1 Department of Rehabilitation, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Shandong First Medical University, 271000 Taian, Shandong, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is currently the second most common degenerative neurological disorder globally, with aspiration pneumonia caused by difficulty swallowing being the deadliest complication. The patient’s subjective experience and the safety of swallowing have been the main focus of previous evaluations and treatment plans. The effectiveness of treatment may be attributed to the brain’s ability to adapt and compensate. However, there is a need for more accurate assessment methods for dysphagia and further research on how treatment protocols work.

This systematic review was designed to assess the effectiveness and long-term impact of published treatment options for swallowing disorders in patients with PD.

In adherence to the Preferred Reporting Items for Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines, we conducted a systematic review where we thoroughly searched multiple databases (PubMed, Web of Science, Elsevier, and Wiley) for clinical studies published in various languages until December, 2023. Two reviewers evaluated the studies against strict inclusion/exclusion criteria.

This systematic review included a total of 15 studies, including 523 participants, involving six treatment approaches, including breath training, deep brain stimulation, reduction of upper esophageal sphincter (UES) pressure, transcranial magnetic stimulation, postural compensation, and video-assisted swallowing therapy. Primary outcomes included video fluoroscopic swallowing study (VFSS), fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES), high-resolution pharyngeal impedance manometry (HPRIM), and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI).

Treatments that reduce UES resistance may be an effective way to treat dysphagia in PD patients. HRPIM can quantify pressure changes during the pharyngeal period to identify patients with reduced swallowing function earlier. However, due to the limited number of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) included and the high risk of bias in some studies, large-scale RCTs are needed in the future, and objective indicators such as HRPIM should be used to determine the effectiveness and long-term impact of different therapies on dysphagia in PD patients.

Keywords

- Parkinson’s disease

- dysphagia

- high-resolution pharyngeal impedance manometry

- upper esophageal

Parkinson’s disease (PD), also referred to as tremor paralysis, is the second most prevalent neurodegenerative disorder worldwide, following only Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in terms of prevalence rate [1]. PD is identified by its characteristic motor impairments, such as slow movement, tremors at rest, muscle stiffness, and difficulty maintaining balance [2]. After the loss of around 30% of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc), these symptoms frequently manifest [3]. In addition, a plethora of non-motor symptoms, including dysphagia, salivation, constipation, sensory disturbances, mood disorders, and psycho-cognitive deficits, precede the onset of dyskinesia [4]. In the case of dysphagia, aspiration pneumonia is the most important cause of death. Dysphagia is among the triad of factors leading to aspiration pneumonia, which is the main cause of death [5].

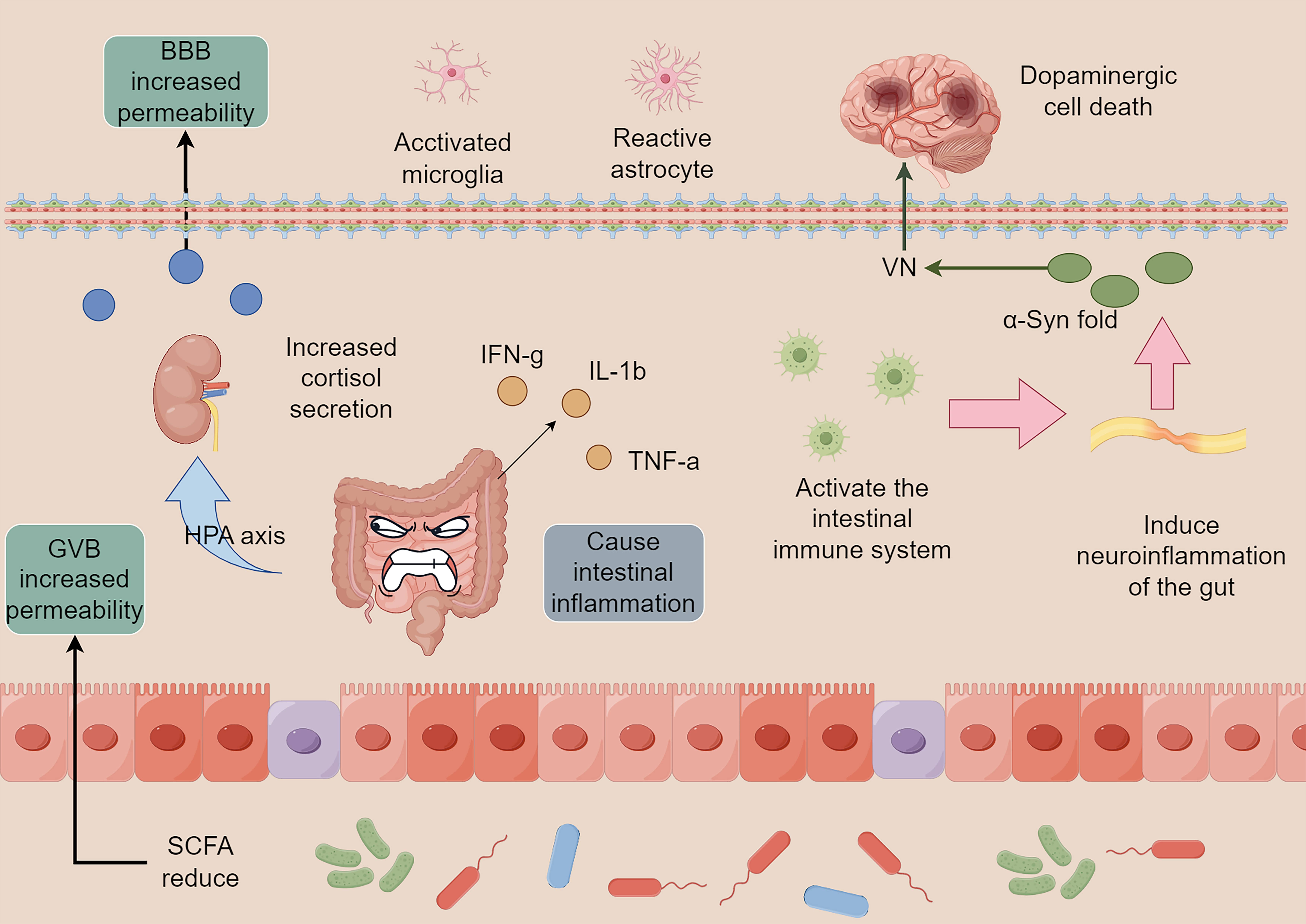

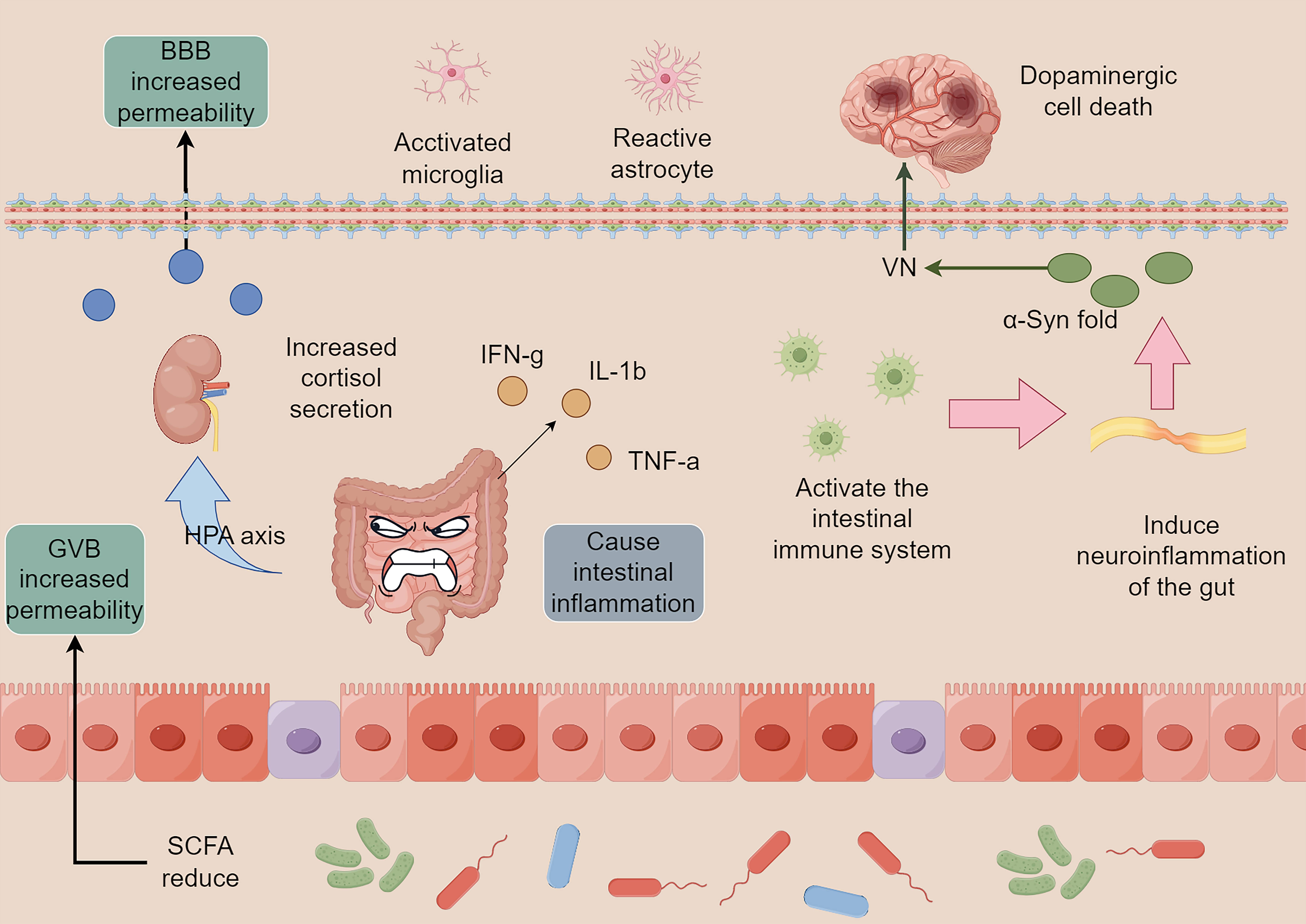

In recent years, research has led to a shift in our comprehension of PD,

transforming it from a singular central nervous system (CNS) ailment to a

condition that can affect various systems within the body. The primary

alterations observed in PD involve the misfolding and abnormal accumulation of

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Intestinal flora imbalance and neuroinflammation. The imbalance

of intestinal flora and infection by foreign pathogens can cause intestinal

inflammation and induce the release of pro-inflammatory factors, including

IFN-g, IL-1

The intestinal tract is the window of communication between the organism and the outside world, and has roles in digestion and providing a physical barrier. With the highest number of immune cells in the body, it consistently ensures stability within the organism. The intestinal flora is essential for the gut to fulfill these roles. Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), metabolites of the intestinal flora, regulate microglia maturation and function [11]. In contrast, microglia are the primary immune cells of the nervous system responsible for eliminating pathogens and diseased cells, thereby contributing to the maintenance of nervous system stability and facilitating remodeling [12]. These factors are essential for preserving the equilibrium of the nervous system and promoting restructuring. Thus, dysregulation of the gut flora and alterations in its metabolites are the main factors that induce neuroinflammation and endocrine disruption, leading to ENS dysfunction. These disturbances then proceed along the GBA to reach the CNS, where PD eventually occurs. It has also been reported that Helicobacter pylori infection can affect the absorption of levodopa, which triggers motor fluctuations in patients with PD [13]. Therefore, stabilizing the intestinal flora is the basis for preventing and delaying the progression of the disease.

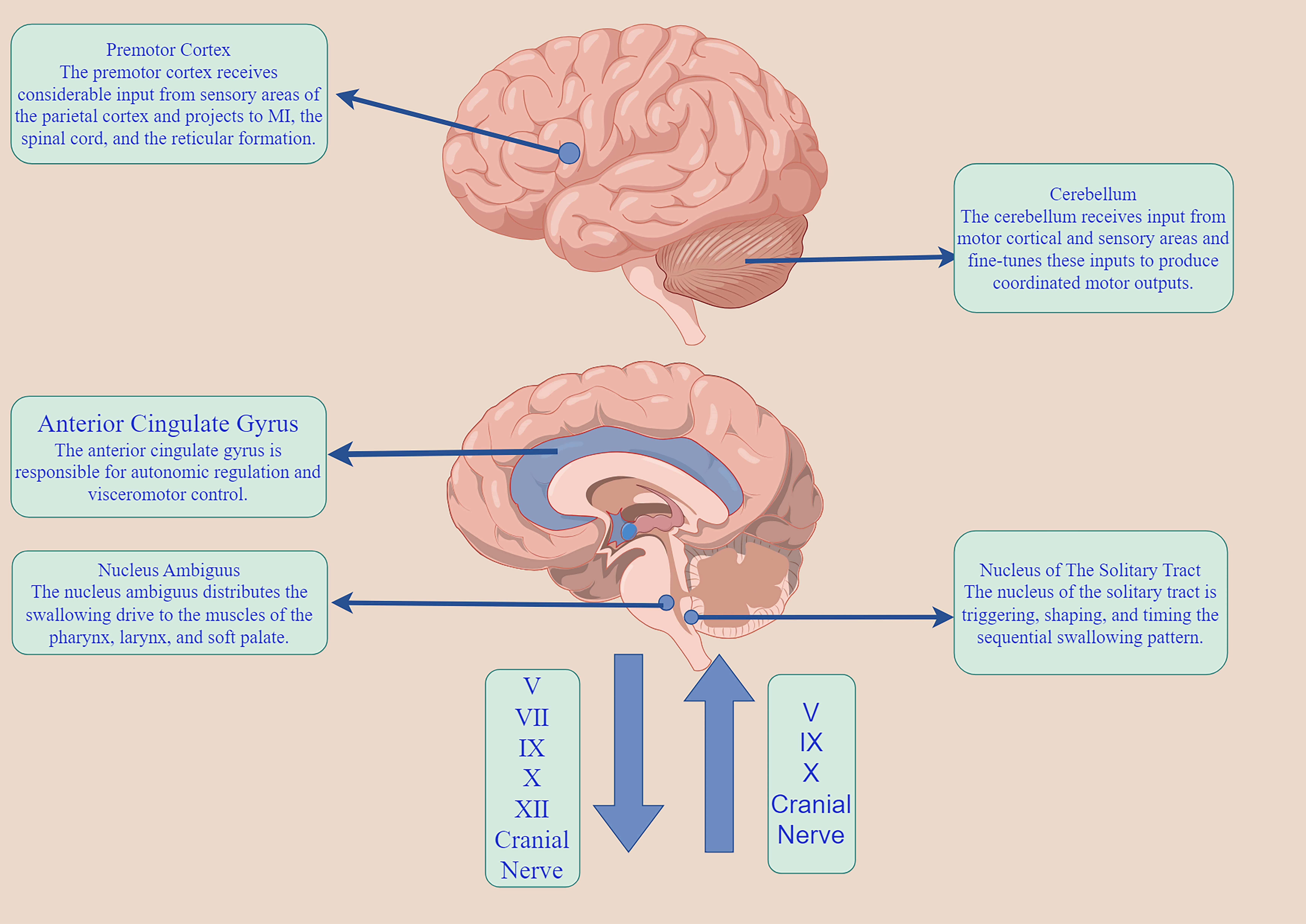

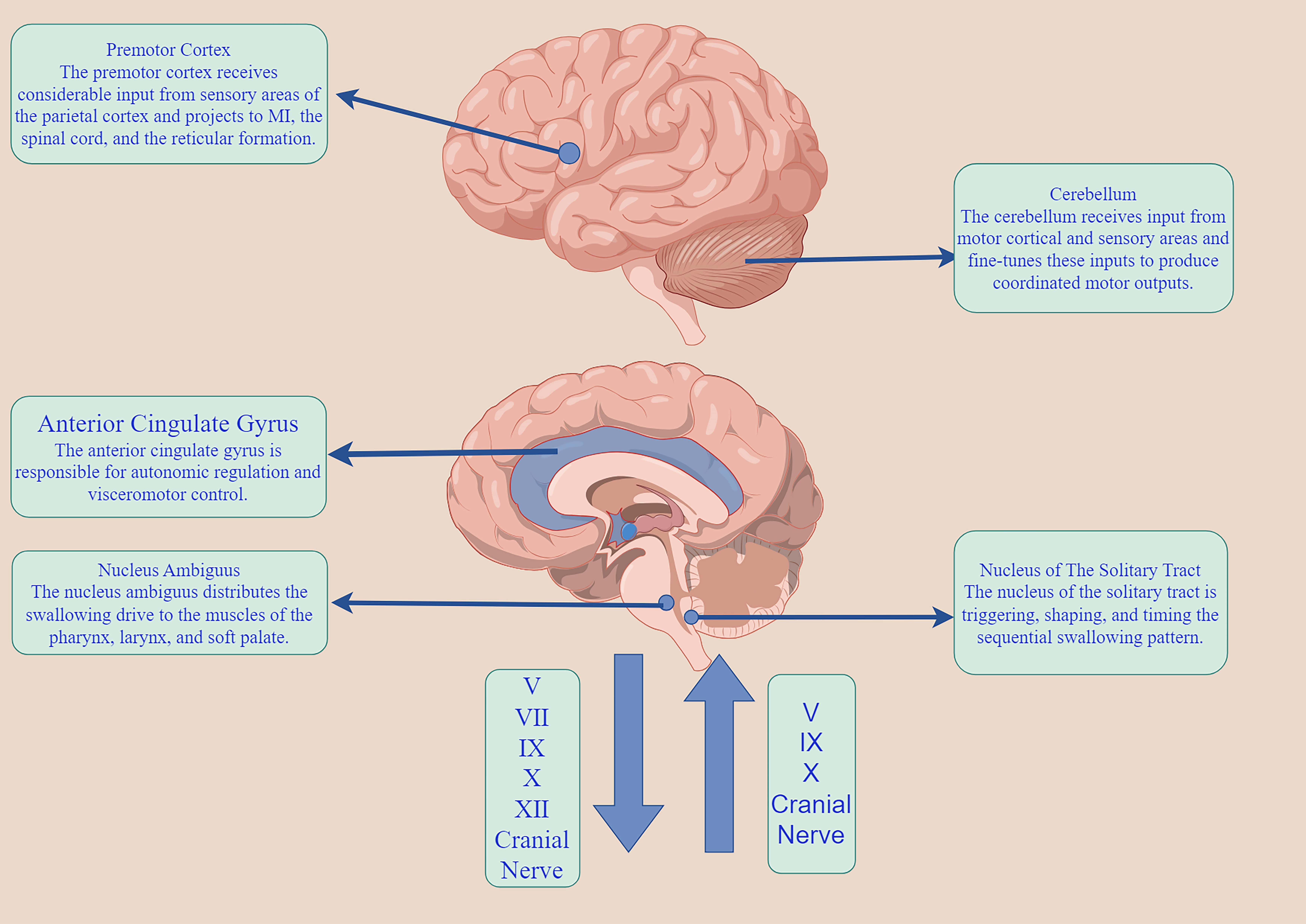

The neuromodulatory mechanism of swallowing is a very complex neurophysiological mechanism. The normal pharyngeal reflex is a pattern generator of peripheral stimulation to the swallowing center, which is transmitted from the sensory nucleus (the solitary nucleus to the motor nucleus) to the nucleus ambiguous, to complete the corresponding swallowing reflex activity [14]. According to the size of the specific swallowing pellets, the swallowing intensity and time are adjusted, resulting in the lifting of the soft palate and reflex contraction of the nasopharynx, so that the pellets enter the pharynx smoothly. In the resting state, the upper esophageal sphincter (UES) remains contracted to maintain the resting pressure, ensuring closure of the proximal esophagus. This contraction prevents gas from entering the esophagus and stops intra-esophageal gas from entering. The normal pharyngeal reflex, a peripheral stimulus, reaches the central pattern generator of swallowing. It is transmitted from the nucleus of the sensory nerve (the nucleus of the solitary tract) to the nucleus of the motor nerve (the nucleus of the solitary tract), to complete the corresponding swallowing reflex activity [14]. The esophagus helps to stop the backflow of esophageal contents into the pharynx, with the cricopharyngeal muscle (CP) being the primary part of UES. When the regurgitation enters the pharynx during swallowing, the cricopharyngeal muscle is shifted towards the oral cavity by 2–3 cm. The epipharyngeal, mesopharyngeal, and hypopharyngeal muscles are then contracted to generate the pressure to push the regurgitation downward and minimize pharyngeal residues. At the same time, the UES must be reflexively diastole before the esophageal mass reaches the pyriform recess, opening the esophageal passage to accommodate entry of the esophageal mass. At the same time, the epiglottic cartilage is turned over in time to ensure that the esophageal mass does not enter the airway, then the UES contracts and passes the pressure downwards peristaltic to allow the esophageal mass to enter the stomach smoothly. The cerebral cortex can receive input from the nucleus of the solitary tract through the mesencephalon. The pharyngeal phase of swallowing is an intricate mechanical procedure that cannot be reversed once started. In contrast, the oral phase of swallowing is independent and regulated by the basal ganglia. It also receives signals from the insula and the anterior cingulate gyrus (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

The swallowing neuromodulatory network. M1, primary motor cortex. The figure was made by Figdraw (https://www.figdraw.com).

According to Braak’s hypothesis [8, 15], the initial appearance of PD lesions occurs in the dorsal motor nucleus, the anterior olfactory nucleus of the VN, and the glossopharyngeal nerve. This is followed by progressive involvement of the brainstem and cortex. The VN, which is the cranial nerve with the longest travel distance and widest distribution in the human body, provides sensory and motor functions to the pharynx through its pharyngeal branch, glossopharyngeal reentry nerve, and superior laryngeal nerve. The pharyngeal subjacent nerve, which consists of the VN pharyngeal branch and sympathetic nerve, innervates the CP and the pharyngeal constrictor (PC). The pharyngeal accessory nerve consists of the pharyngeal branch of the VN, the glossopharyngeal nerve, and the sympathetic nerve, which can control the CP, and the PC [16, 17, 18]. In autopsies of patients with PD [19], muscle fiber histology of the specimens revealed that the PC showed muscle atrophy and the fiber type appeared to be converted from fast twitch fiber to slow-twitch fiber, whereas the CP showed hypertonicity. However, the muscle contraction sequence in the pharyngeal phase [20] is initiated by specific sensory stimuli, not by tactile stimulation of the pharyngeal muscles by the esophageal mass. Instead, it is triggered by the pressure generated from the contraction of the pharyngeal muscles, which is then transmitted to the nucleus of the solitary fasciculus through the VN, the glossopharyngeal nerve, and the trigeminal nerve. Therefore, dysphagia in individuals with PD does not solely arise from the CNS; instead, it can occur due to a discrepancy between the performance of the peripheral nerves (specifically the cranial nerves associated with the VN) and the CNS (particularly the brainstem and limbic system).

Previous therapeutic measures for dysphagia in PD patients have focused on motor training of the oropharynx (mainly supraglottic and expiratory muscle strength training) and sensory stimulation (e.g., ice stimulation). However, these treatment protocols do not cure dysphagia, which may be the result of cortical adaptive compensation [21]. In motor control, there are currently two parallel loops proposed: the striatum-thalamo-cortical (STC) loop and the cerebellar-parietal-premotor (CPP) loop [22]. In PD, the supplementary motor areas experience a significant reduction in activation due to decreased excitability of the putamen nuclei. Additionally, the thalamic motor nuclei are excessively inhibited by the pallidum. However, the cortical premotor areas remain relatively active during this time. This is because the dorsolateral premotor cortex receives projections mainly from the unaffected caudate nucleus, which compensates for early STC deficits through cortical recruitment. Furthermore, the parietal cortex, responsible for sensation, motivation, and attention, can subconsciously prompt the organism to enhance sensory guidance in alignment with motor execution [21]. Therefore, swallowing disorders in early PD patients are severely underestimated, and even the patients themselves fail to detect the reduced swallowing function in time. As the disease progresses, this compensatory mechanism gradually fails, and swallowing disorders seem to arise in the patient in an instant, but in reality, the change is subliminal.

High-resolution pharyngeal impedance manometry (HRPIM) is beginning to be used in clinical evaluation for dysphagia, in particular cyclopharyngeal dysphagia, which can more objectively reflect the change in UES function, so as to better explain the pharyngeal pathophysiological mechanism and find more effective treatment options [23]. The indicators commonly used to evaluate the disorder include (1) UES lumen occlusive pressure, which is the pressure of esophageal closure caused by the contraction of the UES muscles in a calm state, which should be measured before and after swallowing respectively; (2) intrabolus pressure (IBP) refers to the resistance of the UES to the food mass during swallowing. Abnormally elevated IBP indicates an increased pressure gradient at the pharyngoesophageal junction; (3) integrated relaxation pressure (IRP), that is, the pressure during the maximum relaxation period of UES; and (4) the degree and duration of UES opening. The opening of the UES comes from the pressure generated by the contraction of the pharyngeal muscles and is determined by the intensity and timing of activation of the suprahyoid and subhyoid muscles [24]. These indicators can help us identify subtle changes in early dysphagia in PD patients. An investigation of pharyngoesophageal dyskinesia in patients with early PD revealed [25] that pharyngeal and esophageal dyskinesias are present in patients with early PD before they show symptoms of dysphagia, that patients often complain of a foreign body sensation in the pharynx during swallowing and the need to swallow several times before completing a single injection, that pharyngeal manometry shows abnormalities in the peristalsis of the esophageal sphincter, and that patients with PD show an erroneous contraction timing in the pharyngeal phase in early life, and that this error occurs significantly earlier than in the case of limbic dyskinesias. This suggests that hypophagia is not simply neuronal loss and dopamine deficiency but that the body compensates for this by using oropharyngeal sensation and movement. Dysphagia severity is evaluated using fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES) and video fluoroscopic swallowing studies (VFSS) which are considered the benchmark for diagnosing dysphagia. Both can accurately identify the penetration and aspiration of pharyngeal swallowing and the ability of the airway to clear foreign objects. Patients can be evaluated semi-quantitatively according to Penetration Aspiration Scale (PAS) grading. VFSS with video recording function can objectively record the changes in pharyngeal transit time (PTT) and the time of UES opening. For the evaluation of Parkinson’s dysphagia, it can more keenly observe achalasia of cricopharyngeus muscle disorder and distinguish it from the difficulty of injection caused by pharyngeal contraction muscle weakness. Conversely, HRPIM can identify subtle changes in the early stages of a patient’s life by quantifying the dynamic changes in pressure and time from the Eustachian tube to the UES during swallowing. It can also provide an objective basis for disease progression and improvement of treatment outcomes [26]. There is no doubt that FEES and VFSS are widely used in clinical practice due to their versatility and convenience, while HRPIM is susceptible to multiple factors, such as the age of the subject, bolus size, and bolus consistency, although HRPIM is still a very favorable diagnostic method for the evaluation of swallowing disorders in the pharyngeal stage.

At present, the pathological mechanism of PD in swallowing function is still unclear, but swallowing disorder in PD patients cannot be regarded as a simple movement disorder, and abnormal contraction timing in the pharyngeal period during swallowing may be the most important cause of aspiration. This systematic review incorporates multiple types of treatment options, including pharmacologic treatment, exercise therapy, physical factor treatment, the swallowing strategy, neuroregulatory techniques, and UES resistance reduction therapy. The purpose was to identify more sensitive diagnostic tools and more effective treatment methods, and provide supporting evidence for the establishment of larger randomized controlled trials in the future.

This systematic review protocol was designed and performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guideline (PRISMA_2020_checklist can be seen in the Supplementary Materials) [27]. This systematic review was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42024522754).

We systematically explored databases, such as PubMed, Web of Science, Elsevier, and Cochrane Library, to find clinical studies published in multiple languages until December, 2023. Our search involved using the terms ‘Parkinson’s disease’ AND ‘dysphagia’ OR ‘deglutition disorder’ AND ‘rehabilitation’ OR ‘physiotherapy’ OR ‘physiotherapy treatment’. In addition, we manually searched for additional studies that might be relevant.

In our comprehensive analysis, we examined trials that investigated the impact of different therapies on dysphagia in individuals diagnosed with PD. We established specific criteria based on the PICOS principles: P (Population)—patients with PD experiencing dysphagia; I (Intervention)—any treatment aimed at addressing dysphagia; C (Comparison)—comparing experimental groups with control groups (including placebo or blank groups); O (Outcome)—evaluating HRPM, FEES, VFSS, and various swallowing assessment scales; and S (Study design) — focusing on randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Exclusion criteria: (1) duplicate studies, (2) review articles, and (3) the full article cannot be obtained.

The retrieved literature was imported into Endnote20 (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA), and the titles and abstracts were read repeatedly by two researchers to determine the literature to be included, with discussion with a third researcher in case of disagreement. Where similar lines of research existed, only the most recent trials were included.

According to the Cochrane Handbook, data were extracted from the included studies by two researchers, including the article’s first author, year of publication, title, sample size, basic information about the subjects, subgroups, intervention modality, length of intervention, diagnostic tools, and outcomes.

Two researchers evaluated the trial’s quality using the Cochrane Collaboration tools, which encompassed seven domains for assessing bias risk: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of investigator and subjects, blinding of outcome assessment, follow-up bias, selective reporting, and other sources of bias. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third researcher.

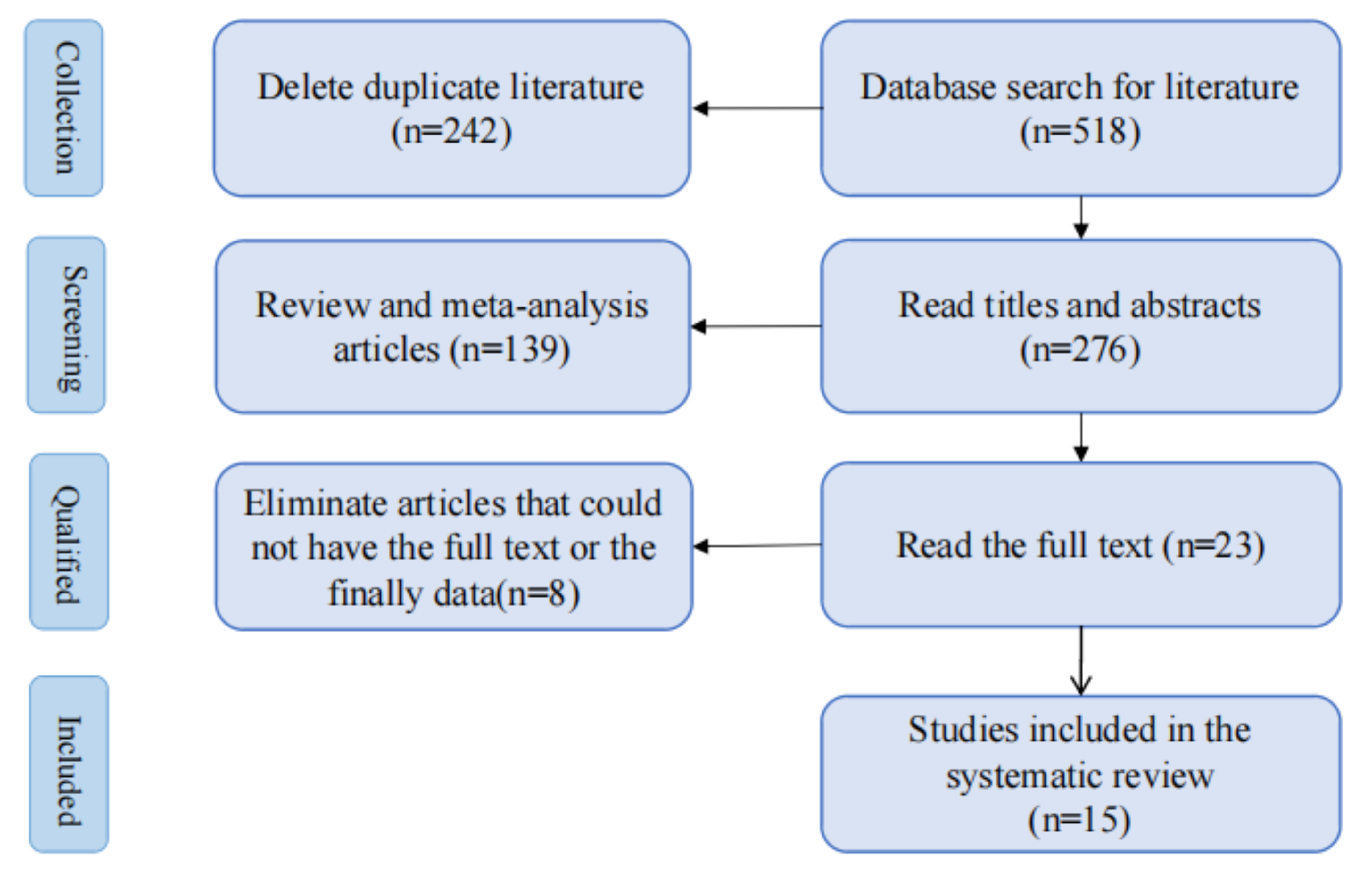

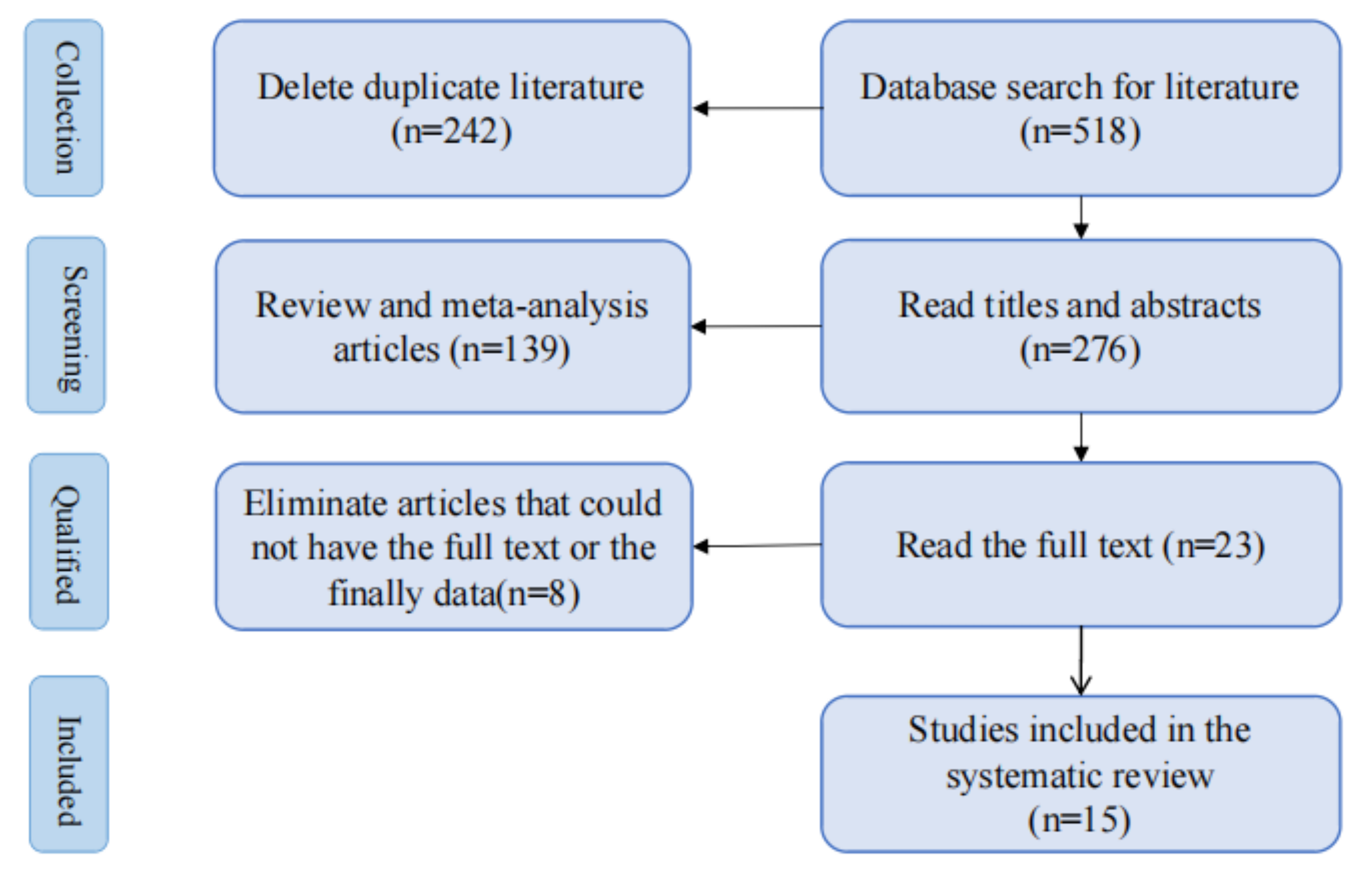

Five hundred ninety-six papers matching the search strategy were retrieved from the databases. After deleting duplicate studies, 18 relevant studies were retained after reviewing article titles and abstracts. After reading the complete text, five full texts were not found, three lacked final results, 10 randomized controlled trials were obtained, and we manually searched for two more before-and-after controlled trials, as we did not retrieve any randomized controlled trials of studies related to the lowering of resistance to UES. Ultimately, our systematic review included 15 studies [28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42] (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Flowchart outlining the article screening process.

A total of 519 patients were included in 15 studies, all of whom were assessed for motor ability using the H-Y classification. Most of the staging was between 2–4, all of whom underwent a variety of treatments for dysphagia, which included oropharyngeal muscle exercise therapy [32, 38], physical factor therapy [29, 30, 35], swallowing strategies [28, 31, 33], neuromodulation techniques [36, 37], and UES resistance reduction techniques [34, 39]. FEES [31, 33, 37, 38], VFSS [28, 29, 32, 35, 36, 39], and HRPIM [34, 39] were used in the majority of studies. One or two of these three diagnostic modalities are recognized as having high confidence, which reduces the error in the study results to some extent. The general information and characteristics of the patients included in the study are shown in Table 1 (Ref. [28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42]).

| Author/Year | Age (years) | H-Y Stage | Clusters | Type of Intervention | Duration of Intervention | Diagnostic Tool | Conclusion |

| Ayres et al. 2017 [33] | EG: 62 |

EG: 2.8 |

EG: 10 | EG: Chin-down swallowing + eating movement guide | 4 weeks | FEES+FOIS+SWAL-QOL | The chin-down maneuver is a safe and convenient measure that can improve swallowing function and subjective feeling of PD patients. |

| CG: 62.8 |

CG: 2.5 |

CG: 8 | CG: No intervention | ||||

| OG: 64.5 |

OG: 2.5 |

OG: 6 | OG: Eating movement guide | ||||

| Logemann et al. 2008 [28] | 50–95 | Unclear | 117 patients, three groups | Each patient was randomized to receive a swallowing strategy of low-thickness fluids, high-thickness fluids, and chin-down swallowing | Once | VFSS | Highly thickened fluids are more effective than chin-down swallowing and low-thickness in eliminating aspiration, and the patient’s state of consciousness can affect compliance with swallowing strategies. |

| Heijnen et al. 2012 [30] | 42–81 | 1–4 (median = 2) | The TT group received conventional swallowing rehabilitation, the NMES-M group increased neuromuscular electrical stimulation at the motor level, and the NMES-S group increased neuromuscular electrical stimulation at the sensory level | 15 treatments | FOIS+SWAL-QOL+MDADI | All groups showed a significant therapeutic effect, and the difference between groups was not obvious. | |

| Group TT: 28 | |||||||

| Group NMES-M: 27 | |||||||

| Group NMES-S: 30 | |||||||

| Park et al. 2018 [35] | EG: 63.44 |

Unclear | EG: 9 | The EG received NMES + forceful swallowing strategy, and the OG group received sham NMES + forceful swallowing strategy | 4 weeks | VFSS+VDS+PAS | NMES acting on the infrahyoid region can increase movement of the hyoid bone and reduce the incidence of aspiration. |

| OG: 54.67 |

OG: 9 | ||||||

| Baijens et al. 2012 [29] | EG mean age: 66 | Median = 2 | EG: 10 | Each patient was randomized to receive one of three different positions of electrode stimulation, and the motor was randomized to be on/off | 2 weeks | VFSS | Surface electrical stimulation can improve swallowing function in patients with PD. However, the same effect was seen in the sham stimulation group, and these effects may be mainly caused by the placebo effect. |

| OG mean age: 65 | OG: 10 | ||||||

| Manor et al. 2013 [31] | EG: 67.66 |

EG: 2.21 |

EG: 21 | The EG added VAST therapy to conventional treatment, and the OG group received only traditional treatment | Six times | FEES+SWAL-QOL | VAST is effective in preventing pharyngeal retention and can improve patient understanding and implementation of swallowing strategies. |

| OG: 69.86 |

OG: 2.19 |

OG: 21 | |||||

| Claus et al. 2021 [38] | EG: 67.3 |

2–4 | EG: 25 | The EG received EMST training using standard equipment, and the OG group received training using sham equipment | 4 weeks | FEES+MEG | EMST significantly reduces improved swallowing function in PD patients, and this effect lasted for up to 3 months, but there were no changes in the MEG inspect. |

| OG: 67.1 |

OG: 25 | ||||||

| Byeon et al. 2016 [32] | EG: 65.1 |

EG. | EG: 15 | The EG received postural substitution + EMST, and the OG group received EMST only | 4 weeks | VFSS | EMST combined with postural substitution is more effective than EMST alone in the swallowing rehabilitation for patients with dysphagia caused by PD. |

| OG: 63.8 |

OG. | OG: 18 | |||||

| Pflug et al. 2020 [37] | EG: 63.4 |

Unclear | EG: 15 | The EG was assessed within the DBS off, STN-DBS, and STN+SNr-DBS phases, each lasting 3 weeks | Once | FEES | Combined deep brain stimulation of STN + SNr can improve axial symptoms and gait disorders in PD patients without adverse effects on the patient’s swallowing function. |

| OG: 68.1 |

OG: 32 | The OG group was a healthy control population | |||||

| Wu et al. 2021 [39] | EG: 55–79 | EG: 2–4 | EG: 8 | C-POEM was performed on patients | Once | HRPIM+VFSS+SSQ+SWAL-QOL | C-POEM can effectively reduce UES pressure, thereby reducing the resistance of UES to food during swallowing, so that food can safely pass through the esophagus. |

| Triadafilopoulos et al. 2017 [34] | EG: 62–93 | EG: 2–5 | EG: 3 | Perform endoscopic BoNT injections for patients | Once | HRPIM | Endoscopic BoNT injection to the esophagus can significantly improve patients’ cricopharyngeal function, and this effect can last for several months. It is safe and well-tolerated by patients. |

| Khedr et al. 2019 [36] | EG: 60.7 |

EG: 3.1 |

EG: 22 | The EG received real rTMS stimulation | 3 months | VFSS+A-DHI | rTMS can significantly improve swallowing function in patients with PD. |

| OG: 57.4 |

OG: 3.5 |

OG: 11 | The OG group received sham rTMS stimulation | ||||

| Restivo et al. 2002 [41] | EG: 58–72 | Unclear | EG: 4 | Patients were given endoscopic BoNT injections | Once | VFSS | VFSS showed the patient’s swallowing function and coordination between the cricopharyngeal and inferior constrictor muscles tended to be normal, and there was a marked reduction in cricopharyngeal hyperactivity. |

| Huang et al. 2022 [42] | EG: 60.32 |

EG: 2.13 |

EG: 38 | The EG received high frequency rTMS | 10 times | fMRI | Patients reported improved subjective swallowing sensations after rTMS. fMRI showed increased activation of the parahippocampal gyrus, caudate nucleus, and left thalamus in patients after treatment. |

| OG: 56.23 |

OG: 0 | OG: 30 | The OG groups received no intervention | ||||

| Born et al. 1996 [40] | Unclear | Unclear | EG: 4 | The EG received C-POEM | Once | HRPIM | There was a significant and sustained improvement in the patients’ swallowing function. |

Abbreviations: M, motor; S, sensory; EG, experimental group; CG, control group; OG, orientations group; FOIS, Functional Oral Intake Scale; SWAL-QOL, quality of life-related to swallowing; MD, Monroe Dunaway; MDADI, MD Anderson Dysphagia Inventory; VAST, video-assisted swallowing therapy; PAS, penetration-aspiration scale; VDS, Videofluoroscopic Dysphagia scale; EMST, expiratory muscle strength training; MEG, magnetencephalography; STN, subthalamic nucleus; SNr, substantia nigra; C-POEM, cricopharyngeal peroral endoscopic myotomy; rTMS, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation; NMES, neuromuscular electrical stimulation; H-Y, Hoehn and Yahr; A-DHI, Arabic-Dysphagia Handicap Index. FEES, fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing; VFSS, video fluoroscopic swallowing study; HRPIM, high-resolution pharyngeal impedance manometry; fMRI, functional magnetic resonance imaging; PD, Parkinson’s disease; UES, upper esophageal sphincter; SSQ, Sydney swallowing queationnaire; DBS, deep brain stimulation; BoNT, botulinum neurotoxin; TT, traditional treatment.

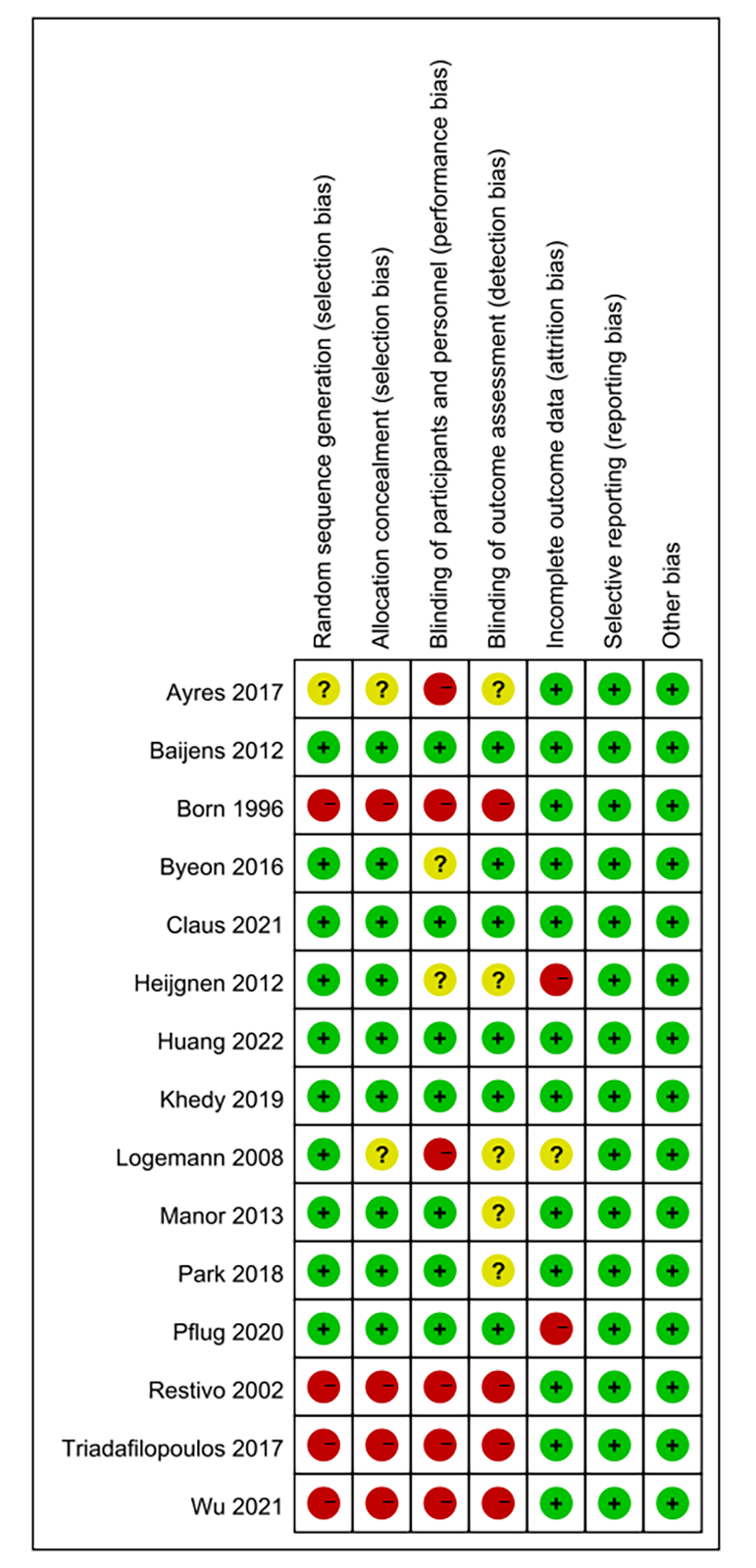

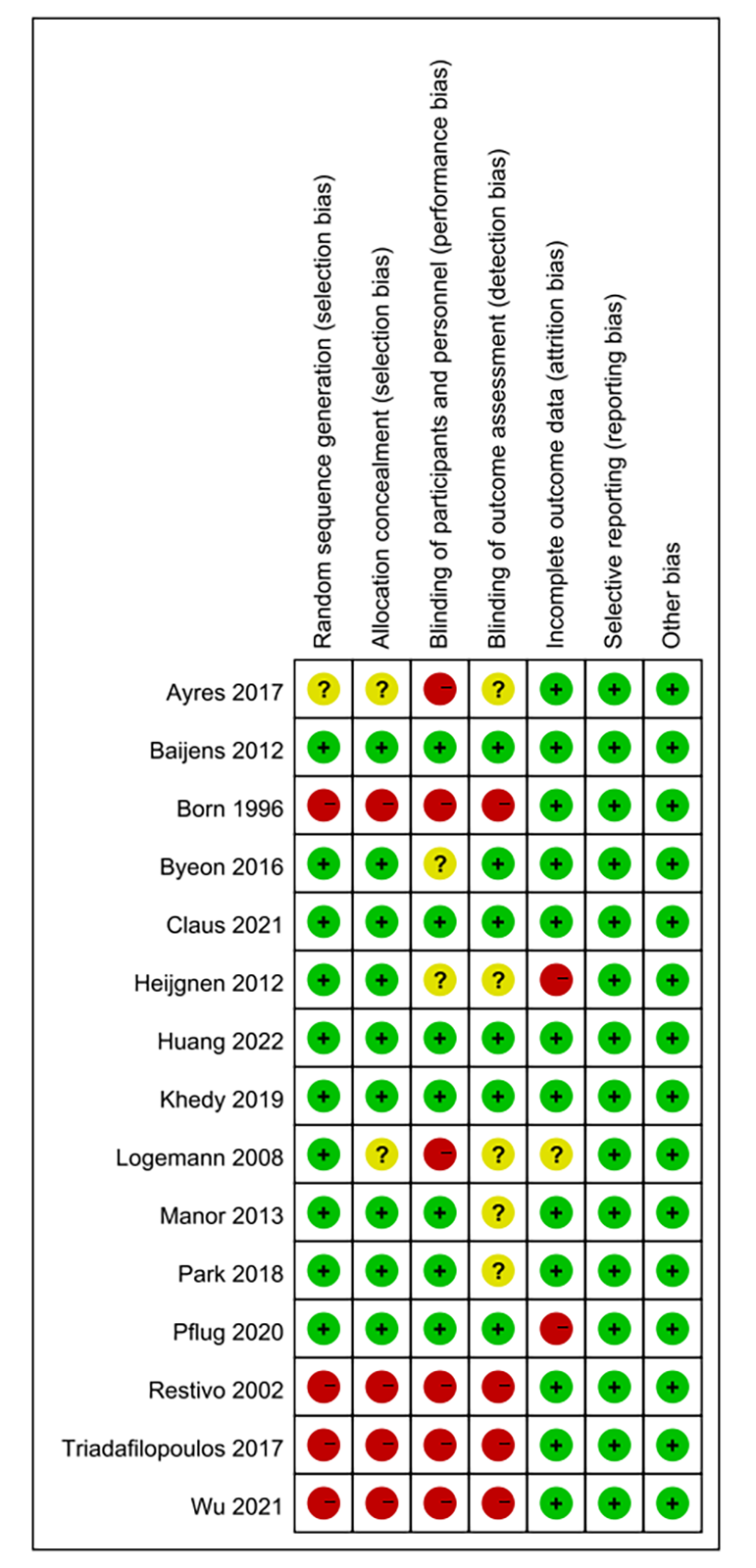

We assessed the risk of bias in 15 of the included studies, three of which did not report random sequences generation, three of which did not perform allocation concealment, five of which explicitly blinded participants and personnel, and six of which blinded outcome assessment. All had a low risk of bias in terms of selective reporting and incomplete outcome data. Fig. 4 shows the assessment of risk bias for the included literature.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Risk of bias results.

In a study by Ayres et al. [33], the FEES assessment did not show any

difference between the three groups, while a comparison of the Functional Oral

Intake Scale (FOIS) showed that the experimental group (EG) showed significant

improvement in swallowing solids (p

In the report by Logemann et al. [28], the VFSS results of the three

groups were compared. It was found that the high-thickness group had

significantly fewer subjects experiencing aspiration compared with the

low-thickness group (53% versus 63%, p

Heijnen et al. [30] compared the SWAL-QOL and Monroe Dunaway (MD) Anderson Dysphagia

Inventory (MDADI) within each group before and after treatment. The Wilcoxon

signed-rank test revealed significant changes in the symptom indices of each

group. However, these changes were not statistically significant (p =

N.S.), and no significant correlation was found between the scales (R

Park et al. [35] utilized the VFSS to observe significant variations in the amplitude of horizontal (p = 0.038) and vertical (p = 0.042) movements of the hyoid bone between the test group and the placebo group. Additionally, the test group showed significant differences in the Videofluoroscopic Dysphagia scale (VDS) total score (p = 0.021), pharyngeal phase score (p = 0.028), and penetration-aspiration scale (PAS) score (p = 0.007) during the scale assessment. Conversely, the placebo group only demonstrated a significant difference in the total score (p = 0.041), indicating an improvement. Furthermore, when comparing the two groups, a substantial difference in the PAS score was found in the test group (p = 0.039).

Baijens et al. [29] discovered that the statistical significance of electrical stimulation and its location (supraglottic, subglottic, or combined) was insignificant. However, stimulation of the subglottic muscle group did show a significant difference in reducing the average time it takes for the laryngeal opening to occur compared with the combined stimulation method. Interestingly, the sham-stimulation group also exhibited the same effect. This suggests that surface electrical stimulation may impact swallowing function in PD, but it could be attributed to a placebo effect.

In a study by Manor et al. [31], the video-assisted swallowing therapy

(VAST) team demonstrated a more significant enhancement in the occurrence of

leftover food during FEES compared with the control group. The initial

measurements were 1.73

Claus et al.’s [38] FEES study indicated that the EG exhibited a

notable enhancement in residue scores (p

The study of Byeon et al. [32] conducted in 2016 demonstrated that

after treatment, the videofluoroscopy (VFS) scale scores decreased in both

groups. However, the combined intervention group exhibited a more significant

decrease than the EMST group (p

Pflug et al. [37] demonstrated that there was no notable alteration in the average measurements of swallowing capacity at the start when compared with the average measurements of PAS and residues under the stimulation modes of deep brain stimulation with Subthalamic Nucleus (STN-DBS) or deep brain stimulation with Subthalamic Nucleus and Substantia nigra (STN+SNr-DBS), as determined by Friedman tests. The research findings indicated that STN+SNr-DBS does not provide any additional impact on the swallowing functionality compared with STN-DBS. If the application of STN+SNr-DBS is intended for enhancing axial symptoms and gait disorders in PD patients, it can be deemed safe with dysphagia.

In a study by Wu et al. [39], the comparison between the patient’s UES integrated relaxation pressure (IRP) before and after surgery showed a decrease from 13.7 mmHg to 3.6 mmHg, with a mean difference of –10.1 mmHg (95% confidence interval (CI) [–16.3, –3.9], p = 0.007). Additionally, the average hypopharyngeal intrabolus pressure (IBP) decreased from 23.5 mmHg to 10.4 mmHg, with a mean difference of –11.3 mmHg (95% CI [–17.2, –5.4], p = 0.003). It was demonstrated that cricopharyngeal peroral endoscopic myotomy (C-POEM) could induce the relaxation of the UES, thus reducing the resistance during swallowing and promoting the improvement of swallowing function.

Triadafilopoulos et al. [34] conducted a study involving three individuals who received botulinum neurotoxin (BoNT) injections for dysphagia in their UES. All three patients showed enhanced swallowing ability, and the average duration of the impact was 8.3 months (ranging from 1 to 2 to 3 months, with a 95% CI of 2–13.6 months). In patients with PD, injections of BoNT into the esophageal sphincter have demonstrated efficacy in alleviating dysphagia. Moreover, this treatment is considered feasible, well-tolerated, and safe for repeated use.

In the study by Khedr et al. [36], a two-way repeated measures analysis

of variance was conducted for each Arabic-Dysphagia Handicap Index (A-DHI) score.

The main factors were treatment condition (real repetitive transcranial magnetic

stimulation (rTMS) versus sham rTMS) and time (baseline, post-treatment, after 1,

2, and 3 months). The results indicated that the average decrease in the A-DHI

was significantly more significant in the real group (14.4

A study by Restivo et al. [41] included only four patients. After percutaneous injection of BoNT into a bilateral cricopharyngeal muscle, the patient showed significant improvement in swallowing function 48 hours later, and this effect lasted for more than 20 weeks. Meanwhile, VFSS showed that the coordination between the cricopharyngeal muscle and the pharyngeal constrictor muscle was normal, the symptoms of cricopharyngeal muscle spasm were significantly improved, and the patient’s body weight was significantly increased.

Huang et al. [42] described 38 PD patients with dysphagia that were treated with high-frequency rTMS for 10 days. After treatment, all patients reported subjective improvement in swallowing function. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) examination was performed before and after treatment to observe the brain activation of patients when swallowing saliva, and compared with fMRI of 30 healthy people. A general linear model was used to make a statistical parameter graph for each individual subject, and the two-sample t test was used to compare the activation difference of rTMS between the EG and orientations group (OG) and within the EG before and after treatment. The results showed that, compared with the OG, the activation degree of the anterior central gyrus, auxiliary motor area, and cerebellum was higher in the EG before treatment, while the activation degree of the parahippocampal gyrus and caudate nucleus was lower. Activation of the parahippocampal gyrus and caudate nucleus increased after treatment, suggesting that high frequency rTMS may induce neural plasticity.

Four patients were included in Born et al.’s [40] study. HRPIM examination proved that the patients had cyclopharyngeal dysfunction. After C-POEM surgical intervention, the patients all showed significant and lasting improvement in swallowing function. Therefore, for dysphagia in Parkinson’s patients, we should carefully evaluate the patients’ cyclopharyngeal function. When patients have obvious cyclopharyngeal dysfunction, C-POEM surgery can play an irreplaceable role in other treatments.

Given that pharmacological treatment is always present throughout PD, this systematic review did not include drug-related studies. Despite the widespread use of dopaminergic medications, particularly levodopa, in clinical settings, these drugs can provide external dopamine supplementation to patients and effectively alleviate motor symptoms. In advanced cases of PD, where motor function fluctuates with changes in dopamine levels, the stimulation of levodopa can significantly enhance the body’s compensatory ability to improve airway protection and subsequently lead to a notable enhancement in swallowing function [43]. Despite extensive research backing the enhancement of swallowing ability through levodopa, its impact on individuals in the early stages of PD remains inconclusive [44]. Swallowing difficulties in PD are believed to stem from a combination of dopaminergic and non-dopaminergic degeneration.

Exercise therapy is now widely used to improve the movement disorders in PD patients. Exercise therapy has achieved satisfactory results in both animal experiments [45, 46, 47] and human trials [48, 49, 50], especially high-intensity exercise, which can improve the plasticity of motor nerves. The targeted training of relevant muscles in PD patients to solve the problem of dysphagia has also been widely used by swallowing therapists in clinical practice. In particular, with EMST therapy, the improvement of expiratory muscle strength can significantly improve the patient’s coughing, i.e., airway clearance, thus helping to reduce aspiration or leakage. On the other hand, EMST induces the activation of the sub-chin muscles, leading to the elevation of the tongue-laryngeal complex. One study has shown that [51], after 4 weeks of EMST intervention, the electromyography (EMG) signal of the expiratory muscle showed longer duration, higher peaks, greater mean amplitude, and a significant improvement in PAS.

Although physical factor therapy is now widely used for functional recovery after CNS lesions, the role it plays in PD remains debatable, so more research is needed to elucidate the therapeutic effect and mechanism of action of physical factors for dysphagia in PD.

The swallowing strategy is currently the most widely used and cost-effective intervention for patients with PD, which achieves safe swallowing by utilizing safer swallowing postures, more adapted food forms, or more potent sensory stimuli. Although the swallowing strategy does not improve swallowing function, it can provide patients with a more soothing subjective eating experience. Commonly used swallowing postures include chin-down swallowing, lateral swallowing, and semi-sitting swallowing. One effective technique for PD patients is chin-down swallowing, which involves bringing the chin closer to the neck. This action shortens the distance between the tongue’s base and the throat’s back while preventing food from prematurely falling into the pharynx. The increase in viscosity of the food mass results in higher internal tension, making it easier for the food mass to gather. This allows the patient to have better control over the food mass during oral and pharyngeal phases, reducing the risk of aspiration. In clinical settings, thickener is commonly used to prepare liquid that matches the patient’s feeding consistency. This method is widely used in conjunction with postural compensatory training. However, it is essential to note that prolonged consumption of highly thickened liquid may lead to dehydration. It should only be considered a temporary solution during improved swallowing function rather than a long-term strategy. Considering the adverse feeding experience associated with thickened liquids, the subjective choice and compliance of the patient are also things we need to consider when looking for a swallowing strategy that applies to the patient. Furthermore, the more fluid the consistency, the greater the patient’s ability to control the doughnut and the safer the swallowing process. However, this also places higher demands on the patient’s tongue muscles as they need to exert pressure to propel the doughnut into the pharynx. Therefore, the appropriate liquid consistency should be determined based on the patient’s circumstances. VAST is a form of sensory stimulation that complements the swallowing action. By observing a video of themselves swallowing, patients can enhance their visual perception and ensure the successful completion of the swallowing process. This approach can improve the patient’s feeding and swallowing experiences. Completing the swallowing action can increase the fun of the patient when eating. It is essential to mention that VAST might only be beneficial for individuals with mild to moderate dysphagia who have PD, and there is insufficient evidence to support the therapeutic benefits of VAST in patients with advanced stages of PD.

Neuromodulation is a rapidly evolving field and, as we delve deeper into the nervous system, it has transformed into a therapy that can exert a targeted effect on specific symptoms. In the case of dysphagia, whether it is deep brain stimulation (DBS), transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), or transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), all these methods have demonstrated effectiveness. However, there is a need for authoritative therapeutic protocols encompassing the stimulation’s target point, mode, intensity, and duration, which should be validated through numerous clinical trials to establish their superiority. DBS, commonly known as “brain pacemaker”, is a minimally invasive, reversible, and adjustable surgery on the brain in which electrodes are implanted into specific locations in the brain area, and the electrical impulses emitted by the electrodes are used to regulate abnormal brain discharges, thus achieving the purpose of treating PD. DBS is often applied to PD patients who develop severe resistance to dopaminergic drugs. There is a need for more reliable treatment guidelines for DBS, with the commonly targeted areas being the STN and the globus pallidus internum (GPi). The treatment of DBS in the advanced stages of the disease focuses on reconstructing the motor control loops, particularly the STN and pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus (PPN). The PPN is connected to the GPi and substantia nigra (SNr) through parallel motor loops [52]. Additionally, the PPN serves as a relay station for transmitting inputs to the nucleus of the solitary tract and plays a crucial role in the swallowing center. However, it is still unclear whether DBS is beneficial or detrimental to dysphagia [53]. A recent study [37] have shown that combined STN+SNr stimulation improves dyskinesia without negatively affecting swallowing function. Therefore, it can be considered a viable stimulation target. TMS is widely used for dyskinesia, cognitive deficits, and dysphagia resulting from neurological injuries, making it a promising therapeutic approach. It restores the temporal sequence of swallowing movements by bi-directionally modulating cortical excitability, re-establishing bilateral hemispheric balance so that commands from each hemisphere can be effectively delivered to both sides of the brainstem, integrating the cranial nerves utilized in the swallowing process.

Therapies to reduce the UES resistance are now progressively being used to treat cricopharyngeal dysphagia in PD. According to a study related to pharyngeal manometry, at least 20–30% of all swallowing in PD patients is associated with UES loss of relaxation [54]. The specific manifestations are increased resistance to the passage of the esophageal mass through the UES, decreased UES opening, and reduced duration of the UES opening due to the dysregulation of the swallowing time series or the increased tension of the UES itself, leading to a sense of obstruction during pharyngeal swallowing, which is often compensated for by forceful swallowing to alleviate the symptom and to generate more pressure by increasing the strength and duration of the pharyngeal reflexes, but this may reinforce this mis-sequencing [55]. Although forceful swallowing has been proven effective in the short term, it may not be a suitable method in the long run as it can speed up the transformation of the PC muscle from fast twitch to slow twitch fiber, resulting in weaker benefits compared with the harms it causes. Conversely, reducing the UES can have the opposite effect by decreasing the pressure on the PC muscle by lowering the resistance of the CP, thus aiding in restoring the timing of pharyngeal muscle contractions. C-POEM has been demonstrated to be a less intrusive and safer alternative. C-POEM is less invasive, has fewer adverse effects, helps relax the UES, and reduces swallowing resistance during swallowing, thus avoiding the occurrence of pharyngeal retention, infiltration, and aspiration and improving swallowing function. In PD, due to the lack of dopamine, the lack of inhibition of acetylcholine stimulation results in the occurrence of muscle tremors and bradykinesia. The injection of BoNT in the local area can prevent the release of acetylcholine from the neuromuscular junction, effectively stopping the transmission of nerve signals and muscle movement. This method is extensively employed to treat hypertonia caused by neurological disorders. This therapy is less invasive and can be used multiple times. It may cause some local side effects. BoNT has proven to be very effective in treating various non-motor symptoms of PD [56], such as excessive saliva, excessive sweating, digestive problems, urinary problems, and dysphagia. It can be injected directly into the UES to reduce resting UES pressure, making it a potential substitute for C-POEM due to its safety and effectiveness.

It is important to note that, unlike cerebrovascular lesions such as stroke, PD is a degenerative neurological disease and swallowing disorders gradually worsen as the disease progresses. Exercise therapies and swallowing strategies are the most potent guarantees for safe swallowing in early-stage PD patients. Still, this compensatory mechanism gradually fails as the disease progresses, and they cannot cure it alone. When selecting assessment tools, swallowing scales excessively emphasizes the patient’s subjective perception. Conversely, the FEES and VFSS primarily aim to depict the characteristics of symptom onset, such as premature food drop, pharyngeal retention, leakage, and aspiration. Although these tools can assist in comprehending swallowing movements over time when combined with video recording and processing software, their focus is limited to the area above the UES. There is a lack of quantitative assessment of the entire pharyngeal contraction timing, so the examiner’s skill level and subjective opinion can disturb the results. The insensitivity of the assessment tool thus leads to a significant overstatement of the role of conventional swallowing therapy; the use of HRPIM would be a perfect complement to both and has a higher sensitivity for early cricopharyngeal dysphagia. This systematic review includes four study on UES resistance reduction therapy. Patients all showed effective and continuous improvement of swallowing disorder in the pharyngeal stage after treatment, and the IRP and IBP of patients showed significant and continuous reduction after HRPIM examination, which proved that cyclopharyngeal dysfunction may be the primary cause of swallowing disorder in Parkinson’s patients. Therefore, UES resistance reduction therapy may be more effective than other treatments.

This study confirmed the beneficial effects of various treatment schemes of swallowing disorders in PD patients. However, due to the small number of included studies, insufficient sample size, heterogeneity of interventions and main outcomes (such as HRPIM and FESS), and differences at the individual level (such as age, sex, and course of disease), we did not conduct a meta-analysis. Therefore, more high-level evidence is needed to prove the effectiveness of the treatment. In addition, we suggest that HRPIM should be more included in the assessment of swallowing disorders, because it can identify the early decline of cyclopharyngeal function in PD patients earlier and is more suitable for horizontal comparison of the effectiveness of various treatments, which can make the data more reliable. In addition, since there is an on-off phenomenon in patients with advanced PD due to fluctuations in dopamine levels in the body, it is necessary to report in which state the study was carried out, especially for therapeutic intervention in patients with advanced PD. In the future, studies with larger sample sizes and blinded as much as possible are needed to determine the efficacy of different treatments for swallowing disorders in PD patients.

HRPIM is a reliable measure to evaluate alterations in the pharyngeal stage of the swallowing procedure, offering the benefit of being both harmless and responsive without radiation. Protocols that reduce UES resistance can help re-establish the timing of muscle contractions during the pharyngeal phase. Neuromodulation techniques are a favorable weapon for remodeling nerve function.

Swallowing is a multidimensional interaction between brain regions, the output of which is a sophisticated process of peripheral muscle coordination. In the future, we hope that large-scale studies will be conducted to establish staging criteria that can describe the degree of dysphagia in PD and that treatment plans can be developed that apply to all periods based on precise assessment.

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

FLN, SL HL and YZX codesigned the study and wrote the draft. XLZ and WXL were responsible for the literature search and exclusion. ZYL and HY performed the data analysis. WJN and GHZ were responsible for the methodology. LQ was responsible for the conceptualization. HL and YZX reviewed and edited the paper. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Thanks to all the peer reviewers for their suggestions and comments.

The present study was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2022MH124), the Shandong Medical and Health Technology Development Fund (202103070325), the Shandong Province Traditional Chinese Medical Science and Technology Project (M-2022216).

The authors declare no conflict of interest. Yuzhen Xu is serving as one of the Guest editors of this journal. We declare that Yuzhen Xu had no involvement in the peer review of this article and has no access to information regarding its peer review. Full responsibility for the editorial process for this article was delegated to François Ichas.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/j.jin2311204.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.