1 Pharmaceutical College, Guangxi Medical University, 530021 Nanning, Guangxi, China

2 Key Laboratory of Biological Molecular Medicine Research (Guangxi Medical University), Education Department of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, 530021 Nanning, Guangxi, China

Abstract

The misuse of antibiotics has led to an increase in the existence of superbugs, with a concurrent rise in drug resistance rates. Therefore, given the current situation, there is an urgent need to identify new antimicrobial agents and develop novel therapeutic strategies. Recently, antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), a newly discovered class of antimicrobial substances, have emerged as small molecular peptide chains exhibiting broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity. Meanwhile, over the past few decades, extensive research and the application of antimicrobial peptides have led to a surge in studies investigating the molecular structure, design, and modifications to the synthesis of AMPs. Initially, this paper delineates the sources, structures, and mechanisms of action of AMPs, providing a foundation for subsequent studies. Subsequently, this study focuses on the design and synthetic modification of the molecular structure of AMPs, including modifications through chemical synthesis methods and improvements via genetic engineering and biotechnological approaches, to enhance the associated antimicrobial activity, stability, and reduce biotoxicity. This review serves as a reference for further research into AMP design and synthesis.

Keywords

- antimicrobial peptides

- peptide structures

- antibacterial mechanisms

- chemical modification

In recent years, antimicrobial peptides have garnered substantial interest as a crucial component of the immune defense system. These peptides exert their effects by binding to bacterial cell membranes which induces membrane disruption, consequently curbing bacterial growth and proliferation effectively [1].

Over the past few decades, researchers have optimized the sequence and structure

of peptide segments with the aid of computer-aided technologies such as molecular

docking. They have enhanced the physiological stability of antimicrobial peptides

(AMPs) by regulating secondary structures including

Currently, the application of AMPs still faces three core challenges: the balance between selectivity and toxicity of them, insufficient in vivo biological stability, and the cost of large-scale production. To address these challenges, future research needs to achieve breakthroughs in three aspects: deepening the study of molecular mechanisms of action, establishing an integrated “design-synthesis-screening” platform.

AMPs are small-molecule proteins widely present in organisms. It typically composed of 10–50 amino acids, and are renowned for their broad-spectrum antibacterial properties. These peptides are ubiquitously present across various forms of life, including humans, animals, plants, and microorganisms, and serve as key substances for host immune defense. On the other hand, AMPs possess amphipathic and positively charged characteristics. This unique property enables AMPs to be easily integrated into cell membranes or penetrate through cell membranes into the cytoplasm, thereby exhibiting excellent activity against exogenous pathogens.

In the 1970s, Swedish scientist Boman and his team [2] made a groundbreaking discovery of the first antibacterial polypeptide in Hyalophora cecropia, dubbing it Cecropin. Since this seminal finding, an increasing number of novel AMPs have been identified annually. The Antimicrobial Peptides Database (Antimicrobial Peptide Database, APD3) updated in January 2024, encompasses a comprehensive catalog of 3146 AMPs derived from 6 domains of life (383 from bacteriocins or peptide antibiotics isolated or predicted from bacteria, 5 from archaea, 8 from protists, 29 from fungi, 250 from plants, and 2463 from animals, including genomic predictions and some synthetic peptides). Among these, Plant-derived antimicrobial peptides are an interesting and promising class of compounds that include several substances with antibacterial and antifungal properties, such as defensins, albumin, glycine-rich proteins, thiols, cyclic peptides, and napoleon peptides [3, 4].

While antimicrobial peptides of animal origin predominate, plant-derived and human-derived peptides also hold significant research value. Notably, amphibian skin serves as a rich reservoir of natural antimicrobial peptides. For instance, Bombesin, an antimicrobial peptide produced by amphibians, was initially isolated from the skin of the European Bombesin, and exhibits potent antibacterial properties [5]. In humans, LL-37 is the sole Cathelicidin antibacterial peptide present. Human-derived antimicrobial peptides are encoded and synthesized by human genes and play an integral role in the innate immune system while being less likely to provoke autoimmunity or toxicity [6]. In addition to these natural sources, researchers can employ chemical synthesis and computer-aided genetic engineering to design and encode gene sequences for the expression and production of antimicrobial peptides. Through synthesis, peptides with enhanced stability and antibacterial activity can offer a new avenue for the development and medical application of antibacterial drugs.

The dual-sensitive antimicrobial peptide pHly-1 is engineered from the natural spider toxin peptide Lycosin-I. Through strategies such as lysine (Lys) residue substitution and histidine (His) residue addition on the template peptide, the optimization of properties including charge, hydrophobicity, and spatial structure has been successfully achieved. It exhibits excellent activity against various bacterial strains such as Streptococcus mutans, demonstrating promising prospects for caries prevention and treatment.

In an acidic environment, pHly-1 exerts reliable antimicrobial activity against

Streptococcus mutans primarily by disrupting the bacterial cell membrane and can

inhibit biofilm formation. Under normal physiological conditions, however, pHly-1

adopts a

Antimicrobial peptides are typically cationic and short in length, distinguished by the amphiphilic properties arising from the combination of hydrophobic amino acids and those carrying a net positive charge [12]. The primary structure of these peptides, which refers to the linear sequence of amino acids, exhibits a significant degree of diversity and complexity. The composition and sequence of amino acids within this primary structure may either be uniform or varied. It is the specific arrangement of amino acids in the primary structure that dictates the peptide’s spatial configuration, that is, its three-dimensional structure in space, which in turn governs its biological activity and antibacterial efficacy.

Building on the diversity of the primary structure, the secondary structures of

antimicrobial peptides are intricate and diverse, yet they can be categorized

into four main types:

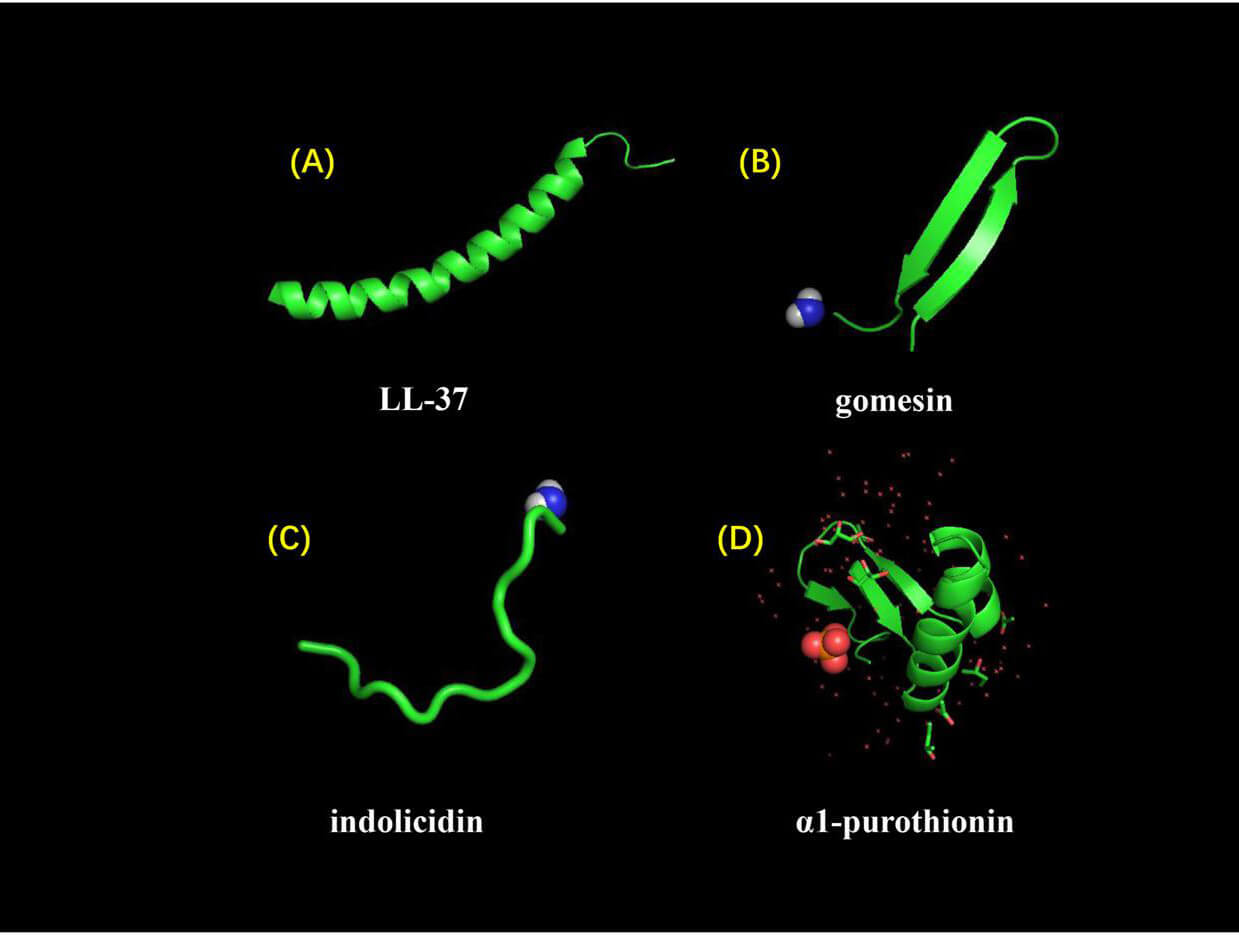

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Secondary Structure Classification of Antimicrobial Peptides.

According to the classification of secondary structure antibacterial peptides

(A) LL-37,

The

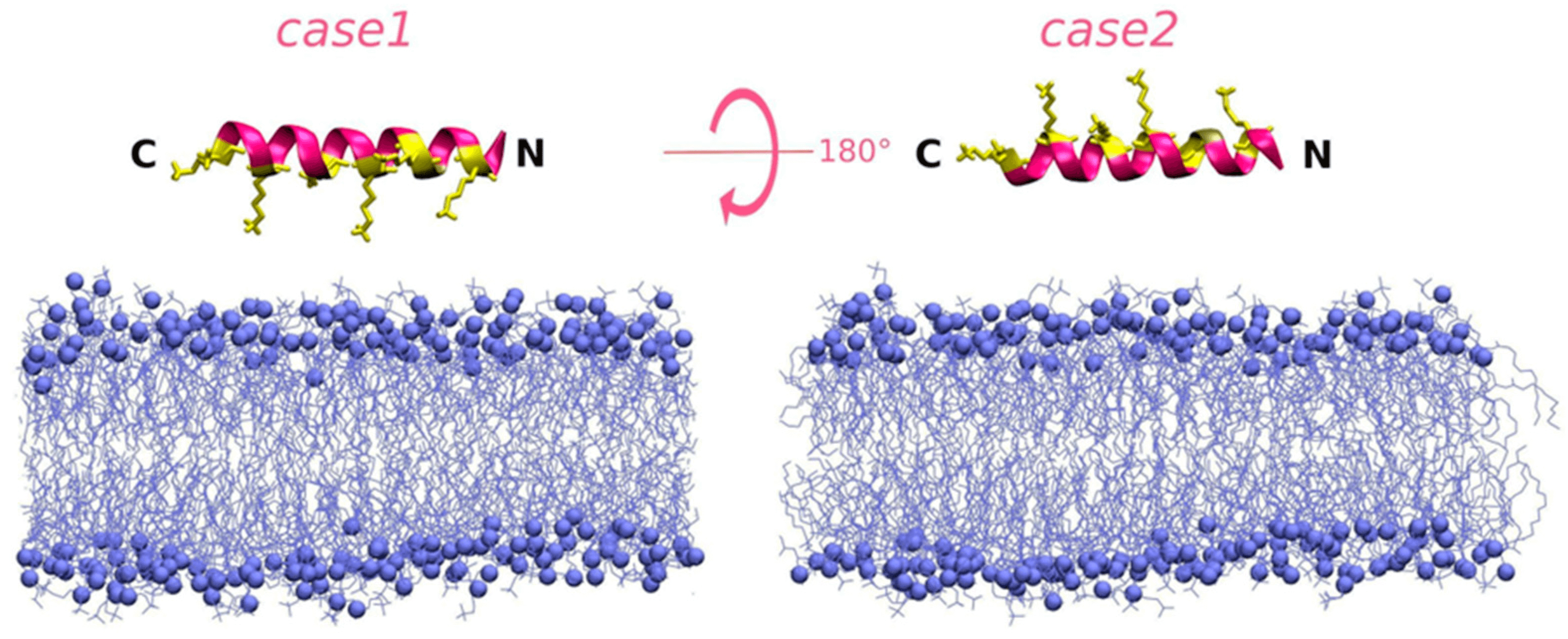

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Representation of the initial conditions for the case1 and case2 simulation runs of diPGLa-H (KIAKVALKALKIAKVALKAL) interacting with the DLPC membrane. It is taken at the 0 ns simulation time after an energy minimization procedure carried out on the peptide structure defined by the QUARK output [14]. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [14] Copyright (2020) Front Microbiol.

The tertiary and quaternary structures of antimicrobial peptides exhibit a spectrum of diversity and are influenced by environmental factors. Within specific hydrophobic milieus, the hydrophobic segments of antimicrobial peptides can assemble into stable tertiary or quaternary spatial configurations [12]. These structures arise from the hydrophobic interactions among amino acids along the antimicrobial peptide chains within a hydrophobic context. Such interactions propel the hydrophobic amino acids to segregate from aqueous environments, thereby facilitating the formation of stable, regular or irregular spatial architectures. These spatial architectures are typically consolidated by an array of hydrogen bonds, van der Waals forces, and other non-covalent interactions, which together contribute to their stability and functionality.

The precise mechanism underlying the action of antimicrobial peptides remains an area of active investigation, with the antibacterial mechanism being specific to individual or a limited number of antimicrobial peptides. Currently, no single mechanism of action can comprehensively elucidate the function of all antimicrobial peptides. This paper primarily addresses three aspects of the antibacterial mechanism: Firstly, the direct bactericidal effect, which involves the disruption of the cell membrane’s integrity through interaction with the microbial cell membrane, leading to cell death. Secondly, the interference with the synthesis of nucleic acids and proteins, where antibacterial substances penetrate the cell and interact with nucleic acids and proteins, thereby inhibiting their synthesis and preventing bacteria from surviving and reproducing normally. Finally, by leveraging the mechanism of antimicrobial peptides in inhibiting biofilm formation, the formation of biofilms is suppressed.

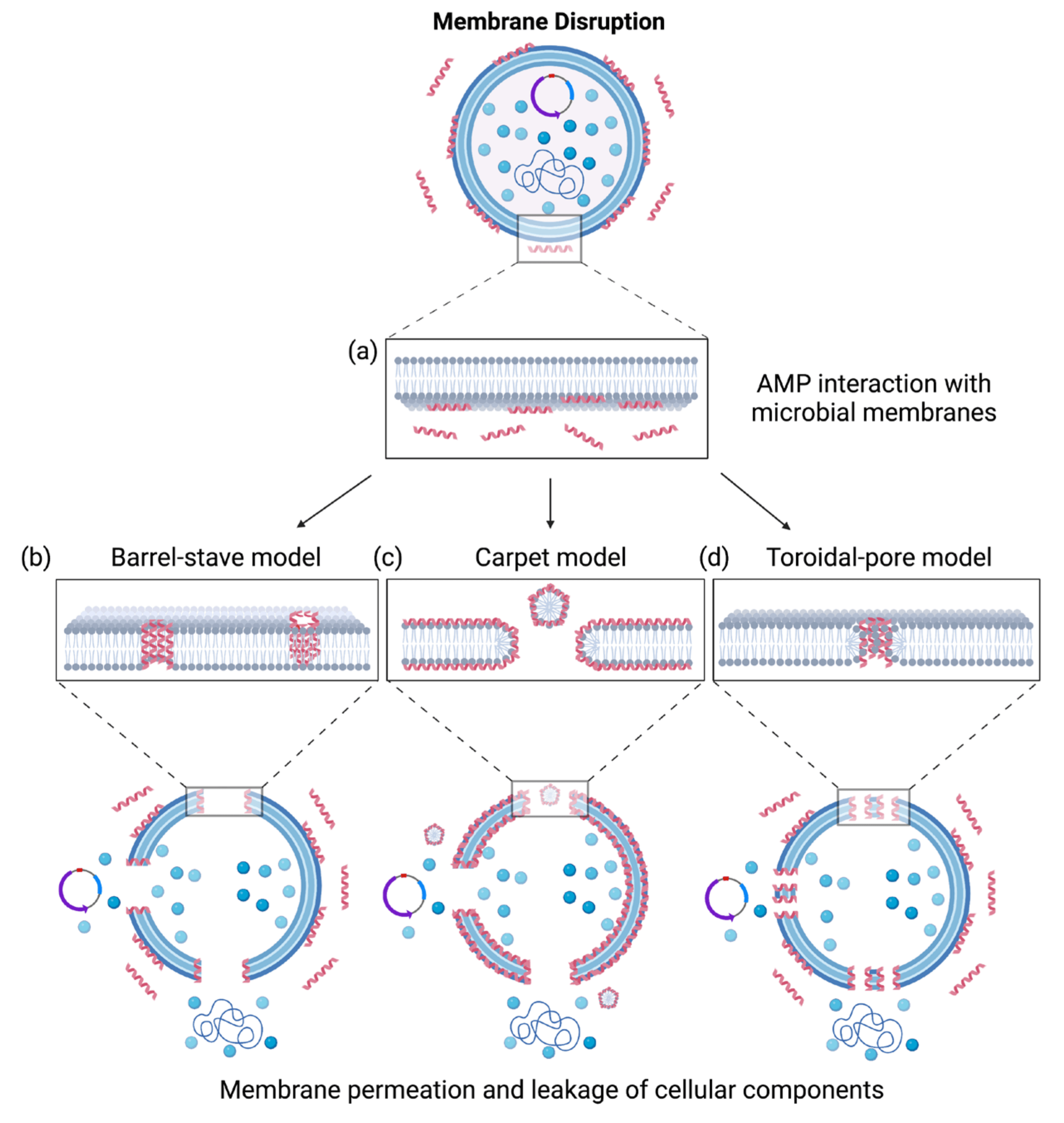

Scientists employ a variety of techniques to elucidate the mechanism of action of antimicrobial peptides on cell membranes, including microscope technology, ion channel technology, X-ray diffraction, Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR), circular dichroism and directional circular dichroism. AMPs primarily interact with the negative charges present on cell membrane surface through their own positive charges, leading to a conformational change in the AMPs. By inserting into the cell membrane and forming channels, AMPs disrupt the membrane structure, causing rapid cell death and exerting their antibacterial effects. Antimicrobial peptides can penetrate the cell membrane, which have three predominant models of AMP penetration into the cell membrane: the toroidal pore model, the barrel-stave model and the carpet model (Fig. 3) [18].

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

AMPs interact with microbial membranes and their associated mechanisms of action. (a) AMP interaction with microbial membranes. (b) Barrel-stave model. (c) Carpet model (d) Toroidal-pore model [18]. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [18] Copyright (2023) Microorganisms.

Most AMPs that follow the barrel-stave model carry a net positive charges and

integrate vertically into the cell membrane as monomers or oligomers via

electrostatic interactions. These peptides insert their hydrophobic segments into

the phospholipid bilayer towards the interior of the membrane, while their

hydrophilic segments face the barrel wall, thus forming a hydrophilic,

barrel-shaped ion channel. As the concentration of AMP molecules increases, the

ion channels expand correspondingly, causing the leakage of cellular contents,

which ultimately results in cell disintegration and demise. For instance, Ctx-Ha,

an antimicrobial peptide derived from frog skin secretions, exerts its biological

activity based on the barrel-stave model [19]. Protegrin-1 (PG-1) is a

The toroidal pore model shares structural similarities with the barrel-stave model. When AMP is inserted into the membrane, phospholipids continuously bend from leaflet to the other, forming a pore surrounded by phospholipid head groups and peptide molecules [21]. However, a key distinction exists in the toroidal pore model: the hydrophobic regions of AMPs interact with the lipid layer of the bacterial cell membrane, and encircle pores that contain the hydrophilic segments of the peptides, thereby forming a ring-shaped transmembrane porous channel. This channel disrupts the integrity and permeability of the bacterial cell membrane, impairs essential cellular functions, and utimately culminates in bacterial death. Yoneyama et al. [22] initially proposed toroidal pore model, and subsequent have demonstrated that lactin can form toroidal pores by interacting with phospholipids on the cell membrane of Gram-positive bacteria (G+), ultimately leading to bacterial demise.

In the carpet model, AMPs configure a structure analogous to a “blanket”, aligning parallel to the cell membrane surface. These peptides interact with phospholipid molecules on the membrane’s exterior, thereby altering the surface tension and inducing the formation of transient pores. Consequently, this results in membrane damage and the leakage of intracellular contents, ultimately culminating in cell death [23]. A well-characterized example is the human LL-37, which exerts its antibacterial effect based on the carpet model.

While the disruption of target cell membrane’s integrity is a potent antimicrobial strategy, it is not invariably lethal, as evidenced by the survival of some microorganisms post-membrane leakage. This suggests that membrane damage alone is insufficient to ensure cell death. Furthermore, AMPs can exert their antimicrobial effects by binding to intracellular targets, such as cellular DNA to disrupt gene expression or bacterial proteins to inhibit growth and reproduction [24]. Di Somma et al. [25] investigated the interaction between the antimicrobial peptide temporrin L and Escherichia coli, observing that temporin L damages E. coli cell division by interacting with FtsZ protein and divisome complex. The interaction with AMPs results in the formation of elongated cell filaments, ultimately preventing cell division. In non-membrane-based mechanism, AMPs gain entry into the cell by direct osmosis or endocytosis. Once internailized, AMPs may target various biological processes, including nucleic acid transcription, translation and protein folding by inhibiting the activity of related enzymes or molecules.

Biofilms consist of microbial communities that adhere to biological or abiotic surfaces and are encapsulated by bacterial extracellular macromolecules. The mechanisms by which antimicrobial peptides inhibit biofilm formation include the following: inhibition of the bacterial quorum sensing system, inhibition of bacterial adhesion or induction of the dispersion of cell aggregates, attenuation of extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) production, and downregulation of the expression of binding protein transport genes [26, 27, 28, 29].

In conclusion, the mechanisms underlying the antibacterial action of AMPs are highly intricate. While researchers have posited a multitude of mechanisms for various antibacterial peptides, it is imperative to consider a spectrum of potential antibacterial mechanisms during investigations to achieve a holistic understanding of their effects. Concurrently, in the quest for novel antimicrobial peptides, attention should be directed towards their multifunctional mechanisms to enhance their efficacy against a broad spectrum of microorganisms.

AMPs, integral components of the innate immune system, are widely involved in the barrier defense of life and the innate immune response [30], exhibit broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity and a variety of biological functions [31]. As shown in Table 1, it presents the molecular structure, synthesis methods and pharmacological effects of AMP. Nonetheless, significant challenges persist in their clinical application, including cytotoxicity [32], short half-life and high production costs. Structure dictates function: the size, charge, residue composition, conformation, helicity, hydrophobicity, and amphiphilicity of AMPs all determine the potency of their antimicrobial activity [33, 34]. Thus, the antibacterial efficacy of AMPs is contingent upon their structural characteristics. Consequently, the structural modification of AMPs to enhance their antibacterial potency while reducing cytotoxicity has became a central theme in current investigative efforts.

| Category | Core content |

| Molecular structure | Basic property: Short-chain cationic peptide, integral component of the innate immune system. |

| Activity determinants: Molecular size, net charge, amino acid composition, conformation ( | |

| Synthesis methods | Chemical synthesis: Solid-phase synthesis, liquid-phase synthesis, amino acid substitution, sequence truncation, hybrid analog modification. |

| Bioengineering: Genetic engineering, CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene editing (for activity enhancement). | |

| AI-assisted design: Computational screening (e.g., variational inference autoencoder) for high-throughput discovery. | |

| Hybrid peptides. | |

| Modification of Template Peptides. | |

| Pharmacological effects | Direct antimicrobial: Broad-spectrum activity against pathogens, membrane pore formation, low tendency for inducing drug resistance (effective against multidrug-resistant bacteria). |

| Immunomodulation: Mediates biological barrier defense, regulates innate immune responses. | |

| Application potential: Therapeutic candidate for infectious diseases, optimized to reduce cytotoxicity. |

To address the challenges associated with AMPs synthesis, researchers have devised an array of strategies, encompassing solid-phase synthesis, liquid-phase synthesis and self-assembly techniques. Moreover, genetic engineering technology is extensively utilized in the design and modification of antimicrobial peptides. Among these approaches, amino acid residue substitution stands out as a prevalent molecular modification method for AMPs. By altering the gene sequence, the activity and specificity of AMPs can be significantly enhanced. The method of amino acid residue replacement is noted for its high efficiency and simplicity, facilitating the design of AMP molecules and screening of their activity [35].

With the advancement of artificial intelligence technology, computers have become increasingly pivotal in the research of antimicrobial peptides. Utilizing software tools to modify the active regions of AMPs facilitates high-throughput and efficient screening, thereby enabling large-scale identification of more potent AMP molecules. For instance, Das et al. [36] employed computer-assisted learning to analyze nearly 1.7 million peptides in the Universal Protein Resource (UPR) using variational inference autoencoder. These peptides were subsequently categorized into two categories based on their antimicrobial activity. By constructing a “classifier” for peptide antimicrobial potency, they identified two novel AMPs (YI12 and FK13) with enhanced activity. The findings indicated that the half hemolysis values (HCso) and median lethal doses (LDs) of these peptides were significantly higher than the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values, with LDs values comparable to those of the antibiotic polycolistin B.

Gene editing technology, an emerging field, has been widely applied across various domains. The CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing system enables precise DNA modifications, representing a crucial method in contemporary gene editing [37]. In the realm of AMPs, CRISPR-Cas9 technology can be harnessed to edit and engineer genes encoding AMPs, thereby enhancing their activity and efficacy. This approach facilitates the design of AMPs with higher activity and specificity, boosting their bactericidal potency and broad-spectrum antibacterial capabilities. Furthermore, CRISPR-Cas9 technology can be employed to investigate the interactions among AMPs, proteins, cell membranes, and bacterial resistance mechanisms, thereby deepening our understanding of the mechanism underlying AMP function. In conclusion, CRISPR-Cas9 technology holds substantial promise and possesses vast potential for research in AMPs. Whether for designing more effective AMP molecules or the elucidating their antimicrobial mechanisms, this technology can make a positive contribution to the advancement of this field.

Another effective approach is the de novo design and synthesis of AMPs via

hybridization technology. For instance, the combination of AMPs with low toxicity

and moderate activity and those exhibiting high activity but relatively higher

toxicity enables the development of novel chimeric AMPs that possess both high

antibacterial activity and low toxicity [38]. Researchers have fused the

N-terminal

On the other hand, AMPs provide a simple and effective approach for the development of novel antibacterial drugs through the regulation of physicochemical determinants, modification of truncated and hybrid analogs, and redesign via amino acid substitution of natural peptide sequences. For instance, the antibacterial activity of GI24, a 24-residue truncated peptide of PMAP-36, is not affected by the truncation of the C-terminal region [41]. The truncation of LL-37, based on the amino acid composition and 3D structure, which retains its antibacterial activity while losing its side effects [42].

AMPs are short cationic peptides with directly antimicrobial and

immunomodulatory activities as multifunctional mediators of innate immune

responses, which have a promising application in the treatment of infectious

diseases. Short peptides can have their biophysical properties improved through

chemical stabilization. In 2018, Yuan et al. [43] used template strategy

to design and synthesize a series of conformationally restricted AMPs with either

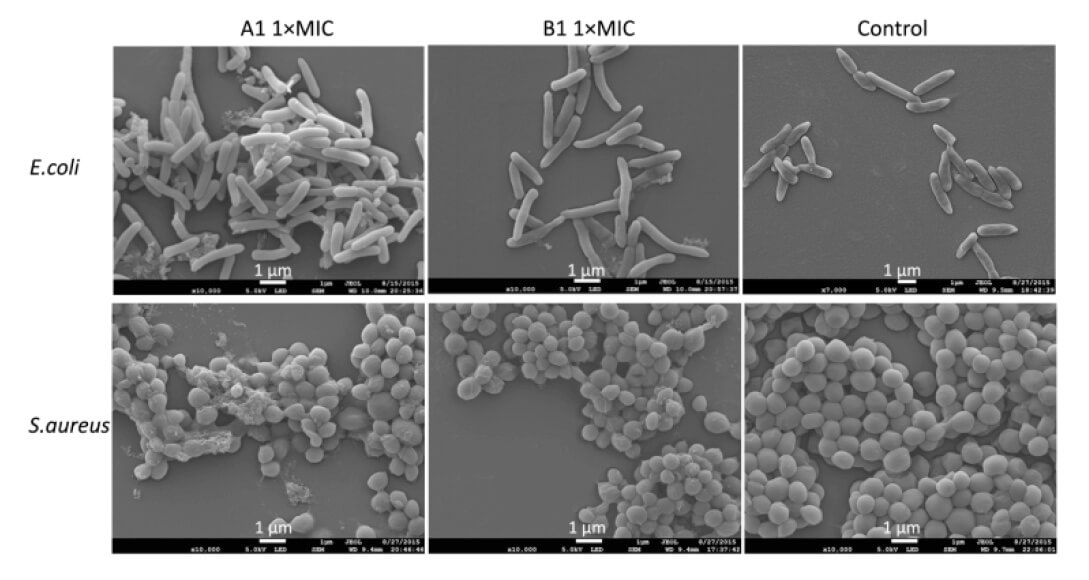

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

E. coli (above) and S. aureus (below) were observed by SEM after

incubation with AMP-A1 and B1 at 1

AMPs also exhibit undesirable properties including hemolytic activity toward human red blood cells, sensitivity to protease, salt and serum, and high production cost which impede their development as therapeutic agents [44]. However, optimization of sequences or modification of AMPs can enhance their antibacterial efficacy while reducing cytotoxicity, thereby overcoming existing obstacles and accelerating the development of their clinical applications [38, 45, 46, 47].

According to the World Health Organization, superbug-related diseases have killed nearly 700,000 people worldwide in 2019 and are expected to kill 10 million people annually by 2050, making them the leading cause of death globally, posing a significant threat to human health. Consequently, antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), characterized by broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity, low toxicity, and a reduced tendency to induce drug resistance, may evolve into a truly valuable and promising class of novel antimicrobial therapeutic agents in the future.

This review provides a comprehensive and systematic overview and analysis of the research progress regarding the sources, molecular structures, mechanisms of action, as well as design, synthesis, and modification of AMPs, offering valuable insights for related fields. However, current research on AMPs still has certain limitations. For instance, although microalgae-derived AMPs exhibit potential for application in aquaculture, relevant studies are based on single laboratory conditions without considering variables in actual aquaculture environments [48], computer-aided design has improved the efficacy of AMPs, yet it overly relies on in vitro data and overlooks the discrepancy between in vitro and in vivo efficacy. Additionally, the structural stability of AMP molecules is easily affected by pH, and issues such as short half-life, cytotoxicity, and high production costs still restrict their widespread application.

To address these challenges, researchers are constantly exploring new AMPs and modifying existing ones. Currently, the research and development of AMPs is still in the early stages. Further in vitro and in vivo experiments are required to more fully elucidate the mechanism of action of AMPs and fully characterize their structures, thereby enabling their eventual application in human clinical therapy. It is believed that against the backdrop of continuous advancements in science and technology, researchers will achieve greater breakthroughs and accomplishments in AMP research, thereby making more significant contributions to human health and disease treatment.

WRQ design the work, write the manuscript, acquisition and interpretation of data for the work, guide the revision. YXY write part of the content, analysis and interpretation of data, modify and sort out the structure of the review. MYH, ZJL and YXG write part of the content, find information. XZW control academic quality, write and revise. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and are accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

This work is supported by High-performance Computing Platform of Peking University.

Fund of the Natural Science Foundation of Guangxi Province (No. 2024JJB120121, 2024JJB140454), Fund of Natural Science Foundation of China grants (22467006), Fund of Young Elite Scientists Sponsorship Program by GXAST (NO. 2025YESSGX203), and the First-class discipline innovation-driven talent program of Guangxi Medical University), and the Middle/Young aged Teachers’ Research Ability Improvement Project of Guangxi Higher Education (No. 02601222008X), the fund of the first batch of Young Scientists Program in Nanning. This work is supported by High-performance Computing Platform of Peking University.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.