1 Department of Neurology, The Affiliated Nanhua Hospital, Hengyang Medical School, University of South China, 421001 Hengyang, Hunan, China

2 Department of Intensive Care Unit, The Affiliated Nanhua Hospital, Hengyang Medical School, University of South China, 421001 Hengyang, Hunan, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Luteolin is a natural flavonoid and its neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects have been confirmed to mitigate neurodegeneration. Despite these findings, the underlying mechanisms responsible for these effects remain unclear. Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) is widely distributed in microglia and plays a pivotal role in neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration. Here studies are outlined that aimed at determining the mechanisms responsible for the anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective actions of luteolin using a rodent model of Parkinson's disease (PD) and specifically focusing on the role of TLR4 in this process.

The mouse model of PD used in this experiment was established through a single injection of lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Mice were then subsequently randomly allocated to either the luteolin or vehicle-treated group, then motor performance and dopaminergic neuronal injury were evaluated. BV2 microglial cells were treated with luteolin or vehicle saline prior to LPS challenge. MRNA expression of microglial specific marker ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1 (IBA-1) and M1/M2 polarization markers, as well as the abundance of indicated pro-inflammatory cytokines in the mesencephalic tissue and BV2 were quantified by real time-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA), respectively. Cell viability and apoptosis of neuron-like PC12 cell line co-cultured with BV2 were detected. TLR4 RNA transcript and protein abundance in mesencephalic tissue and BV2 cells were detected. Nuclear factor kappa-gene binding (NF-κB) p65 subunit phosphorylation both in vitro and in vivo was evaluated by immunoblotting.

Luteolin treatment induced functional improvements and alleviated dopaminergic neuronal loss in the PD model. Luteolin inhibited apoptosis and promoted cell survival in PC12 cells. Luteolin treatment shifted microglial M1/M2 polarization towards an anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype both in vitro and in vivo. Finally, it was found that luteolin treatment significantly downregulated both TLR4 mRNA and protein expression as well as restraining NF-κB p65 subunit phosphorylation.

Luteolin restrained dopaminergic degeneration in vitro and in vivo by blocking TLR4-mediated neuroinflammation.

Keywords

- Parkinson's disease

- luteolin

- M1/M2 polarization

- neuroinflammation

- toll like receptor 4

The clinical features of Parkinson’s disease (PD) is rest tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia and disturbance in balance. The pathological alteration of PD is gradually reduction of nigral dopaminergic neurons [1]. The current therapeutic cornerstone of PD is dopamine replacement therapy. However, dopamine replacement therapy is only effective in temporarily attenuating disease symptoms and symptoms eventually worsen. Moreover, extended dopamine use is associated with several side effects [2]. Therefore, emerging PD studies generally focus on phytochemicals for long-term disease symptom modification.

Luteolin is a natural polyphenolic flavonoid compound present in several fruits and vegetables, like chrysanthemum, Perilla species, beets and carrots [3]. The neuroprotective potential of luteolin has been demonstrated in a variety of neurological disorders [4] and previous study has shown that luteolin can reduce neuronal death and cerebral edema in a rodent model of traumatic brain injury [5]. Luteolin also functions in a neuroprotective role in the cognitive dysfunction displayed in an experimental model of epilepsy by inhibiting inflammation and reducing oxidative stress [6]. Depressive-like mice treated with luteolin also show improvement in anxiety behavior [7]. Despite this body of evidence, the exact role and mechanism of luteolin’s actions in PD remain unclear.

As the major immune effector cells in the brain. This cell type plays a vital role in central nervous system (CNS) homeostasis, including immune regulation, debris removal and damage repair [8]. Microglia are most dense in the substantia nigra and this specific distribution lays an anatomical foundation for microglia as an important player in PD pathogenesis. Microglia are subdivided into anti-inflammatory M2 and pro-inflammatory M1 phenotypes. Upon stimulation in response to trauma, foreign bodies, infection, microglia are promptly activated into the M1 type and its morphology changes with branch protrusions becoming thicker and cell bodies becoming larger [9]. Coordinately, microglia release a large number of inflammatory factors, reactive oxygen species, nitric oxide and superoxide glutamate to both kill pathogenic microorganisms and recruit additional microglia to the lesion site. This activity causes an inflammatory reaction, therefore the M1-type microglia hyperactivation is viewed as a protective reaction for the brain; however, over activation of microglia causes neuronal damage [10].

Activation of microglia may be an initiating factor for Parkinson’s disease. Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) is ubiquitously distributed in the brain, mostly in microglia and astrocytes. It is the most important pattern recognition receptor expressed in microglia and plays an essential part in inflammatory actions and regulating innate immune [11]. TLR4 recognizes several damage-associated molecular patterns such as heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) and high mobility group box 1 protein (HMGB1) and this both activates microglia and triggers an immune inflammatory cascade [12]. A pre-clinical study has demonstrated that TLR4 activity is related with neuroinflammation and neuronal injury [13]. Clinical data has also confirmed that the abundance of TLR4 in PD patients is significantly elevated and that this effect is closely related to PD progression [14, 15].

This study focused on efforts investigating the therapeutic actions of luteolin in both a rodent model of PD and cultured microglial cells. Based on our observations, it is speculated that the anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective actions of luteolin are linked with its ability for limiting TLR4 signaling.

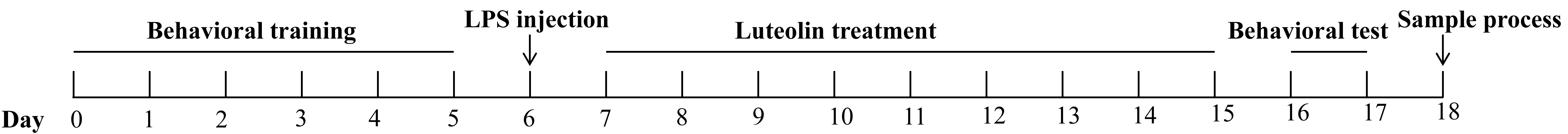

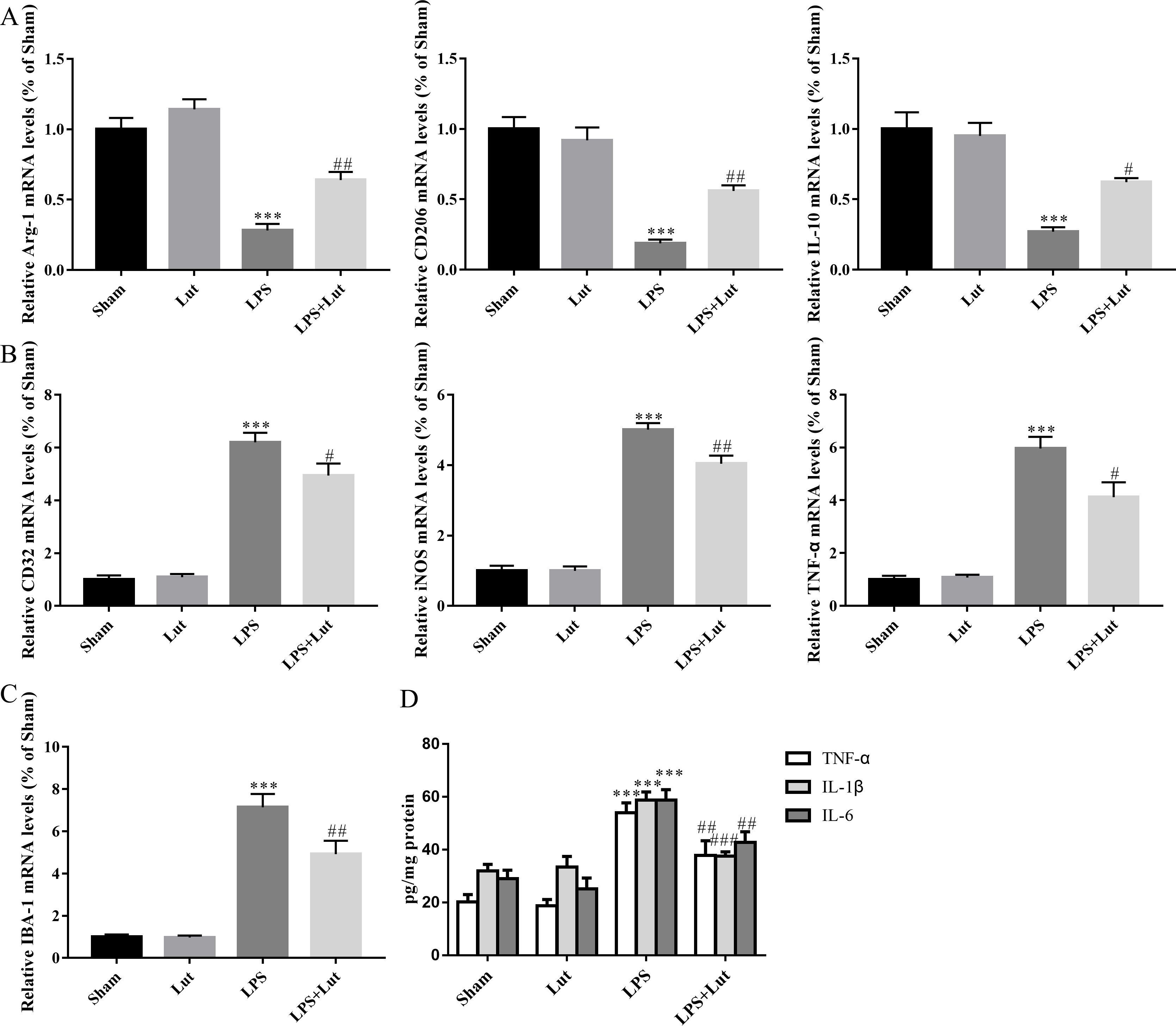

All animal experiments were approved by the Affiliated Nanhua Hospital (2024-KY-059). C57BL/6 mice (20–22 g) aged 6–8 weeks were kept with free access to water and food. Mice were trained to adapt a behavioral device for five consecutive days and mice that exhibited poor motor ability in this adjustment were not included in further study. A total of 40 animals were enrolled in this experiment and randomly allocated to each group. On day 6, mice were anesthetized with a mixture of xylazine (7361-61-7; Merck, Rahway, NJ, USA) (10 mg/kg, i.p.) and ketamine (H20023609; Jiuxu Pharmaceutical Co., LTD, Jinhua, Zhejiang, China) (90 mg/kg, i.p.). Following this, mice were injected with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (5 µg dissolved in 2 µL PBS, C0221A, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) or saline vehicle following stereotaxic coordinates measured from the bregma (Lateral: 1.3 mm; Posterior: 2.8 mm; Ventral to the surface of the dura mater: 4.5 mm). The needle was retained in the left side of the substantia nigra for a period of 10 minutes. The day after LPS injection, mice were intra-peritoneally injected with 40 mg/kg/d luteolin (Catalog: L409168; Aladdin, Shanghai, China), or saline for consecutive 9 days. Subsequently, mice were subjected to behavioral tests to evaluate motor performance on days 16 and 17. Afterward, mice were sacrificed by decapitation, and samples were collected for further analysis. The procedure is given in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The schedule used in this study. LPS, lipopolysaccharide.

BV2 microglia or PC12 neuron-like cells were purchased from Procell Life Science & Technology (Wuhan, Hubei, China) and cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM, Gibco, Anaheim, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% streptomycin/penicillin. All cell lines were validated and tested negative for mycoplasma contamination. BV2 and PC12 were both cultured in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C. BV2 were pretreated with luteolin (40 µM) or saline solution for 3 h after which BV2 were challenged with either LPS (1 µg/mL) or saline (control) for 12 h. For establishing the indirect co-culture system, PC12 was incubated in a 24-well plate for 48 h, BV2 was then transferred to a 0.4 µm pore-sized Transwell insert and co-cultured with PC12 (PC12:BV2 = 2:1) for another 48 h.

The animals were subjected to rotarod test to examine the strength and coordination. Each mouse was placed on an accelerated rotating rod (30 revolutions per minute) and the latency period to fall from the rod was recorded. If animal did not fall from the rod within 300 seconds, a maximum of 300 seconds was recorded. Each experiment was repeated three times and the mean value was calculated.

A ball wrapped with gauze was fixed on a rough rod (diameter: 0.8 cm; Height: 60 cm). Mice were placed on the ball with its head vertically up. The time it took to completely turn its head downward was recorded as T-turn, and the time it took to climb down to the ground was recorded as T-D. If the mouse fell off the pole, the data was not recorded. When mice stayed on the pole for more than 120 seconds, a maximum value of 120 seconds was recorded.

Animal were transcardially perfused with saline followed by infusion of 4% paraformaldehyde through the left ventricle. Following this, the brain tissue was dissected from the skull, and tissue was placed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) and left overnight at 4 °C, after which the brain tissues were preserved in 30% sucrose solution until the tissue sank. The fixed tissue was sliced using a sliding microtome and brain sections were rinsed and subsequently incubated overnight with primary antibodies (anti-tyrosine hydroxy lase, 1:400; Abcam, Cambridge, UK, cat: ab75875). For immunohistochemistry, sections were incubated with anti-tyrosine hydroxylase (1:400; Abcam, Cambridge, UK, cat: ab75875), followed by enzyme-conjugate IgG (1:50; Beyotime, Shanghai, China) secondary antibodies.

For immunofluorescence, BV2 was incubated with primary antibody against TLR4 (1:100; Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX, USA, cat: sc-293072). After several washings, cells were incubated with goat anti-mouse secondary antibodies CY3 (1:8000; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) in a dark room. The photos were taken using a confocal fluorescence microscope (Leica, Heidelberg, Germany). Immunohistochemistry (IHC) stained cells were examined using a brightfield microscope (Leica, Heidelberg, Germany).

Appropriate amounts of tissue were exhaustively chopped and homogenized.

Following this, tissues were then transferred into a centrifuge tube, and 3 mL of

10% sodium carbonate solution and 10 mL ethyl acetate were added to the tube.

Tissues were subsequently homogenized by shaking for 10 min at 4 °C. After

centrifugation (6000 r/min for 10 min), the upper layer organic phase was

transferred into a pear-shaped bottle and then subjected to rotary evaporation to

dry at 40 °C. The residue was dissolved in 1 mL 50% acetonitrile solution and

this solution was cooled for 30 min and centrifuged at 16,000 r/min for 5 min. An

appropriate amount of the supernatant was filtered through a 0.22 µm

membrane and then analyzed by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). The devices used in this study are a

Waters Acuity UPLC liquid chromatography (Waters, Milford, MA,

USA), an AB SCIEX 5500 Qtrap-MS mass spectrography

(AB SCIEX, Framingham, MA, USA), and an

Acquity UPLC HSS T3 chromatographic column (2.1 µm

Trizol reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was applied to extract total RNA from BV2 microglial cells or mesencephalic tissue. A PrimeScript RT reagent kit (Takara, Kusatsu, Japan) was then applied to reverse transcribed RNA into cDNA. RT-qPCR was performed using a 7300 Plus Real-time PCR System (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) and an SYBR Green kit (Takara, Japan). Thermocycling was conducted using the following conditions: Denaturation at 95 °C for 15 s, 40 cycles at 95 °C for 10 s, 60 °C for 30 s. Relative quantitative values were calculated using the 2–ΔΔCq method. Each 20 µL reaction mixture contained 10 µL PCR mixture, 1 µL cDNA template, 5 pmol primer, and a proper amount of water. Primers applied in this experiment are outlined in Table 1.

| Target gene | Forward primer sequence | Reverse primer sequence |

| iNOS | GCAGAATGTGACCATCATGG | ACAACCTTGGTGTTGAAGGC |

| CD32 | AATCCTGCCGTTCCTACTGATC | GTGTCACCGTGTCTTCCTTGAG |

| TNF- |

GTAGCCCACGTCGTAGCAAA | CCCTTCTCCAGCTGGGAGAC |

| Arg-1 | TCACCTGAGCTTTGATGTCG | TTCCCAAGAGTTGGGTTCAC |

| CD206 | AGTTGGGTTCTCCTGTAGCCCAA | ACTACTACCTGAGCCCACACCTGCT |

| IL-10 | CCAAGCCTTATCGGAAATGA | TTTTCACAGGGGAGAAATCG |

| TLR4 | AGTTGATCTACCAAGCCTTGAGT | GCTGGTTGTCCCAAAATCACTTT |

| IBA-1 | CGGGATCCGAGCTATGAGCCAGAGCAAG | GGAATTCCCCACCGTGTTATATCCACC |

| GAPDH | GTTTGTGATGGGTGTGAACC | TCTTCTGAGTGGCAGTGATG |

RT-qPCR, Quantitative Real-time PCR; TLR4, Toll-like receptor 4; iNOS, inducible

nitric oxide synthase; TNF-

The levels of Interleukin (IL)-6, IL-1

PC12 apoptosis when co-cultured with BV2 cells was determined by flow cytometry. PC12 were fixed and permeabilized, cells were subsequently stained with propidium iodide and Annexin (AP101, Multi Sciences, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China) following the manufacturer’s manual. Stained cell preparations were run and analyzed on a flow cytometer (CytoFLEX, Beckman, Pasadena, CA, USA).

Cells were seeded into a 96-well plate at 1

Radio immunoprecipitation assay (RIPA, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) buffer

containing Phenylmethanesul fonyl fluoride (PMSF) was applied to homogenize

tissues and cells. Proteins were resolved on 10% liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (SDS-PAGE), and subsequently

transferred to the polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane. After blocking for 1

hr, membranes were incubated with primary antibody TLR4 (1:100; Santa Cruz, USA,

cat: sc-293072), phospho-nuclear factor kappa-gene binding (NF-

All data presented are expressed as mean

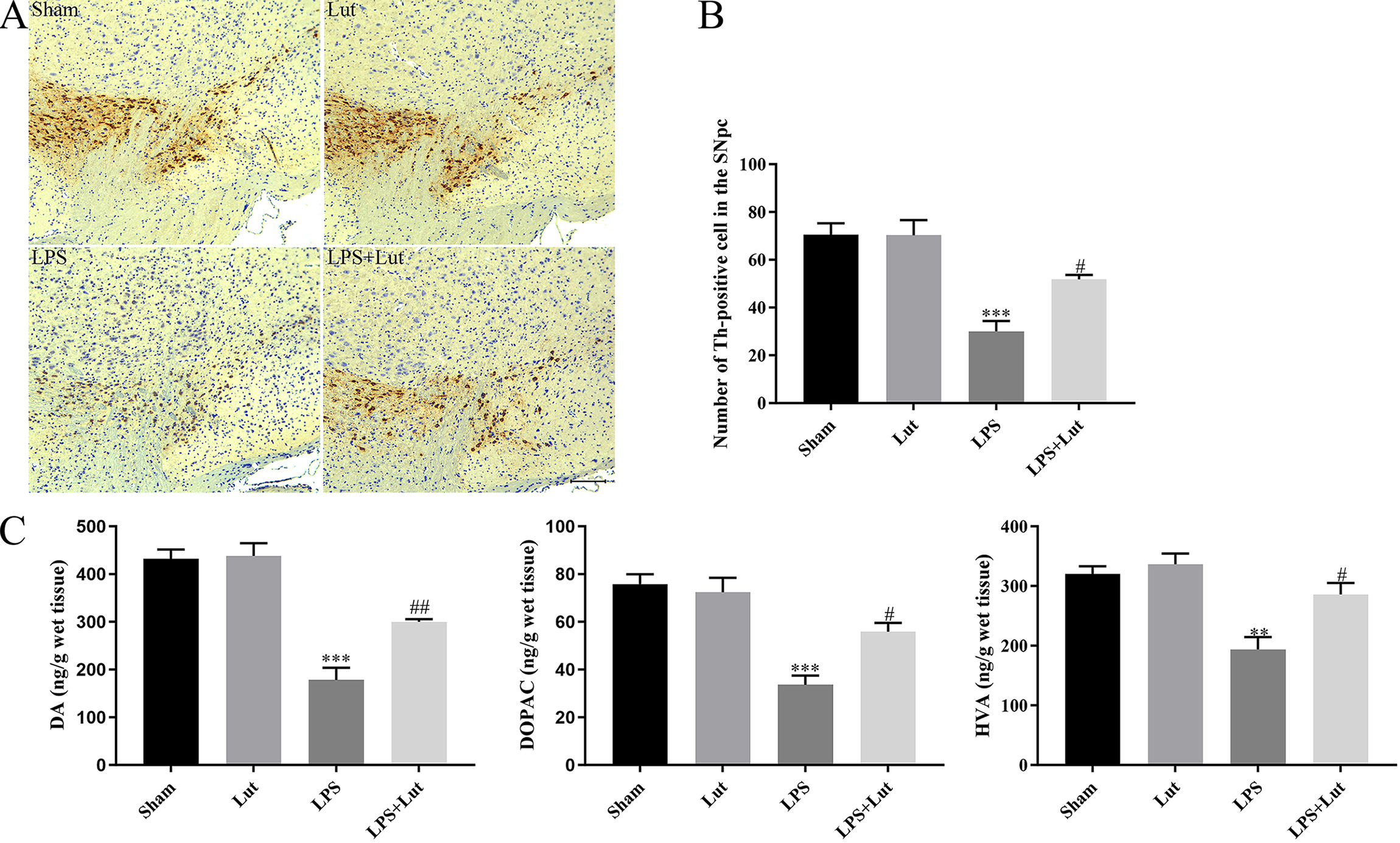

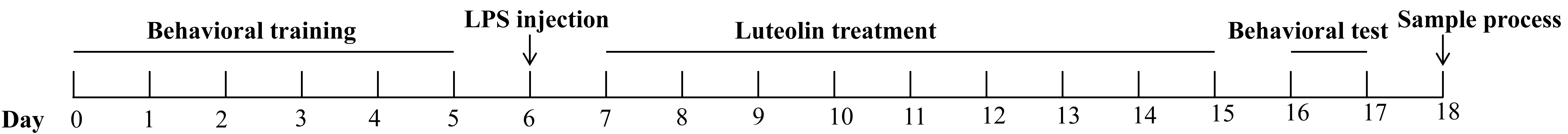

To assess the neuroprotective responses of luteolin in the outlined PD model, we

counted the number of Th positive cells in the substantia nigra (SN) using

immunohistochemical staining (Fig. 2A). We found that LPS injection lead to a

remarkable decrease of dopaminergic neurons in the SN (p

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Luteolin mitigates LPS-induced neuronal injury in the

nigrostriatal system of the PD mouse model. (A) Representative

immunohistochemical staining for tyrosine hydroxylase in the SN. Scale bar = 100

µm. (B) Th positive cells number within the SN was examined. (C) Abundance

of DA, HVA, and DOPAC in the striatum measured by LC-MS/MS. N = 5 per group.

**p

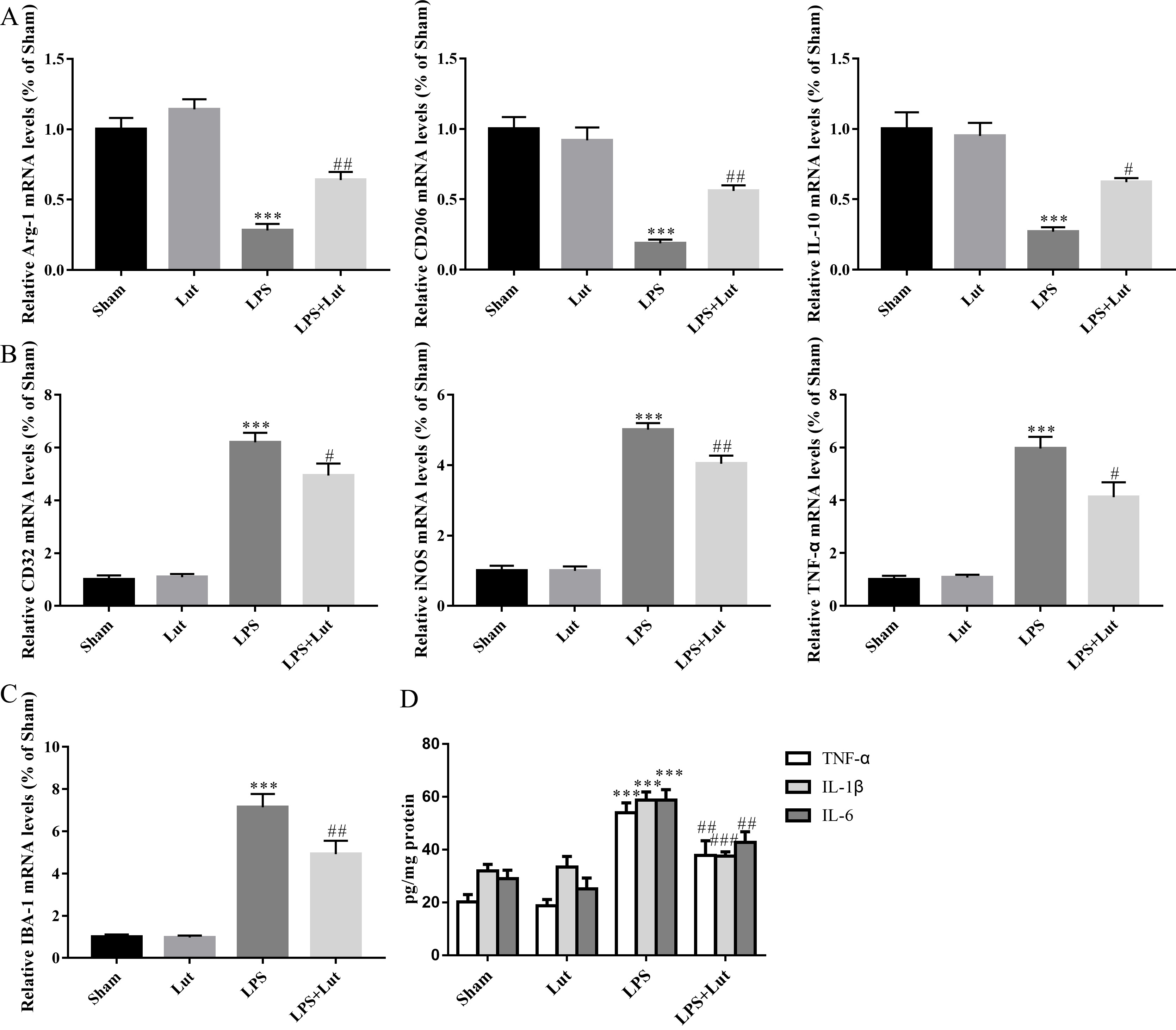

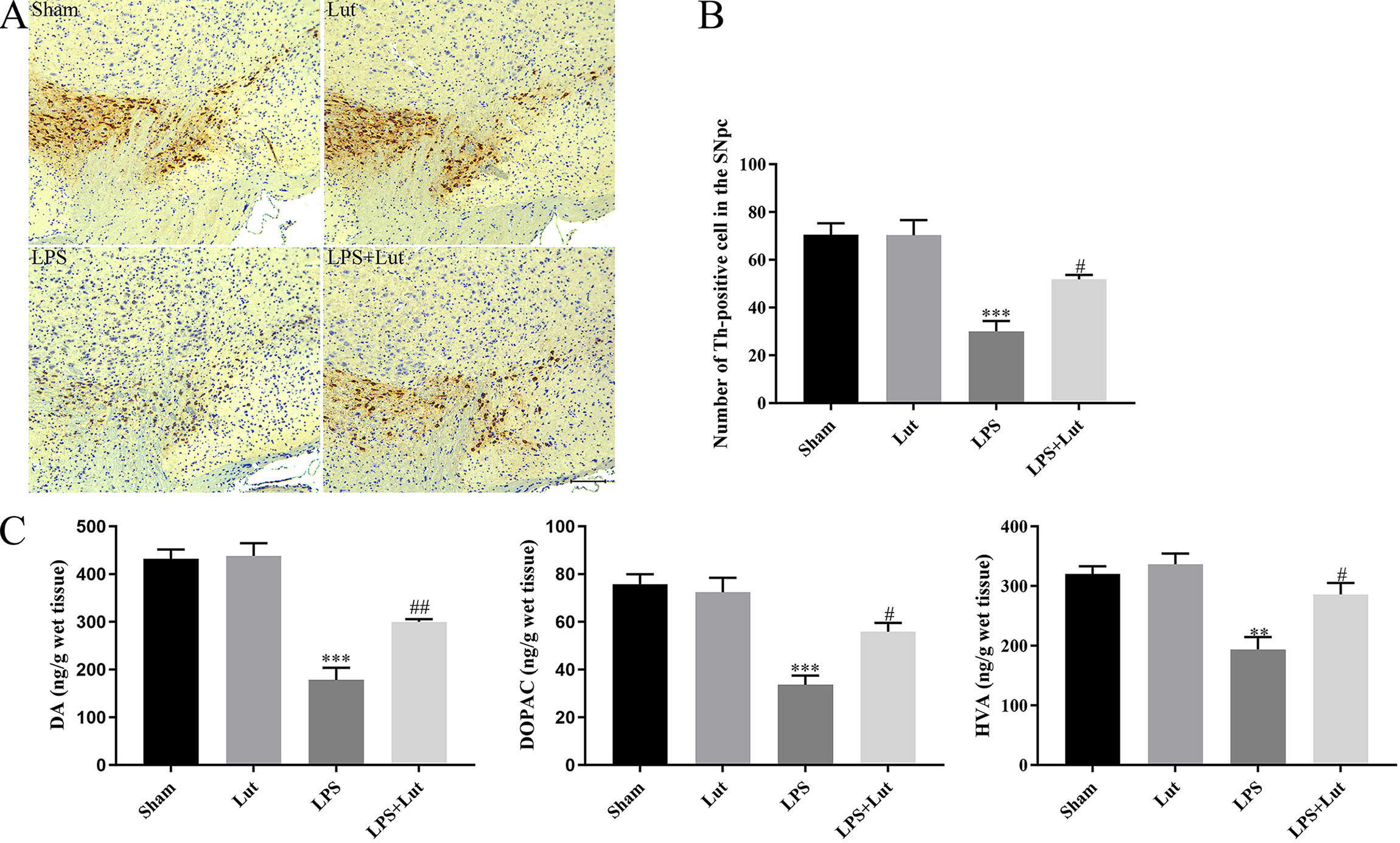

Mice were subjected to pole and rotarod tests to assess grip strength and

coordination, respectively. LPS injection showed a poorer motor ability in the

pole test (T-turn: p

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Luteolin improves motor performance in the PD model. (A) The

time for each mouse to turn its head completely downward (T-turn) and climb down

to the ground (T-D) was recorded in the pole test. (B) The latency to fall off

the rotating rod was recorded in the rotarod test. N = 10 per group.

***p

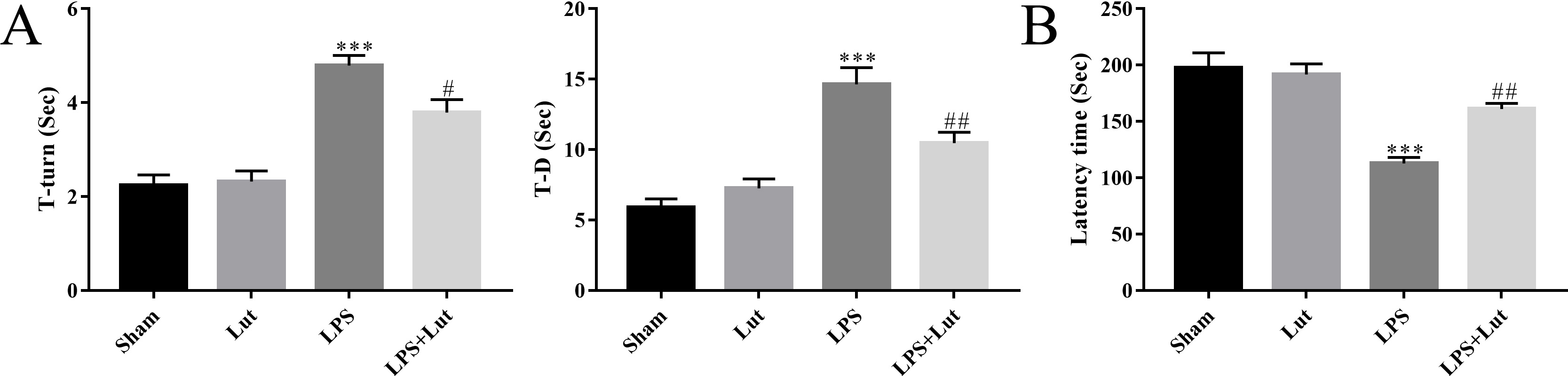

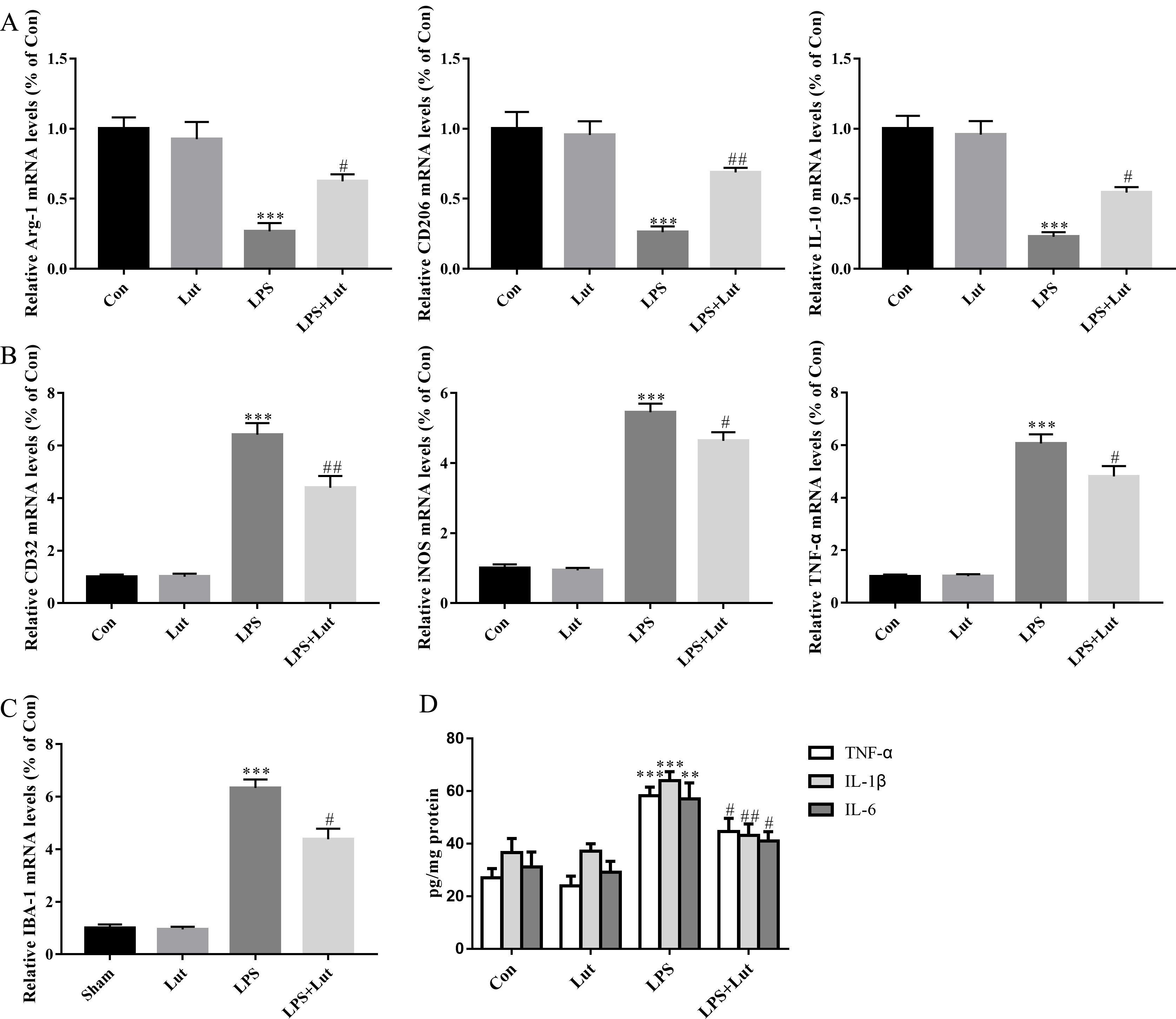

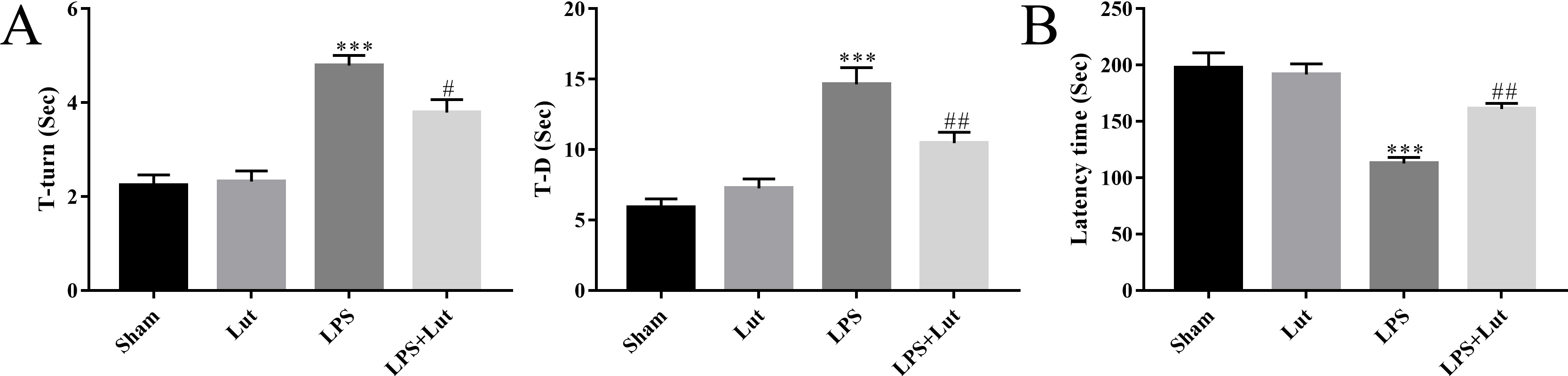

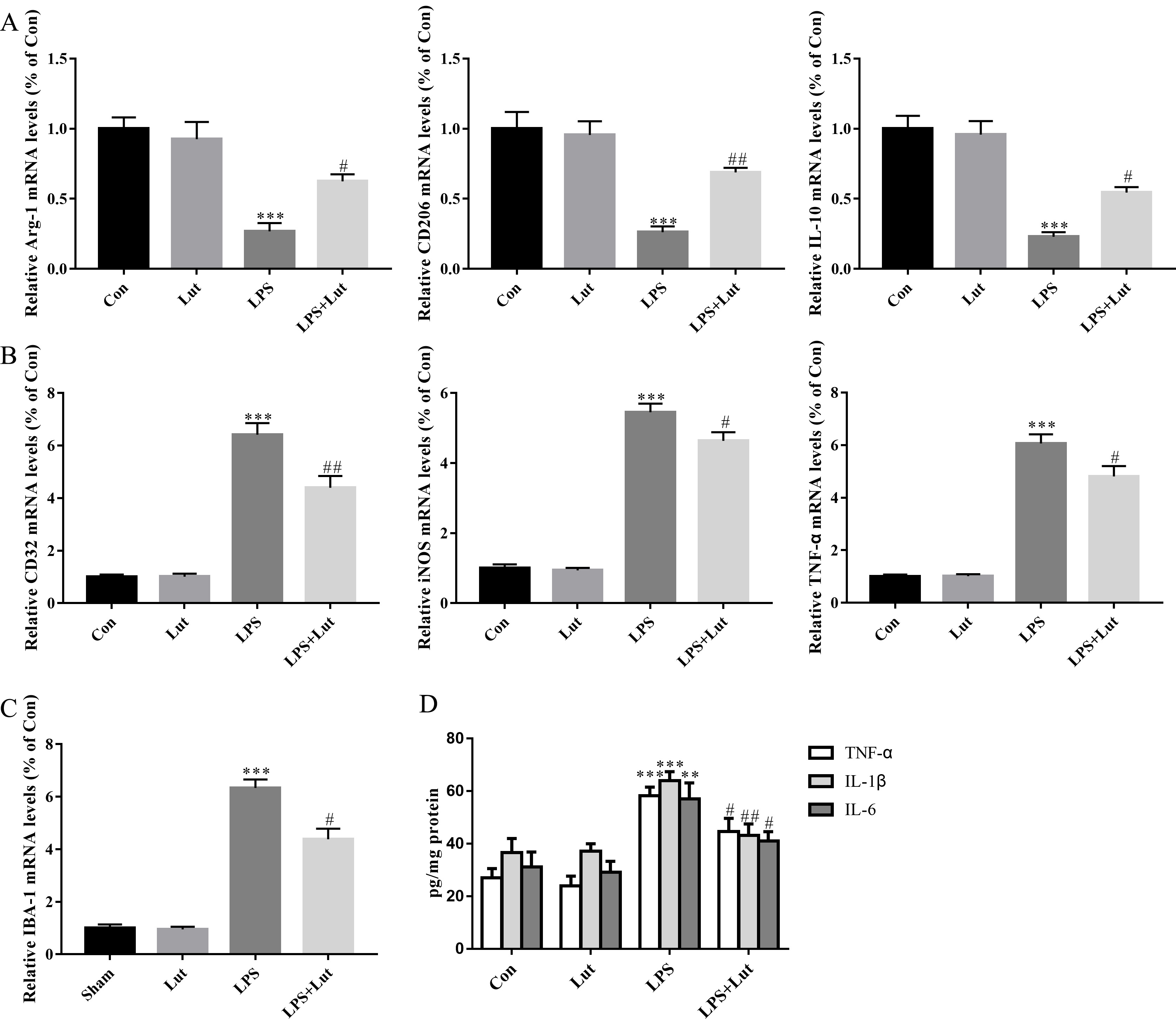

Microglial polarization is vital for neuroinflammation and neuronal degeneration

in PD. Thus, we measured relative mRNA abundance of several M1/M2 polarization

markers in the midbrain using RT-qPCR. LPS injection reduced anti-inflammatory M2

phenotype markers like Arginase-1 (Arg-1) (p

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Luteolin shifts M1/M2 polarization and inhibits the release of

pro-inflammatory cytokines in the PD model. (A) Relative mRNA abundance of

microglial M2 polarization phenotypic markers Arg-1, CD206, and

IL-10. (B) Relative mRNA abundance of microglial M1 polarization markers

CD32, iNOS, and TNF-

We next measured the abundance of indicated pro-inflammatory cytokines in the

midbrain using ELISA. LPS injection resulted in an elevated level of

pro-inflammatory cytokine release in the midbrain; specifically, IL-6 (p

We next measured relative mRNA levels of M1/M2 phenotypic markers in BV2. As

expected, following LPS challenge, BV2 cells exhibited decreased levels of the M2

markers Arg-1 (p

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Luteolin shifts microglial M1/M2 polarization and limited the

release of pro-inflammatory cytokines in BV2 microglia cells challenged with

LPS. (A) Relative mRNA abundance of microglial M2 phenotypic markers

Arg-1, CD206, and IL-10. (B) Relative mRNA abundance

of microglial M1 phenotypic markers CD32, iNOS, and

TNF-

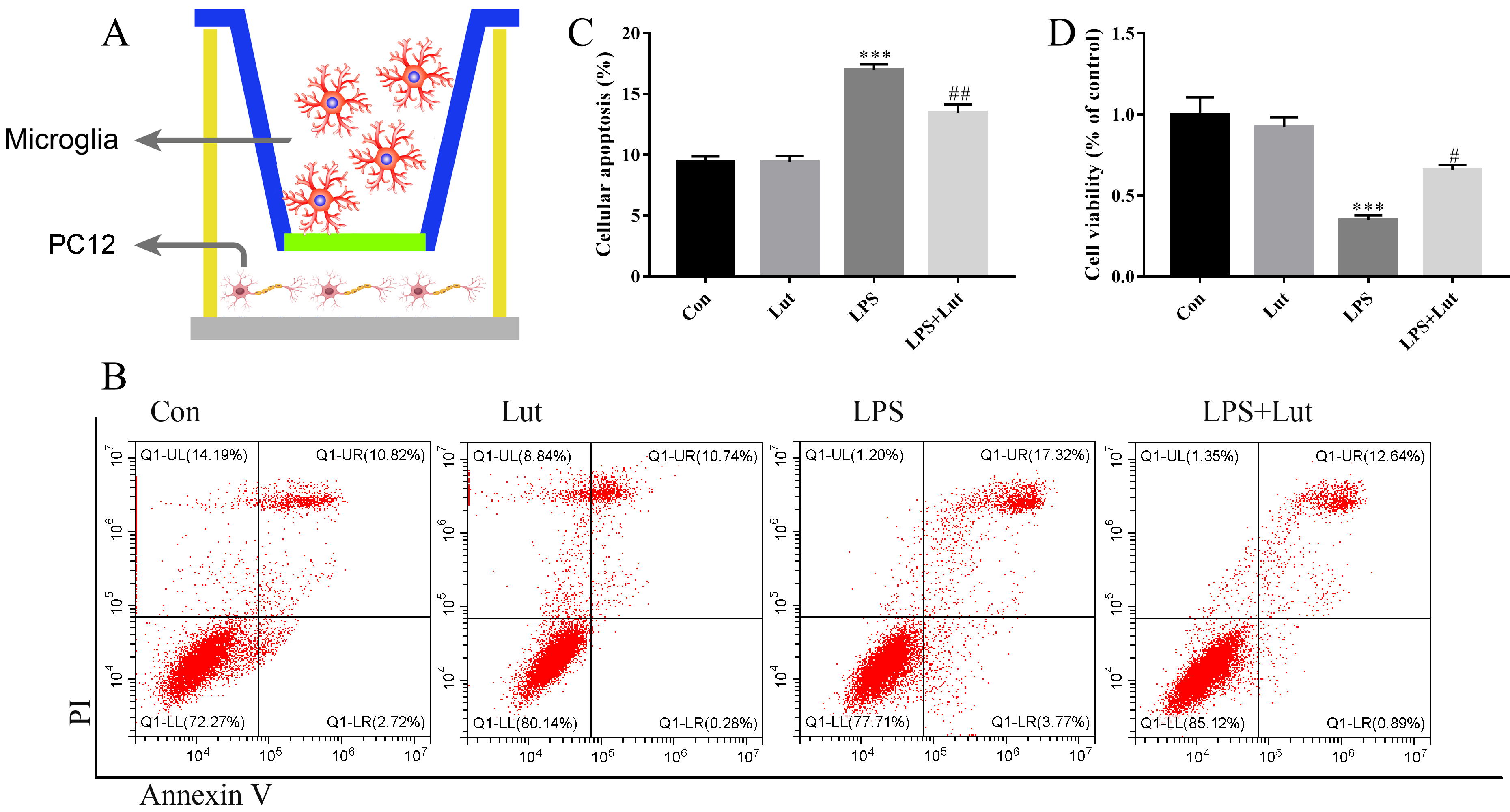

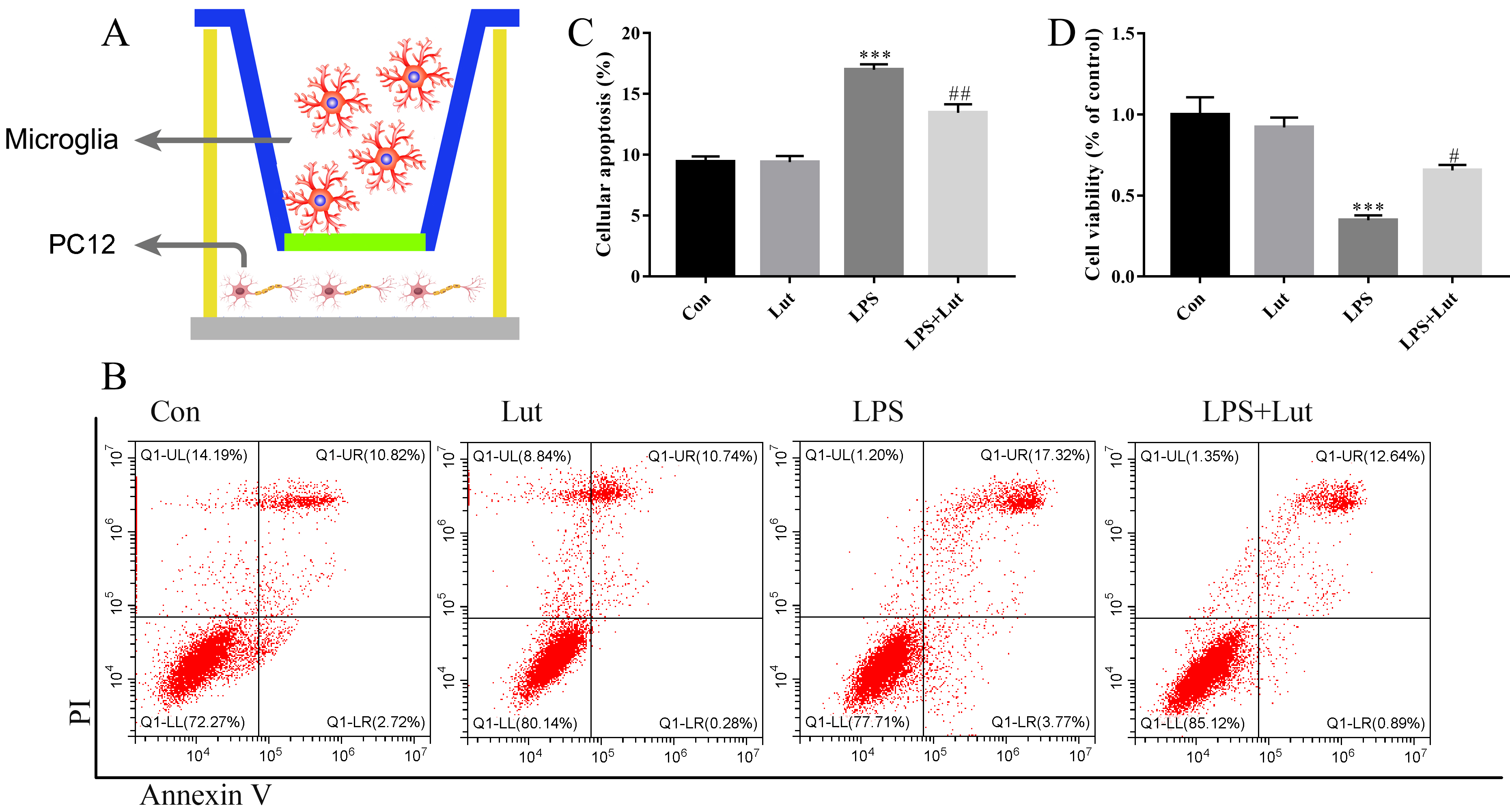

We established a microglia/neuron indirect co-culture system to explore the neuroprotective actions of luteolin-treated microglia on dopaminergic neurons (Fig. 6A). A 0.4 µm pore-sized membrane was used to separate BV2 and PC12 cells. After treatment with LPS, luteolin, or LPS combined with luteolin, BV2 cells were then transferred to the co-culture system and co-cultured with PC12 for an additional 48 h. After this, PC12 apoptosis was measured by flow cytometry (Fig. 6B), and cell survival was measured using a CCK-8 assay. For the analysis of apoptosis, pretreatment of BV2 cells with luteolin significantly decreased the apoptotic response of PC12 cells (p = 0.002) compared to BV2 cells challenged with LPS-only (Fig. 6C). For the CCK-8 cell viability analysis, pretreatment with luteolin in BV2 prior to LPS administration remarkably increased cell viability of PC12 (p = 0.027) when compared to LPS-only cells (Fig. 6D). These in vitro results suggest that luteolin treatment of BV2 cells robustly ameliorates inflammation-induced neuronal injury.

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Luteolin pretreatment before LPS challenging in BV2 rescues

neuronal injury in the co-cultured system. (A) A sketch of the co-culture system

used. (B) Cellular apoptosis examined by flow cytometry. (C) Bar graph showing

the cellular apoptosis. (D) Cell viability was examined by Cell Counting kit-8

(CCK-8). N = 4 per group. ***p

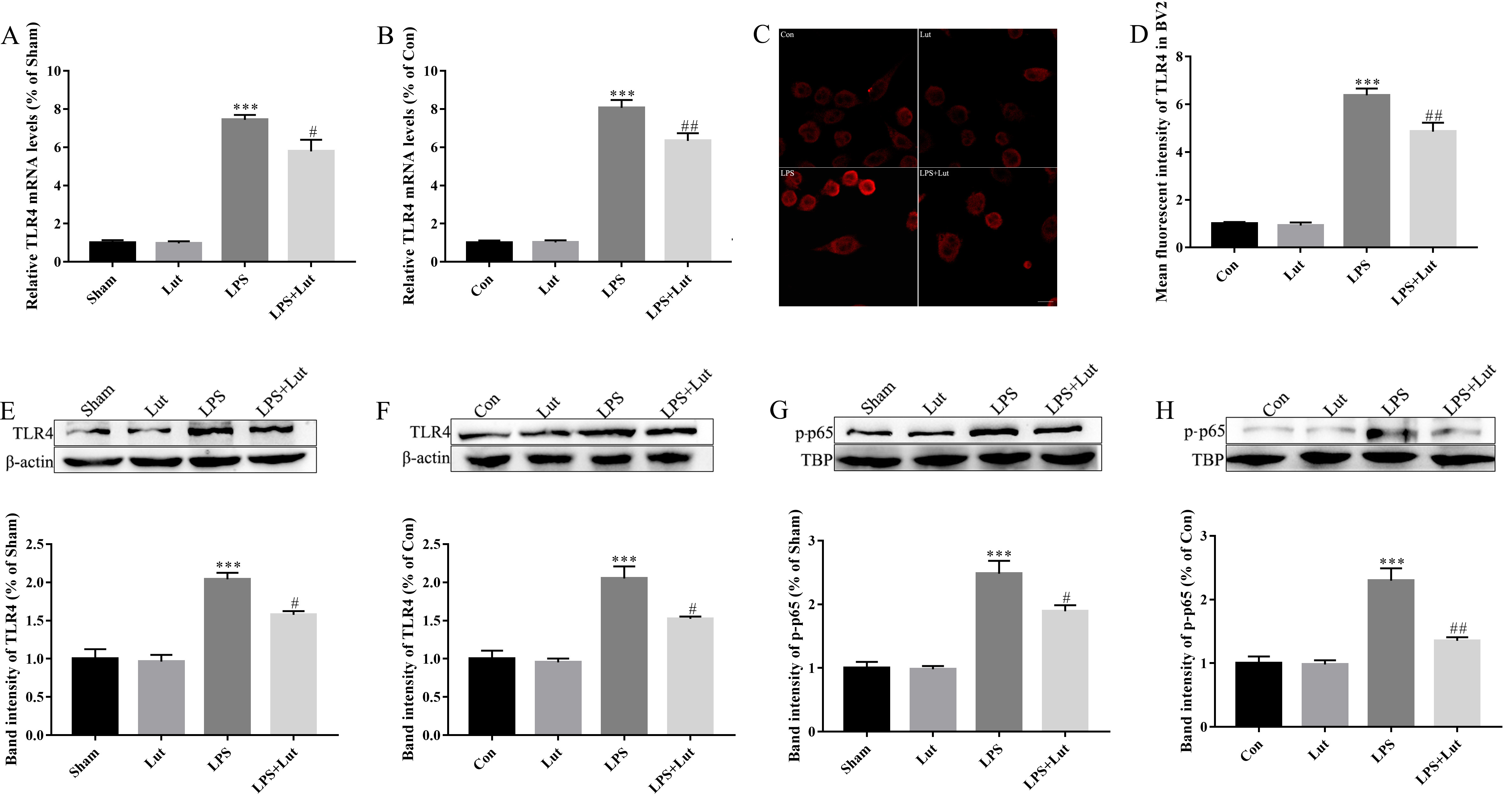

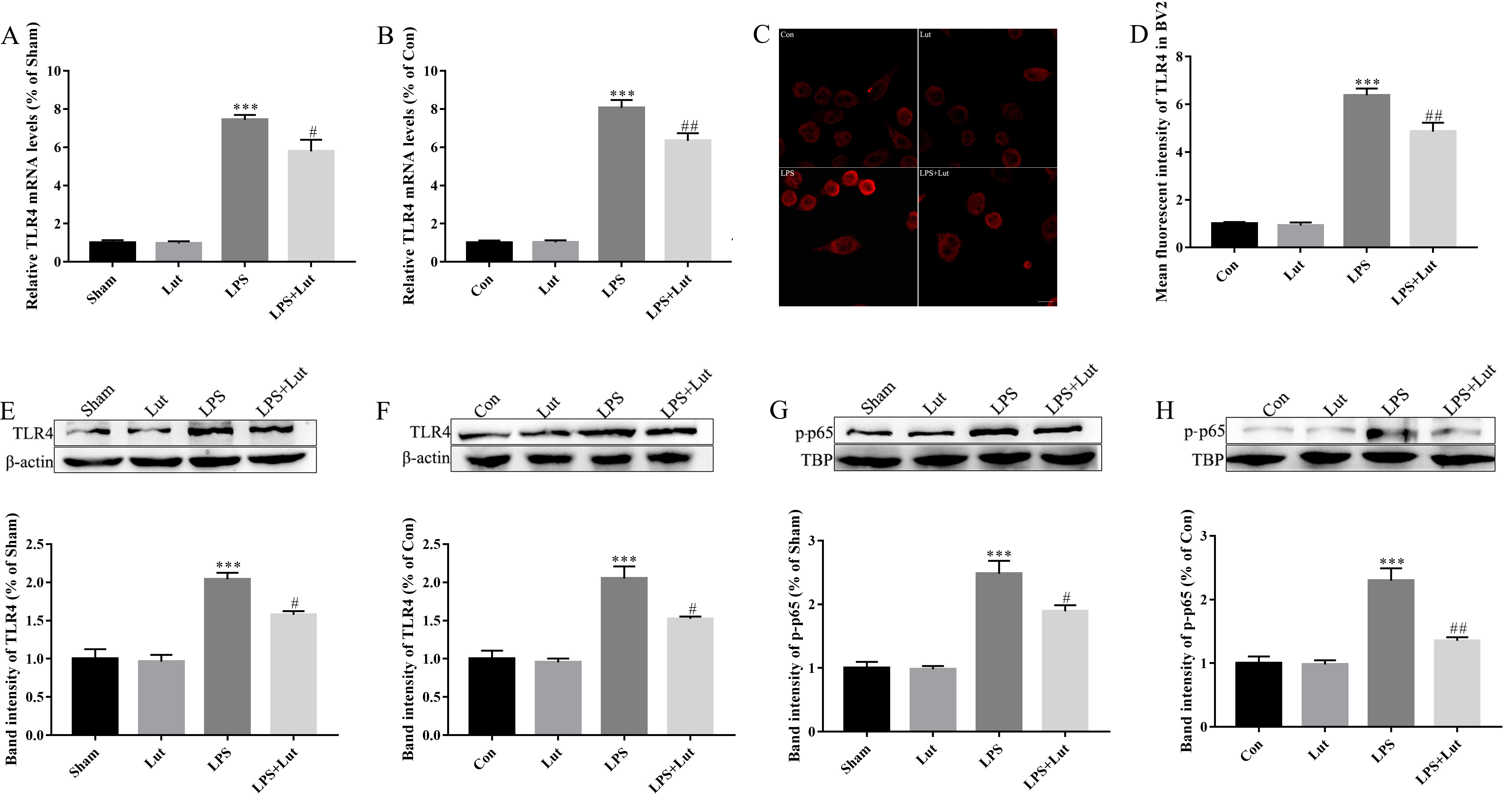

TLR4/NF-

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Luteolin treatment reduces LPS-induced TLR4/NF-

LPS treatment was also observed to significantly increase the abundance of

phosphorylated (activated) NF-

In this study, we explored the neuroprotective actions of luteolin during

inflammation-induced dopaminergic injury using both in vitro and

in vivo model systems. The results showed that luteolin treatment

induced a functional improvement in this response, and protected against

dopaminergic neuronal loss. Luteolin treatment also promoted dopaminergic

neuronal survival when PC12 neuronal cells were co-cultured with BV2 microglia

challenged with LPS. Moreover, luteolin treatment shifted microglial M1/M2

polarization towards an anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype and blunted

pro-inflammatory cytokine release in both in vitro and in vivo

model systems. Mechanistically, our findings suggest that luteolin treatment

deactivated TLR4 and downstream NF-

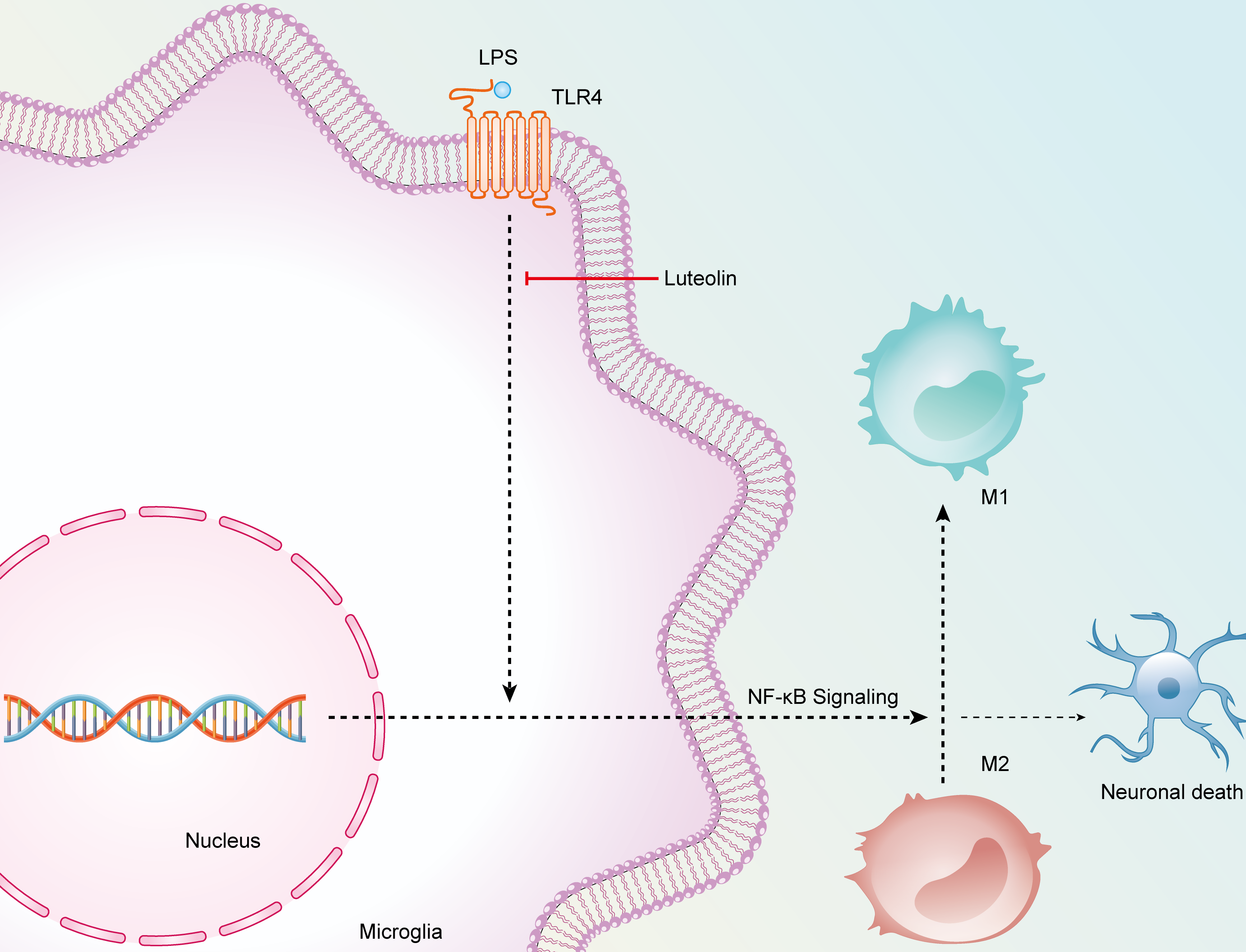

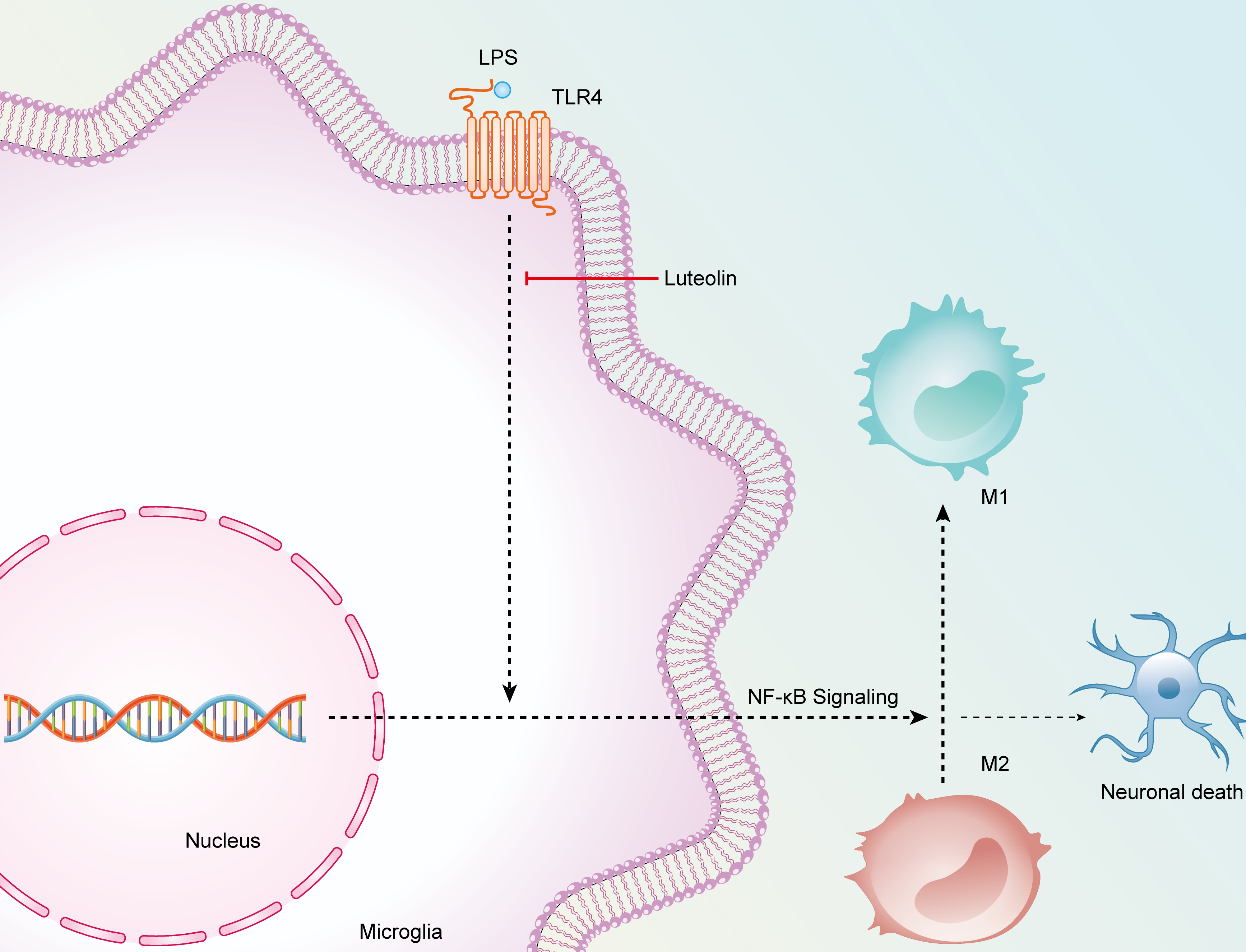

Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

The schematic diagram elucidating the anti-inflammatory/neuroprotective potential of luteolin.

Microglial polarization imbalance is a key factor in the development of neurodegenerative brain. Moreover, there is the possibility of mutual transformation between M1 and M2 microglial phenotypes corresponding to specific treatments. Therefore, we recognize the potential therapeutic value in agents that, in situations where phenotypical M1 microglia are over-activated, facilitate the transformation of M1-type microglia into M2 type and maintain a relative balance of M1/M2 cells. Luteolin has a variety of physiological actions in vivo, such as anti-inflammatory effects, antioxidant action, and estrogen-like effects [16, 17, 18]. In accordance with our findings, a prior study indicates that luteolin functions in a neuroprotective capacity during response to dopaminergic injury by limiting inflammatory response [19]. However, the mechanism(s) that govern such response remain unclear. We found that in LPS-treated PD mouse model and cultured BV2 cells, luteolin intervention restrained the M1-type microglia activation, mitigated the pro-inflammatory cytokines release, and enhanced the activation of anti-inflammatory M2-type microglia resulting in a restoration of the M1/M2 ratio. These effects reduced the neuronal damage that occurs through inflammatory response. In our animal model, we further demonstrated that luteolin significantly blunts both dopaminergic neuronal injury and motor function in inflammation-induced PD mice. Because of limitations stemming from the blood-brain barrier, classic anti-inflammatory drugs are of limited benefit in the treatment of neurological diseases [20]. Luteolin is a highly active natural polyphenol that crosses the blood-brain barrier, thus luteolin is potentially a more robust compound for the treatment and prevention of inflammatory responses mounted within the central nervous system [21].

Although the anti-inflammatory actions of luteolin have been vastly studied, its

downstream effector targets remain unclear. Consistent with our results, prior

studies have determined that LPS triggers the activation of TLR4 and downstream

NF-

We note some limitations in this study. For example, the concentration of luteolin in mouse brain tissue is unclear. More reliable methods for judging drug distribution are needed to better understand how luteolin reaches the brain. Tissue distribution of luteolin may be considered using in vivo imaging of animals or through high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) approaches. In addition, the anti-inflammatory effect of luteolin in TLR4-overexpressing microglial cells requires further examination.

In summary, our results indicate that luteolin protects against

inflammation-induced dopaminergic neuronal loss. Mechanistically, luteolin

deactivated TLR4/NF-

The data used and analyzed during the current study are available on reasonable request.

YX, HZ, JC, SX and YL performed the research. YX, HZ, and SX analyzed the data. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of The Affiliated Nanhua Hospital (protocol code: 2024-KY-059).

We thank Ejear Editing for the preparation of the manuscript.

This work was supported by Natural Science Foudation Of Hunan Province (grant number 2023JJ50159).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.