1 Health Neuroscience Collaboratory, College of Health Solutions, Arizona State University, Phoenix, AZ 85004, USA

2 Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Diego, CA 92093, USA

3 Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843, USA

Performance neuroscience is a multidisciplinary field that investigates the brain mechanisms underlying human performance in various cognitive, physical, and mental domains, such as cognitive functions, motor skills, sports, arts and creativity, and emotion regulation and resilience. It seeks to understand how the brain supports and optimizes performance in different contexts or conditions and how factors such as genetics, environment, mindset, training, and individual differences influence performance outcomes in order to optimize those outcomes. The body (physiology) and the brain closely interact to support peak or optimal performance [1]. Therefore, identifying brain and body biomarkers of optimal performance is also a growing research area in performance neuroscience.

1. Cognitive Performance investigates the brain mechanisms of performance in various cognitive domains, such as attention, memory, creativity, perception, learning, problem-solving, and decision-making. Understanding these processes can help optimize cognitive performance in academic, professional, and everyday settings.

2. Motor and Sports Performance examines the neural mechanisms supporting motor control, coordination, and movement optimization. Motor performance is critical for sports performance, which often involves examining the brain mechanisms subserving athletic skills, motor learning and planning, expertise development, and performance-enhancement strategies. It also investigates how athletes optimize their mental and physical abilities to achieve peak performance in competition.

3. Emotion Regulation and Resilience focuses on the neural mechanisms of emotion regulation and resilience in response to various situations. In particular, it focuses on how to adapt positively and effectively, while maintaining and optimizing health and performance, in the face of setbacks and challenges [1].

4. Performance in Extreme Environments — heat, cold, and altitude often present unique challenges to the body and brain and necessitate specific adaptations in order to optimize human performance. This research often focuses on how to monitor and maintain optimal physical and mental states for peak performance and prevent adverse effects in extreme environments.

5. Training and Skill Acquisition explores the mechanisms of neuroplasticity that promote learning and adaptation in different situations. For example, it examines how training and practice after injury shape brain function and structure, leading to skill acquisition, expertise development, performance improvement, and rehabilitation [2].

6. Individual Differences seeks to understand how brain structure and function, and genetic and environmental factors contribute to individual differences in human performance and resilience. Moreover, it examines how training can be tailored to individuals to promote performance (personalized training for optimal performance) [3].

7. Health and Performance Relationship — health neuroscience and performance neuroscience are two different fields that are often studied separately [4]. However, health and performance are closely related as they both influence and depend on each other. For instance, good physical health is essential for optimal physical performance and directly impacts task performance. Maintaining good mental health is critical for effective stress management, emotion regulation, and cognitive functioning, which also contribute to optimal performance. Therefore, it is imperative to develop and apply a holistic approach to support and promote both health and performance. This approach recognizes the importance of physical, mental, and social aspects of health in achieving optimal performance in different aspects of life. Balancing these various aspects of health and addressing any imbalances can lead to improvement in overall human functioning and performance. Similarly, investing in performance improvement and optimization strategies can also contribute to better health outcomes and overall well-being.

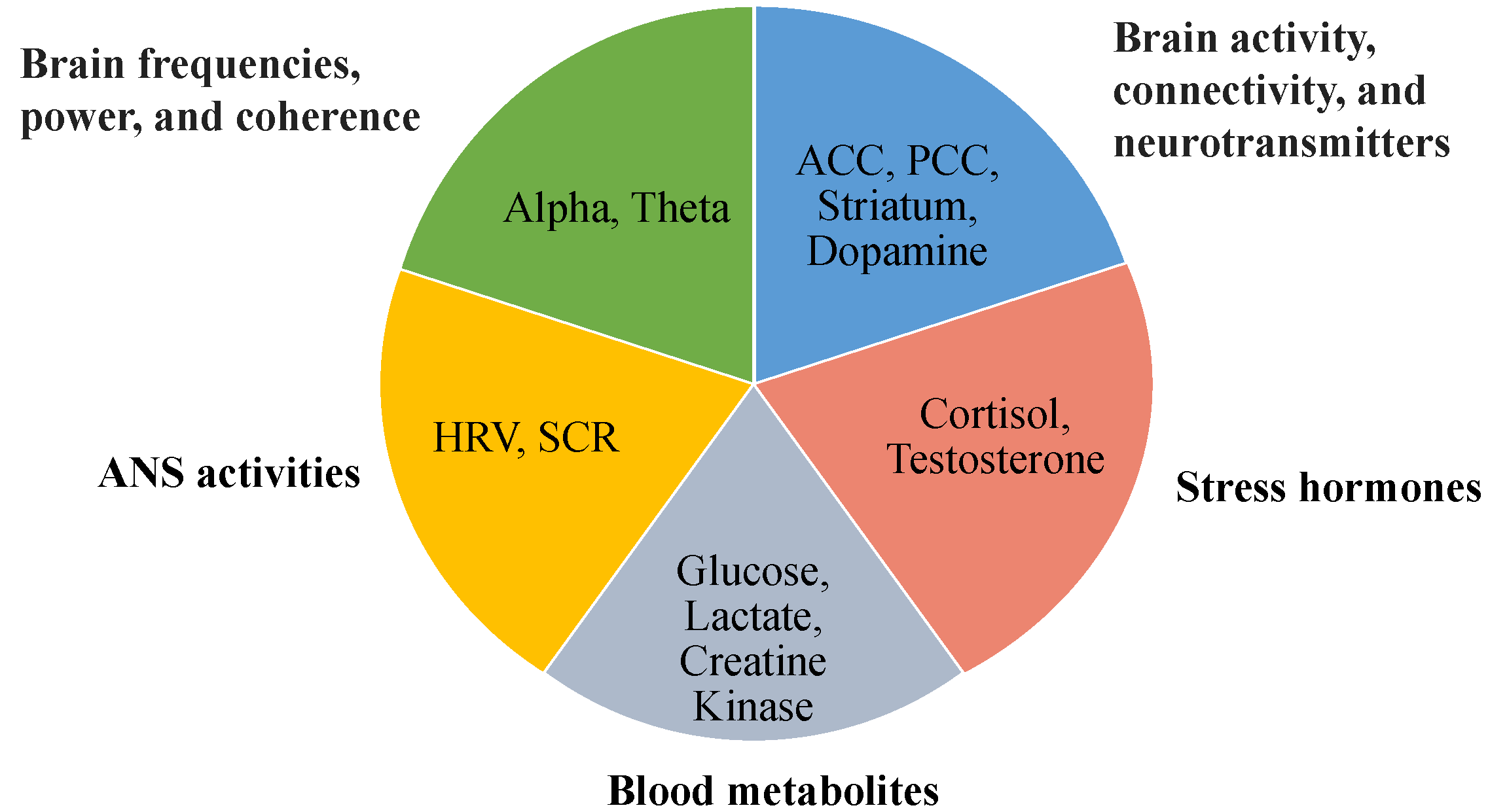

Peak performance refers to a state of exceptional functioning in which individuals or groups achieve their highest levels of performance, productivity, and effectiveness. It is similar to the sense of flow, focus, engagement, and excellence, that occur when individuals are fully engaged and performing at their best [5]. Therefore, peak performance likely involves the coordination and optimization of both the central and autonomic systems (brain and body) [6]. For example, the mental processes of peak performance involve at least attention, engagement, motivation, monitoring, and self-control (or executive function). We speculate that key brain areas such as the anterior and posterior cingulate cortex (ACC, PCC), and striatum (APS circuit) actively participate and support peak performance and related processes [6, 7, 8, 9]. Depending on the tasks, other brain areas and networks also engage, such as the sensory-motor areas involved in optimal motor control, coordination, and balance [2, 5]. Likewise, brain biomarkers such as

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Biomarkers of Peak Performance. ACC, anterior cingulate cortex, PCC, posterior cingulate cortex; ANS, autonomic nervous system; HRV, heart rate variability; SCR, skin conductance response.

Overall, performance neuroscience provides valuable insights into the brain-behavior-physiology relationships underlying human performance and has important implications for education, sports, rehabilitation, business, arts, and other fields that are aimed at optimizing performance and promoting health and well-being. However, there are still many unsolved questions, like how do pre-existing factors such as genetics and experiences affect performance, how do the brain and body work together to optimize performance, and how can we cultivate peak performance effectively?

YYT and RT — Writing, Conceptualization, Original draft. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. Both authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This work is supported by the Office of Naval Research (grant N000142412270).

The authors declare no conflict of interest. Yi-Yuan Tang is serving as one of the Editorial Board members of this journal. We declare that Yi-Yuan Tang had no involvement in the peer review of this article and has no access to information regarding its peer review. Full responsibility for the editorial process for this article was delegated to Gernot Riedel.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.