1 Department of Pathology, College of Medicine, Taif University, 21944 Taif, Saudi Arabia

2 Department of Microbiology, College of Medicine, Taif University, 21944 Taif, Saudi Arabia

3 Department of Clinical Laboratory Sciences, College of Applied Medical Sciences, Taif University, 21944 Taif, Saudi Arabia

4 Department of Biotechnology, College of Sciences, Taif University, 21944 Taif, Saudi Arabia

5 Department of Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, Al Azhar University, 11651 Damietta, Egypt

6 Department of Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, Horus University, 44921 Damietta, Egypt

7 Radiological Sciences Department, College of Applied Medical Sciences, Taif University, 21944 Taif, Saudi Arabia

8 Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, College of Pharmacy, Qassim University, 51452 Buraidah, Saudi Arabia

9 Department of Physiology, College of Medicine, King Saud University, 11461 Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

10 Department of Human Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University, 12613 Cairo, Egypt

Abstract

Advancements in the management of toxicity-induced injury have led to improvements in disease prognosis. However, exposure to certain chemical substances can lead to toxic effects on various body cells and may contribute to infertility. Curcumin has an antioxidant effect on receptors in gonadal cells. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the ability of curcumin to restore thioacetamide-induced changes in germ cells.

A total of four groups were each allocated eight rabbits: Group I, the control group; Group II, the curcumin (Curc) group; Group III, the thioacetamide (TAA) group; Group IV, the TAA and Curc group. After the rabbits were sacrificed and the testes removed, the tissues were fixed and stained with hematoxylin–eosin (H&E). The sections were evaluated to assess the histological and spermatogenesis-associated changes. Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS 17.0, with p < 0.05 considered significant.

The serum testosterone level was significantly decreased in Group III (271.40 ± 101.20) compared to Groups I, II, and IV (435 ± 67.50; 457 ± 58.60; 398.80 ± 119.40, respectively). Moreover, marked improvement was observed in the oxidative stress induced by TAA following curcumin treatment for most measured parameters in the study. Histological examination using Johnson's testicular biopsy score (JTBS) criteria and mean seminiferous tubules diameter (MSTD) scores revealed an ameliorative effect of curcumin treatment against the toxic impact of TAA (JTBS was 6.55 ± 1.37 in the TAA group compared to 9.25 ± 0.83 in the TAA and curcumin group; MSTD was 235.90 ± 20.50 in the TAA group compared to 262 ± 15.14 in the TAA and curcumin group).

Curcumin decreases the cytotoxic effects of thioacetamide on germ cells, with the addition of improving the oxidants/antioxidants markers and testicular function in rabbits.

Keywords

- curcumin

- thioacetamide

- oxidative stress

- germ cell injury

- testosterone levels

- histological evaluation

Various diseases, such as diabetes, obesity, and toxic substances, can affect the male genital system [1]. Oxidative stress, hypoxia, and toxicity caused by different diseases trigger testicular damage [2]. Heat shock proteins are present in cells exposed to stress factors, such as high temperatures [3]. Thioacetamide (TAA; CH3CSNH2) is an organosulfur compound that can prevent the germination of fungal spores and is used as a fungicidal chemical [4, 5]. TAA is an ideal toxicant due to its water-soluble nature and its ability to induce severe damage [6]. Moreover, in the qualitative inorganic analysis, TAA is widely used as a source of sulfide ions in situ to replace hydrogen sulfide [7]. Human exposure routes to TAA include inhalation, ingestion, and dermal absorption [8]. Acute TAA exposure causes changes in calcium membrane permeability due to the impairment of calcium entry to the cells, leading to hepatic and renal apoptosis [9]. Additionally, TAA bioactivation generates thioacetamide S-oxide, which leads to the formation of peroxide radicals and the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [10]. These ROS will initiate oxidative reactions or trigger reactions involving sulfhydryl compounds, causing liver injury [11]. The subsequently released metabolites are distributed among several tissues, including the liver, kidney, gonads, adrenal glands, and bone marrow [12]. Therefore, these metabolites may alter amines, proteins, and lipids, causing advanced oxidative stress and cytokine release [13]. Notably, curcumin is recognized as a potent endogenous antioxidant [14]. Testicular cells exhibit continuous mitotic activity, whereas tissue integrity is crucial for maintaining healthy spermatogenesis. Oxidative stress may lead to sperm dysfunction due to tissue toxicity. Therefore, ROS production should be minimal to promote normal capacitation and acrosomal functions of spermatocytes. Glutathione peroxidase, superoxide dismutase, glutathione, and inherent antioxidant levels may show elevated levels as a compensatory response to increased oxidative stress [15, 16]. Meanwhile, curcumin acts as a scavenger against the most toxic reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. Thus, the use of exogenous curcumin effectively reduces inflammation and oxidative stress due to the associated free radical scavenger ability [17, 18]. Curcumin can pass through the barriers of various organs and, upon administration, has been shown to promote a prophylactic antioxidant effect against oxidative stress in several experimental and clinical conditions [19, 20]. The therapeutic properties of curcumin have also been attributed to its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects [21, 22, 23].

Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the effect of curcumin on improving oxidative stress and the quality of spermatogenesis.

This study was conducted in the Faculty of Medicine, Al Azhar University, Damietta, Egypt, between June 2023 and June 2024.

Thioacetamide and curcumin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Gallen, Buchs, Switzerland).

A total of 32 male New Zealand White Rabbits (5–6 months old; average body weight 2.0 kg) were obtained from the experimental and clinical research center, Al Azhar University, Egypt. These rabbits were housed in plastic cages in a well-ventilated rat house. Each rabbit was fed 100 g per day of a standard commercial rabbit chow and had free access to water; a 12 h light/dark cycle was also maintained. At the end of the experimental period, the animals were deeply anesthetized via intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (35 mg/kg) and xylazine (5 mg/kg). After rigorously confirming complete loss of pain perception using multiple methods, including the interdigital pinch reflex, the animals were rapidly decapitated.

The rabbits were randomly assigned to four groups, each consisting of eight rabbits.

Group I: served as control.

Group II: Curcumin (Curc) group: Rabbits were supplemented daily with curcumin by oral gavage. Curcumin was dissolved in 1% carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) at a concentration of 2% and was administered orally (100 mg/kg b.wt./day).

Group III: Thioacetamide (TAA) group (300 mg/kg) twice, with 24-hour intervals.

Group IV: TAA (300 mg/kg intra peritoneal) and Curc (100 mg/kg b.wt./day) group.

At the end of the experimental period, animal decapitation was performed under

intraperitoneal 5% ketamine (35 mg/kg) and 2% xylazine (5 mg/kg) anesthesia. The

testicular tissues were removed and fixed rapidly in Bouin’s fixative for the

histological examination. Dehydration, clearing, and embedding were performed in

paraffin. Sections were stained with hematoxylin–eosin (H&E), and photographs

were taken using a light microscope (Olympus Corporation, Hachioji, Tokyo,

Japan). Johnsen’s testicular biopsy score (JTBS) and mean seminiferous tubule

diameter (MSTD) were applied to evaluate spermatogenesis. Tubules with complete

inactivity were considered as a score of 1, and tubules with maximum activity,

with at least 5 spermatozoa, were viewed as a score of 10. MSTD was measured in

micrometers using a 200

Blood was collected from the tail vein of rabbits before sacrificing. Testicular tissue was homogenized, and the homogenate was collected for the assessment of oxidative stress biomarkers. The level of reduced glutathione (GSH) was evaluated as described by Vukšić et al. [25]. The method employed by Mihara and Uchiyama [26] was used to estimate tissue malondialdehyde (MDA) content. Catalase (CAT) activity was measured as described by Aebi [4, 27]. The required CAT amount to decompose 1 mol of hydrogen peroxide per min at pH 7 and 25 °C was defined as one unit of activity. Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity was estimated according to the method described by Marklund [28]. Glutathione peroxidase (GPx) activity was measured using a glutathione peroxidase assay kit (ab102530; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The results are expressed as units/mg protein. Plasma total antioxidant capacity (TAC) was measured using the total antioxidant capacity kit provided by Abcam (Cambridge, UK), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The results are expressed as Trolox equivalents.

Blood samples were collected into empty tubes to obtain serum, and then centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min. The serum testosterone levels were determined using ELISA kits. Homogenized testicular tissue was centrifuged to remove supernatants [29]; the supernatants were used to analyze the total antioxidant status (TAS) and total oxidant status (TOS) using the ELISA method. ELISA kits for testosterone, TAS, and TOS were provided by Shanghai Sunred Biological Technology Co., Ltd (Kit numbers: 201-11-5126, DZE201112672, DZE201111669, respectively). ELISA methods were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows version 17.0

(SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The distribution of the samples in the groups was

analyzed using a one-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The data are expressed as

the arithmetic mean and standard deviation. A one-way analysis of variance

(ANOVA) test was used to assess the differences among the groups. A two-sided

p-value

A statistically significant difference was observed for the blood serum testosterone levels between the groups. Serum testosterone and TAS levels were significantly decreased in Group III. Furthermore, the TOS was decreased in Group III compared to Groups I, II, and IV, although the difference was not statistically significant. The curcumin-treated groups were relatively similar to the control group (Table 1).

| Parameters | Group I | Group II | Group III | Group IV | p-value |

| Testosterone (pg/mL) | 435 |

457 |

271.40 |

398.8 |

0.0014 |

| TAS (U/mL) | 8.53 |

8.85 |

1.96 |

8.27 |

0.0049 |

| TOS (nmol/mL) | 1.43 |

1.44 |

2.20 |

1.38 |

0.1000 |

-Values are expressed as the mean

-Note: Group I (control group), Group II (Curc group), Group III (TAA group), Group IV (TAA + Curc). There was a statistically significant difference between the groups in TAS status.

-Abbreviations: Curc, curcumin; TAA, thioacetamide; TAS, total antioxidant status; TOS, total oxidant status.

aSignificant difference from the control group.

bSignificant difference from the curcumin-treated group.

cSignificant difference from the thioacetamide-treated group.

Table 2 shows a significant difference between the four studied groups in terms of oxidant parameters (MDA and nitric oxide (NO). The thioacetamide-treated group exhibited significantly higher oxidant parameters compared to the other groups. The antioxidant parameters were significantly higher in Groups I and II in comparison to Group III. Regarding the oxidant/antioxidant analysis, Group IV, which was treated with both curcumin and thioacetamide, showed an ameliorative effect compared to Group III, which was treated with thioacetamide only.

| Parameters | Group I | Group II | Group III | Group IV | p-value |

| MDA (nmol/mg protein) | 1.63 |

1.14 |

4.65 |

2.76 |

|

| NO (µmols/L) | 4.78 |

4.24 |

14.54 |

7.87 |

|

| GSH (ug/mg protein) | 6.54 |

6.92 |

2.37 |

4.66 |

|

| GPx (U/mg protein) | 23.40 |

25.11 |

10.73 |

19.32 |

|

| CAT (umoles of H2O2 consumed/min/mg protein) | 5.21 |

6.32 |

2.68 |

4.39 |

0.0043 |

-Values are expressed as the mean

-Note: Group I (control group), Group II (Curc group), Group III (TAA group), Group IV (TAA + Curc).

-Abbreviations: TAA, thioacetamide; TAS, total antioxidant status; TOS, total oxidant status; MDA, malondialdehyde; NO, nitric oxide; GSH, glutathione; GPx, glutathione peroxidase; CAT, catalase.

aSignificant difference from the control group.

bSignificant difference from the curcumin-treated group.

cSignificant difference from the thioacetamide-treated group.

According to JTBS, Groups I, II, and IV were relatively similar in terms of histological structure; however, a statistically significant decrease was observed in Group III compared to Groups I and II. There was also a statistically significant decrease in the MSTD of Group III. Thus, curcumin was shown to reduce the damage of spermatogenic cells induced by thioacetamide (Table 3).

| Groups | Group I | Group II | Group III | Group IV | p-value |

| JTBS | 9.33 |

9.46 |

6.55 |

9.25 |

0.0043 |

| MSTD (u) | 276 |

279 |

235.90 |

262 |

0.0024 |

-Values are expressed as the mean

-A p-value

-Note: Group I (control group), Group II (Curc group), Group III (TAA group), Group IV (TAA + Curc).

-Abbreviations: Curc, curcumin; TAA, thioacetamide; JTBS, Johnsen’s testicular biopsy score; MSTD, mean seminiferous tubule diameter.

aSignificant difference from the control group.

bSignificant difference from the curcumin-treated group.

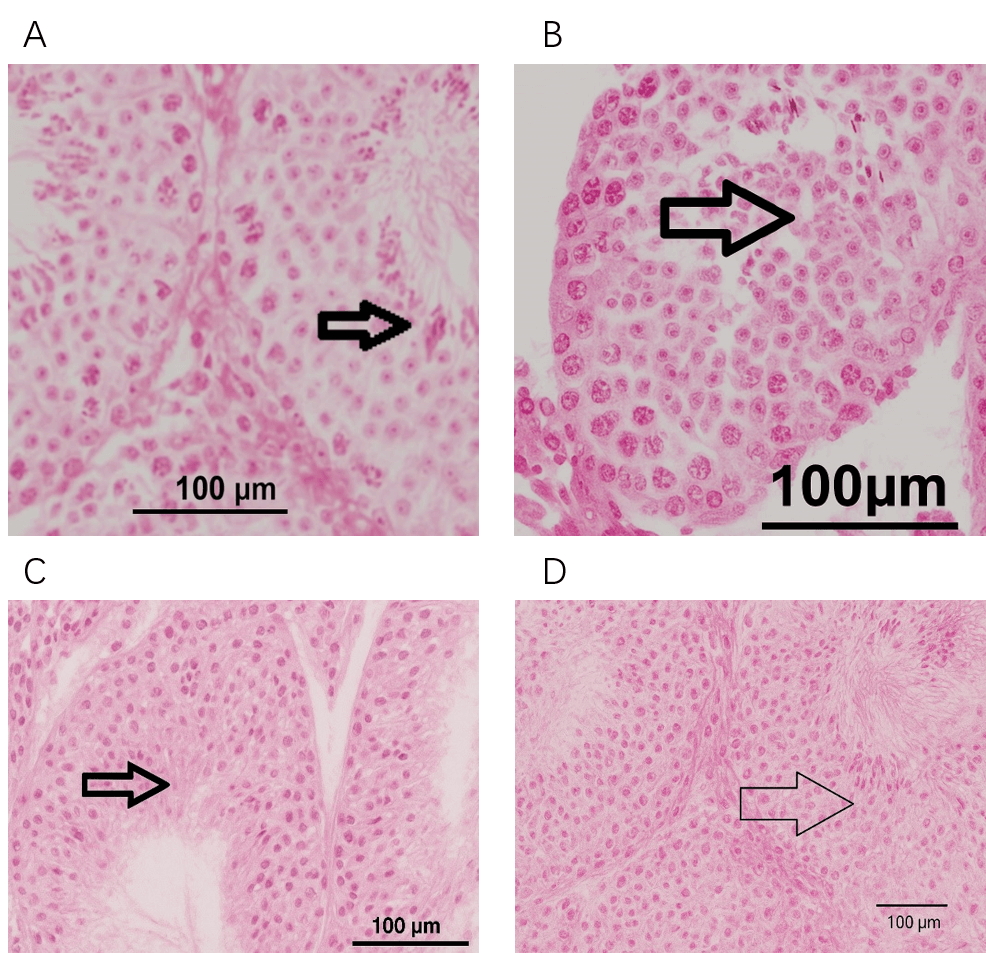

As shown in Fig. 1(A), the histological photomicrograph of the testis tissue

stained with H&E in Group 1 (control group) shows seminiferous tubules with

spermatogonia, spermatocytes, and spermatids (H&E

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Histopathological evaluation of spermatogenesis in testicular biopsies of male albino rabbits. (A) Group I. (B) Group II. (C) Group III. (D) Group IV. A. Group I (control group) shows normal spermatogenesis with some attached spermatozoa in the lumen of the seminiferous tubules. The arrow indicates the mature spermatogenic cells and spermatozoa. B. Group II (Curc group) shows spermatogenesis with an abundance of spermatogenic cells at different stages of maturation with scattered spermatozoa. The arrow depicts the differentiated spermatogenic cells. C. Group III (TAA group) shows a loss of differentiation and maturation of spermatocytes with fewer mature spermatozoa, apoptotic cells, and necrotic sloughs. The arrow points to the apoptotic spermatogenic cells. D. Group IV (TAA + Curc group) shows an improvement in the spermatogenic activity with fewer apoptotic cells and mature spermatozoa. The arrow highlights the spermatozoa and minimal apoptotic cells. Scale bar = 100 µm. Curc, Curcumin; TAA, Thioacetamide.

The findings of the current study reveal that, although there were no significant differences in testosterone levels across the groups, oxidative stress parameters were notably higher in the thioacetamide-treated group (Group III) compared to the other groups. Curcumin treatment, either alone or in combination with thioacetamide, showed a protective effect, enhancing antioxidant levels and mitigating oxidative damage. The histological analysis indicated that Group III experienced significant testicular damage, whereas curcumin treatment in Group IV helped restore spermatogenesis and reduce cellular damage. Overall, curcumin treatment demonstrated potential in mitigating the adverse effects of thioacetamide.

Many pathological conditions can induce germ cell apoptosis, including exposure to toxic substances, heat stress, ionizing radiation, and hormonal depletion [30]. Oxidative stress caused by tissue toxicity causes sperm dysfunction. ROS production must be minimal to maintain the normal capacity and acrosomal reactions in spermatocytes [31]. Meanwhile, efforts have been made to increase fertility; nearly all focus on hormonal management [32]. During normal spermatogenesis, testicular apoptosis is observed in mammals and is believed to be essential for maintaining the balance between Sertoli cells and germ cells [33]. The toxic effects of TAA on various organs are well known and are often used as an inducing agent in experimental models [34]. However, TAA studies on reproductive activity are limited. The protective action of curcumin against oxidative and nitrosative changes in DNA has been demonstrated [35]. These modifications are due to many endogenous and exogenous free radical-producing processes [36]. A previous study demonstrated that curcumin treatment could nearly reverse tramadol-induced toxicity in the testes of male rabbits [37]. The destructive action of TAA was detected in germ cells, which aligns with a study performed by Udagawa et al. [38], who indicated that TAA treatment induces damage to spermatogenesis, making recovery from such damage difficult. However, curcumin successfully repaired the damaged germ cells in the current study, and spermatogenesis was subsequently resumed following curcumin therapy.

In the current study, although the rate of apoptosis in the TAA group was reduced, numerous apoptotic cells remained after treatment. These findings align with those of Tsao et al. [39], who reported that curcumin can significantly improve impaired sperm and testicular function by reducing apoptosis, inflammatory responses, and oxidative stress. Moreover, the current study, as indicated by the JTBS score, detected impaired spermatogenic germ cells in Group III. In this group, the germinal epithelium of the seminiferous tubule showed degeneration, atrophy, sloughing, and apoptotic changes. Moreover, among seminiferous tubules, vascular congestion, edema, and vacuolization were reported in the areas close to the capsule. Furthermore, the testicular histology was efficiently repaired in the groups treated with curcumin (Group IV). A significant reduction in JTBS criteria and MSTD between the TAA-treated group and Groups I, II, and IV. Similarly, Alizadeh et al. [40] reported that curcumin improves semen parameters, oxidative stress, inflammatory biomarkers, and reproductive hormones. The germinal cells have receptors for curcumin, so the direct impact on the cells cannot be ruled out. Conversely, Raices et al. [41] showed that high concentrations of curcumin inhibit cell proliferation, induce cell cycle arrest, reduce cell viability, and activate the apoptotic cell death pathway.

Curcumin is a well-known protector against ROS and has been shown to protect lipids, proteins, and DNA against oxidative damage [42]. Curcumin also stimulates testicular growth, increases testosterone secretion, and positively affects angiogenesis by ameliorating testicular injury [43]. Moreover, curcumin ameliorates oxidative stress in tissues and blood, as indicated by analyses of GSH and MDA levels in the testicular torsion-detorsion model [44].

This study demonstrated that thioacetamide administration resulted in a significant increase in oxidative stress, histological damage to the testicular tissue, and a decline in spermatogenesis. By lowering oxidative stress and enhancing sperm cell maturation, curcumin therapy demonstrated a protective effect and may be used therapeutically to repair testicular damage. Future studies can focus on investigating the mechanisms of action and suitable doses, as these could be used to treat reproductive problems.

The datasets used and analysed during the current study were available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

BHE, AE, TEE and ME designed the research study. OM performed the research. KEH, MMK and EAE provided help and advice on the experiments. BHE, AE, TEE and ME analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. TEE, ME, BMR and IM searched references and edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

All the animals were cared for according to the standard guidelines (3R principles). Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the local animal research Ethics Committee, and the ethics regulations were followed per the national and institutional guidelines (243-8/2024). The ethical review committee of Faculty of Medicine, Al Azhar University, Damietta, Egypt (approval no. IRB 00012264 -19 May 2023).

The authors would like to acknowledge Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, Taif University for funding this work.

The authors would like to acknowledge Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, Taif University for funding this work.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.