1 Department of Clinical Nutrition, Faculty of Applied Medical Sciences, King Abdulaziz University, 21589 Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

2 Obesity and Lifestyle Unit, King Abdulaziz University Hospital, 21589 Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

3 Department of Clinical Nutrition, College of Applied Medical Sciences, King Saud Bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences (KSAU-HS), 21423 Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

4 King Abdullah International Medical Research Center (KAIMRC), 21423 Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

5 Clinical Nutrition Department, King Abdulaziz University Hospital, 21589 Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

6 Department of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, King Abdulaziz University, 21589 Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

Abstract

Hypertension increases cardiovascular risk in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) patients. Magnesium is an important nutrient that promotes vascular function and insulin sensitivity, yet its potential role in managing blood pressure (BP) in patients with T2DM remains unclear. This study evaluates the impact of a magnesium-focused nutrition education intervention on dietary magnesium intake and BP control in patients with T2DM.

Thirty patients with T2DM (25 women; mean age, 55.7 ± 9.8 years; body mass index, 33.44 ± 7.17 kg/m2) participated in two clinical visits for data collection and BP measurement and received 12 weeks of magnesium-focused nutrition education to promote dietary magnesium intake.

The education intervention significantly increased dietary magnesium intake by 81.81 mg (p < 0.001). However, there were no significant changes in systolic or diastolic BP. Analysis showed no significant correlation between dietary magnesium intake and systolic or diastolic BP (p ≥ 0.56).

While the intervention successfully increased dietary magnesium intake, it did not affect BP. These findings suggest that increasing dietary magnesium intake through nutrition education may not significantly impact BP in individuals with T2DM. However, further research is needed to confirm these results and explore other factors that may influence BP management in this population.

Keywords

- hypertension

- dietary magnesium

- health education

- diet therapy

- type 2 diabetes

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a long-term metabolic condition that arises when pancreatic beta cells fail to produce enough insulin to counter insulin resistance, resulting in hyperglycemia [1]. It is a major health issue worldwide, with around 508 million individuals affected, and this number is expected to exceed 1.27 billion by 2050 [2]. Saudi Arabia has a particularly high prevalence of T2DM, estimated at 11.3% in 2021, and it is expected to double by 2050 [2]. Cardiovascular disease is one of the most concerning complications of T2DM, with hypertension being a major contributing factor. Recent data reveal that approximately half of individuals diagnosed with T2DM also have hypertension [3, 4]. Therefore, interventions aimed at successfully controlling blood pressure (BP) in people with T2DM are crucial, as the presence of hypertension significantly increases the risk of cardiovascular events, such as stroke, in this population [5, 6].

Diet plays a key role in managing T2DM and its associated complications. Standard dietary recommendations for adults with T2DM emphasize having a personalized dietary plan that is high in nutrient-rich foods, such as whole grains and fruits, and low in processed foods and added sugars [7, 8, 9]. Among the various nutrients, magnesium, an essential major mineral, has gained attention for its protective and therapeutic roles in T2DM and its related complications [10, 11, 12, 13]. The recommended daily intake of magnesium for adults is approximately 320 mg for females and 420 mg for males, which can be met through regular consumption of magnesium-rich foods such as whole grains, dark leafy greens, legumes, nuts, and seeds [14]. Despite these recommendations, many adults do not meet adequate magnesium intake. Moreover, magnesium deficiency is especially prevalent among people with T2DM due to increased urinary excretion and reduced intake [15, 16]. In Saudi Arabia, reports indicate that nearly one-third of people with T2DM have hypomagnesemia, which has been linked to poor glycemic control and may negatively impact BP [15, 16]. These findings underscore the need for practical interventions to promote dietary magnesium intake in high-risk populations.

Evidence from cross-sectional studies conducted on people with T2DM has shown that low magnesium intake or low serum magnesium was associated with poor glycemic [17, 18, 19] and BP control [19]. In addition, clinical studies have demonstrated that magnesium supplementation can greatly lower both systolic and diastolic BP, particularly in individuals with T2DM and hypomagnesemia [11, 20, 21]. Recent research has linked magnesium deficiency to the pathogenesis of hypertension through various mechanisms, including the alteration of L-type Ca2+ and endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) activity, prostacyclin release, and others [22]. While research has focused on supplementation, magnesium intake in the diet has also been shown to be inversely associated with hypertension development in general populations [23, 24, 25, 26], suggesting that promoting higher dietary magnesium intake could yield similar benefits in people with T2DM.

Nutrition education represents a practical, widely adoptable approach to promote dietary magnesium intake and support self-management in individuals with T2DM. Studies show that nutrition education interventions combining knowledge, practical skills, motivation, and follow-up effectively promote sustainable dietary changes and improve adherence to recommendations [27, 28]. In clinical practice, such interventions are delivered through medical nutrition therapy, in which registered dietitians provide individualized counseling to help patients meet therapeutic dietary goals [29]. A recent meta-analysis recommends delivering nutrition education for a minimum of three months, with personalized education being particularly effective for glycemic control in people with T2DM [24]. Dietary patterns that emphasize plant-based, minimally processed foods, such as the dietary approach to stop hypertension (DASH) and Mediterranean diets, are rich in magnesium and have been shown to improve BP and metabolic outcomes in both clinical and population-based studies [30]. A recent cross-sectional study, involving 2195 adults (40–59 years old), reported lower systolic BP readings in persons following the DASH dietary pattern. Furthermore, calcium and magnesium intake, whether from DASH or non-DASH foods, was independently associated with lower systolic BP after adjustment for supplement use, suggesting that these minerals contribute to the DASH–BP relationship [31]. These results support the rationale of increasing dietary magnesium intake through food-based strategies to achieve health benefits. However, limited research has specifically examined the effectiveness of magnesium-focused nutrition education interventions, as opposed to broader dietary education or supplementation studies, particularly in individuals with T2DM [32]. Thus, this study investigates the effect of magnesium-focused nutrition education on BP in adults with T2DM in Saudi Arabia. We hypothesize that raising the consumption of magnesium-rich foods will improve BP, an essential component of T2DM management that frequently poses challenges in the clinical setting.

This study followed a quasi-experimental (within-subject) design to assess the

impact of a tailored magnesium-focused education intervention on BP. Change in BP

was the primary outcome. Participants were eligible if they were men and women

aged 18 years and older who had a body mass index (BMI) of 18.5 kg/m2 or

higher and were diagnosed with T2DM and hypertension and their diagnosis could be

verified based on medical records and endocrinologist evaluation following

international diagnostic criteria (e.g., fasting plasma glucose

Participants were recruited by convenience sampling through endocrinologists in outpatient clinics. Qualified individuals were invited for an in-person interview to evaluate their interest and willingness to participate. The prospective participants were referred to the dietitian at the nutrition clinic to evaluate their eligibility based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. A registered dietitian, trained in standardized assessment techniques, confirmed eligibility and provided orientation about the study.

The study included two clinical visits: baseline (week 0) and follow-up (week 12). Upon acquiring informed consent, baseline demographic information (e.g., educational attainment, marital status), medical history, the beginning of T2DM, anthropometric measurements, and BP were gathered. Measurements were taken by a trained dietitian using standardized procedures. Body weight was recorded to the nearest 0.1 kg with a calibrated digital scale, while participants wore light clothing and no shoes. Height was measured with a stadiometer to the nearest 0.1 cm, and BMI was calculated as weight (in kg)/height (in m2).

BP measurements (in mm Hg) were obtained by an experienced nurse in accordance with American Heart Association guidelines using an automated and validated oscillometric monitor (Omron® digital device, BP5000, Lot # 20090600368LF, Omron Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) from the nondominant arm in a relaxed position. Two measurements were taken, and the average of the two readings was used.

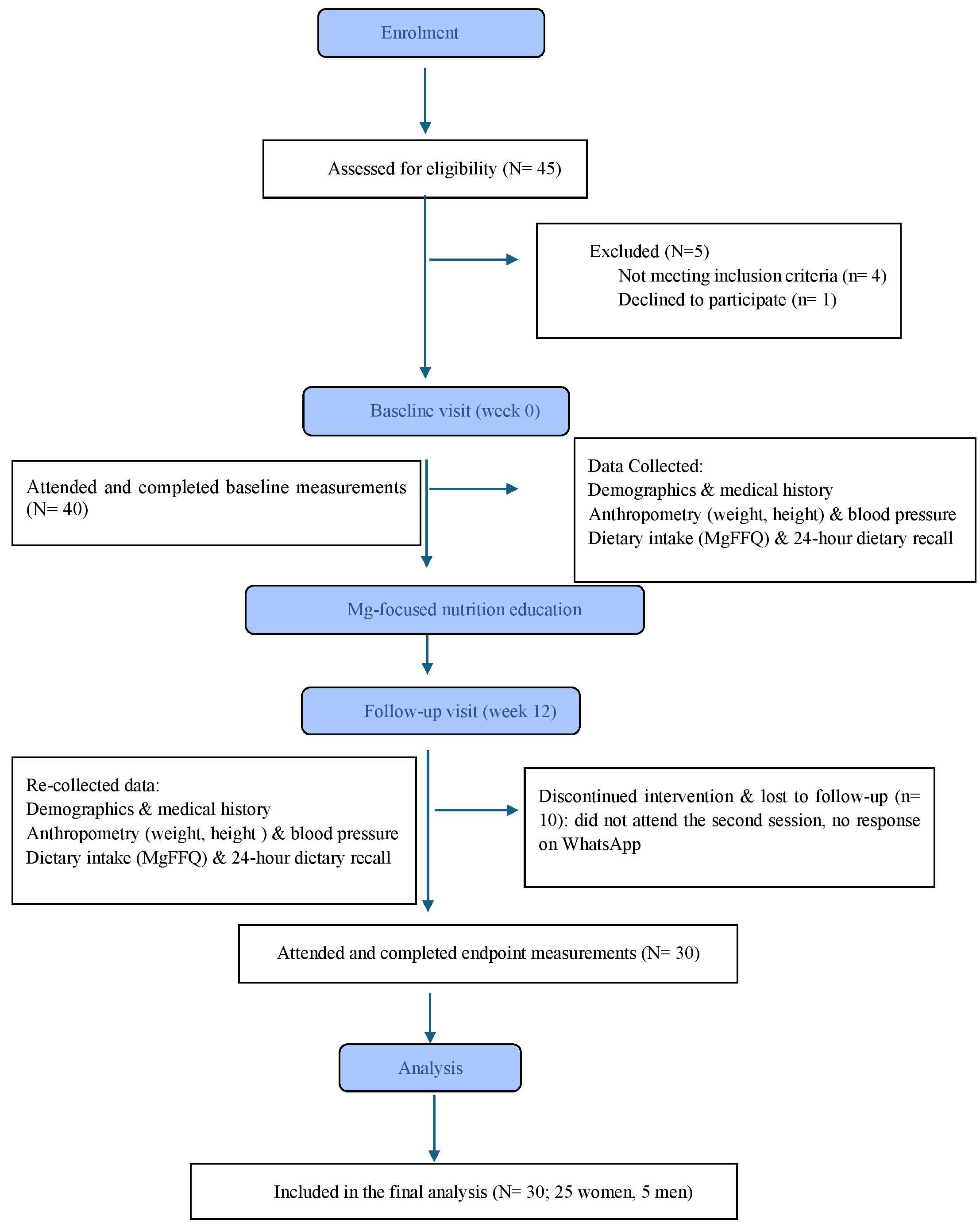

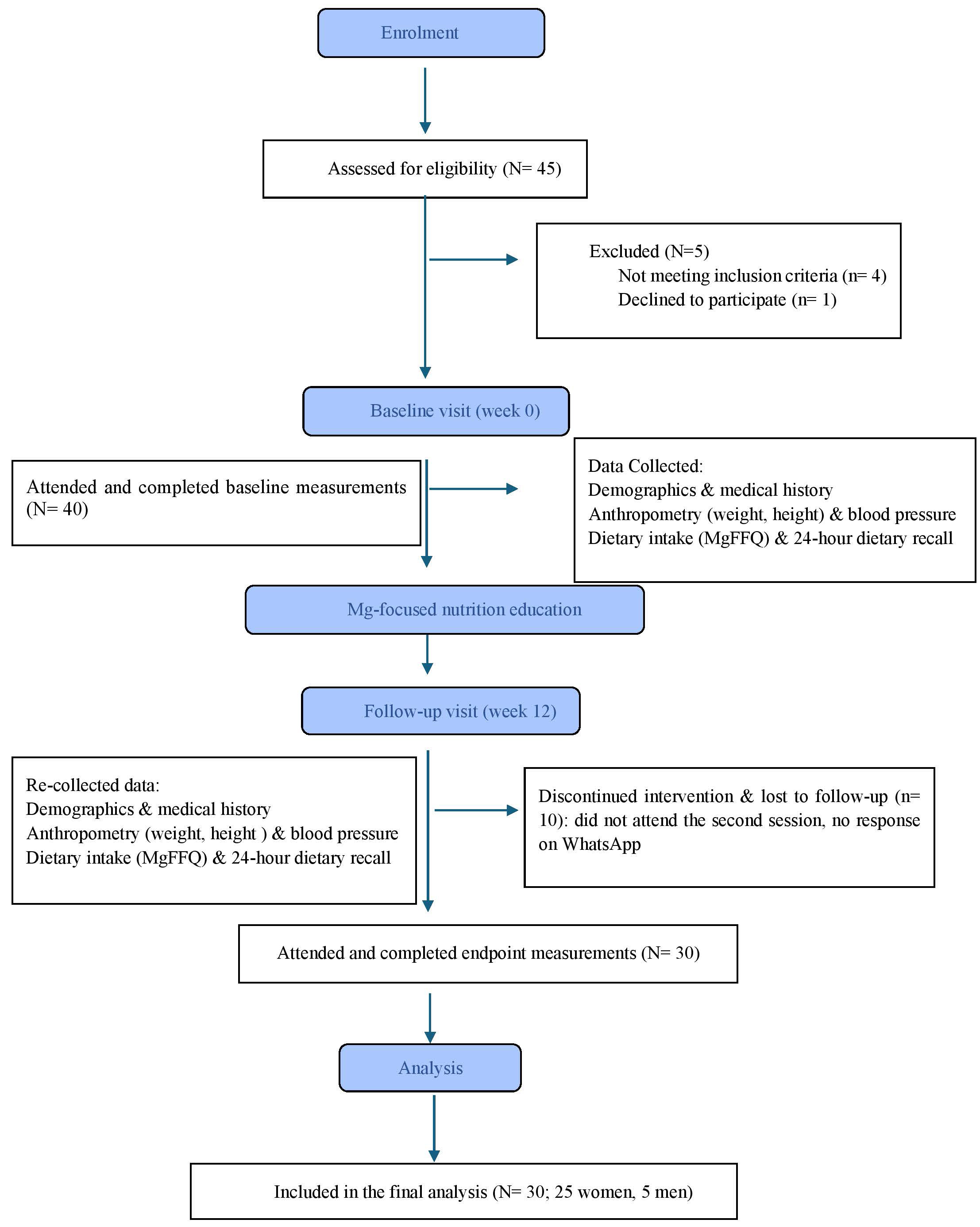

Participants received in-person nutrition counseling (magnesium-focused nutrition education) at baseline (week 0) and in the follow-up visit on week 12. Each clinical session lasted approximately 30 to 45 minutes. During the counseling session, a registered dietitian, a co-investigator in the study, explained the research objectives and intervention protocol in detail. This ensured consistency of delivery and alignment with the study goals. To support adherence, participants also received reminders every three weeks through WhatsApp, which included educational tips, a list of magnesium-rich foods, and the opportunity to ask questions. Participant recruitment and progression through the study are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

CONSORT flow diagram of participant recruitment and study flow. MgFFQ, Magnesium Food Frequency Questionnaire.

All procedures involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the Research and Ethics Committee at King Abdulaziz University Hospital (Reference No.: 361-21). Written informed consent forms were signed by all participants before participation in the study.

Magnesium (Mg) consumption was evaluated solely from dietary sources without supplementation. At both study visits, baseline and follow-up, intake was evaluated using the validated 33-item Mg Food Frequency Questionnaire (MgFFQ), which estimates long-term dietary magnesium from consumption by the portion sizes and consumption frequency of magnesium-rich foods and beverages. The questionnaire includes foods ranging from the highest to the lowest magnesium content. Examples of food items include dark leafy greens (Kale, spinach), nuts and seeds (cashews, pecans), fish (salmon, mackerel), grains (brown rice, white bread), and dairy products (yogurt, milk). A detailed description of the MgFFQ has been previously published [34]. Although this food frequency questionnaire was originally validated against 14-day food diaries in non-Saudi populations [34], it has not yet been formally validated in Saudi Arabia. To strengthen dietary assessment and account for cultural variability, we complemented the MgFFQ with repeated 24-hour dietary recalls.

During the initial counseling session, individualized caloric needs and magnesium requirements were determined using the calorie calculator provided by the Saudi Ministry of Health. Using the recommended dietary allowance (RDA) guidelines established by the Institute of Medicine’s Standing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary Reference Intakes (1997), the recommended daily intake of magnesium for adults was determined. The RDA is set to meet the needs of healthy individuals [35]. Based on energy requirements and sex, a personalized meal plan was created for each participant and explained. A one-day sample menu was provided to illustrate suitable food choices and portions that met both caloric and magnesium needs. The meal plans provided 420 mg of magnesium daily for males and 320 mg for females. During the 12-week intervention, participants received guidance on incorporating magnesium-rich foods into their daily diet, including recommended servings from each food group. Emphasis was placed on sources such as leafy greens, whole grains, nuts, seeds, and legumes. A practical food list was also provided to support flexibility and adherence.

Three 24-hour dietary recalls were obtained from the participants, at study commencement and toward the conclusion of the intervention, focusing on weekday intake. The recalls were evaluated utilizing the Automated Self-Administered Dietary Assessment (ASA24) tool, a prevalent instrument for extensive dietary research. Throughout the intervention period, participants received WhatsApp messages to promote compliance and encourage them to ask questions if they needed additional information. During the follow-up session on week 12, changes were assessed. Key educational content provided to the participants is presented in Table 1. Full details of the methodology have been previously published [32].

| Component | Content details | Examples/materials provided |

| Educational material 1 | - Caloric requirements based on sex | - Sample meal plan showing three meals + 2 snacks |

| Baseline visit | - RDA for magnesium by sex | - Serving size charts by food group |

| - Recommended servings from each food group | - Visual guide for balanced meals with annotated portion sizes | |

| - Examples of servings from food groups throughout the day | ||

| Educational material 2 | - Foods high in magnesium across food groups | - Food list by group with magnesium content |

| Baseline visit | - Drugs that may interfere with magnesium absorption or status | - Caution list of medications and interactions |

| Weekly educational titles | - “Ways to Increase Magnesium Intake” | - Food suggestions with serving sizes and magnesium amount per item |

| - “Magnesium-Rich Foods with Serving Sizes and Magnesium Content” (3 parts) | - Visual handouts |

RDA, recommended dietary allowance.

The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess normality for continuous data

(differences in dietary magnesium intake and systolic and diastolic BP). As the

preintervention data indicated a skewed distribution, nonparametric tests were

applied. Differences in systolic and diastolic BP before and after the nutrition

intervention were examined using the Wilcoxon signed rank test. Pearson

correlation was used to explore associations between dietary magnesium and BP

after the intervention. For all statistical tests, significance level was set at

a priori p value of

A priori power analysis was conducted using G*Power software version 3.1.9.2, (https://www.psychologie.hhu.de/arbeitsgruppen/allgemeine-psychologie-und-arbeitspsychologie/gpower), specifying a power of 0.80, a medium effect size of Cohen’s d = 0.5, and an alpha level of 0.05. The analysis indicated that a minimum sample size of 85 participants would be required to achieve adequate statistical power. Nevertheless, difficulties faced during the recruitment process affected our ability to achieve the desired sample size.

Thirty participants were included. All were over forty years old (mean age 55.7

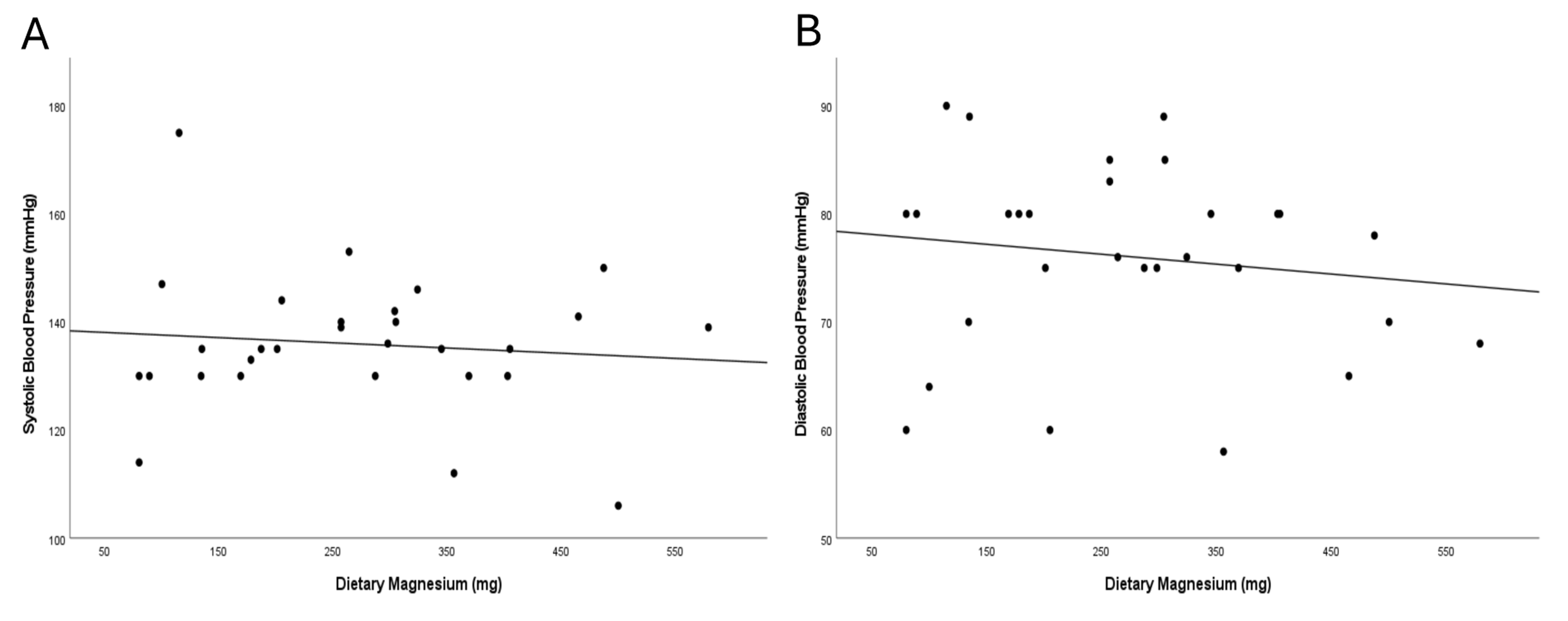

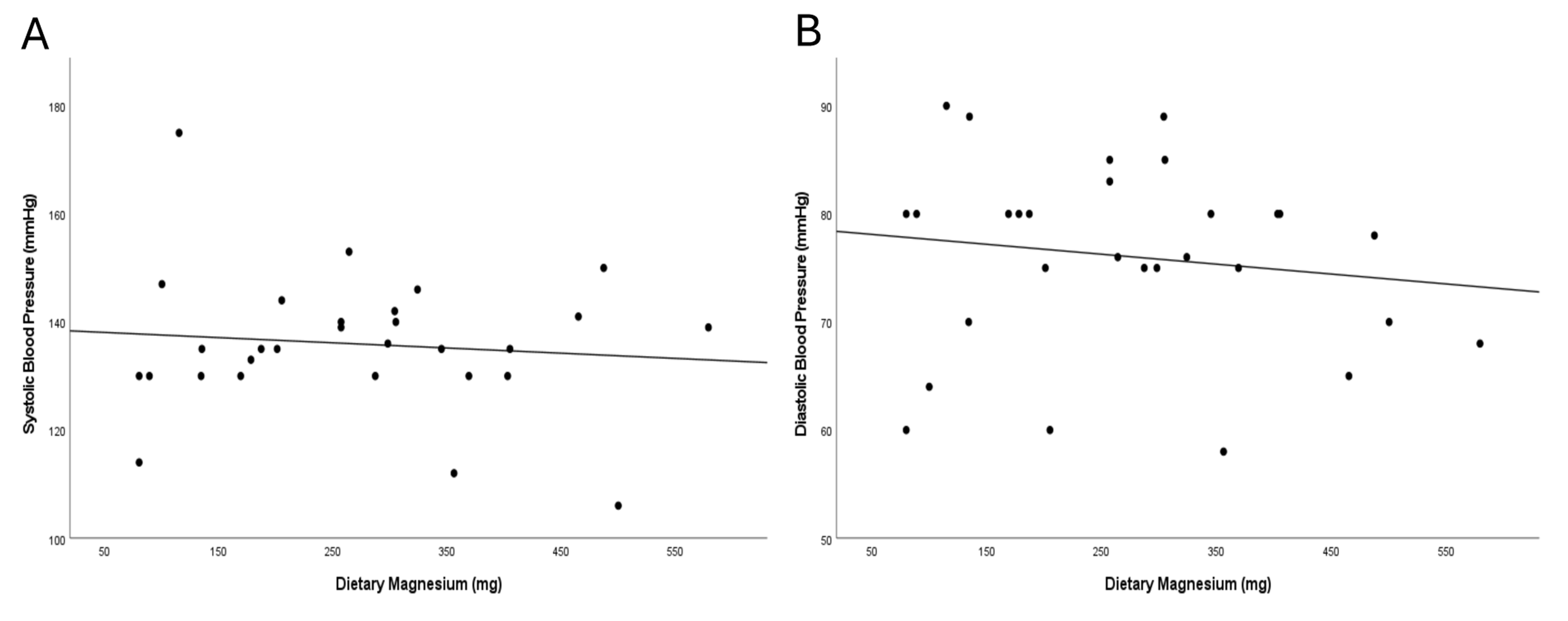

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Correlation between dietary magnesium intake and blood pressure after the nutrition intervention, measured by Pearson correlation. (A) Dietary magnesium (mg/day) vs. systolic BP (mmHg); least-squares fit shows a slight inverse trend magnesium intake and SBP. (B) Dietary magnesium (mg/day) vs. diastolic BP (mmHg); least-squares fit shows a slight inverse trend magnesium intake and SBP.

| Variable | N = 30 | |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Female | 25 (83.3) | |

| Male | 5 (16.6) | |

| Age (years), mean |

55.7 | |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean |

33.44 | |

| Education, n (%) | ||

| Elementary & secondary | 15 (50) | |

| Bachelor’s | 13 (43.3) | |

| Postgraduate | 2 (6.6) | |

| Marital status, n (%) | ||

| Single | 1 (3.3) | |

| Married | 29 (96.6) | |

| Antihypertensive medication use, n (%) | 15 (50) | |

| Duration of diabetes, n (%) | ||

| Less than 5 years | 0 | |

| 5–10 years | 17 (57) | |

| 13 (43) | ||

| Smoking status | ||

| Current smoker | 4 (13) | |

| Former smoker | 6 (20) | |

| Never smoked | 20 (67) | |

Note. BMI, body mass index; SD, standard deviation. Adapted with permission from Albajri E et al. [32].

| Variable | Preintervention | Postintervention | p value |

| Mean |

Mean | ||

| Dietary magnesium intake measured by the MgFFQ (mg) | 185.64 |

267.45 |

|

| (women: 203.15 |

(women: 260.50 |

||

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 137 |

136 |

0.278 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 74 |

75.5 |

0.637 |

SD, standard deviation; MgFFQ, Magnesium Food Frequency Questionnaire.

* Statistically significant differences.

| Systolic blood pressure | Diastolic blood pressure | |||

| r | p value | r | p value | |

| Dietary magnesium intake | –0.10 | 0.60 | –0.14 | 0.45 |

Statistical significance set at p

In this study, we evaluated the impact of magnesium-focused nutrition education on BP among patients with T2DM. We observed no significant changes in BP following the intervention. A similar outcome has been reported by a study using a 12-week education program that encouraged a healthy lifestyle and reduced dietary salt intake [36]. In addition, a scoping review found that nutrition education interventions often improve dietary behaviors without translating into significant BP or other physiological improvements [37].

Although the magnesium-focused educational sessions significantly increased

dietary magnesium intake, demonstrating the strategy’s effectiveness and value as

an interventional approach [38], they did not result in a measurable impact on BP

in our T2DM patients. In our study, mean daily magnesium consumption rose from

185.64

High doses of magnesium may be easier to achieve through supplementation than through the diet, as obtaining equivalent amounts from food would require consuming large volumes of magnesium-rich items—potentially disrupting an individual’s total caloric balance [45]. Accordingly, any dietary intervention aiming to boost magnesium intake should be very well structured, since increasing mineral intake via whole foods inevitably alters overall energy consumption and macronutrient proportions [46]. In our study, although magnesium intake increased following the intervention, it remained below the recommended daily intake and the effective supplement doses (300–400 mg/day) used in trials [20]. This may explain the absence of a significant changes in blood pressure. We also focused our intervention on dietary magnesium; however, magnesium-rich foods also provide potassium and fiber, both of which are associated with blood pressure regulation [47, 48]. The consumption of fiber and potassium has been associated with modest reductions in blood pressure through improvements in vascular function [47, 48]. On the other hand, excessive phytate intake may impair mineral absorption, including magnesium, potentially attenuating these effects [49]. As a result of this overlap, it is inherently difficult for nutrition education studies to isolate magnesium’s independent effects. However, the modest increases in magnesium intake in our cohort, along with any possible concurrent dietary changes, did not produce measurable changes in blood pressure. Generally, discrepancies may reflect differences in study design, population characteristics, or dosing regimens. Furthermore, nuts and seeds, as well as whole grains, were the main sources of increased magnesium intake. This aligns with earlier studies that identify nuts, seeds, and whole grains as key dietary sources of magnesium and important for better cardiometabolic health [50, 51]. Therefore, our findings indicate that patients included a variety of magnesium-rich foods in their diets instead of relying only on single foods or supplements.

This study has several limitations to consider. Firstly, the sample size was fairly small, with only 30 participants, which may influence the results and limit generalizability of findings. The sample also showed gender imbalance, with an 83.3% female dominance. This may also affect generalizability, as dietary adherence, magnesium metabolism, and vascular reactivity differ by sex [51]. Additionally, magnesium intake was assessed through a self-reported questionnaire, and while the MgFFQ is a validated tool [35], it has not been formally adapted to Saudi populations. The absence of biochemical assessment, such as serum or red blood cell magnesium levels, limits the ability to confirm whether physiological magnesium status improved. Furthermore, key socioeconomic and psychosocial variables such as income, stress, or mental health were not measured, despite their potential influence on dietary behaviors and BP. Although individuals taking diuretics were excluded, half of the included participants were on other antihypertensive medications, which may have masked potential effects of dietary magnesium [48, 50]. Lastly, the study did not include a control group, limiting the ability to infer causality, and the 12-week duration may have been insufficient to capture the full impact of dietary changes on vascular health [49].

Although this study did not demonstrate a significant effect of magnesium-focused education on improving BP, it provides useful preliminary insights. The findings suggest that implementing individualized, culturally adapted nutrition counseling is feasible in a clinical setting and may help to improve dietary magnesium intake. Future studies should include larger and more diverse populations, aim for higher magnesium doses (e.g., through fortified foods) that meet recommendations, utilize objective biochemical assessments of magnesium status, and extend the intervention duration beyond three months. Stratifying the analysis by sex and adjusting for potential confounders such as potassium and fiber would also help clarify the specific impact of dietary magnesium on BP. Additional studies should isolate magnesium’s effects. Finally, combining nutrition education with broader lifestyle strategies, such as physical activity and stress reduction, may offer greater potential to improve clinical outcomes.

Although the magnesium-focused nutrition education program increased magnesium intake, it did not result in significant changes in BP among individuals with T2DM. These findings highlight the complexity of dietary interventions and suggest that magnesium intake alone, when sourced from food and over a short period, may be insufficient to modify BP in this population. Further investigation with more rigorous study designs and longer durations is warranted to clarify the role of magnesium in BP regulation for people living with T2DM.

BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; DASH, dietary approach to stop hypertension; MgFFQ, Mg Food Frequency Questionnaire; SD, standard deviation; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

The data may be released for the reviewers and editor but not for the public due to the policy of the authors and university.

Conceptualization: MN, EA and AA; Data curation: MN, EA, RB, SN and HM; Formal analysis: EA, MN, NH, and SA; Investigation: MN; Methodology: MN, EA, NH, and SN; Project administration: MN and EA; Resources: MN, AA, & SN; Software: EA; Writing—original draft: MN, EA, AA, NH, SA, & RB; Writing—review & editing: MN, EA, AA, NH, SA, SN & RB and HM. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of King Abdulaziz University Hospital (Reference No.: 361-21), and all of the participants provided signed informed consent.

Not applicable.

The project was funded by KAU Endowment (WAQF) at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, grant no.(WAQF:156-290-2024). The authors, therefore, acknowledge with thanks WAQF and the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) for technical and financial support.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.