1 Department of Gastroenterology, Hangzhou TCM Hospital of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University (Hangzhou Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine), 310013 Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

2 Department of Nephrology, Hangzhou TCM Hospital of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University (Hangzhou Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine), 310013 Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

Abstract

Calcium plays a central role in gastrointestinal (GI) physiology through regulating smooth muscle contractility, acid secretion, epithelial barrier integrity, and immune signaling. The dysregulation of calcium homeostasis has been increasingly implicated in the pathogenesis of GI disorders, including colorectal cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, peptic ulcer, and pancreatitis. Specifically, aberrant calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR) signaling has emerged as a critical molecular mechanism in colorectal tumorigenesis; meanwhile, calcium-mediated pathways influence gastric acid production and intestinal motility. This review critically evaluated recent advances in calcium signaling within the GI tract, highlighting the crosstalk involved with the gut microbiota and the roles of downstream effectors, including transient receptor potential vanilloid type 6 and store-operated calcium entry. This review also examined the therapeutic implications of calcium supplementation across various GI conditions, including bioavailability challenges under different disease states and nutrient interactions involving vitamin D and phosphate. Our review further addresses the role of calcium in mucosal immunity, the clinical relevance of hypocalcemia in GI diseases, and the potential of microbiome-guided nutritional interventions. However, despite growing mechanistic insights, considerable gaps remain in understanding host–microbiota–calcium interactions, genotype-specific responses to calcium, and long-term clinical outcomes. Thus, future research should clarify the dose–response relationships, stratify patient populations by CaSR polymorphisms and microbiome profiles, and establish precision strategies for calcium-based interventions in digestive health.

Keywords

- calcium

- gastrointestinal disorders

- gut microbiota

- CaSR

- calcium supplements

Calcium, the most abundant inorganic element in the human body, plays both fundamental and regulatory roles in various physiological processes. Approximately 98%–99% of calcium is stored in the skeleton as hydroxyapatite crystals, whereas the remainder circulates in the blood and soft tissues, where it is involved in intracellular signaling, neuromuscular excitability, and hormonal regulation. Calcium homeostasis is maintained through the coordinated actions of parathyroid hormone (PTH), active vitamin D [1,25(OH)2D3], and calcitonin, which collectively regulate intestinal absorption, renal reabsorption, and skeletal mobilization.

In the gastrointestinal (GI) system, calcium is not only primarily absorbed but also actively contributes to smooth muscle contraction [1], gastric acid secretion [2], epithelial barrier maintenance [3], and immune response [4]. Disruptions in calcium homeostasis have been closely linked to various GI diseases, including gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) [5], peptic ulcer disease (PUD) [6], acute pancreatitis (AP) [7], inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [4], and colorectal cancer (CRC) [8]. In these contexts, calcium is involved in both pathogenesis and therapeutic modulation. Recently, the widespread adoption of Western dietary patterns—characterized by high fat and low fiber intake—combined with an increased use of acid-suppressive agents, including proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs), has impaired calcium absorption and disrupted the gut barrier integrity, with high-fat diets specifically inducing intestinal inflammation and affecting gut permeability [9, 10].

Of particular interest is the emerging recognition of a bidirectional relationship between calcium and the gut microbiota, which has been underexplored in prior mechanistic reviews. Microbial-derived short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), including butyrate and propionate, can modulate the expression of epithelial calcium transporters, such as transient receptor potential vanilloid type 6 (TRPV6) and plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase 1b (PMCA1b), thereby affecting calcium absorption [11]. Calcium intake and supplementation can reshape microbial diversity and metabolic profiles, potentially altering barrier function and inflammatory status. Dysbiosis—frequently observed in IBD, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), and post-gastrectomy states—may impair calcium solubility, disrupt luminal ion gradients, and reduce transporter availability, ultimately decreasing absorption efficiency and compromising the systemic calcium balance [12, 13]. However, the clinical validation of this complex microbiota–calcium–host interaction remains limited, representing a critical gap in the current understanding of GI calcium physiology.

Recent animal and human studies have highlighted the potential of specific nutritional interventions in modulating calcium status. The combined administration of probiotics (e.g., Lactobacillus acidophilus) and phytoestrogens (e.g., daidzein and tempeh) have shown varying effects on the serum calcium levels, calcium transporter expression (e.g., TRPV5, TRPV6), and bone metabolism biomarkers in ovariectomized rats and postmenopausal women [14, 15, 16]. Some combinations appear to mimic bisphosphonates by enhancing calcium retention and regulating bone turnover, whereas others have shown limited or inconsistent effects in the absence of estrogenic or mineral co-factors [17, 18]. Moreover, in vitro digestion models suggest that probiotics may enhance calcium bioaccessibility from both organic and inorganic salts, whereas certain soybean-derived compounds may inhibit calcium absorption under specific conditions [19]. These findings suggest the potential synergistic or antagonistic mechanisms linking functional food, calcium transport efficiency, and the gut–bone axis, warranting further systematic investigations [20, 21].

Calcium acts through specific signaling nodes, including the calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR). The CaSR, a G-protein-coupled receptor expressed primarily in the parathyroid glands, kidneys, and bones, has emerged as a key regulator of intestinal permeability and mucosal immune responses [22]. However, there are limited studies on CaSR polymorphisms and downstream signaling in human GI diseases. Similarly, the metabolic interplay between calcium and other nutrients—including vitamin D, phosphate (PO43-), and magnesium—and their combined influence with vitamin D receptor (VDR) genotypes have not been adequately characterized in clinical contexts [23].

Although prior reviews have independently addressed calcium metabolism, microbial influence, or supplementation strategies, only a few studies have performed an integrated assessment of the molecular pathways, regulatory factors, and intervention strategies in the context of GI disorders. The present review aimed to fill this gap by focusing on the following four main areas: (1) mechanistic insights into calcium signaling in GI motility, secretion, barrier integrity, and inflammation, including the roles of CaSR and store-operated calcium entry (SOCE); (2) alterations in calcium absorption dynamics under pathological GI conditions; (3) bidirectional interactions between the gut microbiota and calcium in healthy individuals and patients with diseases; and (4) nutritional and pharmacological interventions, including the differences in calcium formulations, probiotic-based therapies, and gene–microbiota–dietary synergies.

The present paper also highlights major research challenges, including the translational gaps between bench and bedside, population heterogeneity, and methodological limitations, and proposes future directions to advance personalized calcium-based nutritional strategies for GI disorders.

Calcium in humans originates from two distinct sources: endogenous and exogenous

sources. The endogenous pool, comprising skeletal reserves (

Following oral ingestion, insoluble calcium salts [e.g., calcium

carbonate (CaCO3) and calcium oxalate (CaC2O4)] undergo

acid-mediated solubilization in the gastric lumen, where hydrochloric acid (HCl)

converts them into soluble Ca2+ ions that become bioaccessible

(stomach-soluble but not yet absorbed) [24]. Concurrently, HCl activates the

conversion of pepsinogen to pepsin, which proteolytically cleaves dietary

proteins and liberates calcium-binding amino acids that enhance calcium

solubility. This digestive process is modulated by the following dietary factors:

acidic foods (pH

Following gastric processing, calcium ions (Ca2+) progress to the small intestine, which is the principal site of calcium absorption. Two distinct mechanisms mediate intestinal calcium absorption: (1) transcellular active transport, primarily localized to the duodenum and proximal jejunum where luminal pH (~6.0) optimizes the function of the TRPV6 channel, and (2) paracellular passive diffusion, predominant in the ileum under luminal calcium overload conditions [27].

2.2.2.1 Transcellular Active Transport Mechanism

The transcellular pathway involves the following three sequential steps: (1)

apical entry via the TRPV6 channels; (2) cytosolic shuttling bound to the

calcium-binding protein calbindin-D9k; and (3) basolateral extrusion through

PMCA1b and Na+/Ca2+ exchanger [28]. This transport cascade is

critically regulated by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 [1,25(OH)2D3],

which upregulates the TRPV6 and calbindin expressions through VDR-mediated

genomic signaling. The current clinical studies have demonstrated that the

intestinal lesions in patients with Crohn’s disease lead to the downregulation of

TRPV6 expression for

2.2.2.2 Paracellular Passive Diffusion Mechanism

The paracellular route utilizes tight junction (TJ) complexes containing

occludin and claudin family proteins (particularly claudin-2/12), which form

cation-selective pores permitting passive calcium flux along electrochemical

gradients [33]. In patients with IBD, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-

The gut microbiota promote the fermentation of dietary fiber, leading to increased SCFAs levels in the intestinal lumen. This process lowers the luminal pH, thereby enhancing the solubility of poorly soluble calcium salts, including CaCO3 and dicalcium phosphate [36]. In mouse models, SCFAs upregulate TRPV6 mRNA expression in human colonic epithelial cells, thereby promoting active calcium transport [37]. More recently, the use of radiolabeled 45Ca in mice revealed that SCFAs—particularly butyrate—can enhance calcium flux in the cecum by upregulating the calcium transporters, including TRPV6 and the Na+/H+ exchanger NHE3 [11]. Therefore, in cases of dysbiosis or IBD, reduced SCFA levels may lead to the decreased expression of calcium transport proteins and impaired calcium absorption. Additionally, a previous study investigating gut–brain axis modulation in patients with autism spectrum disorder has reported that SCFAs may also indirectly improve the calcium uptake by regulating intestinal serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine) signaling [38].

Calcium transport and absorption are influenced differently at various stages of

life. During adolescence, the growth hormone (GH) and its physiological mediator

insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-1) play important roles in calcium absorption

and bone mass accumulation. GH/IGF-1-stimulated production of calcitriol may

increase distal calcium reabsorption by upregulating the TRPV5 channel expression

[39]. As a result, the calcium absorption capacity is considerably enhanced

during adolescence. Contrarily, in the elderly, calcium absorption decreases due

to several factors, including reduced serum 25(OH)D levels and decreased PTH

secretion [40, 41]. Estrogen exerts a more considerable effect on calcium

absorption. Estrogen reportedly regulates duodenal calcium absorption via the

differential effects of ER

Calcium absorption is also influenced by other metal ions. From a chemical perspective, phosphorus, as the primary mineral antagonist of calcium, can considerably inhibit intestinal calcium absorption by forming insoluble complexes. However, recent studies have found that, under high-phosphorus diets, varying levels of calcium intake do not markedly affect calcium absorption [44]. Magnesium plays an essential role in PTH synthesis and secretion, thereby indirectly regulating calcium homeostasis [45]. Other metal elements, including iron and zinc, compete with calcium for absorption in the intestine and may influence each other’s efficiency. Excessive iron uptake may lead to the accumulation of iron within intracellular vesicles or disrupt calcium signaling by competing for entry into these vesicles, thereby inhibiting calcium absorption. However, in animal models, iron supplementation helps correct iron-deficiency anemia, which can, in turn, enhances calcium absorption [46]. Zinc competes with calcium for binding sites on the apical membrane, but considerable interference with calcium absorption is only observed when the amount of zinc intake reaches 140 mg/day, particularly under conditions of low calcium intake (230 mg/day) [47].

Collectively, the GI system orchestrates calcium assimilation through spatially coordinated absorption mechanisms while integrating endocrine signals to preserve systemic calcium homeostasis.

With the ongoing advancement in GI research, the experimental tools for studying calcium transport mechanisms are evolving from classical models to systems with higher physiological relevance and dynamic controllability. The Ussing chamber system remains the gold-standard ex vivo model for assessing intestinal permeability and predicting human intestinal absorption and metabolism. It is widely used for evaluating transepithelial calcium transport in intestinal tissues [48, 49]. However, its limitations in cell-type specificity and inability to replicate the intestinal microenvironment restrict its utility for in-depth mechanistic studies.

To overcome these limitations, intestinal organoids have been introduced. Derived from stem cells, these three-dimensional structures recapitulate key features of the intestinal epithelium, offering greater physiological relevance. Organoids are particularly suited for genetic editing, hormonal stimulation assays, transcriptomic analyses, disease modeling, and drug screening [50, 51, 52]. Nevertheless, their traditional closed architecture poses challenges for the quantitative assessment of absorption. Building upon this, gut-on-a-chip technologies, which provide enhanced dynamic interaction and enable more accurate reproduction of intestinal drug absorption, have recently emerged. These systems allow the investigation of the impact of food matrices, bile acids, or inflammatory conditions on the gut microbiota and calcium transport under dynamic conditions [53, 54, 55].

Meanwhile, radioactive and fluorescent calcium tracing techniques offer mechanistic insights at the microscale. These methods enable subcellular resolution imaging of calcium channel activation, mitochondrial buffering, and endoplasmic reticulum (ER)–plasma membrane (PM) calcium coupling. For example, the use of the radioactive isotope 45Ca allows high-resolution quantification of intracellular calcium fluxes, facilitating the study of SOCE and mitochondrial calcium buffering [11].

Finally, the recent incorporation of AI-based modeling and algorithmic tools has further enhanced the ability of approaches to integrate multidimensional parameters and provide quantitative predictions.

Ca2+, beyond serving as a fundamental intracellular second messenger, functions as an integrative signaling hub coordinating the following three essential GI functions: smooth muscle motility, gastric acid secretion, and mucosal barrier maintenance. The regulatory actions of Ca2+ span multiple physiological levels, from rapid excitation–contraction coupling at the cellular level to the fine-tuning of glandular secretion and ultimately to the preservation of epithelial integrity at the tissue level. This highlights the multidimensional and hierarchical nature of calcium signaling and its role in systemic coordination across GI functions.

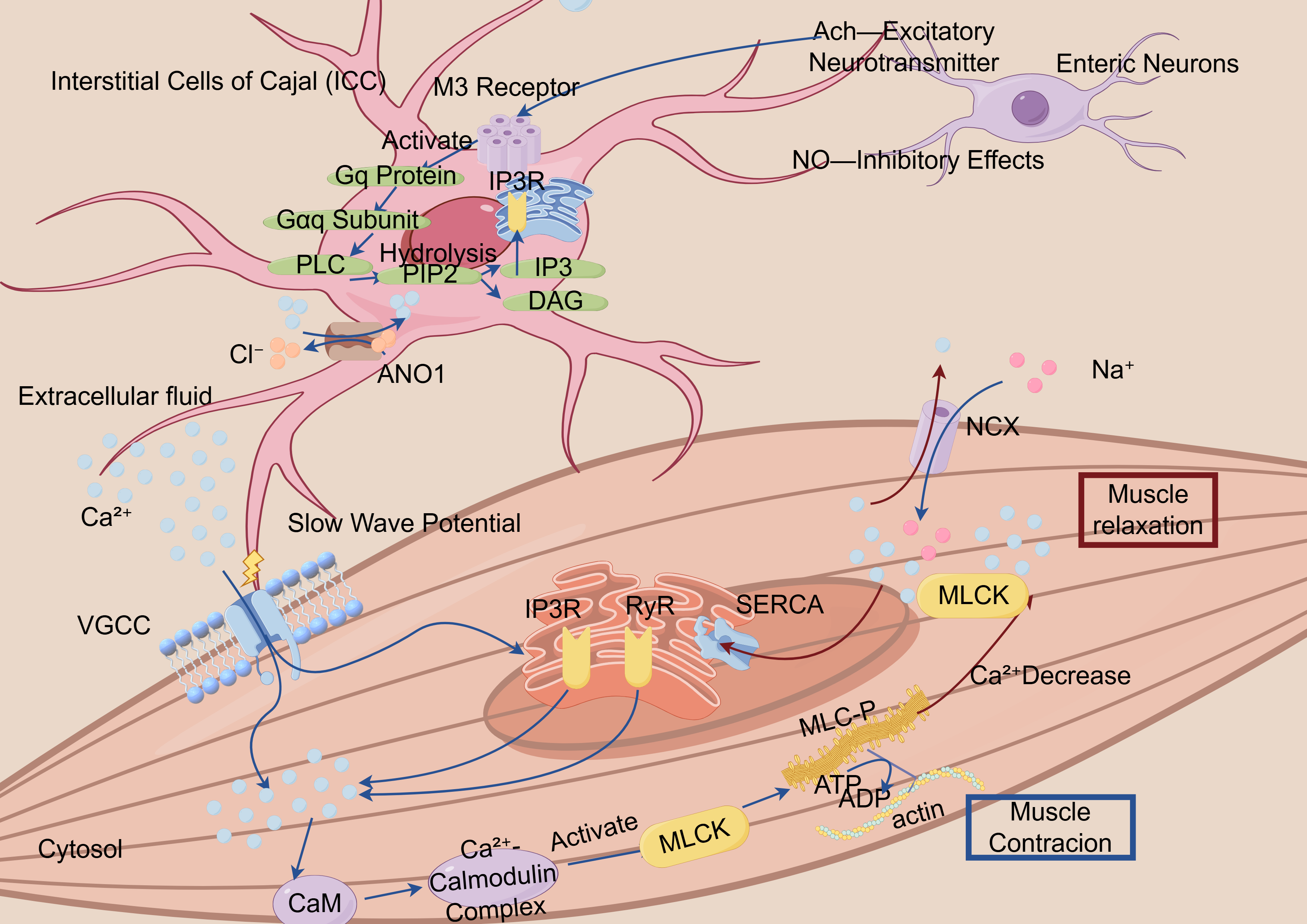

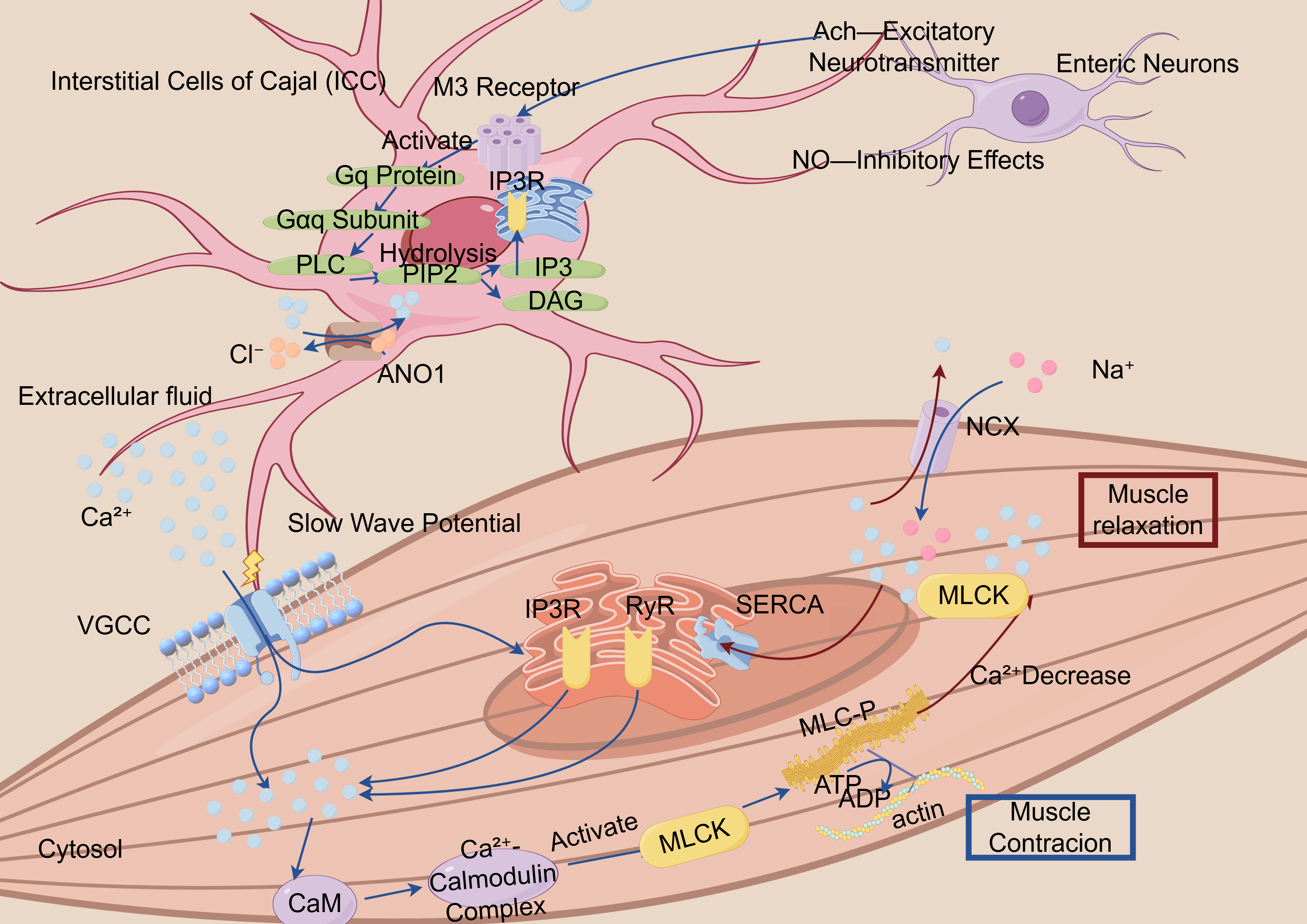

Ca2+ signaling orchestrates the contractile dynamics of the GI smooth

muscle through precisely coordinated molecular mechanisms. The elevation of

intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) and its interaction with

contractile proteins constitute the fundamental mechanism of smooth muscle

contraction. Increased [Ca2+]i is achieved through the following two primary

pathways: (1) transmembrane influx, membrane depolarization opens the

voltage-gated calcium channels, particularly the L-type and T-type channels,

permitting extracellular Ca2+ entry [56, 57]; and (2) intracellular release,

calcium-induced calcium release via the ryanodine receptors and inositol

1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor (IP3R) triggers Ca2+ efflux from the

sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) [58, 59]. The combined contributions of transmembrane

influx and SR release determine the [Ca2+]i dynamics, with the amplitude and

duration of calcium transients dictating the force and persistence of smooth

muscle contraction. As a ubiquitously expressed calcium decoder, calmodulin (CaM)

undergoes conformational changes upon binding four Ca2+ through its EF-hand

motifs (Kd = 10-6–10-7 M), forming a Ca2+-saturated complex that

docks into the autoinhibitory domain of myosin light chain kinase (MLCK), thereby

releasing a catalytic activity through steric displacement of regulatory

helices [60, 61]. MLCK-mediated phosphorylation enables myosin–actin cross-bridge

cycling [62], driving GI smooth muscle contraction [63, 64] (Fig. 1). Meanwhile,

SOCE, mediated by stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1) and Orai calcium

release-activated calcium modulator 1 (Orai1) following depletion of

intracellular calcium stores, helps maintain the cytosolic calcium levels,

supporting sustained contraction and regulating transcriptional programs. In

murine injury models, in vivo knockdown of Orai1 prevented the

upregulation of STIM1 and CamKII

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration of the calcium ion-mediated smooth muscle contraction–relaxation cycle mechanism. ICC, Interstitial Cells of Cajal, specialized cells that generate slow wave potentials and regulate muscle contraction; M3 Receptor, Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor subtype 3, involved in smooth muscle contraction; Gq Protein, A G protein that activates phospholipase C (PLC), producing IP3 and DAG as second messengers; IP3, Inositol 1,4,5-Trisphosphate, a second messenger that releases calcium from intracellular stores; DAG, Diacylglycerol, a second messenger that activates protein kinase C (PKC); ANO1, Anoctamin 1, a calcium-activated chloride channel involved in regulating smooth muscle contraction; VGCC, Voltage-Gated Calcium Channels, responsible for calcium influx during depolarization; CaM, Calmodulin, a calcium-binding protein that activates other proteins, including myosin light chain kinase (MLCK), to mediate muscle contraction; SERCA, Sarcoplasmic/Endoplasmic Reticulum Calcium ATPase, a pump that transports calcium into the sarcoplasmic or endoplasmic reticulum; RYR, Ryanodine Receptor, responsible for releasing calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum during muscle contraction; MLCK, Myosin Light Chain Kinase, an enzyme that phosphorylates myosin light chains to enable muscle contraction; MLC, Myosin Light Chain, a component of myosin that interacts with actin to initiate muscle contraction; NGX, Na+/Glucose Symporter, a protein that co-transports sodium and glucose; ATP, Adenosine Triphosphate, the energy currency of the cell, used in muscle contraction and other cellular processes.

The figure demonstrates the critical role of calcium ions (Ca2+) in the contraction process of smooth muscle cells. Calcium signaling initiates both the influx of extracellular calcium and the release of intracellular calcium stores, resulting in promoted IP3-mediated calcium release through type-3 IP3Rs. The increase in Ca2+ levels facilitates its binding to calmodulin, which in turn induces MLCK phosphorylation at Ser-1760, ultimately leading to smooth muscle contraction.

Interstitial cells of Cajal (ICCs) act as natural pacemakers in the gut, producing rhythmic electrical signals (slow waves) that synchronize the muscle contractions for digestion [66]. ICCs integrate the neural inputs from the enteric neurons and vagus nerve, responding to excitatory (e.g., acetylcholine, ACh) and inhibitory (e.g., nitric oxide) neurotransmitters [67]. This calcium fluctuation subsequently activates the chloride (Cl–) channel ANO1 (TMEM16A), leading to membrane depolarization and slow wave initiation [68, 69]. However, the emerging ANO1-mediated pathways have been validated in isolated experiments and animal models, but they lack sufficient evidence in human systems. Although these mechanisms may be relevant, they should be interpreted with caution and warrant further investigation to clarify their role in pathogenesis. Alternatively, it enhances the SERCA-mediated calcium reuptake into the SR and PMCA-dependent calcium extrusion, thereby terminating calcium oscillations [68, 69].

Current studies have revealed that calcium signaling is locally concentrated within the microdomains formed at caveolae—specialized plasma membrane invaginations serving as platforms for signaling proteins and receptors—and at ER–PM junctions [66, 70]. Within these domains, the calcium signals integrate with second messengers, including IP3 and cADPR. These finely tuned signals regulate the calcium-sensitive kinases, including PKC and Rho-associated kinase, which collectively orchestrate the phasic and tonic contractions [71].

Aberrant calcium signaling has been implicated in various GI motility disorders, including irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), diabetic gastroparesis, and intestinal pseudo-obstruction. In IBS rat models, the abnormal expression of IP3R, particularly type III, and upregulation of CaV3.2 T-type calcium channels are closely associated with smooth muscle hypercontractility and visceral hypersensitivity [57, 72]. In diabetic mouse models, CaV1.2 downregulation correlates with impaired vascular smooth muscle responsiveness [73]. Moreover, STIM1 and Orai1 overexpressions enhance SOCE, accelerating small intestinal smooth muscle contraction and increasing the intestinal transit rate [74].

Proinflammatory cytokines, including TNF-

A range of pharmacological agents targeting calcium signaling have shown promising effects in preclinical studies. For instance, SOCE inhibitors, including BTP2 and myosin light chain kinase blockers, reportedely alleviate excessive colonic contractions in IBS models. L-type calcium channel blockers, such as verapamil, have demonstrated efficacy in treating esophageal motility disorders; however, their limited bioavailability in the distal GI tract restricts the therapeutic efficacy in that region.

CaSRs, expressed in both smooth muscle cells and ICCs, regulate muscle tone via

the Gq/11–PLC

Despite these advances, numerous unresolved challenges remain. Most current evidence stems from animal models, whose ion channel expression profiles often differ from those of humans, thereby limiting translational validity. Moreover, some studies were conducted in vascular or skeletal muscle rather than in GI tissues. Future research should incorporate human-derived organoid systems and advanced imaging technologies to uncover ion and signaling regulation under pathological conditions. This will be crucial for bridging the gap between mechanistic insights and clinical applications.

Gastric acid, secreted by parietal cells, serves multiple physiological roles, including protein digestion, microbial sterilization, gut microbiota regulation, iron/calcium/vitamin B12 absorption facilitation, and digestive enzyme activation [77]. Acid secretion is mediated by the proton pump (H+/K+-ATPase), whose activity is regulated by scaffolding proteins, including A-kinase anchoring proteins and Na+/H+ exchanger regulatory factor family members that coordinate its membrane trafficking and phosphorylation state [78, 79]. This pump extrudes H+ into the gastric lumen in exchange for K+, with concurrent activation of apical Cl– channels and basolateral HCO3–/Cl– exchangers to maintain intracellular pH homeostasis during proton extrusion. Luminal H+ combines with Cl– to form HCl, which is the primary constituent of gastric acid [80].

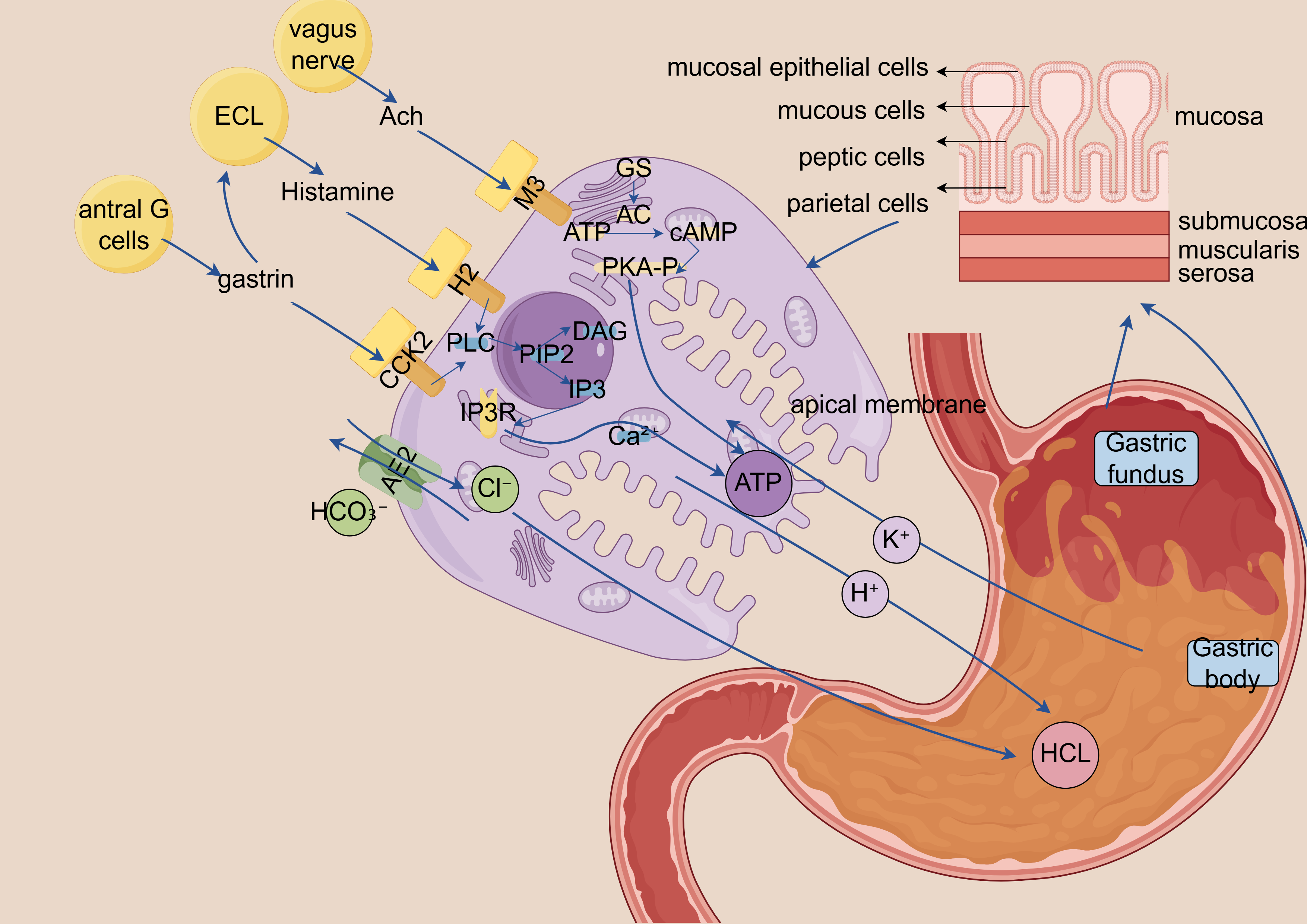

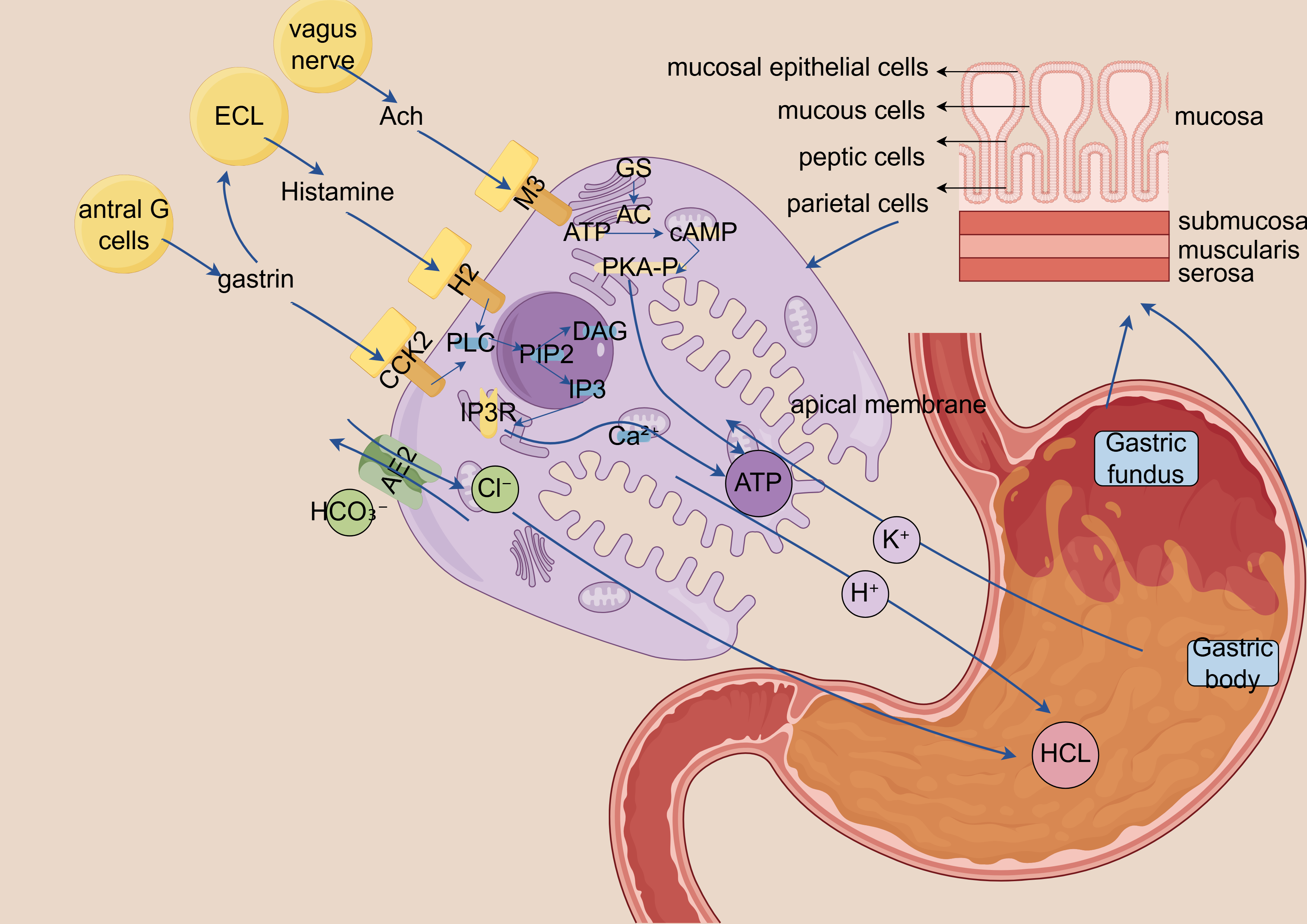

Gastric acid secretion primarily depends on H+/K+-ATPase activation in parietal cells, a process coordinately regulated by the following three major stimulatory factors: gastrin, acetylcholine, and histamine [77]. Calcium signaling primarily regulates the following two upstream pathways, which both trigger the Gq–PLC–IP3 signaling cascade: acetylcholine stimulates the Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor 3 and gastrin activates the Cholecystokinin type 2 receptor. This leads to the release of Ca2+ from the ER, resulting in increased cytosolic calcium levels that subsequently activates the H+/K+-ATPase proton pump [81, 82, 83]. Additionally, histamine activates the H2 receptors on parietal cells, initiating the cAMP–protein kinase A (PKA) signaling pathway, which synergistically regulates the magnitude and duration of gastric acid secretion. Upon ER calcium depletion, the STIM1/Orai1 complex mediates SOCE, serving as a critical mechanism for sustaining calcium signaling during prolonged stimulation (Fig. 2) [81, 82].

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Schematic diagram of calcium ion-dependent gastric acid

secretion signaling mechanism. ECL, Enterochromaffin-like cells, gastric endocrine cells that release histamine

in response to gastrin and acetylcholine to stimulate acid secretion; Ach,

Acetylcholine, neurotransmitter released by vagus nerve endings that activates M3

receptors on parietal and ECL cells; M3, M3 muscarinic receptor, Gq

protein-coupled receptor on parietal/ECL cells that, when activated by

acetylcholine, stimulates PLC signaling; H2, Histamine H2 receptor, Gs

protein-coupled receptor on parietal cells that, when activated by histamine,

stimulates cAMP production and acid secretion; CCK2, Cholecystokinin B receptor

(gastrin receptor), Gq protein-coupled receptor on ECL cells that triggers

histamine release when activated by gastrin; GS, Stimulatory G protein

(G

Aberrant regulation of calcium signaling pathways can lead to the dysregulation of gastric acid secretion [83].

In hyperacidic conditions associated with diseases, including PUD and GERD, the gastrin-calcium signaling axis is hyperactivated, resulting in increased calcium sensitivity of the parietal cells [84]. Helicobacter pylori infection induces epidermal growth factor (EGF) expression, which, via the MAPK pathway involving the EGF receptor, C-Raf, Mek1, and Erk2, upregulates gastrin expressi [85, 86].

Conversely, in atrophic gastritis or following long-term PPI use, calcium signaling is attenuated alongside impaired gastrin negative feedback, resulting in sustained hypochlorhydria that adversely affects protein digestion and mineral absorption. Notably, chronic acid suppression (e.g., via PPIs) may impair calcium bioavailability by reducing the solubilization of insoluble calcium salts, potentially contributing to long-term hypocalcemia and altered bone metabolism [87]. Long-term use of PPIs can induce a pathologic mucosal state characterized by disruption of the compartmentalization of mucosal component cells [88].

Calcium signaling pathways offer multi-layered pharmacological targets for gastric acid regulation. Compared with conventional H2 receptor antagonists and PPIs, modulators targeting calcium signaling—including CaSR agonists or antagonists—provide more refined regulatory potential. For instance, CaSR agonists have demonstrated therapeutic value in suppressing gastrin secretion induced by hypercalcemia. Additionally, calcium signaling modulators may play a role in regulating gastric acid secretion in H. pylori-associated gastric mucosal abnormalities.

From a diagnostic perspective, dynamic monitoring of calcium signaling to assess parietal cell functional activity and acid pump translocation efficiency could emerge as a novel, non-invasive approach for evaluating the gastric acid secretory status. Furthermore, polymorphisms in calcium signaling-related genes (e.g., STIM, Orai, CaMK) may contribute to inter-individual variability in acid secretion, highlighting their potential significance in the context of precision medicine.

This schematic illustrates the central regulatory role of calcium ions (Ca2+) in gastric acid secretion. (1) Histamine enhances calcium sensitivity via the cAMP-PKA signaling pathway. (2) Acetylcholine induces endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release through IP3-mediated signaling. (3) Gastrin directly promotes extracellular Ca2+ influx. Acting as a pivotal second messenger, Ca2+ integrates signals from multiple pathways to ultimately activate the proton pump (H+/K+-ATPase) and drive acid secretion.

Dysregulated calcium signaling can lead to aberrant gastric acid secretion. Excessive acid production may contribute to GERD and PUD, whereas insufficient acid secretion can result in dyspepsia and impaired nutrient absorption.

The intestinal barrier effectively prevents bacterial toxins and harmful substances from entering the systemic circulation. Calcium plays a pivotal role in regulating both the epithelial barrier function and immune homeostasis.

Barrier integrity primarily depends on TJs between intestinal epithelial cells

(IECs). TJs comprise the following four principal transmembrane protein families,

which collectively govern the solute flux through size/charge-selective

paracellular channels: occludin (with extracellular loop domains), claudin

multigene family (24 members in humans), JAMs (immunoglobulin superfamily

members), and tricellulin (concentrated at tricellular contacts) [89]. Claudins

constitute a human multigene family comprising at least 27 members, playing a

central role in regulating paracellular permeability by controlling the selective

passage of charged ions and molecules based on size. Recent studies have shown

that the Claudin-3 expression is lost in the intestines of IBD patients and in

colitis mouse models. This loss leads to increased intestinal permeability,

impaired barrier function, and exacerbated mucosal inflammation. When subjected

to colitis, mice transplanted with Claudin-3 knockout cells exhibited more severe

colitis (p

In intestinal immunity, calcium signaling activates immune regulators, including the nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT), modulating immune cell proliferation and differentiation to maintain immune homeostasis [94]. Calcium signaling also enhances epithelial cell migration by regulating the cytoskeletal dynamics and adhesion molecules, thereby accelerating wound healing [95]. Additionally, calcium-regulated epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) alters epithelial cell polarity and adhesion, promoting cell migration and barrier remodeling. Although this transformation is beneficial during mucosal repair, excessive activation may exacerbate chronic inflammation, intestinal fibrosis, or even malignant transformation [96].

The CaSR functions as a key regulator of calcium homeostasis. It is expressed on both the apical and basolateral membranes of enterocytes in the small intestinal villi, as well as on the surface and crypt epithelial cells of the colon in both rodents and humans [97]. In mice with intestinal epithelium-specific deletion of CaSR, intestinal barrier integrity is compromised, accompanied by an altered gut microbiota composition and disrupted local and systemic immune responses [98].

Calcium signaling regulates IEC proliferation through calcium/CaM-dependent

protein kinase (CaMK) and PKC activations. Under pathological conditions, CaMKII

hyperactivation promotes proinflammatory factor release (e.g.,

NF-

In IBD, persistent chronic inflammation can lead to intestinal fibrosis by

initiating a prolonged wound healing response and excessive extracellular matrix

(ECM) deposition. This fibrotic remodeling may result in complications, including

intestinal strictures and obstructions, ultimately leading to impaired GI

function [101]. Studies using murine models have demonstrated that EMT contributes

to intestinal fibrosis by serving as a novel source of fibroblasts [101]. Clinical

investigations have further revealed an increased EMT activity in the intestinal

tissues of Crohn’s disease (CD) patients with a penetrating behavior, which is

associated with enhanced WNT2b/FZD4 signaling [102]. During EMT, epithelial

markers, including E-cadherin and occluding, are progressively downregulated,

whereas mesenchymal markers, including

SOCE components, particularly STIM1, play a pivotal role in regulating the IEC barrier function during inflammation. STIM1 expression is elevated in the IECs and lamina propria mononuclear cells from the inflamed tissues of patients with IBD. Consequently, pharmacological blockade of SOCE may exert both anti-inflammatory and anti-tumor effects [104]. Moreover, CaSR activation has been demonstrated to preserve the TJ integrity in the intestinal epithelium of rats with endotoxemia, while also enhancing the levels of SCFAs, which support barrier function and immune regulation [105].

Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), a secondary bile acid derived from host–gut

microbiota interactions, has been identified as a potential modulator of

inflammation-induced EMT. UDCA exerts its anti-inflammatory effects by inducing

TGR5-dependent expression of suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 in murine

macrophages, thereby inhibiting the EMT processes driven by inflammation [106].

These findings highlight UDCA as a potential therapeutic target for

inflammation-associated CRC and underscore the need for further investigation

into the role of the gut microbiota in EMT modulation and related therapeutic

strategies. In vitro studies using IEC models have demonstrated that

agents such as methylprednisolone, budesonide, and adalimumab exhibit

anti-fibrotic effects. These drugs markedly inhibit TGF-

However, the current calcium-related therapeutic strategies still face considerable challenges in clinical translation. On one hand, calcium signaling exhibits bidirectional regulatory properties (while transient physiological elevation promotes tissue repair, sustained pathological elevation may exacerbate inflammation and facilitate tumor progression). On the other hand, the heterogeneous distribution and function of various calcium channels across different cell types complicate the development of precise interventions. Integrative multi-omics approaches combined with profiling of immune-related molecular signatures may help uncover candidate mechanisms underlying IBD progression and facilitate the identification of novel therapeutic targets [108].

Recent studies suggest that calcium regulation within the GI system is not confined to local processes, but it is embedded within broader inter-organ communication networks, including the gut–liver, gut–bone, and gut–brain axes. Calcium-dependent signaling along these axes plays a pivotal role in regulating metabolic homeostasis, maintaining barrier function, and orchestrating systemic responses, offering considerable implications for disease mechanisms and therapeutic interventions.

Recently, the gut–liver axis has emerged as a critical hub for inter-organ calcium signaling, playing a key role in maintaining intestinal homeostasis, regulating hepatic metabolism, and mediating the pathogenesis of various digestive system diseases. Intestinal barrier dysfunction often leads to gut microbiota dysbiosis and bacterial product (e.g., endotoxins) translocation into the liver via the portal vein, where they activate the Kupffer cells and associated immune pathways. This process induces hepatic inflammation and oxidative stress, forming a fundamental mechanism underlying metabolic diseases, such as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) [109, 110, 111]. In patients with portal hypertension secondary to chronic liver disease, impaired intestinal barrier function and microbial translocation exacerbate hepatic fibrosis and further elevate portal pressure [112]. This may represent a promising therapeutic target for liver diseases through the modulation of the gut–liver axis.

Moreover, calcium signaling plays a central role in this process, not only by

regulating hepatic lipid and glucose metabolism, but also by influencing bile

secretion and cellular stress responses. Dysregulation of calcium signaling is

closely associated with NAFLD, insulin resistance, and hepatic fibrosis [113].

Notably, the pigment epithelium-derived factor PEDF, secreted by the liver, can

regulate the proliferation and differentiation of intestinal stem cells and

maintain epithelial homeostasis by inhibiting the Wnt/

As the primary site of calcium absorption, the intestine plays a crucial role in maintaining bone homeostasis. Particularly, SCFAs produced by the gut microbiota markedly influence both bone formation and resorption. In murine models, acetate and propionate promote osteogenic and adipogenic differentiations of mesenchymal stem cells via the SCFA receptors Gpr41 and Gpr43, thereby modulating bone mass [117, 118]. Additionally, SCFAs can indirectly enhance osteogenesis by promoting the generation of regulatory T cells (Tregs) from naïve CD4+ T cells, contributing to bone-immune homeostasis. The expansion of Tregs upregulates the Wnt10b expression, suppresses osteoclastogenesis, and promotes bone formation, ultimately improving bone mineral density [119, 120].

In ovariectomized mouse models, combined supplementation with calcium and probiotics considerably reduced bone loss [121]. A recent meta-analysis also reported that probiotic supplementation may benefit bone health in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis, although the optimal bacterial strains remain to be identified [122]. Furthermore, modulating the SCFA levels can alleviate inflammation in ankylosing spondylitis mouse models [123]. This intervention also appears to reverse bone loss, highlighting the potential translational relevance of these findings in the management of osteoporosis.

Recently, many studies have closely linked the gut–brain axis with inflammation susceptibility in IBD and Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Adrenal axis dysregulation, yet the bidirectional signaling of the brain–gut axis remains unclear [124]. In rat models, calcium channel blockers, including verapamil, demonstrate some efficacies in alleviating the symptoms of ulcerative colitis (UC) and reducing mucosal damage [125]. Concurrently, these drugs considerably improve patients’ depression and anxiety status, although the incidence of adverse effects is relatively high. Thus, further research on signaling mechanisms is warranted, as calcium may be a missing component in neurotransmission.

Although the mechanistic framework has been gradually established, there is still a lack of well-defined clinical trials targeting inter-organ calcium signaling. Most current intervention strategies remain focused on calcium intake or absorption efficiency, without systematically evaluating their effects on multi-organ signaling networks.

Intestinal microbial communities exert essential functions in nutrient processing and maintenance of mucosal immunological defenses. Calcium exerts multifaceted effects on the gut microbiota by modulating the intestinal environment, microbial metabolism, and host immune interactions.

Calcium regulates the intestinal environment primarily by modulating the luminal pH. Gut microbiota-derived metabolites, including SCFAs, bile acids, tryptophan metabolites, LPS, and methane, shape the luminal environment [126]. Calcium binds to luminal acids (e.g., SCFAs and bile acids), forming insoluble calcium salts that reduce the free acid concentrations and elevate the pH levels. This may inhibit the acidophilic bacteria (e.g., certain Lactobacillus spp.) while promoting the proliferation of neutral or weakly alkaline-adapted species (e.g., Bacteroides). Moreover, by binding to free bile acids, it can alleviate mucosal irritation and inflammation [127], thereby protecting the intestinal barrier and inhibiting bile acid-dependent bacteria, including certain Clostridium species [128]. It is noteworthy that these buffering effects are also influenced by dietary components and baseline microbiota composition of the host, which further modulate the microbial feedback regulation in response to the pH [129, 130].

Both animal and human studies have shown that calcium supplementation can markedly alter the gut microbiota composition, although interspecies biological differences persist. Moreover, the effects on microbial communities and their functions may vary depending on the form, concentration, and duration of calcium intake, as well as dietary context and interactions with other trace elements. The relevant studies are summarized in Table 1 (Ref. [131, 132, 133, 134, 135]).

| Study subjects | Type and dose of calcium | Duration | Microbiota changes | Intestinal effects | Reference | |

| Animal studies | Male C57BL/6J mice (n = 8) | 12 g/kg/day calcium carbonate | 6 weeks | ↑ Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, Bacteroides/Prevotella, Bifidobacterium spp.; ↓ Clostridium spp. | Reduced plasma endotoxin levels, enhanced barrier function, improved metabolic disorders, reduced inflammation | [131] |

| Male Wistar rats (n = 8) | 13.60 g/kg/day calcium hydrogen phosphate (CaHPO4) | 2 weeks | ↑ Firmicutes (e.g., Romboutsia, Roseburia, Ruminoclostridium, Ruminococcus) | Increased SCFA production | [132] | |

| Male C57BL/6 mice (n = 8) | 0.4% or 1.2% calcium carbonate and calcium citrate | 50 days | 1.2% of calcium carbonate and calcium citrate: ↑ Akkermansia abundance | 1.2% citrate reduced TNF- |

[133] | |

| Human clinical studies | Healthy adults (30 males, 32 females) | 1000 mg/day calcium and phosphorus | 8 weeks | ↑ Clostridium XVIII in males; no significant change in females | Affected SCFA production | [134] |

| Healthy adults (n = 12) | 1: 2 g/day calcium; 2: 15 g/day inulin; 3: 2 g calcium + 15 g inulin | 4 weeks | 1: ↓ Proteobacteria; 2: ↓ Verrucomicrobia; 3: ↑ both phyla | Inulin enhanced calcium absorption; limited metabolic impact of calcium alone | [135] | |

↑ indicates an increase in microbial abundance; ↓ indicates a decrease in microbial abundance.

Beyond its role in regulating the intestinal epithelium, calcium also participates in mucosal immune modulation by affecting T-cell differentiation and effector functions. T cells are essential for detecting and eliminating infected cells and for modulating the overall immune response. Calcium plays a central role in T-cell activation. Upon T-cell receptor engagement, calcium is released from the ER. The depletion of ER calcium stores is sensed by STIM1, which subsequently activates the Orai1 channel to form a calcium release-activated calcium (CRAC) channel, allowing extracellular calcium influx into the cytoplasm. The resulting increase in cytosolic calcium level activates NFAT, a transcription factor that governs extensive gene networks essential for T-cell activation and function [136, 137].

During this process, calcium flux regulates the key metabolic pathways, including glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation, and in turn, is modulated by metabolic intermediates [138]. For example, vitamin D exhibits a dose-dependent effect on calcium flux and NFAT activation. In mice, high doses of vitamin D enhance calcium influx and promote susceptibility to autoimmunity, whereas moderate doses induce Treg development [139]. Contrarily, retinoic acid, a metabolite derived from vitamin A, reduces the NFATc1 protein levels in both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, leading to impaired T-cell activation [140].

ROS are a group of highly reactive and unstable free radicals and non-radical oxygen-containing compounds that play essential roles in antimicrobial defense and immune regulation [136]. ROS are also essential for NFAT signaling pathway activation in T cells [141]. Calcium regulates ROS production by promoting mitochondrial metabolism and oxidative stress responses, thereby contributing to the induction of antimicrobial peptide expression and repair of epithelial barriers [142]. However, calcium signaling must also activate the antioxidant pathways, such as the Nrf2 pathway, to prevent excessive ROS accumulation and subsequent intestinal tissue damage [143]. Accordingly, mitochondrial-targeted antioxidants, such as MitoQ, can alleviate mitochondrial DNA damage by activating the Nrf2/ARE signaling pathway, thereby preventing excessive ROS accumulation and mitigating intestinal barrier injury caused by ischemia–reperfusion [144]. The calcium-regulated redox homeostasis mechanism is pivotal for maintaining a state of low-grade inflammation and immune tolerance in the gut, highlighting calcium’s dual role in host–microbiota signaling regulation [145].

PUD is a common GI disorder characterized by mucosal defects in the stomach or duodenum, often presenting with recurrent, cyclic epigastric pain [146].The primary etiologies include H. pylori infection (accounting for 57%–70% of cases) and excessive nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use (20%–30%) [147]. Although considerable advances have been made in H. pylori eradication and acid-suppressive therapies, recurrence and complications remain frequent, prompting increased interest in host-related factors—particularly the role of calcium in mucosal susceptibility and repair mechanisms.

Calcium signaling plays a bidirectional role in peptic ulcer development and healing. On one hand, NSAID-associated PUD flare-ups or recurrences often occur in cases with elevated serum calcium levels (3 mmol/L), which can disrupt the gastric microcirculation, activate the acidic digestive factors, and impair GI motility—collectively promoting ulcer formation and chronicity [148, 149]. On the other hand, calcium is essential for maintaining epithelial integrity, mediating cell adhesion, and promoting mucosal regeneration, particularly in cases of H. pylori infections [150].

H. pylori infection is a primary pathogenic factor in PUD development.

It disrupts calcium signaling through multiple virulence mechanisms. The VacA

toxin induces mitochondrial Ca2+ efflux and eosinophilic Ca2+ influx,

triggering the activation of the NF-

Nagano et al. [155] have demonstrated that indomethacin treatment in gastric epithelial RGM1 cells leads to a decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential and an increase in ROS level, ultimately inducing apoptosis. The underlying mechanism may involve NSAID-induced lipid peroxidation mediated by mitochondrial superoxide generation in gastric epithelial cells [156]. Rebamipide, a gastroprotective agent, exerts anti-ulcer effects by attenuating indomethacin-induced mitochondrial damage, lipid peroxidation, and apoptosis in gastric epithelial cells [157].

In patients with bulbar ulcer (BU) and arterial hypertension, disturbances in calcium homeostasis are often reflected by altered serum calcium levels [149]. For those with recurrent BU combined with hypertension, the adjunctive use of sustained-release calcium channel blockers [e.g., nifedipine (BMCT)] markedly enhances mucosal blood flow, thereby accelerating ulcer healing and improving the healing rates [158].

Given the bidirectional effects of calcium in GI physiology, therapeutic strategies should be tailored to individual patient profiles. In NSAID users, careful monitoring of serum calcium levels and judicious use of calcium channel blockers may mitigate adverse outcomes. For patients requiring calcium supplementation, calcium citrate—owing to its acid-independent absorption—should be prioritized. The recommended intake should not exceed 500 mg per day, with serum calcium levels maintained within the physiologic range of 2.25–2.50 mmol/L to avoid the development of hypercalcemia-associated complications.

In the management of H. pylori-associated ulcers, PPIs, including omeprazole and lansoprazole, remain the cornerstones of standard eradication therapy [159]. However, PPI use has occasionally been linked to hypocalcemia, potentially resulting in neuromuscular symptoms such as muscle cramps or tetany [160]. Hence, long-term PPI users should undergo regular serum calcium surveillance. Although calcium supplementation may contribute to mucosal protection, current evidence remains inconclusive, and more high-quality clinical trials are needed.

Notably, calcium-based antacids can interfere with the pharmacokinetics of PPIs and certain antibiotics, warranting cautious co-administration. Given that PTH regulates systemic calcium balance, patients with hypoparathyroidism or post-parathyroidectomy who rely on supplementation should also preferentially receive calcium citrate during PPI-based H. pylori therapy to ensure effective and safe calcium absorption [161].

Future research should focus on delineating the optimal clinical strategies regarding the type, dosage, and timing of calcium supplementation in ulcer management, as well as systematically evaluating the interactions between calcium-based antacids, PPIs, and antimicrobial agents.

Although previous mechanistic studies suggest that calcium may play a protective role in ulcer defense, its clinical effects in vivo remain inconclusive. For instance, the mucosal protective effects observed in vitro may not be applicable under inflammatory or ulcerative conditions. Moreover, whether calcium-based antacids interfere with H. pylori eradication remains unclear, with existing evidence being limited and conflicting. Most current studies rely on animal or cellular models, and large-scale human data are still lacking.

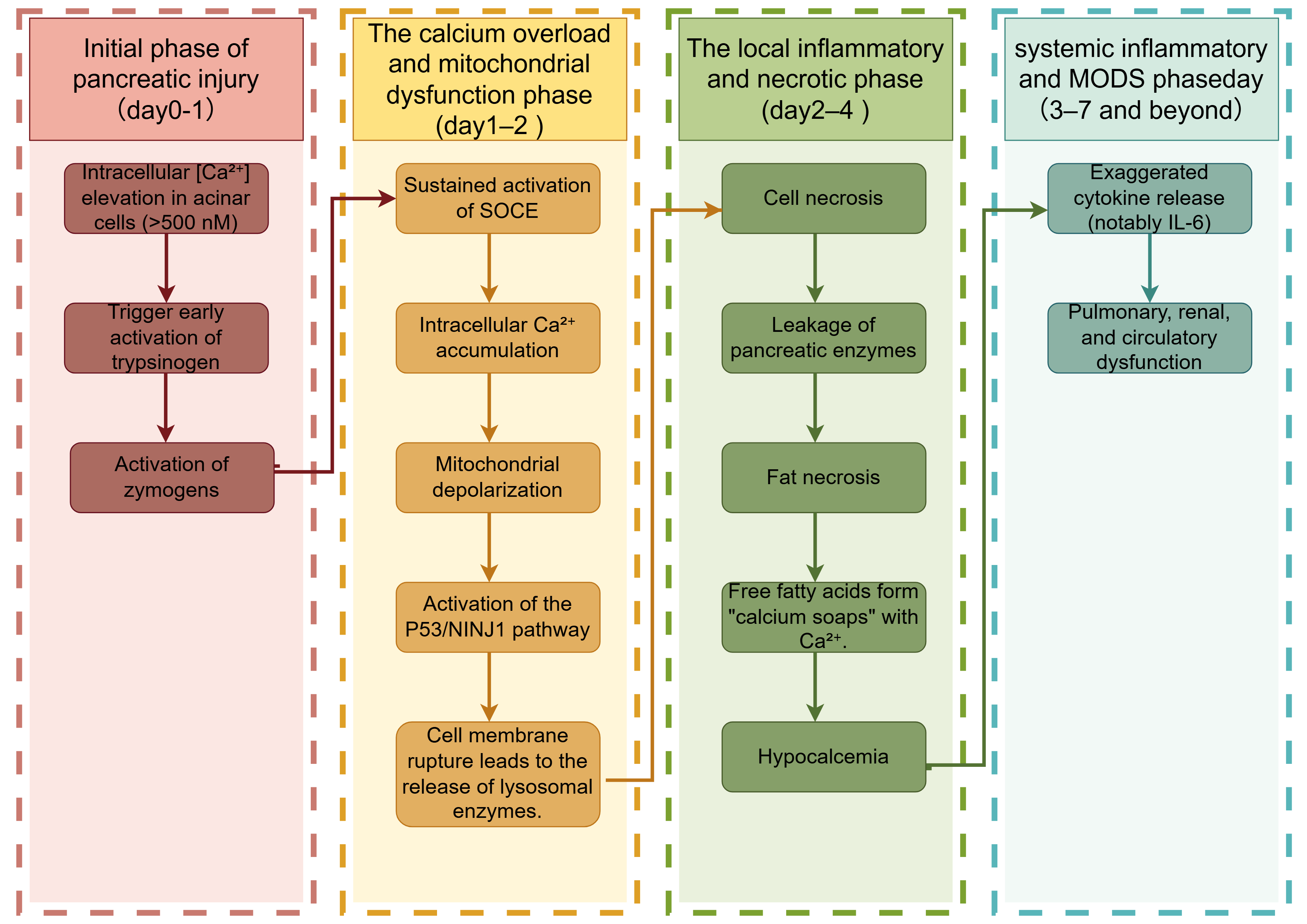

AP is a sudden-onset inflammatory disorder characterized by the premature

activation of digestive enzymes—most notably trypsinogen—within the pancreas,

leading to autodigestion of the pancreatic parenchyma. Clinically, AP presents

with severe abdominal pain and marked serum amylase and lipase level elevations.

In its severe form, the disease can progress rapidly to systemic inflammatory

response syndrome, cytokine storm (e.g., interleukin-6

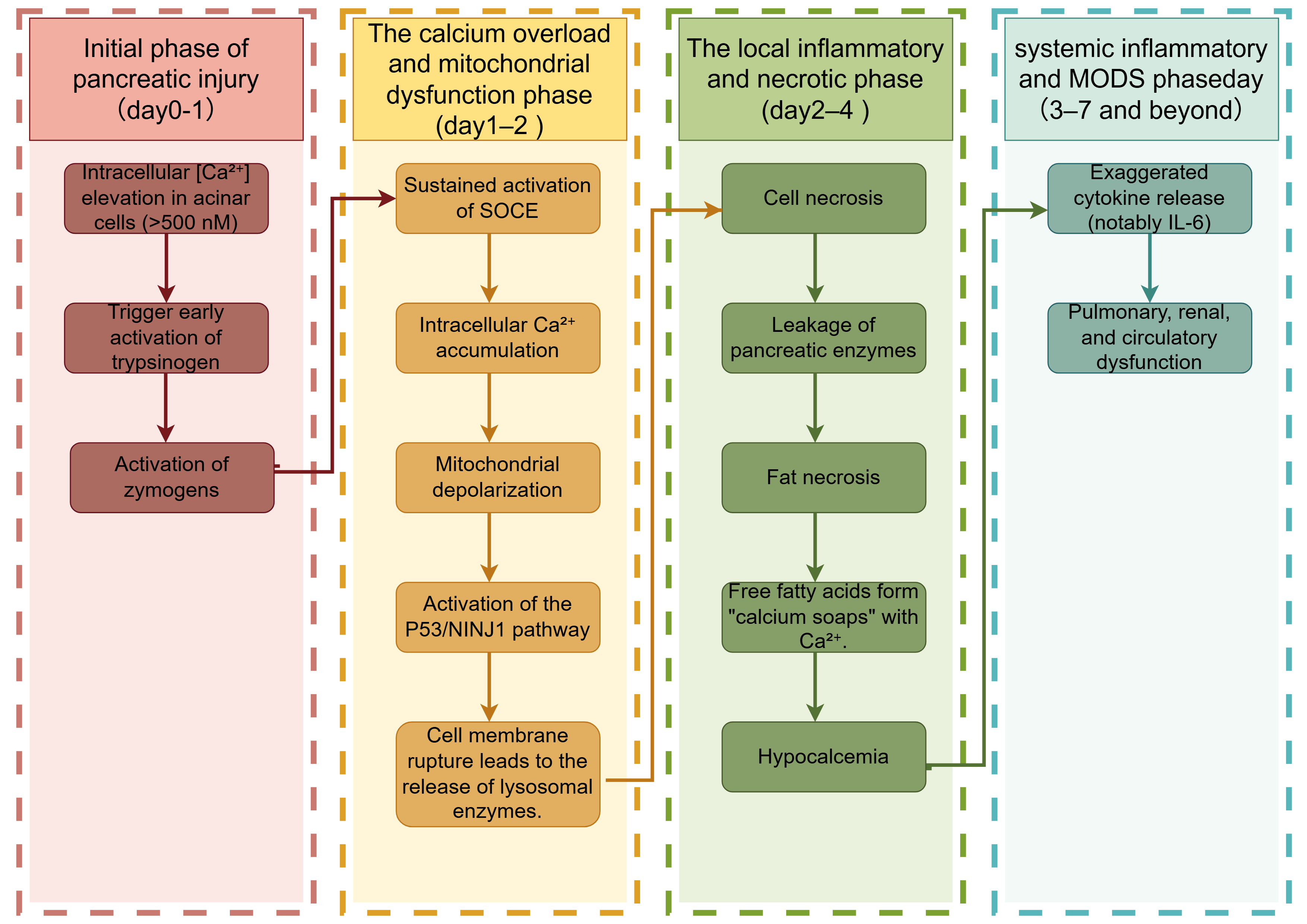

Hypocalcemia is a common electrolyte disturbance in AP. During pancreatic necrosis, lipase released into the surrounding tissues hydrolyzes fat into free fatty acids [164], which bind Ca2+ to form “calcium soaps”, reducing the serum calcium levels [165]. At the cellular level, AP inhibits PMCA, causing extracellular Ca2+ influx, serum hypocalcemia, and intracellular calcium overload. Elevated intracellular Ca2+ levels precipitate mitochondrial dysfunction and activate the p53/NINJ1 signaling cascade, ultimately leading to plasma membrane rupture in pancreatic acinar cells (Fig. 3) [166].

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Calcium signaling from early pancreatic injury to multi-organ

failure. SOCE, Store-Operated Calcium Entry, a calcium influx pathway activated by

depletion of endoplasmic reticulum calcium stores, mediated by STIM-Orai

complexes; P53, Tumor Protein P53, a stress-responsive transcription factor that

regulates DNA repair, cell cycle arrest, and apoptosis; NINJ1, Nerve

Injury-Induced Protein 1, a transmembrane protein mediating plasma membrane

rupture during lytic cell death (e.g., pyroptosis, necrosis); MODS, Multiple

Organ Dysfunction Syndrome, a life-threatening systemic condition involving

progressive failure of

Disruption of calcium homeostasis is a hallmark of AP and serves as a critical

predictor of disease severity. Hypocalcemia not only reflects systemic

inflammation but also correlates with peripancreatic fat necrosis. The combined

APACHE II + serum Ca2+ scoring system has been utilized for early risk

stratification. Notably, an APACHE II score of

Clinically, although serum calcium plays a critical role in AP pathogenesis,

calcium supplementation alone provides no therapeutic benefit [169]. Notably,

while hypocalcemia typically stimulates PTH secretion, AP patients often exhibit

blunted PTH responses [170]. Magnesium, which is essential for PTH production and

secretion, can restore the PTH function by correcting magnesium deficiency,

thereby improving hypocalcemia [45]. Additionally, the serum vitamin D level

should be assessed. In AP patients, vitamin D levels of

In the clinical management of AP complicated by hypocalcemia, parenteral calcium supplementation alone has not demonstrated marked outcome improvement and may exacerbate cellular injury due to intracellular calcium overload. In cases of moderate severity, a combination of enteral and parenteral calcium supplementations may be cautiously considered [169]. Magnesium repletion, by restoring PTH responsiveness, offers a potential indirect strategy for correcting hypocalcemia [45]. Additionally, vitamin D supplementation may enhance the intestinal calcium absorption and modulate the inflammatory responses, representing a more effective and physiologically aligned approach to correcting hypocalcemia and supporting recovery [171].

Recent studies have highlighted SOCE, a key calcium signaling mechanism triggered by ER calcium depletion [172]. SOCE, mediated by Orai channels and STIMs. STIM1 is a single-pass transmembrane protein localized to the ER membrane, containing a luminal EF-hand domain that senses the intraluminal calcium levels. Upon ER calcium store depletion, STIM1 undergoes conformational changes, oligomerizes, and translocates to the ER–plasma membrane (PM) junctions. At these contact sites, it directly interacts with Orai1, a plasma membrane–localized CRAC channel, to initiate SOCE [173]. At the ER–plasma membrane junctions, STIM1 directly interacts with and activates Orai1, forming a functional SOCE complex that mediates a sustained calcium influx into the cytosol.

In recurrent AP and early-stage chronic pancreatitis (CP), aberrant overactivation of SOCE drives sustained intracellular calcium overload, thereby promoting acinar cell injury and accelerating the progression of pancreatic pathology [174]. Inhibiting the Orai channels may prevent progression to end-stage CP in patients with pancreatitis [175, 176]. However, Orai inhibitors remain confined to preclinical studies and early-phase clinical trials, with currently no approval for clinical use. The comprehensive evaluation of their efficacy and safety in large-scale patient cohorts is imperative before translation into standard therapeutic practice.

Future efforts should focus on biomarker optimization by integrating RDW as well as serum calcium, magnesium, and vitamin D levels to develop a robust and scientifically grounded risk stratification model, thereby enhancing the predictive accuracy for disease severity.

Targeting SOCE presents potential therapeutic risks, as prolonged inhibition of calcium influx may disrupt essential immune and secretory functions. Furthermore, clinical safety data in humans remain limited. Notably, the widely used prognostic scoring systems, such as APACHE II and BISAP, currently do not incorporate calcium-related parameters or SOCE-associated biomarkers, reflecting a critical gap in the integration of calcium signaling into clinical risk stratification.

CRC is among the leading causes of cancer-related mortality worldwide. Studies have indicated that adequate calcium intake reduces CRC risk, with more pronounced protective effects against distal colon cancer [177]. This suggests that calcium may play an important role in CRC prevention and treatment.

Calcium reduces the risk of CRC through multiple mechanisms. Dietary Ca2+

chelates deprotonated bile acids and ionizes fatty acids through electrostatic

interactions, forming insoluble soaps that reduce mucosal irritation and

carcinogenic risk [178]. Calcium may exert protective effects through synergistic

actions with vitamin D, activation of signaling pathways (e.g.,

Wnt/

The synergistic interaction between calcium and vitamin D warrants special attention. Vitamin D, as a key regulator of serum calcium homeostasis, not only enhances intestinal absorption of Ca2+ but also exerts anti-tumor effects by promoting cellular differentiation and apoptosis, thereby inhibiting cancer cell proliferation and metastatic potential [183]. CRC patients often exhibit reduced serum 1,25(OH)2D3 levels, which improve with vitamin D supplementation. A low calcium level is linked to CaSR and vitamin D metabolism [177].

The roles of calcium and vitamin D in CRC prevention and control are considerably influenced by individual genetic backgrounds. Particularly, polymorphisms in the VDR gene are considered key factors regulating individual responses to the calcium–vitamin D axis. Common VDR polymorphic sites, including TaqI, ApaI, FokI, BsmI, and Cdx-2, can affect VDR expression, mRNA stability, or its binding affinity to target genes, thereby modulating calcium absorption as well as cell proliferation and apoptosis pathways [184]. For example, a genetic analysis of CRC patients revealed the associations of serum calcium and vitamin D levels with specific genotypes; serum calcium levels are correlated with the heterozygous TaqI genotype (Tt) of the VDR gene, whereas vitamin D levels are linked to the homozygous ApaI genotype (aa) [177]. Another meta-analysis found that the BsmI variant was significantly associated with a reduced risk of CRC in Caucasians, whereas the Cdx-2 polymorphism was linked to a decreased CRC risk in African populations.

Regarding precision nutrition and personalized medicine, these polymorphisms can

be used to identify high-risk populations and guide calcium and vitamin D

intervention strategies. For example, individuals with a low VDR activity may

require higher vitamin D doses to maintain calcium homeostasis and exert

anti-tumor effects. Growing evidence suggests that, for individuals carrying

high-risk alleles, a daily intake of 800 International Units of vitamin D

combined with 1000–1200 mg of dietary calcium, along with regular monitoring of

serum 1,25(OH)2D3 levels with the aim of maintaining a level of

Genetic polymorphisms within the calcium signaling pathways also influence the tumor progression. Human colon cancer cell lines (e.g., CBS and Moser), derived from differentiated primary colon tumors, express functional CaSR. Ca2+ induces E-cadherin expression and suppresses the nuclear transcription factor TCF4, whereas 1,25(OH)2D3 induces cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors. Both act independently or synergistically to stimulate the CaSR promoter activity and protein expression in CBS cells, regulating epithelial differentiation [187]. A previous case–control study found that the CaSR gene polymorphism rs1801725 is associated with an increased risk of CRC development and poorer prognosis [188]. In a mouse model of Citrobacter rodentium infection, a high-calcium diet effectively reduced the TRPV6 mRNA expression and alleviated hyperplasia in the distal colon. However, it is important to note that excessive administration of active vitamin D metabolites may lead to aberrant overexpression of TRPV6, potentially promoting tumorigenesis and counteracting the protective effects of dietary calcium [188].

Recently, the strong link between calcium and CRC has spurred the development of novel diagnostic and therapeutic approaches.

A perovskite-based probe targeting survivin, a fluorescent biomarker, enables rapid early CRC diagnosis and tumor–normal tissue discrimination [189]. Modulating lysosomal calcium release regulates autophagy, inducing cancer cell death or enhancing therapeutic sensitivity [190]. Compounds, such as gossypol, inhibit CRC proliferation by disrupting the lysosomal function, blocking CaV3 channels, suppressing ER calcium uptake, and inducing G0/G1 and G2/M cell cycle arrests [191].

Endoscopic calcium electroporation uses high-voltage pulses to reversibly

permeabilize the cell membranes, enhancing intracellular calcium influx and

inducing tumor necrosis in advanced CRC [192]. Nanotechnology-mediated Ca2+

overload activates the mitochondrial apoptosis pathways, suppressing cancer

progression [193]. During radiotherapy, CRMP4 enhances the radiosensitivity in

colon cancer cells during radiotherapy by promoting calcium influx, which

activates the downstream signaling pathways leading to mitochondrial membrane

potential collapse [194]. The matrix Gla protein promotes CRC growth and

proliferation by increasing the intracellular calcium levels and activating the

NF-

Future research should focus on the integrative role of calcium within the gut ecosystem. Recent studies have increasingly highlighted the complex bidirectional regulatory mechanisms between calcium and gut microbial metabolites, such as SCFAs and bile acid derivatives [196]. These metabolites markedly influence epithelial cell proliferation, apoptosis, and differentiation, suggesting a substantial regulatory potential for calcium in CRC progression. Additionally, the roles of calcium in immune modulation and signaling within tumor-derived extracellular vesicles merit further investigation. Personalized intervention strategies incorporating genetic polymorphisms related to calcium and vitamin D metabolism may offer promising avenues for the precise prevention and treatment of CRC.

Despite substantial evidence supporting the anticancer effects of calcium, its protective efficacy across different stages, anatomical sites, and populations in CRC remains uncertain. Some studies have reported conflicting results, suggesting that under certain conditions, calcium signaling may exert pro-tumorigenic effects. Moreover, the complex interactions between calcium, vitamin D, genetic background, gut microbiota, and immune system pose considerable challenges to mechanistic elucidation. Currently, evidence supporting the effectiveness of calcium in advanced CRC therapy is limited, and excessive calcium intake may pose health risks. Therefore, more precise intervention strategies should be developed based on balanced nutrition and safe intake guidelines.

Dietary calcium often precipitates in the GI tract or forms insoluble complexes with oxalates, and its bioavailability is easily disrupted by other cations, necessitating calcium supplementation [197]. Recently, with the growing understanding of calcium’s physiological and pathological roles, the use of calcium supplements in the prevention and treatment of GI diseases has expanded considerably, demonstrating notable therapeutic benefits. Given the substantial differences among various types of calcium supplements in terms of chemical structure, solubility, bioavailability, and clinical indications, this section will sequentially introduce inorganic, organic, and natural calcium sources as well as chelated calcium preparations, and will analyze their distinctive applications in GI disease interventions (Table 2, Ref. [161, 198, 199, 200, 201, 202, 203, 204, 205, 206, 207, 208, 209, 210, 211, 212, 213, 214, 215, 216, 217, 218]).

| Type of calcium supplement | Absorption pathway | Bioavailability | Gastrointestinal tolerance | Clinical applications in gastrointestinal diseases | Recommended dosage |

| Inorganic Calcium (e.g., Calcium Carbonate, Calcium Phosphate) | Requires stomach acid for dissolution [161] | Low, dependent on stomach acid [198] | May cause constipation, bloating [199] | Suitable for individuals with normal stomach acid secretion; caution for kidney stone patients [198, 200] | 1000–2000 mg/day [201, 202, 203] |

| Organic Calcium (e.g., Calcium Citrate, Calcium Gluconate) | Absorbed without the need for stomach acid [161] | Higher, especially Calcium Citrate [198] | Good gastrointestinal tolerance, fewer side effects [204] | Suitable for individuals with low stomach acid secretion, post-gastric bypass patients [205] | 1000–1500 mg/day [206] |

| Natural Calcium Sources (e.g., Algae Calcium, Oyster Shell Calcium) | Better absorption, especially when heated [207] | Bioavailability 40%–60%, but varies by individual [208, 209] | Generally good tolerance, may contain heavy metals [210] | Suitable for individuals with high acidity, osteoporosis [211] | 1000–1500 mg/day [212] |

| Chelated Calcium (e.g., Amino Acid-Chelated Calcium, Peptide–Calcium Complex) | Does not rely on stomach acid, depends on transport proteins [213] | High bioavailability, 30%–60% [214] | Very good, suitable for individuals with gastrointestinal absorption disorders, but may cause allergic reactions [215] | Suitable for individuals with reduced stomach acid or fat malabsorption (e.g., IBD, short bowel syndrome) [216, 217] | 500–1000 mg/day [218] |

Inorganic calcium refers to calcium salts formed by the combination of Ca2+ with inorganic anions, such as carbonate (CO32-) and PO43-, including compounds such as CaCO3 and calcium PO43-. Owing to their low solubility and poor dissolution in water, these compounds require dissociation by gastric acid to release free Ca2+ for bioavailability in the small intestine. Therefore, co-administration with meals is recommended to enhance bioavailability [161]. CaCO3 is thus suitable for individuals with normal gastric acid secretion, but not for patients with conditions that impair gastric acid production, such as hypochlorhydria, atrophic gastritis, or those using PPIs [198].

Long-term or excessive use of inorganic calcium can cause side effects. In a randomized controlled trial (RCT), patients receiving CaCO3 were more likely to experience GI side effects, including constipation and bloating, as compared to those receiving placebo. These adverse effects may be related to reduced intestinal motility and decreased intestinal fluid secretion [199].

The impact of calcium supplementation on kidney stone formation remains controversial across studies. In one study involving 36,282 postmenopausal women aged 50–70 years with an average follow-up duration of 7 years, participants received either 1000 mg/day of CaCO3 or placebo. The results showed that the group receiving calcium and vitamin D had a 17% increased risk of developing kidney stones [200]. This may be attributed to excessive CaCO3 supplementation, which promotes the formation and growth of CaC2O4 crystals, thereby increasing the urinary calcium levels in individuals predisposed to kidney stones [204, 219]. Interestingly, a prospective cohort study involving 903,849 healthy women without a history of kidney stones found that high dietary calcium intake was associated with a reduced relative risk (RR) of kidney stone formation (RR = 0.65; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.50–0.83), whereas calcium supplementation was associated with an increased RR (RR = 1.20; 95% CI, 1.02–1.41) [220]. In another study involving 32 healthy male naval personnel, participants who took 3 g/day of CaCO3 with meals had a significantly lower risk of CaC2O4 kidney stone formation than those who took the same dose at bedtime [221]. These findings suggest that the impact of calcium supplementation on kidney stone risk may depend on the source of calcium and the timing of intake. Dietary calcium or CaCO3 taken with meals appears to pose a lower risk. However, the overall benefits and risks of CaCO3 supplementation in individuals with a history of kidney stones require further evaluation.

The phosphorus in calcium PO43- may exacerbate calcium-PO43- metabolism disorders in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) [222], with PO43- deposits damaging the renal tubules and accelerating CKD progression or acute kidney injury [223, 224]. It may also increase the cardiovascular risk by inducing vascular calcification, although the mechanisms require further study [225, 226].

Organic calcium refers to the salts formed by the combination of Ca2+ with organic acids, including citric, lactic, and gluconic acids, and includes compounds, such as calcium citrate, calcium gluconate, and calcium acetate. Compared to inorganic calcium, organic calcium exists as soluble salts and does not require gastric acid for bioavailability, allowing it to be taken with or without meals [161]. As a result, organic calcium is often used for calcium supplementation in patients with specific GI conditions. The following section outlines the clinical applications of the selected types of organic calcium in such diseases.

Insufficient gastric acid production is a major limiting factor for the bioavailability of inorganic calcium. In individuals with normal gastric acid secretion, the bioavailability rates of calcium citrate and CaCO3 are not significantly different. However, in patients with hypochlorhydric GI conditions or achlorhydria, the bioavailability of calcium citrate can be up to ten times greater than that of CaCO3 [198]. Therefore, calcium citrate is better suited for meeting the calcium needs of these populations.

RCTs have demonstrated that, compared to CaCO3, calcium citrate more effectively maintains stable serum calcium levels in patients undergoing gastric bypass surgery and reduces the incidence of secondary hyperparathyroidism [205, 227]. In contrast to the side effects associated with CaCO3, calcium citrate reduces urinary oxalate excretion, thereby lowering the risk of kidney stone formation, and is useful for both the prevention and treatment of nephrolithiasis [204, 228]. Moreover, calcium citrate exhibits superior GI tolerability, with fewer adverse effects, including bloating and constipation, which can enhance patient compliance [204].

The KDIGO guidelines [229] recommend careful selection of calcium-based supplements in CKD patients to avoid complications, such as vascular calcification and hypercalcemia, due to excessive calcium intake. Calcium acetate contains approximately 253 mg of elemental calcium per 1 g (approximately 25%), whereas CaCO3 provides approximately 400 mg of elemental calcium per 1 g (approximately 40%). Therefore, compared to CaCO3, calcium acetate may reduce the risk of hypercalcemia while effectively lowering the serum PO43- levels and providing calcium supplementation in CKD or ESRD patients [230]. The KDOQI guidelines [206] also support the use of calcium-based PO43- binders, including calcium acetate, as an effective initial therapy to control serum PO43-. However, they emphasize that total daily calcium intake—including both dietary and supplemental sources—should not exceed 1500 mg, and calcium supplementation strategies should be regularly adjusted based on the patient’s clinical status.

In murine models, calcium citrate reduces intestinal inflammation and alleviates metabolic disturbances induced by a high-fat diet. These effects are believed to be associated with the modulation of the gut microbiota composition and enhancement of SCFA production [133]. However, studies in this field remain limited in human clinical settings. Further research is warranted to elucidate the specific mechanisms by which calcium citrate may improve IBDs.

Calcium gluconate is typically administered intravenously and is the treatment of choice for acute cardiac arrhythmias caused by hyperkalemia [231]. The standard clinical protocol involves a slow intravenous injection of 10–30 mL of a 10% calcium gluconate solution (equivalent to 1–3 g of calcium gluconate) over a period of 2–5 minutes. The onset of action is usually observed within 1–3 minutes. If electrocardiographic abnormalities persist after the initial injection, repeat dosing may be considered.

The natural sources of calcium include algae, oyster shell, and others. Compared to inorganic calcium, calcium from natural sources exhibits higher bioavailability. A heated oyster shell–algae-derived calcium formulation may enhance intestinal calcium bioavailability due to its amino acid content [207]. Algae-derived calcium contains various natural minerals (e.g., magnesium, potassium, zinc, and iodine) and trace elements, providing additional nutritional benefits alongside calcium [232]. The algae-derived calcium’s alkaline nature may make it more suitable for individuals with hyperacidity.

In mouse models, the administration of Aquamin, a red algae-derived supplement rich in calcium, magnesium, and trace elements, reduces the risk of liver injury and lowers the liver tumor incidence [233]. Animal studies have shown that coral-derived calcium exhibits a significant inhibitory effect on pulmonary metastasis of colon cancer in mice [232]. Similarly, calcium derived from oyster shells has demonstrated inhibitory activity against oral squamous cell carcinoma in murine models [232]. However, these findings have not yet been validated in large-scale human clinical trials, and there is currently no evidence to support their GI applicability or long-term safety.

However, calcium from natural sources has drawbacks. Seaweed and oyster-based products may contain heavy metals [210], posing long-term health risks. Some brown algae (e.g., kelp) are high in iodine, and excessive intake may disrupt the thyroid function [234, 235].

Chelated calcium refers to complexes formed between Ca2+ and amino acids, peptides, or protein fragments, which considerably enhance solubility and transmembrane transport efficiency in the small intestine. These formulations are independent of gastric acid for bioavailability and reduce the likelihood of forming insoluble precipitates with compounds such as phytates and oxalates. This makes them particularly suitable for patients with impaired calcium bioavailability due to reduced gastric acid secretion (e.g., atrophic gastritis and PPI use) or fat malbioavailability syndromes [e.g., IBD and short bowel syndrome (SBS)]. The common forms of chelated calcium include amino acid chelates and peptide–calcium complexes.

Amino acid-chelated calcium is formed by the complexation of Ca2+ with individual amino acids such as glycine or glutamic acid. These compounds are absorbed in the upper small intestine via active transport mechanisms, including peptide transporters (e.g., PepT1) and calcium-binding proteins. Amino acids themselves enhance calcium digestion and bioavailability in the GI tract [213, 236]. Compared to inorganic calcium, chelated calcium formed by binding Ca2+ to amino acids exhibits greater stability, bioactivity, and bioavailability. As a result, it can achieve superior physiological effects at lower doses, with bioavailability efficiency of 30%–35%, which is significantly higher than that of inorganic calcium and indicates lesser dependence on gastric acid [214]. However, the higher production cost has limited its clinical research and application. Additionally, it may cause unwanted lipid interactions and color reactions [237].

Recently, peptide–calcium complexes have gained attention due to their superior stability and bioavailability under both acidic and alkaline conditions [238]. Peptide–calcium complexes are formed through multipoint chelation between Ca2+ and polypeptide chains. Peptide–calcium complexes enable calcium bioavailability through peptide-mediated channels, avoiding competition with other metal ions, such as magnesium and iron, and protecting calcium from precipitation by phytic and oxalic acids [239]. Compared to amino acids, peptides require less energy for bioavailability and exhibit higher bioavailability rates, ranging from 40% to 60%. Studies in normal male [235], calcium-deficient [236], and ovariectomized rats [239] have demonstrated that peptide–calcium chelates significantly improve calcium bioavailability and bone health, highlighting their potential as effective calcium supplements.

Peptides are derived from diverse edible sources, including tilapia [240], bovine bone [241], soybean [242], walnut [243], deer skin [244], and whey protein [245]. Additionally, by-products from seafood processing—such as octopus waste [246] and oyster shells [239]—have been explored as peptide sources, considerably reducing production costs and promoting sustainability. However, during protein or peptide processing, potentially allergenic compounds, such as biogenic amines, D-amino acids, and lysinoalaninem may be formed. Therefore, further research is needed to improve the safety profile by addressing its potential toxicity and allergenicity in animal models.

Building on this, recent advancements include casein phosphopeptide–calcium complexes with higher calcium retention in oxalate-rich environments [247]. Moreover, microencapsulated phosphorylated human-like collagen-calcium complexes exhibit favorable properties, including water solubility, non-toxicity, biocompatibility, and biodegradability [248]. It is important to note, however, that these findings have not yet been validated in human in vivo or clinical studies.

In pathological GI conditions, such as CP and SBS, fat malbioavailability commonly occurs. Unabsorbed fatty acids can bind with calcium to form insoluble soaps, thereby reducing the concentration of absorbable free calcium. Additionally, the impaired bioavailability of fat-soluble vitamin D further compromises the active calcium transport [215, 249]. In patients with IBD, celiac disease, or atrophic gastritis, mucosal injury and villous atrophy may lead to increased IEC permeability and reduced expression of calcium-binding proteins, thereby inhibiting active calcium transport. Given the bioavailability mechanisms and transport pathways of peptide–calcium chelates, these compounds hold considerable potential for calcium supplementation in such patient populations [216, 217].

Although the interplay between calcium and GI diseases has drawn growing scientific interest, current investigations exhibit notable shortcomings across several key domains. These limitations broadly fall into four primary categories described below.