinical study, potentially reducing axonal injury modulating apoptosis, autophagy, and microglial activation [53]. Interestingly, the pioglitazone therapeutic window is delayed, with better results obtained following treatment initiated 18 hours following injury [54]. The effects also depend on dosage and mitoNEET presence, which modulates calcium-related mitochondrial mechanisms [55]. In addition, two studies showed significant effects on mitochondrial dysfunction after severe and mild preclinical TBI, which extended to sustained cognitive performance and reduced cortical damage, with modest antioxidant and tissue-sparing effects [19, 54]. Deng et al. [56] combined an animal model of TBI with brain tissue, blood, and cerebrospinal fluid from forty-five patients with moderate to severe TBI [57]. Strikingly, the study reported brain edema and high expression of the inflammatory factors Interleukin-6 (IL-6), nitric oxide (NO), and the apoptotic factor caspase-3 in TBI patients. Treatment with pioglitazone in TBI rats showed beneficial effects, and PPAR type gamma (PPAR

Importantly, mild mitochondrial uncoupling with exogenous stimuli to supplement the endogenous response to TBI has shown beneficial effects, implementing low doses of drugs that promote mitochondrial uncoupling, such as 2,4-dinitrophenol (DNP), carbonyl cyanide-4-phenylhydrazone (FCCP), and mitochondrial uncoupler prodrug of 2,4-dinitrophenol (MP201), which demonstrated positive effects in pre-clinical studies, albeit still under scrutiny regarding human clinical trials [59, 60]. Moreover, a few small-scale clinical trials evaluated cyclosporin A, which delays mPTP opening and regulates calcium buffering, showing no beneficial effects [57, 61].

Further, guanosine, an endogenous nucleoside, also showed neuroprotective effects following mild TBI, increasing oxidative phosphorylation and ETS function, resulting in preserved motor performance and cognitive functions [62], an effect mediated by the A2a Adenosine receptor [63]. Likewise, testosterone can be considered, since it potentially modulates several neurodegenerative processes in mice subjected to severe TBI. A particular study [42] showed that TBI increased calcium uptake and impaired calcium extrusion via the NCLX, effects that were linked to a deterioration in mitochondrial membrane potential dynamics and a decreased efficiency in mitochondrial ATP synthesis coupling, and these effects were mitigated by testosterone. Also, there was an observed increase in hydrogen peroxide production post-TBI, without a corresponding change in the immunocontent of the mitochondrial Superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) protein, and testosterone prevented the increase in tau fragmentation and its phosphorylation at serine 396, and increased in alpha-spectrin cleavage via calpain-2 activation. Additionally, testosterone decreased both caspase-3 activation and the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio, indicating downregulation of mitochondrial apoptotic signaling pathways. Hence, testosterone administration after severe TBI enhanced calcium extrusion through the NCLX exchanger and improved mitochondrial function, reducing the overexpression of molecular factors associated with neurodegeneration. Thus, since TBI often induces hypopituitarism and testosterone reduction, testosterone may help improve metabolic, neurological and functional outcomes, albeit additional investigations are necessary [64]. Notably, a small clinical trial reported functional improvements in men receiving testosterone following severe TBI when compared to rehabilitation alone [65]. Another promising approach is mitochondrial transplantation, in which mitochondria from healthy cells are transferred to stressed cells in damaged tissue, to achieve neuroprotective effects and mitigate cognitive dysfunctions [66, 67].

Remarkably, the failure of translation from bench to bedside in the field of TBI is due to many challenges, including failure the lack of translation of effects from preclinical models to humans, and the fact that current clinical trials can be full of shortcomings and design flaws [68, 69]. Much of the literature has focused on severe TBI, drawing criticism due to the challenges coming from the large variability in TBI pathology (contusions, diffuse axonal injury, subdural hematomas), patient demographics (age, sex), and secondary complications [70]. Furthermore, many often highlight other problems: provision of emergency care and critical care is uneven across regions; surgical management varies; inconsistent rehabilitation protocols during hospitalization and post-discharge; no assessment of pharmacokinetics/biology for new therapies; and poor sensitivity of outcomes (e.g., Glasgow Coma Scale) [70, 71]. These limitations may hinder the potential of mitochondrial regulation in TBI, although numerous initiatives are being taken to overcome them [71, 72].

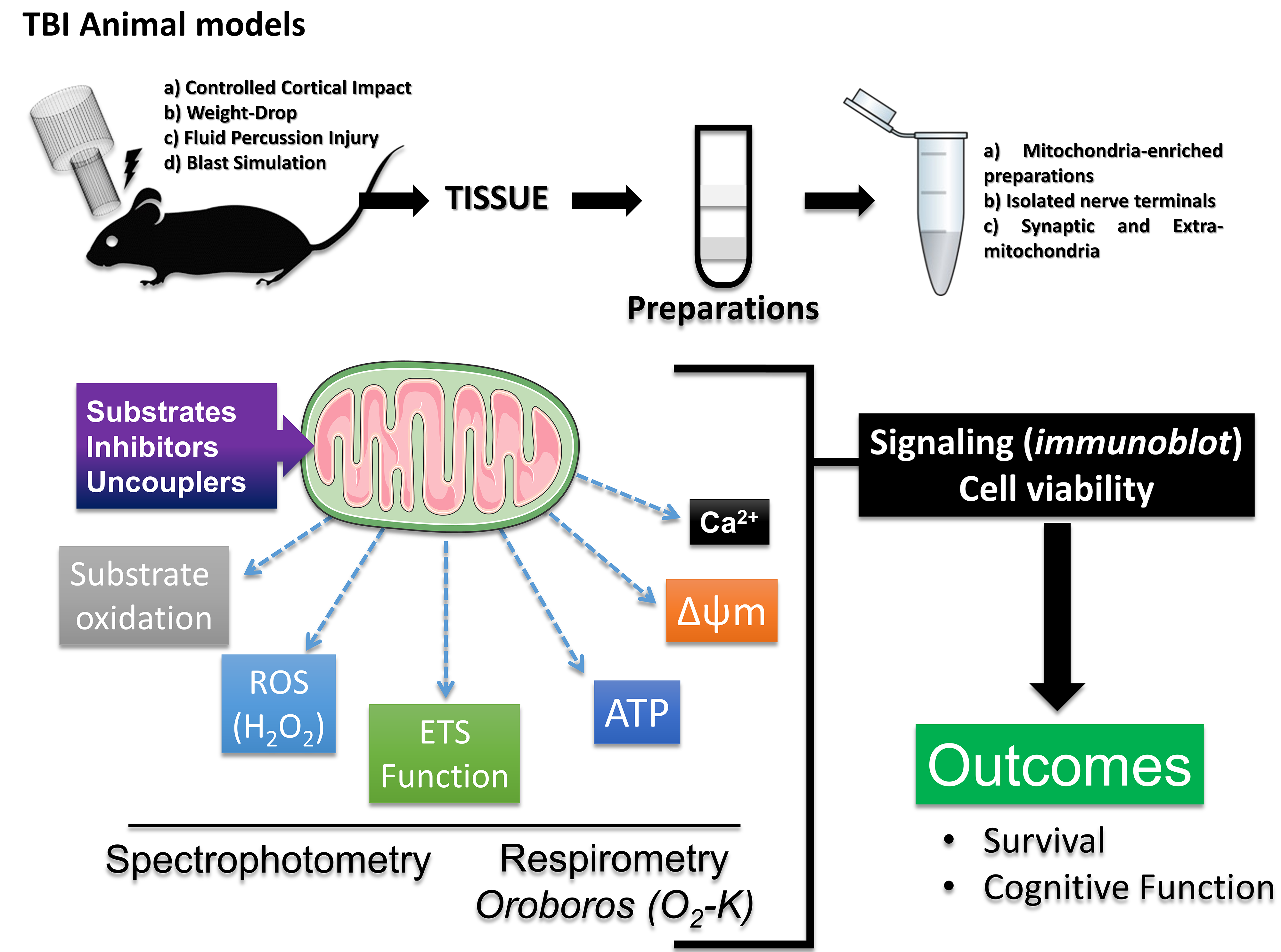

Given the complexity of mitochondrial functions, current literature indicates that researchers can combine tools to optimize studies exploring mitochondrial mechanisms in different physiological contexts, including TBI. Hence, considering the appropriate sample and striving to combine different analyses encompassing the main functions of mitochondria is of utmost importance. This review reinforces a mitochondrial diagnostic model in preclinical rodent studies based on various guidelines for mitochondrial function analysis [73, 74]. Firstly, Percoll density gradient centrifugation [75, 76] can provide mitochondria-enriched samples from isolated nerve terminals and extra-synaptic mitochondria from the whole brain or single hemisphere [77], or tissue homogenates from specific brain regions [42, 78], albeit density gradient centrifugation may limit small brain region assessments due to low mitochondrial yield. Recently, the fractionated mitochondrial magnetic separation (FMMS), employing magnetic anti-Tom22 antibodies can provide better yield in obtaining isolated functional synaptic and non-synaptic mitochondria populations from mouse cortex and hippocampus [79]. Subsequently, following the combination with a respiration buffer [42, 78], oxygen consumption, and ATP synthesis capacity are evaluated through high-resolution respirometry. Further, spectrophotometric assays for other important aspects (i.e., hydrogen peroxide synthesis, membrane potential dynamics, and calcium handling capacity) complement this analysis. Additionally, techniques to assess glucose uptake and cellular signaling, such as immunoblotting or immunohistochemistry, can add mechanistic insights to explain the outcomes (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. Mitochondrial diagnostics. This review also reinforces a model for mitochondrial diagnosis in preclinical studies on rodents, assessing oxygen consumption and ATP synthesis capacity through high-resolution respirometry. This analysis is complemented by spectrophotometric assays to evaluate hydrogen peroxide synthesis and other reactive species, membrane potential dynamics, and calcium handling capacity. Additionally, techniques for assessing cellular signaling, such as immunoblotting or immunohistochemistry, can add mechanistic components to explain the outcomes. This figure was crated by Microsoft Powerpoint 16.0 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). ETS, electron transport system; H2O2, hydrogen peroxide.

The present review discussed the main mitochondrial mechanisms in physiological and pathological conditions, focusing on TBI. Strikingly, an imbalance of mitochondrial homeostasis is present in most neurodegenerative diseases. Since mitochondria are the main energy source of neurons, the mentioned mechanisms are involved in the dysfunction of mitochondria, leading to neurodegeneration and cell death. The modulation of mitochondrial bioenergetics is an important pathophysiological mechanism, and the literature that provides functional and molecular evidence of the importance of mitochondria as a therapeutic and prophylactic target in different diseases is extensive. Therefore, targeting mitochondria and scrutinizing the related mechanisms parallels the advancements in various CNS diseases, especially in TBI. The exposed mechanisms can be explored to enhance experimental models, investigating alternative therapeutic strategies to prevent worse outcomes. Thus, mitochondria in TBI serve as a nexus for neuronal fate: survive or perish.

RBC was responsible for the conception, design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, and writing of the manuscript. RBC contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. RBC read and approved the final manuscript. RBC has participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

I am grateful for the years spent in the Biochemistry Department at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, which directly contributed to this study.

This research received no external funding.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.