1 Department of Preventive & Social Medicine, University of Otago, 9016 Dunedin, New Zealand

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Clinical and epidemiological evidence supports sodium reduction as an effective strategy to lower blood pressure and reduce the risk of stroke, cardiovascular disease, and overall mortality. High sodium (salt) intake is a well-established contributor to elevated blood pressure and adverse cardiovascular outcomes. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that adults should consume less than 5 g of table salt per day; however, the global average intake is estimated at around 10.78 g/day. The primary sources of dietary sodium vary by region: in high-income countries, the majority of salt intake comes from processed foods and meals prepared outside the home, while in many low-and middle-income countries, sodium is mainly added during home cooking or comes from condiments such as soy sauce and fish sauce. This review discusses the effects of high dietary sodium on blood pressure and vascular health, along with global consumption trends, regional disparities, and key nutritional sources. In addition to reducing sodium, adopting a salt-sensitive, whole-diet approach, such as increasing fruit and vegetable intake to boost potassium, can further protect cardiovascular health. Potassium-enriched, low-sodium salt substitutes are increasingly used in food production. Emerging strategies, including flavor enhancers, bitter blockers, spatial salt distribution, and microencapsulation, also help enhance saltiness perception while lowering sodium content. The review also summarizes national guidelines and those by the WHO, highlights selected country strategies, and calls for coordinated global and national efforts to reduce sodium intake and improve cardiovascular health worldwide.

Keywords

- sodium

- salt reduction

- cardiovascular disease

Salt (sodium chloride) has played a crucial role in human history for thousands of years, dating back to early humans extracting it from natural brine springs [1]. It has served as an essential ingredient for both food preservation and flavor enhancement due to its distinctive salty taste. Over the centuries, salt has become a fundamental component in global cuisines, valued for its dual role in preserving food and enhancing flavor. Today, around 90% of sodium intake comes from sodium chloride (NaCl), primarily consumed through salt added during the manufacture of processed foods, in cooking, at the table, or in salty sauces and condiments [2].

Sodium is an essential nutrient and is required for a number of functions, including regulation of fluid balance, as well as facilitating neuronal activity, and muscular contraction. In traditional and indigenous societies, sufficient sodium is obtained through that inherent in food. It has been estimated that the human body requires just a minimum of sodium—approximately 0.5 g daily—for basic activities, and cardiovascular health [3]. Some population groups have been shown to consume as little as 23 mg of sodium per day with no adverse effects [4]. However, due to the large amount of added salt in the modern diet, the current global average sodium consumption is roughly 4 g daily (equal to about 11 g of salt) [5], exceeding the World Health Organization’s (WHO) guideline of less than 2 g (5 g of salt) per day by more than twofold [6]. The excessive consumption of sodium causes considerable risks to health, especially to cardiovascular health, making salt reduction a priority public health concern globally.

Excessive sodium intake is a well-established risk factor for elevated blood pressure, which has been associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD), including ischemic and hypertensive heart disease and stroke [5]. CVD is the leading cause of global mortality, resulting in approximately 17.9 million deaths in 2019, with heart attacks and strokes constituting 85% of these deaths [7]. Estimates from the Global Burden of Disease Study indicate an almost double rise in CVD prevalence, rising from 271 million cases in 1990 to 523 million in 2019 [8] and is anticipated to rise by 90.0% between 2025 and 2050, with projected cardiovascular-related deaths reaching approximately 35.6 million by 2050 [9]. Despite substantial advancements in prevention and treatment, CVD continues to be the top cause of mortality and morbidity in both high- and low-income regions, contributing heavily to the global disease burden. Additionally, it is estimated that 1.9 million deaths worldwide each year are directly associated with high sodium intake [10], demonstrating the necessity of addressing this modifiable risk factor. Given the strong link between high sodium intake and elevated CVD risk, effective sodium reduction strategies are critical for global CVD prevention efforts [8].

Since salt reduction is a well-recognized cost-effective intervention [11], WHO and the United Nations identified dietary salt reduction as one of nine key global strategies to decrease premature mortality from non-communicable diseases (NCDs), including CVD. Member states of WHO have committed to reducing global population sodium intake by 30% by 2025 in order to control blood pressure, and reduce mortality and morbidity from NCDs [12]. In addition to sodium reduction, the efforts of using lower-sodium salt substitutes (LSSS) , and a whole-diet approach that includes increased consumption of fruits and vegetables to boost potassium intake has been highlighted as a complementary strategy to further enhance cardiovascular health [13]. Higher dietary potassium intake can mitigate the adverse effects of sodium on blood pressure and vascular health, providing an additional layer of protection against CVD [14, 15].

This review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the role of sodium (salt) reduction in the prevention and management of CVD. While the health risks of excessive sodium intake are widely known, major gaps remain in the understanding of regional disparities in salt consumption patterns and the varying success of national salt reduction policies. It explores global sodium intake, summarises epidemiological evidence on the relationship between sodium and potassium consumption, blood pressure, and CVD, and describes international efforts targeting sodium reduction as a preventive strategy. Additionally, the review outlines the effectiveness and challenges of these efforts and discusses relevant public health policies, aiming to enhance the discourse on implemented prevention and management strategies for CVD worldwide.

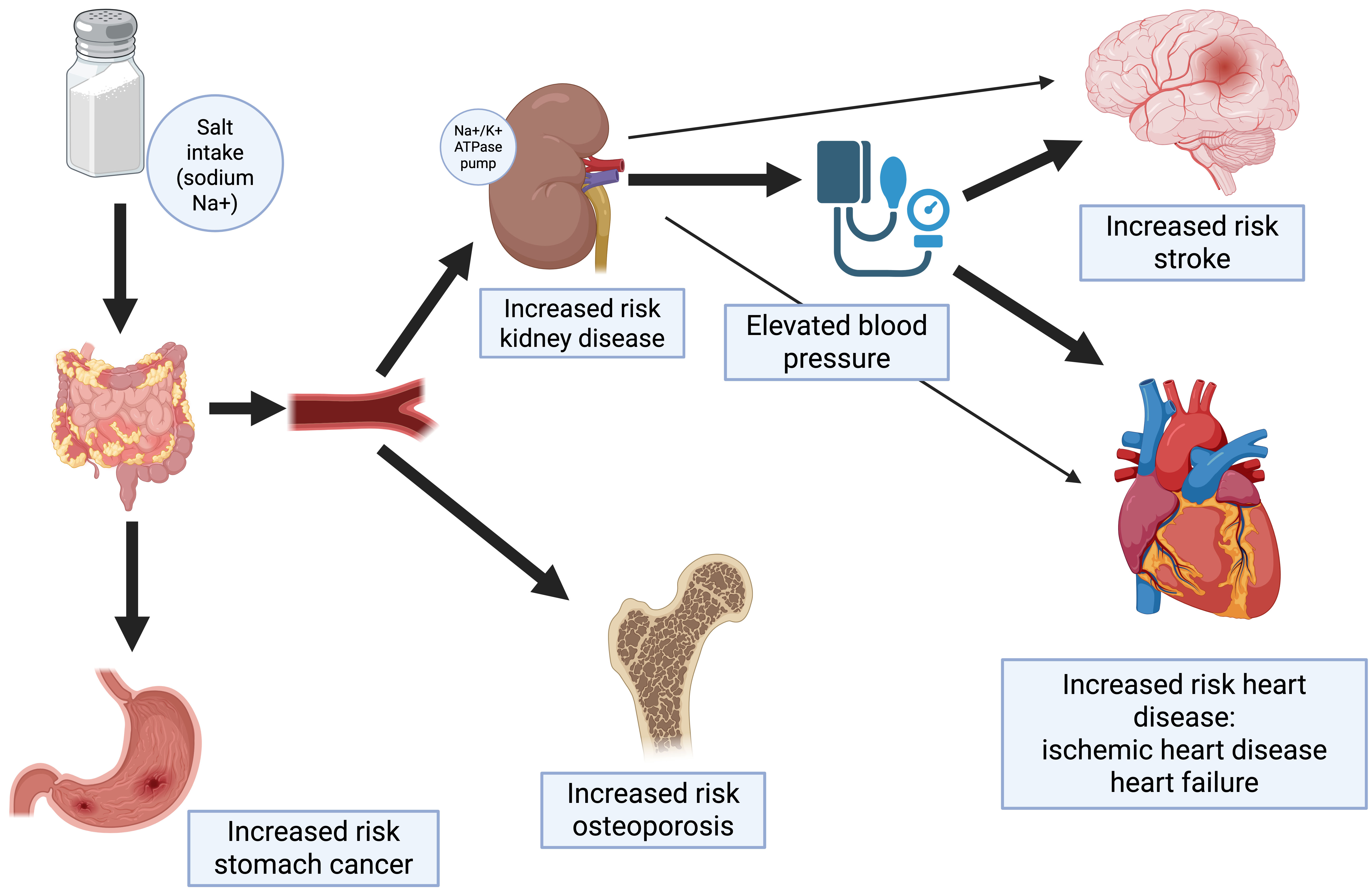

The adverse health effects of a diet high in sodium are summarized in Fig. 1. These include increased risk of CVD (including elevated blood pressure, stroke, and heart disease), kidney disease, stomach cancer, and osteoporosis. Key pathways illustrated in Fig. 1 include elevated blood pressure and altered sodium handling via the Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase pump in the kidney, leading to fluid retention and elevated blood pressure. These factors lead to increased risk of kidney damage. Elevated blood pressure is strongly associated with increased risk of heart disease and stroke. While elevated blood pressure is a well-known intermediary, sodium exerts harmful effects beyond blood pressure regulation. Excess sodium promotes endothelial dysfunction, increases vascular stiffness, and induces left ventricular hypertrophy and adverse cardiac remodeling—processes that collectively contribute to heart failure and atherosclerosis progression [16, 17]. Sodium-related kidney damage is mediated by impaired renal sodium handling, increased glomerular pressure, and activation of the sympathetic nervous system and the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) [18, 19]. Importantly, a recent dose–response meta-analysis based on 24-hour urinary sodium excretion confirmed a linear relationship between sodium intake and hypertension risk, with no evidence of a safe lower threshold, highlighting the pitfalls of biased estimation methods such as spot urine [20]. Sodium-induced gastrointestinal effects also elevate the risks of stomach cancer and osteoporosis. Here we focus on cardiovascular disease outcomes and effects on the kidney.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Adverse effects of high sodium (salt) intake.

High sodium intake is associated with elevated blood pressure, hypertension, and adverse effects on the cardiovascular system through multiple physiological mechanisms, thereby increasing CVD risk [21]. Key pathways include blood pressure elevation, endothelial dysfunction, sympathetic nervous system activation, oxidative stress, and endocrine system alterations. Increased sodium levels raise blood volume, elevating blood pressure—a primary risk factor for CVD. Endothelial dysfunction from high sodium intake impairs vasodilators like nitric oxide, leading to vascular stiffness and heightened resistance [22].

Sodium intake also stimulates the sympathetic nervous system, further elevating blood pressure and heart rate, which adds stress to the cardiovascular system. Additionally, oxidative stress and inflammatory responses contribute to cellular damage and vascular disease progression. Changes in RAAS, along with genetic factors, immune activation, and gut microbiome alterations, are implicated in salt-sensitive hypertension—a condition in which an individual’s blood pressure fluctuates markedly in response to variations in sodium intake—underscoring the complex, detrimental effects of excessive sodium on cardiovascular health [22, 23].

The kidney is essential in regulating sodium and potassium balance through the interplay of transport proteins and hormonal mechanisms. In the distal tubule and collecting duct, sodium reabsorption and potassium excretion are primarily mediated by the sodium-potassium ATPase (Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase) located on the basolateral membrane of tubular cells. This pump actively transports sodium from the cell into the bloodstream while importing potassium into the cell, establishing an electrochemical gradient that facilitates further sodium reabsorption from the tubular lumen and potassium secretion into the urine [24]. Aldosterone, a key regulatory hormone, amplifies this process by upregulating the activity of Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase and sodium channels, thereby ensuring the maintenance of electrolyte homeostasis, blood pressure, and extracellular fluid volume [25].

Excessive sodium intake promotes increased sodium reabsorption in the kidney, resulting in fluid retention, elevated blood pressure, and a suppression of aldosterone secretion, which reduces potassium excretion and risks hyperkalemia [26]. In contrast, reducing sodium intake while increasing dietary potassium stimulates aldosterone release, enhancing sodium excretion and potassium secretion in the distal tubule and collecting duct [27]. These adjustments effectively lower blood pressure, restore the sodium-potassium balance, and mitigate the adverse vascular effects associated with high sodium intake [25].

Evidence from a range of study designs in diverse global populations demonstrates a consistent positive association between sodium intake and blood pressure. There is strong evidence of an association between elevated blood pressure and increased risk of cardiovascular diseases, and blood pressure lowering is a cornerstone of CVD prevention globally. Further, there are a small number of well-conducted trials of sodium reduction that demonstrate a direct association between dietary sodium reduction and reduction in CVD outcomes, and meta-analyses of observational studies show an association between high sodium intake and increased risk of CVD including stroke [21].

Cross-sectional studies of populations with varying sodium intakes strongly link sodium intake to blood pressure and cardiovascular health. Early observational studies, such as the Intersalt study (1988), examined the relationship between sodium intake and blood pressure over ten thousand men and women across 52 different communities in 32 countries worldwide. Populations with low sodium intake, displayed much lower blood pressure levels and lower hypertension rates compared to communities with higher sodium consumption [28]. The Intersalt Study found that populations with lower sodium intake generally had lower average blood pressure and lower prevalence of hypertension than those with higher sodium consumption. In addition, in four populations with extremely low sodium excretion, such as the Yanomami people in the Amazon, blood pressure levels were low, and there was no evidence of blood pressure increasing with age [29]. Subsequently, a large number of clinical trials have shown a dose-response relationship between sodium intake levels and both systolic and diastolic blood pressure across the full range of sodium consumption. The effect on blood pressure lowering with dietary sodium reduction is particularly pronounced in participants with higher baseline levels of blood pressure [30], leading to the suggestion that some individuals and racial groups are more ‘salt-sensitive’ than others. Blood pressure lowering is also maximised when sodium is lowered alongside improvements in diet quality overall.

Beyond sodium reduction alone, comprehensive dietary patterns such as the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet have demonstrated significant efficacy in lowering blood pressure. The DASH diet emphasizes a high intake of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, low-fat dairy products, lean protein, and nuts, while reducing consumption of red meats, added sugars, and saturated fat. It is naturally rich in potassium, calcium, and magnesium—nutrients known to support vascular health—and limits sodium intake to enhance its antihypertensive effect [31].

The DASH-Sodium trial showed the blood pressure-lowering effect of the DASH diet, characterized by high intake of potassium-rich fruits and vegetables, low-fat dairy products, and reduced saturated fat. The DASH diet is designed to achieve a target potassium intake of approximately 4.7 g/day, primarily through these nutrient-dense food sources. This trial also evaluated three sodium intake levels, exemplified by high (3.45 g/day), intermediate (2.3 mg/day), and low (1.15 mg/day) for a 2100 kcal diet, with adjustments made for other energy intake levels [32]. The findings confirmed a dose-response relationship between sodium intake and blood pressure reduction, with the most significant reductions observed when the DASH diet was paired with a sodium intake level below 2.3 mg/day [33]. The DASH diet does not explicitly examine the impact of individual nutrients on blood pressure; however, with the effect reported mostly in adults with hypertension, a systematic review and meta-analysis indicated that higher potassium intake considerably lowered systolic blood pressure by 3.49 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure by 1.96 mmHg. Additionally, systolic blood pressure was reduced by 7.16 mmHg with potassium intakes ranging from 90 to 120 mmol/day, with no clear dose-response association [13].

In 2012, WHO provided evidence from various randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and cohort studies showing that reducing sodium intake can lower both systolic and diastolic blood pressure and reduce the risk of CVD, with more pronounced effects observed in individuals with hypertension and those with higher sodium intake. A meta-analysis indicated that as sodium intake decreased, systolic blood pressure dropped by 3.39 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure by 1.54 mmHg, demonstrating a clear dose-response relationship. Additionally, sodium reduction interventions targeting an intake of less than 2 g/day were associated with significant improvements in blood pressure [6]. Similarly, a Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis showed that modest salt reduction for 4 weeks or more lowered blood pressure in hypertensive and normotensive individuals regardless of sex or ethnicity, with additional benefits of reduced stroke and coronary artery disease risk in adults [34].

A systematic review and meta-analysis analyzed 133 randomized trials with 12,197 participants, confirmed a dose-response relationship between sodium reduction and blood pressure reduction. On average, reducing sodium intake lowered systolic blood pressure by 4.26 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure by 2.07 mmHg. Each 50 mmol reduction in sodium intake was associated with a 1.10 mmHg decrease in systolic blood pressure and 0.33 mmHg in diastolic blood pressure. The blood pressure-lowering effects were most significant in older adults, non-white populations, and individuals with higher baseline blood pressure, with long-term interventions showed the strongest effects [35].

Observational studies have demonstrated the relationship between sodium intake and other CVD outcomes, including ischaemic heart disease and stroke. For example, the Finnish cohort study (2001) showed a high sodium intake was associated with increased coronary heart disease, CVD, and all-cause mortality [36]. A meta-analysis of 19 prospective studies, with follow-up periods ranging from 3.5 to 19 years and involving over 11,000 cardiovascular events, found an association between high salt intake and a 23% increased risk of stroke, along with a non-significant positive trend in CVD risk. The analysis also showed that the strength of these associations was greater with larger differences in salt intake and longer follow-up durations [37].

Clinical trials of dietary sodium reduction and CVD outcomes are fewer, due to methodological difficulties associated with adherence to dietary change over long periods of time. The Trials of Hypertension Prevention (TOHP) Phase 1 and 2 trials demonstrated a reduction in blood pressure with sodium reduction at three years as a randomized controlled trial [38]. Extended follow-up of participants in the trials has demonstrated a 25% decrease in risk of a cardiovascular event among those in the sodium reduction group [39]. A 20-year follow-up study of TOHP participants further revealed a direct linear relationship between higher sodium intake and increased mortality [40, 41]. The pooled analysis of trials including the TOHP demonstrated a 20% reduction in CVD events with dietary salt reduction, supporting international guidance on the benefits of reducing population salt intake [42].

Comprehensive evidence from well-designed studies, especially those with precise salt intake measurements, has shown a strong positive relationship between salt intake and blood pressure, as well as a direct linear association with CVD and all-cause mortality, extending to salt intakes below 5 g/day [43]. However, a small number of observational studies have sparked controversy concerning the optimal sodium intake level for minimising CVD risk, suggesting a “J- or U-shaped” relationship between sodium intake and CVD risk [44, 45]. This has led some in the academic community to question the recommendations of WHO and others to reduce dietary sodium [46]. Critical methodological analyses indicate that such non-linear associations are largely driven by systematic errors in sodium intake estimation, especially when spot urine samples are used with predictive equations. These methods tend to overestimate intake at low levels and underestimate it at high levels, creating an artificial J-shaped curve that does not reflect true intake patterns [47, 48]. The evidence from these few observational studies has not changed the recommendations from guidelines around the world, which are based on systematic reviews and meta-analyses of well-conducted clinical trials [6, 49].

While sodium and potassium are central to blood pressure regulation, other electrolytes—particularly magnesium—also play important roles in cardiovascular physiology and may exert synergistic protective effects. Magnesium is a cofactor in hundreds of enzymatic reactions and contributes to vascular tone modulation, endothelial function, and the prevention of vascular calcification. Low serum magnesium levels have been associated with increased risks of hypertension, arrhythmias, and cardiovascular mortality. Additionally, calcium homeostasis interacts with sodium transport and vascular contraction mechanisms, although its role in blood pressure regulation remains complex. Considering the broader electrolyte environment—including magnesium and calcium—may enhance mechanistic understanding and improve the effectiveness of dietary strategies aimed at preventing cardiovascular disease [50, 51]. This supports a total diet approval for blood pressure, which is optional.

The gold standard method of measuring sodium intake is to collect a 24-hour urine sample, since around 90% of ingested sodium is excreted via the kidneys over the same period. Due to day-to-day variability in sodium intake in most societies and populations, an accurate measure of usual sodium intake in individuals requires between three and ten 24-hour urine collections per person [52, 53]. Dietary assessment is often used to estimate sodium intake in population health surveys, as dietary measures can provide information about the sources of sodium intake as well as the overall quantity. Dietary assessment tools, such as 24-hour diet recall and food frequency questionnaires, are generally accepted to be less accurate of total sodium intake than 24-hour urine, partly due to difficulty in measuring discretionary salt, and variability in sodium concentration in different foods in the same category [54, 55]. Spot urine collection has also been used as a cheap and convenient alternative to 24-hour urine collection, and a number of formulae have been published to convert the sodium concentration in a spot urine sample into an estimate of 24-hour excretion [56]. Although spot urine collection may be useful to produce a population mean intake for monitoring levels over time, multiple studies have demonstrated that estimates based on spot urine are inaccurate at an individual level. Spot urine should therefore not be used to measure individual sodium intake in epidemiological studies examining associations between sodium intake and health-related outcomes [53].

Importantly, many observational studies linking sodium intake with cardiovascular outcomes are limited by exposure misclassification due to imprecise measurement methods, particularly when relying on spot urine or dietary recall data. These methods introduce substantial within-person variability and systematic error, undermining the accuracy of sodium intake estimates [57]. In a review by the American Heart Association, over 90% of observational studies examining sodium-CVD associations were found to contain multiple high-impact methodological flaws, including systematic exposure error and reverse causality [48]. Addressing these limitations is critical for deriving valid inferences about sodium and cardiovascular risk.

The WHO dietary guidelines for sodium recommends that adults consume less than 2 g of sodium per day (equivalent to around 5 g of salt per day), with lower levels recommended for children proportional to energy intake. Despite this, studies show that sodium consumption among most of the world’s adult population ranges from 2.3 to 4.6 g/day, the global average sodium intake is estimated to be 4.31 mg/day (equivalent to 10.78 g/day salt). This leads to almost 2 million deaths each year [5].

Patterns of sodium consumption vary by income level, with processed foods accounting for the majority of intake in high-income countries, and discretionary salt use at home playing a larger role in low- and middle-income countries. Given these regional differences in dietary sources of sodium, many countries and regions worldwide have established tailored strategies and guidelines to mitigate the health risks associated with excessive salt consumption. These recommendations are generally aligned with the WHO’s guideline of no more than 2 g of sodium per day (equivalent to 5 g of salt) and are usually based on systematic reviews of relevant scientific literature. These national and regional targets reflect a shared global commitment to sodium reduction, adapted to local dietary habits and public health goals.

As outlined in Table 1 (Ref. [5]), actual sodium intake in many populations far exceeds

national and international recommendations. For instance, the United States and

Canada recommend an upper limit of 2.3 g sodium/day (approximately 5.75 g

salt), and the United Kingdom recommends no more than 6 g/day. Countries like

Malaysia [58], Singapore, Australia [59], New Zealand [60], and Peru [61] have

adopted the WHO target of

| Country/Region | Actual salt intake (g/day) | Recommended maxium salt intake (g/day) |

| WHO guideline and estimated global intake | 10.78 | 5 |

| United Kingdom | 7.10 | 6 |

| America | 8.90 | 5.75 |

| Canada | 9.10 | 5.75 |

| Finland | 8.40 | 5 |

| Malaysia | 10.50 | 5 |

| Singapore | 11.50 | 5 |

| Australia | 7.40 | 5 |

| New Zealand | 8 | 5 |

| China | 17.70 | 5 |

| Peru | 9 | 5 |

Note: National recommendations are derived from relevant guidelines; population-level intakes are based on the WHO Global Report on Sodium Intake Reduction [5].

Global sources of dietary sodium intake exhibit substantial variation across regions, shaped by cultural and dietary practices, and are broadly divided into discretionary (salt or salty sauces and condiments added during cooking or at the table) and non-discretionary sources (salt present within foods naturally, and that added during food processing). In many countries, such as Brazil, China, Costa Rica, Guatemala, India, Japan, Mozambique, and Romania, more than half of total salt intake is derived from discretionary sources. Average adult salt intake in these countries ranges from 5.2 to 15.5 g/day [64, 65].

Conversely, in countries that follow Western dietary patterns, non-discretionary sources, especially processed food and instant foods, contribute to 75–80% of overall dietary salt consumption. The high dependence on processed foods and ready-to-eat meals markedly increases sodium intake in these areas. Many studies showed that savoury fast food contributes substantially to population sodium intake [66, 67, 68]. Bread products, cereals and grains, processed meat products, and dairy products have become the leading sources of dietary salt intake in most populations [64], while increasing consumption of fast food and restaurant meals further contributes to non-discretionary sodium intake, highlighting the public health challenge of reducing sodium exposure associated with dietary habits.

WHO has published guidance for the development and implementation of evidence-based comprehensive approachs to population dietary sodium reduction aimed at preventing NCDs. Importantly, WHO recommends the implementation of a multipronged salt reduction strategy led by the government. Guidance includes the SHAKE (a technical package for salt reduction) package [69], sodium benchmarks [7, 70] , country score cards [5] , and use of LSSS [10] to guide and evaluate progress in sodium reduction policies globally.

The WHO SHAKE Technical Package, first released in 2016 for salt reduction, provides Member States with a structured, evidence-based framework for developing and implementing sodium reduction strategies. An updated version of the SHAKE Package, featuring a suite of action menus, is due in 2025 [10]. This framework comprises five key components: surveillance, to track sodium consumption levels and associated health impacts; harnessing industry collaboration to encourage reformulation of food products; adopting labelling and marketing standards to better inform consumers; knowledge dissemination, aimed at educating the public on the health risks of high sodium intake; and environmental changes to create food environments supportive of lower sodium options [69]. The SHAKE package also offers a range of toolkits and resources designed to support countries in both implementing and monitoring these strategies, ultimately aiming to reduce population-wide sodium intake.

The extent to which different strategies from the SHAKE technical package should be emphasized will be country-specific and based on local sodium/salt consumption patterns. A critical component of the surveillance workstream is the accurate measurement of salt intake and consumption sources. This includes the use of 24-hour urinary sodium excretion and detailed dietary surveys to identify major sodium sources. Importantly, reliance on spot urine samples and estimation formulas has been shown to introduce significant bias, leading to misleading interpretations. Recent evidence has demonstrated that only 24-hour urinary sodium assessments reveal a true linear association between sodium intake and blood pressure/hypertension risk—without evidence of a threshold below which sodium intake is ‘safe’. Therefore, the use of accurate, unbiased sodium exposure assessment methods is essential for guiding effective salt reduction strategies. In populations where discretionary salt contributes significantly to total intake, interventions should prioritize education and the promotion of low-sodium salt substitutes [20]. Conversely, in settings where the vast majority of intake is from processed foods, food reformulation in collaboration with the food industry is a key strategy.

To inform food reformulation strategies (Harnessing Industry in the SHAKE acronym), WHO has produced a list of sodium benchmarks, suggesting maximum sodium concentration levels in processed foods that can be used to inform reformulation programs. These were developed from a technical consultation process that involved analysis of global sodium concentration information and targets. The benchmark values are category-specific and are based on the ‘Lowest maximum value for each subcategory from existing national or regional targets’, ensuring that the level is feasible with respect to palatability and food safety [7]. Benchmarks produced in 2021 were revised in 2024 and include values for 18 categories and 70 subcategories [70]. Global adoption of the benchmark values, either as mandatory or voluntary targets, is recommended to reduce population sodium intake.

Effective front-of-pack food labelling to enable consumers to identify high-salt foods (Adopt Standards for Labelling and Marketing) is essential for the Knowledge strand of the package, and contributes to the development of a healthy eating Environment. The Environment strand also includes work in settings in schools, workplaces, and hospitals to procure and povide reduced and low-salt foods [69].

As part of its global surveillance programme, WHO developed Sodium Country Score Cards to track Member States’ progress in adopting and implementing sodium reduction policies [5]. These score cards rate countries based on the types and extent of sodium reduction measures, distinguishing between mandatory and voluntary policies. The score cards also support the Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases 2013–2020, endorsed by the 66th World Health Assembly, by tracking progress towards WHO’s target of a 30% reduction in average population sodium intake by 2025 and documenting national policy commitments along with sodium-related measures within nutrient profile models [71]. Evidence suggests that mandatory policies are particularly effective, offering broader population coverage, protecting against commercial interests, and ensuring a level playing field for food manufacturers [5]. According to the 2023 WHO global report, just over half (55% or 119) of 194 Member States have implemented policies and interventions to reduce sodium intake through mandatory (5%; n = 9), a mix of mandatory and voluntary (27%; n = 53) or voluntary (29%; n = 57) approaches [5].

Despite global salt reduction programmes and interventions progress towards the global action plan target to reduce population sodium intake by 30% by 2025 has been slow, with sodium intake in many countries still exceeding recommended levels [5]. In response, WHO revised its target in 2021, setting a more ambitious goal of a 40% reduction in population sodium intake by 2030, reflecting the need for intensified global action to address high sodium consumption and its associated health risks [72].

The salt reduction programme in the United Kingdom, launched in 2003, serves as a model of public health intervention. Key measures comprised public awareness projects, transparent nutritional labelling using the ‘traffic light’ front of pack format, and voluntary partnerships with the food industry to reformulate products and decrease salt levels. A series of decreasing targets for sodium concentration in a wide range of processed foods was published during the life of the programme. Regular 24-hour urinary sodium surveys were conducted to monitor trends in salt intake, combined with public disclosures of non-compliant food products or manufacturers to ensure industry accountability [73].

From 2003 to 2011, the average daily adult salt consumption in England declined by 15%, from 9.5 g to 8.1 g [73]. The reduction was associated with important public health benefits, such as a 3 mmHg decline in average systolic blood pressure and a 36% decrease in mortality rates from stroke and ischemic heart disease over the period [74]. Despite these achievements, challenges persist in sustaining momentum and reaching the ultimate salt intake goal of a maximum salt intake of 6 g/day established by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Progress on the programme appeared to stall following the implementation of the United Kingdom ‘responsibility deal’ where a greater emphasis was placed on industry self-regulation [75]. Dietary salt reduction has since plateaued with the most recent mean estimated salt intake for adults in England at 8.4 g/day (equivalent to around 3.36 g/day sodium) [76].

The European Union launched the EU Salt Reduction Framework in 2008, targeting a voluntary 16% reduction in salt intake over four years. The initiative encouraged member states to focus on high-sodium food categories—such as bread, meat products, and ready meals—through reformulation efforts and public education. National programs were developed in alignment with this framework, supported by scientific guidance from the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). The EU Salt Campaign further promoted consumer awareness and industry engagement across member states. By 2012, several countries had reported measurable reductions in the salt content of targeted processed foods, demonstrating the potential of coordinated, multisectoral action at the regional level [77].

The United States has adopted a multi-pronged approach to reduce population sodium intake, primarily through regulatory guidance and community-based initiatives. In October 2021, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) released voluntary sodium reduction targets for over 160 categories of packaged and restaurant foods, aiming to lower the national average sodium intake from approximately 3.4 g to 3 g/day over 2.5 years [78]. Building on this, the FDA issued draft guidance in August 2024, proposing updated 3-year reduction targets that could further reduce intake to 2.75 g/day if fully implemented [79]. These policies emphasize gradual reformulation and industry collaboration to ensure both feasibility and consumer acceptance.

In parallel, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) launched the Sodium Reduction in Communities Program (SRCP), which supports local governments and institutions in expanding access to low-sodium food options, particularly in schools, hospitals, and community organizations [80]. Together, these efforts represent a comprehensive strategy to reduce sodium intake through both national-level regulation and grassroots public health interventions.

Finland’s salt reduction program, initiated in the late 1970s, key strategies included public health campaigns to raise awareness of the adverse health effects of a diet high in sodium, mandatory sodium labeling on processed foods, collaboration with the food industry to reformulate products to contain less sodium, and the introduction of potassium-enriched salt substitutes. These efforts resulted in a decrease in average daily salt intake from 14 g in the 1970s to approximately 10 g by the early 2000s, marking a one-third reduction [81]. During the same period, population blood pressure levels declined by over 10 mmHg, while stroke and coronary heart disease mortality among middle-aged adults dropped by 80%. Life expectancy increased by 5–6 years, with reduced sodium intake identified as a major contributing factor, particularly through its impact on lowering blood pressure. Notably, this improvement occurred despite increases in body mass index and alcohol consumption during the same period [82, 83].

Other dietary and lifestyle changes also contributed to the decline in CVD. These included increased potassium intake through the use of potassium- and magnesium-enriched salts, higher consumption of fruits and vegetables, reduced fat intake, and a significant reduction in male smoking rates [82].

Since 2006, Croatia has implemented a phased national salt reduction program, the Croatian Action on Salt and Health (CRASH). Key interventions have included public education campaigns, mandatory reductions in salt content for bread and bakery products (reduced to 1.3% by 2022) [84], and collaboration with the food industry, which has achieved a 25% reduction in salt content in leading meat products. These efforts have resulted in a 15.9% decrease in average salt intake between 2008 and 2020, with larger reductions observed in men compared to women [85]. Additionally, public awareness of the risks associated with high salt intake increased from 65.3% in 2008 to 96.9% in 2023, demonstrating the substantial impact of these initiatives. Despite these achievements, average sodium intake remains above the recommended levels, underscoring the need for continued reformulation efforts, public education, and monitoring to further reduce sodium consumption and improve public health outcomes [85].

Japan’s salt reduction efforts, initiated in the 1970s, have focused on public education and school-based interventions to raise awareness about the health risks of high sodium intake. Additional measures include mandatory sodium content labeling on food products and encouraging the food industry to develop low-sodium alternatives. These initiatives have successfully reduced average salt intake by approximately 30% since the 1970s, though further efforts are required to meet target levels [86].

In China, dietary salt consumption is significantly shaped by home cooking, accounting for roughly 85% of sodium intake. China’s salt reduction programmes, developed in the 1980s, have grown stronger in recent years due to the increasing prevalence of NCDs and the goals established in the “Healthy China 2030” plan [87].

China’s salt reduction strategies include several essential elements: communication and education, reducing salt consumption in home cooking, restaurants, and pre-packaged foods, encouraging the widespread use of low-sodium salt, and consistently monitoring national sodium intake levels and CVD prevalence to enhance intervention approaches [88, 89].

Public health education campaigns have highly enhanced awareness regarding the health risks linked to elevated sodium consumption. By 2025, it is expected that more than 80% of the population will acknowledge high-sodium diets as a significant health risk. The sodium intake from home cooking is projected to decline from 9.3 g/day in 2019 to an estimated 8.3 g/day by 2025. The sodium content of major dishes in restaurants, canteens, and catering services is projected to decline from 487 mg/100 g in 2020 to 430 mg/100 g by the end of 2025 [90, 91].

The Shandong Salt Reduction Programme (2011–2016) achieved an impressive reduction in daily salt intake among residents, decreasing it from 13.3 g/day to 10.0 g/day. This illustrates the potential effects of strategically designed, region-specific interventions aimed at reducing salt intake and enhancing public health results [92].

The varying outcomes of national salt reduction programs can be attributed to differences in cultural dietary patterns, food industry engagement, government enforcement mechanisms, and public health infrastructure. For example, Finland’s substantial reduction in population sodium intake was facilitated by mandatory sodium labeling, strong governmental oversight, and active reformulation by the food industry. In contrast, China faces more complex challenges due to the prevalence of salt in home cooking, decentralized dietary behaviours, and a larger reliance on public education and voluntary compliance. Regionally, the European Union coordinated multi-country actions through voluntary frameworks and labeling policies, supported by EFSA’s scientific guidance. Meanwhile, the United States implemented national sodium reduction targets via FDA guidance and complemented these with local initiatives such as the CDC’s Sodium Reduction in Communities Program. These distinctions illustrate how structural, cultural, and political contexts influence program effectiveness, highlighting the need for tailored, context-specific strategies in global sodium reduction efforts.

Recent efforts to reduce sodium intake have focused on the use of salt substitutes, which aim to maintain food functionality and sensory qualities while lowering sodium content. Among these, potassium-based substitutes have garnered the most attention, with potassium chloride (KCl) being the most widely used [91]. Its physical and functional properties closely mimic those of NaCl, making it an effective choice for salt reduction. At low concentrations, KCl compensates for reduced saltiness without significantly affecting taste, and blends of NaCl and KCl in various proportions have been extensively studied for this purpose [93]. However, potassium chloride replacement at or above 40% is often associated with increased bitterness, metallic notes, and undesirable off-flavors. While 20–40% substitution levels are generally acceptable, substitution at 60% approaches the limit of sensory acceptability, and at 80%, products are typically deemed unacceptable by consumers [94]. For example, a randomized controlled feeding trial (RCT) over 4 weeks tested the effect on participant choice of a gradual salt reduction in brown bread with and without the use of KCl and yeast extract as flavour enhancers compared with control. This study showed the use of KCl as a flavor enhancer enabled reduction of salt content by up to 67% without reduction in bread consumption [95].

WHO has recently released a new guideline on the use of LSSS, which focuses on the partial replacement of NaCl with KCl. This guideline aim to support policy-makers, programme managers, health professionals and other stakeholders in their efforts to reduce population sodium intake, thereby lowing the risk of hypertemsion and related NCDs. The recommendation specifically addresses the discretionary use of LSSS, such as table salt, and targeted at adults within the general population and explicitly excludes individuals with kidney impairments or other conditions that may impair potassium excretion. Additionally, the recommendation does not apply to children or pregnant women [10].

Beyond KCl, other mineral salts such as magnesium chloride, calcium chloride, ammonium chloride, and lithium chloride have also been investigated for their potential in sodium reduction. While these alternatives aim to lower sodium intake, their adoption faces challenges related to taste and compatibility across diverse food matrices. Additionally, acid salts, phosphates, gluconates, and citrates offer promising avenues for salt replacement but remain underexplored, particularly outside common food categories like protein foods and bakery products [93]. Regulations and standards for salt substitutes in countries like the United States, China, India, and Canada frequently reference (KCl) and other potassium-based substitutes [96].

A scoping review of 117 studies on salt replacers in processed foods revealed that protein foods dominate the research landscape, accounting for 53% of studies, followed by cheese (15%) and grains, including bread (13%). By contrast, food categories such as juices, vegetables, and snacks are underrepresented and warrant more research. Nearly half of combination-method studies have used meat as the model food, emphasizing the need for broader investigations into other food types, including snack foods and condiments. Despite these gaps, salt substitutes like KCl have been successfully incorporated into products such as table salt, bread, cheese, meat products, and sauces [97, 98, 99]. Expanding research to underrepresented food categories and exploring methods such as combining salt replacers with functional modifications or bitter blockers could enhance the efficacy and appeal of sodium reduction strategies. A systematic review and meta-analysis on salt-reduced foods found that salt content could be reduced by approximately 40% in bread and up to 70% in processed meats without significantly affecting consumer acceptability. Outcomes for other food categories showed greater variability. These findings provide valuable guidance for manufacturers, enabling more substantial reductions in salt during food reformulation and contributing to a healthier overall food supply [100].

Research consistently highlights the beneficial effects of potassium intake on blood pressure. A meta-analysis of 33 trials reported that potassium supplementation significantly lowers systolic and diastolic blood pressure, particularly in hypertensive individuals, with the effect amplified in high-sodium environments. This finding underscores the critical role of potassium in mitigating sodium’s impact on blood pressure and emphasizes the importance of a balanced sodium-to-potassium ratio [101]. Building on this, a dose-response meta-analysis of 32 randomized controlled trials identified a U-shaped relationship between potassium supplementation and blood pressure. Adequate potassium (at least 3.51 g/day) intake was shown to considerably reduce systolic and diastolic blood pressure, with stronger effects observed in hypertensive individuals [102]. However, for individuals who need to strictly limit potassium intake, it is recommended to follow medical advice first.

Studies comparing the effects of sodium reduction and potassium supplementation on blood pressure consistently highlight the importance of addressing both electrolytes. A 2-year cluster-randomized controlled trial (Cluster-RCT) conducted in elderly care facilities found that the salt substitute group (KCl) reduced blood pressure more effectively than the salt supply restriction group. Additionally, replacing 25% of NaCl with KCl had a limited impact on sodium excretion [103]. Additionally, a meta-regression analysis of randomized trials demonstrated that reducing sodium intake and increasing potassium independently lower blood pressure, with more pronounced effects observed in hypertensive individuals [104].

The sodium-to-potassium ratio has emerged as a critical factor in cardiovascular and blood pressure regulation. The TOHP follow-up study highlighted the long-term significance of maintaining a balanced sodium-to-potassium ratio, showing that higher baseline ratios were strongly associated with increased CVD risk over a 10–15 year period, underscoring the essential role of electrolyte balance in promoting cardiovascular health [105].

A balanced dietary sodium-to-potassium ratio is particularly effective for blood pressure regulation, with an ideal ratio close to 1.0, corresponding to a daily potassium intake of 70–80 mmol [106, 107]. Evidence from a study in China further demonstrated that increased sodium intake elevates blood pressure, while higher potassium intake has a protective effect. Additionally, a higher sodium-to-potassium ratio was strongly linked to higher blood pressure, with the most pronounced effects observed in low-salt regions [108]. These findings highlight the importance of reducing sodium intake while increasing potassium consumption to achieve optimal blood pressure control and reduce long-term CVD risk [109].

The Salt Substitute and Stroke Study (SSaSS), involving 20,995 participants with a mean age of 65.4 years over an average follow-up of 4.74 years, revealed that the use of a salt substitute (75% sodium chloride, 25% potassium chloride) significantly decreased the incidence of stroke (14%), major cardiovascular events (13%), and all-cause mortality (12%) relative to regular salt in individuals with prior history of stroke or those aged 60 years and older with hypertension. The rate of severe adverse events related to hyperkalemia was not significantly elevated in the salt replacement group, indicating its cardiovascular advantages and safety in high-risk individuals [110]. Similarly, a meta-analysis emphasized that reducing the sodium-to-potassium ratio is strongly associated with blood pressure reduction, advocating for strategies that combine sodium reduction with increased potassium intake to achieve optimal cardiovascular health outcomes [111].

The 2022 Cochrane review by Brand et al. [112] provides robust evidence supporting the use of LSSS as an effective strategy for improving cardiovascular health. The analysis revealed that LSSS significantly reduced systolic blood pressure (by 4.76 mmHg) and diastolic blood pressure (by 2.43 mmHg) compared to regular salt. Additionally, slight reductions were observed in the incidence of non-fatal stroke, acute coronary syndrome, and cardiovascular mortality. The evaluation clearly emphasised the safety of LSSS in the majority of adult populations, as its use elevated blood potassium levels without substantially increasing the risk of hyperkalemia. The review emphasised a lack of information about its effects on children and pregnant women, indicating the necessity for additional research in these populations. These findings show the value of LSSS as a viable, population-wide strategy for decreasing sodium consumption and lowering cardiovascular risk [112].

The EFSA considers potassium intake from food sources up to 5–6 g/day and long-term supplementation up to 3 g/day as low risk for healthy adults, as no upper limit for potassium intake has been established. However, studies indicate that globally, potassium consumption falls short of the WHO guidelines in many countries, including the United States and the United Kingdom, where 80% and 95% of adults, respectively, fail to meet recommended intake levels [113]. Replacing sodium chloride with potassium chloride in food reformulation offers a promising strategy to increase potassium intake. A modeling study demonstrated that substituting sodium chloride with potassium chloride in products such as bread, processed fruits and vegetables, snacks, and processed meat could help populations achieve the potassium intake guideline of 3.51 g/day. Furthermore, this substitution is considered safe for the general population, with intake levels remaining within EFSA recommendations [114].

Potassium-based salt substitutes are generally safe and beneficial for healthy individuals and are widely recommended for people with hypertension. Formulations containing approximately 75% sodium chloride and 25% potassium chloride are particularly common, striking a balance between sodium and potassium intake to support health, provided there are no contraindications such as advanced kidney disease (stages 4 and 5), the use of potassium supplements, or potassium-sparing diuretics [115]. For the general population, where the likelihood of advanced kidney disease is low, potassium-enriched, low-sodium salt with this recommended ratio (75:25 sodium to potassium) is a valuable alternative [116].

When implementing LSSS at the national level, countries should ensure safety concerns are addressed and closely monitor potential risks, such as hyperkalaemia or impaired potassium excretion. In addition to excluding populations that require potassium intake restrictions, key considerations include demographics and trends of at-risk groups, healthcare access for kidney monitoring, and mode of use (e.g., discretionary vs. non-discretionary) and product types (e.g., table salt vs. manufactured foods). Monitoring should track potassium substitution levels, sodium and potassium intake trends, and shifts in at-risk populations. Regulatory measures, including warning labels, health claims, and public education, are essential [10].

A range of technological strategies has been developed to reduce sodium content in processed foods while maintaining sensory acceptability. These approaches target different aspects of taste perception and food structure to compensate for reduced salt levels. Among the most widely applied are chemical interventions such as flavour enhancers, including monosodium glutamate (MSG), umami peptides, and yeast extracts, which intensify savory perception and help preserve palatability in low-sodium products [117]. In addition, bitter blockers and masking agents are frequently used alongside potassium-based salt substitutes to mitigate off-flavours and improve consumer acceptance [118]. Cross-modal strategies, such as pairing salty-associated aromas or complementary sour notes, are also being explored to enhance saltiness perception via multisensory integration [119].

Complementing these perceptual strategies, physical and structural modifications offer further potential for sodium reduction. Microencapsulation techniques allow for controlled salt release and spatial targeting within the food matrix, thereby enhancing local salt perception while reducing overall sodium content [120, 121]. Similarly, approaches like spatial salt distribution and aeration increase the efficiency of salt delivery to taste receptors, amplifying perceived saltiness even at lower sodium levels [122].

This paper has several strengths. It updates a broad range of literature regarding the health effects of sodium intake and includes the latest data and recommendations regarding the use of salt substitutes to lower sodium intake and increase potassium intake. It is a comprehensive narrative review; however, it is not a systematic review, so it does not include data about every country, and does not include all guidelines relating to sodium and potassium intake and policies.

Reducing sodium intake is a cornerstone of global efforts to lower blood pressure and CVD risk. Public health authorities and research institutions worldwide have established sodium and potassium intake guidelines tailored to age, gender, and health conditions, aiming to reduce sodium consumption—particularly from high-sodium processed foods—while encouraging potassium intake through fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. Despite variations in numerical targets between countries, the shared objective remains the prevention of hypertension and related diseases through dietary balance [123].

However, few populations achieve recommended sodium intake levels, and progress toward global targets has been slow. WHO recommends comprehensive salt reduction programs targeting multiple sources of sodium intake, including discretionary salt, processed foods, restaurant meals, and takeaways. Given that high-sodium foods are deeply embedded in many dietary patterns, reducing sodium intake at an individual level remains challenging and requires gradual adjustments to taste preferences.

While clinical studies have shown that highly motivated individuals can achieve and maintain reduced sodium intake, environmental change is also required for meaningful sodium reduction at a population level. Evidence suggests that nutrition education programs and food reformulation can effectively lower both systolic and diastolic blood pressure, emphasizing the importance of strengthening public health education to support compliance and sustain sodium reduction efforts.

Use of LSSS is a promising intervention, particularly when sodium is replaced with potassium. These salts are especially beneficial in settings where a large proportion of sodium intake comes from discretionary salt. However, ensuring the safety of potassium-based salt substitutes for at-risk populations is crucial to promoting broader adoption. For populations where discretionary salt use is already very low, it is crucial to ensure that LSSS guidance does not inadvertently encourage an increase in discretionary salt consumption. Moreover, sodium and potassium intake should be balanced alongside other dietary factors to promote healthy diets and prevent diet-related NCDs.

Despite progress in LSSS research and implementation, several critical research gaps remain. Further studies are needed to clarify the safety implications of widespread LSSS use, particularly regarding hyperkalaemia risk, in high-risk populations, and overall sodium-potassium balance. More generalizable evidence is required from monitored trials and prospective cohort studies to assess the effectiveness and safety of LSSS across diverse populations, including normotensive individuals, those without a history of cardiovascular disease, children, pregnant women, and individuals with relatively low baseline sodium intake.

Additionally, research should explore alternative LSSS formulations beyond potassium-based substitutes, as well as the long-term impact of LSSS use on dietary behaviors, sodium reduction sustainability, and total potassium intake from various food sources. Further investigation is also needed on LSSS use in processed foods, sauces, and condiments, as well as its implications for iodization programs and multisectoral sodium reduction strategies. Lastly, evidence on the economic feasibility, affordability, and accessibility of LSSS is also crucial for informing policy decisions and equitable large-scale adoption [10].

The food industry plays a critical role in sodium reduction but often resists reformulation due to cost concerns and the economic benefits of high-sodium products. Sodium enhances flavor, preserves shelf life, and increases product weight, making it financially attractive for manufacturers. This industry reluctance highlights the need for stronger regulatory frameworks and economic incentives to drive sodium reformulation. Gradual sodium reduction in processed foods, improved food labeling, and targeted public education are essential practical strategies to facilitate behavior change. Collaboration between policymakers, health organizations, and the food industry will be key to overcoming existing barriers.

Reducing sodium intake offers undeniable benefits in the prevention and management of CVD, including lowering blood pressure and reducing CVD incidence, morbidity, and mortality. However, ensuring meaningful and sustainable progress on a global scale requires continuous efforts that are tailored to regional contexts and populations. Key strategies include targeted nutritional education, reformulation of processed and restaurant foods by the food industry, and strengthening regulatory frameworks around food labelling and marketing.

To achieve long-term success, international collaboration and further research are essential to fill existing evidence gaps and refine sodium reduction strategies. A collective commitment to reducing sodium intake has the potential to significantly enhance cardiovascular health and save millions of lives worldwide.

WHO, World Health Organization; NaCl, sodium chloride; CVD, cardiovascular diseases; NCDs, non-communicable diseases; RAAS, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system; DASH, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension; RCTs, randomized controlled trials; TOHP, Trials of Hypertension Prevention; EU, European Union; SHAKE, Surveillance, Harness industry, Adopting standards for labelling and marketing, Knowledge, Environmental; NICE, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; CRASH, the Croatian Action on Salt and Health; KCl, potassium chloride; SSaSS, The Salt Substitute and Stroke Study; LSSS, lower-sodium salt substitutes; FDA, the Food and Drug Administration; CDC, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; SRCP, the Sodium Reduction in Communities Program; EFSA, the European Food Safety Authority.

NH and RMcL designed the draft and reviewed the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. Both authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.