1 Endocrine Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, 5165665931 Tabriz, Iran

2 Department of Occupational Therapy, Faculty of Rehabilitation Science, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, 5165665931 Tabriz, Iran

3 Nutrition Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, 5165665931 Tabriz, Iran

4 Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Research Center, Aging Research Institute, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, 5165665931 Tabriz, Iran

Abstract

Diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN), a prevalent microvascular complication of diabetes mellitus, poses a substantial clinical burden and has a detrimental impact on quality of life. This triple-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial investigated the effects of an 8-week supplementation with selenium-enriched yeast on DPN symptoms, neuropathy severity, pro-oxidant–antioxidant balance (PAB), and sexual satisfaction in individuals aged 40–70 years with DPN.

Fifty participants were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive either a daily 200 μg dose of Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeast-derived selenium (in a 500 mg capsule) or a placebo. Outcomes were assessed using validated tools: The Michigan Neuropathy Screening Instrument (MNSI) for symptoms, the Toronto Clinical Scoring System (TCSS) for severity, the Larson Sexual Satisfaction Questionnaire (LSSQ), and serum PAB levels via a specialized assay. Analyses followed a modified intention-to-treat approach, with ANCOVA and logistic regression used to adjust for confounders.

Post-intervention, both groups exhibited significant reductions in neuropathy symptoms (selenium: p < 0.001; placebo: p = 0.001), though intergroup differences were non-significant [adjusted mean difference (aMD): –0.92; 95% CI: –1.9 to 0.10]. Neuropathy severity decreased significantly in the selenium group (p = 0.002) but not in the placebo group. While PAB levels declined markedly with selenium (p = 0.001), the between-group difference was non-significant (aMD: –32.1; 95% CI: –66.02 to 1.87). Sexual satisfaction scores improved significantly in the selenium group versus the placebo group (aMD: 8.51; 95% CI: 0.74 to 16.28).

These findings suggest that selenium-enriched yeast supplementation may enhance biochemical markers (PAB) and quality-of-life parameters (sexual satisfaction) in DPN. However, its limited efficacy in improving neuropathy-specific outcomes underscores the need for larger trials to clarify its therapeutic potential.

This trial was registered at the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT20131009014957N10, https://trialsearch.who.int/Trial2.aspx?TrialID=IRCT20131009014957N10).

Keywords

- diabetic neuropathy

- selenium

- supplementation

- symptom assessment

- severity of illness

- oxidative stress

• Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy (DPN) is a common microvascular complication of

diabetes mellitus. • Some studies revealed that blood selenium levels and DPN are closely related. • We evaluated the effect of organic selenium on symptoms and severity of DPN,

oxidative stress, and sexual satisfaction. • We observed the significant effect of selenium on improving the severity of DPN,

oxidative stress, and sexual satisfaction. • Further investigations are suggested to confirm the therapeutic effects of

selenium on neuropathy outcomes.

Diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN), a prevalent microvascular complication of diabetes mellitus (DM) [1], is characterized by significant clinical implications and substantial deterioration in patient quality of life [2]. This condition elevates risks of morbidity and disability, primarily through complications such as neuropathic ulceration and subsequent limb amputation [1]. Pathophysiologically, DPN manifests as symmetric sensorimotor polyneuropathy mediated by metabolic and microvascular alterations arising from chronic hyperglycemia and associated metabolic dysregulation [3].

The condition typically originates in the toes and progresses proximally [2], presenting clinically with both positive and negative sensory symptoms. Positive manifestations include paresthesia, burning pain, and neuropathic discomfort, while negative features encompass hypoesthesia (reduced tactile sensation), hypoalgesia (diminished pain perception), and palhypesthesia (decreased vibratory sensitivity) [4]. These sensory deficits contribute to impaired balance, gait instability, and elevated fall risk, potentially precipitating fractures and hospitalization [5]. Motor complications such as muscle weakness and spasms occur less frequently [6]. DPN is strongly associated with increased risks of lower extremity ulceration, limb amputation, and significant healthcare expenditures [7, 8, 9]. Early-stage pathophysiology involves segmental demyelination impairing nerve conduction velocity [10], progressing to axonal degeneration and myelin sheath damage. Diagnosis relies on nerve conduction studies (NCS) to differentiate DPN from other neuropathies [2].

Epidemiological studies reveal substantial global heterogeneity in DPN prevalence, attributed to variability in diagnostic criteria, diabetes subtypes, patient selection methodologies, and cohort sizes [11]. Reported prevalence rates demonstrate wide geographical disparities: 8.8% in China [12], 48.1% in Sri Lanka [13], 29.2% in India [14], 56.2% in Yemen [15], 39.5% in Jordan [16], 71.7% in Nigeria [17], 16.6% in Ghana [18], 26.5% in Malaysia [19], and 48.2% in Ethiopia [20]. Peripheral nerve degeneration in diabetes is typically irreversible [21, 22], underscoring the critical need for early intervention. Established risk factors include advanced age, male sex, prolonged diabetes duration, concurrent microvascular complications, hypertension, rural residency, elevated body mass index (BMI), poor glycemic control (indicated by elevated Hemoglobin A1C (HbA1c) levels), alcohol consumption, chronic hyperglycemia, tobacco use, sedentary lifestyle, and marital status [1].

Current pharmacological management of neuropathic pain and paresthesia utilizes anticonvulsants, tricyclic antidepressants, or serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors [23]. However, therapeutic strategies remain limited by the ineffectiveness of existing treatments for sensory loss [2], highlighting a critical gap in clinical management. The pathogenesis of DPN extends beyond hyperglycemia-mediated neuronal damage, involving complex interactions between molecular mechanisms [6]. Key dysregulated pathways include enhanced polyol pathway flux, advanced glycation end-product (AGE) accumulation, oxidative stress, altered growth factor signaling, impaired insulin/C-peptide axis function, and protein kinase C (PKC) overactivation [24, 25]. These processes simultaneously disrupt neuronal homeostasis and microvascular integrity within the vasa nervorum. Emerging pathophysiological models emphasize the convergence of multiple signaling networks and transcriptional regulators in DPN progression. Notably, extensive research has established oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and programmed cell death as pivotal mechanisms in diabetic nerve injury through interconnected biochemical cascades [26]. This multifactorial pathogenesis complicates the development of targeted neuroprotective therapies.

Selenium (Se) serves as an essential cofactor for antioxidant enzymes such as glutathione peroxidase (GPx), which neutralize reactive oxygen species (ROS) and prevent oxidative damage [27]. This micronutrient also contributes to the structural integrity of selenoprotein enzymes including deiodinase iodothyronine and thioredoxin reductase, which regulate thyroid hormone synthesis [28]. Clinical investigations have demonstrated an inverse relationship between blood selenium levels and DPN severity in type 2 diabetes patients [29]. Preclinical evidence from a 2011 rodent study (n = 40) revealed that sodium selenite supplementation mitigated diabetes-induced alterations in nerve conduction velocity distribution, restoring active nerve fiber parameters to age-matched control levels [30]. Similarly, selenate administration exhibited protective effects on electrophysiological parameters in diabetic models [30].

Selenoproteins, the biologically active forms of selenium, play critical antioxidant roles in numerous physiological processes [31]. Selenomethionine, the most bioavailable selenium species for human metabolism, accumulates efficiently in Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeast cultured in selenium-enriched media. Unlike inorganic forms, organic selenium derived from yeast undergoes site-specific amino acid absorption without mineral interactions, achieving complete bioavailability and systemic retention [32, 33, 34]. Selenium yeast supplementation is recognized as a safe, effective method for dietary fortification due to its superior absorption profile [35, 36]. Currently, Saccharomyces cerevisiae represents the most efficient organism for selenomethionine accumulation and selenium biotransformation [37].

Given the escalating global prevalence of type 2 diabetes and its debilitating complications, novel therapeutic strategies for managing DPN require urgent investigation. Our extensive search of the database identified no prior clinical trials examining organic selenium’s effects on DPN severity or symptomatology. This randomized controlled trial aimed to evaluate the efficacy of Saccharomyces cerevisiae-derived selenium over eight weeks on primary outcomes including neuropathic symptom severity and prooxidant-antioxidant balance (PAB) status, and a secondary outcome consisting of sexual satisfaction. This investigation seeks to address a critical gap in DPN management while elucidating selenium’s potential therapeutic mechanisms through oxidative stress modulation.

This triple-blind, parallel-group randomized controlled trial (RCT) enrolled participants aged 40–70 years with diagnosed DPN from outpatient clinics at Imam Reza and Sina Hospital in Tabriz, Iran. Ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (IR.TBZMED.REC.1401.374), and the trial was registered at the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT20131009014957N10; March 8, 2020). Researchers ensured protocol adherence through institutional authorization and strict compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki (1964) and its subsequent amendments. Prior to the intervention, participants received full disclosure of the study objectives, methodologies, potential risks/benefits, and withdrawal rights through direct researcher communication, followed by the acquisition of written informed consent.

Inclusion criteria encompassed: adults aged 40–70 years; a diagnosis of type 2

diabetes mellitus by an endocrinologist, including individuals with controlled

(HbA1c

Diabetes mellitus diagnosis followed WHO criteria: random plasma glucose

Initial eligibility screening incorporated completion of the Michigan Neuropathy Symptom Questionnaire. Qualified volunteers who provided written informed consent underwent randomization via block-based allocation (1:1 ratio) using Random Allocation Software (RAS 2.0, M. Saghaei, Isfahan, Iran), which assigned participants to either an organic selenium group or a placebo arm. Participants received sequentially numbered opaque containers (1–50) containing either 60 capsules of 500 mg selenium-enriched yeast (200 µg selenium) or visually indistinguishable placebo capsules, both prepared under third-party supervision at the Nutrition Research Center. A triple-blind randomization scheme, generated by an independent researcher, governed group allocation, with consecutive container distribution preserving allocation concealment. Researchers and participants remained blinded throughout the data collection and analysis phases, ensuring complete randomization integrity. All participants received standard clinical care alongside the intervention. The 500 mg capsules were identical across groups in physical characteristics (shape, color, weight, odor), maintaining triple-blind conditions between participants, researchers, and statistical analysts. Participants were instructed to ingest one capsule daily for two months.

The selenium-enriched yeast (Se-yeast) capsules contained 500 mg of Saccharomyces cerevisiae biomass incorporating 200 µg of organic selenium. Placebo capsules consisted exclusively of 500 mg of non-enriched Saccharomyces cerevisiae cultivated under identical growth conditions (media composition, incubation temperature, pH parameters, harvest phase) without selenium supplementation. Both formulations were synthesized in the laboratory of the Tabriz Nutrition Research Center, affiliated with Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, following established protocols from Rahimi et al. [38]. In brief, Se-yeast was produced through the aerobic fermentation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae in a selenium-supplemented medium. The base medium consisted of sugarcane or beet molasses, supplemented with vitamins, nutrients, and growth factors to maximize biomass production. Selenium was introduced in the form of sodium selenite. Several parameters influenced both yeast growth and selenium uptake efficiency, including temperature, pH, selenium concentration, timing of selenium addition, aeration rate, inoculum volume, inoculation timing, and medium composition. During fermentation, selenium was incorporated into the yeast in organic form. Following fermentation, the yeast cells were separated via centrifugation, thoroughly washed, and dried to remove residual inorganic selenium bound to the cell walls. The final product was formulated as a 500 mg capsule containing 200 µg of organic selenium. Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) analysis verified a selenium concentration of 12,600 ppm (12,600 µg/kg) within the active compound.

Participants received standardized training in capsule administration and

maintained daily medication adherence logs. Baseline evaluations included

completion of demographic surveys and neuropathy severity and sexual satisfaction

questionnaires. Anthropometric measurements employed calibrated instrumentation:

body weight was recorded to a precision of

The research team implemented weekly telephone follow-ups with participants to monitor medication adherence and protocol compliance. A dedicated contact number was provided to facilitate bidirectional communication, enabling subjects to address any study-related inquiries or concerns. Given that selenium functions as a nutritional supplement and considering the administered safe dosage—determined through preliminary safety assessments—no adverse effects were anticipated across medical, physical, mental, or psychological domains. Nevertheless, participants were explicitly informed that any suspected supplement-related complications would trigger immediate discontinuation of the intervention, accompanied by the provision of complementary medical management and follow-ups without any charge.

Following the 60-day intervention period, participants underwent repeat questionnaire administration and physiological assessments. The questionnaires on symptoms and severity of neuropathy and the sexual satisfaction questionnaire were completed again, and assessments were performed. The satisfaction with medication form was completed by asking patients on the pertinent sheet, and the drug side effects checklist was collected. A daily medication checklist and the used drug container were collected to count the remaining medication capsules. Fasting blood samples were collected the morning after intervention completion at a designated laboratory prior to initiating biochemical testing. The PAB assay was conducted using methodology adapted from Zahedi Avval et al. [39], involving sequential preparation of chromogenic substrates: a standard solution gradient combining 250 µM H2O2 (0–100%) with 3 mM uric acid in 10 mM NaOH; tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (60 mg/10 mL) subsequently mixed with acetate buffer (0.05 M, pH 4.5) and chloramine T (70 µL, 100 mM) to create a TMB+ substrate. After vortexing and dark incubation (2 hours, 25 °C), peroxidase enzyme (25 U) was added before aliquoting and storage at –20 °C. Working solutions combined TMB+ with acetic acid buffer (0.05 M, pH 5.8) in darkness. Serum samples (10 µL) were reacted with 200 µL of working solution in ELISA plates during 12-minute 37 °C incubations, terminated by the addition of 2N HCl. Optical density measurements at 450 nm (reference wavelengths 570/620 nm) were converted to Hamidi-Koliakos (HK) units through interpolation from H2O2-derived standard curves.

The investigation evaluated primary outcomes encompassing DPN symptomatology, neuropathy severity, and serum PAB, with sexual satisfaction serving as the secondary endpoint. Data collection utilized an eight-section instrument comprising (1) eligibility criteria verification; (2) demographic profiling (age, gender, marital status, income level, education level, employment status, number of family members, place of residence, medication use, medical history, weight, height, and BMI); (3) the Michigan Neuropathy Screening Instrument (MNSI); (4) the Toronto Clinical Scoring System (TCSS) for neuropathy severity; (5) the Larson Sexual Satisfaction Questionnaire (LSSQ); (6) biochemical test documentation; (7) medication adherence through daily intake logs; and (8) adverse event monitoring. Psychometric validation of the demographic instrument involved iterative refinement through content and face validity assessments by a 10-expert panel, ensuring construct alignment and cultural appropriateness. Analytical standardization was achieved through uniform protocols: single-operator biochemical assays using identical equipment and reagent batches (Lot-Controlled Single-Kit Methodology) to minimize inter-assay variability.

The MNSI operationalizes DPN assessment through dual modalities: a 15-item

self-reported symptom inventory (a score

The TCSS, originally developed by Perkins et al. [42], has demonstrated

cross-cultural validity through prior psychometric evaluations in Iranian

populations. This instrument utilizes a 19-point scale to grade diabetic

neuropathy severity. Diagnostic thresholds are stratified into three categories:

0–6 (mild neuropathy), 7–13 (moderate neuropathy), and

The instrument comprises 25 items employing a 5-point Likert scale (1: never to

5: always), yielding a total score range of 25–125. Sexual satisfaction is

stratified into four categories: dissatisfaction (

A priori power analysis via G*Power 3.1.2 incorporated parameters from Ahrary

et al. [40]: neuropathy symptom reduction (

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 21 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) through a hierarchical analytical framework adhering to modified

intention-to-treat principles. Normality assumptions were verified for each

interventional group using Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests, with

Levene’s test confirming variance homogeneity. Analytical procedures encompassed:

intergroup comparisons via

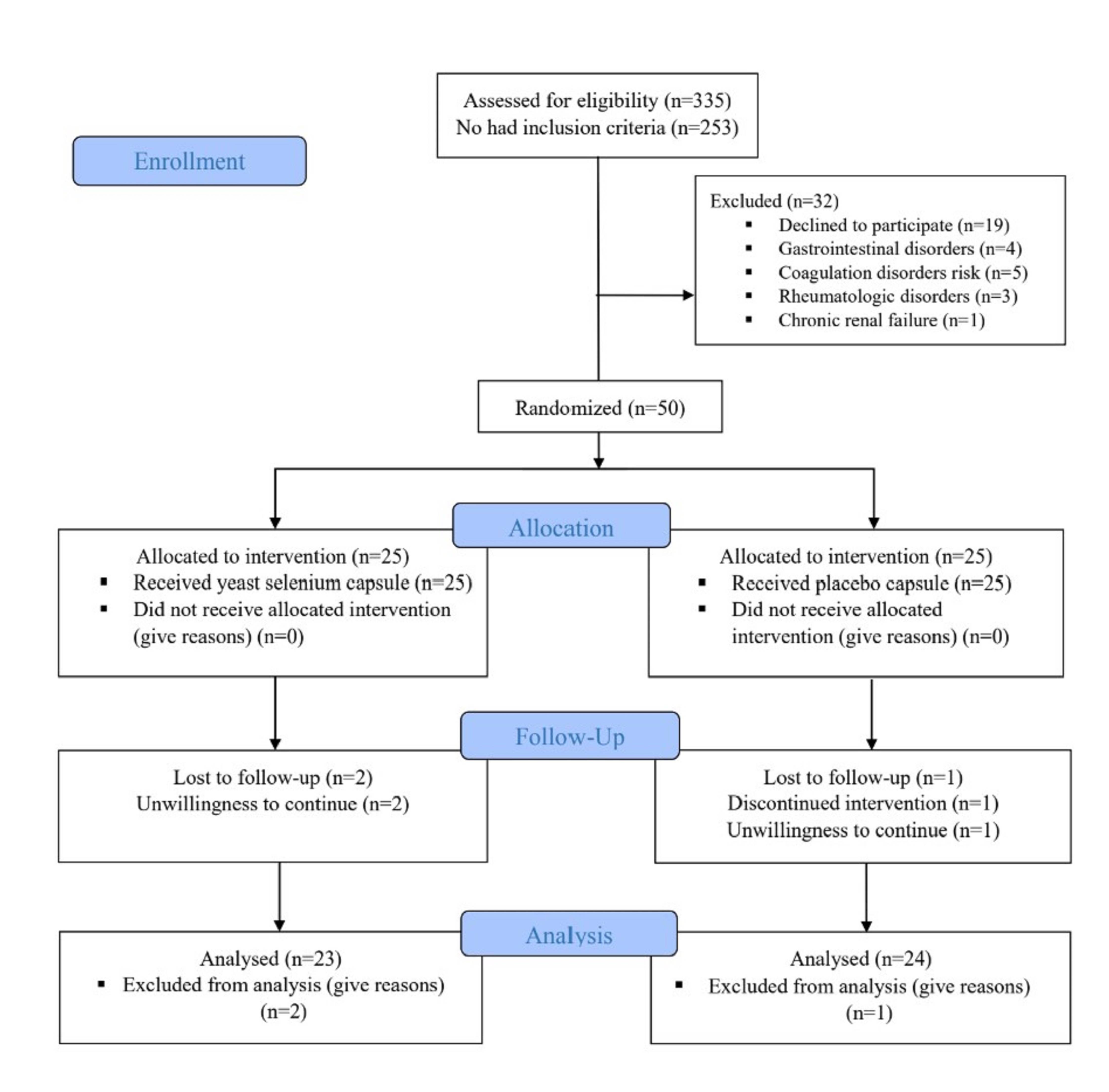

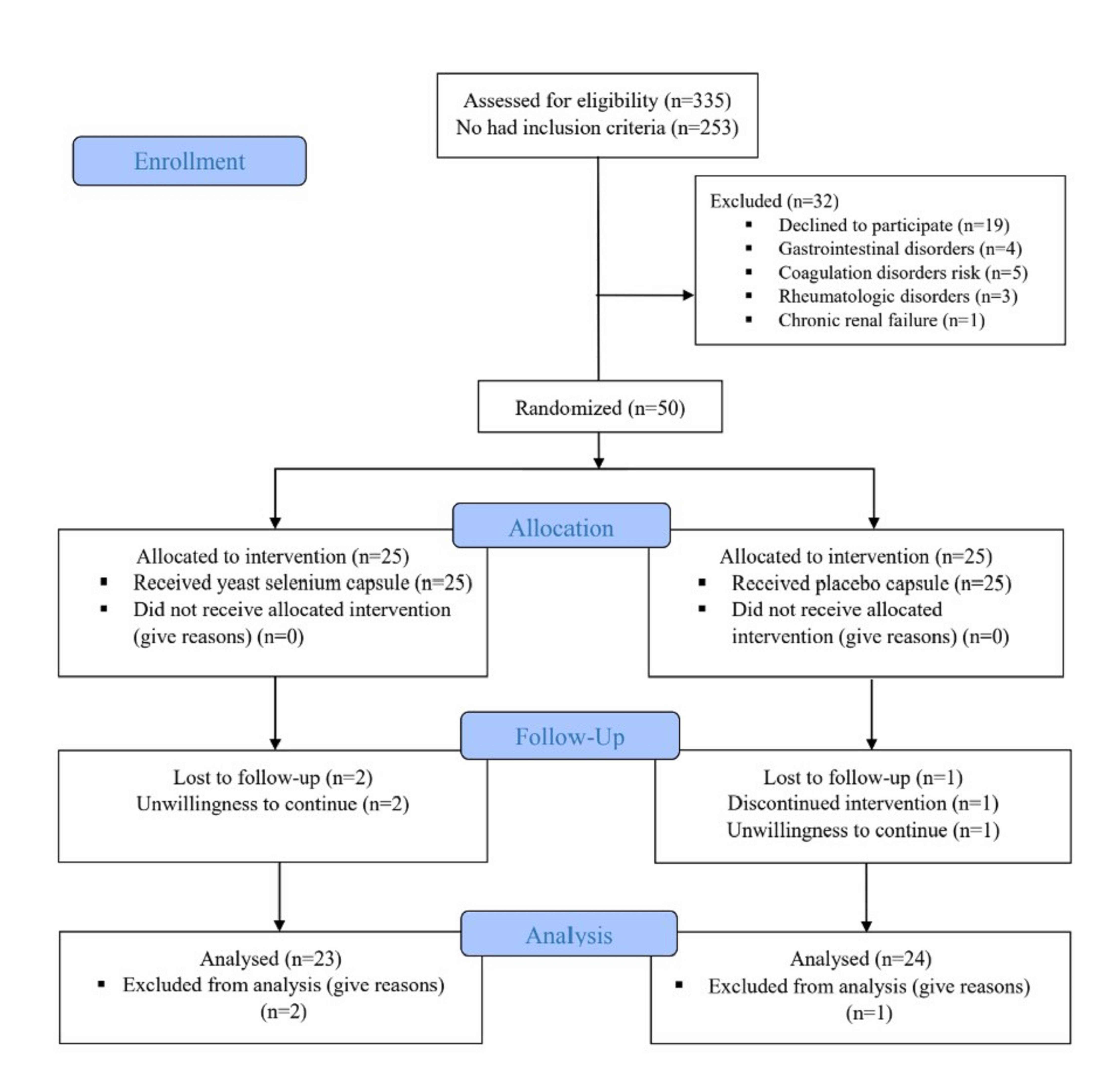

Participant recruitment occurred between April 21, 2021, and October 22, 2024, with the follow-up period concluding on December 22, 2024. A total of 335 individuals with diabetes were screened. Of these, 253 did not meet the inclusion criteria, and 32 were excluded due to unwillingness to participate (n = 19), digestive disorders (n = 4), coagulation risks (n = 5), rheumatological conditions (n = 3), or chronic renal failure (n = 1). The remaining 50 eligible participants were randomized into two groups (25 per group). During the 8-week intervention, two participants in the organic selenium group and one in the placebo group withdrew due to unwillingness to continue. Final analysis included 23 participants in the selenium group and 24 in the placebo group (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The flow diagram of study.

Table 1 summarizes demographic and clinical characteristics. No statistically

significant differences were observed between groups in terms of sex, age,

marital status, residence, education, income, employment, weight, or BMI (all

p

| Characteristics | Selenium | Placebo | p | |

| n = 25 | n = 25 | |||

| n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Age (years) | 0.316¥ | |||

| 40–50 | 7 (28.0) | 6 (24.0) | ||

| 51–60 | 9 (36.0) | 5 (20.0) | ||

| 61–70 | 9 (36.0) | 14 (56.0) | ||

| Gender | 0.551f | |||

| Female | 15 (60.0) | 18 (72.0) | ||

| Male | 10 (40.0) | 7 (28.0) | ||

| Habitation | 1.000f | |||

| City | 23 (92.0) | 24 (96.0) | ||

| Country | 2 (8.0) | 1 (4.0) | ||

| Marriage | 1.000f | |||

| Single | 5 (20.0) | 6 (24.0) | ||

| Married | 20 (80.0) | 19 (76.0) | ||

| Education | 0.180€ | |||

| Illiterate | 5 (20.0) | 11 (44.0) | ||

| Under diploma | 15 (60.0) | 11 (44.0) | ||

| Diploma and higher | 5 (20.0) | 3 (12.0) | ||

| Occupation | 0.498¥ | |||

| Home wife | 14 (56.0) | 18 (72.0) | ||

| Unoccupied | 3 (12.0) | 2 (8.0) | ||

| Occupied | 8 (32.0) | 5 (20.0) | ||

| Family income | 0.382€ | |||

| Sufficient | 3 (12.0) | 1 (4.0) | ||

| Rather sufficient | 9 (36.0) | 9 (36.0) | ||

| Insufficient | 13 (52.0) | 15 (60.0) | ||

| Weight (kg)/Mean |

78.6 |

74.6 |

0.353* | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.697¥ | |||

| Normal (18.5–25.9 kg/m2) | 3 (12.0) | 5 (20.0) | ||

| Overweight (25–29.9 kg/m2) | 10 (40.0) | 8 (32.0) | ||

| Obese ( |

12 (48.0) | 12 (48.0) | ||

| Type of diabetes/Type II | 25 (100.0) | 25 (100.0) | 1.000f | |

| FBS (mg/dL) | 180.3 (51.2) | 150.0 (47.7) | 0.035* | |

| Duration of DPN (years)/Mean |

13.5 |

14.6 |

0.571* | |

| Taking diabetic medications | 0.889f | |||

| Gloripa | 6 (24.0) | 6 (24.0) | ||

| Gliclazide | 5 (20.0) | 6 (24.0) | ||

| Metformin+gloripa | 4 (16.0) | 3 (12.0) | ||

| Metformin | 4 (16.0) | 5 (20.0) | ||

| Insulin | 4 (16.0) | 4 (16.0) | ||

| Insulin+gliclazide | 2 (8.0) | 1 (4.0) | ||

| Smoking | 0.167¥ | |||

| Never | 19 (76.0) | 23 (92.0) | ||

| Current smoker | 3 (12.0) | - | ||

| Past smoker | 3 (12.0) | 2 (8.0) | ||

| Having hypertension/yes | 19 (76.0) | 18 (72.0) | 1.000f | |

| Having hyperlipidemia/yes | 20 (80.0) | 20 (80.0) | 1.000f | |

DPN, diabetic peripheral neuropathy; BMI, body mass index; MNSI, Michigan

neuropathy screening instrument; A score of

Table 2 details diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN) symptom scores using the

Michigan Neuropathy Screening Instrument (MNSI). Baseline total scores were

similar (8.6

| Variable | Selenium (n = 25) | Placebo (n = 25) | aMD (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||||

| Total MNSI (0–15) | |||||

| Baseline | 8.6 (1.5) | 8.2 (1.2) | - | 0.271* | |

| After 2 month | 6.5 (2.0) | 7.1 (1.7) | –0.92 (–1.9 to 0.10) | 0.077§ | |

| p-value¥ | 0.001 | ||||

| Total MNSI examination (0–8) | |||||

| Baseline | 2.6 (1.1) | 2.5 (0.9) | - | 0.667* | |

| After 2 month | 1.8 (1.2) | 1.8 (1.0) | –0.01 (–0.65 to 0.63) | 0.969§ | |

| p-value¥ | 0.004 | 0.008 | |||

| MNSI exam 1/Disordered | n (%) | n (%) | OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Baseline | 13 (52.0) | 15 (60.0) | - | 0.776f | |

| After 2 month | 7 (28.0) | 9 (36.0) | 0.84 (0.23 to 3.02) | 0.792± | |

| p-value¥ | 0.029 | 0.008 | |||

| MNSI exam 2/Disordered | OR (95% CI) | p-value | |||

| Baseline | 7 (28.0) | 5 (20.0) | - | 0.742f | |

| After 2 month | 3 (12.0) | 3 (12.0) | 0.79 (0.12 to 4.98) | 0.792± | |

| p-value¥ | 0.125 | 0.688 | |||

| MNSI exam 3/Disordered | OR (95% CI) | p-value | |||

| Baseline | 20 (80.0) | 19 (76.0) | - | 1.000f | |

| After 2 month | 15 (60.0) | 16 (64.0) | 0.78 (0.24 to 2.58) | 0.687± | |

| p-value¥ | 0.125 | 0.508 | |||

| MNSI exam 4/Disordered | OR (95% CI) | p-value | |||

| Baseline | 25 (100) | 23 (92.0) | - | 0.490f | |

| After 2 month | 18 (72.0) | 18 (72.0) | 1.12 (0.32 to 3.91) | 0.853± | |

| p-value¥ | 0.016 | 0.180 | |||

* Independent t-test, aMD (95% CI): adjusted Mean difference (95% confidence interval). § ANCOVA adjusted for baseline values, age, and sex, ¥ Paired Samples t-test, ± Logistic regression adjusted for baseline values, age, and sex, f Fishers exact test. The bold p-values indicate the statistical significance. MNSI is a two-part instrument, with the first part consisting of 15 questions to be completed by the individual and the second part consisting of 4 questions to be completed by a professional after examination. In the first part, the responses are summed to obtain a total score. A score greater than or equal to 7 is considered abnormal. The range of scores for Total MNSI and Total MNSI examination is 0–15 and 0–8, respectively.

Table 3 presents neuropathy severity outcomes using the Toronto Clinical Scoring

System (TCSS). Baseline scores indicated moderate severity in both groups (12.2

| Variable | Selenium (n = 25) | Placebo (n = 25) | aMD (95% CI) | p-value± | ||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |||||

| Total TCSS (0–19) | ||||||

| Baseline | 12.2 (3.2) | 11.2 (2.9) | - | 0.259* | ||

| After 2 month | 9.5 (4.8) | 10.2 (4.0) | –1.34 (–3.49 to 0.81) | 0.214§ | ||

| p-value¥ | 0.002 | 0.106 | ||||

| Symptom scores (0–6) | ||||||

| Baseline | 4.5 (1.5) | 4.5 (1.2) | - | 0.992* | ||

| After 2 month | 3.4 (2.2) | 4.2 (1.7) | –0.71 (–1.68 to 0.26) | 0.147§ | ||

| p-value¥ | 0.015 | 0.181 | ||||

| Reflex scores (0–8) | ||||||

| Baseline | 4.3 (2.5) | 3.6 (2.5) | - | 0.319* | ||

| After 2 month | 2.9 (2.6) | 3.6 (2.6) | –0.71 (–2.19 to 0.77) | 0.337§ | ||

| p-value¥ | 0.092 | 1.0 | ||||

| Sensory test scores (0–5) | ||||||

| Baseline | 3.4 (1.1) | 3.2 (0.9) | - | 0.456* | ||

| After 2 month | 2.6 (1.2) | 2.7 (1.2) | –0.17 (–0.87 to 0.54) | 0.636§ | ||

| p-value¥ | 0.017 | 0.045 | ||||

| TCSS severity | n (%) | n (%) | p-value± | |||

| Baseline | ||||||

| Mild | 1 (4.0) | 2 (8.0) | - | 0.311 | ||

| Moderate | 15 (60.0) | 17 (68.0) | ||||

| Severe | 9 (36.0) | 6 (24.0) | ||||

| After 2 month | ||||||

| Mild | 6 (25.0) | 4 (17.4) | - | 0.658 | ||

| Moderate | 13 (54.2) | 15 (62.2) | ||||

| Severe | 5 (20.8) | 4 (17.4) | ||||

TCSS is a screening tool for diabetic peripheral neuropathy, and correlates with diabetic neuropathy severity. Maximum TCNS is 19 points. Symptom scores graded as 0 = absent, 1 = present; Sensory test scores graded as 0 = normal, 1 = abnormal, Reflexes graded as 0 = normal, 1 = reduced, 2 = absent. Scores of 0–6 indicate mild neuropathy, 7–13 indicate moderate neuropathy, and scores above 13 indicate severe sensory disturbances.

* Independent t-test, aMD (95% CI): adjusted Mean difference (95% confidence interval). § ANCOVA adjusted for baseline values, age, and sex, ¥ Paired Samples t-test, ± Mann-Whitney U. The bold p-values indicate the statistical significance.

Table 4 outlines PAB results. Baseline serum PAB levels were comparable (p = 0.424). Post-intervention, selenium supplementation significantly reduced PAB levels (p = 0.001), though intergroup differences were nonsignificant (aMD: –32.1; 95% CI: –66.02 to 1.87; p = 0.063).

| Variable | Selenium (n = 25) | Placebo (n = 25) | aMD (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||||

| PAB (HK) | |||||

| Baseline | 192.9 (34.5) | 182.4 (55.6) | - | 0.424* | |

| After 2 month | 134.3 (49.6) | 163.7 (45.7) | –32.07 (–66.02 to 1.87) | 0.063§ | |

| Mean change (95% CI) | –58.6 (–89.3 to –28.1) | –18.6 (–45.0 to 7.8) | |||

| p-value¥ | 0.001 | 0.159 | |||

* Independent t-test, aMD (95% CI): adjusted Mean difference (95% confidence interval). § ANCOVA adjusted for baseline values, age, and sex. ¥ Paired Samples t-test. The bold p-value indicates the statistical significance. The bold p-values indicate the statistical significance.

Table 5 details sexual satisfaction outcomes. Baseline scores reflected moderate satisfaction in both groups (p = 0.964). Post-intervention, placebo group scores declined to low satisfaction (p = 0.004), while the selenium group maintained moderate levels (p = 0.277). Final satisfaction scores were higher in the selenium group (aMD: 8.51; 95% CI: 0.74–16.28; p = 0.033), with 84.2% of selenium participants reporting moderate satisfaction and 75% of placebo participants reporting low satisfaction (p = 0.001).

| Variable | Selenium (n = 20) | Placebo (n = 19) | aMD (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||||

| Sexual satisfaction score (25–125) | |||||

| Baseline | 85.1 (13.2) | 84.9 (16.2) | - | 0.964* | |

| After 2 month | 81.1 (13.4) | 73.5 (9.2) | 8.51 (0.74 to 16.28) | 0.033§ | |

| p-value¥ | 0.277 | 0.004 | |||

| Sexual satisfaction rate | n (%) | n (%) | p-value± | ||

| Baseline | |||||

| No ( |

- | - | 0.771 | ||

| Low (51–75) | 3 (15.0) | 6 (31.6) | |||

| Moderate (76–100) | 15 (75.0) | 9 (47.4) | |||

| High (101–125) | 2 (10.0) | 4 (21.1) | |||

| After 2 months | |||||

| No ( |

- | - | 0.001± | ||

| Low (51–75) | 4 (20.0) | 16 (84.2) | |||

| Moderate (76–100) | 15 (75.0) | 2 (10.5) | |||

| High (101–125) | 1 (5.0) | 1 (5.3) | |||

The higher the total score, the more sexual satisfaction, aMD (95% CI): mean difference (95% confidence interval), * Independent t-test, § ANCOVA adjusted for baseline, age, BMI, ¥ paired Samples t-test, ± Mann-Whitney U. The bold p-values indicate the statistical significance.

Intervention satisfaction differed marginally: 43.4% of selenium and 25% of placebo participants reported being satisfied, while 52.2% vs. 58.3% were neutral, and 8.7% vs. 16.7% were dissatisfied (p = 0.445). Adverse events included mild diarrhea, abdominal pain, and dizziness (4 in the selenium group, 3 in the placebo group), none requiring discontinuation. Capsule counting from the returned medications and review of the controlling daily medication checklist showed that medication compliance exceeded 90% in both groups

The analysis revealed that both groups demonstrated comparable baseline total MNSI scores exceeding established clinical thresholds. Post-intervention assessment at eight weeks showed statistically significant reductions in total scores for both the selenium-enriched yeast-supplemented and placebo groups. While the selenium group exhibited greater mean decreases, achieving post-treatment scores below clinical cutoffs, intergroup comparisons revealed no statistically significant differential effects. Longitudinal evaluation of four MNSI subdomains (symptom inventory, appearance, sensory perception, and reflex testing) similarly showed non-significant between-group differences at baseline and post-intervention. These findings suggest comparable therapeutic trajectories despite numerical advantages in the experimental group. Neuropathy severity evaluation using TCSS demonstrated moderate mean total scores at baseline in both groups. Post-intervention, the selenium group showed significant intragroup reductions in neuropathy severity. The organic selenium group exhibited significant decreases in PAB index values during treatment and statistically greater improvements in sexual satisfaction metrics compared to placebo controls.

Pain pathophysiology involves complex interactions between oxidative stress and Ca2+ signaling. Mitochondrial dysfunction caused by Ca2+-induced membrane depolarization generates ROS, which is modulated by antioxidants including selenium. As a GPx cofactor and selenoprotein component, selenium exerts neuroprotective effects by regulating ROS overproduction, inflammation, and Ca2+ overload in conditions like diabetic neuropathy, allodynia, and nociception. Ca2+ influx occurs through transient receptor potential (TRP) channels (TRPA1, TRPM2, TRPV1, TRPV4), many of which are activated by oxidative stress to induce peripheral pain. Recent studies indicate that selenium modulates peripheral pain via TRP channel inhibition in dorsal root ganglia [45]. Song and Lin [46] demonstrated that selenium upregulates the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2/heme oxygenase-1Nrf2/HO-1 pathway to inhibit oxidative stress and p38 MAPK phosphorylation, enhancing Schwann cell proliferation and peripheral nerve regeneration.

Current models characterize pain as a multifactorial process involving oxidative stress-mediated neural cascades. Mitochondrial dysfunction from Ca2+-induced ROS generation is central to nociceptive processing. Selenium’s therapeutic potential arises from its dual role in GPx activation and selenoprotein synthesis, mitigating oxidative damage in chronic pain [47]. Altuhafi et al. [48] delineated oxidative stress mechanisms in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) pathogenesis, where chronic hyperglycemia drives free radical production via glucose autoxidation and impairs antioxidant systems. This redox imbalance causes cellular organelle damage, elevated lipid peroxidation, and insulin resistance [49].

Diabetic metabolic dysregulation increases mitochondrial ROS in pancreatic

Huo et al. [52] conducted a meta-analysis of 14 randomized controlled

trials (n = 1384 participants) investigating nutraceutical interventions for DPN.

Their systematic review identified three high-quality trials demonstrating that

vitamin and antioxidant supplementation significantly enhanced sural nerve

sensory nerve conduction velocity (SNCV). Furthermore, pooled data from seven

trials (n = 758) suggested improved peroneal nerve motor nerve conduction

velocity (MNCV), while four studies reported analogous enhancements in median

nerve MNCV. These findings align empirically with our observations regarding

selenium’s capacity to mitigate DPN severity. Complementary mechanistic evidence

emerges from Aydın and Nazıroğlu [53], who demonstrated that

streptozotocin (STZ)-induced TRPM7 channel activation exacerbates neuropathic

pain and apoptotic pathways in murine models. Crucially, selenium administration

attenuated TRPM7-mediated neurotoxicity, mirroring our findings of selenium’s

neuroprotective efficacy. Jafari et al. [54] further corroborated this

therapeutic potential through in vitro experiments showing that selenium

co-treatment significantly reduced vincristine-induced cytotoxicity in PC12

neuronal cells (p

Ayaz and Kaptan [30] provided electrophysiological evidence that sodium selenite intervention ameliorates diabetes-induced neural conduction abnormalities, including prolonged signal transmission latency, increased action potential amplitude (32% vs. diabetic controls), and restoration of fast/slow fiber conduction velocity distributions to age-matched normative ranges. These data synergize with Xu et al.’s clinical correlation analysis [29], which identified low selenium status as an independent risk factor for diabetic polyneuropathy progression in type 2 diabetes cohorts. At the molecular level, Nazıroğlu et al. [47] postulated that selenium’s antinociceptive mechanism involves TRP channel modulation in dorsal root ganglia, potentially disrupting nociceptive signaling cascades. Collectively, these multidisciplinary findings substantiate selenium’s dual role as both a redox modulator and ion channel regulator in diabetic neuropathy pathogenesis, providing mechanistic context for its observed clinical benefits in DPN management.

Teimouri et al. [55] conducted a double-blind, randomized,

placebo-controlled clinical trial to investigate the therapeutic efficacy of

selenium supplementation on psychosexual outcomes. Their findings demonstrated

clinically significant amelioration of core premature ejaculation symptomatology

in the intervention group compared to placebo controls (p

One of the limitations of our study was the restricted sample size, which future

research should address through larger cohorts. A key strength was the

triple-blind design, enhancing methodological rigor. Additional strengths

included standardized examinations performed by an experienced specialist,

precise follow-up timing to ensure timely patient referrals, and the use of

organic selenium with high bioavailability and lower toxicity. However, the

absence of speciation analysis introduces uncertainty regarding the supplement’s

composition and bioactivity, necessitating such analyses in future trials to

clarify bioavailability and therapeutic efficacy. Larger studies should also

characterize selenium species and investigate dose-response relationships. This

study did not evaluate key inflammatory biomarkers, such as IL-6, IL-8, and

TNF-

The 8-week intervention yielded significant therapeutic outcomes across both groups. Post-treatment evaluation revealed clinically meaningful reductions in MNSI scores for both groups, though intergroup comparisons showed no statistically significant differential effect. Neuropathic severity assessments using the TCSS demonstrated a 38% baseline-to-post-intervention score reduction exclusively in the selenium group. Psychosexual outcomes diverged markedly between groups: placebo recipients exhibited a progressive decline in sexual satisfaction metrics to subclinical thresholds by week 8, whereas the selenium group maintained baseline satisfaction levels, achieving statistically superior terminal scores. Selenium supplementation also significantly reduced the PAB index. These findings suggest that selenium may simultaneously mitigate neuropathic progression and preserve sexual function in diabetic populations, though its therapeutic effect on neuropathy outcomes requires further investigation through larger trials with speciation analysis, extended durations, and dose-response characterization.

The datasets supporting this study’s findings are available from corresponding author per request.

MG and AFK were responsible for drafting the protocol, data collection, data analysis, and interpretation and writing of the final manuscript. MM was responsible for drafting the protocol, project administration, data analysis and interpretation, and editing the final version of the manuscript. SGR, PBM and AO were involved in the acquisition of data and critically reviewed the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (IR.TBZMED.REC.1401.374). Researchers ensured protocol adherence through institutional authorization and strict compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki (1964) and its subsequent amendments. Prior to the intervention, participants received full disclosure of the study objectives, methodologies, potential risks/benefits, and withdrawal rights through direct researcher communication, followed by the acquisition of written informed consent. This trial was registered at the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT20131009014957N10, https://trialsearch.who.int/Trial2.aspx?TrialID=IRCT20131009014957N10).

The authors extend their gratitude to all study participants for their contributions. Additionally, they acknowledge the institutional support provided by the Research Department of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, which facilitated the completion of this research endeavor.

The Vice-Chancellor for Research and Technology, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences has funded the original research (Grant No: 69271).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

The authors utilized DeepSeek (DeepSeek-V3) for scientific English language editing to improve the clarity and grammar of this manuscript. Following AI-assisted editing, the authors thoroughly reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the published work.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.