1 Department of Thoracic Surgery, Tangdu Hospital, Air Force Medical University of People’s Liberation Army, 710032 Xi’an, Shaanxi, China

2 Department of Nursing, The Air Force Medical University of People’s Liberation Army, 710032 Xi’an, Shaanxi, China

3 Department of Clinical Immunology, Xijing Hospital, Air Force Medical University of People’s Liberation Army, 710032 Xi’an, Shaanxi, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) affects approximately one-third of the global population. Meanwhile, the development of MASLD is related to dysbiosis of the gut microbiota (GM). Our previous studies have shown that Vitamin K2 (VK2) has considerable potential to ameliorate mitochondrial dysfunction in mice fed a high-fat diet (HFD); however, the mechanism through which VK2 improves mitochondrial function and mitigates MASLD remains unclear.

This study aimed to elucidate the mechanism through which VK2 modulates MASLD.

A total of 80 C57BL/6J mice (4–5 weeks old) were fed a HFD for 16 weeks to establish the MASLD animal model. Additionally, VK2 was administered at a dose of 120 mg/kg/day for the last 8 weeks; 30 mice were fed a normal diet for the entire 24-week period. Mice were randomly divided into groups according to different experimental protocols. Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining, Oil Red O staining, and Cluster of Differentiation 11b (CD11b) immunofluorescence staining were used to detect liver histology and inflammatory cell infiltration in the mouse liver tissues. Moreover, 16S rRNA gene sequencing, antibiotic treatment, and fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) were employed to investigate the microbiota-mediated anti-MASLD effects of VK2. Adeno-associated virus 9 (AAV9) was used to elucidate the mechanism through which VK2 regulates MASLD severity.

VK2 significantly reduced hepatic lipid (triacylglycerol (TG) and total cholesterol (TC)) levels, as well as serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels in HFD-fed mice (p < 0.05). VK2 also significantly suppressed inflammatory responses (p < 0.05), oxidative stress (p < 0.05), and improved mitochondrial dysfunction (p < 0.05) in a GM-dependent manner. Furthermore, VK2 restored the balance in the intestinal microbiota primarily through regulating Lactobacillus spp. abundance, and markedly alleviated MASLD via a GM-dependent manner. VK2 notably upregulated the expression of SIRT3 signaling pathway proteins (p < 0.05), thereby reducing MASLD-associated mitochondrial dysfunction (p < 0.05).

VK2 exerts promising therapeutic effects mainly through enhancing intestinal Lactobacillus abundance and ameliorating mitochondrial dysfunction.

Keywords

- Vitamin K2

- MASLD

- mitochondrial dysfunction

- gut microbiota

- SIRT3 signaling pathway

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is the primary cause of chronic liver diseases. It affects 25–33% of the global population, thereby posing a significant global health challenge [1]. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH), a more severe form of MASLD, is related to hepatocellular carcinoma [2]. Several studies have indicated that the gut microbiota (GM) play a crucial role in the etiology and progression of MASLD [3, 4, 5, 6]. A prior investigation demonstrated that modulation of the gut microbiome and metabolome with Lactobacillus and Akkermansia supplement can impede the progression of MASLD [7]. Therefore, interventions targeting the GM may represent a promising therapeutic strategy for inhibiting the development of MASLD.

Vitamins are essential micronutrients for maintaining health by regulating the GM, alleviating oxidative stress, and reducing inflammation and fibrosis [4]. Hence, vitamins are considered the first-line treatment option for treating MASLD, particularly when dietary and other lifestyle changes are insufficient. Vitamin K (VK) plays a critical role in several physiological processes, and its coagulation-unrelated functions have attracted increasing interest among researchers [8]. VK1 and Vitamin K2 (VK2) are two naturally occurring isoforms of VK. VK2 is poorly absorbed into systemic circulation; nevertheless, it can regulate the GM composition to prevent certain diseases [9]. Thus, the beneficial effects of VK2 may be partially attributed to the metabolic activities of the GM [10]. However, the key gut microbial species associated with the beneficial effects of VK2 on MASLD remain elusive.

Our previous studies have revealed that VK2 can remarkably alleviate insulin resistance by improving mitochondrial dysfunction in high-fat diet (HFD)-fed mice [11]. However, the underlying mechanism through which VK2 ameliorates metabolic disorders remains unclear. In the present study, VK2 significantly enriched Lactobacillus and improved MASLD-associated mitochondrial dysfunction via the SIRT3 signaling pathway.

Eighty male C57BL/6J mice (Animal Experiment Center of Air Force Medical University, Xi’an, Shaanxi, China), aged 4–5 weeks, were randomly and equally divided into three groups and subjected to the following treatments: (1) normal diet group (n = 10): the mice were fed a standard chow diet. (2) HFD group (n = 10): the mice were provided with a high-fat diet. (3) HFD + VK2 group (n = 10): in addition to the high-fat diet, VK2 was daily administered via oral gavage at a dose of 120 mg/kg/day for the last eight weeks. The dosage of VK2 intervention was based on our previous research [10]. At the end of the experiment, mice in each group were deeply anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (100 mg/kg) and diazepam (5 mg/kg). Subsequently, liver tissues and blood samples were collected for subsequent analysis.

H&E staining, Oil Red O staining, and immunofluorescence staining with anti-CD11b antibody (GB11058, 1:100 dilution; Servicebio Technology, Wuhan, China) were conducted on paraffin-embedded and (OCT) compound-embedded frozen liver sections, as previously described in references [11, 12].

Liver tissues were lysed with radioimmuno-precipitation assay (RIPA) buffer

containing 1 mM PMSF (Beyotime Technology, Shanghai, China). Subsequently, the

lysates were centrifuged at 14,000 g for 5 minutes. The total protein

concentration was quantified using a BCA Protein Assay Kit (Beyotime Technology,

Shanghai, China). Loading buffer was added to the protein extract at a final

concentration of 5 µg/µL, and the mixture was boiled at 100

°C for 10 minutes to denature the proteins. Equal amounts of protein

were separated by electrophoresis on 10% SDS-page gels and then transferred to a

PVDF membrane. The membrane was blocked with non-fat milk and then incubated

overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies against SIRT3 (1:1000,

10099-1-AP, Proteintech, Wuhan, Hubei, China), peroxisome proliferator-activated

receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC-1

Total RNA was isolated using the Magen HiPure Universal RNA Kit (R4130-02, Magen

Biotechnology, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China), and the RNA concentration was measured with a

NanoDrop 2000C spectrophotometer. gDNA was removed from 500 ng of RNA using the

gDNA eraser (RR047Q, Takara, Kusatsu, Japan), and then the RNA was

reverse-transcribed using the PrimerScript RT Reagent Kit. qPCR targets were

normalized to

Donor feces were collected, diluted in deoxygenated saline, and filtered for inoculation into mice. Pseudo-germ-free mice were pre-treated with an antibiotic cocktail for two weeks. Subsequently, these mice were randomly divided into two groups: (1) HFD-HFD group: feces from the HFD group were administered to pseudo-germ-free HFD-fed mice; (2) VK2-HFD group: feces from the VK2 group were administered to pseudo-germ-free mice. The recipient mice were then fed a HFD for an additional 4 weeks [13].

Twenty HFD-fed mice were intraperitoneally injected with AAV-shSirt3 (1

Immediately after sacrifice, mouse liver tissues were rinsed in cold PBS and homogenized. Mitochondria were isolated through a series of dual centrifugation steps. Freshly isolated liver mitochondria were suspended in mitochondrial assay solution (MAS) [14]. One to three micrograms of mitochondria were transferred to a XFe24 microplate, which was then filled with MAS to a final volume of 500 µL, containing either glutamate/malate or succinate/rotenone. The OCR was measured in response to the sequential injection of ADP, oligomycin, FCCP and antimycin A. The respiratory rates were reported as oxygen flux per unit mass, and all readings were normalized to the micrograms of protein in the mitochondria [10, 15].

Liver tissue sections (1 mm

The contents of ATP and SOD2 were determined using an ATP Assay Kit (Beyotime, S0026) based on the luciferin/luciferase method and a Superoxide Dismutase Assay Kit with NBT (Beyotime, S0101S), following the manufacturer’s instructions. All data were measured with multimode microplate readers (Tecan Infinite 200 PRO, Tecan Life Sciences, Männedorf, Switzerland). Briefly, liver tissue homogenates were centrifuged at 12,000 g for 5 minutes at 4 °C. The supernatant was collected and used for the detection of ATP and SOD2 levels. The luminescence was measured using multimode microplate readers (Tecan Infinite 200 PRO).

Mitochondria were extracted from fresh liver tissues, and the activities of mitochondrial respiratory complexes I and IV were measured using the corresponding kits from Abcam MitoSciences (Cambridge, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Appropriate statistical methods were employed using SPSS software (Version 22, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). One-way and two-way ANOVA were conducted for multiple comparisons, while Student’s t-test was utilized for comparisons between two groups. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

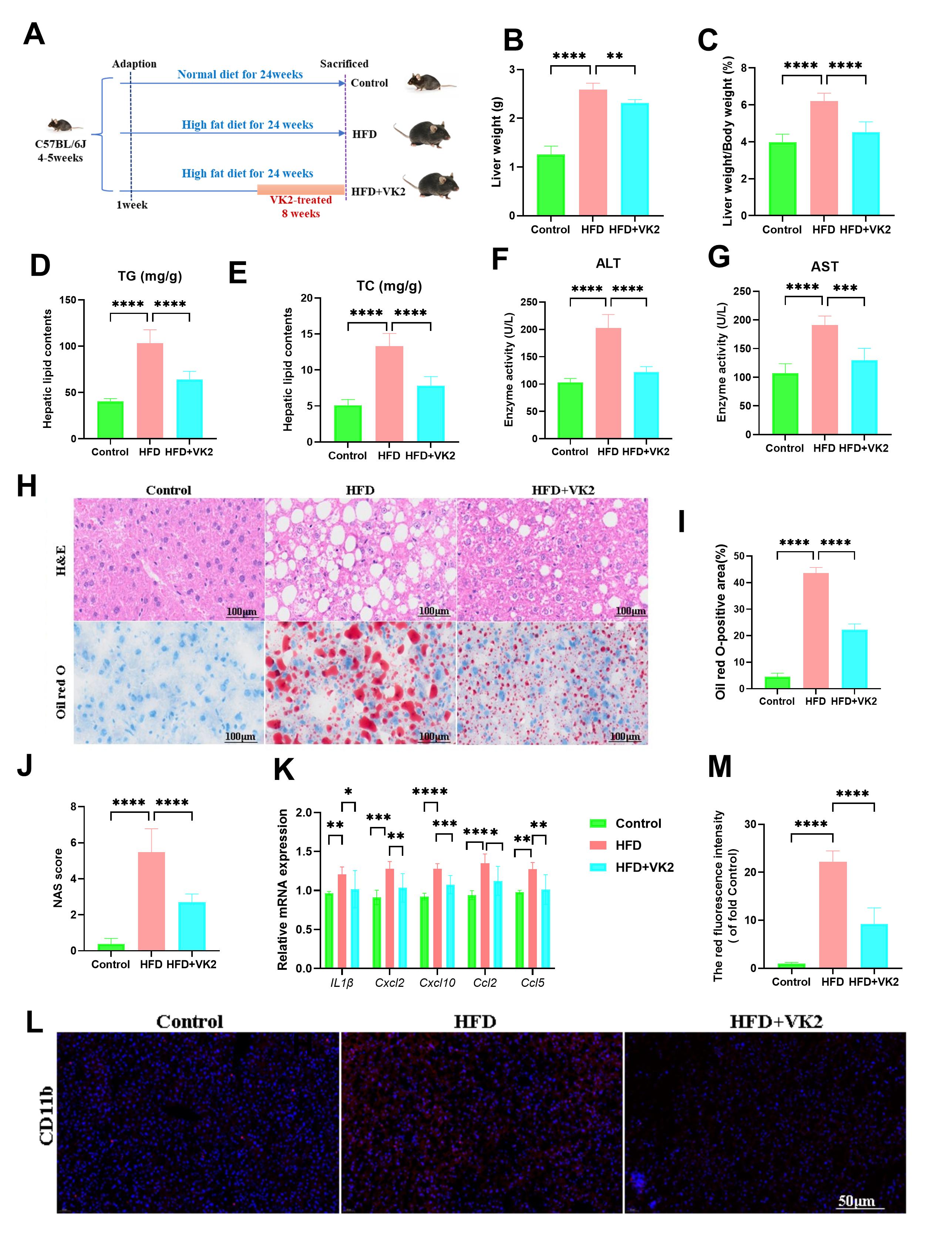

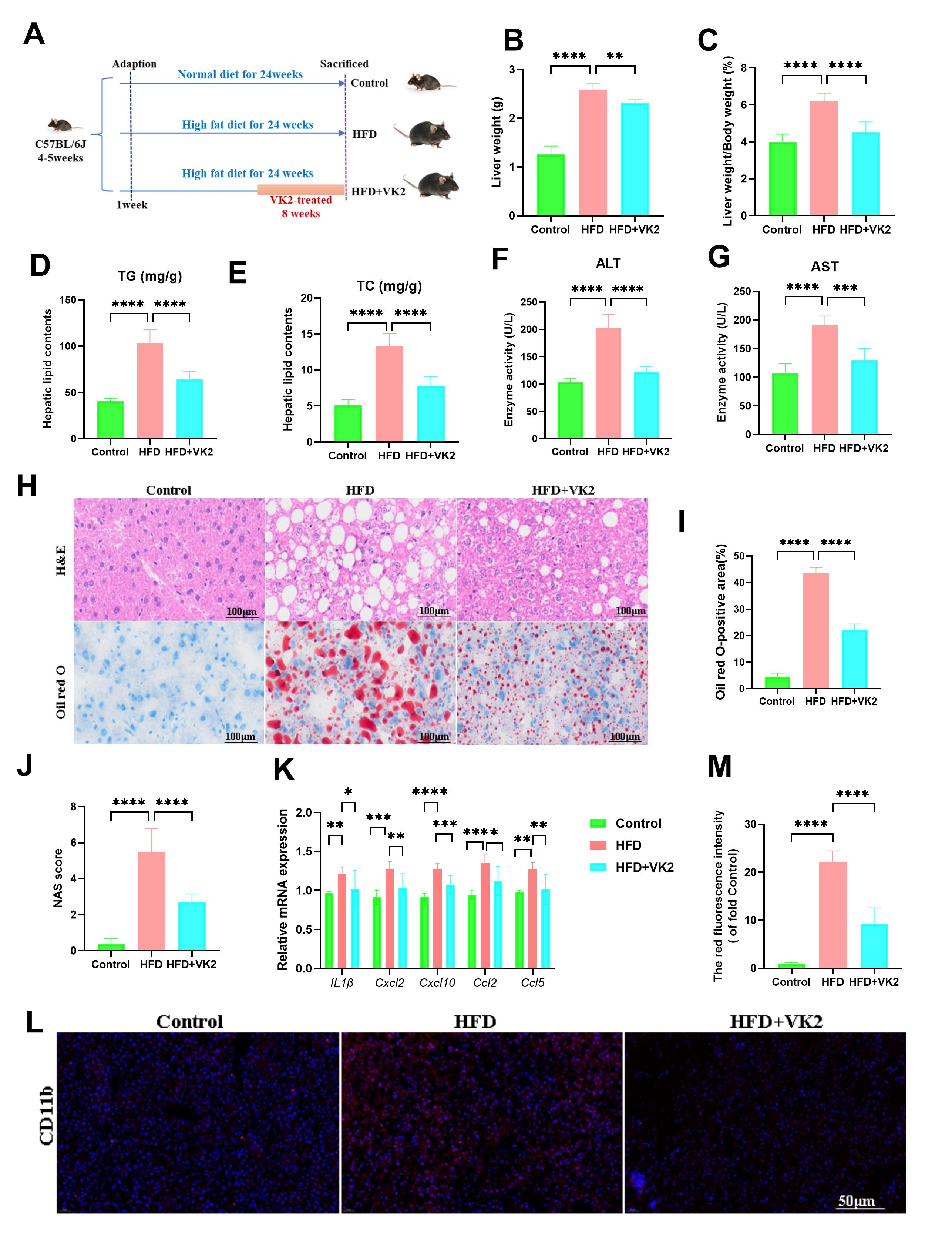

To investigate the effects of VK2 on MASLD, C57BL/6J mice were fed a HFD for 16

weeks, followed by oral administration of VK2 (120 mg/kg/day) while continuing

the HFD for an additional 8 weeks (Fig. 1A). Compared with the control group,

HFD-fed mice exhibited a significant increase in body weight over time. Both

liver weight (LW) and the LW-to-body weight (LW/BW) ratio were significantly

lower in the VK2-treated group when compared to the HFD group (Fig. 1B,C).

Hepatic triglyceride (TG) and total cholesterol (TC) levels were also

significantly reduced in VK2-treated mice (Fig. 1D,E). Given that lipotoxicity

can lead to hepatocyte injury or death [16], serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT)

and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels were elevated after 24 weeks of HFD

feeding. However, VK2 treatment significantly lower serum ALT and AST levels

compared to the HFD group (Fig. 1F,G). Hepatic histology revealed that VK2

reduced HFD-induced hepatic ballooning and lipid droplet accumulation (Fig. 1H–J). VK2 treatment suppressed the expression of inflammatory genes

(IL-1

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

VK2 attenuates HFD-induced MASLD. (A) Schematic of VK2 gavage

intervention. (B,C) LW and LW/BW ratios in all groups. n = 10 per group. (D,E) TG

and TC levels in hepatic tissues. n = 10 per group. (F,G) Serum ALT and AST

levels. n = 10 per group. (H–J) Representative images of H&E staining, Oil Red

O staining, and MASLD activity score to evaluate hepatic steatosis and lipid

accumulation. n = 6 per group. Scale bar = 100 µm. (K) Relative mRNA

expression levels of inflammatory genes (IL-1

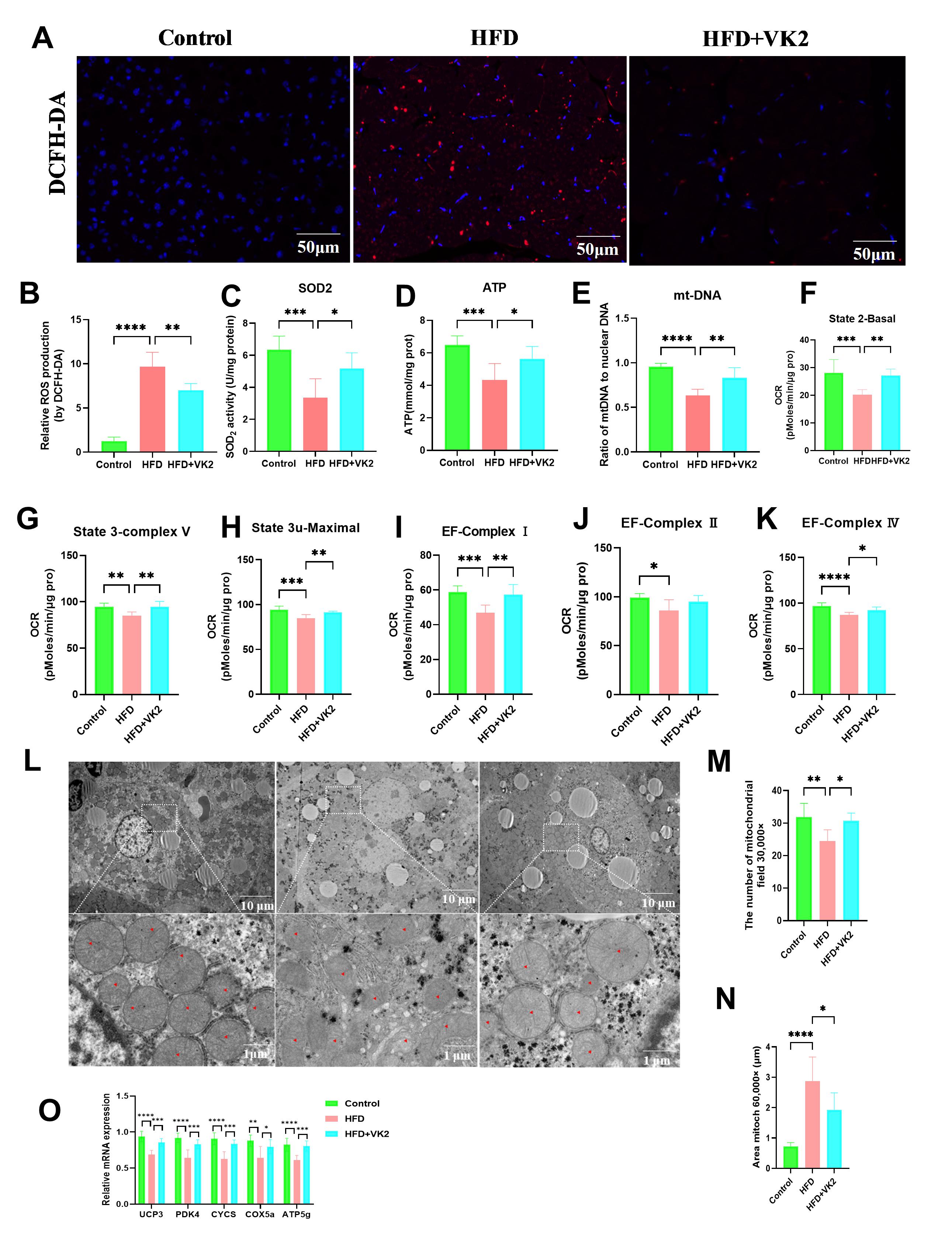

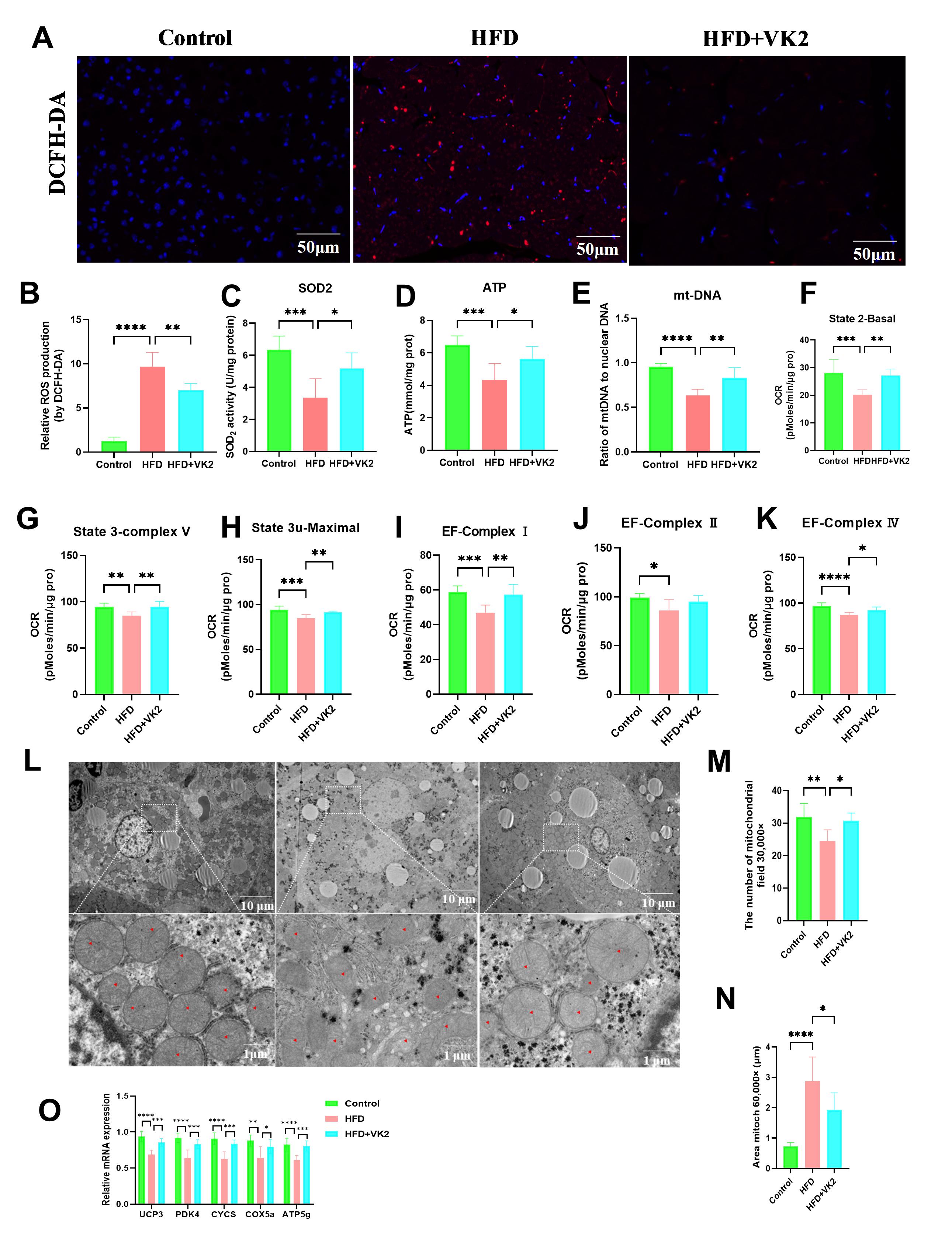

Mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to MASLD progression. Increased free fatty acid (FFA) influx into hepatocytes induces metabolic changes that impair mitochondrial function [17]. VK2 treatment significantly reduced HFD-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, as measured by DCFH-DA staining (Fig. 2A,B). Furthermore, VK2 treatment significantly enhanced ATP content, mitochondrial-DNA (mtDNA) gene expression, and SOD2 enzyme activity, suggesting that VK2 alleviated oxidative stress in HFD-fed mice (Fig. 2C–E). To further assess mitochondrial function, we measured bioenergetic parameters. Compared with the HFD group, VK2 treatment enhanced overall mitochondrial activity in the liver, restoring mitochondrial dysfunction and improving basal respiration and spare respiratory capacity in HFD-fed mice (Fig. 2F–K). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) revealed that HFD-fed mice exhibited abnormal mitochondria with displaced myofibrils, swelling, and vacuole-like degeneration compared to the control group (Fig. 2L). In contrast, VK2-treated mice showed a significant increase in the total number and a decrease in average mitochondria area (Fig. 2M,N). Consistently, VK2 treatment upregulated the expression of mitochondrial biogenesis genes (Fig. 2O). Collectively, these findings indicate that VK2 ameliorates mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

VK2 improves oxidative stress and mitochondrial function in

HFD-fed mice. (A,B) Hepatic reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels measured by

DCFH-DA staining and quantification of relative ROS production. n = 6 per group.

Scale bar = 50 µm. (C–E) Hepatic superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) enzyme

activity (C), ATP content (D), and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) copy number

(mtDNA/nuclear DNA ratio) (E) in the liver tissue. n = 7 per group. (F–K) Oxygen

consumption rate (OCR) of isolated liver mitochondria to assess mitochondrial

bioenergetic. Basal respiration was measured under State 2 (F), State 3 (G), and

State 3u (H) conditions. Electron transport chain complex activity was determined

for complex Ⅰ (I), complex Ⅱ (J), and complex Ⅳ respiration (K). n = 6 per group.

(L) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of hepatic mitochondria (red

triangle indicate mitochondrial structures). Images were acquired at

10,000

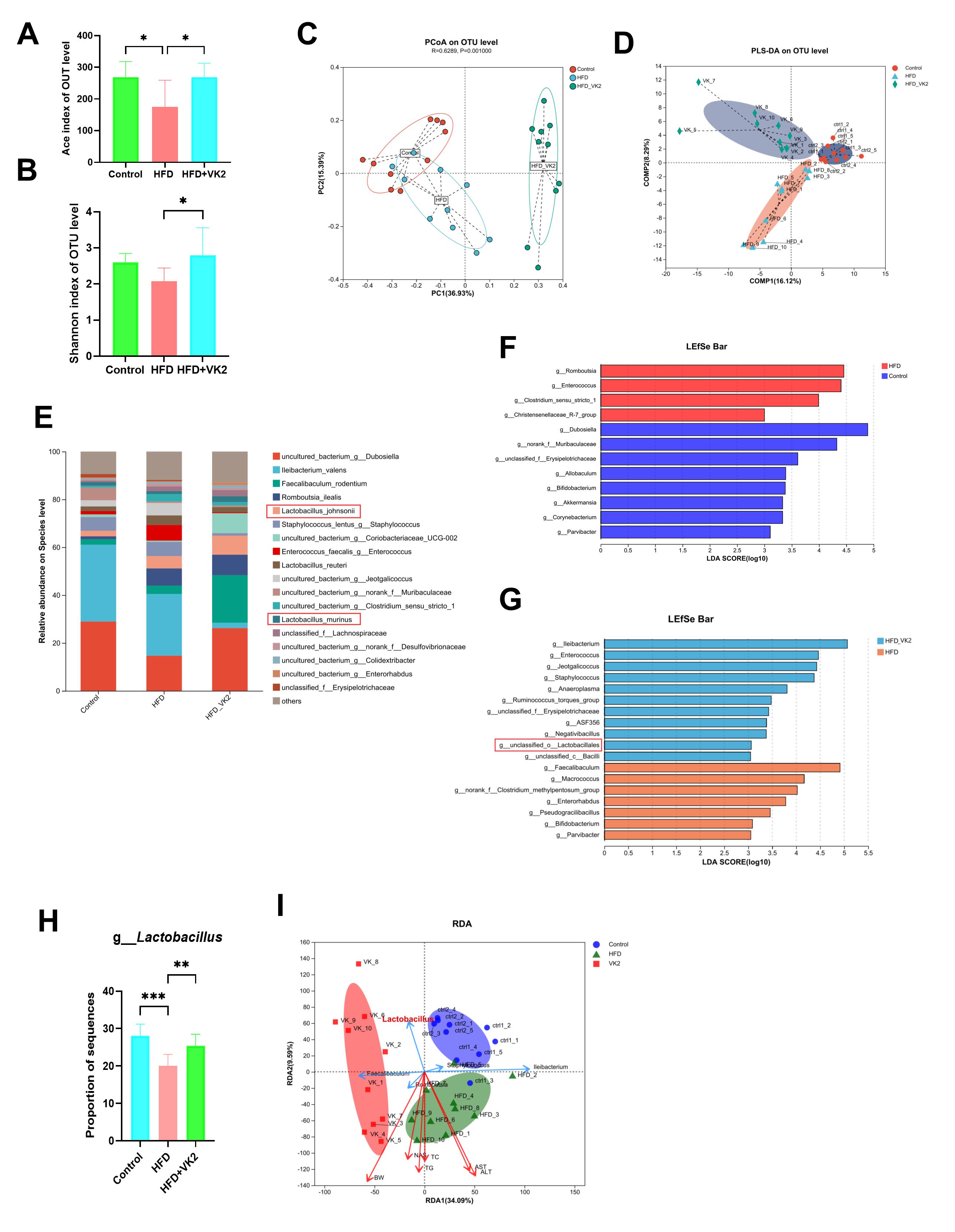

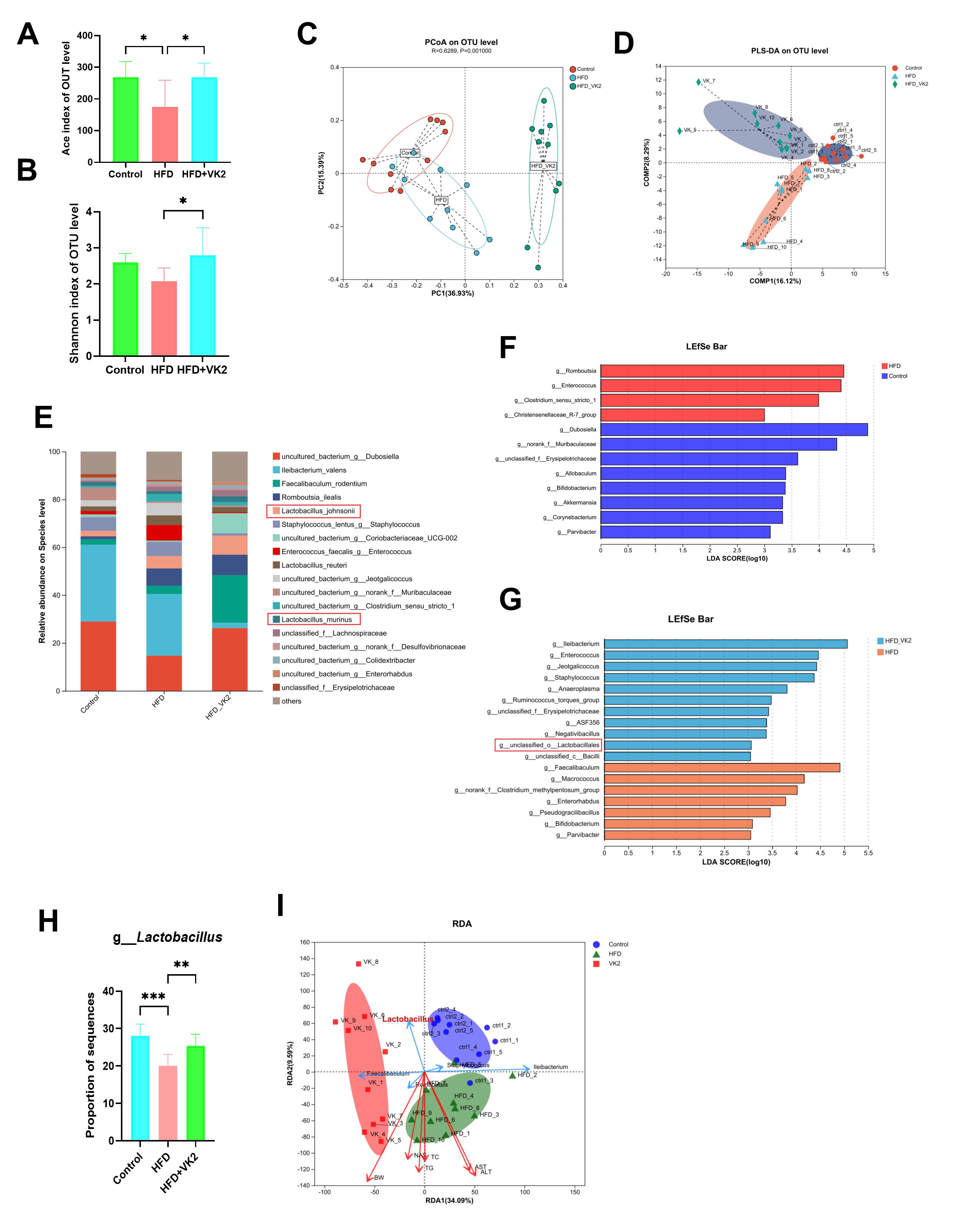

Given that the GM contributes to MASLD progression, we investigated the effect of VK2 treatment on GM composition. Compared with the HFD group, the VK2-treated group exhibited a significant increase in the Ace and Shannon indices (Fig. 3A,B), indicating that VK2 treatment restored reduced gut microbial diversity in HFD-fed mice. UniFrac-based principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) and partial least squares-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) revealed distinct clustering of microbial communities among groups (Fig. 3C,D). The relative abundance of bacterial species Lactobacillus johnsonii and Lactobacillus murinues were significantly increased by VK2 treatment compared with the HFD group (Fig. 3E) [18]. To identify specific bacterial taxa altered by VK2 supplementation, linear discriminant analysis (LDA) effect size (LEfSe) was utilized to compare the fecal microbiota composition at the genus level. Compared with the control group, HFD group showed lower abundance of Dubosiella, norank_f__Muribaculaceae, unclassified_f__Erysipelotrichaceae Allobaculum, Bifidobacterium, Akkermansia, Corynebacterium, Parvibacter but a higher abundance of Rombountsia, Enterococcus, Clostridium_sensu_stricto_1, Christensenellanceae_R-7_group (Fig. 3F). Conversely, the HFD group enriched Ileibacterium, Enterococcus, Jeotgalicoccus, Staphylococcus, Anaeroplasma, Ruminococcus_torques_group, unclassified_f_Erysipelotrichaceae, ASF356, Negativibacillus, unclassified_c_Lactobacillales, unclassified_c_Bacilli, whereas VK2 treatment increased the abundance of Faecalibaculum, Macrococcus, norank_f__Clostridium_methylpentosum_group, Enterorhabdus, Pseudogracilibacillus, Bifidobacterium, Parvibacter in HFD-fed mice (Fig. 3G). At the genus level, the HFD group exhibited a significant decrease in Lactobacillus relative abundance compared with the control group, whereas VK2 treatment significantly restored Lactobacillus abundance (Fig. 3H). Redundancy analysis (RDA) showed that Lactobacillus was significantly negatively correlated with MASLD-associated parameters (hepatic TC, TG, serum ALT, AST, and NAS score) (Fig. 3I); suggesting that Lactobacillus enrichment may be mediate the protective effects of VK2 against MASLD. Collectively, these results indicate that VK2 reverses gut dysbiosis in HFD-induced MASLD.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

VK2 mitigates gut dysbiosis in HFD-induced MASLD. Fresh fecal

samples were collected from mice after 4 weeks of VK2 treatment for 16S rRNA gene

sequencing analyses. (A) Ace and (B) Shannon diversity indices of the GM. (C,D)

Weighted UniFrac PCoA analysis and PLS-DA analysis of microbial communities. (E)

Relative abundance of bacterial genera at the genus level. (F,G) LEfSe was used

to identify differentially abundant taxa in the GM. (H) Relative abundance of

Lactobacillus across all groups. (I) RDA analysis of the correlation

between Lactobacillus and MASLD-associated parameters. All data are

expressed as mean

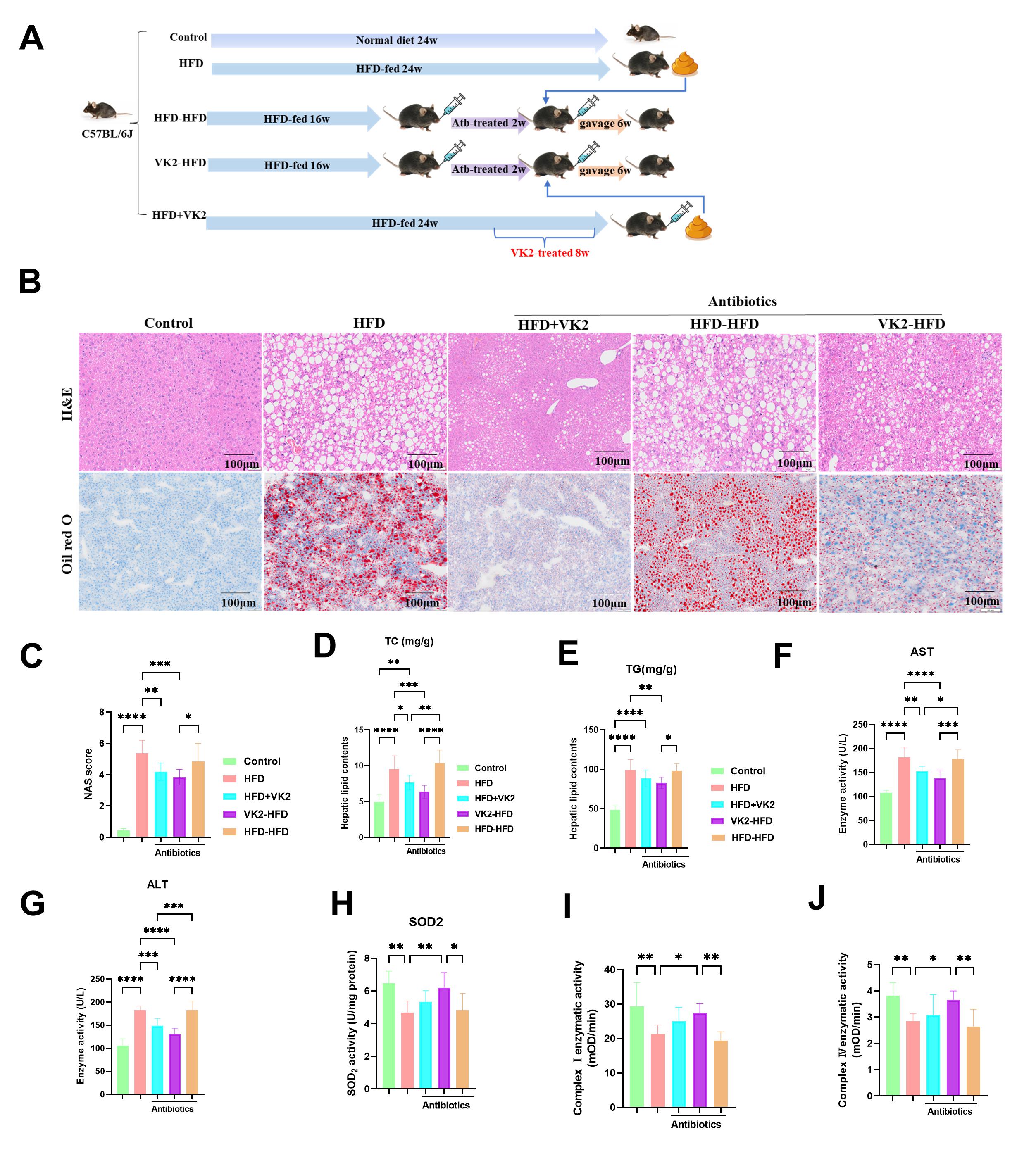

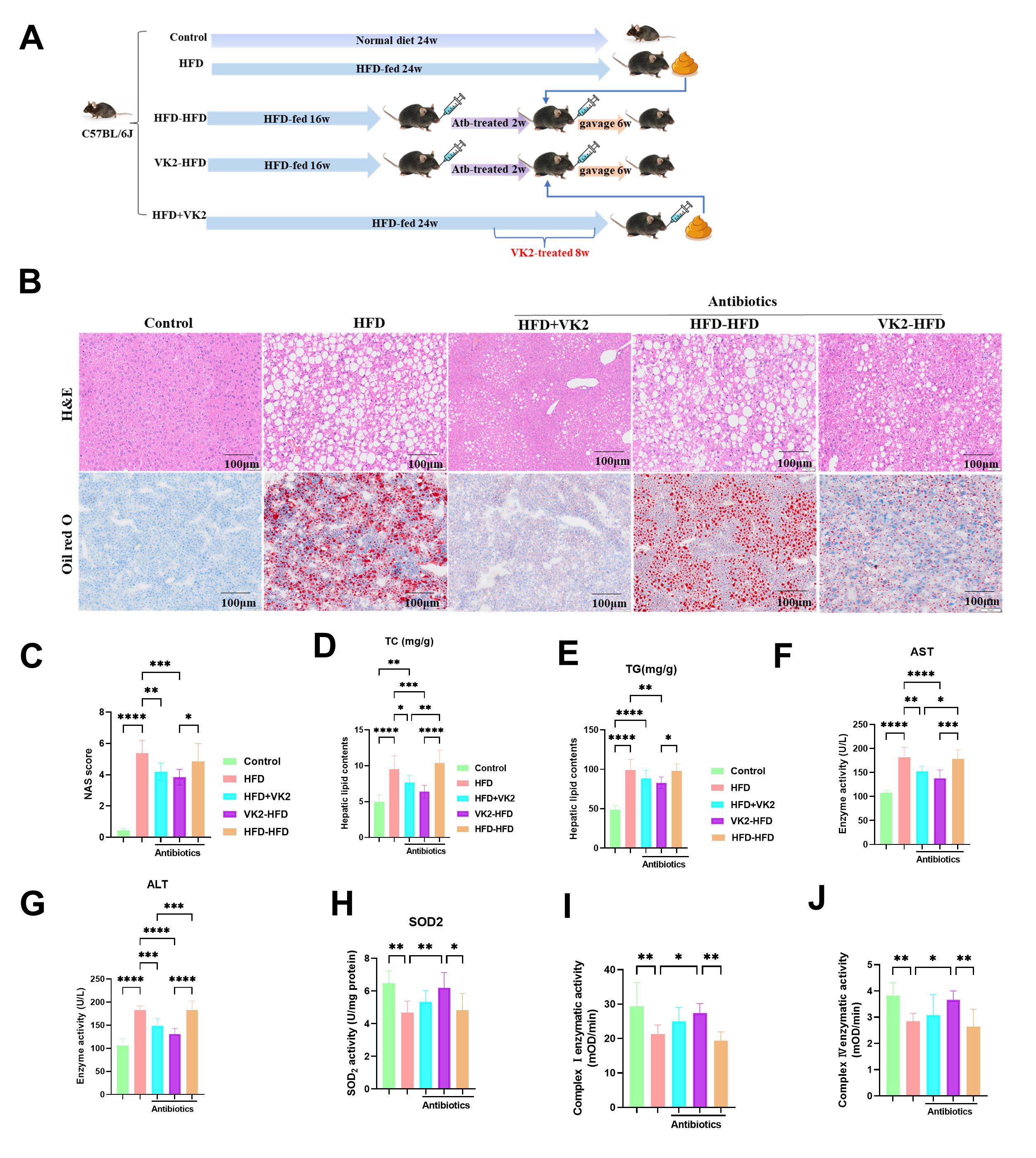

To determine whether the beneficial effects of VK2 in HFD-fed mice are dependent on the GM, we transplanted fecal microbiota from VK2-treated HFD-fed donor mice to recipient HFD-fed mice via daily gavage. Recipient mice were pre-treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics in drinking water for 2 weeks to generate conditionally pseudo germ-free mice (Fig. 4A). Following the fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), recipient mice that received VK2-treated microbiota exhibited significantly lower NAS scores (Fig. 4B,C), accompanied by reduced hepatic lipid levels (TC and TG) (Fig. 4D,E), decreased serum AST and ALT levels (Fig. 4F,G), and enhanced SOD2 activity (Fig. 4H) and mitochondrial respiratory complex Ⅰ and Ⅳ activity (Fig. 4I,J). These findings demonstrated that fecal microbiota transplantation (FTM) from VK2-treated donor recapitulated the beneficial effects of VK2, including reduced oxidative stress and improved mitochondrial function in the liver of HFD-fed mice. Collectively, these data indicate that VK2 ameliorates MASLD via a GM-dependent mechanism.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

VK2 attenuates MASLD in a GM-dependent manner. (A) Schematic of

the FTM study. (B,C) H&E staining and Oil Red O staining were used to determine

hepatic steatosis and lipid accumulation, and the MASLD activity score. n = 6 per

group. Scale bar = 100 µm. (D,E) Hepatic TG and TC levels. n = 10

per group. (F,G) Serum ALT and AST levels. n = 10 per group. (H) Hepatic SOD2

activity was measured. n = 7 per group. (I,J) Activity of hepatic mitochondrial

respiratory complex Ⅰ and Ⅳ. n = 7 per group. One-way ANOVA was used to analyze

data. Significant differences were observed between the control and HFD-fed

groups, and between the HFD group and the groups treated with VK2 along with

antibiotics plus HFD or the FMT group. *p

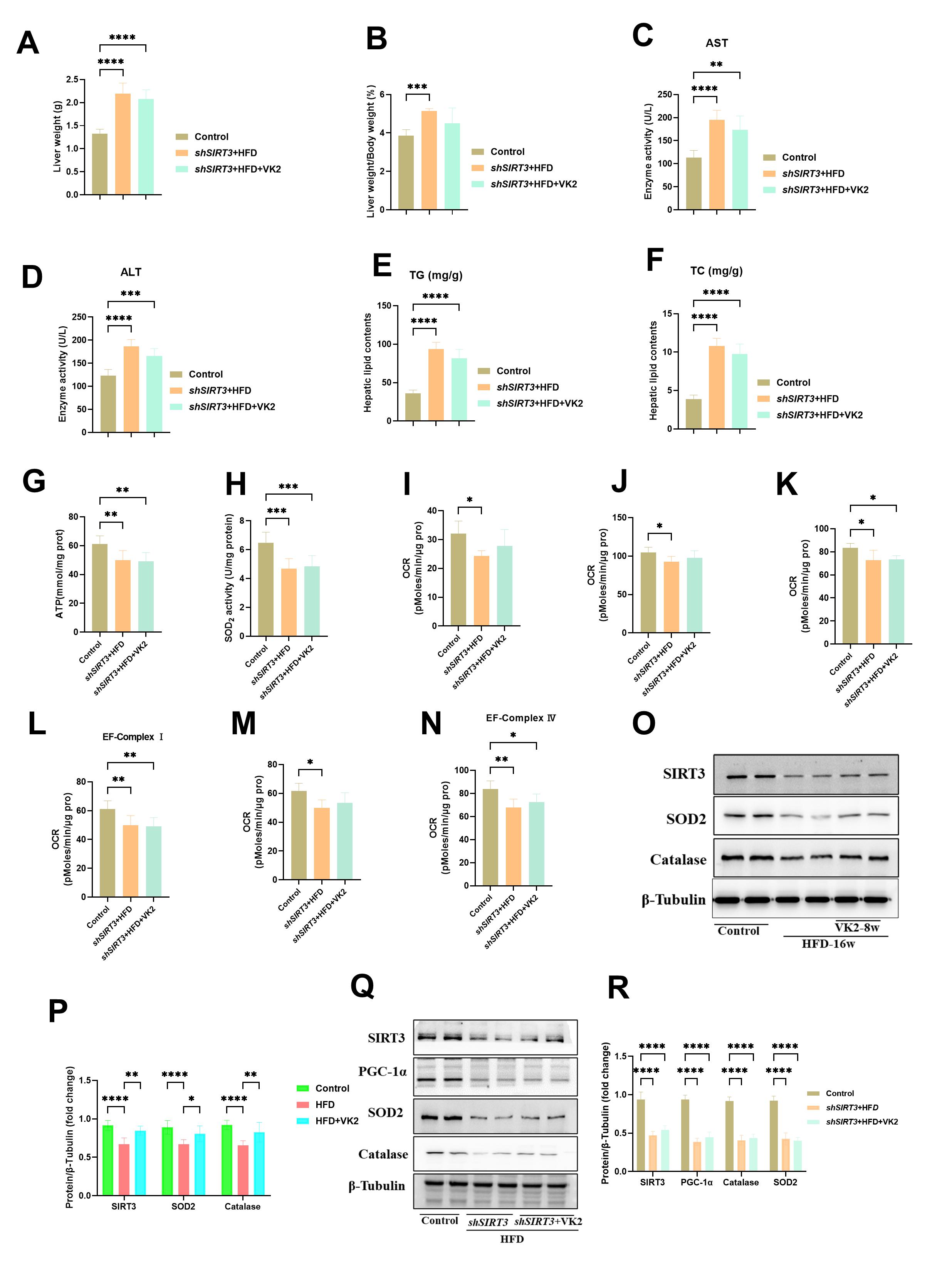

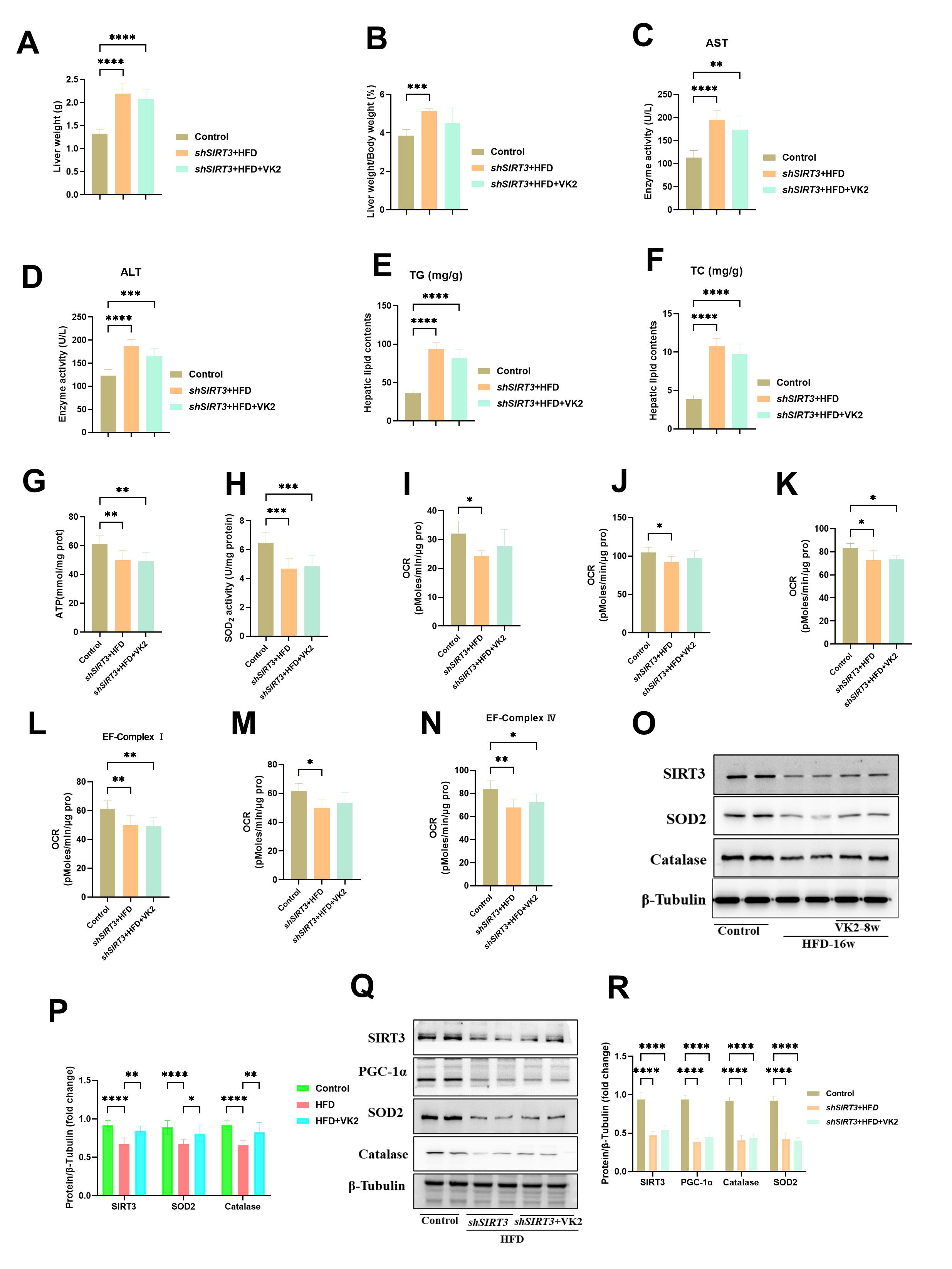

Our previous studies have revealed that VK2 can significantly alleviate insulin

resistance by improving mitochondrial dysfunction in HFD-fed mice via SIRT3

signaling. To determine whether SIRT3 mediates the effect of VK2 on mitochondrial

function in vivo, we knocked down the gene encoding SIRT3 in the livers

of mice by delivering shRNA using adeno-associated virus 9. SIRT3

knockdown reduced the effect of VK2 on the LW/BW ratio (Fig. 5A,B), activities of

AST and ALT (Fig. 5C,D), and hepatic lipid levels (TG and TC) (Fig. 5E,F).

Moreover, the ATP level and SOD2 enzyme activity were not significantly improved

by VK2 treatment in HFD-fed mice with SIRT3 knockdown (Fig. 5G,H).

Additionally, VK2 did not enhance the mitochondrial basal respiration and spare

respiratory capacity in HFD-fed mice with SIRT3 knockdown (Fig. 5I–N).

VK2 treatment increased the protein expression levels of SIRT3, SOD2, and

catalase in the liver tissues of HFD-fed mice (Fig. 5O,P). However,

SIRT3 knockdown abolished the effect of VK2 on mitochondrial function

and the protein expression of SIRT3, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC-1

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

VK2 improves mitochondrial activity through SIRT3 signaling

pathway. (A,B) LW and the LW/BW ratio. (C,D) Serum ALT and AST levels. n = 10

per group. (E,F) TG and TC levels. n = 8 per group. (G,H) Hepatic ATP contents

and SOD2 enzyme activity. n = 7 per group. (I–N) OCR of isolated liver

mitochondria to assess mitochondrial bioenergetic. Basal respiration was measured

under State 2 (I), State 3 (J), and State 3u (K) conditions. Electron transport

chain complex activity was determined for complex Ⅰ (L), complex Ⅱ (M), and

complex Ⅳ (N). n = 6 per group. (O,P) Protein expression of SIRT3, SOD2 and

catalase were determined in all groups. n = 7 per group. (Q,R) Protein expression

of SIRT3, PGC-1

MASLD is the leading chronic liver disease worldwide. The GM has been recognized as a key mediator in the pathogenesis and progression of MASLD, primarily through regulation host energy metabolism and metabolic homeostasis [19, 20]. Although previous studies have shown that VK2 acts as an effective antioxidant and anti-inflammatory micronutrient in treating HFD-induced insulin resistance [10], the underlying mechanisms by which VK2 exerts its effects remain poorly understood, and whether VK2 functions through a GM-dependent mechanism has not been explored. The present study demonstrated that VK2 significantly ameliorated mitochondrial dysfunction in HFD-fed mice by regulating the GM, particularly by increasing the abundance of Lactobacillus. VK2 treatment significantly activated the SIRT3 signaling pathway, thereby mediating the alleviation of mitochondrial dysfunction.

Vitamins have well-established roles in bacterial metabolism. VK is a less understood mediator of both vitamin-GM interactions and community dynamics. The VK requirement in humans is met through the diet, which may involve the influence on the composition of GM by dietary components [21]. VK1 is present in leafy green vegetables [22]. VK2 is present in dairy products and fermented foods [23], menaquinone-4 (MK-4) is a homolog of VK2, is the major form of VK in animal tissues and is produced by the GM [24]. The relevance of MK-4 produced by gut bacteria to human health has long been speculated [25]. VK act as a cofactor for the carboxylation of VK-dependent proteins, which are involved in diverse functions [26]. Historically, gut bacteria have been considered to contribute up to 50% of the host’s VK requirement. However, the underlying mechanisms by which VK alleviates mitochondrial dysfunction and exerts an anti-inflammatory effect remain elusive [27]. Additionally, a previous study demonstrated that vitamin B12 is similarly metabolized by gut bacteria and serves as a modulator of gut microbial ecology [28]. Collectively, these findings enhance our understanding of micronutrient-microbiota interactions.

VK2 functions as an electron carrier in bacterial respiration [9]. Mice with VK deficiency exhibited lower relative abundance of Lactobacillus than those fed a VK2-supplemented diet [9]. Lactobacillus species are known to enhance the intestinal epithelial barrier function and tight junction integrity, thereby playing a beneficial role in protecting the gut mucosal barrier [29, 30]. Species Lactobacillus strains, such as L. rhamnosus, L. acidophilus, and L. bulgaricus, have been shown to reduce serum transaminase levels, alleviate hepatic steatosis, and decrease the MASLD activity score (NAS) [29, 30]. Additionally, other Lactobacillus species (e.g., L. gasseri) exert protective effects by mitigating tight junction proteins disruption and enhancing intestinal barrier function [31, 32]. Our study revealed that VK2 supplementation exerts a novel role in modulating GM composition, whereby VK2 administration enriches the relative abundance of Lactobacillus and alleviates MASLD-related pathological phenotypes in HFD-fed mice. These findings align with previous reports of GM composition changes following VK supplementation and highlight the critical role of the microbiota in mediating VK2’s therapeutic effects against MASLD.

In this study, VK2 treatment upregulated hepatic SIRT3 protein expression. SIRT3 plays protective role in aging, diabetes, obesity, hypertension, and MASLD [33, 34, 35]. Consistent with these observations, SIRT3 knockdown abolished the beneficial effects of VK2 on oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction. Mechanistically, VK2 treatment significantly enriched the commensal bacterium Lactobacillus and activated the SIRT3 signaling pathway, linking microbial modulation to mitochondrial protection.

Our research first demonstrated that VK2 improves mitochondrial dysfunction in HFD-fed mice by activating the SIRT3 signaling pathway and alleviates HFD-induced MASLD through GM regulation, particularly by increasing the abundance of Lactobacillus. However, several limitations merit consideration. First, while our study revealed that VK2’s effect on mitochondrial function may be correlated with other mitochondrial pathway (e.g., AMPK signaling cascades), we only characterized the SIRT3 signaling-dependent beneficial effects. Second, although we focused on VK2-mediated enrichment of Lactobacillus, the role of gut microbial metabolites in this process remains unexplored and could be further investigated using high-resolution mass spectrometry. Third, we did not include a normal diet group treated with VK2 to rule out the potential impact of VK2 itself on normal liver. Additionally, the effect of Lactobacillus supplementation alone on HFD-fed mice MASLD mice was not examined, which would help clarify the causal role of this genus in VK2’s therapeutic effects.

The current study demonstrated that Vitamin K2 (VK2) significantly ameliorated the symptoms of MASLD through a GM dependent mechanism. VK2 treatment rectified the microbial dysbiosis and alleviated MASLD by activating the SIRT3 signaling pathway. Additionally, VK2 treatment reduced MASLD symptoms by enhancing the abundance of beneficial Lactobacillus species, thereby promoting their dominant colonization within the intestinal tract. Collectively, these results uncover a novel role of VK2 in the context of MASLD. The findings of this research may offer a promising therapeutic strategy for the treatment of MASLD by targeting key microbial metabolites or specific gut bacterial species.

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

XS: Investigation, Writing—review & editing, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision. PS and WW: Data curation, Writing—original draft, Formal analysis. JL, LM, YB and MZ: Reviewing, Data analysis and Interpretation as well as Writing—original draft. SH, YZ and JW: Methodology and drafting the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

All procedures performed in studies involving animals were in accordance with the ethical standards of Ethics Committee in the Air Force Medical University (NO. IACUC20141259).

We thank our research and medical staff for making this study possible.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.82103810) and Outstanding Young Director in Air Force Medical University (4457475042JZ2300U0).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.