1 Department of Nephrology, Affiliated Hospital of Shandong University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 250014 Jinan, Shandong, China

Abstract

Substantial experimental evidence has demonstrated that selenium, an essential micronutrient with pleiotropic physiological effects, also promotes dual antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects. Meanwhile, the epidemiological association between dietary selenium consumption and mortality risk in diabetic kidney disease (DKD) remains underexplored. This investigation demonstrated a significant association between selenium intake and all-cause mortality among adult populations with DKD.

This study analyzed data from 2183 individuals diagnosed with DKD, obtained from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) conducted between 2001 and 2014. The mortality rate was determined through linkage to the National Death Index until December 31, 2015. The hazard ratios (HRs) and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated using Cox proportional hazards regression models. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were generated to examine the association between survival probabilities and selenium intake.

A total of 1063 mortalities were recorded over an average follow-up period of 8 years. All-cause mortality decreased with higher selenium intake levels. Adjusted for demographic variables, dietary habits, lifestyle factors, glucose regulation, and significant comorbidities, higher selenium intake was associated with improved all-cause mortality among DKD patients (adjusted HR = 0.705, 95% CI: 0.551–0.901). A significant overall association was observed between selenium intake and all-cause mortality risk, as evidenced by restricted cubic spline (RCS) analysis (poverall < 0.001; pnonlinearity = 0.397).

Higher dietary selenium intake was significantly associated with lower risk of all-cause mortality after multivariable adjustment for confounders among individuals with DKD.

Keywords

- nutritional epidemiology

- diabetic kidney disease

- all-cause mortality

- selenium

- micronutrients

Diabetic kidney disease (DKD), formerly termed diabetic nephropathy, manifests as a diabetes-associated microvascular complication featuring elevated urinary protein excretion and reduced glomerular filtration rate [1]. DKD accounts for approximately 40% of diabetes-related renal complications in the U.S., imposing substantial public health burdens [2]. All-cause mortality rates in DKD patients are 30-fold higher than in diabetes patients without kidney impairment [3]. For the time being, strategies to delay DKD progression emphasize lifestyle modifications (e.g., diet, exercise) alongside pharmacotherapy to preserve renal function and glycemic control [4, 5].

Discovered in 1817, selenium was long considered toxic until 1957 when studies revealed its role in preventing liver necrosis in rats, establishing its biological significance. As an essential trace element, bioavailable selenium supports critical physiological functions including nervous, endocrine, cardiovascular, and immune system regulation, and is linked to immune-related disorders. Natural dietary sources include grains, seafood, vegetables, and meats [6, 7, 8].

While selenium is essential for health, research has shown that chronic selenium intake exceeding the Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) may induce toxic effects, including hepatotoxicity, peripheral neuropathy, and dermatological/nail abnormalities (e.g., alopecia, nail dystrophy) [9]. Based on evidence from Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT) trial and other studies, the European Food Safety Authority established a UL of 255 µg/day for adults, including pregnant and lactating women [10]. Selenium exhibits an extremely narrow therapeutic window, with only a 3- to 5-fold difference between nutritional benefits and toxic doses [11, 12]. This balance is particularly critical in diabetic kidney disease, where altered selenium metabolism may heighten toxicity risks.

Selenium regulates inflammation and immune responses through the

cyclooxygenase/lipoxygenase pathway, and serves as a key component of antioxidant

enzymes [13, 14, 15, 16]. Deficiency in selenium is bound up with diabetes, cardiovascular

diseases, autoimmune disorders, and cancer, particularly in developing countries

[17]. Its antioxidant properties are recognized in type 2 diabetes

pathophysiology and in mitigating oxidative stress linked to DKD [18, 19, 20, 21]. By

mimicking insulin action, reducing insulin resistance, and enhancing glucose

metabolism, selenium may offer beneficial effects for individuals with DKD [22].

Selenium exerts protective effects through selenoproteins, such as glutathione

peroxidases (GPx), which mitigate oxidative stress by neutralizing reactive

oxygen species (ROS) in renal tissues [23, 24, 25]. Aside from that, selenium

modulates nuclear factor-kappa B signaling, reducing pro-inflammatory cytokines

[e.g., interleukin-6 (IL-6); tumor necrosis factor-

However, there is limited evidence regarding the direct impact of selenium on patients with DKD who are subject to heightened oxidative stress and inflammation, factors that elevate their risk of mortality. This study aims to fill these knowledge gaps by examining the association between selenium intake and all-cause mortality risk in a nationally representative cohort of DKD adults in the United States.

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) database systematically compiles comprehensive health and nutrition data from a representative sample of the United States population. The database is updated biennially and is publicly accessible, enabling researchers to download the data for their studies. Participants’ biological samples, such as blood and urine, are meticulously collected and analyzed. Additionally, the database encompasses numerous questionnaires encompassing demographic and socioeconomic factors, dietary and health concerns, as well as physical examinations that involve anthropometric measurements and laboratory assessments.

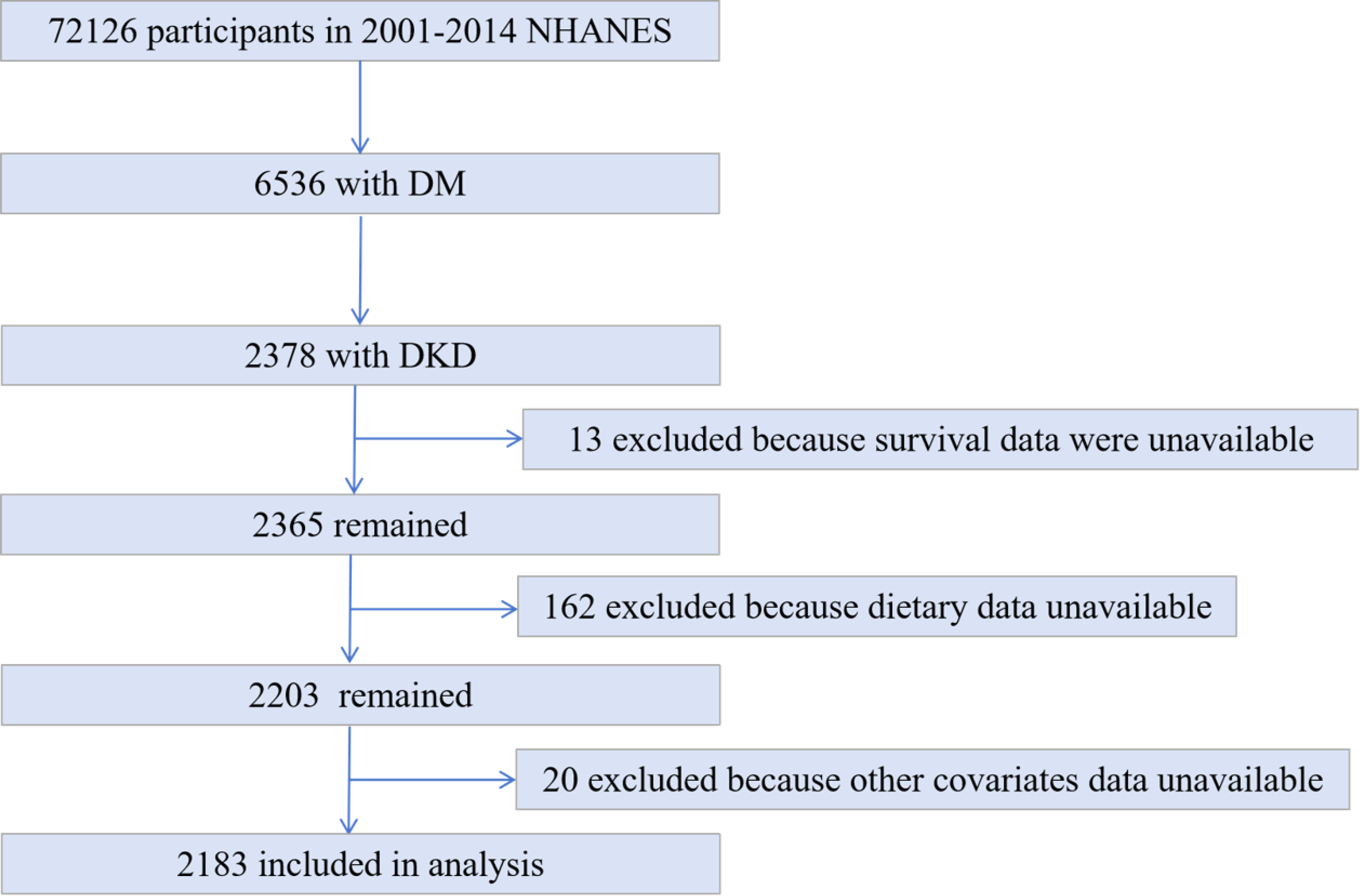

Data from NHANES 2001–2014 were utilized, which included information on

selenium intake. Initially, individuals diagnosed with diabetes mellitus at

baseline were included, creating a study group of 6536 participants. A

physician’s diagnosis, the use of insulin or oral medications to reduce blood

sugar, or the consumption of insulin supplements characterized diabetes mellitus.

Diagnosis was on the basis of a fasting blood sugar of

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of sample selection from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2001–2014. DM, diabetes mellitus; DKD, diabetic kidney disease.

Participants in the NHANES study underwent two 24-hour dietary recall interviews, the first conducted in person and the second via telephone 4–10 days later. Utilizing these two dietary recalls, the average selenium intake was calculated, with the analysis based on the Nutrients Database from the University of Texas Food Intake Analysis System [35]. Subsequently, the mean selenium intake was derived from the two recalls interviews.

Mortality status was ascertained using National Death Index records updated through December 31, 2015, with causes of death classified according to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision (ICD-10). codes. Cardiovascular disease deaths were identified by codes I00–I09, I11, I13, and I20–I51; cancer deaths were classified using codes C00–C97. The National Center for Health Statistics released the Public-Use Linked Mortality Files in 2015, which link to NHANES and span the years 1999–2014 [36]. These records provide detailed mortality status and underlying causes of death [37].

The surveys collected data on sociodemographic variables, smoking status,

dietary patterns, diabetes medications, lipid-lowering therapies, and the

presence of hypertension. Covariates were selected based on prior literature and

biological plausibility. Directed acyclic graphs guided adjustments for

confounders (e.g., age, HbA1c). Variance inflation factors were calculated to

assess multicollinearity; all variance inflation factors (VIFs) were

The analyses incorporated sample weights, and participants were stratified into

quartiles based on their selenium intake. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence

intervals were calculated using Cox proportional hazards regression. Models were

adjusted for covariates in three sequential steps: Model 1 (unadjusted), Model 2

(demographic and inflammatory factors), and Model 3 (additional adjustments for

glycemic control and renal function). Three models were utilized to compute HRs

and 95% confidence intervals. The first model was subject to no adjustment.

Model 2 was adjusted for sex, age, smoking status, family income-to-poverty

ratio, hemoglobin levels, serum albumin levels, serum uric acid levels, dietary phosphorus intake,

DII score, SII score, serum iron levels, and history of stroke. Model 3 was an

extension of Model 2, further adjusted to include HbA1c, hypertension,

hypoglycemic therapy, lipid-lowering therapy, and chronic kidney disease (CKD) stages defined by

estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR):

Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of 2183 participants with DKD

(mean age 65.9 years; 53.4% male), stratified by quartiles of dietary selenium

intake. The median selenium intake was 87.7 µg/day (interquartile range (IQR):

60.5–121.1 µg/day). Comparative analyses revealed significant differences

across quartiles: higher selenium intake groups exhibited elevated hemoglobin

(median Q4: 14.5 g/dL vs. Q1: 13.4 g/dL, p

| Characteristics | Total | Quartile 1 | Quartile 2 | Quartile 3 | Quartile 4 | p | |

| 60.5–87.6 µg/d | 87.7–121 µg/d | ||||||

| Patients, n | 2183 | 547 | 545 | 545 | 546 | ||

| Age, year (%) | 0.060 | ||||||

| 5.1 | 2.3 | 6.0 | 4.7 | 7.0 | |||

| 40–60 | 26.1 | 23.4 | 28.0 | 25.8 | 27.0 | ||

| 68.8 | 74.3 | 66.0 | 69.5 | 66.0 | |||

| Male sex (%) | 53.4 | 52.8 | 57.1 | 54.0 | 49.9 | 0.270 | |

| Race (%) | 0.690 | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 40.1 | 43.6 | 38.8 | 40.4 | 38.0 | ||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 28.1 | 26.8 | 27.4 | 26.8 | 31.0 | ||

| Mexican American | 18.5 | 17.2 | 19.8 | 17.3 | 19.5 | ||

| Other | 13.3 | 12.4 | 14.0 | 15.5 | 11.5 | ||

| Family income-to-poverty ratio (%) | 0.960 | ||||||

| 22.9 | 21.7 | 22.3 | 22.6 | 24.8 | |||

| 1–3 | 52.8 | 54.4 | 52.5 | 52.3 | 52.1 | ||

| 24.3 | 23.9 | 25.2 | 25.1 | 23.1 | |||

| Smoking states (%) | 0.340 | ||||||

| Never smoker | 45.0 | 48.8 | 43.9 | 42.7 | 44.7 | ||

| Former smoker | 38.1 | 36.0 | 41.7 | 39.2 | 35.6 | ||

| Now smoker | 16.9 | 15.2 | 14.4 | 18.1 | 19.7 | ||

| HbA1c, % (%) | 0.002 | ||||||

| 48.5 | 58.1 | 47.6 | 46.4 | 42.6 | |||

| 51.5 | 41.9 | 52.4 | 53.6 | 57.4 | |||

| Stroke (%) | 12.4 | 14.8 | 12.0 | 13.5 | 9.6 | 0.240 | |

| Hypertension (%) | 80.9 | 80.2 | 84.4 | 82.8 | 76.6 | 0.070 | |

| HGB, g/dL | 13.9 (12.6, 15.0) | 13.4 (12.3, 14.7) | 13.8 (12.5, 14.9) | 12.7, 15.0 | 14.5 (13.1, 15.6) | ||

| ALB, g/dL | 4.1 (3.9, 4.3) | 4.1 (3.9, 4.3) | 4.1 (3.9, 4.3) | 4.1 (3.9, 4.3) | 4.2 (3.9, 4.4) | 0.050 | |

| UA, mg/dL | 6.1 (5.0, 7.3) | 6.2 (5.2, 7.3) | 6.2 (5.2, 7.4) | 6.0 (5.0, 7.2) | 5.9 (4.9, 7.1) | 0.150 | |

| Iron, µg/dL | 74.0 (57.0, 96.0) | 68.0 (53.0, 91.0) | 75.0 (57.0, 99.0) | 74.0 (56.0, 93.0) | 79.0 (62.0, 101.0) | 0.005 | |

| Phosphorus intake, mg/day | 1082.0 (795.0, 1503.0) | 651.0 (484.0, 868.0) | 929.0 (769.0, 1119.0) | 1204.0 (998.0, 1496.0) | 1661.0 (1360.0, 2102.0) | ||

| Selenium intake, µ/d | 89.6 (61.5, 124.6) | 45.2 (33.6, 55.0) | 73.4 (67.5, 80.1) | 104.3 (96.3, 112.6) | 154.1 (134.2, 184.5) | ||

| DII | 2.2 (0.7, 3.2) | 3.4 (2.3, 4.0) | 2.7 (1.5, 3.4) | 1.7 (0.6, 2.8) | 0.8 (–0.5, 2.0) | ||

| SII | 536.4 (378.3, 788.8) | 561.0 (367.7, 825.9) | 544.2 (396.1, 792.0) | 542.8 (382.5, 805.2) | 504.7 (352.4, 728.5) | 0.120 | |

| Hypoglycemic treatment (%) | 65.1 | 65.7 | 67.6 | 65.0 | 62.2 | 0.540 | |

| Lipid-lowering therapy (%) | 90.1 | 88.4 | 93.9 | 89.9 | 88.3 | 0.050 | |

| Mortality (%) | 47.4 | 54.1 | 51.2 | 45.2 | 39.9 | ||

HGB, hemoglobin; ALB, albumin; UA, uric acid; DII, Dietary Inflammatory Index; SII, Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index.

The continuous variables in this study non-normally distributed and are thusreported as median (interquartile range [IQR]). Categorical variables are presented as %.

Table 2 presents the all-cause mortality HRs for patients with DKD stratified by

quartiles of selenium intake. In Model 1, which is unadjusted, the crude HRs

(with 95% CIs) for mortality were observed across selenium intake categories of

| Exposure | Quartiles of dietary selenium intake (µg/day) | p for trend | |||

| Range | Q1: |

Q2: 60.5–87.6 µg/d | Q3: 87.7–121 µg/d | Q4: | |

| No. death/total | 299/547 | 283/545 | 255/545 | 226/546 | |

| Model 1 | 1 (reference) | 0.817 (0.669, 0.998) | 0.741 (0.611, 0.900) | 0.610 (0.496, 0.749) | |

| Model 2 | 1 (reference) | 0.810 (0.670, 0.979) | 0.786 (0.628, 0.985) | 0.714 (0.560, 0.909) | 0.015 |

| Model 3 | 1 (reference) | 0.813 (0.669, 0.987) | 0.789 (0.629, 0.989) | 0.705 (0.551, 0.901) | 0.021 |

Unless stated differently, data are presented as hazard ratio (HR) (95% CI).

Model 1: unadjusted model.

Model 2: adjusted for age (

Model 3: Model 2 adjusted for additional variables: HbA1c (

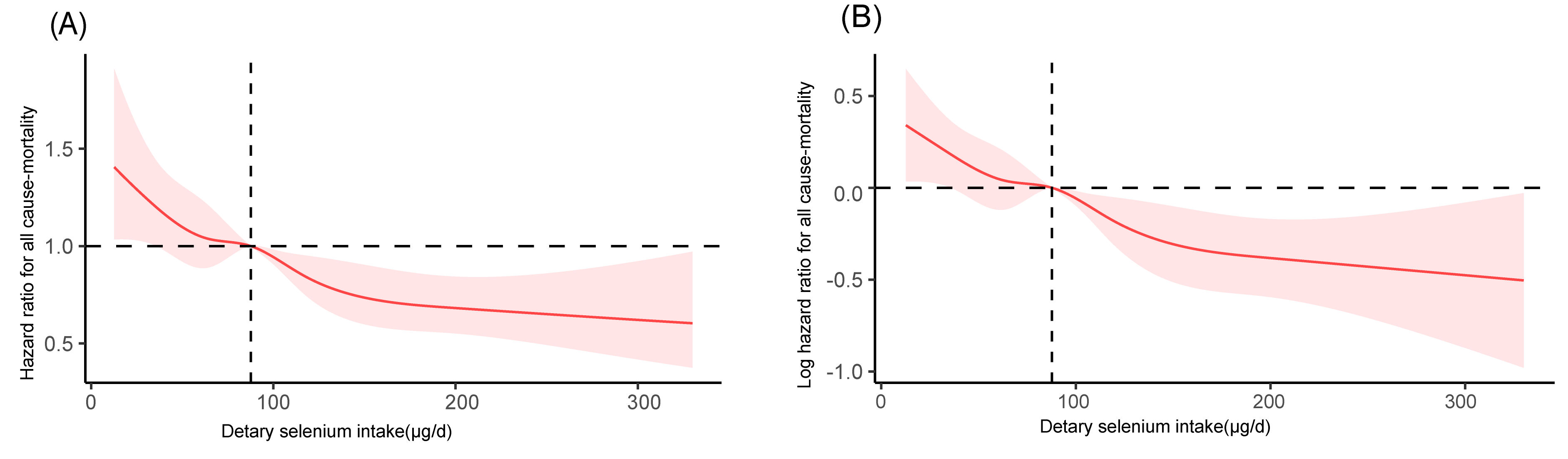

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Restricted cubic spline analysis of the association between

dietary selenium intake and all-cause mortality in DKD patients (NHANES

2001–2014). (A) Untransformed hazard ratio (HR) with a reference line at HR =

1. (B) Log-transformed hazard ratio (logHR) with a reference line at logHR = 0

(equivalent to HR = 1). Both panels were adjusted for age, sex, family

income-to-poverty ratio, smoking status, hemoglobin, albumin, uric acid, dietary

phosphorus intake, Dietary Inflammatory Index (DII), Systemic Immune-Inflammation

Index (SII), serum iron, stroke history, HbA1c, hypertension, hypoglycemic

treatment, lipid-lowering therapy, and CKD stages. A median selenium intake of

87.7 µg/day was used as the reference. Shaded bands represent 95% confidence

intervals. A significant overall association was observed (poverall

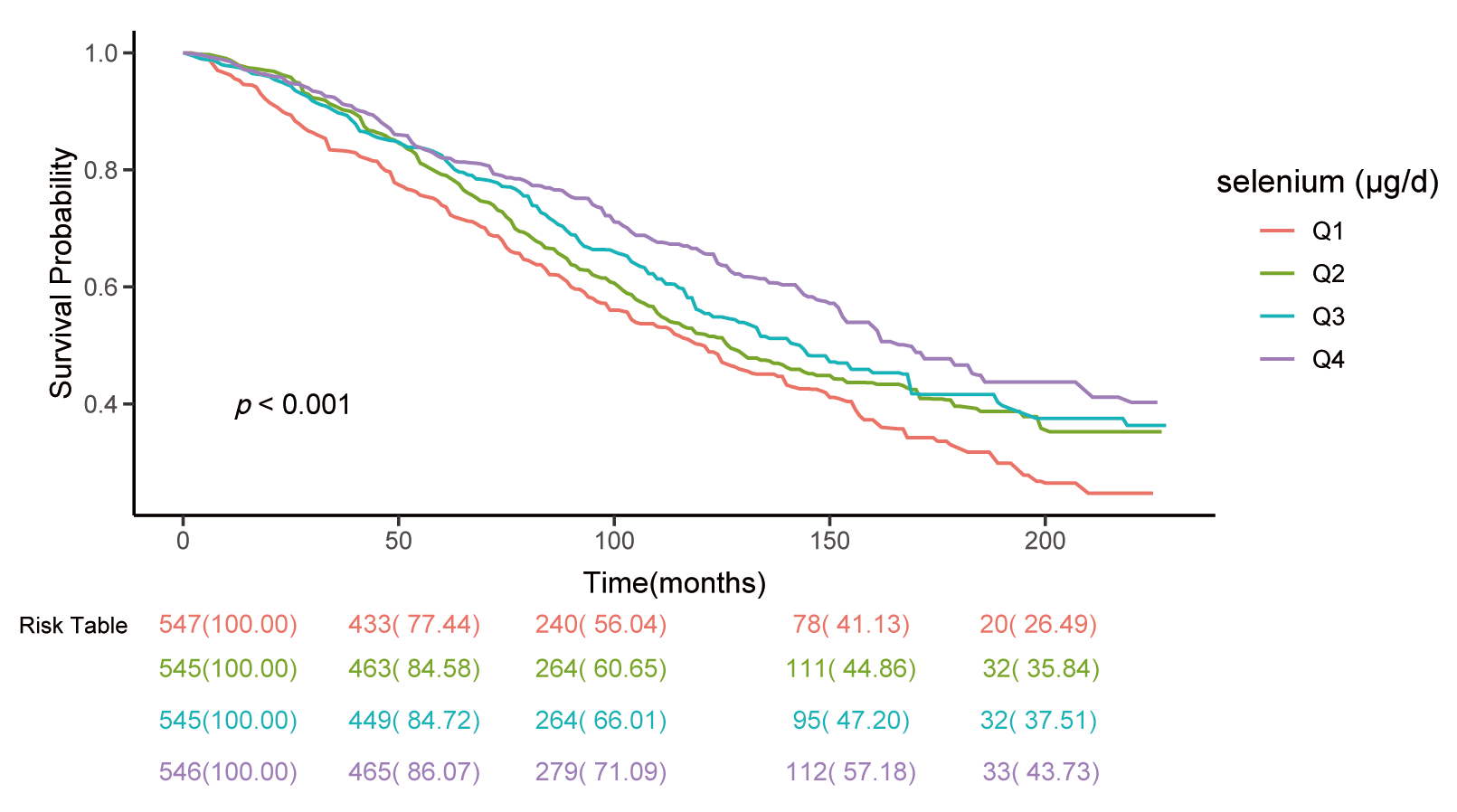

The Kaplan-Meier survival analysis in Fig. 3 demonstrates the relationship

between dietary selenium intake and all-cause mortality. The risk table outlines

the number of participants at risk and cumulative survival probabilities (in

parentheses) across follow-up periods for each quartile (Q1: lowest, Q4: highest

selenium intake). Survival curves for the highest intake group (Q4) exhibit

higher survival probabilities compared with lower intake groups (Q1–Q3),

indicating improved long-term survival. Log-rank test revealed significant

differences across quartiles (p

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for all-cause mortality by

quartiles of dietary selenium intake. Among individuals with DKD, those with a

daily selenium intake of less than 60.4 µg/d exhibit the lowest cumulative

survival probabilities, whereas individuals consuming more than 121.0 µg/d

demonstrated significantly higher. log-rank test, p

Subgroup analyses revealed a consistent association between selenium intake and

all-cause mortality when stratified by age

| Characteristic | Dietary selenium intake | p for trend | p interaction | ||||

| Quartile 1 | Quartile 2 | Quartile 3 | Quartile 4 | ||||

| Age, years | 0.250 | ||||||

| ref | 0.349 (0.113, 1.078) | 0.455 (0.148, 1.399) | 0.459 (0.126, 1.666) | 0.609 | |||

| 40–60 (n = 520) | ref | 0.529 (0.338, 0.826) | 0.668 (0.393, 1.133) | 0.404 (0.192, 0.853) | 0.059 | ||

| ref | 0.918 (0.709, 1.189) | 0.751 (0.570, 0.989) | 0.688 (0.487, 0.973) | 0.021 | |||

| Sex | 0.532 | ||||||

| Male (n = 1030) | ref | 0.901 (0.700, 1.160) | 0.710 (0.503, 1.004) | 0.591 (0.393, 0.889) | 0.009 | ||

| Female (n = 1153) | ref | 0.716 (0.543, 0.945) | 0.742 (0.543, 1.014) | 0.619 (0.437, 0.876) | 0.014 | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.898 | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White (n = 940) | ref | 0.847 (0.625, 1.147) | 0.799 (0.563, 1.134) | 0.666 (0.408, 1.086) | 0.109 | ||

| Non-Hispanic Black (n = 550) | ref | 0.686 (0.481, 0.977) | 0.649 (0.431, 0.977) | 0.444 (0.276, 0.715) | 0.002 | ||

| Mexican American (n = 398) | ref | 0.929 (0.622, 1.387) | 0.682 (0.346, 1.344) | 0.737 (0.389, 1.396) | 0.269 | ||

| Other (n = 295) | ref | 0.769 (0.390, 1.514) | 0.758 (0.313, 1.833) | 0.905 (0.377, 2.174) | 0.733 | ||

| HbA1c (%) | 0.415 | ||||||

| ref | 0.797 (0.611, 1.040) | 0.829 (0.645, 1.066) | 0.588 (0.418, 0.827) | 0.004 | |||

| ref | 0.790 (0.553, 1.129) | 0.640 (0.430, 0.952) | 0.635 (0.403, 1.000) | 0.037 | |||

| eGFR-EPI, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 0.302 | ||||||

| ref | 0.763 (0.505, 1.151) | 0.930 (0.623, 1.387) | 0.731 (0.451, 1.184) | 0.419 | |||

| ref | 0.926 (0.756, 1.135) | 0.661 (0.503, 0.869) | 0.629 (0.443, 0.893) | 0.001 | |||

The data are presented as HRs with 95% CIs, adjusted for various covariates

including age (

This study represents the first investigation into the relationship between dietary selenium intake and all-cause mortality among individuals with DKD. A significant dose-response relationship was identified between selenium intake and all-cause mortality. Importantly, this association remained independent of established risk factors, including diet and lifestyle, as well as interventions aimed at reducing blood glucose and lipid levels. Stratified analyses confirmed the robustness of our findings.

Our study identified a dose-dependent inverse association between dietary selenium intake and all-cause mortality in patients with DKD, a finding that aligns with the Invecchiare in Chianti (InCHIANTI) Study, where individuals in the lowest selenium quartile exhibited a 56% higher mortality risk compared with those in the highest quartile [40]. However, our results contrast with a meta-analysis showing no significant mortality reduction with selenium supplementation in mixed populations [41], and diverge from a cohort of older adults reporting a U-shaped relationship between plasma selenium and mortality [42]. In contrast to prior studies in general or aging populations, our analysis exclusively targeted DKD patients—a high risk group characterized by increased oxidative stress and inflammation, where selenium’s antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects may exert stronger protective effects. While previous trials evaluated supplemental selenium (often in isolation), our study assessed dietary intake, reflecting real-world nutrient interactions and bioavailability.

Dietary selenium primarily exists in organic forms, such as selenomethionine, which exhibit significantly higher bioavailability than inorganic selenium compounds. A study has demonstrated that the absorption efficiency of organic selenium exceeds 80% [43]. The bioavailability of selenium from dietary supplements, when co-ingested with food matrices, was determined to be within the range of 19.31%–66.10% [44]. Organic selenium enhances immunity through GPx synthesis, while excessive inorganic supplementation may inhibit immune function [45]. Prioritizing selenium-rich foods provides synergistic cofactors [43, 46]. Public health strategies should emphasize ‘dietary prioritization, targeted supplementation, and risk control’, tailored to regional and population-specific characteristics [47].

The protective role of dietary selenium in reducing all-cause mortality among

DKD patients may be mediated through multifaceted mechanisms targeting insulin

resistance, oxidative stress, and inflammation-key drivers of DKD progression

[48, 49, 50, 51]. (1) Improvement of Insulin Sensitivity and Metabolic

Regulation. GPx and thioredoxin reductases are selenium-dependent enzymes; thus,

selenium deficiency induces oxidative damage to

In hierarchical analysis, Non-Hispanic Black individuals in the highest selenium intake quartile (Q4) revealed a strikingly lower HR (HR = 0.444, 95% CI: 0.276–0.715) in comparison with other racial/ethnic groups. This pronounced protective association may stem from a combination of genetic and dietary factors unique to this population. The metabolism of selenium is heavily influenced by genetic polymorphisms in selenoprotein-coding genes, such as those encoding selenoprotein P (SEPP1). For instance, SEPP1 is a key transporter of selenium in plasma, and functional variants in this gene (e.g., rs7579, rs3877899) have been demonstrated to alter selenium distribution and bioavailability [61]. Zhou et al. [62] reported that individuals with specific SEPP1 variants experienced differential lipid profile changes in response to selenium intake, suggesting gene-nutrient interactions may modulate health outcomes. Dietary patterns also play a crucial role in this process. Coastal or Southern U.S. populations, including a multitude of African American communities, traditionally consume higher amounts of selenium-rich foods such as fish, shellfish, and certain nuts. This dietary habit could maintain more stable selenium stores, optimizing its biological functions (e.g., glutathione peroxidase activity). Additionally, cultural food preparation methods (e.g., stewing or slow cooking) might preserve selenium bioavailability compared with processing techniques that degrade micronutrients.

Our findings suggest that optimizing selenium intake in DKD patients could reduce all-cause mortality risk. While current guidelines emphasize glycemic control and renoprotective agents, selenium supplementation may emerge as an adjunctive strategy. Future randomized trials should validate causality and define optimal dosing thresholds. From a clinical perspective, assessing selenium status (e.g., serum selenium levels) could help identify high-risk patients who may benefit from targeted interventions. Nevertheless, caution is warranted given potential toxicity at supranutritional intake levels.

In spite of the aforementioned contributions, the study’s limitations involve numerous aspects, which are mirrored in its observational design, which precludes causal inference, and limited data on DKD severity, even after adjusting for diabetes medications and HbA1c levels. Data on diabetes duration in NHANES were insufficient to adjust for disease chronicity, a factor that may influence mortality outcomes. The findings are specific to U.S. adults enduring diabetes, thereby limiting generalizability. As suggested by the absence of genetic analysis on selenium metabolism, future research should explore diet-gene interactions affecting mortality. Moreover, the limited statistical power in subgroup analyses warrants cautious interpretation.

This study identified an association between increased dietary selenium intake and decreased mortality rates among patients with DKD. The findings suggest that selenium intake may offer mortality benefits for individuals with DKD.

The study includes the original contributions, which are detailed in the article . For additional information, inquiries may be directed to the corresponding author.

XW: Conducted data analysis and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. DW and SS: Contributed to study conceptualization, research design, and critical revision of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Ethical approval was not required for this study, as it analyzed de-identified, publicly available data from the NHANES. NHANES protocols were approved by the National Center for Health Statistics Ethics Review Board, and all participants provided written informed consent prior to data collection. The study was carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Not applicable.

This study was supported by Qilu Traditional Chinese Medicine Advantage Specialist Cluster Project and Shandong Traditional Chinese Medicine Technology Project (Grant Numbers: Z-2023062T, Q-2023014).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.