1 The First Clinical Medical College, Gansu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Gansu Provincial Hospital), 730000 Lanzhou, Gansu, China

2 School of Clinical Medicine, Ningxia Medical University, 750000 Yinchuan, Ningxia, China

3 Department of Radiology, Gansu Provincial Hospital, 730000 Lanzhou, Gansu, China

Abstract

Background and Purpose: To investigate the abnormal pattern of altered functional activity in the brain and the neuroimaging mechanisms underlying the cognitive impairment of patients with colorectal cancer (CRC) via resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI). Materials and Methods: CRC patients (n = 56) and healthy controls (HCs) (n = 50) were studied. The participants underwent rs-fMRI scans and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA). The amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations (ALFF), degree centrality (DC), regional homogeneity (ReHo), and MoCA scores, were calculated for participants. Results: The scores of executives, visuospatial, memory, language and attention were lower in CRC patients. ReHo and ALFF values in the left postcentral gyrus, ReHo values in the right postcentral gyrus, ALFF and DC values in the left middle occipital gyrus, ReHo and DC values in the right lingual gyrus, DC values in the right angular gyrus and precuneus, and ALFF values in the left middle temporal gyrus decreased conspicuously in the CRC patients. Conclusion: CRC patients have abnormal resting state function, mainly in the brain areas involved in cognitive function. The overlapping brain regions with abnormal functional indicators are in the middle occipital gyrus, postcentral gyrus, and lingual gyrus. This study reveals the potential biological pathways involved in brain impairment and neurocognitive decline in patients with CRC.

Keywords

- colorectal cancer

- degree centrality

- amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations

- regional homogeneity

- functional brain activity

In 2020, Global Cancer Statistics demonstrated that the global prevalence and mortality rate of patients with colorectal cancer (CRC) rank 3rd and 2nd, respectively, with the prevalence of CRC in China rapidly increasing (ranking 2nd) [1]. Research has revealed that cognitive impairment affects nearly 45% of CRC patients [2], and there are no effective therapies to prevent cognitive dysfunction [3]. In CRC patients, cognitive impairment leads to the development of attention deficits, working memory issues, difficulties in verbal learning and memory, and reduced speed of processing complex tasks [4]. Disruption of cognitive function and brain structure can decrease the patients’ quality of life. However, brain impairment and cognitive decline in CRC patients are often detected in late stages, which makes it difficult to treat. This is greatly because the mechanism underlying cognitive impairment neuropathology is unknown.

Resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI) technology [5] has been in general use in recent years to study neuropsychiatric disorders [6, 7]. The standard indices employed in rs-fMRI include the amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations (ALFF) [8], degree centrality (DC) [9], and regional homogeneity (ReHo) [10]. ALFF measures resting-state blood oxygen level-dependent signal fluctuations in the brain, providing detailed measurements of the intensity of spontaneous brain activity with extraordinary sensitivity and precision [11]. ReHo uses Kendall’s harmony coefficient to measure the similarity of a given voxel’s time series to its 28 neighboring voxel time series, illustrating the synchronization of both global and regional brain functions with the voxel’s functional role [12]. DC explores the abnormal functional connections of the whole brain through voxel-based whole-brain correlation analysis based on graph theory, which can quantify the importance of each node in the brain functional network [13]. These three voxel-based rs-fMRI indexes determine the operational traits of the brain from multiple viewpoints and can be used effectively to study changes in brain functional activities [14, 15, 16]. To the best of our understanding, only a few of studies have used any of these indices to investigate brain function in CRC patients [17, 18, 19]. Nonetheless, those few studies have provided inconsistent results, necessitating a multi-index combined investigation.

Contemporary research indicates a consistent association between impaired cognitive function and anomalies in the functional activity of brain regions within the default mode network (DMN) [20, 21, 22], which regulates diverse cognitive domains such as self-reference, episodic memory, social cognition, mind wandering, semantic and verbal memory [23, 24]. Considering the observed cognitive impairments in CRC patients, we speculate that abnormal functional activity in DMN-associated brain regions among these individuals. We hypothesize that such alterations in spontaneous neural activity may indeed correlate with cognitive function in this population.

A total of 26 CRC patients were retrospectively recruited from September 2018 to

June 2021, and 42 CRC patients were prospectively recruited from August 2021 to

May 2023, from the Department of Anorectal Surgery of

Gansu Provincial Hospital. Meanwhile, 70 healthy controls (HC)

were prospectively recruited through advertising. Inclusion criteria were: (1)

Subjects were aged 18–60 years; (2)

This study was performed in compliant with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Gansu Provincial Hospital (approval numbers: 2015–154, 2023–004). All participants completed written informed consent forms.

Clinical data, including sex, age, educational level, and history of surgery or chemotherapy were recorded. The cognitive abilities of all participants were assessed using MoCA. The MoCA allows for quick screening of mild cognitive impairment in the cognitive areas of visuospatial/executive, attention, memory, language, abstraction, arithmetic, and orientation. Scale assessments were performed on the day magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans were executed.

Cranial MRI scan examination was conducted using a 3.0T magnetic resonance

scanner (MAGNETOM Skyra, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) equipped with a

32-channel phased-array head coil. Briefly, the subjects were placed in a supine

position, and were told to relax as much as possible, avoid focused thinking

activities, and remain awake. Sponge pads were used to minimize head movements,

and the subjects wore headphones or earplugs to minimize noise. Brain MRI image

was acquired by two specially trained radiologists. Conventional cranial MRI

scans were performed first, to exclude intracranial organic lesions, followed by

three-dimensional high-resolution T1WI (3D T1-weighted imaging, 3D-T1WI) and

rs-fMRI imaging. Scanning parameters: (1) A 3D magnetization-prepared

gradient-echo sequence was used to scan 3 D-T1WI structural images (slice

thickness = 1.33 mm; number of slices = 144; slice gap = 0.665 mm; Repetition

Time (TR)/Echedelay Time (TE) = 2530/2.35 ms; 256

The MRI-image data were preprocessed using SPM12

(http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm) and DPABI_V6.2

(http://rfmri.org/DPABI) software, based on Matrix Laboratory platform

as follows: (1) DICOM-image format conversion, dislodge of the first 10 time

points, slice time correction, and head movement correction (excluding subjects

with mean-frame-wise displacement (FD)-Jenkinson

The time series of each voxel was transformed into the frequency range using the Fast Fourier Transform method after preprocessing. The power spectrum of each frequency was obtained, and its square root was determined. The mean of all square root values represented the ALFF value.

The consistency of the time series of neuronal activity between voxels of the whole brain and the neighboring voxels was assessed with Kendall’s harmony coefficient. The Kendall’s harmony coefficient for each voxel of the whole brain was calculated to obtain the individual-level Kendall’s harmony coefficient map of each participant’s ReHo map. A standardized ReHo brain map was established by dividing the ReHo values for each voxel of the whole brain by the average ReHo values of all voxels. Finally, smoothing was processed (Gaussian kernel of Full Width at Half Maximum: 6 mm), followed by statistical analysis.

A Pearson correlation analysis between any set of gray matter voxels time series in the brain was performed using DPABI software to obtain the connectivity map of the whole brain functional network. The weakly correlated voxels associated with noise signals or white matter were eliminated at the r = 0.25 threshold. Finally, the DC values were normalized to a matrix image conforming to a normal distribution and used for statistical analysis after Gaussian smoothing.

SPSS 26.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all data analyses.

All clinical data were assessed for normality and homogeneity

of variances. Two sample t-tests were used to analyze differences in age and

years of education, Mann-Whitney U-test was employed to compare differences in

MoCA scores between the two groups, and Chi-square test was performed to estimate

the differences in sex. Statistical significance was defined at

p

Two sample t-tests were used to compare ALFF, ReHo, and DC values using

the statistical module of DPABI software. Sex, age, years of education, surgery,

chemotherapy, and head movement parameters were used as covariates.

The significance threshold was established as p

Finally, Spearman correlation analyses were performed to investigate whether the

ALFF, ReHo, and DC values of brain regions demonstrating

group-differences were correlated with the scores of MoCA and the subdomain. The

salience threshold was established as p

Eleven CRC patients and 9 HCs were excluded during MRI scanning due to

intracranial organic lesions or physical reasons. Moreover, 1 CRC patient and 8

HCs were excluded from MRI scanning due to head movement overload during image

preprocessing, and 3 HCs were excluded because the MoCA scores

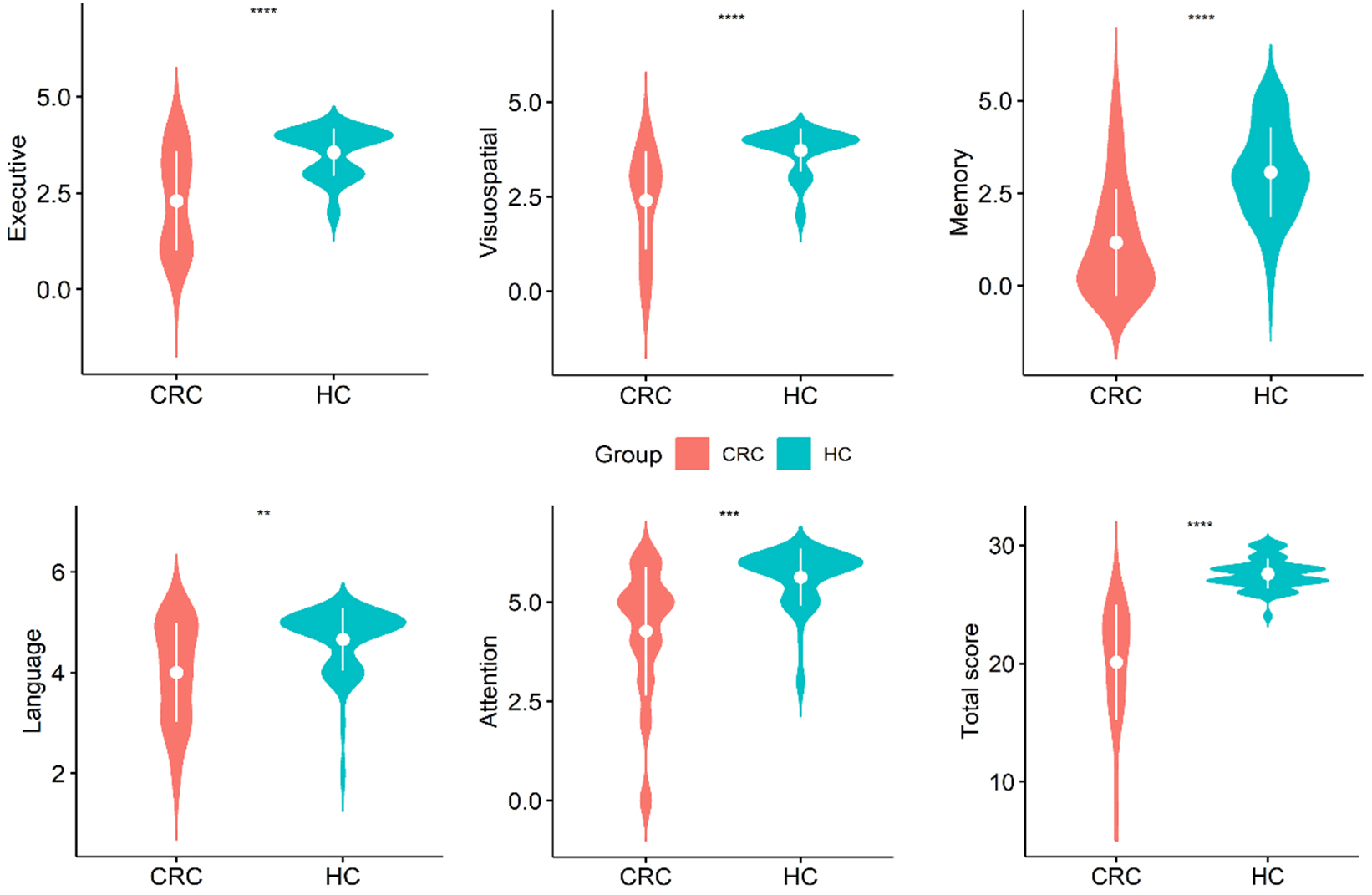

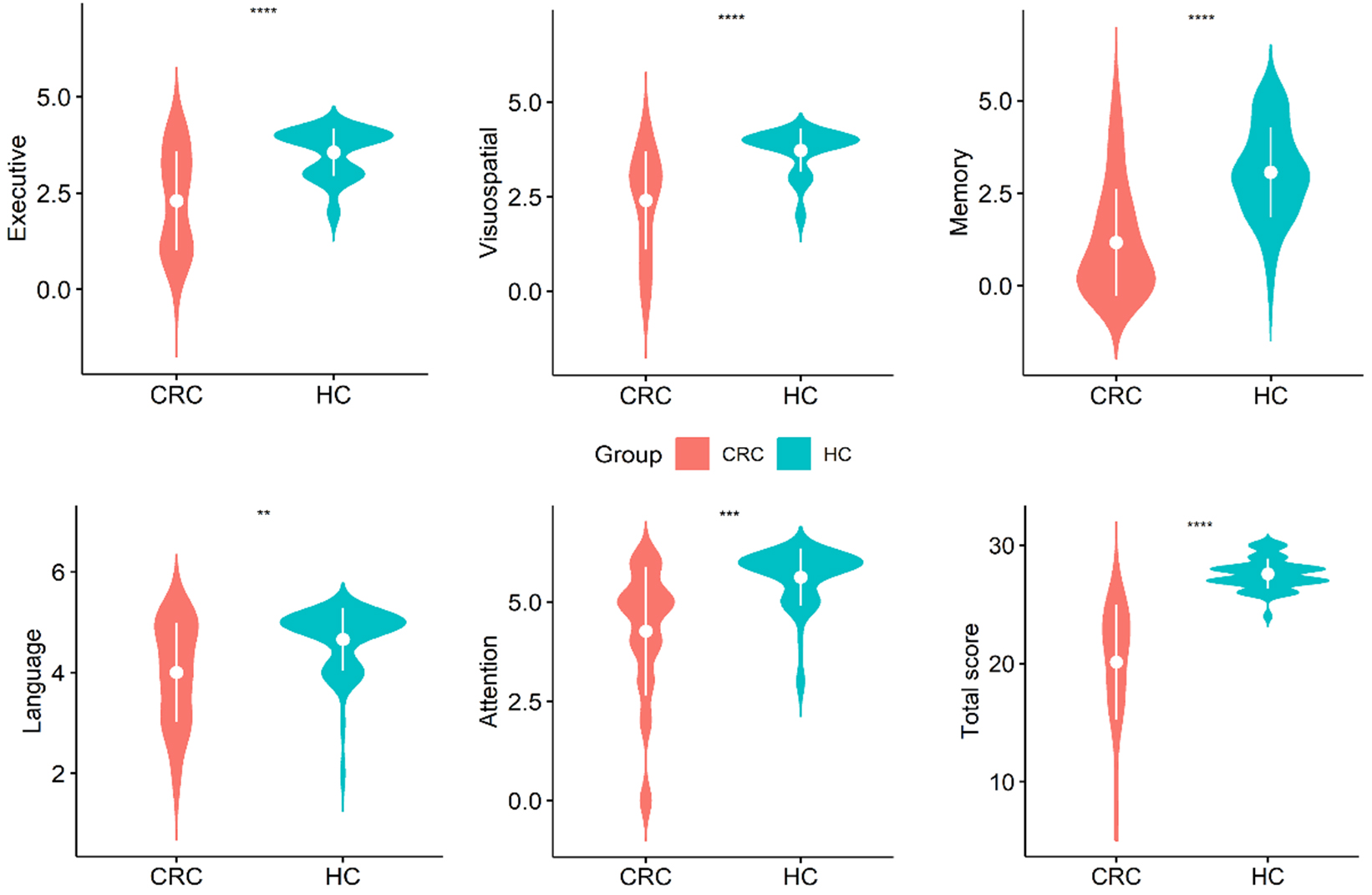

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Violin plots of the distribution of data for

each MoCA subdomain score within the group. **p

| Demographic clinical data | CRC group | HCs group | χ2/t/Z values | p | |

| (n = 56) | (n = 50) | ||||

| Age (years) | 50.00 |

47.46 |

1.89 | 0.061 | |

| Sex (M/F) | 30/26 | 28/22 | 0.06 | 0.802 | |

| Education (years) | 10.79 |

12.36 |

–2.41 | 0.018* | |

| Surgery (%) | 20 (36%) | - | - | - | |

| Chemotherapy (%) | 16 (29%) | - | - | - | |

| Chemotherapy (rounds) | n | - | - | - | |

| 1 |

11 | - | - | - | |

| 4 |

4 | - | - | - | |

| 7 |

1 | - | - | - | |

| Time since diagnosis (month) | n | - | - | - | |

| 7 | - | - | - | ||

| 2 |

41 | ||||

| 4 |

8 | - | - | - | |

| △MoCA (%) | 30/56 (53%) | 50/50 (100%) | - | - | |

| MoCA (score) | 22.00 (5.00, 25.50) | 27.50 (24.00, 30.00) | –10.32 | ||

| Executive | 2.50 (0.00, 4.00) | 4.00 (2.00, 4.00) | –4.45 | ||

| Visuospatial | 3.00 (0.00, 4.00) | 4.00 (2.00, 4.00) | –5.45 | ||

| Memory | 1.00 (0.00, 5.00) | 3.00 (0.00, 5.00) | –5.12 | ||

| Language | 4.00 (2.00, 5.00) | 5.00 (3.00, 5.00) | –3.27 | 0.001* | |

| Attention | 5.00 (0.00, 6.00) | 6.00 (3.00, 6.00) | –4.86 | ||

Normally distributed continuous variables as mean

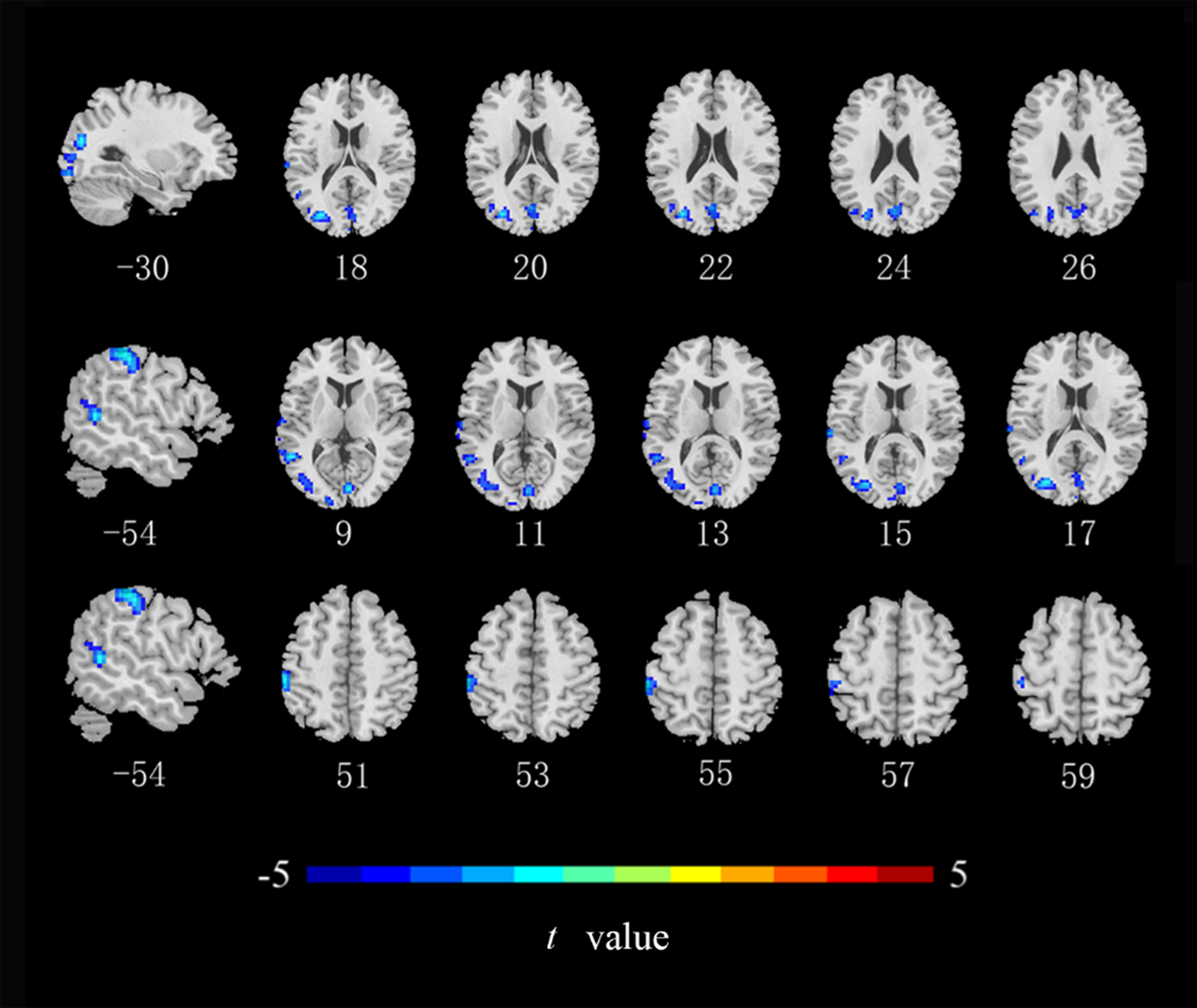

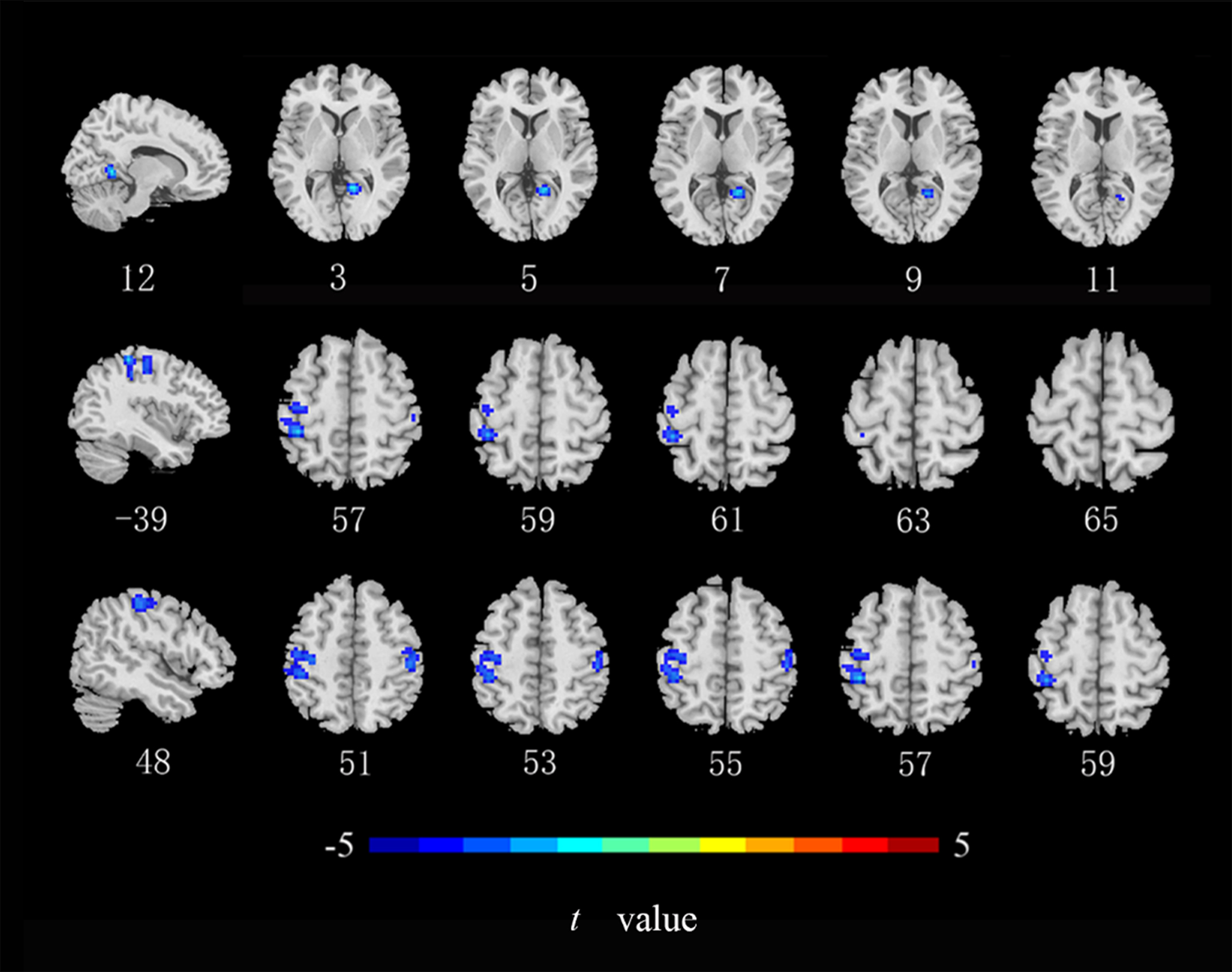

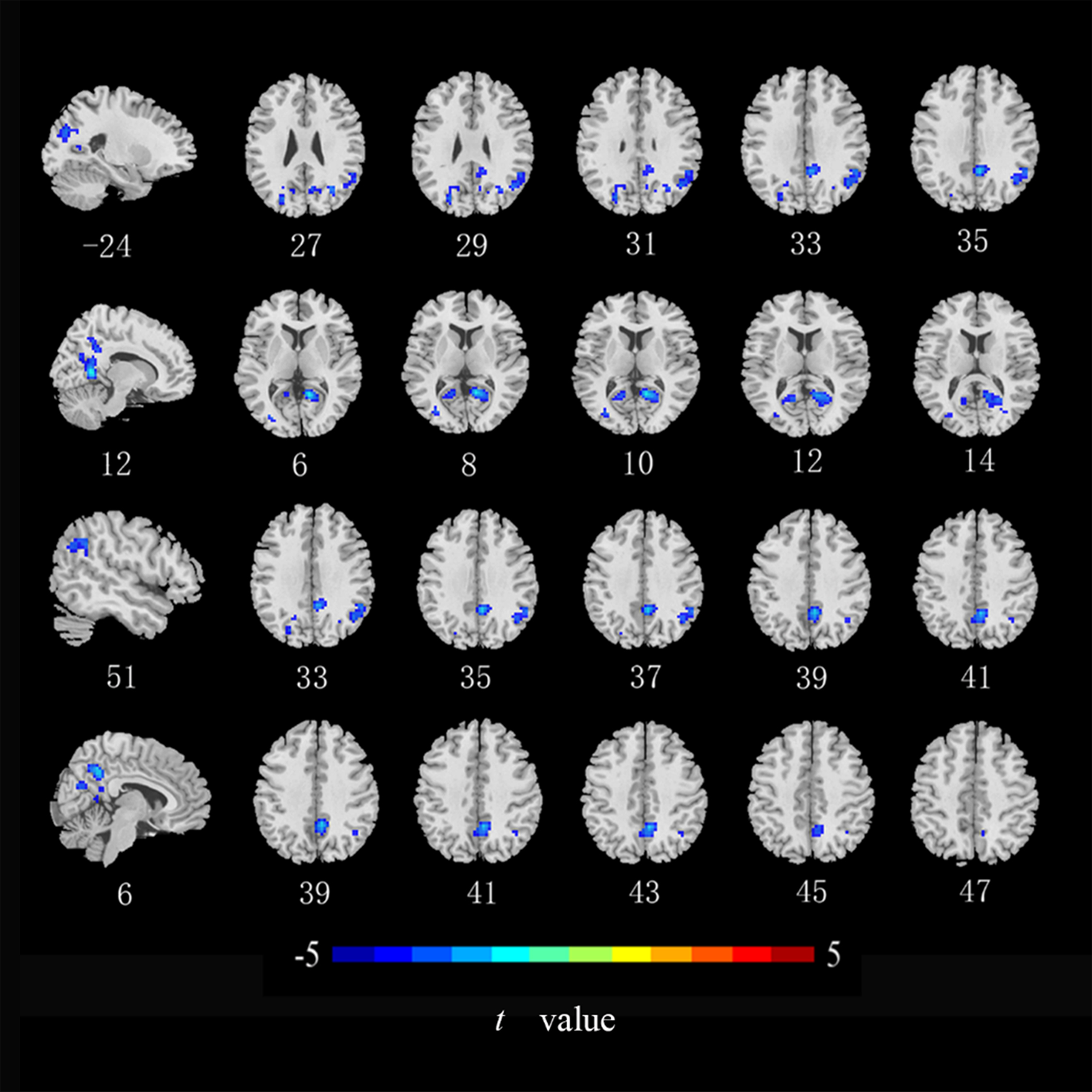

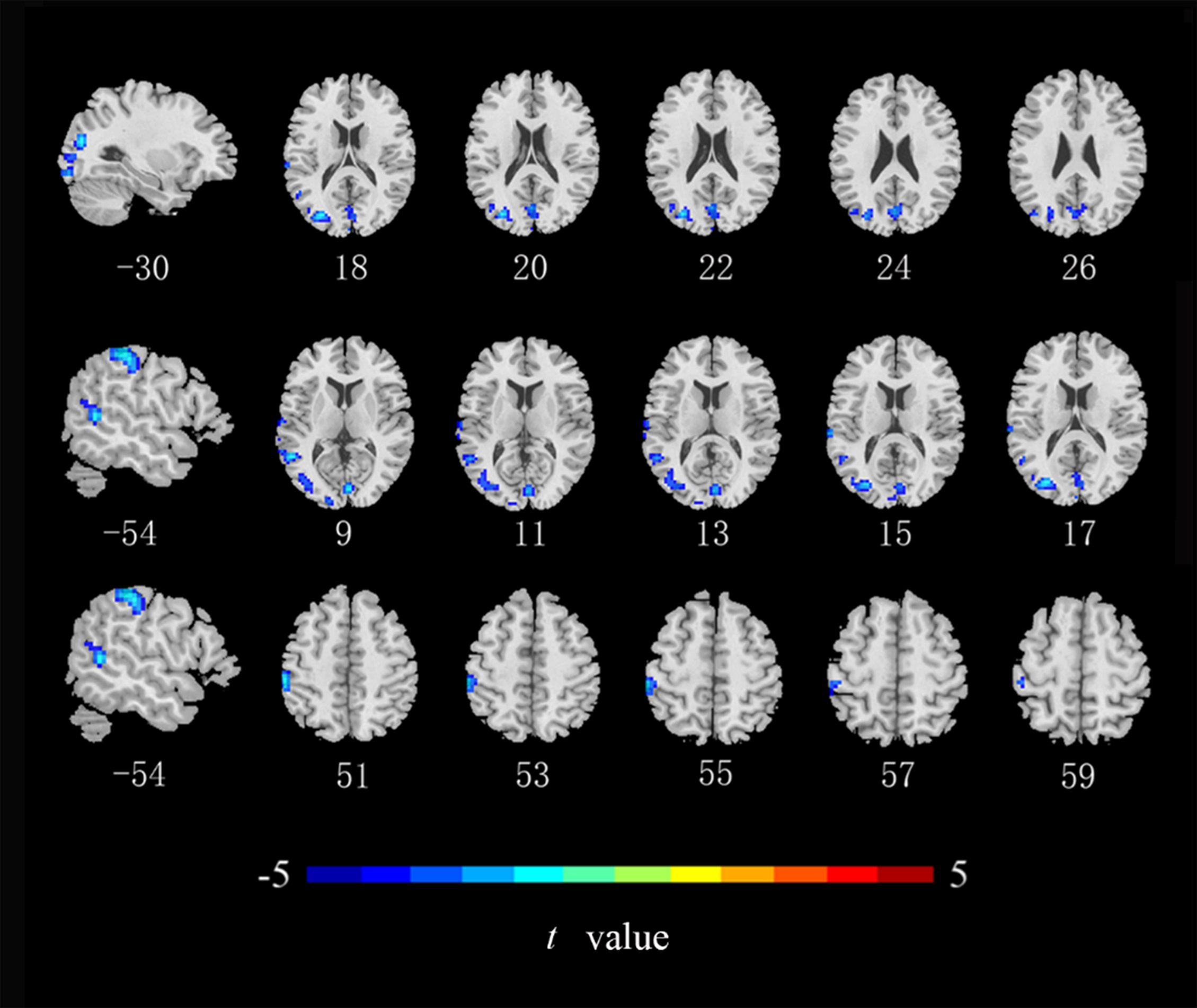

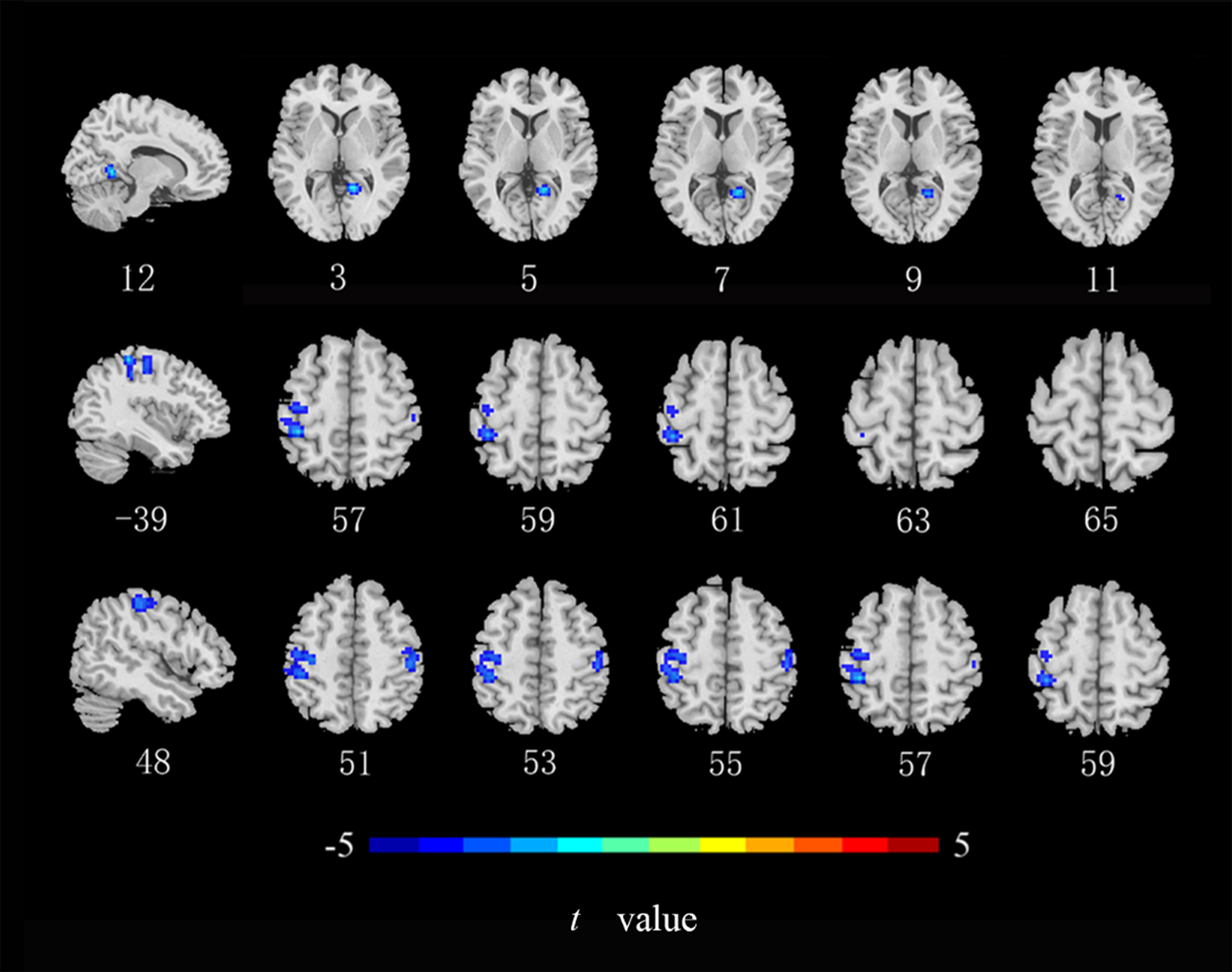

Compared with the HCs, ALFF values in the left middle occipital gyrus, middle temporal gyrus, and postcentral gyrus (Fig. 2), ReHo values in the right lingual gyrus and bilateral postcentral gyrus (Fig. 3), and DC values in the left middle occipital gyrus, right lingual gyrus, precuneus, and angular gyrus were lower in the CRC patients (Fig. 4). Notably, ALFF, ReHo, and DC values were not increased in any brain region. Differences in brain regions of CRC patients that showed effects are shown in Table 2.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Brain regions of CRC patients that showed a significantly lower

ALFF index than did those in healthy controls. ALFF, amplitude of low-frequency

fluctuations (cluster level p

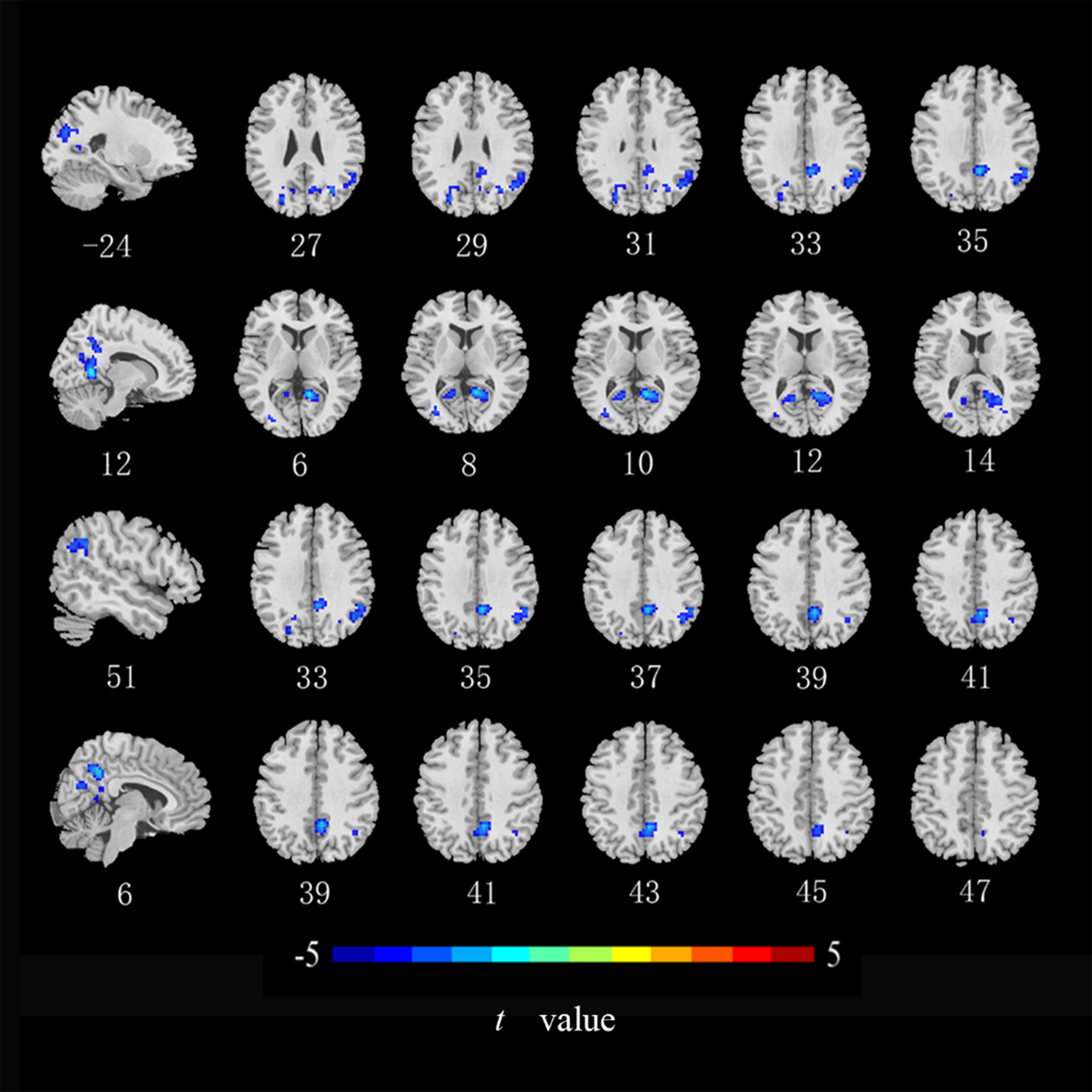

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Brain regions of CRC patients that showed a significantly lower

ReHo index than did those in healthy controls. ReHo, regional homogeneity

(cluster level p

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Brain regions with of CRC patients that showed a significantly

lower DC index than did those in healthy controls. DC, degree

centrality (cluster level p

| Index | Brain regions (AAL) | MNI coordinates | Voxel size | T value of Peak | ||

| X | Y | Z | ||||

| ALFF | MOG_L | –30 | –78 | 18 | 512 | –4.881 |

| MTG_L | –54 | –51 | 9 | 132 | –4.850 | |

| Postcentral gyrus _L | –54 | –30 | 51 | 126 | –4.863 | |

| ReHo | Lingual gyrus _R | 12 | –51 | 3 | 70 | –6.160 |

| Postcentral gyrus _L | –39 | –36 | 57 | 293 | –5.264 | |

| Postcentral gyrus _R | 48 | –27 | 51 | 67 | –4.519 | |

| MOG_L | –24 | –75 | 27 | 147 | –4.518 | |

| DC | Lingual gyrus _R | 12 | –54 | 6 | 267 | –6.259 |

| Angular gyrus _R | 51 | –48 | 33 | 114 | –4.632 | |

| Precuneus _R | 6 | –51 | 39 | 108 | –5.767 | |

MOG_L, left middle occipital gyrus; MTG_L, left middle

temporal gyrus; ALFF, amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations; DC, degree

centrality; ReHo, regional homogeneity; AAL, Automatic Anatomical Labeling

Template; MNI, Montreal Neurological Institute (voxel level p

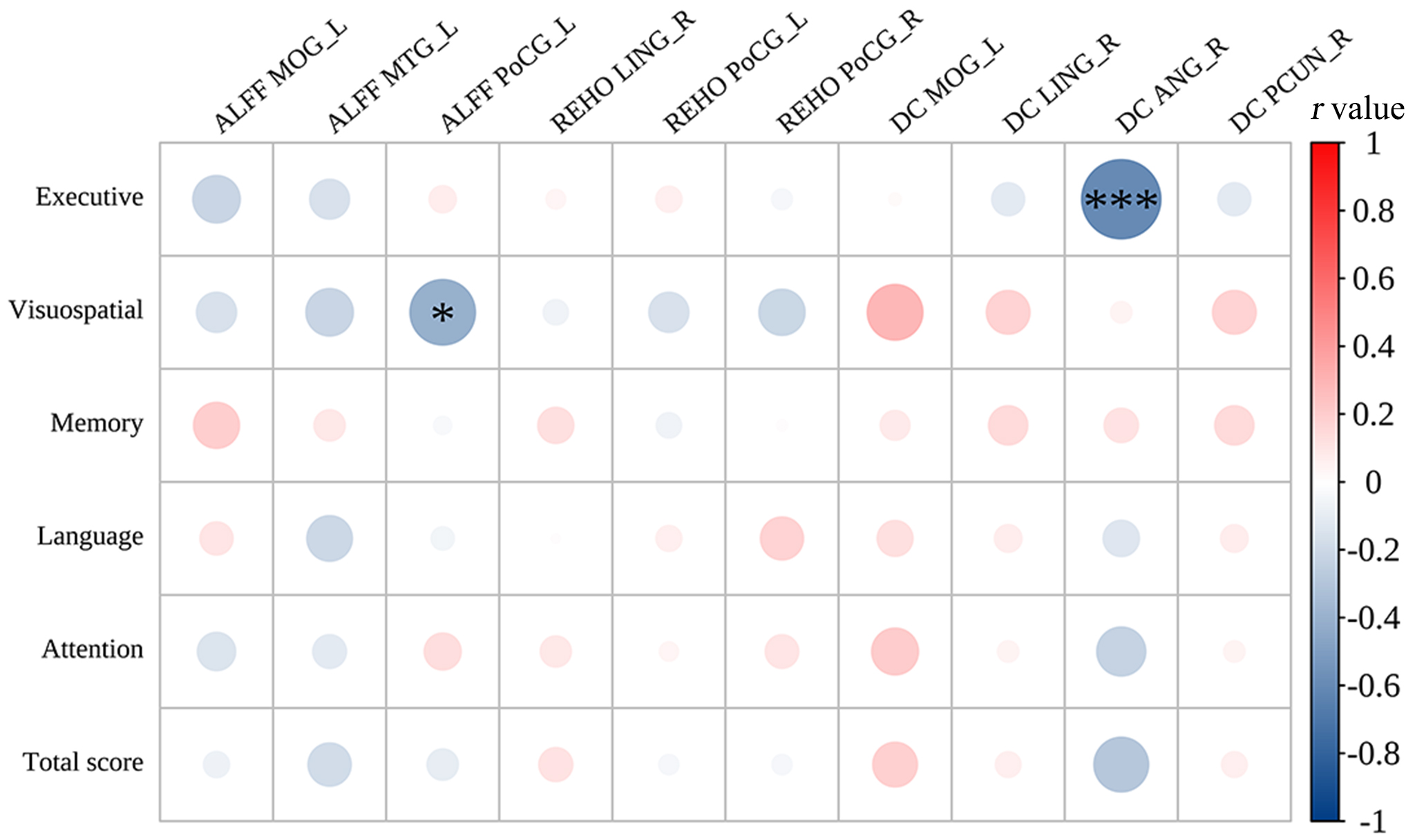

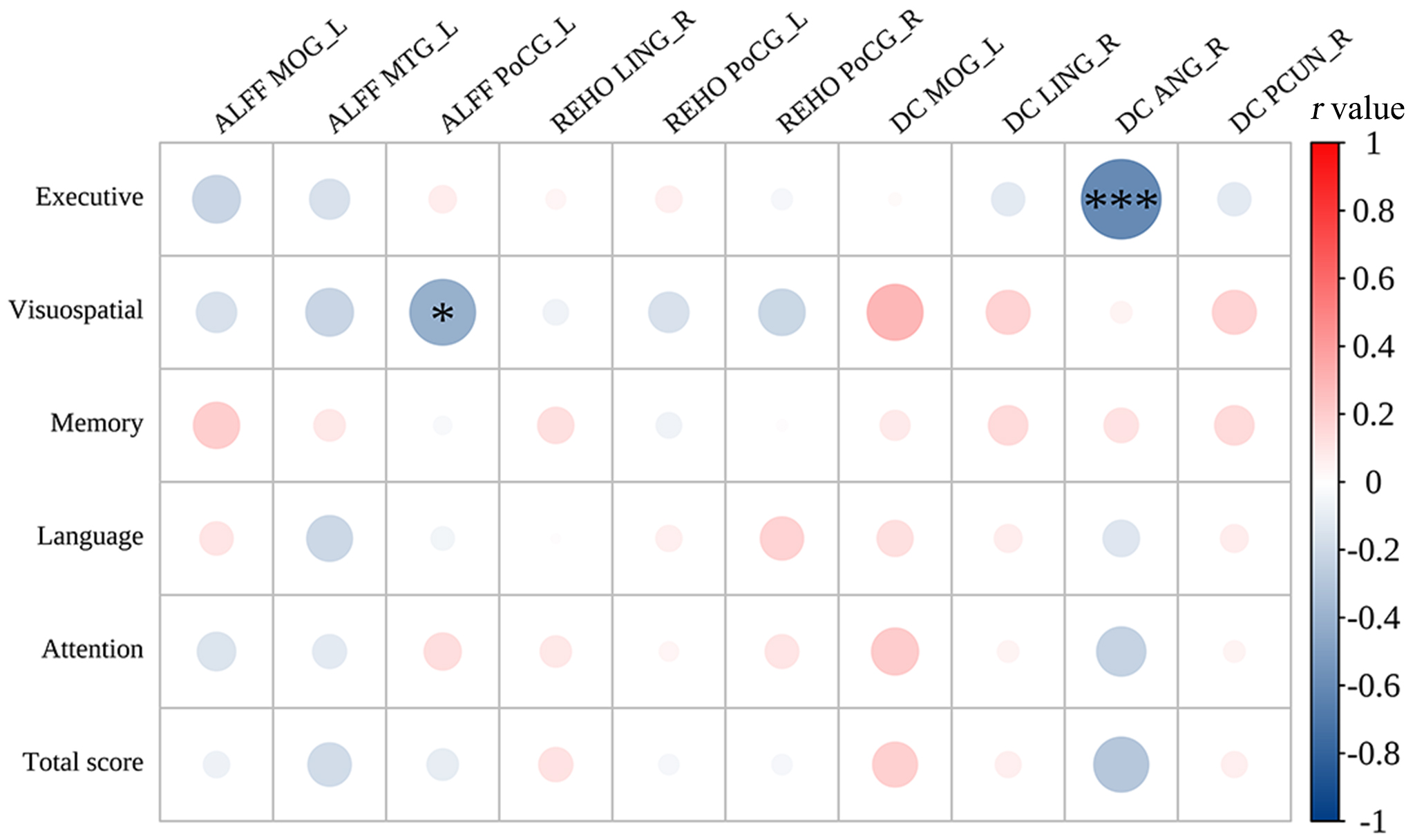

The left postcentral gyrus ALFF values were negatively

correlated with the visuospatial scores subdomain of the MoCA (r = –0.406,

p = 0.026) and the right angular gyrus DC values were negatively

correlated with the executive scores (r = –0.596, p

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Correlations between cognitive scores and the abnormal brain regions in CRC patients. ALFF, amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations; DC, degree centrality; ReHo, regional homogeneity; MOG_L, left middle occipital gyrus; MTG_L, left middle temporal gyrus; PoCG_L, left postcentral gyrus; PoCG_R, right postcentral gyrus; LING_R, right lingual gyrus; ANG_R, right angular gyrus; PCUN_R, right precuneus. *r = –0.32, ***r = –0.67.

This study aimed to investigate abnormal functional activity patterns in brain regions in CRC patients using three whole-brain resting-state functional indices (ALFF, ReHo, and DC) combined with MoCA scale scores. The results indicated that CRC patients had lower cognitive function scores compared to HCs. Furthermore, CRC patients exhibited abnormal brain functional activity in regions linked with the DMN, including the right precuneus, left middle temporal gyrus, and right angular gyrus. Unexpectedly, reduced functional brain activity was also found in the sensorimotor network (bilateral postcentral gyrus) and visual network (left middle occipital gyrus and right lingual gyrus) in CRC patients. These findings suggest that cognitive brain function is impaired in colorectal cancer patients and that the reduced functional activity in these patients may not be limited to the default mode network.

According to a previous study [25], the MoCA test has been subdivided into distinct domains, each associated with specific cutoff values that demonstrate sensitivity and specificity in evaluating cognitive function. These cutoff values facilitate the identification of cognitive impairment among patients. Violin plots and scatter plots (Fig. 1) were utilized to visually depict the scores of patients across each subdomain and to compare them with those of healthy individuals. The findings reveal that patients scored significantly lower than controls in various cognitive domains, including executive function, visuospatial abilities, memory, language, and attention, as well as in the overall MoCA score. These results are consistent with prior research findings.

In this study, 73% of the patients were 2–3 months post-diagnosis during the trial. A minority of patients underwent surgery (36%) and chemotherapy (29%). Many chemotherapy patients received three or fewer cycles, that a lower number of chemotherapy rounds may have a lesser impact on patients. Therefore, the altered brain activity and cognitive decline in patients is likely attributed to the disease itself. It is important to interpret these results cautiously due to the lack of pre- and post-surgery/chemotherapy comparisons. Future longitudinal studies with a larger patient sample are needed to delve deeper into the mechanisms of cognitive impairment in colorectal cancer patients.

The surgical patients were scanned and evaluated 30 days or more after surgery, they stated that they recovered well after surgery, with no incision pain and no obvious physical discomfort. Most chemotherapy patients experience nausea and vomiting on the day after chemotherapy. Our experiment was conducted before this chemotherapy, and the time since the last chemotherapy was greater than or equal to 21 days. The patients had no discomfort during the examination. As time goes by, after diagnosis, surgery and chemotherapy, the patients gradually accepted their disease status, cooperated with the treatment with a cheerful outlook, and tried to eat foods with high nutritional value. Therefore, the patients with colorectal cancer did not lose significant weight. Based on the above analyses of patient treatment factors, pain, and nutritional status, we think that changes in functional brain activity and reduced cognitive function scores in cancer patients may not be related to these factors, in our study. Of course, longitudinal studies with larger sample sizes are needed to explore the dynamic changes in brain functional activity and cognition in patients with colorectal cancer.

Compared with those of HCs, CRC patients exhibited lower DC values in the precuneus and angular gyrus, as well as lower ALFF values in the left middle temporal gyrus. The angular gyrus, precuneus, and middle temporal gyrus are all crucial components of the DMN [20, 26, 27]. The precuneus is associated with self-awareness, and it is known as the ‘mind’s eye’ [28]. The angular gyrus and the precuneus are in the parietal lobe; they have functions related to situational and semantic memory [29, 30]. Notably, studies have displayed that the effectiveness of the nodes in the functional network of the right precuneus is significantly lower in CRC patients [19], consistent with the present study. The angular gyrus and the precuneus are the central nodes of the DMN and key hubs of brain tissue (from a network perspective) [24, 31]. The default-mode network is intricately linked to environmental monitoring, conscious arousal, emotional processing, self-reflection, and situational memory [32, 33]. In the present study, brain regions in the DMN were impaired in CRC patients, indicating the potential neuropathological mechanism for their cognitive decline. One study showed that breast cancer patients exhibit abnormal mean fractional ALFF changes in the right angular gyrus [34]. Besides, activating the dorsal angular gyrus through transcranial magnetic stimulation enhances cognitive function in individuals with mild cognitive impairment [35]. These findings suggest that the angular gyrus leads to higher-order cognitive processing. Nevertheless, alterations in the DC value of the right angular gyrus were negatively correlated with scores on the MoCA subdomains related to executive function. The precise neural mechanisms driving this relationship remain uncertain. Therefore, detailed subgroup analyses are necessary to investigate the impact of altered brain function on cognitive performance in CRC patients. Taken together, these results show that the precuneus and the angular gyrus may be useful imaging markers for the detection of cognitive impairment in CRC patients.

The middle temporal gyrus is in the temporal lobe and plays a crucial role in language processing (regulating grammatical information), memory encoding, and executive functioning [36, 37]. One study suggested that damage to the middle temporal gyrus may promote the development of mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease [38]. In this study, CRC patients exhibited lower executive function scores and decreased ALFF in the left middle temporal gyrus. These findings indicate that patients with CRC exhibit aberrant neural activity in the middle temporal gyrus during resting states. However, we acknowledge that a direct correlation between this abnormal activity and executive function has not been firmly established. Thus, caution is warranted when interpreting the potential implications of abnormal functional activity in the middle temporal gyrus for executive function in CRC patients.

Furthermore, we observed overlaps between brain areas with ALFF, ReHo, and DC abnormalities, including the middle occipital gyrus, postcentral gyrus, and lingual gyrus. These findings demonstrate that CRC patients may have abnormal low spontaneous activity in specific brain regions. The lingual gyrus and the middle occipital gyrus are associated with visual episodic memory and short-term memory deficits, which are part of the visual network, are located in the occipital lobe [39]. In our study, we discovered that CRC patients had lower spontaneous brain activity in these areas and had significantly lower visuospatial/executive function scores compared to the HCs. This suggests that impairment in these brain areas may affect the processing of visual stimuli and consequently impact the patients’ visuospatial/executive functions. However, there was no correlation between the impairment in these brain areas and other cognitive functions in our study. Therefore, further research is needed to explore this speculation. Moreover, the results revealed lower DC values in the middle occipital gyrus and lingual gyrus among CRC patients, signifying diminished functionality of these brain regions as central nodes. This decline in function could potentially exert indirect effects on cognitive functions in other brain regions.

In the context of large-scale brain networks, the postcentral gyrus is considered as a component of the sensorimotor network. The postcentral gyrus houses the primary and secondary somatosensory cortex, which is take charge for processing and encoding sensory information, as well as contributing to higher-level cognitive functions including memory [40]. In the study, we found that CRC patients showed lower ReHo and ALFF values in the postcentral gyrus, along with lower memory scores compared to HCs. However, no correlation was found between abnormal brain functional activity and memory scores. Further research is required to explore this relationship. Voxel-mirrored homotopic connectivity is reduced in the postcentral gyrus of breast cancer patients [41], suggesting that the postcentral gyrus of cancer patients may be vulnerable. Furthermore, research has revealed an interaction between non-CNS cancers and brain [42]. Abnormal local functional activity of the middle occipital gyrus, lingual gyrus, and postcentral gyrus occurs in patients with various diseases, including CRC [18, 43], lung cancer [44], in young cancer patients [45], in breast cancer [41, 46, 47] and leukemia [48]. Therefore, cancer may cause abnormal functioning in certain brain areas [49], consistent with these study results. In this study, indicators of abnormal functioning of the posterior central gyrus correlated with visuospatial scores, suggesting that abnormal to the posterior central gyrus can have a detrimental effect on visuospatial. Therefore, in future studies, it is imperative to enroll more participants to discover the interaction between abnormal functional activity in brain regions and cognitive function in CRC patients.

The highlight of this study is the use of the combination of ALFF, ReHo, and DC indices to explore the changes in brain function in CRC patients. However, several limitations remain in the study. First, although the sample size is comparable to, or larger than, that of previous research using similar methods, a larger sample size is necessary. Second, although “years of education” was used as a covariate to remove as much bias as possible, there was a difference in education level between CRC patients and HCs, and thus results should be carefully interpreted. Third, although the participants were asked not to focus on any specific mental activity while undergoing the rs-fMRI scan, and each participant’s wakefulness was verified at the end of the scan, it was difficult to control for individual differences in resting-state thought processes.

Abnormal resting-state functional activity is mainly located in brain areas related to executive functions, visual perception, memory, and language processing, suggesting that CRC patients may be at risk of cognitive deterioration. Overall, these findings afford valuable insights into understanding the neuropathophysiological mechanism of cognitive deterioration in CRC patients.

CRC, colorectal cancer; rs-fMRI, resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging; HCs, healthy controls; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; ALFF, amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations; ReHo, regional homogeneity; DC, degree centrality; 3D-T1WI, three-dimensional high-resolution T1-weighted imaging; TR, repetition time; TE, echo time; FOV, field of view; FA, flip angle; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; SPSS, Statistical Product and Service Solutions; MATLAB, Matrix Laboratory; DPABI, Data Processing Analysis of Brain Imaging; SPM, Statistical Parametric Mapping; FD, frame-wise displacement; XELOX, capecitabine + oxaliplatin; FOLFOX, oxaliplatin + calcium folinate + fluorouracil; M, male; F, female; MNI, Montreal Neurological Institute; AAL, automated anatomical labeling; MOG_L, left middle occipital gyrus; MTG_L, left middle temporal gyrus; PoCG_L, left postcentral gyrus; PoCG_R, right postcentral gyrus; LING_R, right lingual gyrus; ANG_R, right angular gyrus; PCUN_R, right precuneus.

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available since some data may be identifiable but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

YX, ZM, JC, HZ, GS: (1) designed the protocol for this study; (2) obtained, analyzed and interpreting the data for this study; (3) drafted and wrote the manuscript. GH, WZ, LZ: (1) designed the protocol for this study; (2) obtained, analyzed and interpreting the data for this study; (3) obtained research funding; (4) administrative, technical, and material support; (5) proposed revisions to this research idea; (6) revised and annotated the content of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

This study followed the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Gansu Provincial Hospital (approval numbers: 2015–154, 2023–004). The participants signed a written informed consent form.

We thank all the participants and investigators except the authors in this study.

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Gansu Province (No. 23JRRA1772).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.