1 Center of Metabolism and Nutrition of Cancer, Beijing Shijitan Hospital, Capital Medical University, 100038 Beijing, China

2 Department of Pharmacy, Beijing Shijitan Hospital, Capital Medical University, 100038 Beijing, China

3 Department of Critical Care Medicine, Beijing Shijitan Hospital, Capital Medical University, 100038 Beijing, China

4 School of Molecular Sciences, University of Western Australia, Perth, WA 6009, Australia

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

This study aimed to determine whether administering intravenous vitamin C in patients with malignant neoplasm is associated with increased survival outcomes compared to no intravenous vitamin C administration.

The primary search was conducted using MEDLINE (via PubMed), Embase, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) databases from inception to October 13, 2024. Results were collected from randomized clinical trials and cohort studies that compared intravenous vitamin C and blank controls or placebo in patients with malignant neoplasm. Two reviewers independently assessed the data extraction process and the risk of bias, while the certainty of evidence was evaluated using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation approach. A frequentist framework was used as the primary analysis approach.

A total of 8 studies with 2722 adult participants were included. The vitamin C dose ranged from 2.5 g/d to 1.5 g/kg of body weight per day, with the treatment duration ranging from 9 days to 1 year. The primary outcome was overall survival, with progression-free survival as a secondary measure. Intravenous vitamin C was associated with a significantly longer median overall survival (pooled estimated median survival ratio: 1.83; 95% confidence interval: 1.40–2.40; p < 0.001; moderate certainty), and a trend towards improved progression-free survival (pooled estimated median survival ratio: 1.80; 95% confidence interval: 0.95–3.41; p = 0.073). Subgroup analyses of overall survival showed higher median survival ratios with vitamin C doses <1 g/kg (vs. ≥1 g/kg), in non-Chinese regions (vs. Chinese regions), with non-chemotherapy combinations (vs. chemotherapy combinations), and in cohort studies (vs. randomized controlled trials).

The administration of intravenous vitamin C to adults with malignant neoplasm was associated with a longer median overall survival compared to no vitamin C administration. The current evidence indicates a moderate degree of certainty for considering intravenous vitamin C as a standard of care in managing malignant neoplasms.

CRD42024600634, https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD42024600634.

Keywords

- vitamin C

- ascorbic acid

- malignant neoplasms

- survival

- meta-analysis

The concept that vitamin C could be utilized for the treatment of malignant neoplasms has been highly controversial over the past century [1, 2]. However, an improved understanding of the pharmacokinetics of vitamin C has reignited interest in this therapeutic approach [1]. Specifically, mM levels of vitamin C, which are cytotoxic to cancer cells, can only be achieved via intravenous administration and not through oral dosing. In light of these findings, numerous clinical studies have been launched in recent years, with some already completed and reporting promising results.

The main mechanisms involving high-dose vitamin C in cancer therapy include: (1) exploitation of the redox imbalance in cancer cells to induce cell death by generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) and hydroxyl radicals (•OH); (2) epigenetic reprogramming of cancer cells to activate ten-eleven translocation (TET) enzymes, promote DNA demethylation, and restore the expression of tumor suppressor genes; and (3) inhibiting the hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF1) signaling pathway to reduce the ability of tumor cells to adapt to hypoxia, thereby suppressing tumor growth [1].

Wang et al. [3] conducted the first randomized, multicenter, phase III clinical trial to investigate the efficacy and safety of high-dose vitamin C combined with folinic acid, fluorouracil, and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX)

Vitamin C has also been found to alleviate chemotherapy-induced side-effects, such as nausea, vomiting, and fatigue, thereby improving the patients’ quality of life [8, 9]. However, these effects have yet to be confirmed in all patient groups. In contrast, oral vitamin C has more limited effects, with multiple studies finding that it has no significant impact on OS, disease progression, or symptom relief in cancer patients [10]. This may be related to the lower bioavailability of oral vitamin C, which makes it difficult to achieve pharmacological levels in the body. In addition, some studies have found that oral vitamin C may have a negative impact on the efficacy of certain chemotherapy drugs by reducing their effectiveness or increasing chemotherapy-related toxicity [10]. Despite this, vitamin C treatment is relatively safe, with no serious adverse effects reported [8, 9, 10]. Most studies have shown that patients tolerate vitamin C well, with only mild side-effects such as nausea, vomiting, and injection site discomfort being reported. These side-effects are usually related to the dose and administration method of vitamin C, and in most cases are quite manageable.

Despite numerous clinical studies [2] and several systematic reviews [8, 9, 10], no meta-analysis has yet been performed to quantitatively evaluate the efficacy of IVC in the treatment of malignant neoplasms. The present study is the first meta-analysis aimed at assessing the OS and PFS of adult patients with malignant neoplasms who received IVC compared to those who did not. We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and cohort studies, and compared the outcomes following IVC with no treatment or placebo. Our analysis revealed that administration of IVC was associated with longer median overall survival compared to no IVC. The current evidence indicates there is a moderate degree of certainty with regard to the use of IVC as standard care for malignant neoplasms.

A systematic review and meta-analysis encompassing both RCTs and cohort studies was carried out following a prespecified protocol (Supplementary Document 1). The findings of this review were reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement [11], and the study was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (registration number CRD42024600634).

The analysis included RCTs and cohort studies that targeted adult patients diagnosed with malignant neoplasms, and specifically those that compared the efficacy of IVC administration to a control group that did not receive any vitamin C treatment. Malignancy was strictly defined based on pathological diagnoses and other established standard diagnostic criteria applicable at the time of patient recruitment. The administration of vitamin C was characterized by a series of repeated intravenous infusions that followed predetermined doses and schedules, and which contrasted with the control group that received no vitamin C intervention at all.

A thorough search was performed across MEDLINE (via PubMed), Embase, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) databases up to October 13, 2024. This search included studies in all languages and was not restricted by publication date or status. The search strategy utilized a carefully crafted combination of keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) to locate studies related to “neoplasms”, “tumors”, “neoplasia”, “cancer”, “malignant neoplasm”, and various forms of vitamin C, including “ascorbic acid”, “L-ascorbic acid”, “ferrous ascorbate”, and “sodium ascorbate” among others. Additionally, the search focused on the term “survival”, and included both RCTs and cohort studies.

Additional studies were identified by manually reviewing references from the included studies and relevant systematic reviews. Further details regarding the electronic search strategy are given in Supplementary Document 2.

The titles and abstracts from the search were filtered using EndNote [12]. Duplicates and irrelevant studies were excluded. A minimum of two reviewers (JQ, MY, or SY) independently screened all identified references for inclusion. Reports that were deemed as possibly meeting the inclusion criteria, identified by either reviewer, were retrieved for full-text evaluation. A minimum of two reviewers (JQ, MY, or SY) independently evaluated the full text of potentially eligible studies for inclusion. When disagreements arose, these were resolved via discussion or by consulting with a third reviewer, if required (YW, SL, or BW). The selection process was recorded and reported in a PRISMA flow diagram.

Two reviewers (JQ and MY) independently gathered information from each included study utilizing a standardized data extraction form. Inconsistencies were addressed through discussion, and if necessary advice was sought from a third reviewer (SY). Data extraction followed the established protocol (Supplementary Document 1) and included details on disease diagnosis, study region, outcomes, dosing and frequency of IVC, concurrent therapies, and study design. No imputation was performed for any missing data.

The Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool for randomized trials version 2 [13] was used to evaluate the risk of bias in each randomized trial included in the analysis. This tool examines various potential biases that could significantly affect the results of RCTs, focusing on five key areas: the randomization process, deviations from the intended interventions, missing outcome data, outcome measurement, and the selection of reported results. Each study was systematically assessed and categorized into one of three classifications: “low risk of bias”, “some concerns”, or “high risk of bias”. The proposed judgment for each study was generated using a detailed algorithm according to the responses to the signaling questions provided in the tool, thus ensuring comprehensive and objective evaluation.

The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale [14] was employed to evaluate potential bias in cohort studies, focusing on three key criteria that allow for a maximum score of 9 stars. The first criterion, “study selection”, can earn up to 4 stars. The second criterion, “group comparability”, contributes 2 stars, while the third, “outcome ascertainment”, can yield 3 stars. Based on their scores, the studies were subsequently categorized into quality levels. Those scoring 4 stars or fewer were considered low quality, those with scores between 5 and 7 stars were considered medium quality, while studies achieving 8 or 9 stars were recognized as high quality.

The assessment of bias risk was conducted by two independent evaluators (JQ and MY) who were not involved in the selection of studies for this analysis. Any disagreements that arose during the assessment were resolved through discussions aimed at reaching a consensus. If necessary, advice from a third reviewer (SY or YW) was sought to finalize the assessment.

The main outcome of the study was OS, defined as the duration from the point of randomization until death due to any reason. The secondary outcome focused on PFS, defined as the period from randomization to the initial occurrence of disease progression or death due to any reason.

Pooled estimates of effect size, represented as median survival ratios (MSRs) for the median survival times, were accompanied by the corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) to give a clear overview of the findings [15]. A random-effects model, utilizing DerSimonian-Laird estimates of the between-study variance, was selected in advance for all analyses due to anticipated differences in trial design and in the implementation of interventions across studies [16]. The heterogeneity between included studies was assessed using the Cochran Q test and the Higgins I2 statistic, which offer important insights into the variability of study outcomes [17, 18]. Additionally, publication bias was evaluated both qualitatively through visual inspection of the funnel plot, and quantitatively using the Egger test, enabling a comprehensive investigation of the potential impact of unpublished studies on the results [19]. All p-values were calculated as two-sided, with a threshold of p

Five prespecified subgroups were analysed for the primary outcome: (1) non-small-cell lung cancer vs. other malignant neoplasms; (2) studies conducted in China vs. studies conducted outside China; (3) vitamin C dosage

Sensitivity analyses were conducted by successively excluding individual studies to evaluate the influence on the pooled effect size [20].

The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) [21] approach was applied to evaluate the overall certainty of the evidence supporting potential prolongation of survival following the administration of IVC. For each specific outcome assessed, the quality and certainty of the evidence were systematically judged using a scale that categorized them as “high”, “moderate”, “low”, or “very low”, thereby providing a comprehensive framework for understanding the reliability of the findings.

The findings derived from the extensive search, along with justifications for the exclusion of certain studies, are meticulously outlined in Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1. From an initial pool of 2637 records, a total of 8 eligible RCTs and cohort studies were identified, which collectively included 2722 adults diagnosed with malignant neoplasms [3, 4, 5, 7, 22, 23, 24, 25]. Details of the included studies are shown in Table 1 (Ref. [3, 4, 5, 7, 22, 23, 24, 25]). Notably, each study was published in reputable peer-reviewed journals, ensuring the credibility and reliability of findings. The median number of participants among the 8 studies was 85, with an interquartile range (IQR) of 47 to 370. Specifically, non-small cell lung cancer was the focus of two studies [4, 7], while several types of malignancy were examined in two other studies [22, 23]. Additionally, ovarian cancer [5], acute myeloid leukemia [24], triple-negative breast cancer [25], and colorectal cancer [3] were each the subject of one study. Geographically, 5 studies were conducted in China [3, 4, 7, 24, 25], and one each in the United States [5], the United Kingdom [22], and Turkey [23]. Seven studies [3, 4, 7, 22, 23, 24, 25] reported OS outcomes, and 5 [3, 4, 5, 7, 25] provided data on PFS outcomes, thereby contributing valuable insights into the effectiveness of various IVC treatments across different cancer types.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) flowchart outlining the search strategy and included studies.

| Study | Diagnosis | N (vitamin C/controls) | Study region | IVC | Control | IVC | Control | IVC dose and frequency | Concurrent therapy | Design |

| Median OS | Median OS | Median PFS | Median PFS | |||||||

| Cameron and Campbell 1991 [22] | Incurable cancer | 1826 (294/1532) | UK | 11.4 | 6 | NR | NR | 10 g/day for 10 days and orally thereafter (10 g/day) | Conventional anti-cancer treatment | RCT |

| Ma et al. 2014 [5] | Stage III and IV ovarian cancer | 22 (10/12) | USA | NR | NR | 25.5 | 16.75 | 75/100 g, twice weekly for 12 months | Paclitaxel and carboplatin | RCT |

| Günes-Bayir and Kiziltan 2015 [23] | Radiotherapy-resistant bone metastatic cancer | 39 (15/24) | Turkey | 10 | 2 | NR | NR | 2.5 g/day | Palliative radiotherapy | Retrospective cohort |

| Zhao et al. 2018 [24] | Elderly acute myeloid leukemia | 73 (39/34) | China | 15.3 | 9.3 | NR | NR | 50–80 mg/kg/day, days 0–9 | Decitabine, cytarabine and aclarubicin | RCT |

| Ou et al. 2020 [7] | Refractory advanced NSCLC | 97 (49/48) | China | 9.4 | 5.6 | 3 | 1.85 | 1 g/kg, three times per week for 25 treatments in total | Modulated electrohyperthermia and best supportive care | RCT |

| Ou et al. 2020 [25] | Advanced TNBC | 70 (35/35) | China | 27 | 18 | 7 | 4.5 | 1 g/kg/day, 25 treatments in total | Gemcitabine and carboplatin | Retrospective cohort |

| Wang et al. 2022 [3] | Metastatic colorectal cancer | 442 (221/221) | China | 20.7 | 19.7 | 8.6 | 8.3 | 1.5 g/kg/d for 3 hours from day 1 to day 3 for a maximum of 12 cycles | FOLFOX | RCT |

| Ou et al. 2023 [4] | NSCLC | 153 (72/81) | China | 49.2 | 25.6 | 39.5 | 8.5 | 1 g/kg/d, three times per week, 15 to 30 treatments in total | Standard anticancer treatments | Retrospective cohort |

IVC, intravenous vitamin C; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; NR, not reported; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; TNBC, triple-negative breast cancer; FOLFOX, folinic acid, fluorouracil, and oxaliplatin; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Fig. 2 is a visual representation of the potential biases in the studies analyzed here. Of the four RCTs that provided data on OS, three were deemed to have a minimal likelihood of bias throughout all assessed domains, indicating a high level of reliability in the findings [3, 7, 24]. Furthermore, each of the three cohort studies that contributed OS data had an impressive 9-star rating [4, 23, 25].

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Risk of bias assessment for primary outcome. (A) Traffic light plot of the RCTs. (B) Summary plot of the RCTs. (C) Assessment of the cohort studies.

A total of four RCTs encompassing 2438 participants and three cohort studies involving 262 participants collectively contributed data to the primary outcome of this analysis. Random-effects model analysis revealed that patients with malignant neoplasms and who were treated with IVC experienced a significantly longer median OS compared to those who did not receive this treatment, with a median survival ratio of 1.83 (95% CI: 1.40–2.40, p

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. The overall survival (A) and progression-free survival (B) of cancer patients who received intravenous vitamin C were compared to those who received no intravenous vitamin C. MSR, median survival ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Sensitivity analyses and funnel plots. (A) Sensitivity analysis for overall survival. (B) Sensitivity analysis for progression-free survival. (C) Egger test funnel plot for overall survival. (D) Egger test funnel plot for progression-free survival.

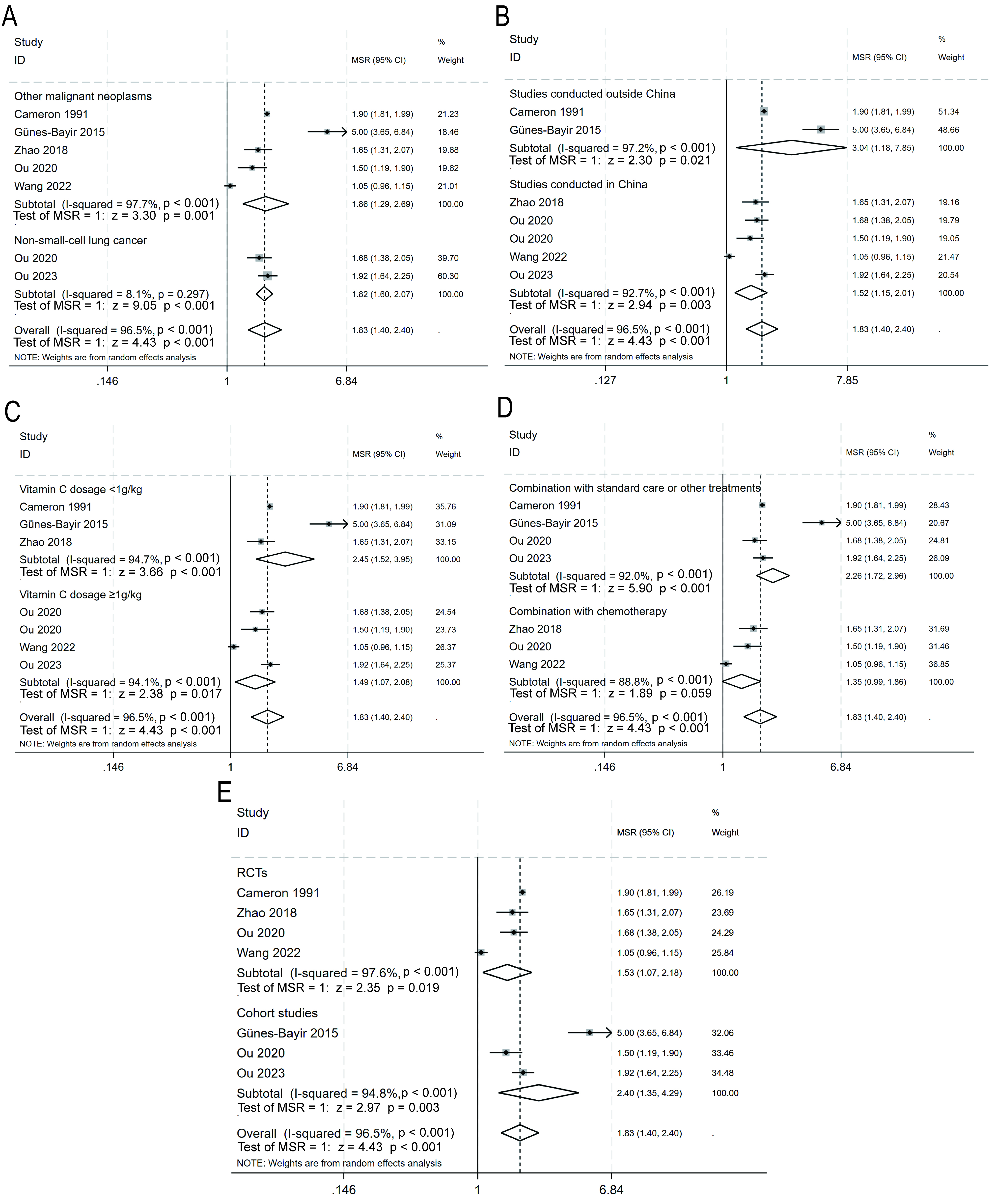

The primary outcome was also evaluated in five prespecified subgroups (Fig. 5). The pooled estimates were as follows: non-small-cell lung cancer (1.82, 95% CI: 1.60–2.07, p

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. Subgroup analyses for overall survival. (A) Non-small-cell lung cancer vs. other malignant neoplasms. (B) Studies conducted in China vs. studies conducted outside China. (C) Vitamin C dosage

Three RCTs with a total of 561 participants, and two cohort studies with a total of 223 participants contributed data for analysis of the secondary outcome (PFS). Analysis with a random-effects model revealed a trend for longer median PFS in patients with malignant neoplasms who received IVC, with a median survival ratio of 1.80 (95% CI: 0.95–3.41, p = 0.073; I2 = 98.4%; Fig. 3B). Furthermore, a sensitivity analysis revealed no significant sources of heterogeneity (Fig. 4B). The Egger regression test detected no trace of publication bias, with a p-value of 0.530 (Fig. 4D).

This systematic review and meta-analysis found that administration of IVC was associated with a significant improvement in the OS rate among patients diagnosed with a malignant neoplasm. Specifically, the findings revealed the median OS for patients receiving this treatment was 1.83-fold longer than those who did not receive IVC. Our analysis revealed not only a significant improvement in OS, but also a notable trend towards increased median PFS in patients who received IVC compared to those who did not.

This study offers several innovative contributions to the field of oncology. It represents the first quantitative meta-analysis on the administration of IVC for the treatment of patients with malignant tumors, thus filling a gap in the current literature and providing a reference for future research and clinical decision-making. The subgroup analysis for OS revealed differences in the therapeutic efficacy of IVC according to the dose and geographical location. While subgroup analysis showed a numerically higher median survival ratio in the

One of the main drawbacks of this research was the comparatively limited number of participants, which may affect the applicability of the findings to larger populations. The meta-analysis included eight studies with a total of 2722 participants. However, there were considerable differences in the sample size between different studies, which ranged from 22 to over 1000 participants. This heterogeneity in sample size may have contributed to the variability in observed treatment effects. Additionally, most studies were conducted in China [3, 4, 7, 24, 25], and differences in genetic background, environmental factors, and medical practice across regions may restrict the applicability of these findings across different populations. Another important limitation is the potential for confounding bias in observational studies [4, 23, 25], despite the use of various assessment tools to mitigate this impact. The current clinical studies on IVC lack unified standards, such as dosage, and the participants were often diverse, thereby limiting the interpretation and comparability of the study results. The subgroup analysis suggested that differences in study design (RCTs vs. cohort studies) were an important source of heterogeneity in the results of this study. Most studies reported short- and medium-term outcomes, with limited data on long-term survival. Additionally, the improvement in PFS with IVC did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.073), possibly due to insufficient sample size or differences in follow-up time. To address these limitations, future studies should focus on conducting larger-scale, multicenter RCTs that include diverse populations. Moreover, standardized dosing and follow-up protocols should be employed to enhance the reliability, interpretability, and generalizability of the results, as well as helping to determine the optimal dosage range for efficacy and long-term effects.

IVC acts through multifaceted mechanisms in antitumor therapy, including the induction of oxidative stress, co-factor activity, epigenetic regulation, hypoxia sensing, and immune modulation. The redox capacity of vitamin C catalyzes the generation of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) by iron or copper ions [26, 27, 28]. This results in the production of ROS and subsequent induction of DNA, protein, and lipid damage in cancer cells, leading to apoptosis. Cancer cells are characterized by high iron content, high metabolic rates, mitochondrial defects, and low catalase activity. Hence, they are more susceptible to oxidative stress and more vulnerable to vitamin C-induced oxidative damage than normal cells [29, 30]. Furthermore, when combined with chemotherapy or radiotherapy, vitamin C further increases oxidative stress and reduces antioxidant defenses, thereby significantly improving therapeutic efficacy [31, 32]. With regard to co-factor activity, vitamin C reduces ferric ions (Fe3+) to ferrous ions (Fe2+), thus modulating the function of iron-dependent proteins and influencing various metabolic activities such as the mitochondrial respiratory chain, collagen synthesis, and oxidative stress regulation [2]. Vitamin C also promotes collagen synthesis to stabilize the extracellular matrix, thereby inhibiting tumor invasion and metastasis [33, 34, 35]. It also regulates the degradation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1), thereby suppressing tumor growth and invasion in hypoxic environments [36, 37, 38]. In terms of epigenetic regulation, vitamin C modulates the function of TET enzymes to enhance DNA demethylation and reactivate the expression of tumor suppressor genes [39]. Moreover, vitamin C promotes the function of Jumonji C (JmjC) family histone demethylases to correct the aberrant epigenetic state of cancer cells and further disrupt tumor survival and proliferation [40]. Regarding immune modulation, vitamin C maintains high levels of immune cells and influences their differentiation, maturation, activation, and cytokine production through its antioxidant and co-factor activities [41]. Vitamin C also restores the epigenetic state of immune cells by modulating TET enzyme function [42]. Furthermore, vitamin C significantly enhances antitumor efficacy when combined with immune checkpoint inhibitors such as anti-programmed death-1 (anti-PD-1) and anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (anti-CTLA-4) [43, 44]. A clinical study suggested the biomarkers SERPINE1 and SERPINB7 were associated with the benefits of IVC treatment in non-small-cell lung cancer [4]. The postulated mechanism is that IVC downregulates the expression of SERPINE1 and SERPINB7, thereby inhibiting the proliferation and invasiveness of tumor cells and enhancing the efficacy of chemotherapy or radiotherapy to improve patient outcomes [4]. Future research should integrate preclinical and clinical studies to further elucidate the mechanism of IVC in cancer therapy.

IVC has emerged as a potential therapeutic agent for human malignancies. This study found that IVC extended the median OS of patients with malignant tumors by 1.83-fold. Additionally, a trend towards longer median PFS was also observed for patients receiving IVC. Nevertheless, it is important to note that considerable heterogeneity was found amongst the studies in terms of design, dosing regimens, and the diverse patient populations. Any conclusions should therefore be drawn with caution. Future studies should focus on large-scale, multicenter RCTs to further assess the effectiveness and safety of IVC.

Data will be made available on reasonable request.

JQ, MY, and BR designed the research study. JQ, MY, and SY performed the literature search, study selection, and data extraction. YW, SL, and BW resolved discrepancies during the study selection and data extraction process. JQ, MY, SY, JH, SW, YZ, and XW contributed to the risk of bias assessment and data validation. XT, XL, YR, and YL provided critical insights into the interpretation of the results. JQ and MY conducted the statistical analysis. BR supervised the project and secured funding. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 82474333, the National Key Research and Development Program of China, grant number 2022YFC2009601, and the Beijing Shijitan Hospital Capital Medical University Talent Cultivation Program during the 14th Five-Year Plan, grant number 2024LJRCRBQ.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/IJVNR37372.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.