1 Key Laboratory of Modern Preparation of TCM, Ministry of Education, Jiangxi University of Chinese Medicine, 330004 Nanchang, Jiangxi, China

2 School of Pharmacy, Anhui University of Chinese Medicine, 230012 Hefei, Anhui, China

3 MOE-Anhui Joint Collaborative Innovation Center for Quality Improvement of Anhui Genuine Chinese Medicinal Materials, 230012 Hefei, Anhui, China

4 Institute of Conservation and Development of Traditional Chinese Medicine Resources, 230012 Hefei, Anhui, China

5 Key Laboratory of Innovative Application of Characteristic Traditional Chinese Medicine Resources in Southwest Anhui Province, Anqing Medical College, 246052 Anqing, Anhui, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

The gastric mucosa is crucial for preventing gastric diseases. Isoschaftoside (Is), isolated from Dendrobium huoshanense, has shown a gastroprotective effect in our previous in vitro study. Thus, this study aimed to evaluate the protective role of Is in an in vivo model of aspirin-triggered gastric injury in mice and explore the underlying mechanisms.

A total of 72 male C57BL/6J mice were classified into control, model, omeprazole (OME, 20 mg/kg), and low- (Is-L, 7.8 mg/kg), medium- (Is-M, 31.2 mg/kg), and high-dose isoschaftoside (Is-H, 93.6 mg/kg) groups. In the model group, aspirin (300 mg/kg) was administered orally for 14 days to induce gastric injury. At the end of the trial, blood sample were taken. Gastric tissues were harvested and prepared for histopathological examination and immunohistochemical identification of mucin 2 (MUC2) expression. ELISA was performed to measure serum levels of interleukin (IL)-6/1β, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1), and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) levels were measured by ELISA. Western blot was used o detect B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2), Bcl-2-associated X protein (Bax), cleaved caspase-9, phospho-phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (p-PI3K), and phospho-protein kinase B (p-AKT) proteins.

Is promoted dose-dependent improvement mucosal structure and reduced inflammation, with high-dose efficacy comparable to that of OME. Furthermore, Is significantly decreased IL-6/1β, and TNF-α levels, increased COX-1 and PGE2, upregulated Bcl-2, downregulated Bax and cleaved-caspase-9, and inhibited PI3K/AKT phosphorylation. Additionally, Is reduced the aspirin-induced upregulation of MUC2 expression, further supporting the role of Is in promoting mucosal repair.

Is alleviates aspirin-induced gastric injury by inhibiting inflammation, regulating apoptosis-related proteins, suppressing the PI3K/AKT pathway, and modulating mucin expression, supporting the potential of using Is as a gastric mucosal protective agent.

Keywords

- isoschaftoside

- gastric mucosal injury

- inflammation

- apoptosis

- mucin

- PI3K/AKT

Peptic ulcer disease, including gastric ulcers, remains a significant global health concern. The gastric mucosa serves as the primary barrier against damaging factors like gastric acid and pepsin. Compromise of this barrier can lead to mucosal injury, inflammation, and ulceration, which may progress to more severe conditions [1, 2].

Despite significant advancements in modern medicine, the use of alternative medicine, such as phytochemicals and Chinese herbal plants, has garnered considerable attention. This is due to their high therapeutic potential, positive health impacts, and fewer side effects [3]. Furthermore, the high cost and limited accessibility of conventional drugs in some regions, alongside interest in natural therapies, motivate the exploration of plant-based alternatives [4, 5].

Dendrobium huoshanense is a perennial medicinal herb of the genus

Dendrobium in the Orchidaceae family, renowned for its

pronounced gastroprotective and therapeutic effects [6, 7, 8]. Key pathological

features of gastric mucosal injury include the overexpression of pro-inflammatory

cytokines (e.g., interleukin (IL)-6/1

In recent years, isoschaftoside has attracted considerable attention due to its promising potential in the intervention of multiple diseases, exhibiting anti-inflammatory [14], anti-aging [15], and antioxidant activities [16], as well as effects against nonalcoholic fatty liver disease [17, 18]. In our previous research, we isolated isoschaftoside from D. huoshanense and found that it demonstrates a gastroprotective effect comparable to that of D. huoshanense itself, effectively protecting gastric mucosal epithelial cells from aspirin-induced injury in vitro [19]. However, the gastroprotective efficacy and underlying mechanisms of this compound in vivo have yet to be comprehensively evaluated and elucidated, necessitating further systematic investigation. Therefore, this investigation aimed to assess the protective effects of isoschaftoside against aspirin-triggered gastric mucosal injury in mice and to investigate its potential mechanisms related to inflammation, apoptosis, the PI3K/AKT pathway, and mucin expression.

We conducted this investigation at Anhui University of Chinese Medicine from June 1, 2023, to March 1, 2025.

Isoschaftoside (purity

C57BL/6J mice (6–7 weeks old, male, 20–25 g) were obtained from Hangzhou

Ziyuan Experimental Animal Technology Co., Ltd. (Zhejiang, China). Mice were kept

under standard specific pathogen-free (SPF) circumstances (humidity 55

The mice were anesthetized via intraperitoneal injection of 3% pentobarbital sodium (No. P3761, Sigma, MO, USA) at a dose of 30 mg/kg prior to blood and stomach tissue collection. The procedure was as follows: pentobarbital sodium powder was dissolved in physiological saline to achieve the appropriate concentration. The mice’s abdominal regions were disinfected with alcohol swabs, and the animals were restrained using forceps. A 1 mL syringe was used to draw the prepared pentobarbital sodium solution, which was then injected intraperitoneally into either side of the lower abdomen. Following the injection, mice were monitored for their physiological responses. Anesthetic effects typically appeared within a few minutes, and the mice entered a state of somnolence.

The HE staining experiment was performed according to standard histological techniques [22]. Following euthanasia by cervical dislocation, the stomach was excised, incised along the greater curvature, and rinsed with physiological saline to remove gastric contents. The mucosa was then laid flat, and comparable regions of gastric tissue were collected from each group. Samples underwent fixing in 4% paraformaldehyde (No. 60536ES60, Yeasen, Shanghai, China), dehydrating, embedding in paraffin, sectioning at 5 µm thickness, and staining with HE. Histological evaluation was conducted using Olympus CX23 microscopy (Tokyo, Japan), and images were acquired for analysis.

Immunohistochemistry was performed as previously described [23].

Paraffin-embedded gastric tissue slices were dewaxed and exposed to antigen

retrieval by heating in antigen retrieval solution. A 10-min blockage of

endogenous peroxidase activity was conducted with 3% H2O2 (No. 216763,

Sigma, MO, USA) at room temperature. An incubation of the slices was then

conducted with anti-MUC2 antibody (ab272692, 1:200, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) overnight at 4

°C, then with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody (ZB-2301, 1:20000 dilution, Zsbio, Beijing, China)

at 37 °C for 30 min. HRP-conjugated streptavidin was subsequently

applied for 30 min at 37 °C. Staining was visualized with

diaminobenzidine (DAB) (No. YT8204, ITTABIO, Beijing, China), followed by

counterstaining with hematoxylin (No. ZY-6144, ZYBio, Shanghai, China),

dehydrating through graded ethanol (No. 10009218, Sinopharm, Shanghai, China),

clearing in xylene (No. 10023428, Sinopharm, Shanghai, China), mounting, and

examining microscopically. For negative controls, the primary antibody was

omitted. Given that MUC2 is well-known for its responsive overexpression to

repair the gastric mucosa under injury [13], gastric tissue damaged by aspirin

was employed as a positive control. Morphometric analysis was performed by

capturing five random fields/section at 200

For serum collection, the peri-oral hair was trimmed, and the eyeballs were

gently enucleated following retro-orbital pressure with ophthalmic forceps. The

collection of blood samples was conducted in 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes,

allowed to clot at room temperature for 30 min, and centrifugation was conducted

at 3000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C for serum separation. ELISA kits were

equilibrated to room temperature prior to use, and all procedures (dilution,

sample addition, incubation, washing, chromogenic reaction, termination) were

conducted as per the manufacturer’s guidelines. Standard curves were created to

quantify serum concentrations of IL-6/1

Protein expression analysis was performed using a standard Western blotting protocol [24]. Processed gastric tissue samples were lysed on ice in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer containing phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) (No. MA0001, Meilunbio, Dalian, Liaoning, China) for 30 min, and protein levels were detected via a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay kit (No. B5001, Land Bridge Technology, Beijing, China). Equal protein quantities were exposed to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (No. P1200-25T, Solarbio Science & Technology, Beijing, China) and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (No. IPVH00010, Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). A 2-h blockage of membranes was conducted with 5% (w/v) non-fat dry milk at 25 °C, then an incubation was conducted with primary antibodies for 2 h, then with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h. The Amersham Imager 600 imaging system (GE Health, Chicago, IL, USA) and enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagent (No. BL520A, Biosharp, Hefei, Anhui, China) were utilized for detection. Densitometric analysis of PI3K, AKT, caspase-9, BCL-2, and BAX protein bands was conducted via ImageJ software (v1.53, NIH, USA). Primary antibodies include Bax (50599-2-1g, 1:2000 dilution, Proteintech, IL, USA), Bcl-2 (ab32124, 1:1000 dilution, abcam, Cambridge, UK), cleaved-casepase-9 (9509, 1:1000 dilution, CST, MA, USA), procasepase-9 (ab32539, 1:5000 dilution, abcam, Cambridge, UK), PI3K (ab86714, 1:1000 dilution, abcam, Cambridge, UK), p-PI3K (ab182651, 1:1000 dilution, abcam, Cambridge, UK), AKT (4691s, 1:1000 dilution, CST, MA, USA), p-AKT (4060s, 1:2000 dilution, CST, MA, USA), and GAPDH (TA-08, 1:2000 dilution, Zsbio, Beijing, China).

SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was utilized to conduct statistical

analysis, and data are expressed as mean

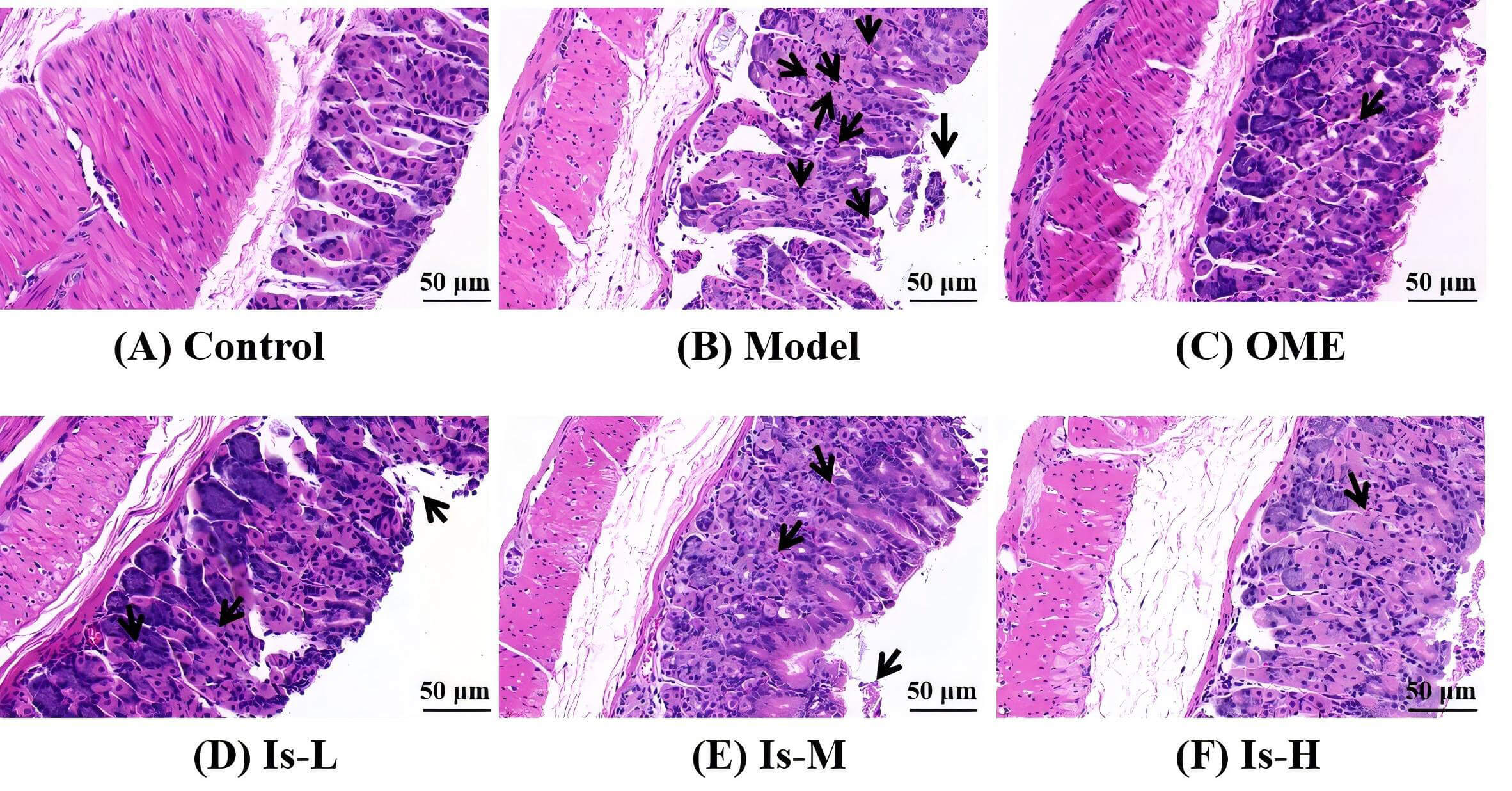

HE staining of gastric tissues showed that mice in the Control group exhibited intact gastric mucosa with well-preserved architecture, closely arranged glands, and absence of mucosal bleeding or edema. In contrast, the Model group displayed disorganized and sparse glandular arrangement, partial loss of mucosal epithelial cells, and marked infiltration of inflammatory cells. Compared to the Model group, mice in the OME group demonstrated relatively preserved mucosal structure, more regular glandular organization, and reduced inflammatory cell infiltration. Isoschaftoside treatment produced a dose-dependent improvement, evidenced by increasingly regular and distinct glandular arrangement as the dose increased, along with decreased inflammatory cell infiltration (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining of mouse gastric mucosal tissue sections. (A) Control, the gastric mucosa is intact with a well-preserved architecture, and the glands are tightly packed and well-aligned. (B) Model, the gastric mucosal structure is severely damaged, accompanied by marked inflammatory cell infiltration. (C) Omeprazole (OME) (20 mg/kg), the gastric mucosal structure is relatively intact with fairly orderly arranged glands and shows only minor inflammatory cell infiltration. (D) Low-dose isoschaftoside (Is-L) (7.8 mg/kg). (E) Medium-dose isoschaftoside (Is-M) (31.2 mg/kg). (F) High-dose isoschaftoside (Is-H) (93.6 mg/kg), with increasing Is concentration, the glands became progressively more organized and distinct, and the inflammatory cell infiltration was reduced. Scale bar, 50 µm. The black arrows indicate areas of inflammatory cell infiltration or injury.

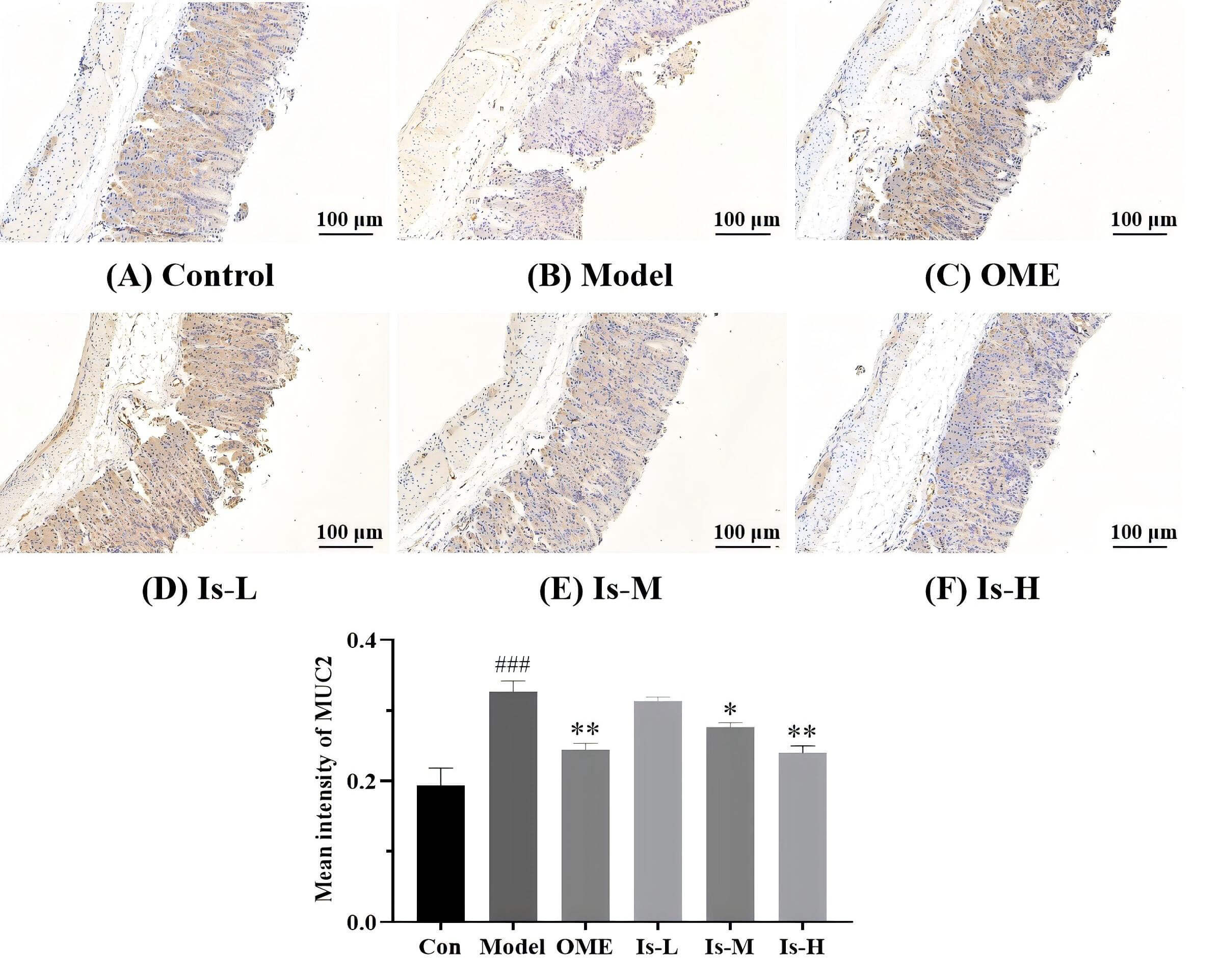

To elucidate the protective action of isoschaftoside on the gastric mucosa, MUC2

expression was examined by immunohistochemistry. The outcomes illustrated that

MUC2 expression in the gastric tissue of mice in the Model group was

significantly higher than the Control group (p

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Detection of mucin 2 (MUC2) expression in mouse gastric mucosa

by immunohistochemistry. (A) Control, shows weak positive staining. (B) Model,

exhibits strong positive staining for MUC2, indicating a significant

upregulation. (C) OME (20 mg/kg), displays moderate positive staining for MUC2.

(D) Is-L (7.8 mg/kg), strong positive staining. (E) Is-M (31.2 mg/kg) and (F)

Is-H (93.6 mg/kg), moderate positive staining, suggesting a partial reversal of

MUC2 overexpression induced in the Model group. Con represent Control group.

###p

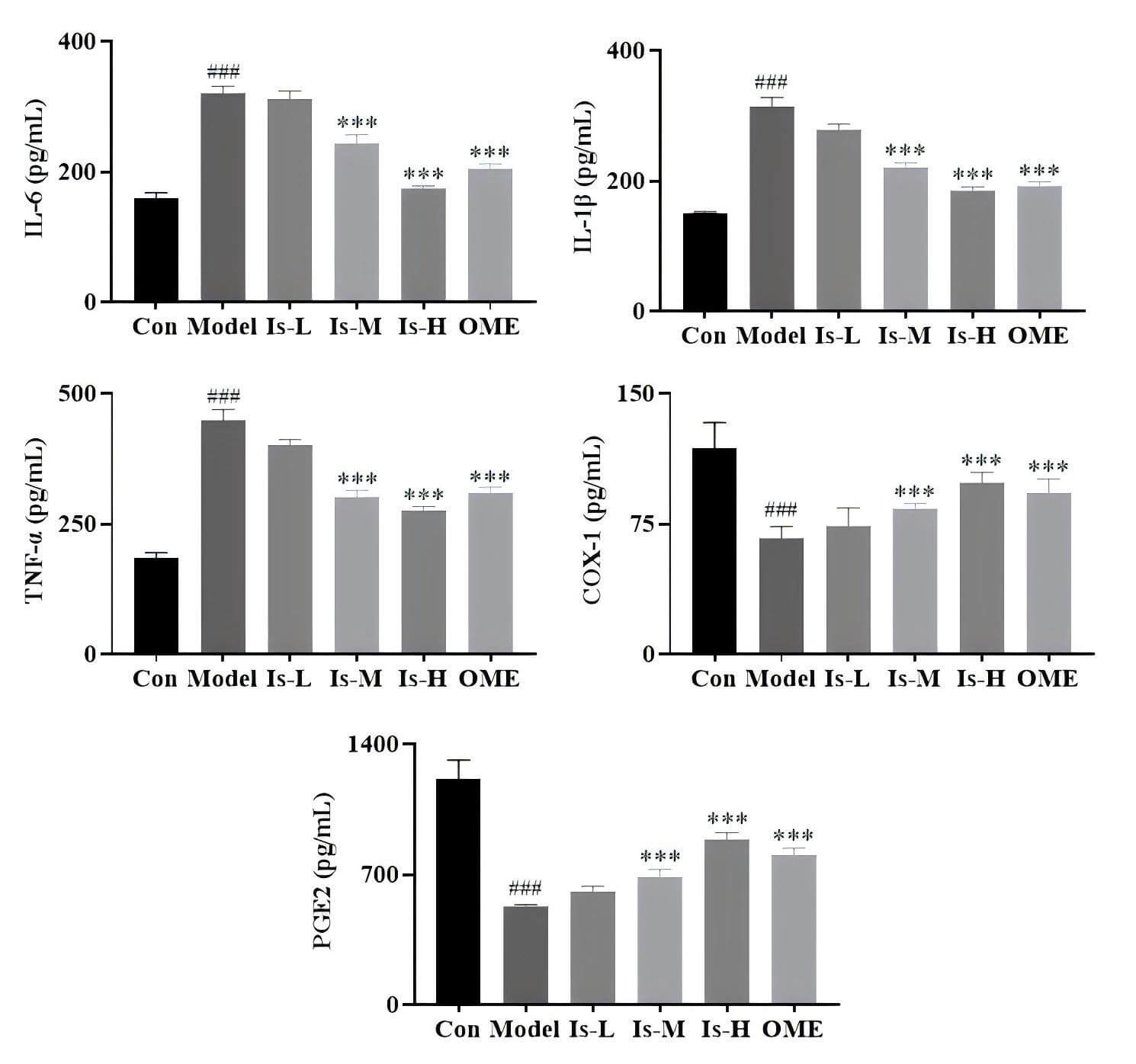

To assess systemic inflammatory responses, serum cytokine levels were measured

in mice. Compared with the Control group, mice in the Model group exhibited

significantly elevated concentrations of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6,

IL-1

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

ELISA detection of IL-6, IL-1

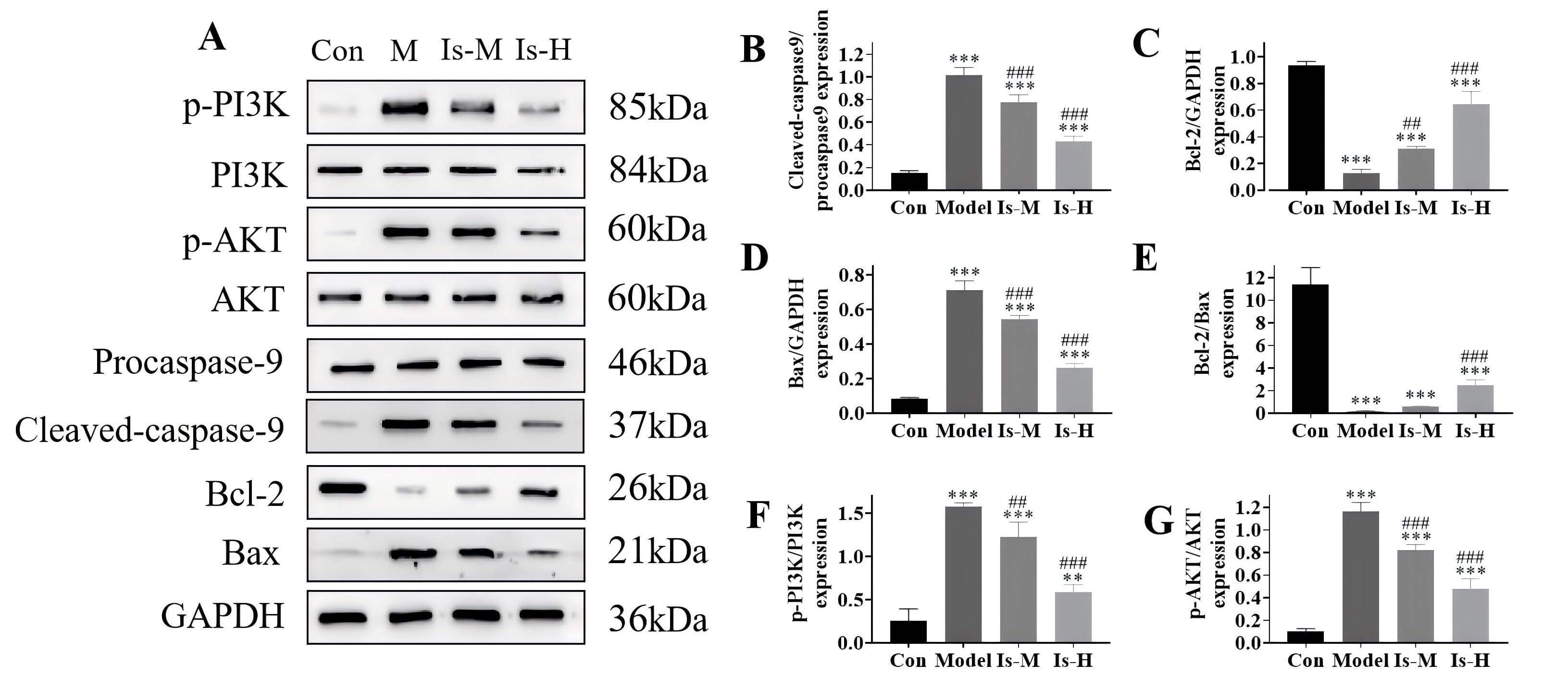

The levels of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 and the pro-apoptotic proteins

Bax and caspase-9 were investigated. Following treatment with isoschaftoside, it

was observed that this compound could counteract the aspirin-induced decrease in

Bcl-2 expression (Is-M, p

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

The isoschaftoside effect on the expression of correlated

proteins. (A) Western blot analysis. (B–G) Protein expression levels. Con

represent Control group. **p

The regulatory effects of isoschaftoside on PI3K/AKT pathway-correlated proteins

p-PI3K and p-AKT were examined. The outcomes indicated that the p-PI3K and p-AKT

levels increased following aspirin-induced injury (p

Herein, a mouse model of aspirin-triggered gastric mucosal injury was created to systematically assess the protective actions and underlying mechanisms of isoschaftoside on the gastric mucosa. HE staining demonstrated that isoschaftoside significantly improved gastric mucosal architecture and reduced inflammatory cell infiltration dose-dependently manner. Notably, the protective effect observed with high-dose isoschaftoside was comparable to that of the positive control, omeprazole. These findings indicate that isoschaftoside confers substantial gastric mucosal protection, consistent with the traditional medicinal properties attributed to D. huoshanense, its source herb, and provide morphological evidence to support further development of isoschaftoside as a gastroprotective agent.

Regarding inflammatory mediators, serum levels of IL-6/1

Previous studies have shown that traditional Chinese medicines can ameliorate gastric ulcers by controlling the PI3K/AKT pathway, thereby exerting anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anti-apoptotic effects [27, 28]. Accordingly, the present study investigated alterations in apoptosis-correlated proteins (BCL-2, BAX, cleaved caspase-9) and the PI3K/AKT pathway. Western blot analysis revealed that isoschaftoside dose-dependently elevated the anti-apoptotic protein BCL-2, reduced the pro-apoptotic proteins BAX and cleaved caspase-9, and significantly inhibited stimulation of the PI3K/AKT pathway. These data illustrate that isoschaftoside may exert its gastroprotective effects through inhibition of the PI3K/AKT axis and attenuation of downstream apoptotic signaling cascades. To date, such a mechanism has not been widely reported for isoschaftoside, and our findings provide a novel perspective on its mode of action.

The findings of this study highlight the potential of isoschaftoside as a valuable natural product for the management or prevention of gastric mucosal injury, particularly in scenarios involving NSAID use like aspirin. It could be developed as a complementary agent to reduce the gastrointestinal side effects linked to long-term NSAID therapy.

Despite the promising results obtained in this study, several limitations should

be noted. All in vivo experiments were conducted exclusively in male

mice, precluding assessment of sex-based differences in pharmacological effects.

Mechanistic investigations focused primarily on the PI3K/AKT pathway and

apoptosis-correlated proteins, without exploring involvement of other pathways

such as NF-

In summary, isoschaftoside markedly attenuates aspirin-induced gastric mucosal injury in mice, potentially through inhibition of inflammatory responses, modulation of apoptosis-related protein expression, and blockade of PI3K/AKT pathway activation. Its efficacy is comparable to the clinical drug omeprazole at a high dose. This study provides experimental support for the innovation and development of isoschaftoside as a prospective gastric mucosal protective agent in high-risk individuals, such as chronic NSAID users, and lays the groundwork for its further development and application.

Further materials related to this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

PY, DP and PZ designed the research study. JH and JS performed the research. QW and LH provided help and advice on the animal experiments. JH, JS and PZ drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The animal research was approved by the Experimental Animal Ethics Committee of Anhui University of Chinese Medicine No. AHUCM-mouse-2023169. It was followed by the 3R principles. All animals were handled with human care during the experiment and all treatments were strictly conducted under the supervision of the Experimental Animal Ethics Committee at Anhui University of Chinese Medicine.

Not applicable.

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82304881), the Open Fund Project of Key Laboratory of Modern Preparation of TCM, Ministry of Education, Jiangxi University of Chinese Medicine (No. Zdsys-202305), the Major Special Science and Technology Project of Anhui Province (No. 202303a07020005) and Key Natural Science Research Projects in Anhui Universities (No. 2022AH050484, 2022AH040323).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.