1 Department of Neurology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Jinzhou Medical University, 121001 Jinzhou, Liaoning, China

2 Institute of Cerebrovascular Disease Research, Xuanwu Hospital of Capital Medical University, 100053 Beijing, China

3 Department of Neurology, Xuanwu Hospital of Capital Medical University, 100053 Beijing, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Background: Clinically, ischemic reperfusion injury is the main cause

of stroke injury. This study aimed to assess the effectiveness of fingolimod in

suppressing inflammation caused by ischemic brain injury and explore its

pharmacological mechanisms. Methods: In total, 75 male Sprague-Dawley

rats were randomly and equally assigned to five distinct

groups: sham, middle cerebral artery occlusion/reperfusion (MCAO/R) surgery,

fingolimod low-dose (F-L), fingolimod medium-dose (F-M), and fingolimod high-dose

(F-H). Neurobehavioral tests, 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride staining, and

the brain tissue drying-wet method were conducted to evaluate neurological

impairment, cerebral infarction size, and brain water content. Enzyme-linked

immunosorbent assay was employed to quantify pro-inflammatory cytokines

interleukin (IL)-1

Keywords

- fingolimod

- inflammation

- ischemic injury

- HMGB1

- TLR4

- NF-κB

As the most prevalent type of cerebrovascular disease, ischemic stroke imposes an apparent financial burden on affected patients, their families, and even the entire society [1]. It occurs owing to narrowing or complete blockage of the cerebral blood vessels, resulting in irreversible neuronal cell death and neurological impairment [2, 3].

Cerebral ischemic injury triggers a strong inflammatory response, which is a

critical characteristic of ischemic stroke pathology that occurs within hours of

blood vessel blockage. This inflammatory response significantly increases the

levels of inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin (IL)-6 and tumor necrosis

factor-alpha (TNF-

Immediate restoration of cerebral blood flow to salvage the infarcted cerebral hemisphere is the most efficient therapeutic approach for ischemic stroke. Currently, intravenous thrombolysis using a recombinant tissue plasminogen activator is a relatively safe and widely accepted treatment for ischemic stroke. However, this method can result in cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury, as well as a cascade of intricate processes, which encompass inflammation, oxidative stress, apoptosis, and autophagy [5]. Therefore, it is crucial to explore and develop novel and reliable strategies and medications that not only restore cerebral blood flow but also alleviate ischemic brain injury.

Fingolimod, also known as FTY720, is synthesized through the chemical modification of myriocin, an extract of Cordyceps sinensis [6]. Additionally, fingolimod, an immunosuppressive medication that has been given the green light by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for its use in treating multiple sclerosis, is essential for maintaining vascular integrity, lymphocyte transport, and immune response modulation [6, 7]. A clinical study found that patients with acute ischemic stroke who received short-term fingolimod therapy alongside standard stroke therapy exhibited a decrease in microvascular permeability, secondary injury, and better clinical outcomes [8]. However, the underlying pharmacological mechanisms of action of fingolimod in ischemic brain injury remain to be fully understood.

This study aimed to investigate the effects and mechanisms of action of various doses of fingolimod on ischemic brain injury. First, we assessed the neuroprotective efficacy of various doses of fingolimod in ischemic brain injury. Subsequently, we explored the physiological role of various doses of fingolimod in protecting against inflammation after experiencing cerebral ischemia. Additionally, we investigated the underlying pharmacological mechanisms of fingolimod in inflammation induced by ischemic brain injury, utilizing a rat model that simulates transient focal cerebral ischemia.

The animal experiments adhered to the protocols outlined in the National Institutes of Health’s “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” and received approval from the Animal Care and Use Committee at Jinzhou Medical University (2022022701). A total of 75 clean, healthy male Sprague Dawley (SD) rats weighing between 250 and 280 grams and aged 8 to 9 weeks, were supplied by the Experimental Animal Center at Jinzhou Medical University (Jinzhou, China). On day 3 after adaptive feeding, rats were randomly allocated into different groups (n = 15): (1) sham group, (2) middle cerebral artery occlusion/reperfusion (MCAO/R) surgery group, (3) fingolimod low-dose (F-L) group (0.5 mg/kg), (4) fingolimod medium-dose (F-M) group (1.0 mg/kg), (5) fingolimod high-dose (F-H) group (2.0 mg/kg).

Fingolimod (Cat #HY-11063, MedChemExpress, Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA) was prepared in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO, D8371, Beijing Solebao Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) and diluted in a 0.9% NaCl saline solution to final concentrations (0.5, 1.0, and 2.0 mg/kg). On days 0 (immediately after MCAO) and 1 (24 h) after MCAO, rats in the MCAO/R group were intraperitoneally administered normal saline containing DMSO, whereas rats in the F-L, F-M, and F-H groups were intraperitoneally administered the same volume of fingolimod at different concentrations (0.5, 1.0, and 2.0 mg/kg).

MCAO procedure was executed using an adapted

thread embolism method, as outlined in prior research [9]. The rats were

anesthetized by placing them in a chamber containing a mixture of 4.0–5.0%

isoflurane (Cat# R510, RWD Life Science, Shenzhen, Guangdong, China) and oxygen

and then maintained during MCAO surgery with 1.5–2.0% isoflurane in a mixture

of 70% N

A median incision approximately 4 cm in length was made in the middle of the

neck. The subcutaneous fat and surrounding connective tissue were carefully

stripped to expose the carotid sheath and dissected to expose the common carotid

artery (CCA), internal carotid artery (ICA), and external carotid artery (ECA).

The superior thyroid and the occipital arteries were isolated and

electrocoagulated. The CCA and ICA were temporarily clamped, and the ECA was

ligated with a nylon monofilament at the distal end. A V-shaped incision was made

at the distal end of the ECA at a 45

The filament was removed 2 h after MCAO to restore cerebral blood flow.

Hemostasis was checked, and the wound was closed using nylon sutures. For rats in

the sham group, the CCA was isolated without ligation or hypoxia. The rats’

rectal temperature was maintained at approximately 37.0

The Zea-Longa score was used to evaluate neurological recovery following the method described in a previous study [10]. The scoring system ranges from 0 to 4, with the following interpretations: 0 = no apparent neurological deficits, 1 = incomplete extension of the left forelimb, 2 = a leftward circling motion, 3 = left-sided weakness, and 4 = the absence of spontaneous walking and a lack of consciousness.

The rats were humanely sacrificed 2 h after the second

administration of the drug by administering excessive anesthesia

(amobarbital; Cat #17784, Cayman Chemical Company, Ann Arbor, MA, USA,

10%, 0.5 mL/100 g). After cardiac perfusion, rat brains were excised through

decapitation and then cut into 2 mm thick coronal sections. These slices were

then placed in a 2%

2,3,5-Triphenyltetrazolium Chloride (TTC, T8877, Sigma, Burlington, MA,

USA) solution and incubated at 37 °C for 10 min. Subsequently, slices

were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. The infarct volume was assessed using

ImageJ software (version 1.5, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA). To calculate the

percentage of the ischemic lesion area, we used the following equation: infarct

volume (%) = (volume of contralateral hemisphere – volume of non-infarcted

ipsilateral hemisphere)/volume of contralateral hemisphere

The rats were euthanized 2 h after the second administration of the drug under

excessive anesthesia (amobarbital; Cat# 17784, Cayman Chemical Company, Ann Arbor, MA, USA, 10%, 0.5 mL/100 g). Subsequently, cerebral tissue was derived from rats without

myocardial perfusion. The humidity of the cerebral tissue was assessed

immediately after the rats were sacrificed. The cerebral tissue was

microwave-dried in a microwave oven at 100 °C until the cerebral weight remained

constant, known as dry weight. Brain water content was assessed using the

following formula: brain water content (%) = [(humid brain weight – dry brain

weight)/humid brain weight]

Pro-inflammatory factors TNF-

Immunohistochemical staining was carefully conducted throughout the entire

process according to a previously mentioned protocol [11]. Rat cerebral tissues

were completely immersed in formalin, fixed, dehydrated, and embedded in paraffin

wax. The paraffin-embedded cerebral tissue blocks mentioned above were then cut

into 5 µm thick slices. The tissue slices were placed in fixation boxes

containing citrate antigen retrieval buffer and fixed in a microwave oven. Once

the slices had reached room temperature, they were immersed in a solution

containing 3% hydrogen peroxide to block the activity of endogenous peroxidase

and then immersed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) wash buffer three times. The

slices were then incubated at 4 °C in the refrigerator with various primary

antibodies: rabbit anti-high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) antibody (1:500; Cat# ET1601-2, HuaAn

Biotechnology, Hangzhou, Zhengjiang, China), rabbit toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) antibody (1:400; Cat#

ab22048, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), and rabbit anti-nuclear factor kappa-B p65 (NF-

The infarcted rat hippocampus was lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA)

buffer (Cat #P0013B, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) containing a mixture of protease

and phosphatase inhibitors. The mixture containing the lysate

and tissue was subjected to centrifugation at a speed of 12,000

rpm for a duration of 30 min, and the supernatant was carefully poured into a new

tube. The supernatant was gently mixed with sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide

gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) loading buffer and then heated at 95 °C for 5 min

in a water bath. About 20 µg of protein was segregated and subsequently

moved onto a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA,

USA) with a pore size of either 0.22 micrometers or 0.45 micrometers. To block

nonspecific protein binding, the PVDF membrane was soaked in a solution

containing 5% skim milk. After blocking, the membrane was then immersed in the

following primary antibodies overnight at a controlled temperature of 4 °C within

a refrigerated environment: anti-HMGB1 (1:1000; Cat# ET1601-2, HuaAn

Biotecchnology, Hangzhou, Zhengjiang, China), anti-TLR4 (1:500, Cat# WL00196, WanLei

Biotechnology, Shenyang, Liaoning, China), anti-NF-

Experimental data are presented as mean

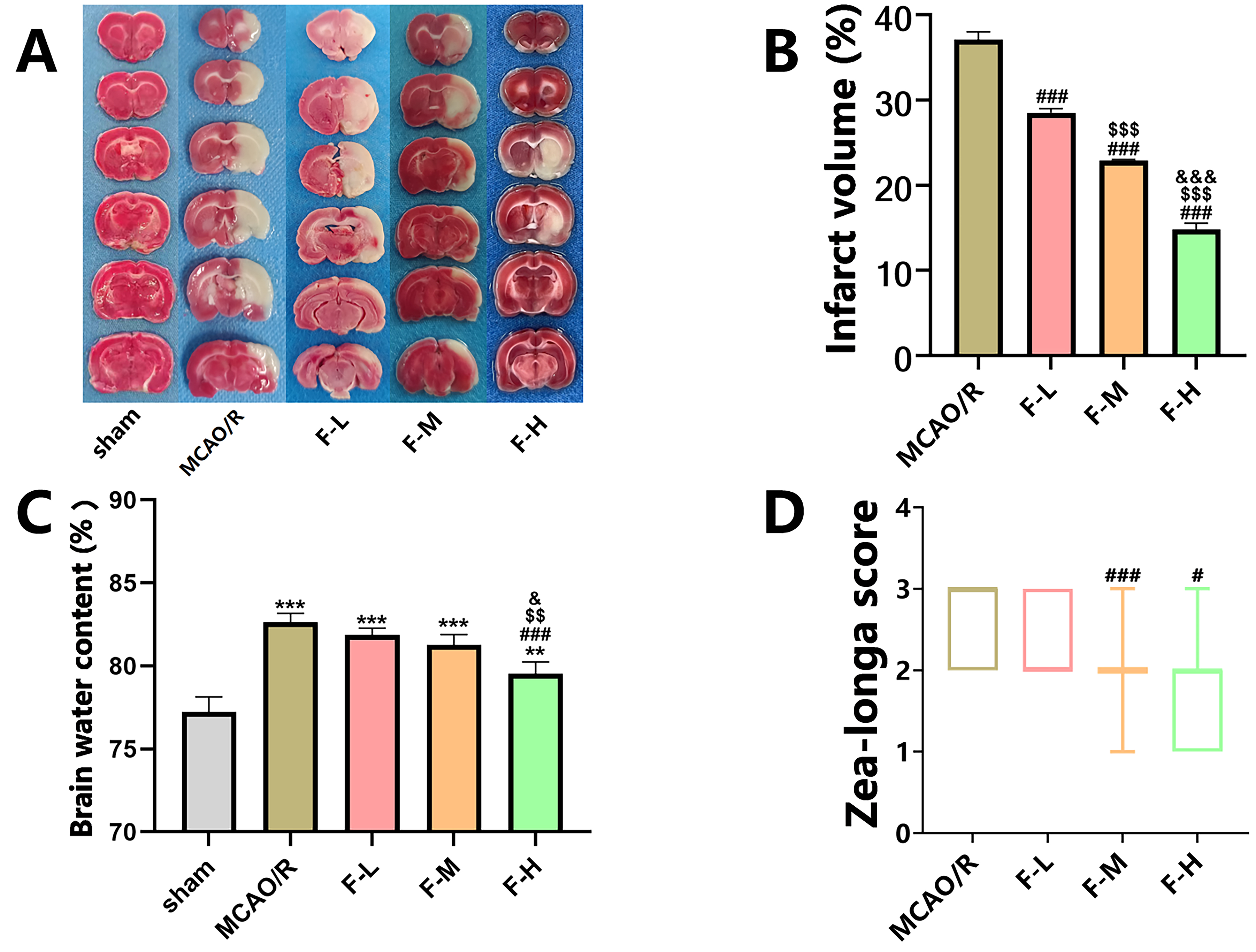

TTC staining revealed no apparent damage to cerebral tissue in the sham group

(Fig. 1A). On the contrary, rats in the MCAO/R group exhibited significant brain

tissue lesions 1 d after cerebral ischemia or reperfusion injury (Fig. 1A).

However, treatment with various fingolimod doses significantly reduced the volume

of the cerebral infarct area in rats subjected to MCAO/R (Fig. 1A,B; p

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Fingolimod effectively reduces cerebral infarction

volume, alleviates cerebral edema, and improves neurological function in MCAO/R

rats. (A) On the first day post-MCAO/R procedure, TTC staining images were

captured, wherein the infarcted regions of the brain were depicted in white and

the healthy regions in red. (B) Quantification of TTC staining (Data presented as

mean

To assess the effectiveness of fingolimod therapy in treating cerebral edema,

the brain water content was determined one day post-reperfusion. The findings

indicated that the rats subjected to MCAO/R had elevated water content in their

cerebral tissues when compared to the rats in the sham group (Fig. 1C, p

Additionally, to examine the effects of different dosages of fingolimod on the

restoration of neurological function, we used the Zea-Longa Scale neurological

score for each group. The results demonstrated that high-dose fingolimod

administration (2.0 mg/kg) resulted in a statistically

significant reduction in the neural function score compared to that in the MCAO/R

group (Fig. 1D, p

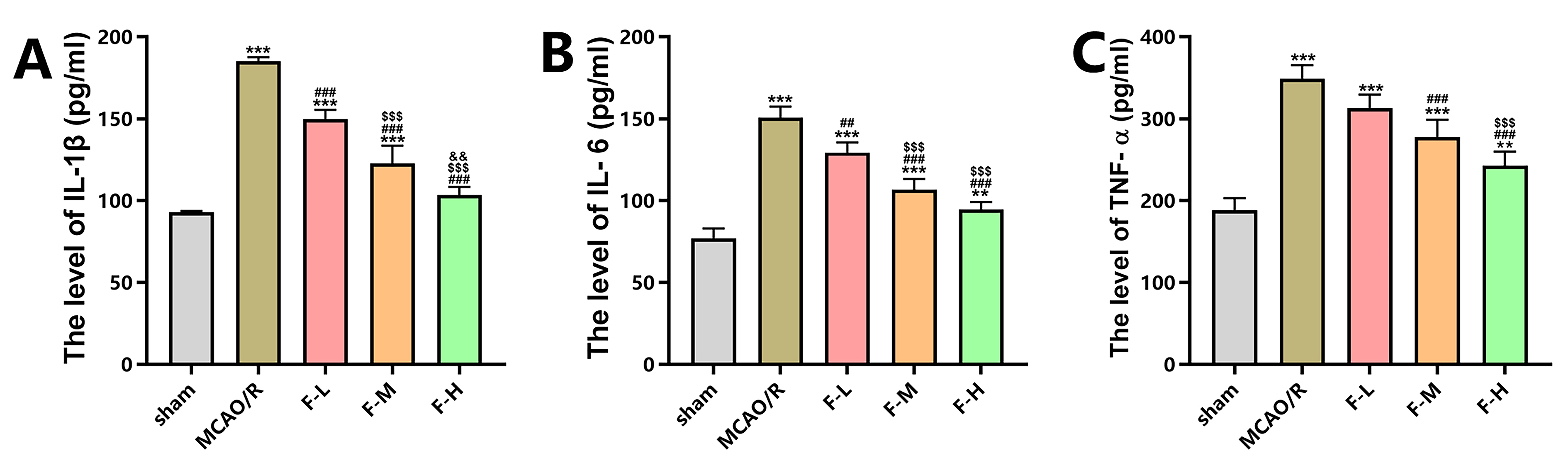

The levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in serum, including TNF-

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Fingolimod inhibits inflammation in rats after MCAO/R. (A)

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) was employed to measure the serum

concentrations of interleukin-1 beta (IL-1

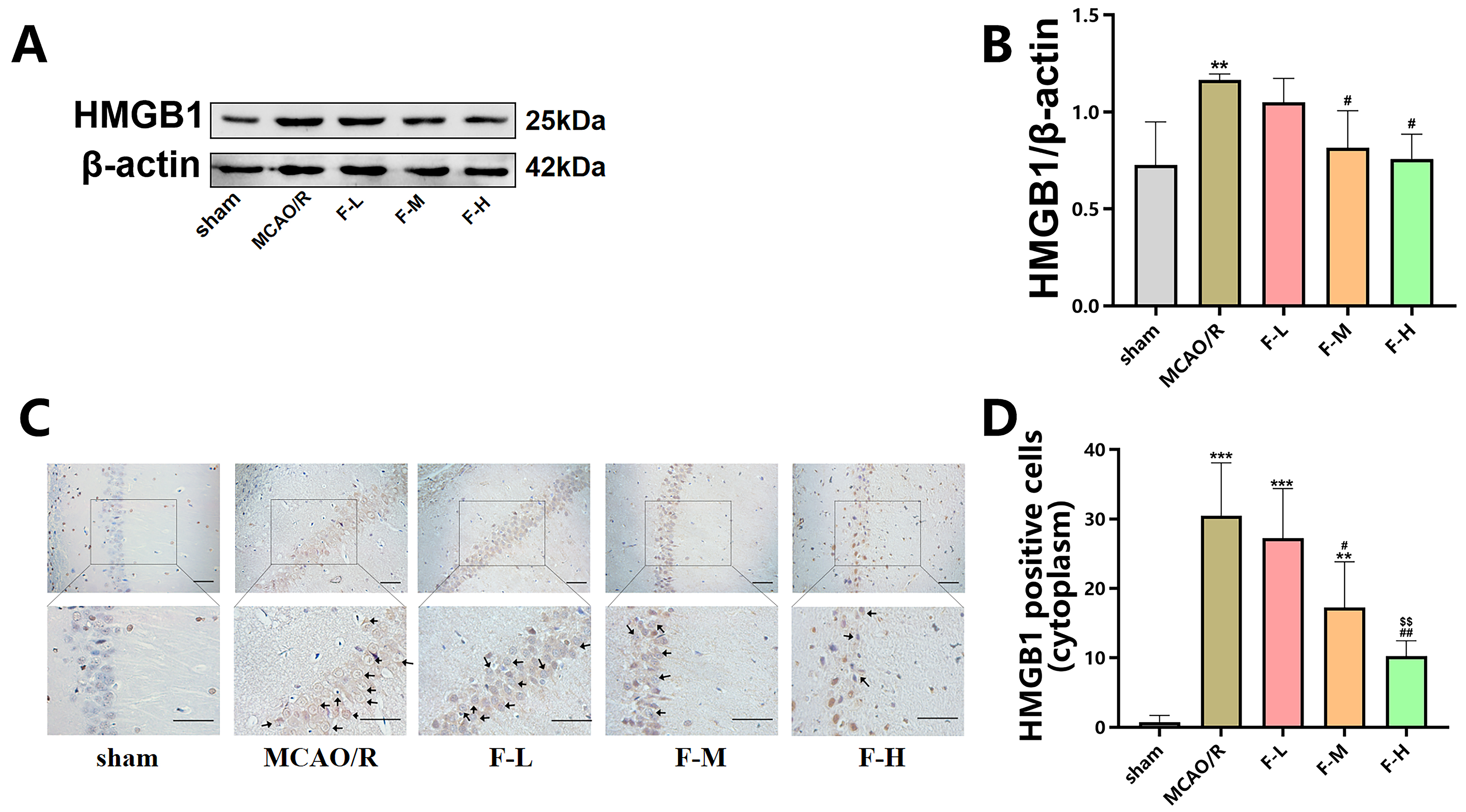

The expression levels of HMGB1 following MCAO/R injury in rats

were measured via western blot assays and immunohistochemical staining. Western

blot analysis demonstrated an apparent increase in the levels

of HMGB1 protein in the MCAO/R group when compared to the sham group (Fig. 3A,B;

p

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Fingolimod down-regulates the expression of

HMGB1 in MCAO/R rats. (A) The expression levels of HMGB1

within the hippocampal region of these rats were measured using the technique of

western blot analysis, with the assessment being conducted day 1 post the MCAO/R

procedure. (B) Quantification analysis of HMGB1 by western blot (Data presented

as mean

Additionally, we performed immunohistochemical analysis of HMGB1 in hippocampal

slices from rats in the different groups. Immunohistochemistry revealed

HMGB1-positive protein deposition in both the cell nucleus and cytoplasm.

The number of cytoplasm-positive HMGB1

staining cells was significantly higher in the MCAO/R group than in the sham

group (Fig. 3C,D; p

These results suggest that fingolimod treatment downregulated HMGB1 protein expression in MCAO/R rats. Additionally, fingolimod treatment inhibited the translocation of HMGB1 from the cell nucleus to cytoplasm to induced by cerebral ischemic injury.

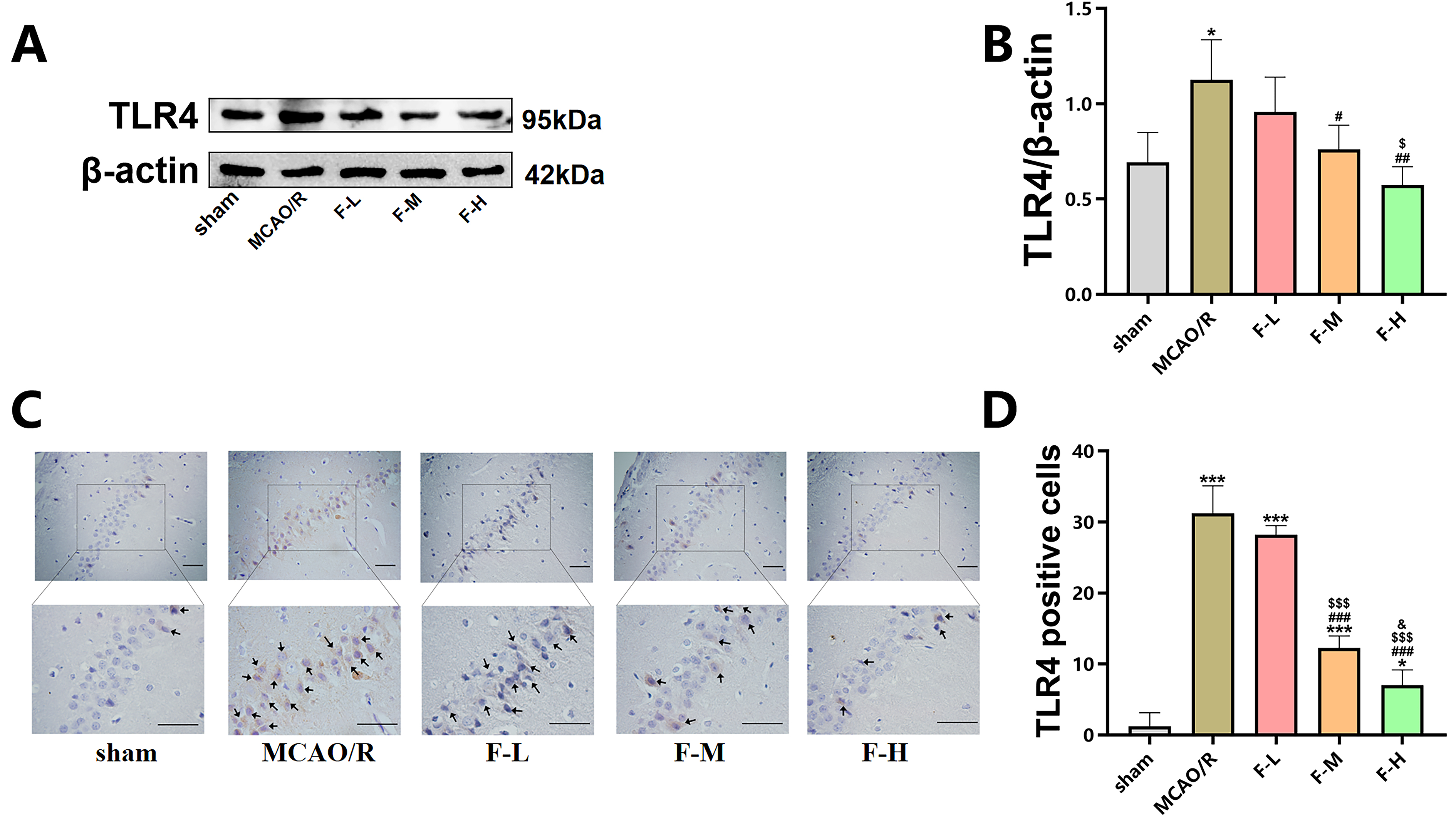

The effect of various doses of fingolimod on TLR4 expression following MCAO/R injury in rats was evaluated using western blot assays and immunohistochemical staining.

Western blot analysis demonstrated that ischemic brain injury

increased the expression level of TLR4 (Fig. 4A,B; p

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Fingolimod inhibits TLR4 expression in MCAO/R

rats. (A) The expression of TLR4 in the hippocampus of rats

was detected using western blot analysis on day 1 after MCAO/R. (B)

Quantification of TLR4 expression via western blot analysis (Data presented as

mean

In summary, these results demonstrate that fingolimod treatment can effectively suppress the expression levels of TLR4 in rats that have undergone MCAO/R.

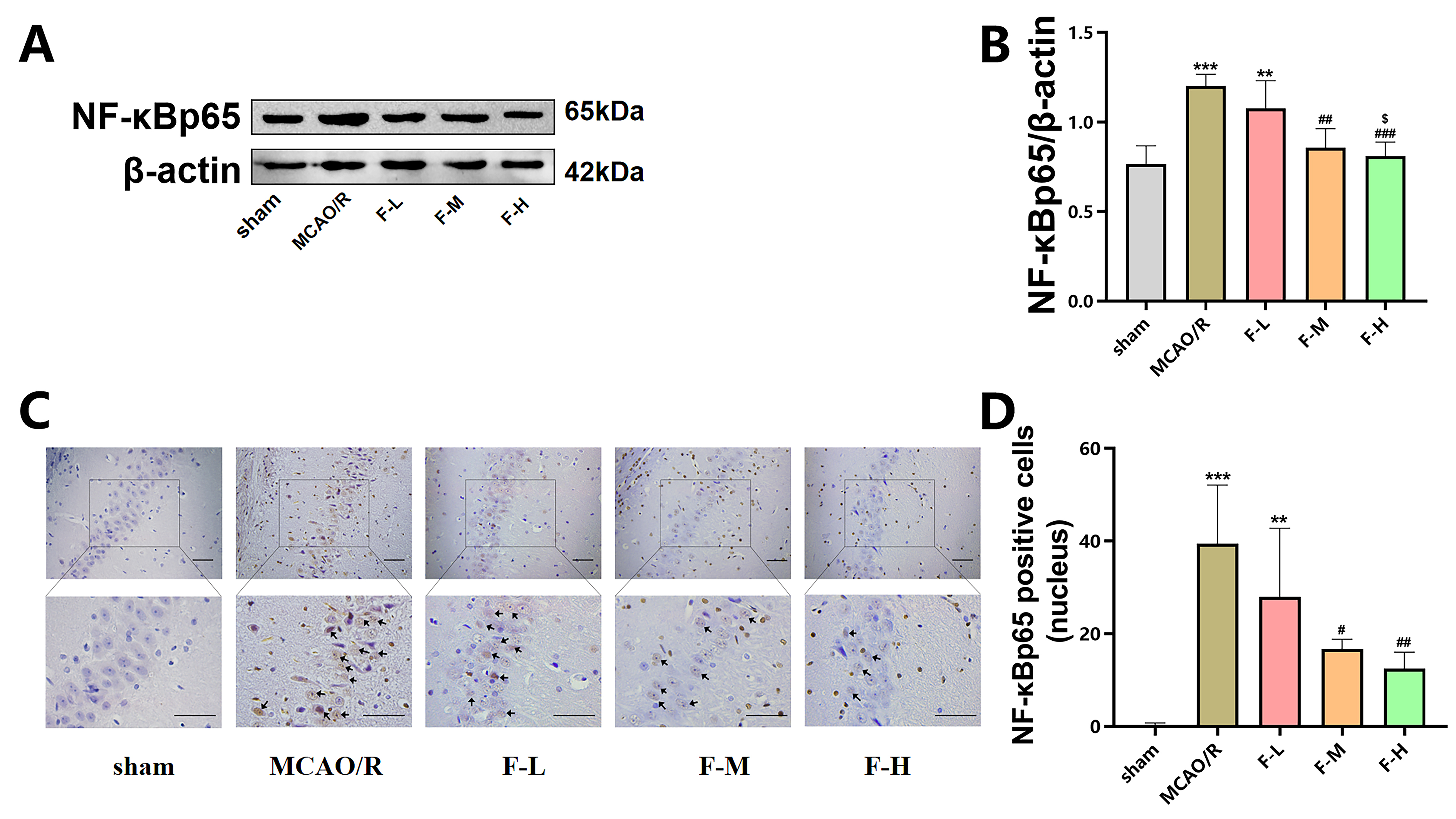

To assess the impact of fingolimod treatment

on NF-

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Fingolimod treatment reduces NF-

These findings provide compelling evidence that fingolimod treatment reduces the

NF-

Ischemic stroke, which is primarily caused by ischemia or reperfusion brain injury, is a significant contributor to deaths globally [12]. Although early restoration of cerebral blood flow is crucial for reducing brain tissue injury, reperfusion can also cause secondary brain damage, including blood-brain barrier (BBB) damage and inflammation [13]. Consequently, mitigating the harmful impacts of cerebral ischemia and reperfusion has consistently been a central focus within extensive research efforts. Natural products have emerged as a significant source for drug development because of their minimal side effects and potent multi-target activity [14]. Fingolimod, a compound derived from Cordyceps sinensis, mitigates cerebral ischemic-reperfusion injury [15]. It easily traverses the BBB and accumulates in the brains of both humans and animals [16]. Additionally, fingolimod treatment enhances neurogenesis and facilitates repair in central nervous system injury models by activating endogenous neural precursor cells (NPCs) or oligodendrocyte progenitors [17]. The objective of this research was to assess and compare the therapeutic efficacy of various doses of fingolimod in rats subjected to MCAO/R and explore the potential pharmacological mechanisms and molecular basis that underlie the drug’s effects.

Our findings indicate that fingolimod treatment effectively mitigates brain edema, promotes recovery of neurobehavioral function, and provides neuroprotection following cerebral ischemia or reperfusion. Moreover, we observed a dose-dependent reduction in cerebral infarction volume following fingolimod treatment. Collectively, these results demonstrate that fingolimod possesses neuroprotective properties in a rat model characterized by transient focal cerebral ischemia.

Dysregulated inflammation significantly affects cerebrovascular diseases,

particularly ischemic stroke [18]. Inflammatory mediators, including cytokines

IL-1

Another important protein involved in early inflammatory responses is HMGB1.

Research has shown that during cell injury, HMGB1, a highly conserved

multifunctional protein, is moved from the nucleus to the cytoplasm and then

actively secreted by immune cells like monocytes and macrophages, or released

from necrotic cells [25, 26]. It plays a crucial role in stimulating the

production of TNF-

Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), a downstream receptor of HMGB1, has a significant

effect on inflammatory responses [31]. HMGB1 triggers inflammatory signals by

binding to its receptor for TLRs or advanced glycation end products, thereby

activating a pro-inflammatory response [32]. A clinical trial has demonstrated

that up-regulation of TLR4 expression is closely related to elevated serum levels

of several inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1

Nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-

Our study provides evidence of the neuroprotective

capabilities of fingolimod in ischemic stroke and sheds light on the underlying

pharmacological mechanism of inflammation following ischemic stroke. We

demonstrated that fingolimod treatment effectively reduced the volume of brain

tissue infarction, alleviated brain edema, and promoted a dose-dependent recovery

of neurological function in rats that underwent MCAO/R. Additionally, we observed

that fingolimod exerted its anti-inflammatory effects by suppressing the

HMGB1/TLR4/NF-

The data will be available on reasonable request.

LM, YL contributed to the conception and design of the study; YX, LZ, JG and CB contributed to the acquisition and analysis of data; YX and LZ contributed to drafting the text and preparing the figures. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The animal procedures performed followed the guidelines of National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Jinzhou Medical University (2022022701).

Not applicable.

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81774116).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/j.jin2308142.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.