1 Key Laboratory of Ministry of Education for TCM Viscera-State Theory and Applications, Liaoning University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 110032 Shenyang, Liaoning, China

2 Department of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Liaoning University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 110032 Shenyang, Liaoning, China

3 Teaching and Experiment Center, Liaoning University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 110032 Shenyang, Liaoning, China

4 Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, The Second Hospital of Dalian Medical University, 116023 Dalian, Liaoning, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

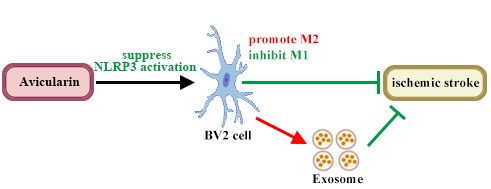

Avicularin (AL), an ingredient of Banxia, has anti-inflammatory properties in cerebral disease and regulates polarization of macrophages, but its effects on ischemic stroke (IS) damage have not been studied.

In vivo, AL was administered by oral gavage to middle cerebral artery occlusion/reperfusion (MCAO/R) C57BL/6J mice in doses of 1.25, 2.5, and 5 mg/kg/day for seven days, and, in vitro, AL was added to treat oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD)-BV2 cells. Modified neurological severity score, Triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) staining, brain-water-content detection, TdT-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assay, flow cytometry, immunofluorescence assay, Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and Western-blot analysis were used to investigate the functions and mechanism of the effect of AL treatment on IS. The exosomes of AL-treated microglia were studied by transmission electron microscope (TEM), nanoparticle tracking analyzer (NTA), and Western-blot analysis.

AL treatment reduced the neurological severity score, infarct volume, brain-water content, neuronal apoptosis, and the release of inflammatory factors, that were induced by MCAO/R. Notably, M2 microglia polarization was promoted but M1 microglia polarization was inhibited by AL in the ischemic penumbra of MCAO/R mice. Subsequently, anti-inflammatory and polarization-regulating effects of AL were verified in vitro. Suppressed NOD-like receptor thermal protein domain associated protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome activation was found in the ischemic penumbra of animal and Oxygen-Glucose Deprivation/Reoxygenation (OGD/R) cells treated with AL, as evidenced by decreasing NLRP3-inflammasome-related protein and downstream factors. After AL treatment, the anti-apoptosis effect of microglial exosomes on OGD/R primary cortical neurons was increased.

AL reduce inflammatory responses and neuron death of IS-associated models by regulating microglia polarization by the NLRP3 pathway and by affecting microglial exosomes.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords

- avicularin

- ischemic stroke

- microglial exosomes

- microglia polarization

- NLRP3

Stroke is the most common cerebrovascular disease and one of the principal causes of severe disability and death [1, 2]. Ischemic stroke (IS) is caused by an obstruction of a cerebral artery and accounts for approximately 87% of stroke cases [3, 4]. IS in humans is a heterogeneous disease and includes various subtypes in clinical studies, such as atherothrombotic infarct, lacunar infarct, cardioembolic stroke, infarct of unusual etiology, and essential cerebral infarct [5]. Although recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA) is authorized for IS treatment, only a small number of patients benefit from rtPA treatment due to the strict treatment window and the risk of hemorrhage [6]. The high disability and mortality rates of IS bring a heavy economic burden to the whole of society [7]. Therefore, it is urgent to gain a deeper understanding of IS pathogenesis.

More and more studies have suggested that inflammation is closely associated with the effects of IS [8, 9]. Microglia, a brain-resident immune cell, is a vital mediator of neuroinflammatory responses after IS [10]. During IS, microglia are activated and polarized into the toxic pro-inflammatory phenotype (M1) or the protective anti-inflammatory phenotype (M2) [11]. M1 microglia induce brain injury, inhibit neurogenesis, and interfere with neurological function by producing pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-1

Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) has a long history and has played an important role in combating IS [3]. Xixian Tongshuan Pills are made from Banxia (Pinellia ternata), Herba Siegesbeckiae, Arisaema cum Bile, and other TCM substances, and, based on our team investigation, are used to relieve hemiplegia, limb numbness, and other symptoms caused by IS. Other TCM prescriptions, mainly composed of Banxia, seem to play a therapeutic role in brain-related injuries, including relieving emotional disorders, cognitive impairment, and especially, neuroinflammation [13, 14, 15]. But, the active ingredients of Banxia for IS relief have not been clarified. Avicularin (AL), as an ingredient of Banxia, enhances cognition, and reverses inflammatory response and oxidative stress in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease [16], and decreases the secretion of inflammatory factor in neuronal cells [17], indicating that AL treatment has a positive effect on brain function. In addition, inflammatory responses and M1 polarization of macrophages are inhibited by AL [18]. We therefore began studying the effect of AL treatment on IS damage as well as its underlying mechanism.

Exosomes (30–160 nm) are produced by plasmalemma invagination and exist in body fluids [19, 20]. Emerging evidence has demonstrated that exosomes, which have ability to cross blood brain barrier and have low toxicity and immunogenicity [21], regulate neurovascular remodeling, cell apoptosis, and inflammation, after IS [22]. Exosomes derived from microglia-transferred RNAs, lipids, and soluble proteins, influence neuroprotection or injury [23]. Whether AL treatment modulates the secretion of exosomes to disturb IS progression remains to be studied.

In the present study, the effects of AL treatment on IS damage, and the underlying mechanism, were explored.

All animal experiments were carried out following the Guideline for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and authorized by the Experimental Animal Ethics Committee of Liaoning University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (No. 21000042023094). All cell lines were validated by STR and tested negative for mycoplasma. The BV2 cell is a microglia cell line derived from mice and is used widely in study of IS [24, 25]. BV2 cells (mouse microglia cells; Cat. No. iCell-m011) were obtained from iCell Bioscience Inc. (Shanghai, China) and cultured in an incubator (5% CO2, 37 °C) in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM; Servicebio, Wuhan, Hubei, China) containing 10% fetal bovine serum. Primary cortical neurons were obtained from five mice at 16 embryonic days. Embryonic day 16 mice were prepared from timed-pregnant C57BL/6J mice. The pregnant mice were euthanized with CO2. Fetuses were taken out and their brains were removed rapidly. The cerebral cortices were dissected out. After digestion with trypsin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), the neurons were cultured in Neurobasal medium supplemented with 1% B27 in plate, then cells were cultured in an incubator (5% CO2 at 37 °C). The cytarabine (10 µM; Aladdin, Shanghai, China) was added to eliminate glial cells in the next day. The frequency of half-culture solution replacement was kept every 3 days.

The cells were cultured in medium without glucose in an incubator with 95% N2 and 5% CO2 for 4 h to establish the Oxygen-Glucose Deprivation (OGD) model, as described previously by Zhou et al. [26]. Next, cells were incubated with AL (25, 50, and 100 µg/mL, Cat. No. HY-N0222; MedChemExpress, Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA) or exosome (20 µg) for 24 h under normal conditions (5% CO2, 37 °C; corresponding medium).

BV2 cells were used to established OGD model and then treated with AL (100 µg/mL, Cat. No. HY-N0222; MedChemExpress) under normal conditions. Twenty-four h after AL treatment, the supernatant was collected and centrifuged multiple times to obtain exosomes (AL-Exo). Exosomes isolated from BV2 cells without AL treatment (BV2-Exo) were regarded as contrast. Morphology and size distribution of exosomes were observed using an HT-7700 transmission electron microscope (TEM, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) and a ZetaVIEW nanoparticle tracking analyzer (NTA, PARTICLE METRIX, Munich, Germany). Western blot analysis was used to detect the markers of exosomes (CD63, CD81, and CD9).

The mice were purchased from Huachuang Sino (Taizhou, Zhejiang, China). Male C57BL/6J mice (8 weeks old) were housed in a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle environment with appropriate temperature and humidity, and given free access to food and water for 1 week of acclimation. One hundred and fifty mice were randomly assigned to five groups using a computer-generated random-number table. The grouping set in our paper included, sham group (N = 30) received sham surgery without the monofilament block and sodium carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC-Na, Cat. No.C835846; Macklin, Shanghai, China) by oral gavage, MCAO/R group (N = 30) received blood occlusion and CMC-Na by oral gavage, MCAO/R+1.25 mg/kg/day avicularin (MCAO/R+AL-L) group (N = 30) received blood occlusion and 1.25 mg/kg/day AL by oral gavage, MCAO/R+2.50 mg/kg/day avicularin (MCAO/R+AL-M) group (N = 30) received blood occlusion and 2.50 mg/kg/day AL by oral gavage, and MCAO/R+5.00 mg/kg/day avicularin (MCAO/R+AL-H) group (N = 30) received blood occlusion and 5.00 mg/kg/day AL by oral gavage.

The MCAO/R model was established as previously described and isoflurane (Shenzhen Rayward Life Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China; 3% for anesthesia induction and 2% for anesthesia maintaining) was used for anesthesia [27]. Briefly, monofilament was used to obstruct the origin of the left middle cerebral artery. One h after occlusion, the monofilament was removed to start reperfusion. Sham mice received the same surgery without the monofilament block.

AL (Cat. No. HY-N0222; MedChemExpress) was dissolved in 0.5% CMC-Na and administered by oral gavage once a day for 7 days at the doses of 1.25, 2.5, or 5 mg/kg, starting 3 h after reperfusion. The treatment time and doses of AL used in our study were determined by the procedures of a previous study [28]. Sham mice and MCAO/R mice received an equal volume of 0.5% CMC-Na by oral gavage. Twenty-four h after the last administration, mice underwent the behavioral test and were then euthanized with CO2.

The modified neurological severity score (mNSS) test was used to evaluate the neurological deficit (normal score, 0; maximum-deficit score, 18), and conducted as described in previous studies [29, 30], with slight modifications, on day 8, by observers blind to the experiment. The higher the score, the more serious the injury.

Brain samples were harvested from the sacrificed mice, frozen for 1 h and cut into slices. The brain slices were immersed in Triphenyltetrazolium Chloride (TTC, Cat. No. T8170; Solarbio, Beijing, China) and incubated for 15 min at 37 °C. With TTC, the normal tissue was stained red and the infarct-damaged tissue was white.

After the mice were euthanized with CO2 (Shenyang Jingquan Gas Plant, Shengyang,China), the brains were removed, weighed (wet weight) and then dried at 105 °C overnight to obtain the dry weight. Brain-water content (%) = (wet weight – dry weight)/wet weight

Fresh ischemic penumbra (cortex) tissue was removed from the brain, and then fixed, dehydrated, infiltrated, embedded, and cut into 5-µm slices. After dewaxing, hydration, permeabilization, and antigen retrieval, slices were incubated with TdT-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) reactive solution (Cat. No. 11684795910; Roche, Basel, Switzerland) for 60 min in the dark. After 30 min of blocking with bovine serum albumin (BSA; Cat. No. A602440-0050; Sangon Biotech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), slices were incubated with NeuN polyclonal antibody (1:50; Cat. No. 26975-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc., Rosemont, IL, USA) at 4 °C overnight. Next, they were incubated with Cy3–conjugated secondary antibody (1:200; Cat. No. SA00009-2; Proteintech Group, Inc.) for 60 min. Finally, cell nuclei were re-stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Cat. No. D106471; Aladdin) and examined with a BX53 microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

For TUNEL analysis, cell slide was made and permeabilized. The cell slide was incubated with TUNEL reactive solution for 60 min in the dark. After counterstaining with DAPI, the cell slide was photographed using a DP73 camera system (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Twenty-four h after AL treatment, the BV2 cells were collected, centrifuged, and resuspended in phosphate buffered saline (Cat. No. B548117; Sangon Biotech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd.). CD86 antibody conjugated with phycoerythrin fluorescent dye (Cat. No. PE-65068; Proteintech Group, Inc.) and CD206 antibody conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (Cat. No. 141703; FITC; Biolegend, San Diego, CA, USA) were added to cells. The co-incubation lasted for 30 min in the dark. A NovoCyte flow cytometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was used for detection.

Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) assay was performed to analyze the death rate of primary neurons using an LDH assay kit according to manufacturer’s instructions. The kit was purchased from Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute (Cat. No. A020; Nanjing, Jiangsu, China). Absorbance was measured using a microplate reader ELX-800 (BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA).

The levels of IL-1

Tissue slices were treated for double immunofluorescence. After antigen retrieval and sealing, slices were incubated with the following primary antibodies (1:100) at 4 °C overnight: Ionized calcium binding adapter molecule (IBA1) antibody (Cat. No. Ab283319; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), CD86 antibody (Cat. No. DF6332; Affinity, Changzhou, Zhejiang, China), CD206 antibody (Cat. No. DF4149; Affinity), and NOD-like receptor thermal protein domain associated protein 3 (NLRP3) antibody (Cat. No. DF7438; Affinity). After being rinsed, slices were incubated with FITC-conjugated or Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody (1:200; Cat. No. SA00003-2/SA00009-1; Proteintech Group, Inc.) for 90 min. The cell slide was used to measure the polarization of microglia, and permeated with tritonX-100 (Cat. No. ST795; Beyotime) for 30 min then blocked with BSA for 15 min. After incubation with INOS antibody (1:100; Cat. No. AF0199; Affinity) or Arginase 1 (ARG1) antibody (1: 100; Cat. No. DF6657; Affinity), the cell slide was incubated with Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody (1:200; Cat. No. SA00009-2; Proteintech Group, Inc.) for 60 min. All slices and slides were redyed by DAPI and photographed using a BX53 microscope.

The protein was obtained by radio-immunoprecipitation-assay lysis buffer (Cat. No. PR20001; Proteintech Group, Inc.), and its concentration was measured using the BCA protein quantitative kit (Cat. No. PK10026; Proteintech Group, Inc.). Next, proteins were separated by gel electrophoresis and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Cat. No. LC2005; Thermo Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). After incubation in blocking buffer (Cat. No. PR20011; Proteintech Group, Inc.), the membranes were blotted using the following primary antibody at 4 °C overnight: caspase 3 antibody (1:1000; Cat. No. AF6311; Affinity); cleaved caspase 3 antibody (1:1000; Cat. No. AF7022; Affinity); NLRP3 antibody (1:1000; Cat. No. DF7438; Affinity); cleaved caspase 1 antibody (1:1000; Cat. No. AF4005; Affinity); PYD And CARD Domain Containing (ASC) antibody (1:1000; Cat. No. DF6304; Affinity); CD63 antibody (1:1000; Cat. No. AF5117; Affinity); CD81 antibody (1:1000; Cat. No. DF2306; Affinity); CD9 antibody (1:1000; Cat. No. AF5139; Affinity); and

GraphPad Prism 9.0.0 (Dotmatics, Boston, MA, USA) was used to perform statistical analysis and differences were analyzed using ordinary one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Tukey’s multiple comparisons test or Kruskal-Wallis test. Data followed by the Dunn’s multiple comparisons test were shown as mean

To confirm whether AL treatment ameliorated IS injury, the MCAO/R mouse model was established and the pharmacological effects of AL treatment were evaluated. As shown in Fig. 1A, after the MCAO/R procedure, an increase in mNSS in the model group (surgery only) indicated significant ischemic injury (p

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. AL treatment markedly decreased ischemic lesion in MCAO/R mice. (A) After seven days of AL treatment, the MCAO/R mice was accepted behavioral test to evaluate degree of nerve damage. Brain samples were harvested from the sacrificed and used for the following experiments. (B) TTC staining was conducted to measure the cerebral infarct volume. (C) The wet weight and dry weight of brain tissue of mice were weighed to calculate brain water content. (D) Neuronal apoptosis of ischemic penumbra was detected by using double immunofluorescence (NeuN: red; TUNEL: green; DAPI: blue; Bars = 50 µm). (E) Western blotting analysis was used to measure the protein expression of total caspase 3 and cleaved caspase 3. (F) IL-6 and TNF-

In order to elucidate the effect of AL on microglia polarization against a background of ischemia, polarization markers were detected using immunofluorescence. After IS, the numbers of CD86-marked M1 microglia and CD206-marked M2 microglia were higher those in sham mice (p

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. AL regulated microglial polarization after MCAO/R. Double immunofluorescence (IBA1: red; CD86 or CD206: green; DAPI: blue; The images in the dashed rectangles are amplified on the right = 50 µm) was used to assay the microglial polarization in ischemic penumbra of MCAO/R treated with AL or untreated (n = 6, *p

Considering the above results, we described an important role for AL in suppressing inflammation. Next, the pathway mediating the function of AL was explored. Double immunostaining results showed that the NLRP3 inflammasome was activated in the cortex of MCAO/R mice but not in cortex of the sham group mice (p

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. AL treatment interfered with the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome after MCAO/R. (A) Representative double immunofluorescence staining for IBA1 (red) and NLRP3 (green). The nucleus was stained blue (Bars = 50 µm). The images in the solid rectangles are magnified representative cell. (B) The protein expression of NLRP3, cleaved caspase 1 and ASC in ischemic penumbra of mice was measured by Western blot analysis. (C) IL-1

To verify that the inflammatory response was mediated by polarized microglia, an OGD/R model was established in vitro (Fig. 4A). ELISA results showed that the levels of IL-6 and TNF-

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. AL treatment ameliorated the inflammatory response of OGD/R BV2 cells by affecting cell polarization. (A) OGD/R model was established to detect the effect of AL on microglial polarization in vitro. (B) ELISA was used to measure the levels of IL-6 and TNF-

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. AL affected cell polarization of OGD/R BV2 cells. Flow cytometry was conducted to assay the expression of CD86 and CD206. Data are showed as mean

We examined whether NLRP3 was a mediator of AL in inflammation intervention. The expression of NLRP3-inflammasome-related protein was detected by Western blot analysis. As shown in Fig. 6A (the original figures of Western Blot can be found in the Supplementary Materials-original western blot images-Fig6), OGD/R upregulated NLRP3, cleaved caspase 1 and ASC protein levels (p

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6. AL inhibited NLRP3 pathway in vitro. (A) NLRP3, cleaved caspase 1 and ASC protein expression in BV2 cells was measured by western blotting analysis. (B) Downstream factors (IL-1

Microglial exosomes are known to play an important role under ischemic conditions. However, the question of whether AL treatment affected the size or function of exosomes had not been studied, so our study investigated this issue (Fig. 7A). As shown in Fig. 7B,C, the microglial exosomes were observed using a transmission electron microscope and their size was measured by nanoparticle-tracking analysis. In the OGD/R condition, the average diameters of AL-treated cells and control cells were 156.9 and 157.4 nm, respectively, which were not significantly different. Western blot analysis showed that exosomes derived from cells co-expressed CD63, CD81, and CD9 (Fig. 7D, the original figures of Western Blot can be found in the Supplementary Materials-original western blot images-Fig7), which are all recognized as representative markers of exosomes. These results suggest that AL treatment appears to have no effect on the appearance of exosomes.

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7. Exosomes derived from AL-treated OGD/R BV2 cells reduced neuron death. (A) After OGD/R, the microglial exosomes were obtained with and without AL treatment. These exosomes were used to culture primary cortical neurons that had undergone OGD processing. Characterization of microglial exosomes was assayed by TEM (Bars = 1 µm) (B), NTA (C) and Western blot analysis (D). (E) Neuronal death was evaluated by the measurement of LDH. (F) Representative images of TUNEL staining (green) for primary cortical neurons. The nucleus was stained blue (Bars = 50 µm). Results are showed as mean

Next, primary cortical neurons were used to detected exosome function. OGD/R-treated cells released more LDH than did control cells (p

In the present study we investigated the effect of AL on inflammatory response and its mechanism. Our findings indicated that AL reversed motor-behavior deficits and restrained neuronal death that had been induced by ischemia/reperfusion. The underlying mechanism (weakening neuroinflammation by AL) was closely connected to microglia polarization by regulation of the NLRP3 pathway. It is noteworthy that exosomes derived from microglia that were treated with AL reduced neuron death. These results are expected to provide novel insights into the mechanisms of AL for the treatment of IS.

Stroke may be a manifestation of hematological disorders. Considering different inducements, IS and other hematological diseases have different outcomes, treatment methods, and recurrence risks [31]. Due to the limitations of treatment methods, IS has attracted attention and this has led to the development of several animal models [32]. Among these is the MCAO/R procedure, which involves blocking the cerebral blood supply causing ischemia. It is currently the most widely recognized and used model [33]. Neurological-movement deficits, infarct size, brain edema, and neuronal cell death are considered to be increased in IS [34, 35, 36]. AL treatment induced motor recovery, decreased pathological manifestations of ischemia, and inhibited neuronal apoptosis. Mounting evidence had confirmed that AL treatment reverses depressive-like behaviors and AD-like behaviors in animal models [16, 28], and our results were consistent with the previous findings that AL relieved neurological-movement deficits.

The anti-inflammatory effect of AL treatment in various diseases, including neuroinflammation, osteoarthritis, and hepatic injury, has been reported previously [17, 37, 38, 39]. In the present study, the inflammatory response was reduced in vivo and in vitro after AL treatment. Inflammation and polarization of microglia are believed to be relevant during the development of IS damage. After IS, microglia are activated and polarized into the M1 or M2 phenotype. CD86- or INOS-marked M1 microglia trigger neuroinflammation by releasing inflammatory factors (TNF-

The NLRP3 inflammasome, as a crucial component of innate immunity, contributes to inflammation and cell death by activating caspase-1 and by releasing IL-1

Increasing evidence has indicated that the exosome, as a new means of neurovascular communication, acts as a critical mediator in physiological and pathological processes of the central nervous system [49]. Exosomes from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells, plasma, neurons, and microglia have been found that had neuroprotective and angiogenesis-promoting effects after IS [50, 51, 52, 53]. While, microglia exosomes obtained from OGD/R condition exhibited no effect on neuronal apoptosis or aggravated neuronal apoptosis, increased brain microvascular endothelial cells integrity impairment, and induced further damage of neurite structure [53, 54]. Exosomes contain proteins, RNAs, and lipids [55, 56], and some microRNAs were identified as differentially expressed in microglia after OGD/R [54] and in M1-phenotype BV2 cells [57]. Therefore, we speculated that some RNAs, proteins, and lipids that are contained in exosomes secreted by M1 microglia, induced neuron death. In other words, the protective effect of exosomes from microglia seems to be weakened or even reversed by the low-glucose and low-oxygen condition. In the current study, we separated the exosomes secreted by OGD/R BV2 cells, and found that exosomes from AL-treated cells significantly decreased neuron death. We propose that AL ameliorates IS damage by attenuating M1 polarization and enhancing M2 polarization through weakening the activation of the NLRP3 pathway. Subsequently, AL treatment affects the exosomes derived from microglia, that the exosomes disturbed neuron death in IS. In other words, AL ameliorates IS damage, not only by changing microglia polarization, but also by affecting exosomes from microglia via the NLRP3 pathway. Some issues remain unclear, for example, the role of exosomes obtained from AL-treated BV2 cells in inflammation was not addressed in the present study, but needs further research.

AL treatment ameliorates ischemic stroke by attenuating M1 polarization and enhancing M2 polarization by weakening activation of the NLRP3 pathway. Exosomes derived from AL-treated microglia reduced neuron death after IS. Thus, AL may have great potential for IS treatment. In the future we will investigate the role of exosomes obtained from AL-treated BV2 cells in inflammation.

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

JZ: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing - original draft; JL: Investigation, Methodology; YY: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing - review & editing; YS: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing - review & editing. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

All animal experiments were carried out following the Guideline for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and authorized by the Experimental Animal Ethics Committee of Liaoning University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (No. 21000042023094).

Not applicable.

The Project was supported by the Open fund of Key Laboratory of Ministry of Education for TCM Viscera-State Theory and Applications, Liaoning University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (grant number ZYZX2207).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/j.jin2311196.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.