1 Department of General Medicine, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Dalian Medical University, 116023 Dalian, Liaoning, China

Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a common central neurodegenerative disease disorder characterized primarily by cognitive impairment and non-cognitive neuropsychiatric symptoms that significantly impact patients’ daily lives and behavioral functioning. The pathogenesis of AD remains unclear and current Western medicines treatment are purely symptomatic, with a singular pathway, limited efficacy, and substantial toxicity and side effects. In recent years, as research into AD has deepened, there has been a gradual increase in the exploration and application of medicinal plants for the treatment of AD. Numerous studies have shown that medicinal plants and their active ingredients can potentially mitigate AD by regulating various molecular mechanisms, including the production and aggregation of pathological proteins, oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, apoptosis, mitochondrial dysfunction, neurogenesis, neurotransmission, and the brain-gut microbiota axis. In this review, we analyzed the pathogenesis of AD and comprehensively summarized recent advancements in research on medicinal plants for the treatment of AD, along with their underlying mechanisms and clinical evidence. Ultimately, we aimed to provide a reference for further investigation into the specific mechanisms through which medicinal plants prevent and treat AD, as well as for the identification of efficacious active ingredients derived from medicinal plants.

Keywords

- Alzheimer’s disease

- medicinal plants

- neuroprotection

- cognitive function

- neuroinflammation

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative condition characterized by cognitive deficits, behavioral abnormalities, and impaired social functioning, posing a significant global health threat to older adults and ranking as the fifth leading cause of death worldwide [1, 2]. According to a national cross-sectional study in 2020, approximately 9.83 million people aged 60 and above in China were affected by AD [3]. As the global population ages, the incidence, disability, and mortality rates of AD continue to rise annually, promising a growing burden on individuals, families, and societies in the future [4]. Clinical study has identified amyloid-

Currently, the drugs used in the treatment of AD primarily consist of cholinesterase inhibitors and N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonists [8], which can only partially improve the symptoms of patients, but do not reverse disease progression, and prolonged use can lead to various adverse effects. Additionally, surgical interventions used in clinical management are both risky and costly [9]. Hence, there is a critical need to further investigate the pathogenesis of AD and develop effective strategies for its prevention and treatment.

In traditional medical practices, numerous medicinal plants and their active ingredients have been recommended for enhancing cognitive function and alleviating symptoms of AD [10, 11], such as cognitive impairment, memory loss, spatial awareness deficits, depression, and dementia. Bioactive compounds derived from medicinal plants are noted for their low incidence of adverse effects and high effectiveness [12]. In recent years, a large number of scholars have carried out studies on active ingredients from medicinal plants for treating AD and elucidating their associated mechanisms [13, 14], thereby establishing experimental foundations for AD treatment using medicinal plants. Notably, Huperzine-A derived from Huperzia serrata has been clinically employed in the treatment of patients with AD [15, 16]. These findings underscored the potential of medicinal plants to offer novel perspectives and strategies for addressing AD in contemporary society.

Currently, there have been a scarcity of reviews focusing on plant-based bioactive compounds for the prevention and treatment of AD. This review provided a comprehensive overview of the current pathogenesis of AD. Furthermore, it summarized recent research on active ingredients derived from medicinal plants targeting AD through global and local databases such as PubMed, Web of Science, and China National Knowledge Infrastructure. The review examined the mechanisms and clinical efficacy of these compounds, aiming to inform the clinical application of medicinal plants in the treatment of AD and provide a theoretical basis for the development of new drugs to combat this disease.

This review article was conducted using electronic databases such as PubMed, Google Scholar, Springer Link, Science Direct, Cochrane Library, Embase, Web of Science, and Scopus. All published data till the year 2024 have been taken into consideration. The following search keywords were used in the search of materials for this study: “medicinal plants”, “active ingredients”, “bioactive compounds”, “polyphenols”, “flavonoids”, “alkaloids”, “terpenes”, “polysaccharides”, “quinones”, “glycosides”, “volatile oils”, “biological activity”, “pharmacological activities”, “Alzheimer’s disease”, “amyloid

Although AD was first reported by the German physician Alois Alzheimer more than 100 years ago [17], the precise mechanisms underlying its onset and progression remain unclear. Currently, the primary pathological feature of AD has been recognized as the deposition of extracellular amyloid

Furthermore, the formation of A

Increasing evidence has observed hyperphosphorylation of tau protein in the brain tissue of patients with AD [30], which in turn leads to the formation of intracellular neurofibrillary tangles, contributing to neuronal degeneration and eventual cell death. At a molecular level, cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (CDK5) can be activated by elevated levels of Ca2+ ions within neuronal cells. This activation accelerates microtubule depolymerization, causes cytoskeletal abnormalities, triggers microglial activation, and inflammation, and ultimately impairs neuronal function and leads to apoptotic cell death [31, 32].

Recent studies have also confirmed that viral infections [33], mitochondrial dysfunction [34], abnormalities in insulin signaling [35], imbalance in intestinal flora [36], excitotoxicity from amino acids [37], and deficits in cholinergic function [38] are closely associated with the progression of AD. These processes contribute to the aggregation of A

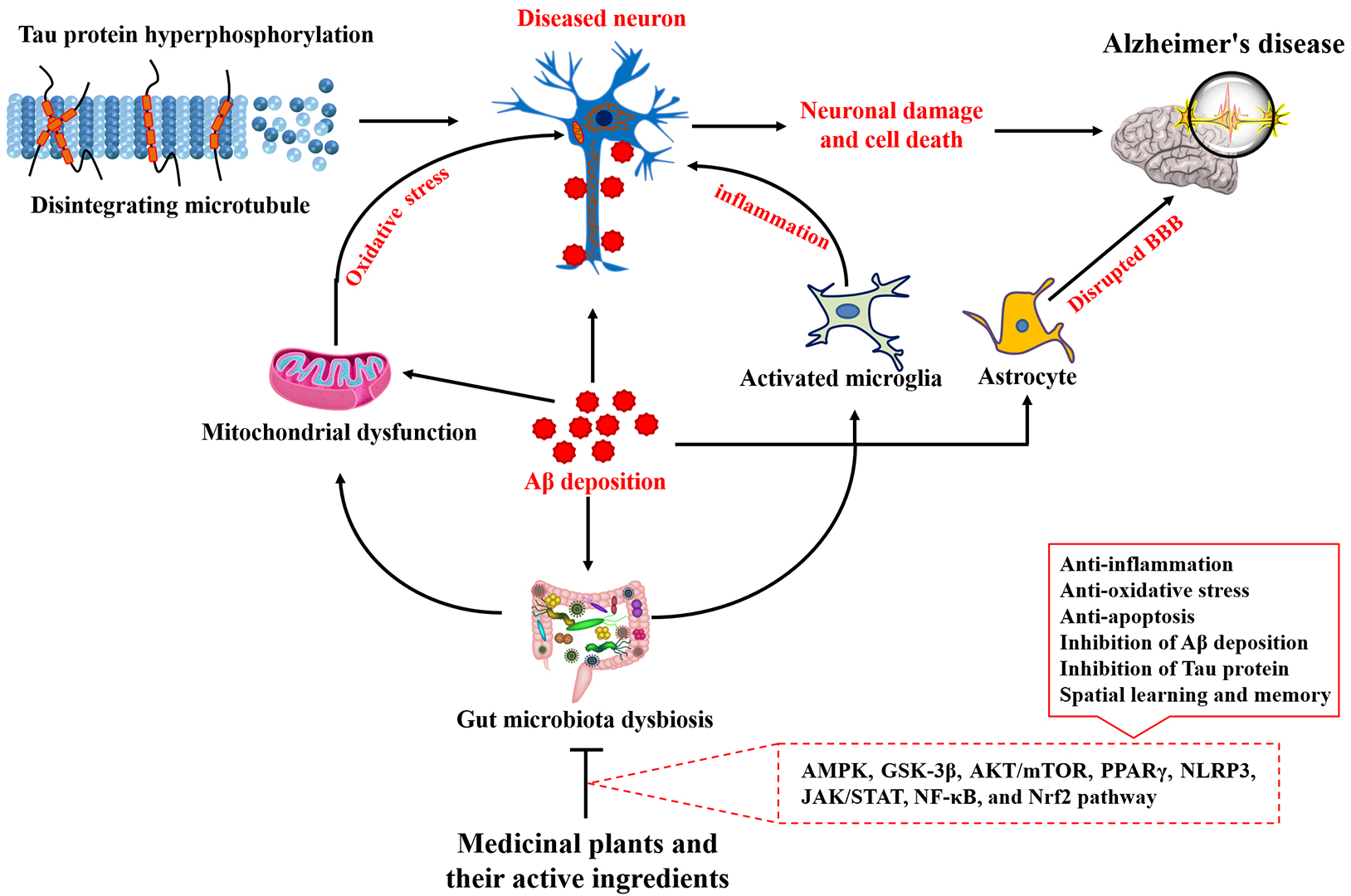

Through extensive research into the pathogenesis of AD, traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) has demonstrated unique therapeutic advantages in AD treatment due to its multi-component, multi-target approach, and emphasis on whole-body integrity [39]. Increasingly, a study has highlighted that medicinal plants and their primary bioactive constituents characterized by diverse structures, exert protective effects against neurodegenerative diseases [40]. The mechanisms by which plant-based bioactive compounds prevent AD are illustrated in Fig. 1 and detailed in Table 1 (Ref. [41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107, 108, 109, 110, 111, 112]). Meanwhile, the majority of Chinese AD patients have incorporated medicinal plants and herbal formulations into their diagnostic and treatment regimens [113, 114]. This review aimed to consolidate research progress on natural plant components in the treatment of AD, providing a reference for identifying safe and effective small molecules for AD treatment.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Therapeutic effects of medicinal plants and their main active ingredients on Alzheimer’s disease and the related mechanism. A

| Compound | Evaluation model | Effects and action mechanism | Ref. |

| Polyphenols | |||

| Paeonol | Behavioral dysfunction, A | [41] | |

| Rho/Rock2/Limk1/cofilin1 pathway ↑ | |||

| Carvacrol | Cell viability ↑ | [42] | |

| Memory impairment and oxidative stress ↓ | |||

| Pterostilbene | Neuronal plasticity, expression of SIRT1 and Nrf2, and SOD level ↑ | [43] | |

| Neuronal loss and mitochondria-dependent apoptosis ↓ | |||

| Learning and memory abilities ↑ | [44] | ||

| Microglial activation, A | |||

| Gastrodin | Inflammation and gut microbiota dysbiosis ↓ | [45] | |

| Expression of ZO-1 and occludin ↑ | |||

| Ellagic acid | Learning and memory abilities and level of SOD and CAT ↑ | [46] | |

| MDA level ↓ | |||

| Salidroside | Cognitive dysfunction, A | [47] | |

| TLR4/NF- | |||

| Cognitive impairment, A | [48] | ||

| Nrf2/GPX4 pathway ↑ | |||

| Resveratrol | NLRP3 inflammasome and NF-ĸB pathway ↓ | [49] | |

| Expression of CAT and SOD2 ↑ | |||

| Curcumin | Cognitive function, spatial memory, SOD content, and AMPK pathway ↑ | [50] | |

| Damaged neurons and levels of A | |||

| EGCG | Cognitive impairment, Tau phosphorylation, and expression of A | [51] | |

| Ach content ↑ | |||

| Kaempferol | Cell death and apoptosis ↓ | [52] | |

| ERS/ERK/MAPK pathway ↓ | |||

| Learning and memory abilities, and expression of GAD67 and p‑NMDAR ↑ | [53] | ||

| Quercetin | Cognitive function and A | [54] | |

| Tau phosphorylation ↓ | |||

| Cell proliferation and levels of SOD, GSH-Px, CAT, and Nrf2 protein ↑ | [55] | ||

| Levels of LDH, AChE, MDA, and HO-1 protein ↓ | |||

| Flavonoids | |||

| Genistein | A | [56] | |

| Autophagy and TFEB ↑ | |||

| Learning and memory ability ↑ | [57] | ||

| Neuronal damage and ERS-mediated apoptosis ↓ | |||

| Amentoflavone | Neurological dysfunction and pyroptosis ↓ | [58] | |

| AMPK/GSK-3 | |||

| Q3GA | Neuroinflammation, A | [59] | |

| CREB and BDNF levels ↑ | |||

| Naringenin | Levels of ULK1, Beclin1, ATG5, and ATG7 ↑ | [60] | |

| A | |||

| Rutin | Tau aggregation, inflammation, microglial activation, and NF-κB pathway ↓ | [61] | |

| PP2A level ↑ | |||

| DHMDC | Learning and memory abilities, and GSH activity ↑ | [62] | |

| Lipid peroxidation, TBARS level, and AChE activity ↓ | |||

| Isoorientin | Levels of IL-4 and IL-10 ↑ | [63] | |

| A | |||

| Trilobatin | Memory impairment, A | [64] | |

| TLR4-MYD88-NF-κB pathway ↓ | |||

| Eriodictyol | Cognitive deficits, A | [65] | |

| Nrf2/HO-1 pathway ↑ | |||

| Quercitrin | Microglia activation, inflammation, and A | [66] | |

| Hesperidin | A | [67] | |

| Neural stem cell proliferation and AMPK/CREB pathway ↑ | |||

| Icariin | Memory deficits, A | [68] | |

| Brain glucose uptake, NeuN, and AKT/GSK-3 | |||

| Content of A | [69] | ||

| Learning and memory abilities, synaptic plasticity, and BDNF-TrκB pathway ↑ | |||

| Dihydromyricetin | Inflammation, cell apoptosis, and level of TLR4 and MD2 ↓ | [70] | |

| Silibinin | Cognitive impairment and inflammatory cytokines ↓ | [71] | |

| Level of SLC7A11 and GPX4 ↑ | |||

| Nobiletin | Memory defects, A | [72] | |

| SIRT1/FoxO3a pathway ↑ | |||

| Luteolin | Memory impairment, A | [73] | |

| PPAR | |||

| Baicalein | Cognitive and memory impairment ↓ | [74] | |

| Synaptic plasticity and AMP/GMP-CREB-BDNF pathway ↑ | |||

| Learning and memory abilities ↑ | [75] | ||

| Neuroinflammation and CX3CR1/NF-κB pathway ↓ | |||

| Alkaloids | |||

| Oxymatrine | Neuronal damage, microglia activation, levels of TNF- | [76] | |

| NF-κB and MAPK pathways ↓ | |||

| Isorhynchophylline | Cognitive deficits, A | [77] | |

| Rutaecarpine | Learning and memory deficits and tau hyperphosphorylation ↓ | [78] | |

| Synaptic plasticity ↑ | |||

| Tetrandrine | Cognitive ability ↑ | [79] | |

| A | |||

| Sophocarpine | Cognitive impairment, A | [80] | |

| Rhynchophylline | A | [81] | |

| Homoharringtonine | Cognitive deficits, A | [82] | |

| DMTHB | Cognitive deficits, microglia activation, and NLRP3 inflammasome ↓ | [83] | |

| Magnoflorine | Cognitive deficits, cell apoptosis, ROS generation ↓ | [84] | |

| JNK pathway ↓ | |||

| Dauricine | Learning and memory deficits, neuronal damage, expression of p-CaMKII, p-Tau, A | [85] | |

| Berberine | Cognitive disorders, A | [86] | |

| Nrf2 pathway ↑ | |||

| Terpenes | |||

| Oleanolic acid | Cell viability and expression of stanniocalcin-1 ↑ | [87] | |

| ROS level and A | |||

| Artemisinin | Cognitive impairment, A | [88] | |

| ERK/CREB pathway ↑ | |||

| NeuN+ cells ↑ | [89] | ||

| Inflammation and NF-κB pathway ↓ | |||

| Linalool | Neurodegeneration, ROS levels, oxidative stress, and inflammatory response ↓ | [90] | |

| Tanshinone IIA | Spatial learning, memory deficits, A | [91] | |

| Synapse-associated proteins (Syn and PSD-95) ↑ | |||

| RAGE/NF-κB pathway ↓ | |||

| Bilobalide | A | [92] | |

| Geniposidic Acid | Cognitive impairment, A | [93] | |

| GAP43 expression and PI3K/AKT pathway ↑ | |||

| Ginkgolide | Levels of TNF- | [94] | |

| NF-κB pathway ↓ | |||

| Cucurbitacin B | Cognitive impairment, neuron apoptosis, and inflammation ↓ | [95] | |

| Ginkgolide B | Cognitive behavior and | [96] | |

| Pro-inflammatory cytokines and NLRP3 inflammasome ↓ | |||

| OABL | Cognitive function ↑ | [97] | |

| Neuroinflammation, A | |||

| Ginsenoside Rg1 | Cognitive impairment, p-Tau, A | [98] | |

| Activity of SOD, CAT, GSH-Px ↑ | |||

| Artesunate | Deficits in memory and learning, A | [99] | |

| Celastrol | Memory dysfunction, cognitive deficits, p-Tau ↓ | [100] | |

| TFEB ↑ | |||

| Patchouli alcohol | Cognitive defects, A | [101] | |

| Microglial phagocytosis and synaptic integrity ↑ | |||

| BDNF/TrkB/CREB pathway ↑ | |||

| Paeoniflorin | Cognitive ability and SOD expression ↑ | [102] | |

| Cell ferroptosis ↓ | |||

| Catalpol | Levels of A | [103] | |

| Astragaloside IV | Microglial activation, inflammation, and EGFR pathway ↓ | [104] | |

| Polysaccharides | |||

| Coptis chinensis | Cell viability ↑; Oxidative stress and JNK pathway ↓ | [105] | |

| Lycium barbarum | A | [106] | |

| Angelica sinensis | Learning and memory deficiency, AchE level, MDA, and inflammation ↓ | [107] | |

| Activity of SOD and CAT and BDNF/TrkB/CREB pathway ↑ | |||

| Codonopsis pilosula | Cognitive defects and expression of A | [108] | |

| Synaptic plasticity ↑ | |||

| Astragalus membranaceus | Apoptosis of brain cells and content of A | [109] | |

| Spatial learning and memory abilities and Nrf2 pathway ↑ | |||

| Taxus Chinensis | Cognitive defects, level of caspase-3, Bax, MDA, ROS, and A | [110] | |

| Level of SOD and Nrf2 pathway ↑ | |||

| Cistanche deserticola | Memory and learning disorders, inflammation, and gut microbiota dysbiosis ↓ | [111] | |

| Polygonatum sibiricum | Cell death, memory impairment, oxidative stress, and inflammation ↓ | [112] | |

Note: AchE, Acetylcholinesterase; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; AMPK, adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase; A

Polyphenols are widely found in grapes, Salvia miltiorrhiza, tea, Gastrodia elata, and other medicinal plants. Modern pharmacological study has confirmed that polyphenolic compounds have a variety of biological activities [115], including antitumor, antioxidant, anti-inflammation, and anti-oxidative stress properties. Importantly, increasing study has confirmed the anti-AD potential of polyphenolic compounds [116], with their mechanisms summarized in Table 1. For example, proanthocyanidins, a type of polyphenolic compound, possess a spectrum of biological activities that impede the onset and progression of AD [117, 118], including anti-inflammatory effects, improvement of insulin resistance, and anti-oxidative stress properties. Resveratrol, capable of crossing the blood-brain barrier, exerts neuroprotective effects by reducing glial activation, amyloid precursor protein levels, and plaque formation [119], and by modulating gut microbiota composition [120] in AD treatment. Research by Fasina et al. [45] has demonstrated that gastrodin enhances memory function in AD mouse models by targeting the “gut microbiota-brain” axis, attenuating neuroinflammation, and preserving intestinal barrier integrity. Other studies have indicated that pterostilbene possesses neuroprotective properties against AD through its anti-inflammatory activities and mitigation of mitochondria-dependent apoptosis [43, 44]. Additionally, ferulic acid has been shown to ameliorate AD progression by reducing the accumulation of A

Flavonoids, secondary metabolites widely found in medicinal plants, exhibit various pharmacological activities beneficial to human health [122], including their role in treating AD (Table 1). Previous studies have demonstrated that compounds like nobiletin [72] and luteolin [73] exert anti-AD effects by inhibiting oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and neuroinflammation. Sun et al. [61] have shown that rutin mitigates AD progression by reducing tau aggregation, neuroinflammation, and tau oligomer-induced cytotoxicity. Icariin [123] and genistein [57] have been found to ameliorate memory impairment in AD mouse models by suppressing endoplasmic reticulum stress. Quercetin-3-O-Glucuronide, a type of active flavonol glucuronide, exhibits anti-neuroinflammatory effects in AD by modulating the gut microbiota-brain axis, as evidenced by its ability to reduce short-chain fatty acids and address gut microbiota dysbiosis [59]. Overall, flavonoids possess a diverse array of biological activities that can prevent the development and progression of AD.

Alkaloids, a class of nitrogen-containing basic organic compounds widely found in medicinal plants, exert protective effects against AD by suppressing inflammation, oxidative stress, and neuronal apoptosis (Table 1). Matrine, a natural quinolizidine alkaloid isolated from Sophora flavescens, reduces proinflammatory cytokines and A

Terpenoids, a diverse group of organic compounds found in medicinal plants, are increasingly recognized for their potential in treating various diseases [126, 127]. Their preventive and therapeutic effects on AD have garnered significant attention (Table 1), owing to their remarkable biological activities, such as anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anti-apoptotic properties. Huperzine-A, a natural sesquiterpene alkaloid derived from Huperzia serrata, demonstrates a neuroprotective effect in AD by reducing A

Currently, plant polysaccharides have been gaining significant global attention due to their versatile biological activities, including antioxidation, anti-inflammation, and anti-oxidative stress properties, coupled with minimal side effects [132]. Particularly noteworthy are their potential roles in mitigating risk factors associated with AD [133] (Table 1), such as modulation of neuroplasticity, promotion of neurogenesis, normalization of neurotransmission, and suppression of neuroinflammation. For instance, Angelica polysaccharides have been shown to alleviate AD progression by reducing inflammation, oxidative stress, neuronal apoptosis, and improving memory impairment [107]. Polysaccharides from Coptis chinensis protect A

In addition to the previously mentioned compounds isolated from medicinal plants for the prevention of AD, various other plant-based bioactive compounds have shown therapeutic potential against AD. Studies have highlighted that quinones such as sennoside A [134], rhein [135], and shikonin [136], phenylpropanoids, including magnolol [137] and forsythoside A [138], glycosides such as tenuifolin [139] and ginsenoside compound K [140], and volatile oils from plants like Acorus tatarinowii Schott [141], Rosmarinus officinalis and Mentha piperita oils [142], alleviate AD progression through antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-apoptotic activities. Furthermore, several medicinal plants have demonstrated potential in preventing or treating AD, including Moringa oleifera [143], Rosmarinus officinalis [144], Nardostachys jatamansi [145], and Tinospora cordifolia [146]. For example, plant-derived alkaloids [147, 148], polyphenols [149], flavonoids [150, 151], saponins [152, 153], alkaloids [154], terpenes [155], and essential oils [156, 157] showed multi-targeted activity against acetylcholinesterase, butyrylcholinesterase, tyrosinase, monoamine oxidase, and pancreatic lipase, which helped to prevent the occurrence and development of AD. However, the functional roles of these plant-based bioactive compounds in the treatment of AD remain poorly understood, with limited knowledge of their mechanisms. In conclusion, plant-based bioactive compounds exhibit multi-target and versatile biological activities in experimental AD studies, suggesting their potential as therapeutic agents for AD treatment in clinical settings.

Accumulating evidence indicates that medicinal plants offer a wide range of pharmacological effects in AD, with beneficial efficacy demonstrated in vitro cell models and animal experiments. Gul et al. [158] have reported that Huperzine-A acts as an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, improving cognition and task-switching abilities in patients with AD. Moreover, ongoing clinical studies are exploring the safety and efficacy of medicinal plant decoctions and injections for the treatment of AD (Table 2). A randomized controlled clinical trial found that Di-Tan decoction is a safe method for treating AD and improving cognitive symptoms [159]. Another study demonstrated that a medicinal plant formula was beneficial for cognitive improvement in AD patients by reducing A

| Sources | Year of registration | Enrollment | Sponsor | Clinical trial ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yizhi Baduanjin | 2023 | 30 | The University of Hong Kong, China | NCT06453941 |

| Rhizoma acori Tatarinowii, Poria cum Radix Pini, and Radix polygalae | 2022 | 180 | Peking Union Medical College Hospital, China | NCT05538507 |

| Centella asiatica | 2022 | 48 | Oregon Health and Science University, USA | NCT05591027 |

| Yangxue Qingnao Pills | 2021 | 216 | Dongzhimen Hospital, China | NCT04780399 |

| Yi-gan-san, Huan-shao-dan, Salvia miltiorrhiza, Rhizoma gastrodiae, Ramulus uncariae cum Uncis, and Morindae officinalis | 2020 | 28 | Taipei Veterans General Hospital, China | NCT04249869 |

| Bupleurum+Ginkgo | 2019 | 60 | Xuanwu Hospital, China | NCT04279418 |

| GRAPE granules | 2017 | 120 | Dongzhimen Hospital, China | NCT03221894 |

| Jian Pi Yi Shen Hua Tan Granules | 2016 | 300 | Dongfang Hospital Beijing University of Chinese Medicine, China | NCT02641886 |

| Ginkgo biloba Extract | 2016 | 240 | The First Affiliated Hospital with Nanjing Medical University, China | NCT03090516 |

| EGb761® | 2008 | 49 | Ipsen, France | NCT00814346 |

| Nootropics (Ginkgo biloba, nicergoline, piracetam, or others) | 2006 | 1134 | Janssen-Cilag G.m.b.H, USA | NCT01009476 |

| Curcumin and Ginkgo | 2004 | 36 | Chinese University of Hong Kong, China | NCT00164749 |

| Curcumin | 2003 | 33 | John Douglas French Foundation, USA | NCT00099710 |

| Ginkgo biloba | 2000 | 3069 | National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, USA | NCT00010803 |

However, it is also necessary to explore the several challenges of translating preclinical findings into clinical applications. The biggest challenge to plant-based drug delivery into the brain is circumventing the blood-brain barrier, which prevents the entry of numerous potential therapeutic agents. Another challenge is related to approval of the drug for commercialization because enough resources are unavailable. Since some compounds cannot be synthesized in a semi-synthetic manner or by growing or engineering the plant artificially, this will increase the product’s dependency on natural resources. As per the reports, nearly 25,000 plants will go extinct, which imposes an ethical issue for extracting bioactive compounds from plants. In addition, there is still a lack of sufficient clinical data and their mechanisms of action. Finally, plant-based bioactive compounds have solubility & absorption, intellectual property, absence of drug-likeness, and purity issues.

Medicinal plants have been used for thousands of years and have been broadly used in clinical practice in China and several other Asian countries (such as Japan and Korea) [165], and Chinese people have a wealth of clinical experience in medicinal plants. Currently, medicinal plants account for more than 40% of China’s pharmaceutical market [166]. Meanwhile, the world health organization (WHO) stated that about 80% of the world population depends on medicinal plants to satisfy healthcare requirements [167, 168]. For example, Evalvulus alsinoides, Centella asiatica, Myristica fragrans, Andrographis paniculata, Nardostachys jatamansi, and Nelumbo nucifera widely used in Indian traditional medicine systems for cognitive enhancement were known for their acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activity [169]. Lobbens et al. [170] reported that a total of 29 ethanolic extracts from European traditional medicine plants served as new drug candidates for the treatment of AD by inhibition of acetylcholinesterase and amyloidogenic activities. Kumar et al. [171] found that medicinal plants from the Australian rainforest possessed anti-AD activity by suppressing neuroinflammation. In the West Africa region, over 10,000 medicinal plants have been utilized in curing neurodegenerative diseases [172], such as Pyllanthus amarus, Crysophyllum albidum, Rauwolfia vomitora, Abrus precatorius. A clinical study confirmed that administration with ninjin’yoeito (NYT), a traditional Japanese medicine (Kampo medicine), improved impairments and depressive states in twelve AD patients [173]. Meanwhile, Ginkgo biloba extract (EGb 761®) was registered as an ethical drug in Western countries and has been widely used in clinical therapy to treat AD [174]. Galantamine (Razadyne®) serves as a selective competitive and reversible inhibitor of acetylcholinesterase and has received regulatory approval in 29 countries [175], such as Sweden, Austria, United States, Europe, and other countries. Rivastigmine (Exelon®) was approved to treat mild to moderate AD in over 40 countries in North and South America, Asia, and Europe [176]. Currently, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved tacrine (Cognex®), donepezil (Aricept®), galantamine, memantine, and rivastigmine for the treatment of AD patients in clinical [177, 178]. Taken together, medicinal plant-based bioactive compounds exhibited their powerful roles in the management of AD progression and helped to relieve the symptoms related to AD.

With increasing research into the pathogenesis of AD, the role of medicinal plants in its treatment has advanced significantly in recent years. TCM has been particularly prominent in treating various diseases, including AD, and offers a new perspective in the modern era for both the prevention and treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). This review underscored that plant-based bioactive ingredients can prevent and manage AD through multiple mechanisms, including reducing the production and aggregation of pathological proteins, enhancing their degradation, antioxidative and anti-inflammatory activities, improving mitochondrial function and energy metabolism, regulating intestinal flora, inhibiting neuronal apoptosis, and promoting neurogenesis. Clinical trials have demonstrated the efficacy and safety of medicinal plants in alleviating the symptoms of AD. However, the treatment of AD with medicinal plant-based bioactive ingredients still faces some challenges that must be addressed. (1) With the rapid development of science, there is a need to elucidate the physiological functions and mechanistic explanations of medicinal plants against AD using network pharmacological approaches and multi-omics techniques, such as nutrigenomics, metabolomics, proteomics, gut microbial macrogenomics, and immunomics. (2) Further validation of the metabolic, toxicity, and pharmacokinetic profiles of medicinal plants in clinical trials for AD is essential. (3) Research on active ingredients from medicinal plants is limited by unstable chemical structures, low bioavailability, and susceptibility to oxidation. Consideration of strategies like liposome embedding or nanoparticle formulation may mitigate these challenges. (4) Many active compounds from medicinal plants cannot effectively cross the blood-brain barrier to reach the brain. Exploring how plant-based bioactive compounds that regulate intestinal flora based on the “brain-gut microbiota” axis can mitigate AD is warranted.

Due to the synergistic effects, systematic analytical tools must be developed to study the multi-component, multi-rule, and multi-target characteristics of TCM. Network-based approaches in medicinal plants use computational algorithms to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of bioactive compounds and identify the underlying synergistic effects. Moreover, the development of network pharmacology diminishes the cost, reduces the risk, and saves time in researching new bioactive compounds for the treatment of various diseases, including AD [179]. Researchers can use these tools and experimental knowledge to determine effective substances in medicinal plants for AD. For example, Wu et al. [180] presented a novel algorithm based on entropy and random walk with the restart of the heterogeneous network was proposed for predicting active ingredients for AD and screening out the effective TCMs for AD, and results showed that the top 15 active ingredients may act as multi-target agents in the prevention and treatment of AD, Danshen, Gouteng and Chaihu were recommended as effective TCMs for AD, Yiqitongyutang was recommended as effective compound for AD. Recent studies have proved that integrating network pharmacology and experimental verification to reveal the potential pharmacological ingredients and mechanisms of different medicinal plants (Paeonia lactiflora [181], Acoritataninowii rhizome [182], Ginkgo biloba [183], Panax ginseng [184], Corydalis rhizome [185]) in curing AD, and TCM decoction (Erjingwan [186], Jin-Si-Wei [187], Guhan Yangshengjing [188], and Tian-Si-Yin [189]). Therefore, using network pharmacology to discover the relationship between medicinal plants, AD, and cellular responses was easily achievable.

In conclusion, medicinal plants exhibit promising anti-AD effects and serve as essential active agents for treating neurodegenerative diseases. In addition to experimental studies, bioinformatics approaches provide valuable insights into the mechanisms by which plant-based bioactive compounds exert their therapeutic effects on AD. Incorporating molecular docking studies, molecular dynamics simulations, quantitative structure-activity relationship models, network pharmacology, and genomics/transcriptomics analyses can significantly enhance our understanding of the multi-target effects and potential efficacy of these compounds. Integration of these bioinformatics methods could validate experimental findings and guide the development of novel therapeutic strategies for AD. This review synthesized the current understanding of AD’s pathogenesis, systematically analyzed and explored the mechanisms of medicinal plants in preventing AD, and reviewed their clinical trial outcomes. The aim was to offer a scientific and comprehensive reference for the treatment of AD with medicinal plants, enhancing the utilization and development of TCM resources.

AchE, acetylcholinesterase; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; AMPK, adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase; A

DC and YS conceptualized and designed the study. DC designed the figures and conducted a literature review. Both authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. Both authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.