1 First Clinical Medical College, Shaanxi University of Chinese Medicine, 712046 Xianyang, Shaanxi, China

2 The Department of Traditional Chinese Medicine, the First Affiliated Hospital of the Air Force Military Medical University, 710038 Xi’an, Shaanxi, China

3 Department of Cardiology, Affiliated Hospital of Shaanxi University of Chinese Medicine, 712000 Xianyang, Shaanxi, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

The coexistence of anxiety or depression with coronary heart disease (CHD) is a significant clinical challenge in cardiovascular medicine. Recent studies have indicated that hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis activity could be a promising focus in understanding and addressing the development of treatments for comorbid CHD and anxiety or depression. The HPA axis helps to regulate the levels of inflammatory factors, thereby reducing oxidative stress damage, promoting platelet activation, and stabilizing gut microbiota, which enhance the survival and regeneration of neurons, endothelial cells, and other cell types, leading to neuroprotective and cardioprotective benefits. This review addresses the relevance of the HPA axis to the cardiovascular and nervous systems, as well as the latest research advancements regarding its mechanisms of action. The discussion includes a detailed function of the HPA axis in regulating the processes mentioned. Above all, it summarizes the therapeutic potential of HPA axis function as a biomarker for coronary atherosclerotic heart disease combined with anxiety or depression.

Keywords

- anxiety

- CHD

- depression

- HPA axis

- mechanism of action

Coronary heart disease (CHD) results from a decrease in blood flow to the heart

due to narrowing or blockage of the coronary arteries, leading to myocardial

ischemia, hypoxia, necrosis, inflammation, and apoptosis of cardiomyocytes [1].

Ischaemic heart disease alone caused 7 million deaths worldwide in

2010, an increase of 35% since 1990 [2], resulting in an annual mortality rate of 1.9 million

people, thus making it the primary cause of death in China [3]. Research has

indicated that depression is now the second most common cause of mortality

worldwide, after CHD. Depression has emerged as a distinct risk factor alongside

traditional factors for CHD, such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes

mellitus, smoking, and obesity [4]. Anxiety and depression, recognized as

independent risk factors, can exacerbate CHD. Long-term medication in patients

with CHD can lead to anxiety or depression, or both, and anxiety or depression

leads to over-activation of the sympathetic nervous system, increasing the

cardiac load and exacerbating CHD, thus creating a vicious cycle. In recent

years, the incidence of depression or anxiety in combination with CHD, has been

gradually increasing, and has led to huge medical costs and adverse events, which

has imposed a heavy burden on society [5]. Furthermore, a cross-sectional study involving almost 8000 patients who had been

previously hospitalized for a coronary event showed that the incidence of

depressive symptoms was 30.6% among women and 19.8% among men, during the

period from 2012 to 2014 [6]; it was found that 12% exhibited clinical

depression (depressive disorder) at baseline, and 45% displayed subclinical

depression (Patient Health Questionnaire-9, PHQ-9, score

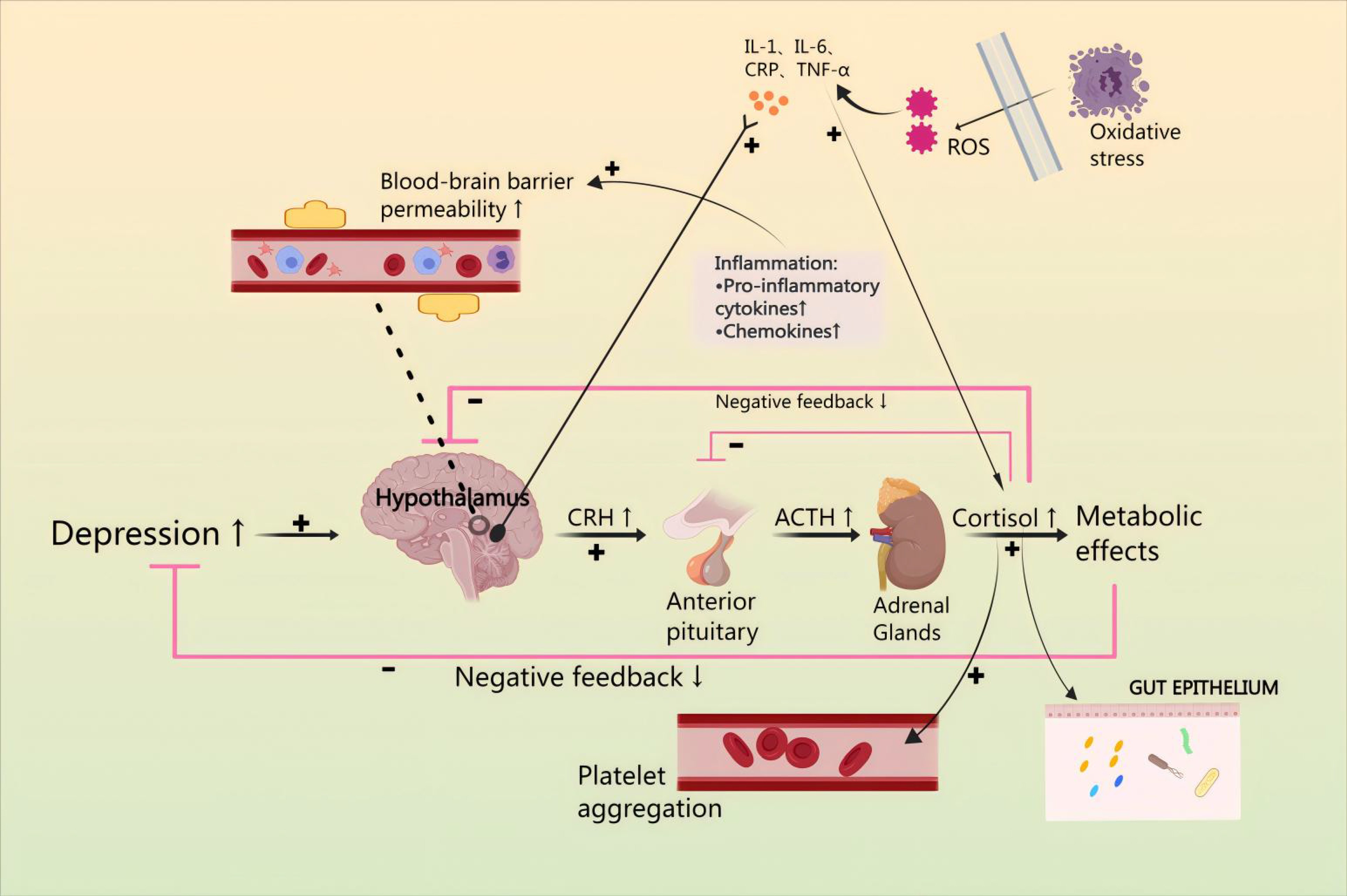

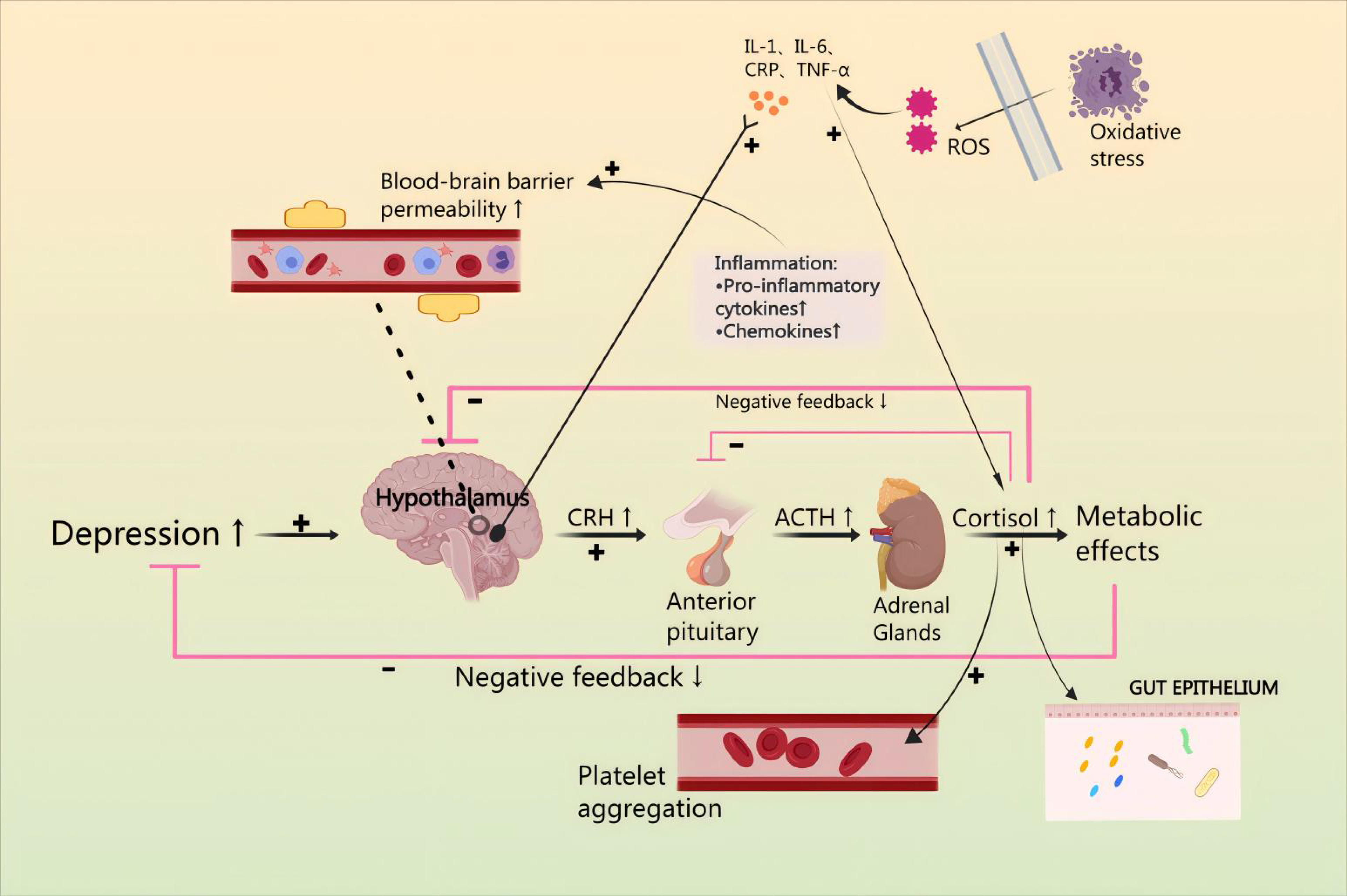

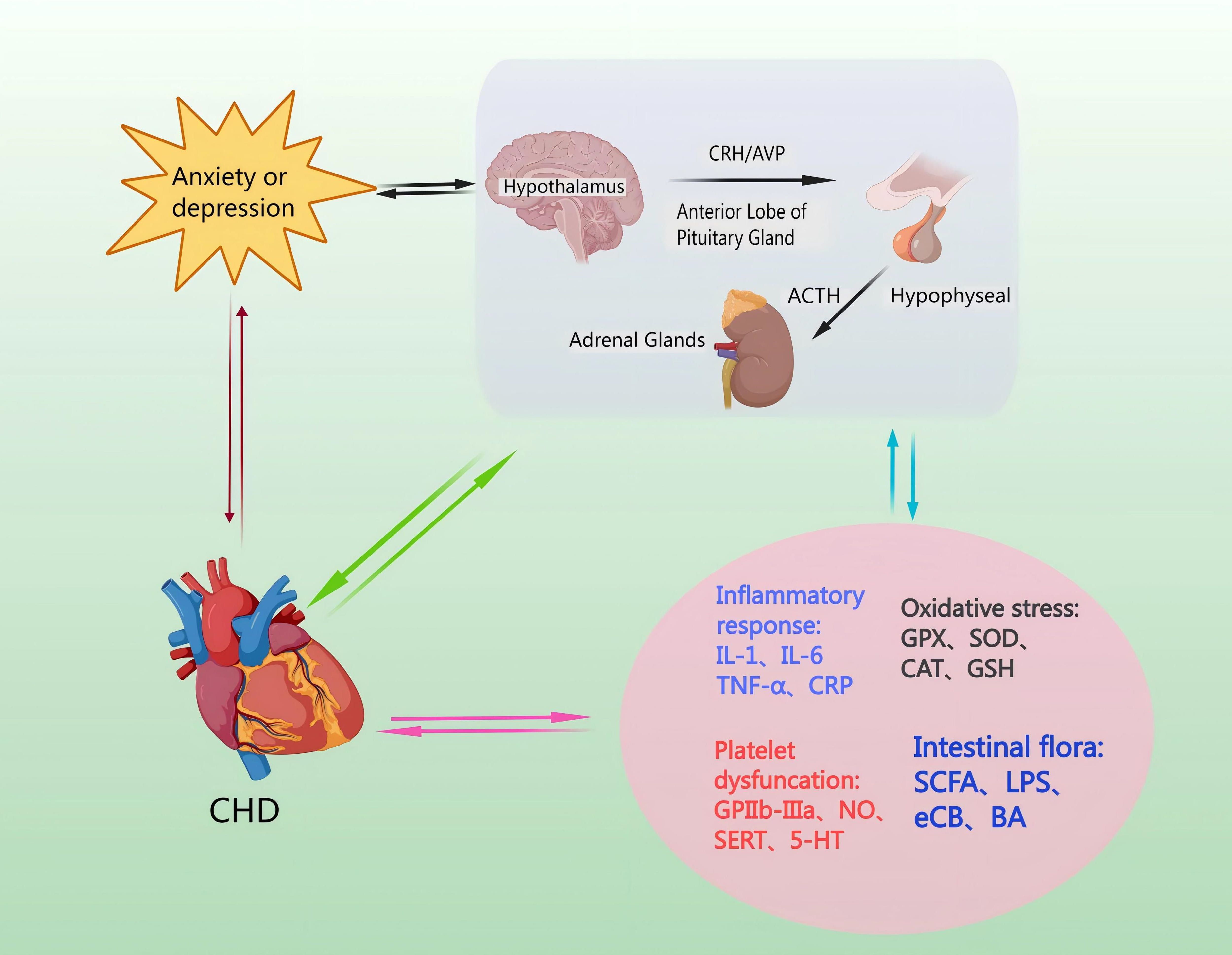

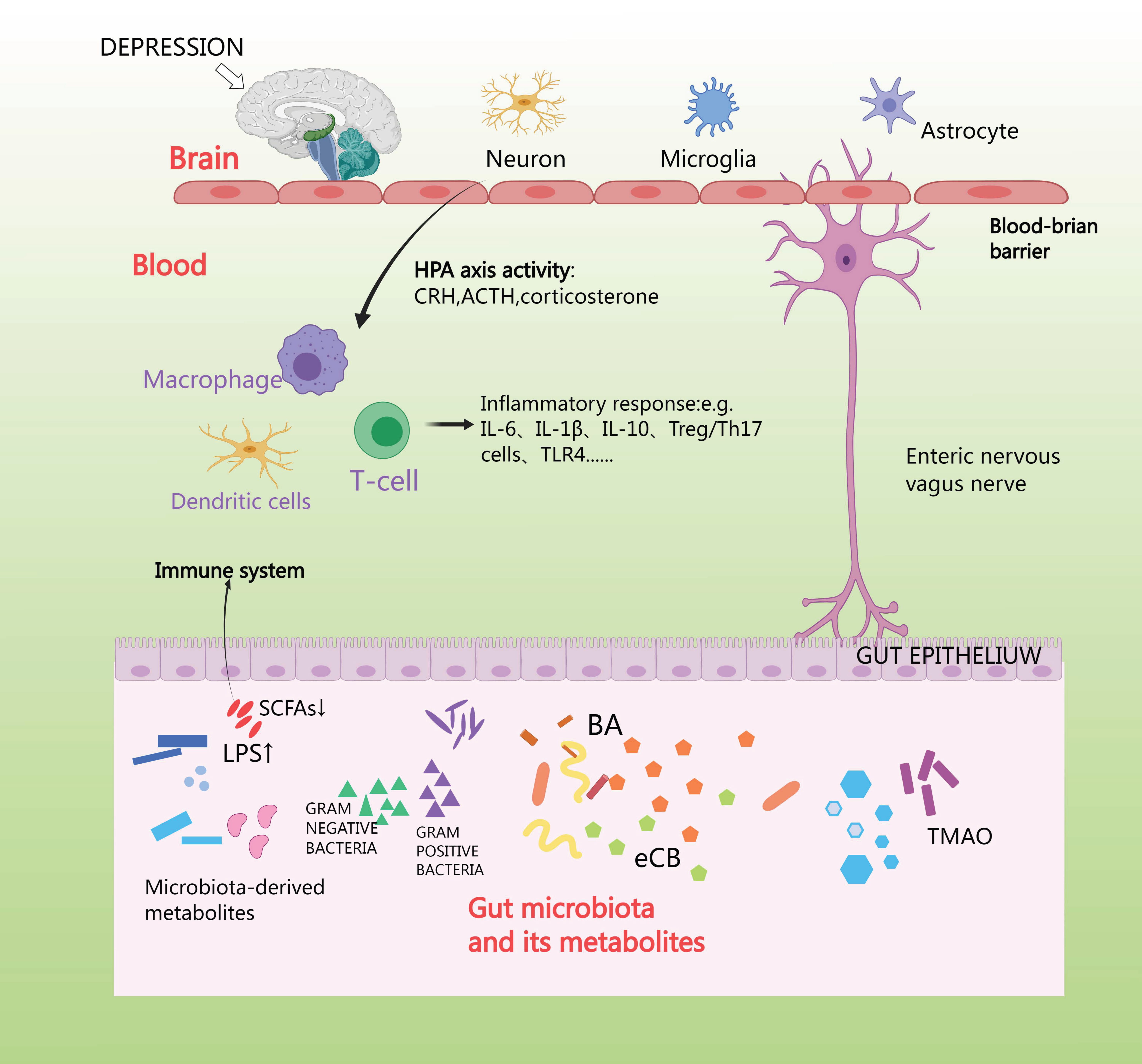

Contemporary medical science holds various perspectives regarding the development of CHD in conjunction with anxiety or depression, such as platelet activation, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal cortex (HPA) axis hyperfunction, vascular endothelial dysfunction, intestinal flora dysbiosis, and reduced synthesis of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) [11]. In most cases, the HPA axis is the neuroendocrine mediator of neural and behavioral responses to stress [12]. From a mechanistic perspective, corticotropin releasing factor (CRH) released from the hypothalamus binds to CRH1 and CRH2 receptors in the anterior pituitary. This activates the secretion of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) into the somatic circulation, resulting in a release of glucocorticoids from the adrenal cortex, and activates a negative feedback loop involving cortisol. Dysfunction of this system is associated with increased risk of depression and anxiety disorders [13]. It is noteworthy that interleukin-1 (IL-1) triggers the release of CRH from the paraventricular nucleus (PVN), subsequently leading to the secretion of ACTH from the anterior pituitary, which in turn stimulates the secretion of glucocorticoids (GC) from the adrenal cortex [14, 15]. Since cytokines are released as part of the inflammatory response, they potentially exert inhibitory effects on the expression of the HPA axis. CHD has the potential to induce damage and inflammation in endothelial cells [16]. Furthermore, excess cortisol leads to ‘leaky gut’ by modulating the gut barrier function and inflammatory response. As expected, stimulation of the HPA axis may lead to changes in the microbiota composition, heightened permeability of the intestines, and disturbance of the microbiota, leading to neuroendocrine disruption, enhancement of intestinal permeability, and disorders of the composition of the microbiota, which will trigger neuroendocrine dysregulation and lead to CHD combined anxiety or depression. Thus, cytokines, released by the inflammatory response in patients with CHD, may lead to increased oxidative stress, promote platelet activation, and lead to intestinal dysbiosis, finally resulting in HPA axis hyperactivity, thereby producing anxiety or depression [17] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Mechanisms by which the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA)

axis affects combined anxiety or depression and coronary heart disease (CHD).

Anxiety or depression are affected by the HPA axis by modulation of inflammatory

factor levels, reduction of oxidative stress damage, enhancement of platelet

activation, and maintenance of the stability of gut microbiota. IL, Interleukin;

CRP, C-reactionprotein; TNF-

Anxiety or depression, through modification of the HPA axis, can cause endothelial damage and promote the occurrence and development of CHD, which may affect the inflammatory response, oxidative stress, platelet activation, and intestinal flora dysbiosis [18]. First, the relevance of the HPA axis to the cardiovascular and nervous system function cannot be overstated: glucocorticoids (GC) can not only affect cell proliferation, cellular survival, and movement of cells by regulating anti-angiogenic platelet reactive protein-1 via glucocorticoid receptors (GR), but also, vasoconstriction and relaxation are regulated by the HPA axis [19]. Second, in the neuroendocrine system, arginine vasopressin (AVP) secretion is increased by secreted ACTH; this induces increased GR release and increased cortisol release [20]. The HPA axis in the comorbidity of anxiety or depression and CHD, focuses on the precise mechanisms by which the HPA axis modulates inflammatory-factor levels, reduces oxidative stress damage, enhances platelet activation, and maintains the stability of gut microbiota. CHD pathomechanisms can lead to hyperactivity of the HPA axis, causing anxiety or depression. Based on the foregoing, we examined the effects of the HPA axis as possible contributors to CHD in combination with anxiety or depression.

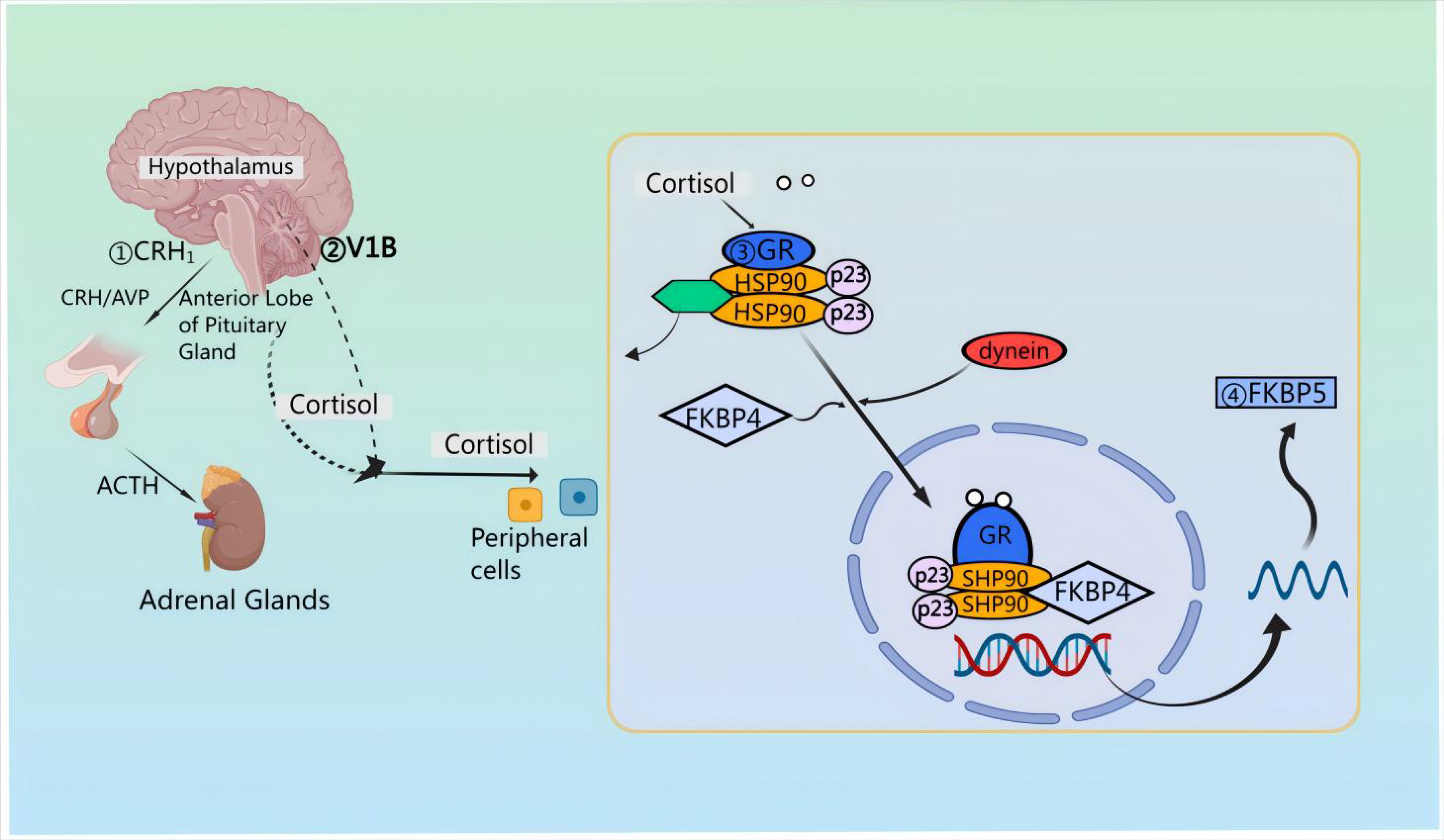

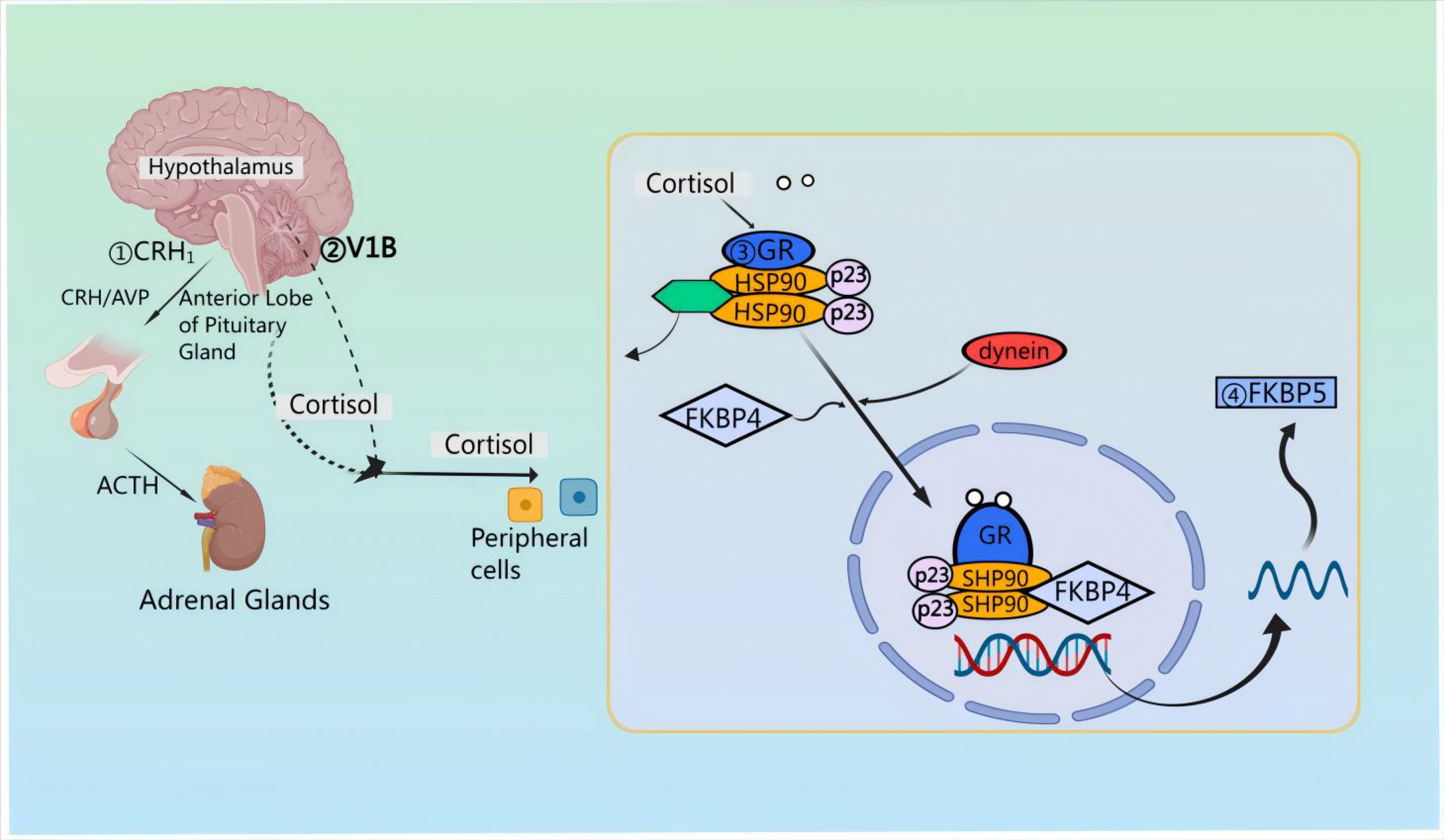

First, pro-pituitary neurons in the PVN of the hypothalamus release CRH and AVP [21]. Then, CRH and AVP are discharged into the median eminence and transported to the anterior pituitary via the pituitary portal vessels [22, 23, 24]. Upon reaching the anterior pituitary, CRH attaches to the CRF type 1 receptor (CRFR 1) situated on pituitary corticotropin cells [25, 26]. Notably, CRH also signals through CRFR 2 in cardiac myocytes, stimulating cardiac and cerebral natriuretic hormone production during cardiac hypertrophy [27]. The binding of CRH to CRFR 1 results in ACTH synthesis originating from preopiomelanocortinogen (pre-POMC) and stimulates the release of ACTH into the systemic circulation [28, 29, 30]. After release, ACTH attaches to the melanocortin type 2 receptor (MC 2-R) located in the adrenocortical z. reticulata, triggering the synthesis of the kinetic hormone glucocorticoid (GC) [cortisol (in humans) or corticosterone (in rat)] which is then stored in and released from the adrenocortical z. fascilulata [31, 32]. Apart from this, upon stimulation by CRH and AVP, the release of ACTH involves distinct second messenger systems. Specifically, CRH triggers G-protein-linked adenylate cyclase, resulting in the formation of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and subsequent activation of protein kinase A [33]. FK 506-binding protein 51 (FKBP 51) is essentially regulated by FKBP 5 encoding [34]; when FKBP 51 binds to the GR complex, GC binding affinity is reduced and GR translocation to the nucleus is less efficient [35]. The activation of the GR leads to an increase in FKBP 5 mRNA and protein expression, establishing a very brief negative feedback loop [36]. In the absence of ligands, the GR complex is composed of co-molecular chaperones FKBP 51 or FKBP 52, encoded by their respective genes, along with p23 as a co-molecular chaperone molecule. Upon binding to GC, FKBP 51 is replaced by FKBP 52, facilitating the nuclear translocation of the ligand-bound GR [37]. GR directly interacts with DNA through the GC-responsive element, inducing the expression of FKBP 5 mRNA and subsequently inducing the production of FKBP 51 [38], thereby inducing an ultrashort negative feedback loop of GR sensitivity [39] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Mechanisms of action of the HPA axis in neuroprotection. Corticotropin releasing factor (CRH) attaches to corticotropin releasing factor (CRF) type 1 receptor (CRFR 1) situated on pituitary corticotropin cells; CRH triggers G-protein-linked adenylate cyclase, resulting in the formation of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and subsequent activation of protein kinase A. AVP, arginine vasopressin; GR, glucocorticoid receptors; FKBP, FK 506-binding protein; HSP90, heat shock protein 90.

Hippocampal neuron apoptosis is closely associated with depression. However, some studies suggest that there is a reciprocal relationship between the excessive activity of the HPA axis and the production of BDNF. Influenced by the activation of nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/Akt) can promote the expression of the hypothalamic neuropeptide W mRNA in hypothalamic neurons. HPA axis thereby can lead to anxiety and depression.

Altered neuroendocrine function in depression results in the activation of the HPA axis and sympathetic nervous system, leading to the release of angiotensin II and glucocorticoids. Ultimately, the activation of the GR leads to an increased risk of CHD. When CRH is administered, it causes an increase in heart rate and cardiac output, leading to elevated arterial pressure by stimulating the release of norepinephrine (NE) and epinephrine (E). There is growing evidence indicating that CRH may directly regulate nitric oxide (NO)-dependent vasodilation and vascular permeability [40]. Also, CRH activates CRFR 2 in heart muscle cells, promoting the production of natriuretic peptides in the heart and brain during cardiac hypertrophy [41]. Further study is necessary to gain a comprehensive understanding of the variances in downstream signaling activated by CRH binding to CRFR 1 and CRFR 2 [42]. AVP, binding to V1 R on smooth muscle cells, results in increased activation of K+ channels sensitive to ATP and decreased NO synthesis. This relates to the ability of AVP to induce either coronary vasoconstriction or vasodilation [43]. Moreover, sympathetic hyperadrenalism in depression leads to elevated plasma catecholamines, vasoconstriction, increased heart rate, and platelet activation; increased adrenergic and other vasoconstrictors help restore vascular tone [44, 45]. One study reported that vascular endothlial growth factor (VEGF) functions as an additional inflammatory indicator, releasing stimulated IL-6 and inhibiting GC. When testing depressed and non-depressed groups, the authors found that individuals with CHD who were depressed exhibited significantly higher plasma VEGF levels (almost double) than did non-depressed individuals with CHD [46]. In sum, GC inhibits vasodilator production through GR activation, enhancing the response of vascular smooth muscle cells to catecholamines and other vascular activators [47].

In vivo findings also indicated that the administration of GC resulted

in hypertension in mice by means of GR inhibiting the NO metabolites NO2-

and NO3- [48], additionally, the authors observed that pro-inflammatory

cytokines Tumor Necrosis Factor-

In future research, it will be important to investigate the systemic impact of ACTH on the vascular system. GR has a direct impact on endothelial function through the regulation of adhesion molecules like vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1), as well as proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines that result in the production of IL-6, IL-8, and C C motif ligand 2 (CCL 2) (Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1, MCP-1). Furthermore, this influences vasodilator NO and vasoconstrictors [angiotensin II (Ang II) or endothelin 1 (ET-1)], thereby contributing to the maintenance of endothelial structure and responsiveness.

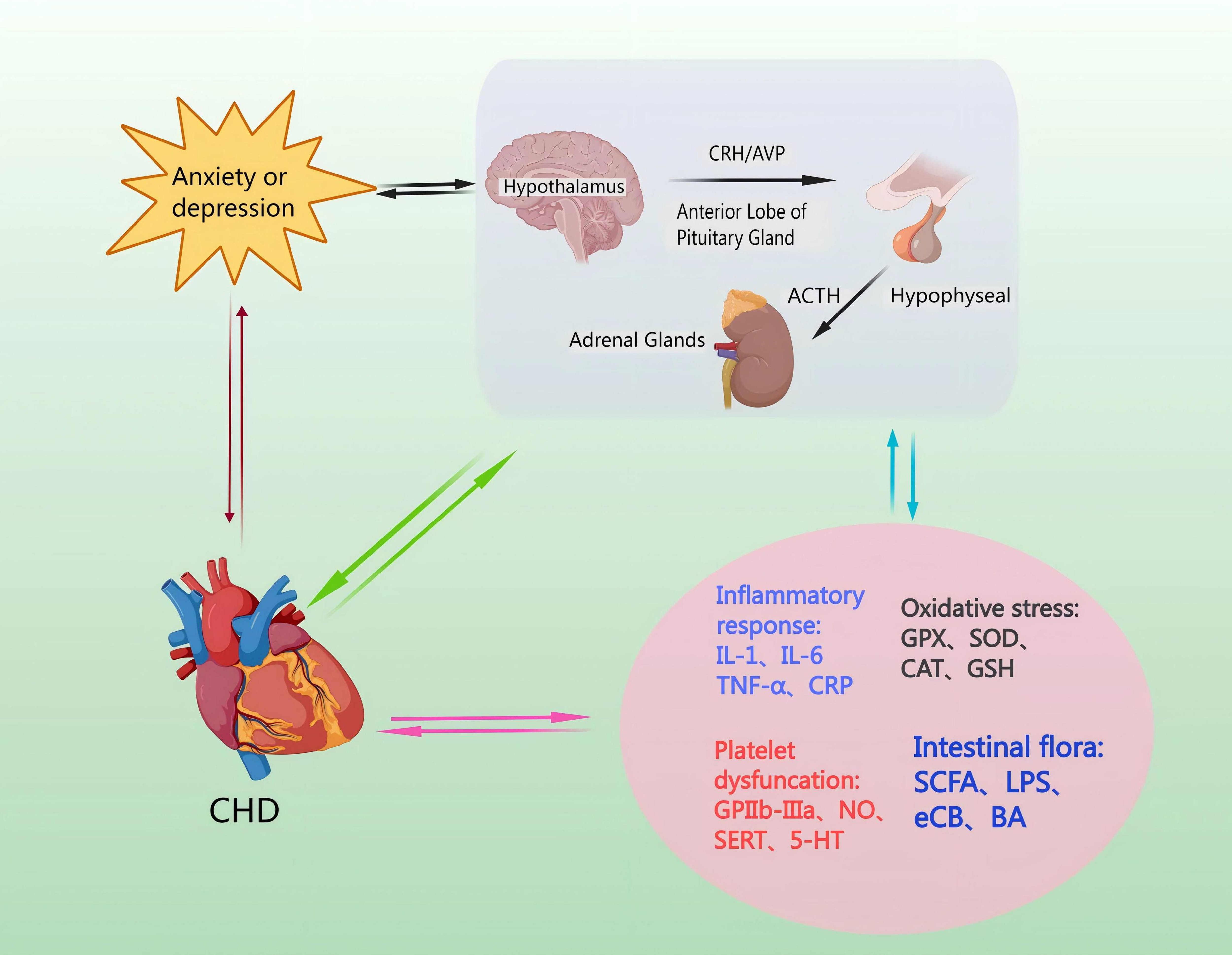

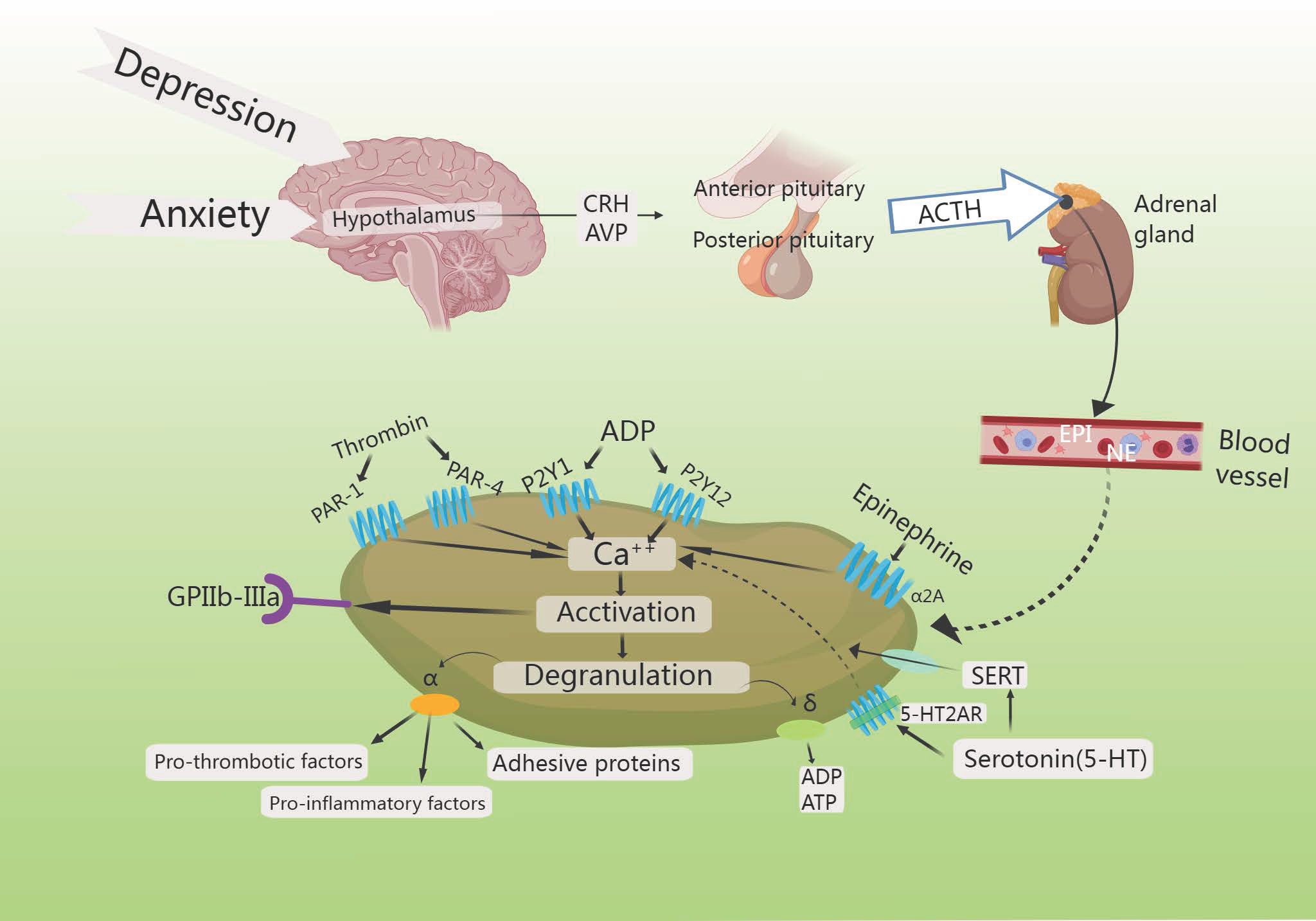

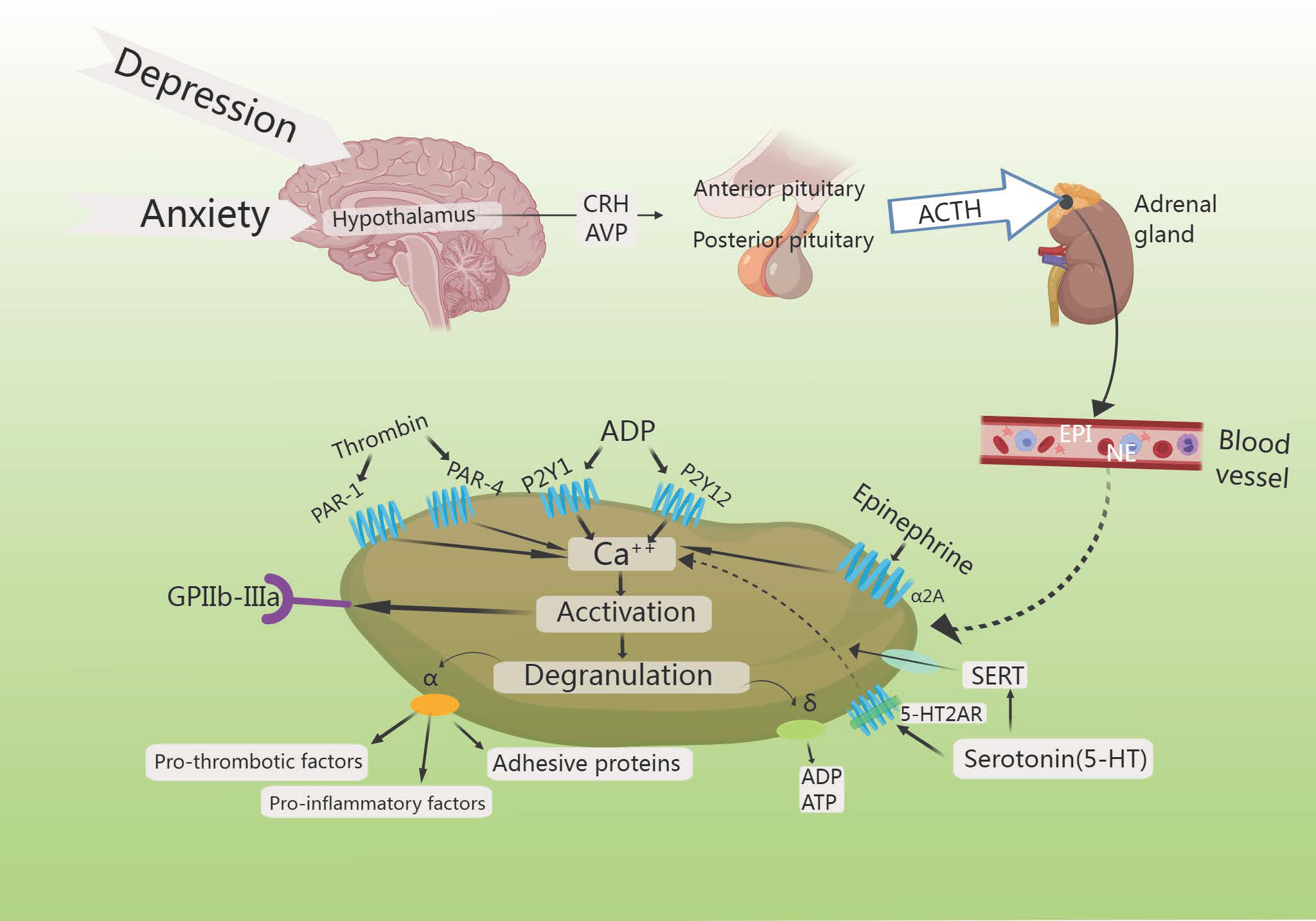

Catecholamines are released from the neurons and the adrenal medulla [53]. This leads to ACTH secretion from the hypothalamus and mediates the release of corticosterone (CORT) from the adrenal cortex via a negative feedback loop, and inhibits CRH and ACTH secretion [54]. Moreover, GC feedback blocks ACTH release from the pituitary, and sympathetic activation enhances adrenal GC production [55]. The amygdala’s subnucleus indirectly influences HPA axis responses by transmitting signals through a gamma-aminobutyric acid-ergic (GABAergic) relay to PVN projection neurons in the hypothalamus and the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BST), resulting in disinhibition [56]. Specifically, AVP enhances CRH action downstream, and pituitary trophic PVN CRH neurons send projections to the outer plate of the median eminence. Here, CRH and co-stored peptide/transmitter are released into the portal vein, subsequently entering the anterior pituitary for ACTH release [57]. ACTH then travels to the adrenal cortex via somatic circulation, stimulating GC synthesis and secretion to complete an effective three-step amplification process [58]. The neuroendocrine stress response is regulated in a counteractive manner by circulating GC, which utilizes negative feedback mechanisms to target the pituitary, hypothalamus, and hippocampus, in that the adrenal cortex produces cortisol, which penetrates the blood-brain barrier and acts in the brain via high-affinity salinocorticoid receptors and low-affinity GC receptors to produce anxiety and depression [59] (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Mechanisms by which the HPA axis regulates levels of inflammatory factors, induces oxidative stress injury, increases platelet activation, and affects intestinal flora. CHD pathomechanisms can lead to hyperactivity of the HPA axis, causing anxiety and depression. Anxiety or depression, through the HPA axis, can cause endothelial damage and promote the occurrence and development of CHD. NO, nitric oxide; SERT, Serotonin transporter; 5-HT, 5-Hydroxytriptamine; GPX, Glutathione peroxidase; SOD, superoxide dismutase; CAT, catalase; GSH, Glutathione; SCFA, short-chain fatty acid; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; eCB, endocannabinoid; BA, bile acids; GPIIb-IIIa, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptors.

AVP has been shown to inhibit the CRH-stimulated POMC gene phenotype in proadrenocorticotropic due to sympathetic adrenal activation, and higher concentrations of NE and E were observed in cardiac patients. CRH concentrations were significantly higher in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of medication-free patients suffering from major depressive disorder and victims of suicide than in patients with other psychiatric disorders and in healthy controls. The findings strongly suggested that alterations related to GR could potentially be linked to the development of depression [60]. Eventually, CORT suppressed cardiomyocyte apoptosis that was triggered by ischemia and hypoxia, yet the likelihood of major cardiovascular adverse events (MACE) rose significantly when anxiety-depression led to an excessive surge in cortisol levels [61].

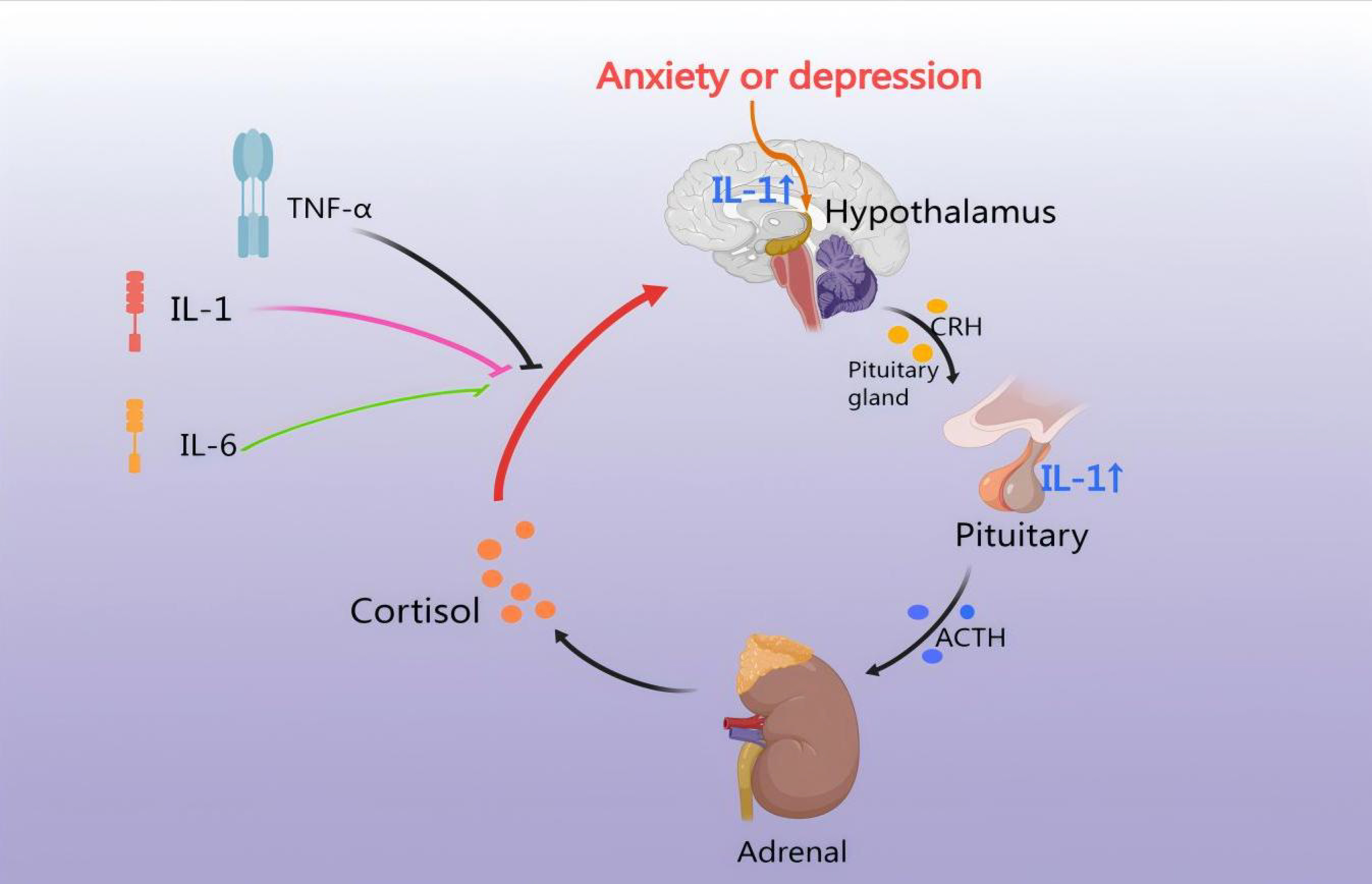

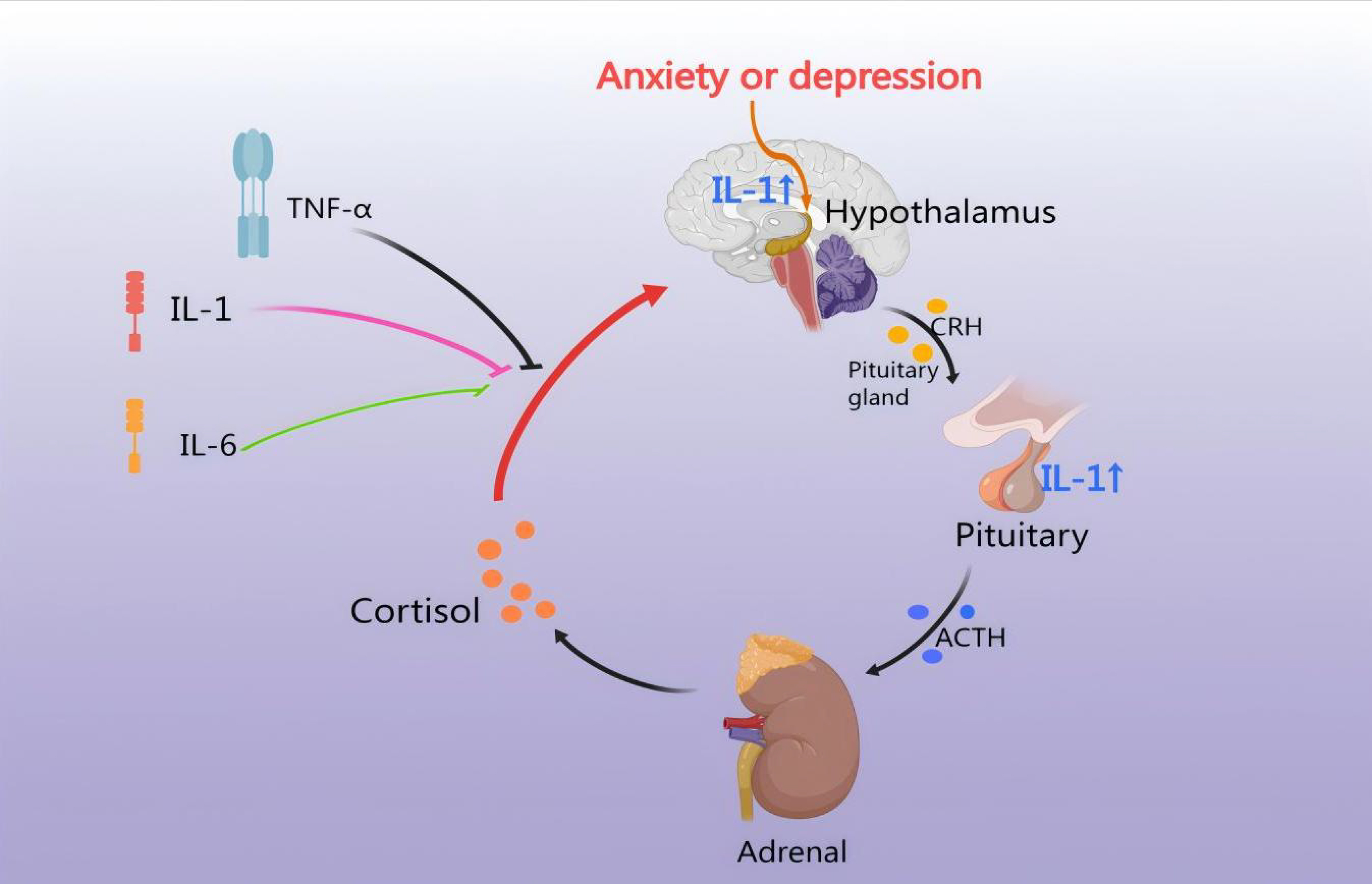

CHD involves stenosis and plaque formation in the coronary arteries, potentially

leading to an inflammatory response. Similarly, medication may contribute to

intimal irritation, increasing the risk of an endovascular inflammatory response.

Therefore, anxiety and depression disorders are interconnected and can lead to an

inflammatory response [62]. IL-1 directly induces pituitary secretion of ACTH and

subsequent adrenal secretion of CORT via the IL-1 type I receptor (IL-1 RI).

Neuropeptides are found in numerous CRH-producing neurons within the PVN, where

they enhance the ACTH-releasing effects of CRH [63]. IL-1

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

HPA axis regulates the inflammatory response. CHD leads to an

inflammatory response, thus IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-

Recent study has shown that increased concentrations of the inflammatory

cytokine IL-6 were associated with disturbances in the HPA axis, as evidenced by

elevated cortisol in depressed patients [67]; activation of the HPA system by

TNF-

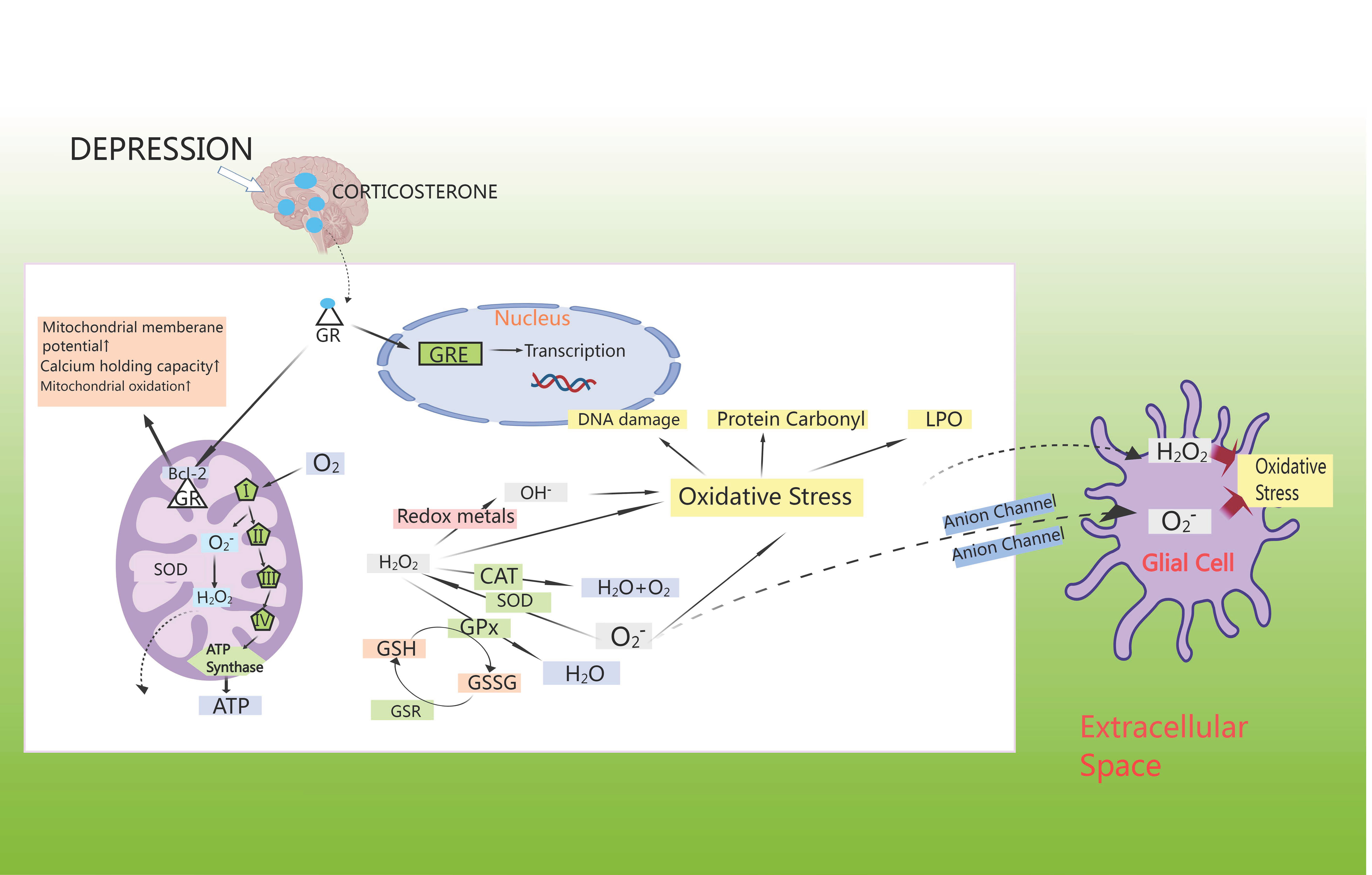

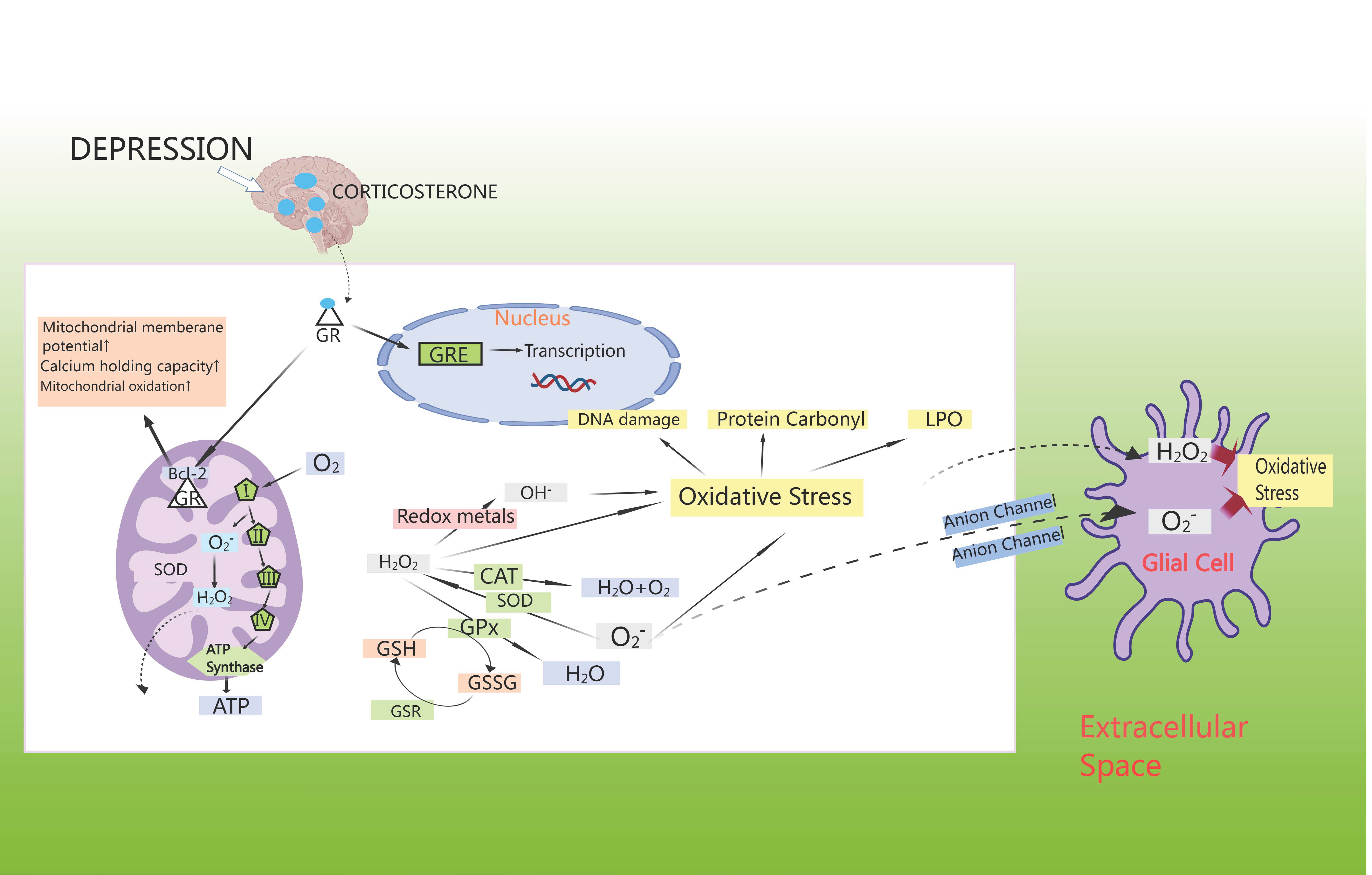

Anxiety disorders show a strong correlation with oxidative stress, which could independently predict cardiovascular events. Oxidative stress damage caused by CHD may contribute to myocardial injury, leading to an excess of reactive oxygen components, altering neuronal signaling and regulating neurotransmitters, thereby contributing to the development of anxiety disorders. Study has demonstrated that oxidative stress could lead to disruption of neurotransmitters such as 5-HT and dopamine, decreasing the activity of antioxidant enzymes in the brain and promoting the release of neuroinflammatory factors in the brain, thus inducing anxiety disorders [75]. Studies has shown that CHD comorbid with anxiety or depression was mainly associated with oxidative stress markers such as malondialdehyde (MDA), glutathione (GSH), glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4), and superoxide dismutase (SOD) [76]. Surprisingly, anxiety/depression leads to an increase in CORT, which activates cytoplasmic GR [77]. These move into the cell nucleus to control the transcription of genes through GC response elements (GREs), where they interact with anti-apoptotic B-cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2) proteins, leading to an increase in mitochondrial membrane potential, calcium retention capacity, and mitochondrial oxidation [78]. Apart from complexes I and III of the electron-transport chain, cellular metabolic activity promotes ATP synthesis by spontaneously generating superoxide, which is then disproportionally converted by superoxide dismutase (SOD) to H2O2, which further transforms into OH– or is reduced to water via the mitochondrial antioxidant pathway [79]. In cytoplasmic extracts, superoxide production arises from nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidation by NADPH oxidase [80]. When neutralized by catalase (CAT) or GPX, H2O2 oxidizes GSH to glutathione disulfide (GSSG) [81]. In turn, the GSH enzyme system facilitates the regeneration of GSH from GSSG, and also engages with superoxide radicals or transition metals like Fe2+ or Cu2+, leading to oxidative harm, protein carbonyl formation, and lipid peroxidation (LPO) in cell membranes [82]. Generally, this H2O2 moves freely from mitochondria to cytoplasmic compartments; superoxide radicals can also diffuse through membrane-bound anion channels to induce oxidative stress in neighboring cells [83] (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

HPA axis induces oxidative stress. GSH enzyme system facilitates the regeneration of GSH from glutathione disulfide (GSSG), and also engages with superoxide radicals and/or transition metals like Fe2+ or Cu2+, leading to oxidative harm, protein carbonyl formation, and lipid peroxidation in cell membranes. GSR, glutathione reductase; LPO, lipid peroxidation; GRE, glucocorticoid receptor element; Bcl-2, B-cell lymphoma-2.

Colaianna et al. [84] discovered that anxiety and depression caused an

early rise in NADPH oxidase 2 (NOX2) expression and oxidative stress within the

hypothalamus, which led to HPA axis function (CRF and ACTH) as well as a shift in

exploratory behavior [84]. Elevated oxidative stress (at a later time) by

long-term elevations in levels of NOX2expression, as well as the adrenal

glands, might determine alterations in peripheral biomarkers (plasma and salivary

CORT) of the HPA axis [85]. Song et al. [86] discovered that exposure to

CORT led to an increase in the levels of inflammatory factors and the lipid

peroxidation product malondialdehyde, while also reducing the levels of

antioxidants in the hippocampus and frontal cortex of mice. Tulipate demonstrated

positive effects on depressive-like behaviors induced by CORT administration in

mice, potentially through the inhibition of HPA axis hyperactivity and oxidative

damage [86]. H2 has been found to reduce inflammation in CHD by modulating

multiple pathways (including the nuclear factor-

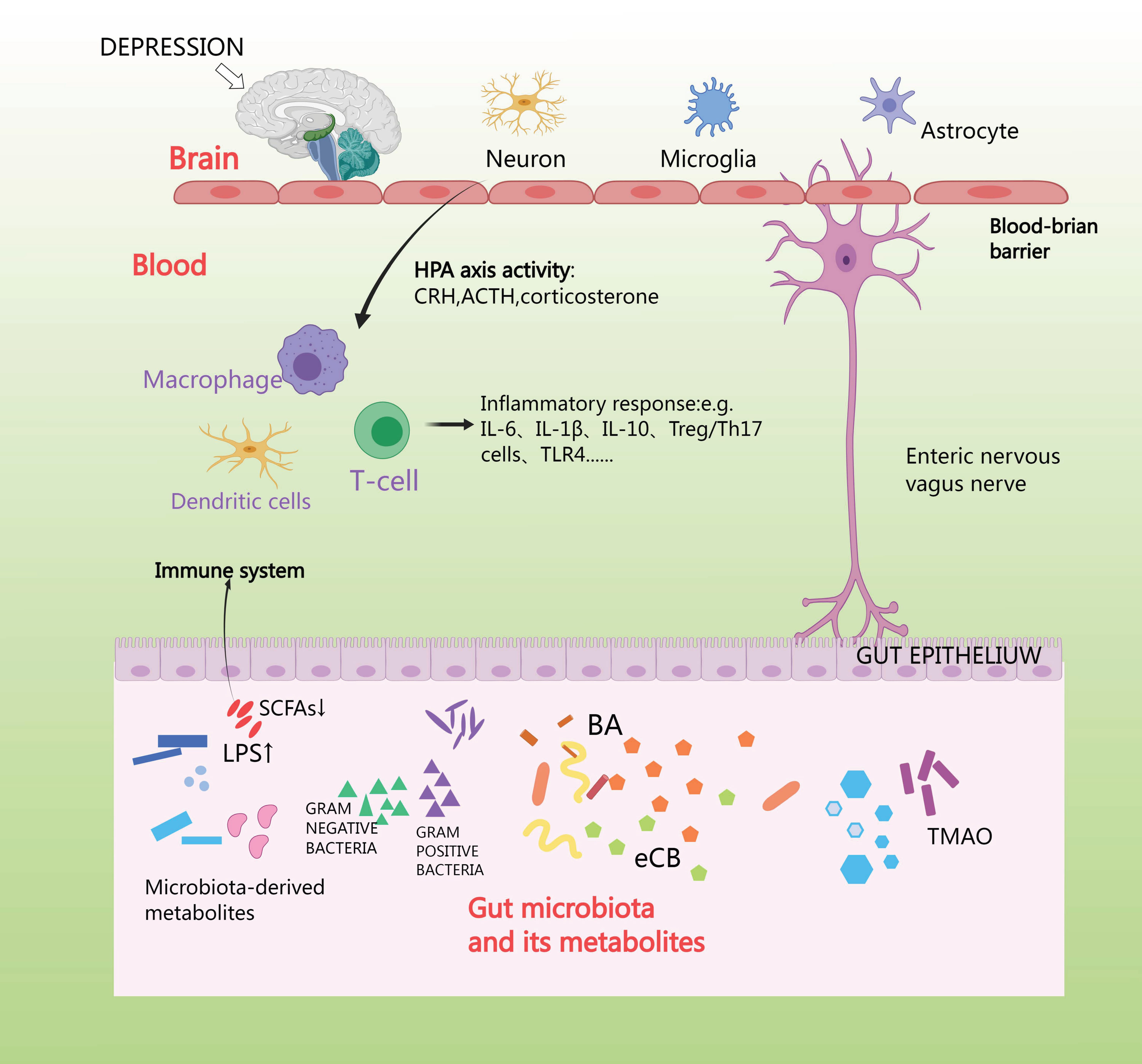

Anxiety depression stimulates the vagus nerve and spinal afferent fibers, which sends signals to the brain, and, in turn, uses efferent sympathetic and parasympathetic fibers to send signals to the intestines, where the adrenal cortex releases cortisol. Cortisol travels through the circulation to reach the target tissues, where the cortisol receptor is expressed on a wide variety of cells in the intestines [90]. First, cortisol affects the brain through its interaction with GRs situated in various regions of the brain, such as the hippocampus, amygdala, and prefrontal cortex [91]. Second, the HPA axis can also induce the release of lipopolysaccharides (LPS) and peptidoglycan [92]. The vagus nerve and the enteric-nervous-system pathways can facilitate swift neural communication, and so neurotransmitters are produced by microorganisms [93]. Generally, microorganisms possess the ability to generate or modify metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFA), bile acids (BA), and endocannabinoids (eCB) [94]. SCFAs produce and release peripheral neurotransmitters such as acetylcholine and 5-HT via enterochromaffin cells, and NE via activation of sympathetic neurons, which is secreted from dietary tryptophan by enterochromaffin cells (EC) located in the gastrointestinal tract (GIT). This activates afferent receptors on nerve fibers; 5-HT is secreted by EC in the intestinal lumen, mucosa, and circulating platelets [95]. Imbalance in gut microbiota can over activate the HPA axis and neuroimmune system and alter neurotransmitter levels, leading to inflammation, increased oxidative stress, abnormal mitochondrial function, and neuronal death [96]. The aim of future studies might be to interfere with this connection using appropriate gut microbial antibiotics, hormones, or receptor antagonists, to further unravel the mechanisms of microbial function in the HPA axis [97] (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

HPA axis affects intestinal flora. Short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) produce and release peripheral neurotransmitters such as acetylcholine and 5-Hydroxytriptamine (5-HT) via enterochromaffin cells, and norepinephrine (NE) via activation of sympathetic neurons, which is made from dietary tryptophan by enterochromaffin cells located in the gastrointestinal tract (GIT). TLR4, toll-like receptor 4; TMAO, trimethylamine N-oxide.

Multiple studies have suggested that consuming probiotics contained

lactobacillus and bifidobacterium might have a positive impact on alleviating

stress-induced HPA axis dysfunction and improving symptoms of depression and

anxiety [98]. Liu et al. [99] showed that Lactobacillus plantarum

JYLP-326 up-regulated p-TPH2, tryptophan hydroxylase 2 (TPH2), and 5-HT1A

receptors (5-HT1AR), while down-regulating the expression of pro-inflammatory

cytokines IL-1

Anxiety can disrupt the homeostatic balance of the endothelial environment by

affecting the sympathetic nervous system and renin-angiotensin system, leading to

a reduction in the physiological function of endothelial cells, then endothelial

damage, which affects arterial diastole and a produces a decrease in sympathetic

activity. This process can lead to CHD [107]. Research has revealed that

individuals suffering from CHD and anxiety or depression exhibit notably reduced

NO levels and elevated ET-1 levels, leading to release imbalance and vascular

endothelial cell damage [108]. This in turn exacerbates the atherosclerotic

process in CHD [109]. Anxiety-like behavior upregulates platelet glycoprotein

receptor expression and enhances platelet aggregation [110]. Feelings of anxiety

are detected in the cerebral cortex, which then sends activation signals through

the hypothalamus to preganglionic sympathetic neurons located in the spinal cord.

Then, those neurons stimulate chromaffin cells in the adrenal medulla, which

leads to the release of NE into the bloodstream [111]. By activating

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

HPA axis increases platelet activation. Increased intracellular

calcium triggers the degranulation of

Noordam et al. [119] observed a rise in the levels of platelet-adhesion-receptor-glycoprotein (GPIb) expression, though selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) reduce platelet activation in depressed patients, demonstrating that individuals suffering from both depression and CHD exhibited enhanced platelet function after treatment with SSRIs. Reduced platelet activation and aggregation in in vitro experiments reduces myocardial infarction (MI) risk [119]. The STRESS-AMI study reported that the primary effect of elevated NE levels was to stimulate platelet activity, thereby promoting coronary-artery occlusion. Combined with evidence of thrombosis in acute coronary events, these findings suggested that NE is a platelet agonist of considerable clinical significance [120]. Higher levels of NE further promote clot formation by enhancing platelet activity [121].

Research has revealed that anxiety can disrupt the homeostatic balance of the endothelial environment by affecting the sympathetic nervous system, parasympathetic nervous system, renin-angiotensin system, and other related systems [122], so that the physiological function of the endothelial cells decreases, and endothelial damage occurs that affects arterial diastole and the reduction of sympathetic activity, thus leading to MACE [123].

The correlation between depression or anxiety and calcitonin-mediated platelet hyperactivation in CHD was investigated in cross-sectional studies. Results showed significantly higher platelet reactivity in patients with depression and anxiety than in those without depression and anxiety. Flow cytometry studies of in vivo platelet activation confirmed that patients with depression had higher than normal levels of platelet activation than did controls [124]. Interestingly, Marlene S’ team examined the platelet 5-HT signaling in a group of individuals with both CHD and depression. They found that depressed patients who experienced minor adverse cardiac events showed an elevated platelet response to 5-HT [125]. A connection between patients with cardiovascular conditions and an increased occurrence of minor adverse cardiac events may suggest that platelets have a specific susceptibility to 5-HT [126]. Research conducted by Lozano et al. [127] on human and mouse platelets revealed that duloxetine, in a dose-dependent manner, inhibited agonist-induced platelet aggregation when compared to the solvent control. It is worth noting that the findings from research on platelet function in individuals with depression are not definitive and indicate the need for more extensive investigations.

There seems to be a range of approaches for individuals with CHD and depression, such as stress reduction techniques, one-on-one or group therapy, and supportive medication options [128]. At present, available clinical interventions for depression and CHD include pharmaceuticals, psychological therapies, physical activity programs, and acupuncture. Western medical therapy to address depression or anxiety in patients with CHD is mainly based on a combination of anxiolytic drugs such as flupirtine or melittin, selective 5-HT reuptake inhibitors (sertraline hydrochloride, paroxetine, fluoxetine, etc.), and benzodiazepines (lorazepam, alprazolam tablets, etc.) and cardiovascular-system protective drugs. SSRIs are the antidepressants of choice because of their anti-inflammatory, antiplatelet aggregation, and HPA-axis-activity-lowering effects [129]. These selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors elevate the levels of 5-HT in the synaptic cleft, effectively suppressing depression-induced CHD with minimal impact on the cardiovascular system. Studies have suggested a potential psychological influence on behaviors associated with statins, which are inhibitors of cholesterol synthesis [130]. Tailored exercise therapies designed to match the specific cardiac function and exercise tolerance of individuals may also contribute to decreasing depression and symptoms related to CHD [131], which have been shown to regulate inflammatory factors and the parasympathetic nervous system, effectively reducing morbidity and mortality in patients with co-existing health conditions [132]. Promoting modifications in lifestyle can additionally bolster this strategy, so patients with CHD and comorbid depression should be actively treated with a combination of medications, psychological interventions, and exercise therapy [133] (Table 1, Ref. [134, 135, 136, 137, 138, 139, 140, 141, 142, 143]).

| Class | Examples | Mechanisms of action | Reference |

| CRH antagonists | N | It is possible that these antagonists would interrupt the positive feedback loop between the amygdala, hypothalamus, and the blueprint-norepinephrine system in the brain, and that CRH-R1 antagonists significantly reduce CRH levels in cerebrospinal fluid | [134] |

| Glucocorticoid receptors (GR) | Mifepristone | Specific glucocorticoid (GC) receptor antagonists partially or completely inhibit (antagonize) GR agonist binding and decrease the activity of GC-enhanced CRH in neurons situated in the central nucleus of the amygdala and areas outside of the neuroendocrine hypothalamus | [135] |

| N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) antagonists | Amantadine | Reduction of stress-induced atrophy in hippocampal neurons. Compounds modulating glutamatergic neurotransmission via mGluR produce antidepressant-like activity in several tests and models in rodents | [136] |

| Ketamine | |||

| Transdermal monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) | Selegiline patch | Inhibition of mucosal monoamine oxidase (MAO) isoenzymes permits selective targeting of brain MAO to produce antidepressant activity | [137] |

| DOV 216,303 | |||

| Substance P antagonists | MK-869 | Blockade of angiogenic-factor activity at the receptor level to inhibit vascularization results in persistently high plasma levels of the parent compound, along with reduced metabolite formation | [138] |

| L-759274 | |||

| CP-122721 | |||

| GR antagonists | Dexamethasone | Inhibition of peripheral pituitary-adrenal activity produces a central hypocorticotropic state | [139] |

| Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) | N | Modulation of multiple neurotransmitter systems as well as modulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, reversal of stress-induced increase in GC receptor expression, inhibition of stress-activated protein kinase type 3 translocation by DHEA treatment, antistress activity; enhancement of neuronal survival and differentiation, neuroprotective effects against oxidative stress, and neurogenic and neurotrophic activity | [140, 141] |

| Selective modulators of GR actions | C108297 | Enhances GR-dependent memory consolidation of inhibitory avoidance task training by inhibiting CRH gene expression showing partial agonistic activity. Opposes the decrease in hippocampal neurogenesis mediated by GR after prolonged exposure to corticosterone (CORT). There is potential for specifically reducing harmful GR-dependent processes in the brain while maintaining the positive aspects of GR signaling | [142] |

| FKBP prolyl isomerase 5 (FKBP5) antagonists | N | Variations in single nucleotides are linked to heightened levels of intracellular FKBP 5 protein, leading to adjustments in GC receptors that control the HPA axis. The K 506 binding protein 51/FKBP 51 plays a role in regulating GR and HPA axis responsiveness, as well as participating in significant gene-environment interactions. | [143] |

The above findings confirmed the role of anxiolytic drugs in the treatment of CHD combined with anxiety therapy, yet mostly focused on studies related to the improvement of patients’ anxiety symptoms; the evidence from studies related to the improvement of patients’ cardiac function was still insufficient. In addition, the results of the present review also corroborated the fact that the drugs for the protection of the cardiovascular system do not have a significant effect on the improvement of patients’ psychological symptoms. As for the effects of antidepressant therapy on CHD, animal experiments have yielded conflicting conclusions and further research is needed; the effects of antidepressant treatment on CHD are not yet fully understood. The management of patients with comorbid depression and CHD lacks definitive treatment guidelines, presenting a challenge for clinicians, so further research is necessary. Efforts should be directed towards improving clinical management and delivering comprehensive care for individuals affected by this dual diagnosis.

This review article examined the link between the HPA axis and anxiety or depression in individuals with CHD. Patients may undergo vasculitis and oxidative stress, which can result in a decrease in the production and release of specific substances within the body, ultimately leading to anxiety or depression. Evidently, the HPA axis plays a significant role in the onset of anxiety or depression, which affects cardiovascular health by regulating endothelial cell function and angiogenesis. Additionally, in the nervous system, it promotes the growth and survival of nerve cells and enhances adrenal GC, ACTH, and AVP production [144]. Based on the above findings from previous studies, we can conclude that a pro-inflammatory state is associated with stress, and HPA-axis dysfunction is responsible for platelet changes leading to a hyperreactive state in depressed patients [145]. Depression is activated, which increases cortisol synthesis and release, resulting in an increase of enterococci and a significant reduction in gut microbiota diversity. This may exacerbate the intestinal inflammatory response, resulting in anxiety and depression [146]. Excess cortisol leads to leaky gut syndrome by modulating the gut barrier function and the inflammatory response [147]. In terms of clinical applications, studies of the HPA axis in CHD combined with anxiety or depression have been dominated by SSRIs, and no specific drug has been developed to target the HPA axis for treatment.

HPA axis activity is a potential biomarker for the treatment of CHD combined with anxiety or depression; it can act on multiple pathways throughout in the organism. It is worth mentioning that the use of therapeutic methods such as administration of CRH or GR antagonists, and other enhancers, can significantly improve patients’ anxiety or depressive symptoms, but are currently only in the research stage in regard to diseases related to central nervous system injuries (e.g., hypertension, stroke, and spinal cord injury) and degenerative neurological diseases (e.g., Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease) [148], and have not yet been widely used in cardiovascular diseases [149]. Our current research is primarily focused on investigating the involvement of the HPA axis in the development of comorbid CHD and anxiety or depression, with a potential aim to use its activity as a biomarker for clinical treatment.

CHD, when combined with anxiety or depression, presents a complex combination of cardiovascular abnormalities and psychological issues. This mutual relationship between the two conditions creates difficulties in treatment, but technological advancements offer significant potential for improvement. Above all, the HPA axis plays a multifaceted role, making it challenging to ascertain whether its excessive activity is a consequence or a trigger of the illness. Subsequent research will contribute to unraveling the involvement of the HPA axis in depression and schizophrenia, as well as advancing novel approaches for drug intervention.

ACTH, corticotropin hormones; AVP, Arginine-vasopressin; Ang II, Angiotensin II; BST, Bone marrow stromal cell antigen; BDNF, Brain-derived neurotrophic factor; CSF, Cerebrospinal fluid; CHD, Coronary atherosclerotic heart disease; CRH, Corticotrophin-releasing Hormone; CRF, Corticotropic releasing factor; CRP, C-reactionprotein; CRF1R and CRF2R, Corticotropin-releasing factor type 1 and 2 receptors; CORT, Corticosterone; CAT, catalyst; cAMP, Cyclic Adenosine Monophosphate; ET-1, Endothelin-1; EC, Enterochromaffin; FKBP 51, FK506-binding protein 51; GR, Glucocorticoid Receptors; GC, Glucocorticoid; GPX, Glutathione peroxidase; GSH, Glutathione; GSSG, Glutathione disulfide; GIT, Gastrointestinal tract; GABA, Gamma-aminobutyric acid; GPIb, Glycoprotein Ib; HPA, Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal; ICAM-1, Intercellular adhesion molecule 1; IL-1, Interleukin-1; LPO, Lipid peroxidation; LPS, Lipopolysaccharide; MAPK, Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase; MACE, Major cardiovascular adverse events; NADPH, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate; NE, Norepinephrine; NF-

LSF: Conceptualization, Data curation collected studies. YMW: Writing-original draft, Conceptualization, Data curation. HL: Providing photo production and layout. BN: Collected studies of Chinese herbs and improved article language. HBY: Providing data management for this article. SLL: Literature search. YTW: Conceptualization, Data curation collected studies. MJZ and JM: designed the literature retrieval strategy, reviewed the manuscript, and obtained funding. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

We express our gratitude to all those, excluding the authors, who helped during the writing of this manuscript.

Shaanxi province key R & D plan-key industry innovation chain (group) project (2024SF-ZDCYL-03-21); The construction project of Shaanxi Provincial Academician Workstation-Wu Yiling Academician Workstation (Shaanxi Group Tongzi [2019] No.49-30); Shaanxi Provincial Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine Research Project of Traditional Chinese Medicine (SZY-KJCYC-2023-009).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.