1. Introduction

Stroke is a prevalent cerebrovascular disorder characterized by significant

rates of disability and mortality. The two primary classifications of stroke

are hemorrhagic stroke and ischemic stroke. Ischemic strokes

account for approximately 80% of all stroke cases, with middle cerebral artery

thromboembolism as the principal etiology [1]. Patients who experience ischemic

stroke frequently exhibit significant neurological impairments. At present, the

sole interventions that have demonstrated efficacy during the acute phase of

ischemic stroke are the administration of tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) and

mechanical thrombectomy [2]. Unfortunately, the therapeutic

window is narrow, and only a small proportion of patients are

eligible [3, 4, 5]. Therefore, potential drugs for ischemic stroke

treatment are urgently needed. The pathophysiology of ischemic

stroke involves complicated molecular mechanisms, such as

oxidative stress, inflammation and apoptosis. Available

pharmacological therapies targeting crucial stages in the pathophysiology of

ischemic stroke aim to promote optimal poststroke neurological recovery by

reducing neuronal apoptosis, inhibiting inflammation, promoting angiogenesis, and

removing free radicals [6, 7]. However, the performance of these therapies is not

clinically satisfactory. In recent years, promoting

neurogenesis from endogenous neural stem cells (NSCs)

has emerged as a promising therapeutic approach for treating

ischemic stroke [8].

Josef Altman was the first to present evidence of neurogenesis in the adult

brain when he identified newly formed neurons and glial cells through the use of

tritiated thymidine to label proliferating cells [9]. Since then, accumulating

evidence has revealed that neurogenesis persists in the adult

mammalian brain. Although research on adult neurogenesis in

humans is controversial, the occurrence of neurogenesis in the adult human brain

is widely acknowledged [10, 11]. Presently, two extensively

documented neurogenic niches housing adult NSCs exist within the adult brain: the

subventricular zone (SVZ) located in the lateral ventricle (LV)

and the subgranular zone (SGZ) situated in the dentate gyrus (DG) of the

hippocampus. Under normal physiological conditions, SVZ NSCs

are responsible for the production of transit-amplifying cells

(TACs), subsequently leading to the emergence of neuroblasts. These neuroblasts

undergo migration along the rostral migratory stream (RMS) to reach the olfactory

bulb (OB), where they differentiate into interneurons that play a crucial role in

the sense of smell. NSCs located in the SGZ are responsible for generating

excitatory glutamatergic neurons, which subsequently integrate into the granule

cell layer of the DG. These neurons play a crucial role in

spatial and temporal memory processing. During ischemic stroke,

SGZ NSCs proliferate and migrate toward the granule cell layer within the DG,

although their migration remains confined within the boundaries of the

hippocampus [12]. Simultaneously, ischemic

injury drastically increases neurogenesis in both rodent and human SVZs, and

neuroblasts deviate from the conventional pathway toward the

adjacent parenchyma and striatal ischemic penumbra. Within the

ischemic penumbra, a limited population of neuroblasts produces neurons,

potentially facilitating tissue restoration and the recovery of

locomotor function. However, a significant proportion of NSCs undergo

differentiation into astrocytes, which subsequently transform into reactive

astrocytes that play a crucial role in the process of glial scar formation. This

impedes the effective repair of nerve injuries [8, 13, 14]. A

prior investigation employed a genetic approach utilizing the herpes simplex

virus thymidine kinase/ganciclovir (HSV-TK/GCV) suicide system to eliminate

doublecortin (DCX) neuroblasts, which led to increased

infarct size and exacerbated neurological impairments in mice that underwent

middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) [15]. These findings indicate that

neurogenesis induced by ischemia appears to play a role in alleviating

histological and neurobehavioral impairments.

Taken together, these findings indicate that enhancing neurogenesis and

augmenting neuronal regeneration within the ischemic penumbra subsequent to

cerebral ischemia can potentially enhance the restoration of neurological

function. Multiple pathways are believed to be implicated in adult neurogenesis,

including the Notch signaling pathway [16], Sonic Hedgehog signaling (SHH)

pathway [17, 18], and bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling pathway [19, 20]. This review primarily concentrates on the role of the

Wnt/-catenin pathway in adult neurogenesis and its potential therapeutic

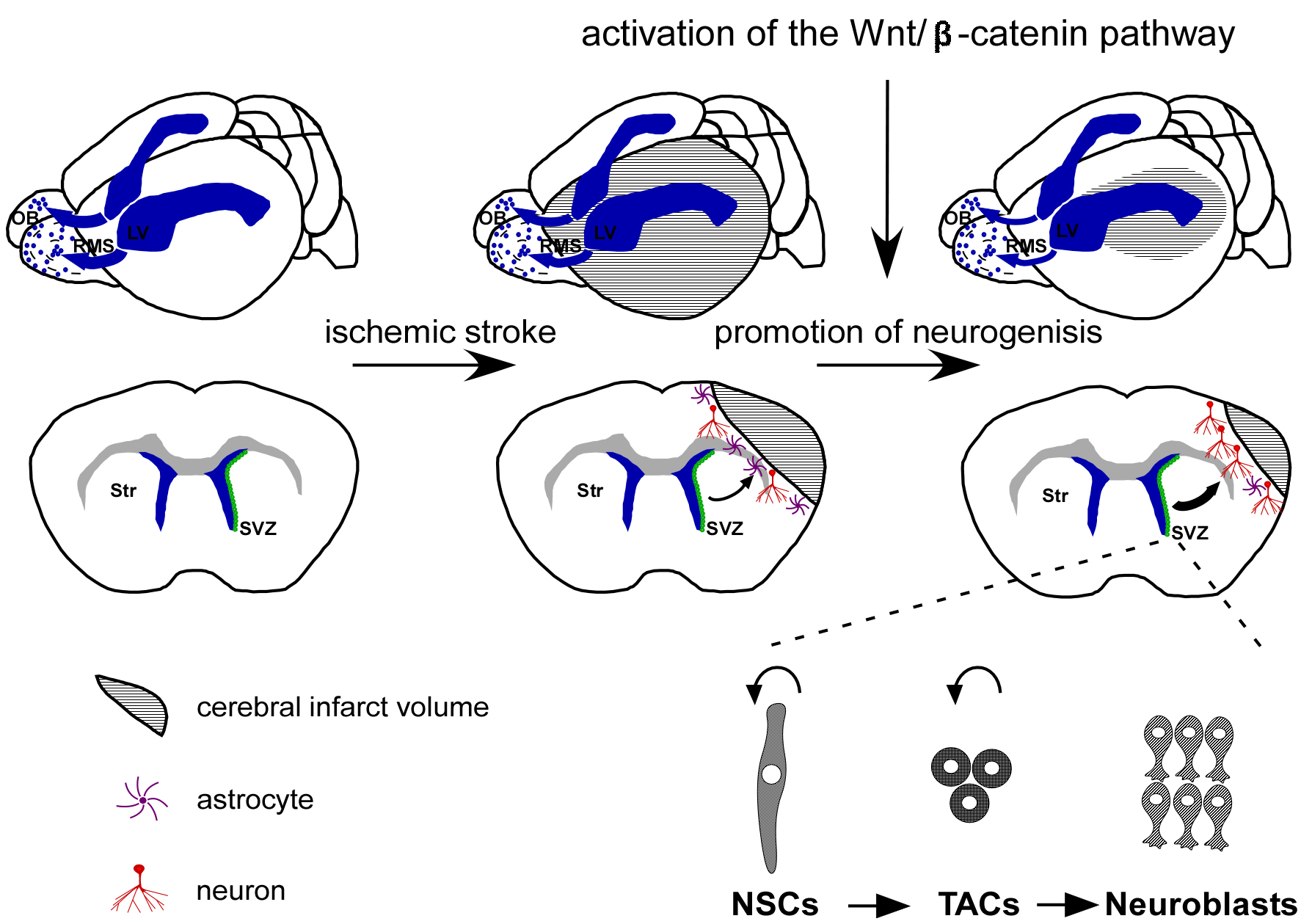

implications for the management of cerebral ischemia (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Activation of the Wnt/-catenin pathway offers a

promising therapeutic strategy for treating ischemic stroke by promoting

neurogenesis. Under typical physiological circumstances, SVZ NSCs are

responsible for producing TACs, which possess the capacity to generate

neuroblasts that subsequently migrate through the RMS toward the OB, where they

undergo differentiation into interneurons. However, in the event of ischemic

stroke, neuroblasts deviate from their conventional pathway toward the ischemic

penumbra. Within the ischemic penumbra, a limited population of neuroblasts

produces neurons. Activation of the Wnt/-catenin pathway has been shown

to facilitate neurogenesis and augment neuronal regeneration within the ischemic

penumbra following cerebral ischemia, leading to an improvement in nerve function

impairment. SVZ, subventricular zone; NSCs, neural stem cells; TACs,

transit-amplifying cells; RMS, rostral migratory stream; OB, olfactory bulb; LV, lateral ventricle; Str, Striatum.

2. The Wnt Signaling Pathway

The Wnt signaling pathway primarily consists of Wnt ligands, which are secreted

glycoproteins, and cell-surface receptors called Frizzled. The

mammalian genome harbors a total of 19 Wnt genes that

encode Wnt ligands. Wnt signaling pathways can be categorized into three

different types: the Wnt/-catenin pathway (also referred to as the

canonical Wnt signaling pathway), the planar cell polarity pathway (Wnt/PCP), and

the Wnt/Ca signaling pathway.

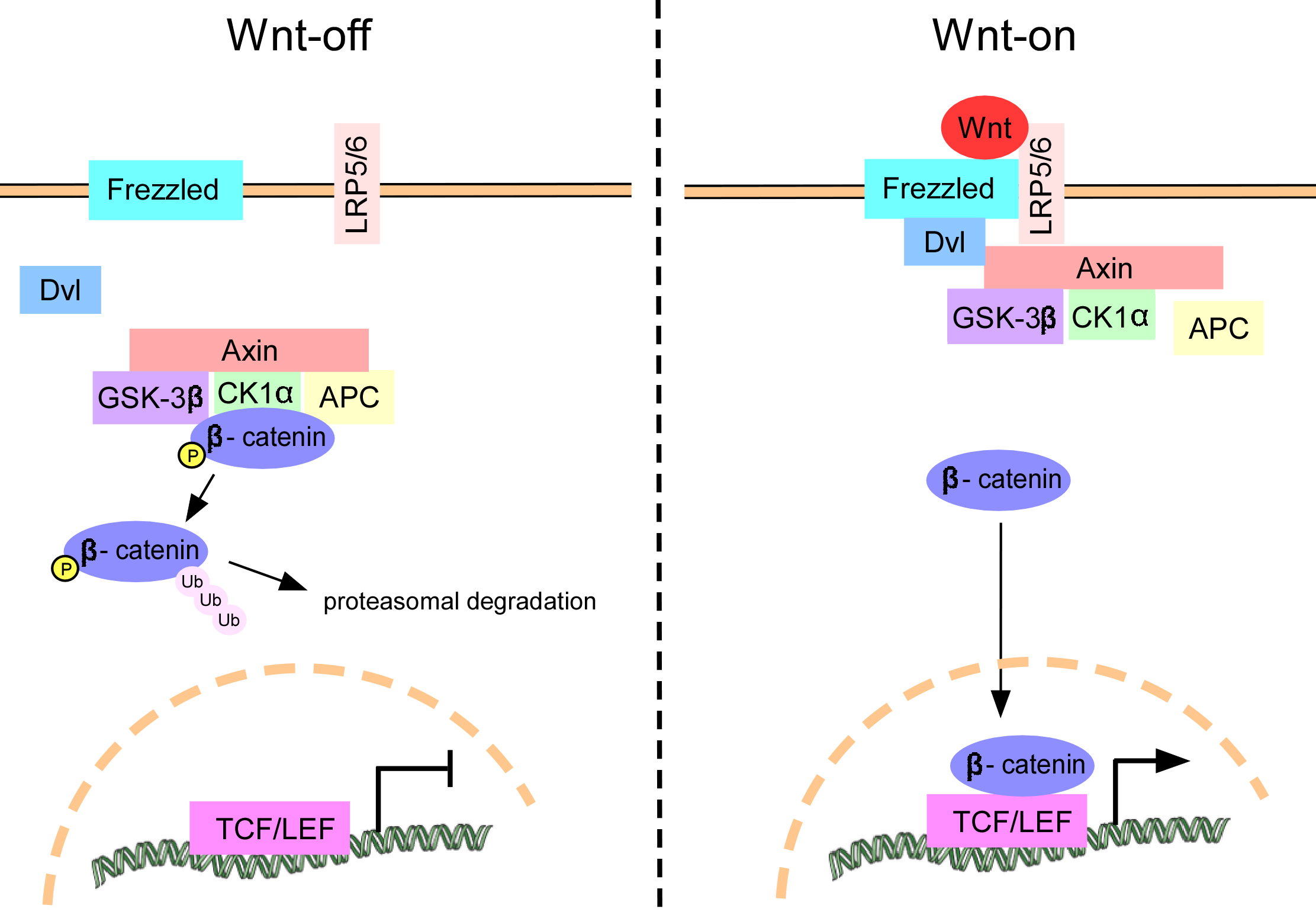

In the canonical Wnt signaling pathway, Wnt ligands bind to

the Frizzled receptor (Fzd) and low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein

5/6 (LRP5/6). Then, the cytoplasmic protein Dishevelled (Dvl) is activated.

Activation of Dvl leads to the degradation of a complex containing glycogen

synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3), adenomatous polyposis coli (APC),

the protein kinase casein kinase 1 (CK1), and Axin. In the

absence of Wnt pathway activation, the

GSK-3/APC/CK1/Axin complex phosphorylates cytosolic

-catenin, leading to its ubiquitination and subsequent degradation by

the proteasome. Conversely, upon activation of the Wnt pathway, the degradation

machinery of the GSK-3/APC/CK1/Axin complex is hindered,

resulting in the cytosolic accumulation of -catenin and its subsequent

transportation into the nucleus. Intranuclear -catenin participates in

interactions with T-cell factor/lymphoid enhancer-binding factor (TCF/LEF)

proteins, thereby promoting the transcription of downstream genes (Fig. 2)

[21, 22, 23]. In addition to the canonical pathway, Wnt ligands can

initiate various signaling cascades that do not rely on -catenin,

namely, the Wnt/PCP pathway and the Wnt/Ca signaling pathway. The Wnt/PCP

pathway begins with the interaction between a Wnt ligand and Fzd, subsequently

leading to the activation of Dvl. The activation of Dvl, in turn, initiates the

activation of small G proteins, including Rac and Rho, which subsequently

activate Rho-associated kinase (ROCK) and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK). This intricate series of events ultimately contributes to

the establishment of cellular polarity and the facilitation of cell migration

[24, 25]. The initiation of the Wnt/Ca pathway occurs

when a Wnt ligand interacts with Fzd, leading to the subsequent activation of

phospholipase C (PLC). This activation subsequently modulates the release of

calcium from the endoplasmic reticulum, thereby governing the regulation of

intracellular calcium concentrations [26].

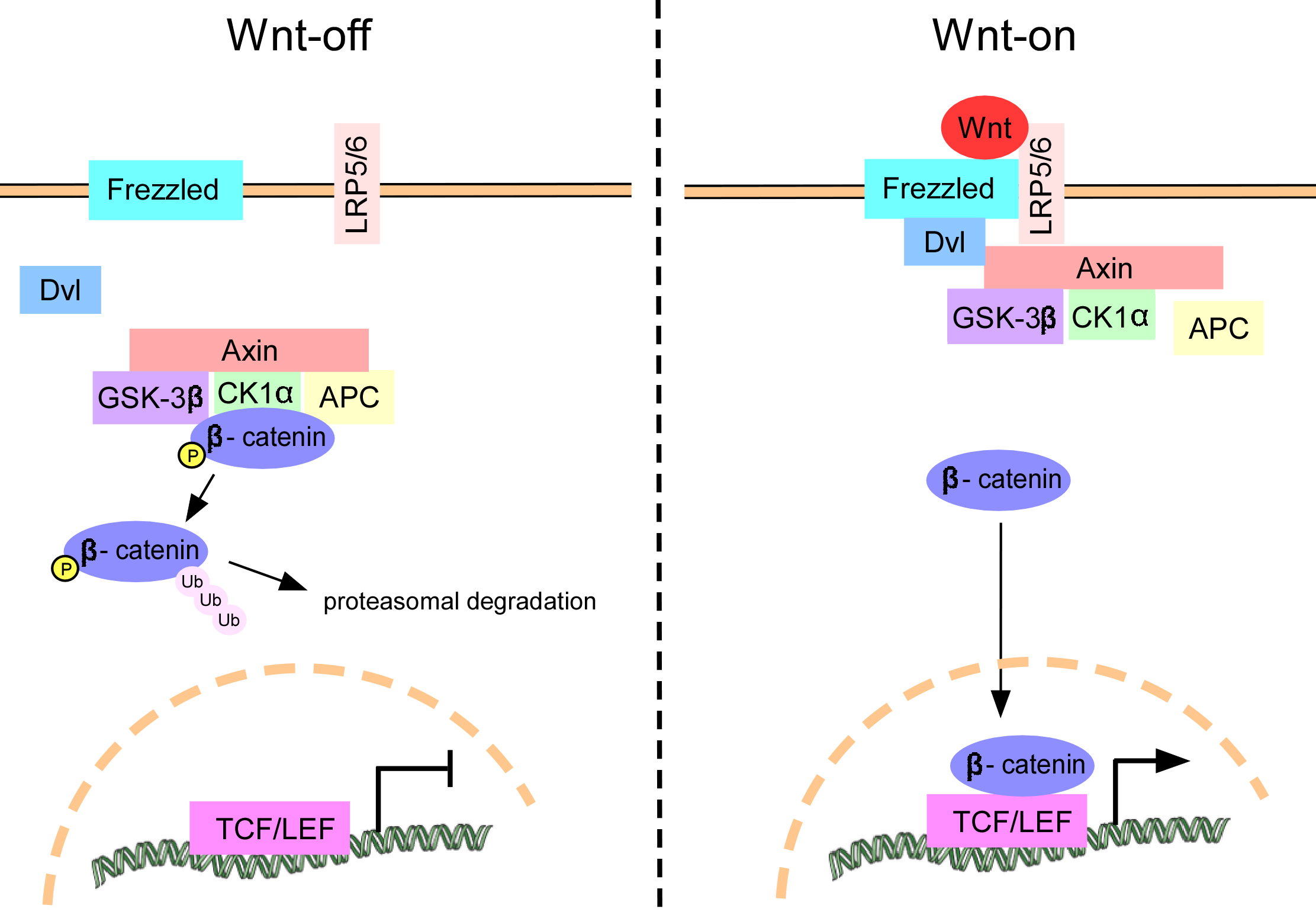

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Schematic diagram of the Wnt/-catenin

pathway. In the absence of Wnt ligand stimulation,

-catenin undergoes phosphorylation by the

GSK-3/APC/CK1/Axin complex, leading to its ubiquitination and

subsequent removal via the proteasome (Wnt-off). Upon

activation of the Wnt/-catenin pathway, the Wnt ligand

binds to the Frizzled receptor and LRP5/6, resulting in

activation of the cytoplasmic protein Dvl. This activation of Dvl triggers the

degradation of the GSK-3/APC/CK1/Axin complex, leading to the

accumulation of -catenin in the cytosol and its subsequent translocation

into the nucleus. In the nuclear compartment, -catenin engages in

interactions with TCF/LEF proteins, thereby facilitating the transcription of

genes located downstream (Wnt-on). Dvl, Dishevelled; GSK-3β, glycogen synthase kinase-3β; APC, adenomatous polyposis coli; CK1, casein kinase 1; LRP5/6, low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5/6; TCF/LEF, T-cell factor/lymphoid enhancer-binding factor.

Research has demonstrated that the Wnt signaling pathway, particularly the

Wnt/-catenin signaling pathway, is important for

neurogenesis. This review aimed to consolidate existing studies pertaining to the

role of the Wnt/-catenin signaling pathway in neurogenesis throughout

developmental stages and in the adult brain. Additionally, we explored the

potential therapeutic implications of the Wnt/-catenin pathway in the

treatment of cerebral ischemia.

3. The Role of the Wnt/-catenin Pathway in Neurogenesis during

Brain Development

The Wnt/-catenin signaling pathway has diverse

functions throughout various stages of neural development. Overall, stimulation

of the Wnt/-catenin signaling pathway promotes neurogenesis and

suppresses gliogenesis [27, 28].

Chenn et al. [29] employed transgenic mice to induce

excessive activation of -catenin in neural precursors, resulting in the

identification of enlarged brains characterized by augmented cerebral cortical

surface area and folds, in addition to enlarged lateral ventricles lined with

neuroepithelial precursor cells. This outcome can be attributed to an increased

population of proliferative precursor cells [29]. Machon et al. [30]

employed a D6-Cre mouse strain to conditionally inactivate

-catenin (Ctnnb1) within the murine cerebral cortex

and hippocampus after embryonic day (E) 10.5. The results showed that

-catenin is needed for hippocampal progenitor proliferation, cortical

neuronal migration, late-embryonic cortical proliferation, and cortical radial

glial cell maintenance [30]. Additionally, several other studies have

demonstrated the indispensability of the Wnt pathway in the development of the

hippocampus [31, 32]. Furthermore, the Wnt/-catenin pathway plays a

crucial role in the early stages of cerebellar development and assumes a pivotal

function in governing differentiation within the cerebellar ventricular zone in

the subsequent stages of embryonic development [33].

In vitro, the introduction of exogenous Wnt3a protein enhanced the

proliferation and differentiation of NSCs isolated from the forebrain of E14.5

mice [34]. The inhibition of GSK-3 or the overexpression of

-catenin in ventral midbrain (VM) precursors leads to an increase in

neuronal differentiation and the quantity of dopaminergic (DA) neurons [35].

Furthermore, Wnt1 and Wnt3a promoted the proliferation of VM precursors obtained

from E14.5 rats, and Wnt5a induced the differentiation of DA precursors (from

either the cortex or VM) into DA neurons [36, 37]. These findings indicate that

Wnts serve as pivotal regulators of neurogenesis in the VM.

As described above, the Wnt/-catenin signaling pathway is known to play

a crucial role in brain development, particularly in neurogenesis. However, the

precise mechanism and downstream target genes involved in the promotion of

neurogenesis by Wnt/-catenin remain uncertain. Furthermore, the

complexity of the mechanism is further compounded by considerations of spatial

heterogeneity. A study revealed that -catenin plays a crucial role in

the proliferation and neuronal differentiation of neural progenitor cells.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) and luciferase reporter assays revealed that

-catenin binds directly to the promoter or proximal enhancer regions of

proneural genes, including neurogenin 1, neurogenin 2,

mash1, and myoD, resulting in their activation [38]. A separate

ChIP investigation revealed that the -catenin/T-cell factor 1 (TCF1) complex plays a

direct role in modulating the expression of Sox1, a marker of neural precursor

cells, in the context of neuronal differentiation in embryonic stem cells [39].

In addition, some articles suggest that the Wnt/-catenin signaling

pathway facilitates the proliferation of NSCs while inhibiting their

differentiation, thereby playing a role in the preservation of stem cell

characteristics [40, 41]. This disparity could be attributed to variations in the

culture conditions of neural progenitor cells, specifically the presence or

absence of Fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2) [38].

Taken together, these findings highlight the involvement of

Wnt/-catenin signaling in NSCs during development and imply that this

pathway may also facilitate adult neurogenesis and contribute to nerve

regeneration following cerebral ischemia.

4. The Role of the Wnt/-catenin Pathway in Adult Brain

Neurogenesis

4.1 Inhibition of the Wnt/-catenin Pathway Blocks Adult

Brain Neurogenesis

Wnt/-catenin signaling is activated in adult NSCs [42, 43].

Numerous published studies have

shown that the ablation of

Wnt/-catenin signaling impedes the proliferation of adult NSCs and their

subsequent differentiation into neurons. The overexpression of mutant Wnt1

protein in the DG led to reduced proliferation of adult hippocampal NSCs and

impaired generation of new neurons by suppressing Wnt signaling, consequently

impacting spatial memory and object recognition memory [44, 45].

Knockout of Wnt7a led to a

substantial decrease in the abundance of NSCs and an increase in the rate of cell

cycle termination in neural progenitors located in the DG and SVZ of adult mice.

Furthermore, Wnt7a plays a pivotal role in the process of neuronal

differentiation and maturation. The absence of Wnt7a expression led to a

noteworthy decrease in the number of newly formed neurons in the DG region of the

hippocampus [46, 47]. Another study showed that the suppression

of Wnt signaling through the knockdown of the Frizzled-1 receptor in the

hippocampus resulted in reduced neuronal differentiation of NSCs and altered

migration patterns of newly generated neurons [48].

However, Austin et al. [42] reported that conditional deletion of

-catenin in adult Glast-positive NSCs did not have any impact

on their maintenance, activation, or differentiation. Interestingly, a separate

investigation indicated that conditional knockout of

-catenin in Sox2-positive NSCs in the DG inhibited newborn

neuron generation and the survival of neuronal progenitors [49].

4.2 Activation of the Wnt/-catenin

Pathway Promotes Adult Brain Neurogenesis

In contrast to knockout of -catenin, conditional stabilization

of -catenin in mice resulted in the displacement of NSCs from the SGZ.

Additionally, in an in vitro model of hippocampal NSCs, the activation

of the Wnt/-catenin signaling pathway facilitated the differentiation of

active NSCs into neurons while also inducing the proliferation or differentiation

of quiescent NSCs in a dose-dependent manner [42]. Another

study indicated that the activation of the Wnt/-catenin signaling

pathway within the SVZ through the suppression of GSK-3 resulted in an

elevated quantity of nascent neurons within the olfactory bulb. This phenomenon

can be attributed to the increased proliferation of Mash1 progenitor cells

within the SVZ [50].

The observed phenotypes resulting from the activation of Wnt/-catenin

signaling in adult NSCs are consistent with other reports in

the literature. Activation of the Wnt/-catenin signaling pathway leads

to increased expression of NeuroD1 and long interspersed nuclear element 1 (LINE-1), both of which are pivotal in the

process of neuronal differentiation [49]. Overexpression of

Wnt7a and stabilized -catenin promote NSC

self-renewal in vitro. The introduction of -catenin

through lentiviral transduction resulted in an increase in the population of type

B NSCs within the SVZ of adult brains [46]. The overexpression of Wnt3in NSCs in vitro or in the DG in vivo promoted neuroblast

proliferation and neuronal differentiation [44]. In another study, the

overexpression of Wnt3a or Wnt5a was found to enhance the

proliferation and neuronal differentiation of neural progenitor cells derived

from postnatal and adult mouse brains [51]. In addition, the augmentation of

neurogenesis in the hippocampus was also observed upon the removal of Wnt

inhibitors [52, 53]. Moreover, the Wnt/-catenin signaling pathway plays

a significant role in the maturation of newborn neurons, as well as in the growth

of dendrites and the formation of dendritic spines in adult hippocampal neurons

[53, 54, 55].

In summary, the available evidence suggests that activation of the

Wnt/-catenin pathway in adult NSC niches promotes adult neurogenesis,

whereas the inhibition of this pathway hinders adult neurogenesis (Table 1, Ref.

[42, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55]).

Table 1.Evidence of the role of the

Wnt/-catenin pathway in adult brain neurogenesis.

| Signaling molecule |

Manipulation |

Effect on Wnt/β-catenin pathway |

In vivo/In vitro |

Phenotype |

Reference |

| Wnt1 |

overexpression of mutant Wnt1 |

inhibits |

in vivo |

inhibits hippocampal neurogenesis |

[44, 45] |

| Wnt7a |

knockout |

inhibits |

in vivo |

inhibits neurogenesis in DG and SVZ |

[46, 47] |

| Frizzled-1 |

knockdown |

inhibits |

in vivo |

inhibits hippocampal neurogenesis |

[48] |

| β-catenin |

knockout |

inhibits |

in vivo |

inhibits hippocampal neurogenesis |

[49] |

| Dickkopf-1 |

overexpression |

inhibits |

in vivo |

decreases proliferation of Mash1 progenitor cells within the SVZ |

[50] |

| β-catenin |

knockout |

inhibits |

in vivo |

inhibits dendritic development |

[55] |

| β-catenin |

stabilization |

activates |

in vivo |

promotes NSCs proliferation and their displacement from their correct SGZ location |

[42] |

| GSK-3β |

inhibition by CHIR99021 |

activates |

in vitro |

promotes neuronal differentiation of active NSCs and promotes the activation of quiescent NSCs |

[42] |

| β-catenin |

overexpression of stabilized β-catenin or inhibition of GSK-3β by Ro3303544 |

activates |

in vivo |

increases proliferation of Mash1 progenitor cells within the SVZ |

[50] |

| GSK-3β |

|

|

|

| Wnt7a |

overexpression of Wnt7a or stabilized β-catenin |

activates |

in vitro |

promotes NSCs self-renewal |

[46] |

| β-catenin |

| β-catenin |

overexpression of stabilized β-catenin |

activates |

in vivo |

increases numbers of type B NSCs in SVZ |

[46] |

| Wnt3 |

overexpression |

activates |

in vivo/in vitro |

promotes neuroblasts proliferation and neuronal differentiation |

[44] |

| Wnt3a |

overexpression |

activates |

in vitro |

enhances the proliferation and neuronal differentiation of neural progenitor cells |

[51] |

| Wnt5a |

| Dickkopf-1 |

knockout |

activates |

in vivo |

enhances hippocampal neurogenesis |

[52] |

| secreted frizzled-related protein 3 |

knockout |

activates |

in vivo |

promotes hippocampal neurogenesis, dendritic growth and spine formation |

[53] |

| β-catenin |

stabilization |

activates |

in vivo |

accelerates dendritic growth, but eventually causes dendritic defects and excessive spine numbers |

[54] |

DG, dentate gyrus; SGZ, subgranular zone.

5. The Role of the Wnt/-catenin Pathway in

Neurogenesis after Cerebral Ischemia

The occurrence of cerebral ischemia leads to the stimulation of NSCs in the SVZ,

resulting in their increased proliferation and subsequent asymmetric division

into migratory neuroblasts. These neuroblasts subsequently migrate toward

ischemic regions, where they undergo differentiation into

neurons, potentially facilitating functional recovery. Additionally, NSCs in the

SGZ can migrate to the granular cell layer and differentiate into new neurons,

potentially reversing the learning and memory deficits caused by ischemia.

However, it should be noted that this reparative mechanism is insufficient to

fully compensate for the extensive damage caused by severe cerebral ischemia [8, 13]. Studies have indicated that the Wnt/-catenin

pathway within adult NSC niches facilitates neurogenesis following cerebral

ischemia and contributes to the restoration of neurological function (Table 2,

Ref. [56, 57, 58, 59]).

Table 2.Evidence of the role of the Wnt/-catenin pathway in

neurogenesis after cerebral ischemia.

| Signaling molecule |

Manipulation |

Effect on Wnt/-catenin pathway |

In vivo/In vitro |

Phenotype |

Reference |

| -catenin |

knockdown |

inhibits |

in vivo |

inhibits neurogenesis in SVZ and increases infarct volume |

[56] |

| Dickkopf-1 |

overexpression |

inhibits |

in vitro |

inhibits neuronal differentiation of NSCs derived from the SVZ of middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) mice |

[57] |

| Wnt3a |

overexpression |

activates |

in vivo |

increases neurogenesis and promotes neurological function recovery |

[58] |

| Wnt3a |

overexpression |

activates |

in vivo |

promotes neurogenesis in SGZ and SVZ, decreases infarct volume, and enhances sensorimotor functions |

[59] |

5.1 Inhibition of the Wnt/-catenin Pathway Impedes

Neurogenesis Subsequent to Cerebral Ischemia

Lei et al. [56] administered -catenin Small interfering RNA (siRNA)

intracerebroventricularly to mice subjected to transient middle cerebral artery

occlusion (tMCAO) to deactivate -catenin, leading to an increase in

infarct volume and a decrease in neurogenesis within the SVZ. The administration

of -catenin siRNA resulted in a significant reduction in the

populations of 5-Bromo-2-deoxyuridine (BrdU)/3-tubulin (Tuj1) cells, BrdU/Doublecortin (DCX) cells, and

BrdU/Microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2) cells within the ischemic striatum, which serve as markers

for newborn immature neurons, proliferating progenitors, and newborn mature

neurons, respectively [56]. Furthermore, the use of a genetic

approach to induce the overexpression of the Wnt inhibitor Dickkopf-1 (DKK1) in NSCs derived

from the SVZs of mice subjected to MCAO suppressed neuronal differentiation [57].

5.2 Activation of the Wnt/-catenin Pathway Promotes

Neurogenesis after Cerebral Ischemia and is Beneficial for Ameliorating Nerve

Function Injury following Cerebral Ischemia

The increase in Wnt3a levels within the SVZ or striatum of mice afflicted with

focal ischemic injury was found to play a significant role in facilitating

functional recovery subsequent to the ischemic event. This was achieved through

the promotion of neurogenesis or the enhancement of neuronal viability [58]. A

separate study demonstrated that the intranasal administration of

Wnt3a subsequent to focal ischemic stroke in mice reduced

infarct volume, augmented sensorimotor functions, stimulated neurogenesis in the

SVZ and SGZ, increased the number of DCX/BrdU colocalized cells

migrating from the SVZ toward the peri-infarct area, and increased the quantity

of newly formed neurons (BrdU/NeuN cells) in the peri-infarct zone.

Conversely, intranasal administration of a Wnt inhibitor hindered neurogenesis

and decreased the quantity of newly generated neurons in the peri-infarct area

[59].

In addition, studies have revealed that some treatments and mechanisms can

further upregulate the Wnt/-catenin pathway after cerebral ischemia,

thereby promoting neurogenesis and contributing to the reinstatement of

neurological function [60, 61, 62, 63, 64]. Taken together, these findings indicate that the

activation of the Wnt/-catenin pathway subsequent to cerebral ischemia

has the potential to stimulate neurogenesis and ameliorate nerve function

impairment, making this pathway a viable therapeutic target for the management of

cerebral ischemia.

6. Limitations in the Available Studies on the Role

of the Wnt/-catenin Pathway in Postischemic Neurogenesis

As stated above, considerable advancements

have been made in the field of research pertaining to genetic or pharmacological

interventions in the Wnt/-catenin pathway aimed at increasing

neurogenesis following cerebral ischemia.

However, most studies lack a

quality study design. Many published studies utilized immunofluorescence

colocalization of BrdU with neuronal markers or neuroblastic markers to evaluate

neurogenesis and the de novo generation of neurons.

However, it is unclear whether these proliferative cells were derived from NSCs.

Previous studies have reported that astrocytes can transdifferentiate into

morphologically mature and functional neurons after cerebral ischemia [65].

Therefore, it is recommended that researchers employ lineage tracing techniques

in future studies to track the fate of NSCs to elucidate their

potential contributions to brain neurogenesis and postischemic stroke recovery.

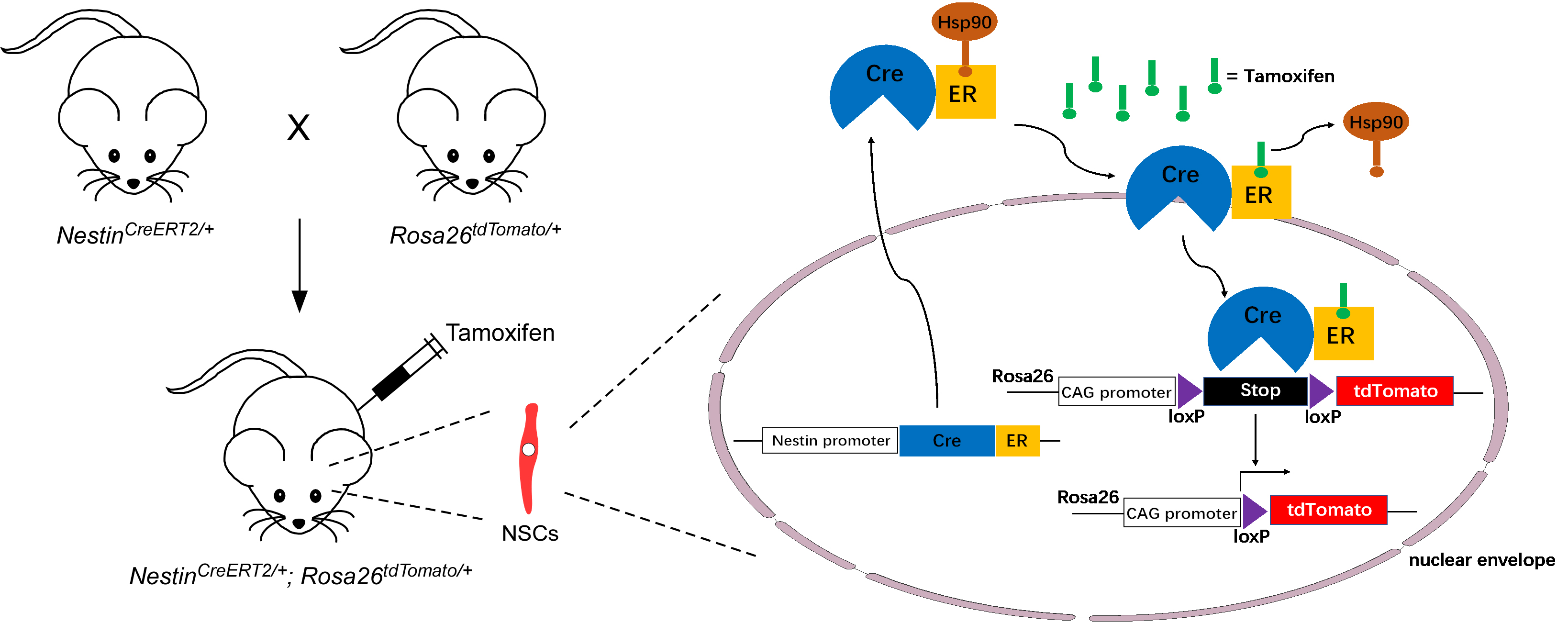

Lineage tracing serves as a valuable tool for investigating the origin of new

neurons in ischemic regions, specifically whether they originate from NSCs within

the adult NSC niche. Additionally, it enables the examination of the impact of

the Wnt/-catenin signaling pathway on the cellular fate of different NSC

populations. Currently, numerous techniques are available for lineage tracing

(for review, see [66]), with one of the most prevalent approaches involving the

integration of the Cre mouse line in combination with the

Rosa26-CAG-reporter mouse line. For adult NSC lineage

tracing, researchers can cross inducible NSC-specific Cyclization recombination enzyme (Cre) lines, such as

Nestin-CreERT2 mice [67] and Ascll-CreERT2 mice [68], with

Rosa26-CAG-reporter lines, such as Rosa26-CAG-tdTomato mice

[69], to generate

Nestin;

Rosa26 mice or Ascll;

Rosa26 mice. With tamoxifen administration, the NSCs in

lineage-traced mice exhibit stable expression of tdTomato, enabling the tracking

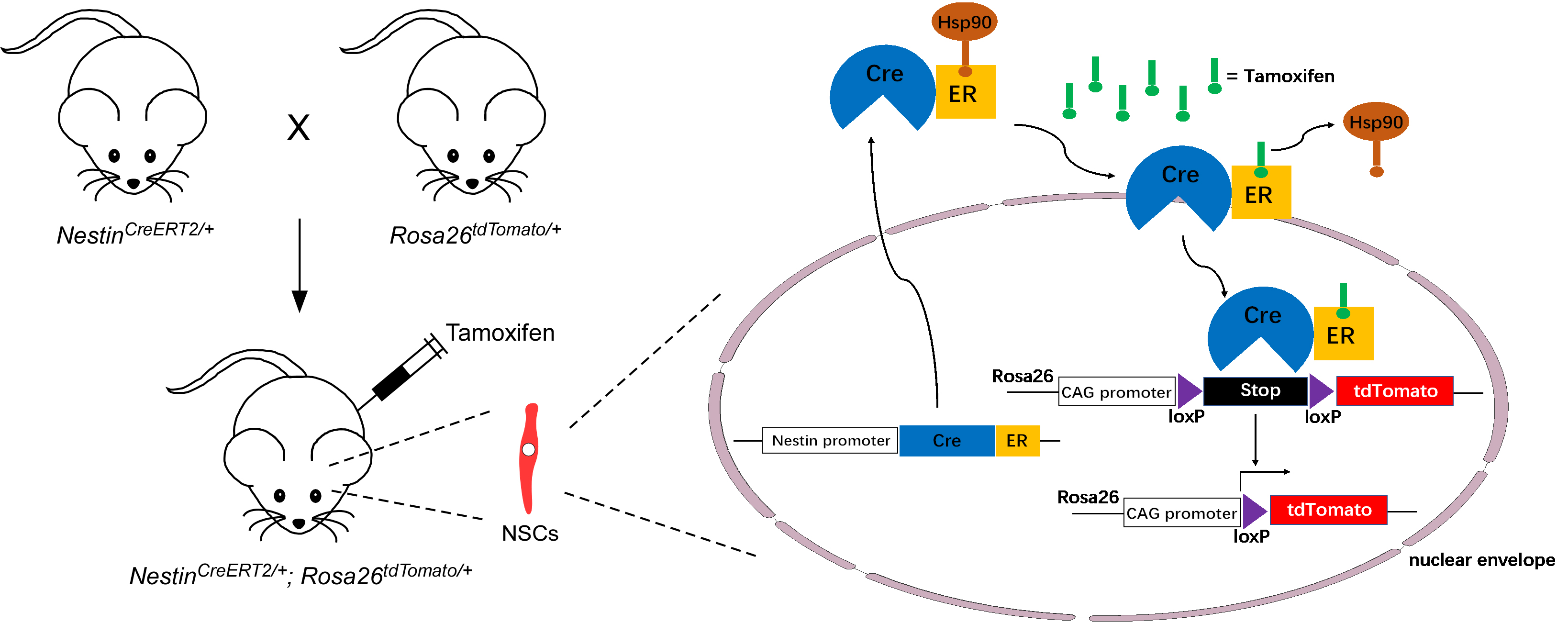

of the fate of cells originating from the NSC niche (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Schematic protocol for lineage tracing of Nestin-positive adult NSCs. Nestin;

Rosa26 mice are generated by crossing

Nestin-CreERT2 mice with Rosa26-CAG-tdTomato mice. Upon the

administration of tamoxifen to Nestin;

Rosa26 mice, Hsp90 is displaced from CreER, allowing Cre

recombinase to enter the nucleus of Nestin-positive adult NSCs. Subsequently, the

Cre recombinase removes the loxP-Stop-loxP cassette, resulting in

permanent tdTomato expression in adult NSCs. ER, Estrogen receptor; CAG, cytomegalovirus enhancer plus chicken beta-actin promotor.

There are additional limitations in studies on the role of the

Wnt/-catenin pathway in postischemic neurogenesis. All current studies

on the Wnt/-catenin pathway in postischemic neurogenesis have been

conducted using animal models. Given the ongoing debate surrounding human adult

neurogenesis, the transition from preclinical research to clinical trials for the

treatment of ischemic stroke through the activation of the Wnt/-catenin

pathway presents significant obstacles. In addition, the potential of agonists of

Wnt/-catenin signaling to enhance neurogenesis following cerebral

ischemia remains uncertain. The preclinical exploration of Wnt/-catenin

signaling agonists holds significance for their eventual clinical utility.

7. Conclusion

Ischemic stroke is characterized by

increased morbidity, disability, recurrence, and mortality. Intravenous

thrombolysis and thrombectomy are approved medical treatments for acute stroke.

However, it is crucial to acknowledge the limited timeframe within which these

therapies can be administered, as well as the potential for intracerebral

hemorrhage and other bleeding complications that may arise from the utilization

of intravenous thrombolysis and mechanical thrombectomy. Thus, there is a need

for the development of new treatments. Researchers have focused

on endogenous NSC-induced neurogenesis following ischemic stroke

due to the demonstrated positive impact of

NSCs on neural repair. According to existing studies, the

modulation of numerous signaling pathways has been found to facilitate NSC

proliferation and differentiation while also

augmenting angiogenesis and synaptic plasticity. These mechanisms collectively

contribute to the process of neural repair subsequent to ischemic brain injury.

Based on the existing evidence, the Wnt/-catenin pathway is a promising

therapeutic target for alleviating the consequences of ischemic stroke. The

activation of this pathway facilitates neurogenesis, leading to the generation of

newly formed neurons that can replace deceased neural cells within the ischemic

core. Future studies should further investigate whether the newly generated

neurons are functional in vivo and whether they can integrate with

existing neural circuits. Furthermore, additional in-depth lineage tracing

experiments should be conducted.

Author Contributions

JDX and LSC designed the study. JDX wrote the manuscript and draw Figures and

Tables; LSC revised the manuscript; SYL, LXX, YNZ, and WRJ collected and sorted

references, as well as provided comments to improve the manuscript. All authors

contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved

the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and

agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Acknowledgment

Not applicable.

Funding

This research was funded by Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of

China (Grant No. LQ23H280003 and LQ23H280006) and Research Project of Zhejiang

Chinese Medical University (Grant No. 2021RCZXZK08 and 2021RCZXZK06).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.