1 Department of Neurosurgery, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, OK 73104, USA

2 Graduate College, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, OK 73104, USA

Abstract

Resting state networks (RSNs) of the brain are characterized as correlated spontaneous time-varying fluctuations in the absence of goal-directed tasks. These networks can be local or large-scale spanning the brain. The study of the spatiotemporal properties of such networks has helped understand the brain’s fundamental functional organization under healthy and diseased states. As we age, these spatiotemporal properties change. Moreover, RSNs exhibit neural plasticity to compensate for the loss of cognitive functions. This narrative review aims to summarize current knowledge from functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies on age-related alterations in RSNs. Underlying mechanisms influencing such changes are discussed. Methodological challenges and future directions are also addressed. By providing an overview of the current state of knowledge in this field, this review aims to guide future research endeavors aimed at promoting healthy brain aging and developing effective interventions for age-related cognitive impairment and neurodegenerative diseases.

Keywords

- aging

- resting state networks

- functional connectivity

- neuroplasticity

- cortical reserve

- fMRI

The human brain is a complex organ composed of billions of neurons interconnected through intricate neural circuits [1]. It is organized both structurally and functionally into specialized regions and networks that collectively enable a wide range of cognitive and behavioral functions. A classic example of the brain’s organization is that of the classification of the cortex into distinct areas by Brodmann based on the brain’s cytoarchitecture [2]. These regions commonly known as Brodmann Areas, are associated with different functions including cognition, sensation, and motor control [3]. While this cytoarchitectural mapping has provided a foundational understanding of the cerebral cortex’s functional organization over the past 100 years, contemporary neuroscience research has revealed more detailed and interconnected functional networks that extend beyond Brodmann’s original delineations [4]. Task-based studies have been instrumental in elucidating the functional organization of the brain by examining how specific cognitive tasks or stimuli activate distinct brain regions and networks [5]. While traditionally, brain activity has been studied in the context of task-specific activations, it has become increasingly evident that the brain also exhibits organized patterns of activity even in the absence of explicit tasks or external stimuli. These intrinsic patterns of brain activity, known as resting state networks (RSNs), represent the brain’s spontaneous fluctuations and are believed to underlie its fundamental functional organization [6].

In a seminal paper by Biswal and colleagues [7], an RSN was reported that was mapped by functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) signal in the bilateral regions of the sensorimotor (SM) cortex in the low-frequency band (

As the global population is aging, age-related cognitive impairments are ever-increasing and have a negative impact on quality of life. Even in the absence of disease, cognitive capacities that are necessary for abstract thought, reasoning, and decision-making deteriorate with age in older individuals [33]. While some degree of cognitive decline is considered a normal part of aging, it can vary significantly among individuals and may be exacerbated by underlying neurodegenerative processes. Such cognitive decline is associated with alterations in the brain’s structure and function [34, 35, 36, 37].

A growing number of studies have revealed that aging is associated with alterations in the functional connectivity (FC) and integrity of various RSNs (See Sala-Llonch et al. [38], 2015 for a review). These changes often manifest as for example decreased network connectivity, reduced network segregation, and disrupted network dynamics [39]. Importantly, such alterations in RSNs have been correlated with poor sleep [12] and cognitive decline, suggesting that they may serve as biomarkers for monitoring cognitive aging and identifying individuals at risk for more severe cognitive impairment [40] and neurodegenerative diseases [41, 42, 43, 44].

The present review focuses on alterations in RSNs in healthy aging. Structural changes of the brain are not included, and fMRI studies are primarily covered to limit the scope of the review. In section 2, commonly used techniques to estimate RSNs are briefly described. Section 3 summarizes study findings on alteration in RSNs with aging in healthy individuals. In section 4, underlying mechanisms and factors influencing RSN alteration are discussed. In section 5, the relevance of RSNs in neurodegenerative diseases is briefly discussed. The electrophysiological underpinnings of RSNs are discussed in section 6. In section 7, challenges and future directions are discussed.

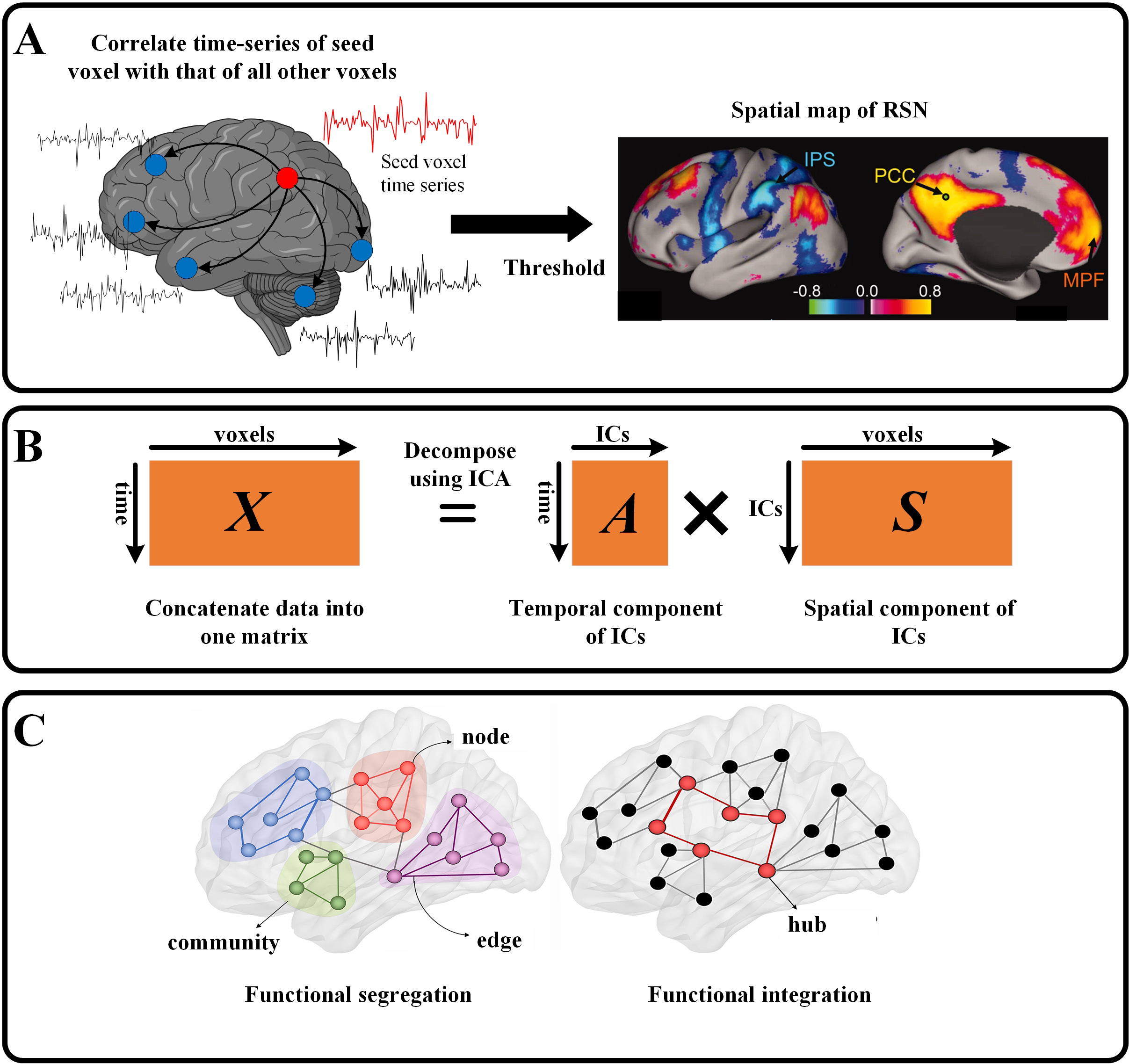

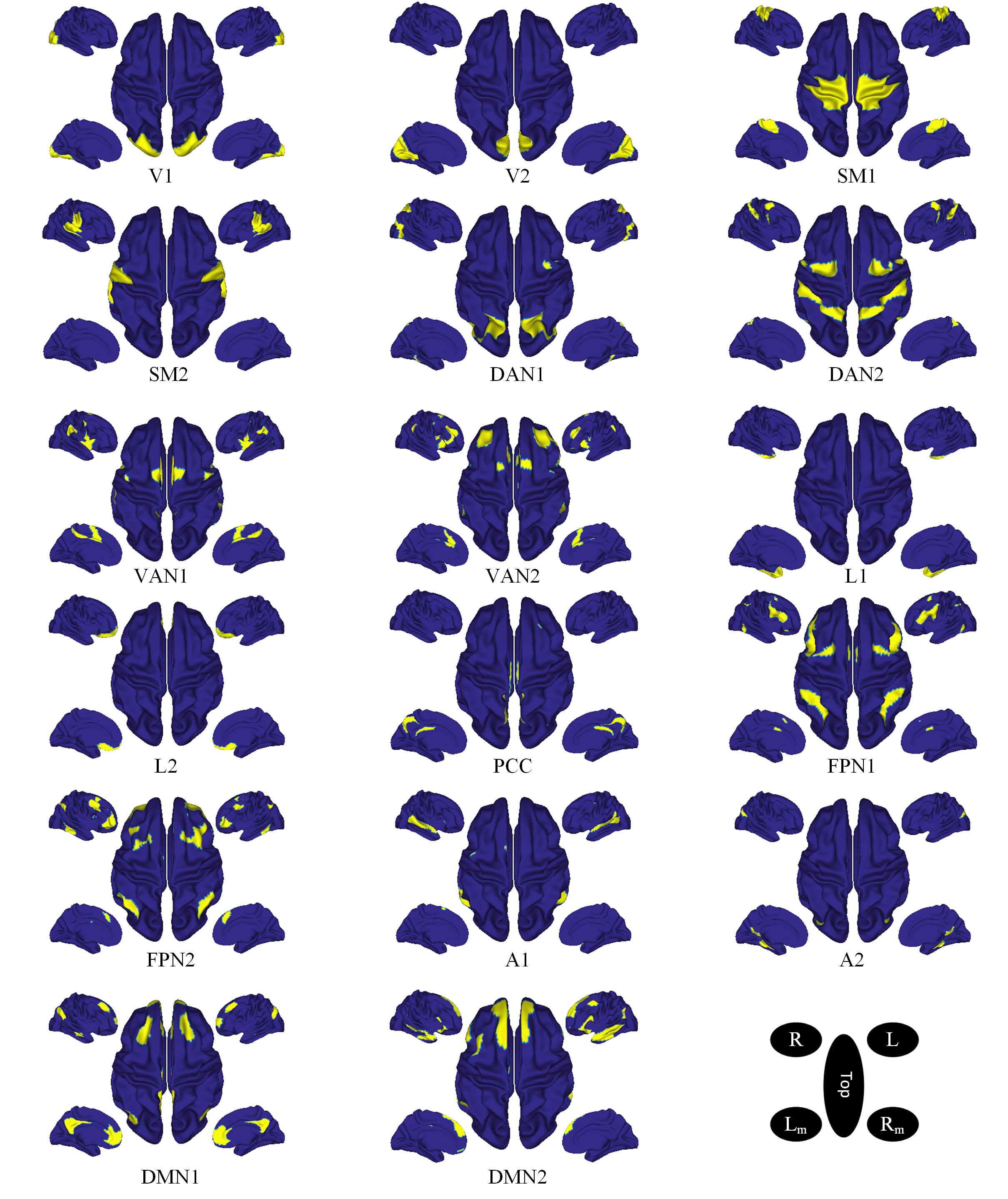

A popular and relatively straightforward method of calculating RSNs is the so-called seed-based connectivity analysis (SCA) which attempts to find correlated brain activity [7]. In this method, a “seed” is first determined, which can be a voxel time series or an average of the timeseries of a region-of-interest (ROI) (Fig. 1, Ref. [45, 46]). Then the correlation between the seed’s timeseries and the timeseries of all other voxels or ROI is calculated. These correlation values are thresholded to obtain spatial maps representing a network [47]. Thus, the total number of networks becomes equal to the number of seed choices. Fig. 2 (Ref. [48, 49]) shows the spatial maps of major RSNs and their sub-networks estimated from seed-based connectivity from about 1000 participants [48]. While SCA is easy to implement and interpret, it has an inherent limitation i.e., it is highly dependent on the choice of the seed location, thereby biasing the RSN to this choice [50].

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Schematic of resting state functional connectivity techniques. (A) In seed-based correlation analysis, the time series of a seed (or region-of-interest (ROI)) is correlated with that of all voxels. These correlation values are then thresholded to obtain spatial maps representing a network (adapted with permission from Ref. [45] Copyright (2005) National Academy of Sciences, USA). (B) In an independent component analysis (ICA), the data are re-arranged in a single matrix (X) which is then decomposed into a mixing matrix (A) containing IC timeseries and source matrix (S) containing IC spatial maps. (C) In graph theory, every voxel (or ROI) is a node and the functional connectivity between the nodes is an edge. A collection of connected nodes forms a community. Communities are connected by highly connected nodes called hubs [46] (Adapted with permission from Ref. [46]). IC, Independent Component; IPS, Inferior Parietal Sulcus; PCC, Posterior Cingulate Cortex; MPF, Medial Prefrontal; RSN, Resting state network.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Spatial maps of resting state networks and their sub-networks. These networks were estimated from seed-based connectivity from 1000 participants and projected onto the cortical surface as the interface between white matter and gray matter [48]. V, visual; SM, somatomotor; DAN, dorsal attention network; VAN, ventral attention network; L, limbic; PCC, posterior cingulate cortex; FPN, frontoparietal network; A, auditory; DMN, default mode network; A, anterior; L/R, left/right; Lm/Rm, left/right medial wall. Subnetworks are denoted by numeric values (Figure adapted from [49]).

The data-driven independent component analysis (ICA) approach, on the other hand, is not dependent on the selection of seed locations and can simultaneously reconstruct multiple networks [20, 51]. ICA decomposes complex neuroimaging data into spatially and temporally independent components [52]. Unlike SCA which relies on predefined regions of interest or seed-based analyses, ICA allows for data-driven exploration of functional connectivity patterns across the entire brain. Although methodologically different, ICA analysis has been shown to yield RSNs similar to SCA-derived networks, although these two are not identical [47, 53]. In ICA, the number of components must be indicated. Previous work has indicated 8 to 10 functionally relevant networks [54] by estimating a total of 20 or 30 components, while other works suggest 20 functionally relevant networks or greater [55]. Nevertheless, choosing an optimal number of components is an area of research. While ICA is data-driven and can identify networks without prior assumptions, it may miss subtle but important interactions within or between networks, reported by other techniques such as coactivation pattern analysis [56].

Another popular technique to study the brain’s FC is to use graph theory in which the brain is described as an interconnected network consisting of nodes (representing neurons or regions) and edges (representing connections or pathways) [57]. The complexity of this network can be varied according to the research question at hand [58]. Such an approach provides a theoretical framework for investigating the biological underpinnings of brain function by allowing bridging together structural and functional connectivity [59].

Several studies have investigated the effect of age on RSNs. Findings from selected studies are summarized in Table 1 (Ref. [60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75]). A common finding of these studies is reduced connectivity between nodes of the networks especially the DMN, salience, and executive attention networks [38]. For example, using an ICA-based approach, Damoiseaux et al., 2008 [60], reported decreased activity in older participants compared to younger ones in DMN despite adjusting for network-specific gray matter volume. Andrews-Hanna et al., 2007 [61] studied the aging effects on the subdivisions within the DMN and showed that the anterior to posterior components within the DMN were most severely disrupted with age in individuals who were not Alzheimer’s patients suggesting that cognitive decline in normal aging is associated with functional disruption in the coordination of large-scale brain systems that support cognition. In another study employing ICA and SCA approaches, Jones et al., 2011 [75] showed that FC in the anterior DMN increased whereas that in the posterior DMN decreased with age. Betzel et al., 2014 [62] employed whole-brain FC and graph theory to study the effect of age on several brain networks. They showed that the FCs within RSNs decreased with age affecting several networks including DMN, attention, visual, and somatomotor networks. On the other hand, the FCs increased with age between RSNs, particularly among parts of DAN, salience, and somatomotor networks. Moreover, using component modularity as a metric they showed that at the system level, components of the control, attentional, limbic, and visual networks became functionally less cohesive with age [62]. The decrease in modularity has also been reported in another study [63].

| Reference | Sample | Method | RSN changes |

| Damoiseaux et al., 2008 [60] | 10 YA; 20 OA | ICA | Decreased activity in OA in DMN. |

| Jones et al., 2011 [75] | N = 341 | ICA, SCA | Anterior DMN FC increased with age; Posterior DMN FC decreased with age. |

| Onoda et al., 2012 [64] | N = 73 | ICA, SCA | FC in SN decreased with age; Between-network connectivity between SN-Auditory, DMN-visual decreased with age. |

| Andrews-Hanna et al., 2007 [61] | N = 93 | SCA | Anterior to posterior components within the DMN were disrupted in aging; FC in the DAN increased with aging. |

| Wang et al., 2010 [65] | N = 17 | SCA | FC between the hippocampus and posteromedial regions predicted overall memory performance in OA. |

| Tomasi et al., 2012 [66] | N = 913 | FCD mapping | Long-range FCD decreased in DMN and DAN and increased in somatosensory and subcortical networks in aging. |

| Betzel et al., 2014 [62] | N = 126 | SCA, Graph theory | Within-network FCs decreased; FCs between RSNs increased. |

| Chan et al., 2014 [69] | N = 210 | Graph theory | Segregation decreased; Within-network FCs decreased; FCs between RSNs increased. |

| Song et al., 2014 [63] | 24 YA; 26 OA | Graph theory | FC in DMN and SM decreased; Modularity decreased. |

| Sala-Llonch et al. 2014 [67] | N = 98 | Graph theory | Short-range FC increased; Long-range FC decreased. |

| Grady et al., 2016 [68] | 45 YA; 39 OA | Graph theory | Within-network FCs decreased; FCs between RSNs increased; FPN modulated DMN FC. |

| Spreng et al., 2016 [72] | 54 YA; 61 OA | SCA | Within-network FCs decreased in DMN and DAN; FCs between RSNs increased in DMN and DAN; FC between DMN and DAN with MTL decreased. |

| Varangis et al., 2019 [70] | N = 427 | Graph theory | Reduced average intra-network FC; Reduced FC in DAN, mouth network, auditory network, and CON. |

| Participation coefficient increased; Segregation decreased; Local efficiency decreased. | |||

| Stumme et al. 2020 [71] | N = 772 | Graph theory | Within-network FCs decreased; FCs between RSNs increased; Increased segregation in DMN and VAN in females compared to males; Increased integration in SM in males. |

| Pedersen et al., 2021 [73] | N = 284 | Graph theory | Brain segregation of associative networks decreased with age accelerating at 58 years. |

| Sanders et al. 2023 [74] | N = 628 children and YA | Graph theory | Linear within-network FCs decreased in PO, SN, VAN, SM, and Auditory networks. |

| Non-linear trend showed increasing within-network FCs in childhood which became stable in adolescence. | |||

| Non-linear between-network FC age-related differences occurred between higher-order cognitive, attention, and SM networks. CON-DAN and FPN-VAN FC increased from childhood to middle adolescence and remained stable into late adolescence. |

CON, Cingulo-Opercular Network; DAN, Dorsal attention network; FCD, Functional connectivity density; ICA, Independent component analysis; OA, Older adults; PO, Parieto-occipital; SM, Sensorimotor network; SN, Salience network; VAN, Ventral attention network; YA, Younger adults; SCA, seed-based connectivity analysis; DMN, default-mode network; FC, functional connectivity; RSNs, resting state networks; FPN, frontoparietal network; MTL, Medial Temporal Lobe.

In another study, Onoda et al., 2012 [64] showed that FC in the salience network decreased with aging. Moreover, the between-network connectivity between the salience network and auditory network, and between DMN and visual network decreased with aging. Furthermore, the disruption to the salience network was associated with cognitive decline [64]. Using SCA, Wang et al., 2010 [65] showed that the FC between the hippocampus and posteromedial regions predicted overall memory performance in older adults. The posteromedial cortices include regions of the DMN specifically the precuneus and posterior cingulate [65].

In another line of research, in a whole-brain technique, Tomasi et al., 2012 [66] used FC density (FCD) mapping to study the interaction between multiple brain networks in 993 individuals. They showed that long-range FCD decreased in DMN and DAN but was increased in somatosensory and subcortical networks in aging. However, such effects were not as strong for short-range FCD. These results imply that aging may affect long-range connections more than short-range connections and that aging also impact the DAN in addition to the DMN. These findings may be the cause of the aging-related decline in attention processes [66]. Another study reported an increase in within-network FCs but a decrease in long-range FCs between RSNs [67]. These results support the hypothesis that certain key brain regions or hubs [76] could be involved with neuronal recruitment in closer regions, leading to an increase in local FC [77], or act as a regulator of other brain regions such as the frontoparietal network as a regulator of DMN [68]. The decrease in between-network connectivity reported by another study by Onoda et al., 2012 [64] showed that the between-network connectivity among the salience network and auditory network, and between DMN and visual network decreased with aging. Furthermore, the disruption to the salience network was associated with cognitive decline [64].

Some studies have combined the within-network and between-network FCs into a single metric known as functional segregation which is characterized by neuronal processing executed by brain regions inside “communities” that are functionally related to each other. These communities consist of dense connections among members of the same community. However, the connections are less dense between members of different communities. Such modeling allows the detection of communities, and the study of their composition and their interaction with each other [59], and are critical for understanding mental processing and cognition [78]. Network hubs allow efficient communication between communities and information integration [79]. At younger ages, brain networks tend to be more segregated with individual networks specializing in specific cognitive processes [14]. With aging, the segregation between brain networks decreases as a result of increased between-network FC and decreased within-network FC [68, 69, 70] supporting the idea of de-differentiation (decrease of functional specialization of brain networks) with aging [80] which has also been shown in a task-based study [81]. In one study, the investigator found systematic sex-related network differences. Specifically, the elderly female participants showed increased segregation among DMN and VAN compared to males. The males on the other hand had a more integrated sensorimotor network compared to the females [71].

The anti-correlation between large-scale networks is a key feature of functional organization in humans [45, 82] and is reported as positive within-network FC concomitant with negative between-network FC of the DMN and DAN [45]. Such a coordinated activity may help in allocating attentional resources and is important for healthy cognitive function [83]. Using SCA, Spreng et al., 2016 [72] showed that there was a pattern of reduced within-network FC in DMN and DAN but an increased between-network FC among these two networks. Moreover, using a task-based paradigm involving autobiographical planning, they showed reduced anticorrelation between DMN and DAN in aging individuals. In addition, the FC between both these networks and the medial temporal lobe (MTL) was reduced in aged individuals compared to the younger ones [72]. MTL has a critical role in episodic memory [84] which is highly affected in age-related dementia as revealed by reduced FC in mild cognitive impairment [85, 86], and Alzheimer’s [87].

The brain FCs alter throughout human life as the brain’s morphology changes [73, 88]. Advances in fMRI have enabled to observe such changes even in the fetal brains in utero [89]. Linear analyses have shown conflicting results as to how such changes occur over time. For example, while several studies have reported a linearly increasing trend of between-network FCs with age [90, 91], others have reported decreasing trends [92, 93]. Recently, studies have reported non-linear changes in FC with age. For example, Sanders et al., 2023 [74] found that within-network resting-state FCs increased non-linearly in childhood which became stable in adolescence. Moreover, between-network FCs age-related differences occurred non-linearly between higher-order cognitive, attention, and SM networks. Cingulo-Opercular Network (CON)-DAN and FPN-VAN FC increased from childhood to middle adolescence and remained stable into late adolescence. Another study showed that brain segregation of the associative networks decreased with age and started to accelerate at 58 years [73]. These studies highlight the importance of studying the brain’s changing FCs longitudinally particularly at times of early development and aging.

The exact reason for changes in resting-state FC changes in aging are not fully understood. It is thought that an increase in between-network FC could be a compensatory mechanism to maintain cognitive functions [94]. This is consistent with the observation that some aging adults are able to maintain cognitive abilities compared to others who show deteriorating cognition with aging. While the exact mechanisms to explain this difference among aging individuals are not clear [95], one hypothesis to explain this is the cognitive reserve which refers to the brain’s ability to maintain cognitive function despite age-related or even pathological changes. It encompasses factors such as neural plasticity and compensatory mechanisms, which can buffer against cognitive decline and delay the onset of symptoms in for example, neurodegenerative diseases [96]. RSNs have been used to study the brain’s cognitive reserve mechanisms in aging [97]. In a large study (n = 602, 18–88 years), Tsvetanov et al., 2016 [98] analyzed fMRI data and reported that cognitive ability was influenced by the strength of connection within and between functional brain networks (salience, DAN, and DMN) and was dependent on age. Compared to younger adults, older adults showed an increased rate of decay of intrinsic neuronal activity in multiple regions of the brain networks, which was associated with cognitive performance. Thus, there was an increased reliance on network flexibility to sustain cognitive function with age-related neuronal decay [98].

The decline in memory in aging individuals may also be explained in part by alterations in FC. Memory consolidation involves coordination between different large-scale RSNs [99]. The study of RSNs has helped elucidate the underlying mechanism of age-related memory decline. For example, in a study involving healthy young and older adults, Faßbender et al., 2022 [100] studied the age effects on memory consolidation. They reported reduced efficiency of FC within the salience network, and between DMN, and central executive networks during consolidation in aging. The study concluded that inefficient memory consolidation could partly be responsible for age-related memory decline and that memory consolidation requires a complex interaction between large-scale brain networks which also decreases with age [100]. In a resting-state study, Fang et al. [101] demonstrated the positive impact of sleep at daytime which resulted in an increase in FC within the striato-cortico-hippocampal network after motor learning in young adults. However, this FC decreased in older adults, demonstrating that aging individuals lose the benefit that sleep affords to memory consolidation [101]. These results strengthen the hypothesis that aging is associated with a decreased segregation of functional brain networks, which may impair learning and memory [102, 103]. Poor sleep can exacerbate cognitive decline in aging [104]. In a study involving healthy adults (n = 54, 20–68 years old), Federico et al., 2022 [105] reported that a reduction in sleep quality was associated with differences in FC in the limbic and fronto-temporo-parietal brain regions. Furthermore, sleep quality was associated with a reduction in working memory and an increase in depression and anxiety [105]. Therefore, understanding sleep pathophysiology and disruptions in brain networks in aging could allow one to better predict the risk of cognitive decline and to design timely interventions.

Another factor is white matter integrity (e.g., myelination, axonal density) which is affected by aging [106] impacting the efficiency of information transfer between brain regions and is associated with cognitive decline [107]. Gray matter is also impacted by aging and is typically reduced [108]. Disruptions in white matter and gray matter integrity can affect RSN connectivity. For example, in a study using fMRI and diffusion tensor imaging, Marstaller et al., 2015 [109] showed that compared to young adults, older adults recruited the salience and frontoparietal networks less consistently. Moreover, they showed that age-related decline in white matter integrity and gray matter volume was associated with activity in prefrontal nodes of the salience network and frontoparietal networks, possibly reflecting compensatory mechanisms [109].

Neuroinflammation in the brain could be a possible factor affecting FC in aging individuals [110]. Individuals with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) or mild cognitive impairment (MCI) have been shown to exhibit increased levels of inflammatory biomarkers [111], particularly in the frontotemporal regions which are associated with various cognitive functions, such as attention and working memory [112]. Vascular risk factors could also affect FC in aging individuals. For example, a longitudinal fMRI study involving cognitively unimpaired individuals at risk for AD found that higher cholesterol levels were associated with a reduction in DMN connectivity while higher diastolic blood pressure was associated with reduced global FC [113].

Age-related alterations in the brain’s FC vary among aging individuals and different factors could be attributed to such differences [94]. For example, aging females show higher functional connectivity within the DMN, whereas males show greater connectivity in the somatomotor network [71, 114]. Sleep dysfunction can alter resting-state networks [105]. For example, increased subjective sleep dysfunction and decreased fluid intelligence were associated with a shift in brain network dynamics. Brain states involving higher-order fronto-temporo-parietal networks increased, while lower-order visual networks decreased with age [12]. Some studies have even attributed human body size as a factor associated with within- and between-network resting-state FC [114, 115]. Genetics may also play a role in age-related functional changes in the brain. For example, the apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene which facilitates the synthesis of protein that helps transport fat in the blood and is a risk factor for Alzheimer’s, has been shown to affect FC in normal aging. Readers may refer to the following reviews on this topic [116, 117].

Having a poor lifestyle may also alter brain’s FC at rest. For example, regular physical exercise has been associated with increased resting-state FC in brain areas associated with higher-level cognitive functions including the hippocampus, frontal cortex, and basal ganglia by promoting neuroplasticity and enhanced blood flow [118]. Other modifiable lifestyle factors have also been shown to affect resting-state FC in aging such as caloric restriction [119], and social interactions [120].

Aging is associated with poor quality of sleep which [121] which is associated with cognitive decline [104] and may increase the risk of developing neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s [122, 123]. Particularly, several studies have reported decreased FC in various RSNs in Alzheimer’s [41, 42, 43, 44]. Such decreases in connectivity are typically interpreted as an impairment of the neural connections between functionally related brain regions [124]. In addition, studying RSN changes is crucial for understanding other neurodegenerative diseases [125] such as Parkinson’s disease (PD) [126, 127, 128], and frontotemporal dementia (FTD) [129, 130, 131]. RSNs have been shown to be altered even in degenerative myelopathy in patients with chronic non-traumatic spinal cord compression [132]. These diseases are characterized by progressive neuronal loss, synaptic dysfunction, and the accumulation of pathological proteins, which can significantly impact RSN connectivity and function. Early detection of RSN alterations may thus provide valuable insights into disease progression, facilitate differential diagnosis, and inform treatment strategies. Furthermore, RSN studies in aging and neurodegenerative diseases can contribute to our understanding of the brain’s compensatory mechanisms [38]. Uncovering these compensatory mechanisms could lead to the development of targeted interventions aimed at enhancing cognitive resilience and delaying the onset of cognitive impairment.

Understanding the electrophysiological underpinnings of RSNs is critical to understanding how the brain’s functional organization adapts to aging. Neuroimaging modalities including EEG and MEG, provide a more direct insight into the neural activity that underlies the spontaneous time-varying fluctuations observed in RSNs [133, 134]. As the brain ages, several electrophysiological changes occur that impact the characteristics of RSNs. One notable change is the alteration in oscillatory activity across different frequency bands. Studies have shown that there is a general decline in the power of Alpha (8–13 Hz) rhythms and an increase in Delta (2–4 Hz) and Theta (4–8 Hz) activity [135, 136, 137]. Interactions within different large-scale cortical networks might be indicated by power envelope correlations that are specific to certain frequencies [138].

Zhu et al., 2011 [139] studied causal connective networks across the cortex at different ages ranging from children to the elderly using resting-state EEG. They reported a decrease in asymmetry of the cortical interactive networks during aging with pronounced loss of functional connectivity in the left frontal and central brain areas [139]. Two prominent hypotheses could explain hemispheric asymmetry and aging: the right hemi-aging model, which posits a greater age-related cognitive decline in the right hemisphere [140], and the hemispheric asymmetry reduction in older adults (HAROLD) model, which suggests that frontal activity becomes less lateralized with age [141]. In another resting-state EEG study, Petti et al., 2016 [142] employed effective connectivity and graph theory to study differences in RSNs related to age. Their findings suggested that with normal aging, brain networks became more random and less structured. This was indicated by a decrease in connection weights, efficiencies, and clustering, along with an increase in characteristic path length. These changes denoted that “middle-aged” networks were less organized and exhibited lower power compared to those in younger individuals [142]. In another study utilizing resting-state MEG, Kida et al., 2023 [143], found a positive correlation between age and source power in the left frontal and temporal regions in the Beta frequency band. An increase in Beta power with aging has been reported in several MEG studies [144, 145, 146] and could be related to the compensatory process of hub aging [143].

Studying the brain’s resting state networks has gained popularity over the past two decades, particularly using fMRI which can non-invasively image the entire brain with high spatial resolution. This imaging modality has made it possible to study the brain structure and function from small regions to complex time-varying brain-wide interactions in normal aging and diseased populations. While currently, a significant number of research studies have interrogated normal aging processes, there are several challenges to understand and overcome before one can fully understand the brain’s resting-state networks in aging. For example, the fMRI BOLD signal is sensitive to several physiological processes such as heart pulsation and breathing which may affect psychological states such as anxiety [147]. Although several preprocessing tools can efficiently remove such physiological-related noise from the BOLD signal [148], the associated psychological state remains. It remains unclear how to exactly account for it in the analysis. Another challenge is a known problem in neuroscience studies which is low sample size leading to low statistical power. As a consequence, there is an overestimation of effect size and low reproducibility of results [149]. A recent study utilizing about 50,000 participants from publicly available datasets found that brain-wide studies require thousands of samples to obtain high reproducibility, whereas typical studies of such nature have only a few dozen participants. They found that in addition to false interpretation of results, such statistically underpowered studies could miss weaker but important associations [150]. As described above, there are several confounding factors that affect the aging resting-state networks such as genetics, lifestyle, social interactions, and diet. Therefore, the study should be designed carefully while taking these factors into account.

It is worth noting that fMRI has several inherent limitations. For example, fMRI measures the BOLD signal which is sensitive to cerebral oxygenation and is, therefore, not a direct measure of neuronal activity. Another issue with fMRI is cerebrovascular reactivity which in the context of fMRI BOLD signal refers to the capacity of blood vessels in the brain to respond to changes in carbon dioxide levels or other vasoactive stimuli. This response typically involves the dilation or constriction of blood vessels, which alters blood flow and, consequently, the local concentration of oxygenated versus deoxygenated hemoglobin. The BOLD signal in fMRI relies on these changes in blood oxygenation to infer neural activity [151]. Vascular reactivity may change with age or disease [152, 153]. One solution to this problem is to use multimodal imaging by incorporating MEG which is less sensitive to vascular reactivity compared to fMRI [152].

Moreover, the BOLD response is rather sluggish, i.e., in the order of seconds compared to the neuronal activity which is in the order of milliseconds [154]. This slow response prevents fMRI from studying fast brain dynamics. Imaging techniques with higher temporal resolution, for example, EEG which more directly interrogates neuronal activity have shown that the brain exhibits so-called “micro-states” on the order of milliseconds (about 100 ms) [155]. These microstates are sensitive to cognitive states and are altered in aging [156] and neuropsychiatric illnesses [157]. Moreover, the BOLD signal is primarily sensitive to the ferromagnetic deoxygenated hemoglobin [158], whereas recent studies employing brain-wide fNIRS [14] have shown differences in spatiotemporal properties of resting state networks between oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin states in healthy adults [13, 159]. Therefore, fMRI studies on aging may be supplemented with other imaging modalities such as EEG, MEG and fNIRS to understand the underlying aging processes more comprehensively with higher spatiotemporal resolution.

Additionally, it will be of benefit to design longitudinal studies (participants scanned at multiple time-points in life) to investigate the temporal trajectories of alterations in resting-state networks and to better distinguish the effects of confounding factors on the aging brain. Efforts such as the German 1000BRAINS project [160] and UK Biobank project [115], etc., enable studying participants longitudinally and could help in this direction. However, international collaborative efforts are needed to incorporate participants from a diverse population.

In this review, we summarized fMRI studies on age-related alterations in RSNs. Overall, functional connectivity is reduced globally, is reduced within-network, and increased between networks in aging individuals. While such connectivity changes are indicative of neural plasticity to restore normal function, the exact underlying mechanisms influencing such changes needs further clarification particularly using studies with a large sample size and adjustment for confounding factors. An in-depth understanding of age-related changes in RSNs may help develop effective interventions for age-related cognitive impairment and neurodegenerative diseases.

Conceptualization: AFK, NS & ZAS; Methodology: AFK, NS & ZAS; Literature review: AFK & NS; Original draft; AFK & NS. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

We are thankful to the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center for providing resources to write this paper. We are grateful for the helpful feedback from the reviewers.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.