1 Department of Biomedical and Biotechnological Sciences, Section of Anatomy, Histology and Movement Science, School of Medicine, University of Catania, 95123 Catania, Italy

2 Department of General and Emergency Surgery, Garibaldi Hospital, 95124 Catania, Italy

Abstract

A growing body of research highlights the positive impact of regular physical activity on improving physical and mental health. On the other hand, physical inactivity is one of the leading risk factors for noncommunicable diseases and death worldwide. Exercise profoundly impacts various body districts, including the central nervous system. Here, overwhelming evidence exists that physical exercise affects neurons and glial cells, by promoting their interaction. Physical exercise directly acts on ependymal cells by promoting their proliferation and activation, maintaing brain homeostasis in healthy animals and promote locomotor recovery after spinal cord injury. This review aims to describe the main anatomical characteristics and functions of ependymal cells and provide an overview of the effects of different types of physical exercise on glial cells, focusing on the ependymal cells.

Keywords

- exercise

- physical activity

- glial cells

- ependymal cells

- neuroanatomy

Mounting evidence over the years has investigated the role exerted by regular

physical activity on physical, mental, and emotional well-being [1]. Physical

exercise affects all systems of the human body, including the central nervous

system (CNS) thus improving cognitive functions, such as learning and memory, and

general mental health, by reducing stress and anxiety [2, 3]. Studies in animal

models have shown how regular physical activity increased the volume of certain

brain areas such as the hippocampus, involved in memory, learning, and emotions,

and in the prefrontal and temporal lobes, involved in several functions such as

executive functions and language comprehension [4, 5]. Recently, it has been

demonstrated that rats performing moderate physical activity significantly

increased in the hippocampal dentate gyrus (DG) and cerebellum the expression

levels of Activity-Dependent Neuroprotective Protein (ADNP), essential for proper

brain functions, and

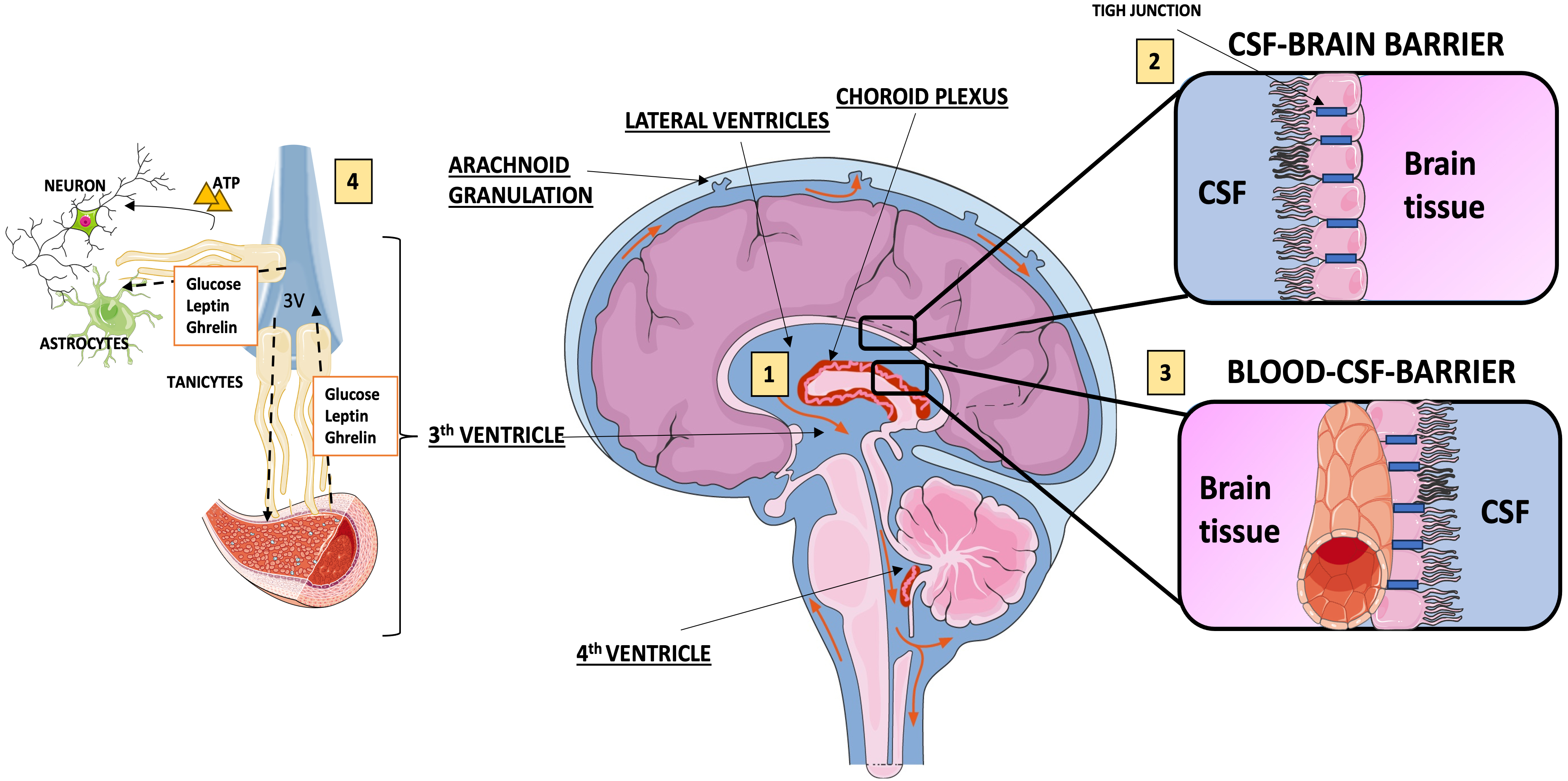

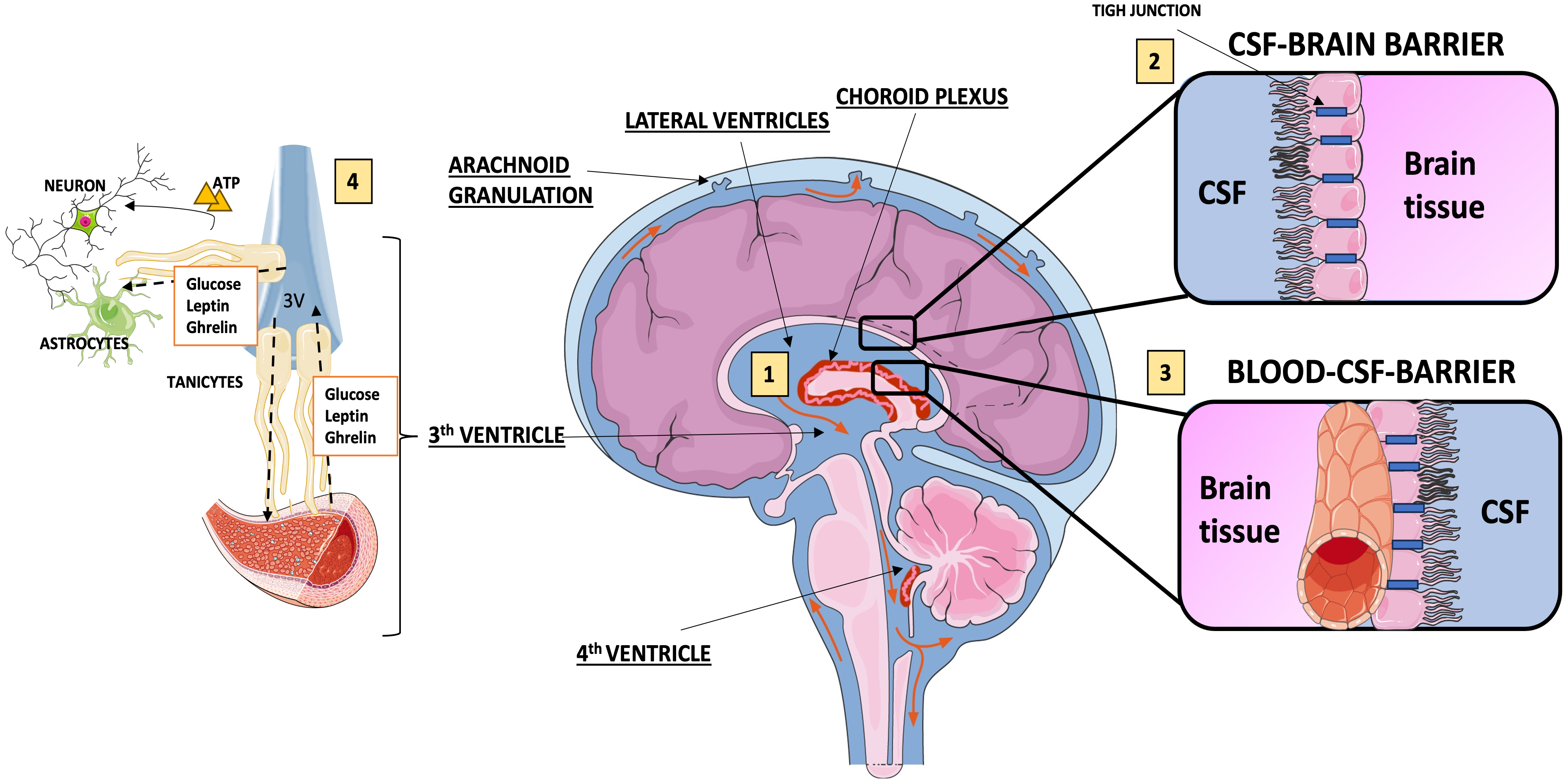

The exercise-induced neuroprotective effects are also due to the direct effects played on glial cells, including ependymal cells which form the lining of the ventricular system and the central canal of the adult spinal cord (SC) and play a key roles in the CNS for maintaining brain homeostasis [21].

1. They form the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)-brain barrier and are components of blood–barrier [22, 23].

2. They are responsible for the production of CSF, by regulating the concentrations of active peptides in the CSF and extracellular space of the brain.

3. They regulate the fluid dynamics of CSF [24, 25] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Functions of ependymal cells. (1) Ependymal cells prompt the transport of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from the lateral ventricle to the third and fourth ventricles, where through the foramen of Magendie and Luschka, the CSF flows into the subarachnoid spaces, to be finally absorbed mostly at the arachnoid granulations in the superior sagittal venous sinus; (2) ependymal cells lining the lateral ventricles allow relatively free diffusion of solutes between brain interstitial fluid and cerebrospinal fluid; (3) the blood-CSF-brain barrier is formed by tight junctions of ependymal cells of the choroid plexus; (4) tanycytes interact with astrocytes and blood vessels promoting the exchange of substances among CSF, brain interstitial fluid and blood. Fig. 1 was produced with the support of “Servier Medical Art” by Servier (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

In this mini-review, we describe the main anatomical properties and functions characterizing the ependymal cells in the healthy brain, and the influence of different types of physical exercise on glial cells, focusing on the ependymal cells whose changes might improve brain health.

Ependymal cells, essential components of the CNS, are ciliated-epithelial glial cells derived from radial glial cells [26], whose transcriptomic census was deeply characterized [27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32]. The main characteristics of ependymal cells are summarized in Table 1 (Ref. [33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44]). Ependymal cells realize a continuous monolayer that lines the inner surfaces of the aqueduct, the cerebral ventricles, and the central canal of the SC [45].

| Authors | Ependymal cell types | Mainly localization | Functions |

| Classification based on cilia numbers and locations in brain regions | |||

| Sawamoto K et al. [35] | E1 | Lateral, third and fourth cerebral ventricles | Regulating the unidirectional flow of cerebrospinal fluid |

| Mirzadeh Z et al. [34] | E2 | Spinal canal and part of the third and fourth ventricles and cerebral aqueduct | Detection of CSF composition and transmission of extracellular signals |

| Mirzadeh Z et al. [33]; Alfaro-Cervello et al. [36] | E3 | Preoptic and infundibular recesses of the third ventricle, spinal canal | Detect changes in CSF composition |

| Classification based on morphologies | |||

| Mullier A et al. [38]; Pasquettaz R et al. [39]; Dali R et al. [40]; Akmayev IG et al. [41]; Rodríguez EM et al. [42]; Yoo S et al. [43]; Müller-Fielitz H et al. [44]; Mirzadeh Z et al. [33] | Tanycyctes | Transporting hormones and other signaling molecules between the CSF and the brain | |

| Meletis K et al. [37] | Cuboidal | Lateral, third and fourth cerebral ventricles, spinal canal | Regulating the unidirectional flow of cerebrospinal fluid |

| Meletis K et al. [37] | Radial | Dorsal or ventral pole of the ependymal layer, with a basal process oriented along the dorsoventral axis | Give rise to mature ependymal cells |

The table shows the ependymal cell classifications, locations, and function. CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; E1, multiciliated ependymal; E2, ciliated ependymal; E3, uniciliated ependymal.

Studies classifying ependymal cells based on different cilia numbers and locations in specific brain regions identified: multiciliated ependymal cells (E1 cells), ciliated ependymal cells (E2 cells), and uniciliated ependymal cells (E3 cells) [21, 33, 34]. E1 cells, representing the most common subtype, they are characterized by several cilia on their apical surface and are localized in the lateral, third, and fourth ventricles, where they play a key role in regulating the unidirectional flow of CSF [35]. E2 cells consist of both primary and motile cilia and are bi-ciliated [34], they are localized in specific regions of the third and fourth ventricles as well as the spinal canal, and they are involved in the detection of CSF composition and transmission of extracellular signals [34]. E3 cells are mainly localized in a small region of the third ventricle within the hypothalamic area, lack cilia and have a single primary cilium [33]. Moreover, these cells are also found around the central canal in young adult mice (2–3 months old) [36]. These cells detect changes in CSF composition, including metabolite levels.

Based on the different morphologies, ependymal cells can be also classified into cuboidal ependymal cells, radial ependymal cells, and tanycytes [37]. The first ones have a cube-shaped appearance and belong to multiciliated ependymal cells [37]. Radial ependymal cells have a cylindrical or columnar shape with one to three types of cilia and a long basal process [37]. Radial glial cells were found in the ventral and dorsal poles of the neonatal rat spinal cord [46]. Following injury, these cells through connexin signaling, improve the response of the central canal stem cell niche to repair [47].

Tanycyctes are uniciliated ependymal cells mainly localized in the walls and

floor of the third ventricle [38, 39]. They possess long basal process extending

through the hypothalamic parenchyma contacting blood vessels and different neuron

types, such as orexigenic and anorexigenic neurons involved in the control of

energy balance [40]. Tanycytes based on an older classification were classified

into:

Ependymal cells are essential for the proper functioning of the central nervous system. Alterations in generation, maturation, and integrity of ependymal cells trigger early onset fetal hydrocephalus through aqueductal stenosis [48]. The production of CSF occurs by specialized populations of ependymal cells within the choroid plexus forming the blood-CSF barrier [49]. The ependymal cells of the choroid plexus contain on the apical surface ionic pumps (e.g., Na+–K+ ATPase) through which they produce the chemiosmotic energy for the osmotic gradient that allows fluid formation by the cells of the choroid plexus [50]. In addition, ependymal cells are involved in the regulation of cerebrospinal fluid flow. Indeed, alterations in the polarity of planar ependymal cells (PCPs) result in aberrant cerebrospinal fluid circulation. Cerebrospinal fluid flow initiated in the lateral ventricle (LV), maintains cerebrospinal fluid homeostasis and drives neuroblast migration and neurogenesis [51, 52]. Interestingly, in the adult ventricular-subventricular zone, ependymal cells act as a source of niche factors modulating neural stem cell (NSC) function thanks to their close contact with B1 cells [53], a subtype of astroglial cells that retain NSC properties [54].

Several studies carried out in rodents and humans reveal that physical exercise can induce a profound impact in brain homeostasis and intellectual functions. Moreover, the positive effect of physical exercise on neurodegenerative diseases is a current topic [55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60]. It has already been shown how exercise programs administered to individuals with neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s [55] and multiple sclerosis [56, 57, 58, 59], could be useful in the management of motor symptoms and functional motor ability, to perform tasks of daily living. However, the mechanisms of action behind improving CNS health and function and the most effective exercise protocol are not completely understood.

One of the possible mechanisms of action through which exercise positively affects the nervous system is through the effect on glial cells [60]. However, there is no homogeneity in exercise protocols and results. Therefore, in the following section, we will discuss the most recent studies analyzing the effects of different exercise protocols on glial cells health and activity.

Due to the narrative nature of this mini-review, we selected the included articles from a single database (PubMed) by using the following string “exercise AND “glial cells”” and considering the articles published in the last 10 years, to be as objective as possible in the narrative of the section. We found 102 articles published in the last 10 years. From these 102 articles, we selected 33 articles from the title and 18 were included and are summarized in Table 2 (Ref. [61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78]) and discussed in the present section. 15 articles were excluded because they were review articles or the exercise protocol was not detailed or did not present a clear result on glial cells.

| Author | Year | Frequency | Intensity | Time | Type (tools) | Results | Region | Subjects |

| Zhang et al. [74] | 2024 | 4 w | NS | NS | Voluntary endurance (wheel running) | Decreased activation of glial cells due to inflammatory process | Hippocampus | Mice |

| Kiss Bimbova et al. [71] | 2023 | 5 d/w; 6 w | 16.2 m/min; 19.8 m/min; 22.2 m/min; 24.6 m/min; 27.6 m/min (1–6 w) | 40–60 min (Monday to Friday) | Endurance (treadmill) | Positive effect on the oligodendrocyte population after spinal cord injuries | Gene expression; spinal cords | Mice |

| Yamaguchi et al. [73] | 2023 | 15 d | Continuous running exercise (1 w) | NS | Endurance (running wheel) | Modifies the composition of astrocytic population and phenotype | Peri-infarct cortex | Mice |

| High-intensity exercise (1 w) | ||||||||

| Feng et al. [70] | 2023 | 5 d/w; 8 w | 30–40 m/min; 45–50 m/min; 50–55 m/min; 60 m/min; (1–8 w) | 30 min: 10 bouts of 30-s sprint 2.5 min rest | HIIT (treadmill) | Alleviated the over-activation of microglia and astrocyte; regulated astrocyte phenotype and polarization | Cortex; hippocampus | Rats |

| Vitorino et al. [69] | 2022 | 2 d/w; 4 w | 9 m/min | 50 min | Endurance (treadmill) | Influences on astrocytes morphology in Parkinson’s | Striatum | Mice |

| Muraro et al. [77] | 2022 | 3 d/w; 10 w | Load 5% | 30 min | Swimming | Effect on glial cells number in obese rats | Hypotalamo | Rats |

| Rodrigues et al. [78] | 2021 | 3 d/w; 2 w | 30%; 40%; 50%; 60%; 70%; 80% of 1 RM (from day 1 to day 6) | 3 set × 10 reps | Resistance training + protein supplementation | Inhibits spinal microglia negative activation | Spinal cords | Rats |

| 120 sec rest | ||||||||

| Wang et al. [76] | 2020 | 6 d/w; 7 w | NS | 50 min | Swimming + diet control | Suppress the activation of microglia and astrocytes in the inflammation | Hypotalamo | Mice |

| Leardini-Tristão et al. [68] | 2020 | 3 d/w; 12 w | 60% MET | 30 min | Endurance (treadmill) | In cerebral hypoperfusion, early moderate exercise improves astrocyte coverage in blood vessels and decreases microglial activation | Cereblal cortex; hyppocampus | Rats |

| Luo et al. [67] | 2019 | 5 d/w; 6 w | First week 10 m/min to 18 m/min; 2–6 weeks 20 m/min | 20 min | Endurance (treadmill) | Beneficial effects on oligodendrocytes and potential antidepressant effects | Prefrontal cortex | Rats |

| Jang et al. [66] | 2019 | 5 d/w; 12 w | 75%–80% VO2 max | 60 min | Endurance (treadmill) | Reduced IBA1-positive microglial cells | Hippocampus | Mice |

| Piotrowicz et al. [61] | 2019 | NS | 40 w with increments of 40 w every 3 min | To exhaustion | EVE (cycle ergometer) | Increased glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor. EVE activates astrocytes | Blood sample | Healthy Men |

| Naghibzadeh et al. [72] | 2018 | 5 d/w; 4 w | LICT: 70% of MEC HIIT: 2- min 90% 1- min 50% of MEC | NS | HIIT and LICT (treadmill) | Oligodendrocyte and microglia cells increased more in the HIIT group than to LICT | Hippocampus | Mice |

| Kassa et al. [65] | 2017 | 5 d/w; 7w | 20 m/min | 45 min | Endurance (treadmill) | Microglia activation was most marked after physical exercise | Spinal cord | Mice |

| Fahimi et al. [64] | 2017 | 5 d/w; 5 w | 8, 10, 12, 14 m/min from 2–5 w | 20 min each with a 10 min break | Endurance (treadmill and running wheel) | Changed astrocytes morphology, and orientation of projections towards dentate granule cells | Hippocampus | Mice |

| Leite et al. [75] | 2016 | Every day; 4 w | 1% body weight | 20 min | Swimming | Decreased activation of astrocytes and microglia | Hypothalamus | Rats |

| Lovatel et al. [63] | 2014 | Every day; 2w | 60% VO2 max | 20 min | Endurance (treadmill) | Exercise attenuates the ischemia-induced effect on microglia and increase the % area occupied by astrocytes | Hippocampus | Rats |

| Lee et al. [62] | 2014 | Twice a day; 6 d/w; 5 w | 10.5 m/min | 15 min | Endurance (treadmill) + melatonin | Effect on behavioral recovery associated with a neural stem cell population capable of differentiating into oligodendrocytes, astrocytes after spinal cord injury | Spinal cords | Rats |

The table shows the characteristics of the exercise protocol, the effect, and the subjects analyzed. d/w, day per week; d, day; w, weeks; NS, not specified; MET, metabolic equivalent; HIIT, high-intensity interval training LICT, versus low-intensity continuous training; EVE, exercise test to volitional exhaustion; MEC, maximal exercise capacity; RM, repetition maximum; VO2 max, maximal oxygen consumption; IBA1, ionized calcium binding adaptor; min, minutes; sec, seconds.

An initial overview of the studies included shows that over the past 10 years, the relationship between exercise and glial cell health has been investigated almost exclusively in animals (rats and mice) [62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78]. Only one study, among the 18 included, considers the effect of exercise on glial cells effect of exercise on humans. In detail, Piotrowicz et al. [61] show that an exercise test for volitional exhaustion (EVE), performed by cycle ergometer, increases blood concentrations of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) and thus that exhaustion exercise can activate astrocytes. The cycle ergometer test was performed at an initial intensity 40 watts, that was increased by 40 watts every 3 minutes until exhaustion. However, they detected the GDNF in the blood so they used an indirect method for assessing the health of glial cells, by administering the exercise only once. Thus, we do not know any long-term effects of EVE.

Considering the other 17 studies (on animals) the regions of the nervous system considered were the hippocampus, hypothalamus, spinal cords, striatum, and cortex. Most studies in the literature over the past 10 years investigate the effect of aerobic-type training predominantly using treadmill [62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72] running wheels [64, 73, 74], or swimming exercise [75, 76, 77]. For example, Vitorino et al. [69] showed that 4 weeks of endurance exercise induces morphological changes to astrocytic processes in the striatum: it increases the distal-proximal distance and the number of astrocytic processes.

Only one study [78] showed that resistance training, along with protein supplementation, can inhibit spinal microglia activation. The activation of microglia is a hallmark of nervous system pathology. Indeed, Rodrigues et al. [78] protocol included 3 days per week of training for 2 weeks with a gradual increase of the load from 30% to 80% of one-repetition maximum (1-RM) performing 3 sets of 10 repetitions with 120 seconds rest.

Regarding training intensity, the included studies present very heterogeneous protocols: many present an incremental intensity [61, 64, 66, 67, 70, 71, 78] during exercise, others a constant intensity [62, 63, 65, 68, 69, 75, 77], and others an interval intensity (interval training) [70].

One study [73] combines two types of intensities in the same group: the mice performed continuous training for the first week and interval training exercises for the second week, obtaining a change in the composition of the astrocytic population and their phenotype.

In contrast, Naghibzadeh et al. [72] compare two different groups performing continuous and interval training showing that oligodendrocyte and microglia cells increased more after the interval training period than when performing continuous training.

Feng et al. [70] confirmed the same results by investigating the effects of high-intensity interval training (HIIT) on the activation and polarization of microglia and astrocytes showing that HIIT alleviated decreased intersection numbers in the cortex and hippocampus, increased the size of the microglia cell body and alleviated the over-activation of microglia and astrocytes in the cortex and hippocampus of rats. In addition, astrocyte polarization from the pro-inflammatory A1 phenotype to the neuroprotective A2 phenotype was identified after 8 weeks of 30 minutes of HIIT.

The same heterogeneity was also found in the frequency of the protocols and in the duration of individual training sessions. To affect glial cell activity, the exercise frequency ranged from a minimum of two days a week to performing the workouts every day of the week. Instead, the duration of the individual session ranged from 15 to 60 consecutive minutes. However, Lovatel et al. [63] demonstrated how the effect of exercise on glial cell function depends on the timing of administration concerning the disease: post-ischemic exercise attenuates the ischemia-induced effect on microglia but pre-ischemic exercise seems not to alter glial cell staining after ischemia in long-term.

Another important finding from our investigation was that exercise could amplify its effect on glial cells when administered together with specific supplements. It’s demonstrated that swimming exercise with a vitamin D integration in obese rats determined an increase in the number of glial cells in the nucleus of the hippocampus more than single interventions (vitamin D or exercise) administered singly promoting the restoration of the brain nuclei involved in the control of food intake [77]; even Lee et al. [62] indagated the synergistic effect of melatonin and exercise on behavioral recovery associated with a NSC population capable of differentiating into oligodendrocytes, and astrocytes after SC injury.

Accumulating evidence has indicated that the profound impact of physical

exercise on the brain is also due to the effects on glial cells, including

ependymal cells. In particular, Cizkova et al. (2009) [79], studied the

proliferation of the ependymal progenitors in the SC central canal of adult rats

subjected to compression SC injury or enhanced physical activity. The exercise

rats group performed forced running wheel (RW) for 30 minutes daily for 14 days’

survival. Moreover, the rats had free access to RW at any time, especially at

night, when they showed the highest physiological activity. Results showed a

significant immunoreactivity of Bromo-deoxyuridine (BrdU) cells in the thoracic

SC at 4 and 7 days, suggesting an exercise-mediated endogenous ependymal cell

response. Another study [80], investigated the effect of voluntary exercise on

the neurogenesis occurring in the intact SC by analyzing neural progenitor cells

(NPC), which preferentially give rise to oligodendrocytes (OL) and radial glial

cells [81, 82]. The mice performed voluntary running for 7 or 14 days, and the

minimum distance run by each animal was at least 3 km per day. Results showed a

time-dependent increase in nestin, representing the neural stem or progenitor

cell marker, in the ependymal area of active animals as compared to sedentary

mice, suggesting that voluntary exercise induces the generation of NPCs in the

adult intact spinal cord. Another study demonstrated that a single exposure to a

mechanosensory stimulus induces immediate proliferation of progenitor cells in

the spinal dorsal horn inducing neurogenesis [83]. The effect of voluntary

exercise on neurogenesis was also investigated by Niwa et al. [84]. They

used stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats and control rats, sub-divided

into sedentary or active rats, which from 6 weeks after birth, ran voluntarily on

a running wheel. The results showed that voluntary exercise increased the

immunoreactivity of tanycyte markers in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive

rats irrespective of the occurrence of stroke. High co-expression levels of BrdU

and nestin, were found in the hypothalamic subependymal region and third

ventricle before and after the stroke in active rats, suggesting that exercise

promotes the proliferation of tanycytes, which are involved in the regulation of

different physiological functions, ranging from reproduction to energy

balance [85, 86, 87]. Furthermore, the increased co-expression of BrdU with the

differentiation markers of progenitor cells observed in exercising stroke-prone

spontaneously hypertensive rats as compared to the sedentary group confirmed the

positive role of exercise in the differentiation of newborn cells to a neuronal

progenitor cell phenotype. Noteworthy, in the cerebrospinal fluid of exercising

rats, were found high levels of fibroblast growth factor (FGF-2), which plays a

key role in cellular homeostasis within the adult hypothalamus, and is required

to induce the proliferation of

Foret et al. [89] demonstrated that physical exercise increased ependymal cell proliferation while improving locomotor recovery. In particular, they performed their analysis in female rats divided into four experimental groups: control rats, uninjured rats with treadmill training, SC-injured untrained rats, and SC-injured rats with treadmill training. The treadmill training was set for 28 days in three daily sessions of 10 min separated by five min-breaks. The results showed that treadmill training significantly increased nestin immunoreactivity in ependymal cells of both uninjured and injured spinal cords. The authors ascribed these results to the ability of exercise to maintain the stem nature of ependymal cells. Furthermore, they found an increased number of nestin-expressing cells around the central canal associated with better behavioral locomotor scores.

However, more recent studies demonstrated that ependymal cells, which reside in the same niche as NSCs, are transcriptionally distinct from NSCs and don’t behave as NSCs or progenitors in vitro or in vivo [90, 91, 92]. Moreover, it was recently demonstrated that nestin-positive cells are heterogeneous and rarely form ependymal cells after spinal cord injury [92].

Thanks to numerous medical advances, average life years have steadily increased. However, a longer life span is often associated with a higher risk of experiencing disease, disability, and especially cognitive decline. Therefore, adopting a healthy lifestyle and identifying tools that can promote brain health and neurogenesis are needed. Physical activity seems to play a crucial positive role, promoting brain plasticity, neurogenesis, and cognitive functions [6, 93]. Exercise promotes the expression and release of different neurotrophic factors, exerts anti-neuroinflammatory effects, and modulates different intracellular signaling [94, 95, 96]. The potent effect of physical exercise on brain health is mediated by a direct effect on neurons and glial cells. The latter cells play a pivotal role in maintaining brain homeostasis by promoting synaptic connectivity, neuronal excitability, synaptogenesis, and neurogenesis [97]. Exercise can modulate the characteristics of glial cells modifying morphology, and gene expression, increasing their number and the concentration of the glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factors leading to neuroplasticity and neurogenesis. The evidence above described also demonstrated a direct effect of exercise on ependymal cells, in terms of activation and proliferation, leading to better homeostasis and increased locomotor recovery after spinal cord injury that could be useful in the future in structuring neurorehabilitation. However, there is no homogeneity as to which characteristic exercise should be most effective. Future studies should verify the direct and indirect effect of exercise on glial cells in healthy and diseased animals and also in humans to understand the mechanisms of action behind the benefits that physical activity, gives even in conditions affecting the health of the CNS. Prospects should concern the stipulation of exercise protocols that are homogeneous in FITT principle (frequency, intensity, time, and type of exercise) and then create guidelines directed toward that end.

GMus, GMau and AA organized, designed, and wrote the article. GE and VD have contributed to the interpretation of data for the work, they drafted and revised this article for key intellectual content and they were responsible for literature collection and image creation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Thanks to all the peer reviewers for their opinions and suggestions.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest. Alessandra Amato and Giuseppe Musumeci are serving as the Guest editors of this journal. We declare that Alessandra Amato and Giuseppe Musumeci had no involvement in the peer review of this article and has no access to information regarding its peer review. Full responsibility for the editorial process for this article was delegated to Jessica A. Filosa.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.