1 Biology Department, College of Sciences, Taif University, 21944 Taif, Saudi Arabia

2 Botany and Microbiology Department, Faculty of Science, Helwan University, 11790 Cairo, Egypt

Abstract

Medicinal plants are abundant in bioactive phytochemicals, which act as shields against harm and disease, and enhance the color, flavor, and aroma of these plants. Therefore, this study aimed to examine and compare the ethnopharmacological potential and phytochemical components of nine Aloe plant species cultivated in the western highlands of Saudi Arabia.

Nine Aloe plant species were collected from different locations (Taif, Al-Baha, Abha, and Jazan). High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was performed on the nine Aloe species, demonstrating the production of six flavonoid compounds with different retention times.

A. parvicoma exhibited the highest concentration of apigenin (45.36 mg/g), A. hijazensis presented the highest for rutin (29.46 mg/g), A. sabaea had the highest of kaempferol (40.12 mg/g), and A. armatissima presented the highest for naringin (60.14 mg/g). Additionally, HPLC was used to separate the six phenolic compounds. A. armatissima had the highest concentrations of ellagic acid, quercetin, and gallic acid (27.99, 39.50, and 40.12 mg/g, respectively), while A. hijazensis had the highest for resorcinol (35.17 mg/g), A. fleurentiniorum had the highest for syringic acid (7.13 mg/g), and A. brunneodentata had the highest for ferulic acid (28.47 mg/g). Four alkaloid compounds were identified, with the highest concentration of coniine (6.58 mg/g) recorded in A. fleurentiniorum, while conhydrine and conmaculatin (5.60 and 4.99 mg/g) were recorded in A. abhaica, and 2-methylpiperidine (3.66 mg/g) was recorded in A. sabaea. The nine Aloe species exhibited significant divergence, as indicated by long Euclidean distances. The considerable concentration of identified compounds denotes the potential use of the Aloe plant species for different pharmacological purposes.

Keywords

- HPLC

- flavonoid compounds

- pharmacological potential

- phenolic compounds

- Aloe

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is the largest country in the Arabian Peninsula, in western Asia. Thus, Saudi Arabia is mostly composed of sand desert, with Rub Al-Khali representing the largest sand desert worldwide [1]. Nonetheless, most of the Aloe species found in Saudi Arabia are located in the diverse ecosystems supported by the southern and western mountain ranges in the country, some of which have peaks that reach nearly 10,000 feet (3000 meters) above sea level. These regions also have more rainfall and more hospitable climates [2]. Among the most well-known succulent plants in the world, Aloe plants can thrive in various habitats and assume different growth forms [3].

Although some Aloe species are harmful, most are thought to provide therapeutic and/or aesthetic benefits [4]. For centuries, Aloe plants have been utilized medicinally [5] to treat ailments [6]. Aloe plants have been used as a traditional cure for several illnesses, including diabetes, heart disease, skin conditions, ulcers, and digestive issues; thus, the use of Aloe plants has transitioned into the pharmaceutical sector [1]. Additionally, Aloe plants are utilized in health and cosmetic items, such as sunscreen, shampoos, lotions, and disinfectants [7]. According to this perspective, bioactive compounds extracted from medicinal plants have been modified to enhance the effectiveness of these compounds in the production of semi-synthetic drugs [6]. Since Aloe plants store water and essential chemical components in their tissues, these plants can tolerate hot and dry weather, making Aloe plants a unique source of phytochemicals [8]. Aloe plants are rich in naturally occurring phytochemicals, including proteins, amino acids, vitamins, hormones, polyphenols, alkaloids, and organic acids [9]. Additionally, Aloe species produced several phenolic compounds, and many more are likely to be discovered in the future [9].

Plants have long been recognized as a great source of bioactive substances with special pharmacological qualities that support human life and wellness [10]. Medicinal plants are rich in bioactive phytochemicals, which protect plants from disease and damage, and contribute to the color, aroma, and flavor of the plant [11]. Compounds dissolved in solution can be isolated, identified, and quantified using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) [5]. This technique is used as a potential tool in biological and chemical research and is also employed in industry to extract and assay complex substance combinations [12]. In addition to developing new drugs or drug formulations, HPLC is utilized in biotechnology, agrochemicals, pharmaceuticals, forensic science, and environmental analysis. Moreover, HPLC is used to quantify compounds in biological samples, purify compounds at the process scale, and improve and characterize biocatalysts [12].

Ethnobotany, a branch of botany and pharmacology, involves examining, documenting, introducing, and publishing information about the traditional use of medicinal plants by local and ethnic groups in traditional, rural, and nomadic areas worldwide [13]. At the end of the 19th century, researchers began extracting, purifying, and identifying bioactive chemicals from plants to examine the pharmacological potential of these compounds as medicinal drugs. The ethnopharmacological qualities of Aloe species, including wound healing, antitumoral, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antimalarial, and anticancer capabilities, have been validated in numerous in vitro and in vivo investigations [14]. These traits were mostly attributed to a range of chemicals present in the phytochemical profile of Aloe extracts rather than to a specific class of compounds [15]. The current study hypothesis is that the estimated Aloe species constitute various chemical compounds with high potential for different medicinal purposes. Consequently, this study aimed to assess the phytochemical constituents of nine Aloe species and separate the chemical compounds using HPLC. The output of this study will enhance the understanding of how these plants are utilized for various pharmacological purposes.

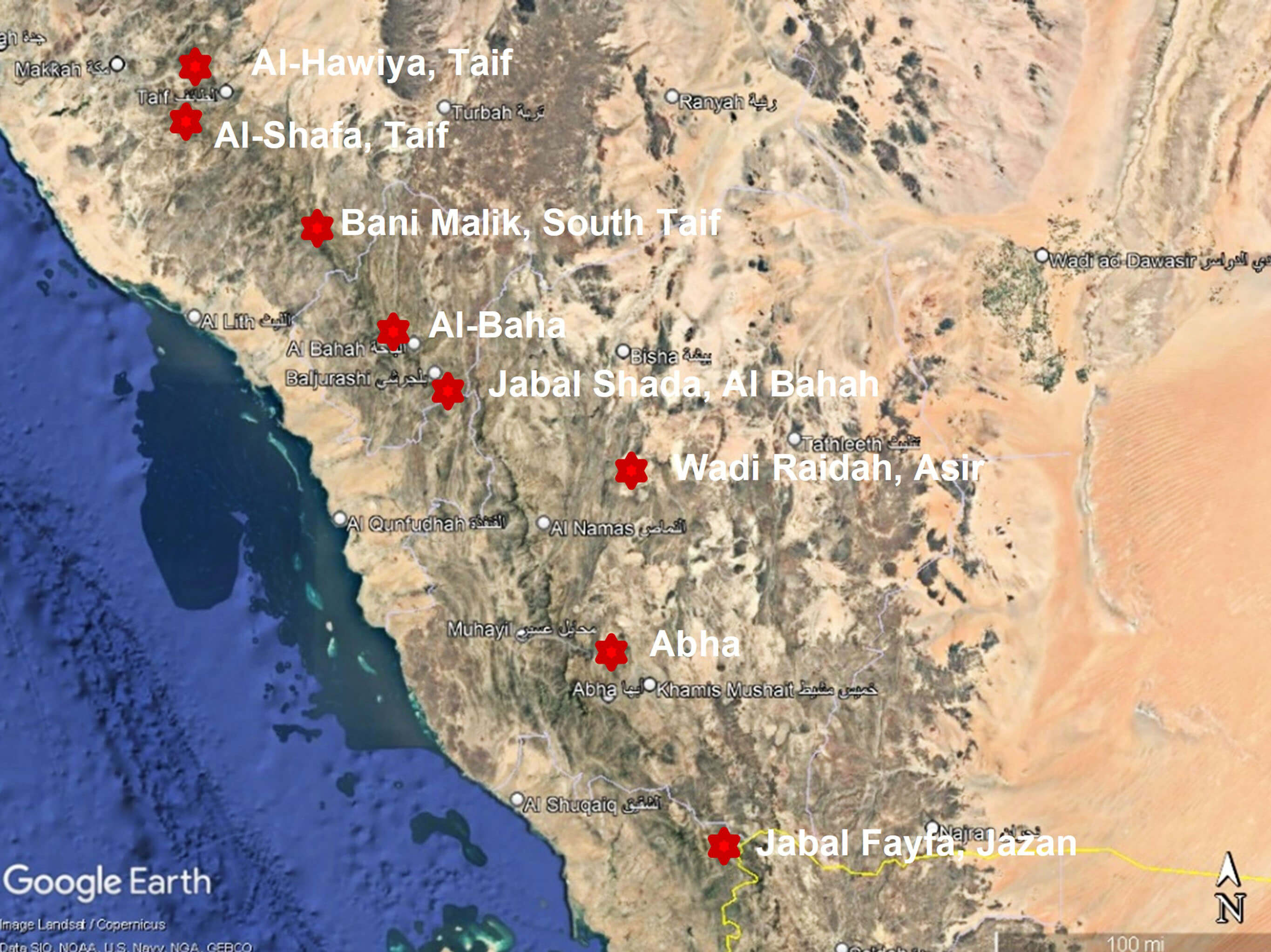

Nine Aloe species were gathered from various locations (Jazan, Abha, Al-Baha, and Taif) in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, and the phytochemical constituents of these plants were assessed (Fig. 1). These species were collected during the spring season of 2022. The included species were as follows: Aloe parvicoma Lavranos & Collen., Aloe x abhaica Lavranos & Collen., Aloe brunneodentata Lavranos & Collen., Aloe armatissima Lavranos & Collen., Aloe vera var. officinalis (Forssk.) Baker, Aloe sabaea Schweinf., Aloe castellorum Wood, Aloe fleurentiniorum Lavranos Newton, and Aloe hijazensis Lavranos & Collen. The collected species were identified and named according to Chaudhary [16] and Collentette [17].

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

A map of the location of the study area with the included sample sites. 18° 56ʹ 34.57ʺ N and 43° 33ʹ 54.21ʺ E. Source: Google Earth, 1 January 2021.

The total flavonoid compounds (TFCs) were determined according to the methods

described by Solich et al. [18] and Tofighi et al. [19]. The TFCherbal material results were calculated, as

quercetin, using the equation: TFCherbal material = (TFCtested solution

The HPLC technique was used to estimate the flavonoid and phenolic compounds of

the assessed Aloe species. Plant flavonoids and phenolic acids were

frequently separated, identified, and quantified using HPLC–mass spectrometry

(MS). The column (ZORBAX Eclipse C18 column) size was 4.6

The matrix of the separated chemical compounds from the different involved species was analyzed using PAST (free software available on the web) (https://past.en.lo4d.com/windows) [22]. Similarity of the quantitative data was calculated using the Nei and Li/Dice similarity index [23], and similarity estimates were performed using the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic averages (UPGMA). The matrices of the mutual coefficients of similarity that were calculated using PAST were clustered (agglomerative clustering), and the resulting clusters are expressed as a dendrogram.

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to evaluate the differences in chemical traits across the various study species after the normality of the data had been checked using SPSS software (Version 22, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) [24]. The occurrence of substantial differences resulted in a post-hoc test being performed according to Duncan’s test.

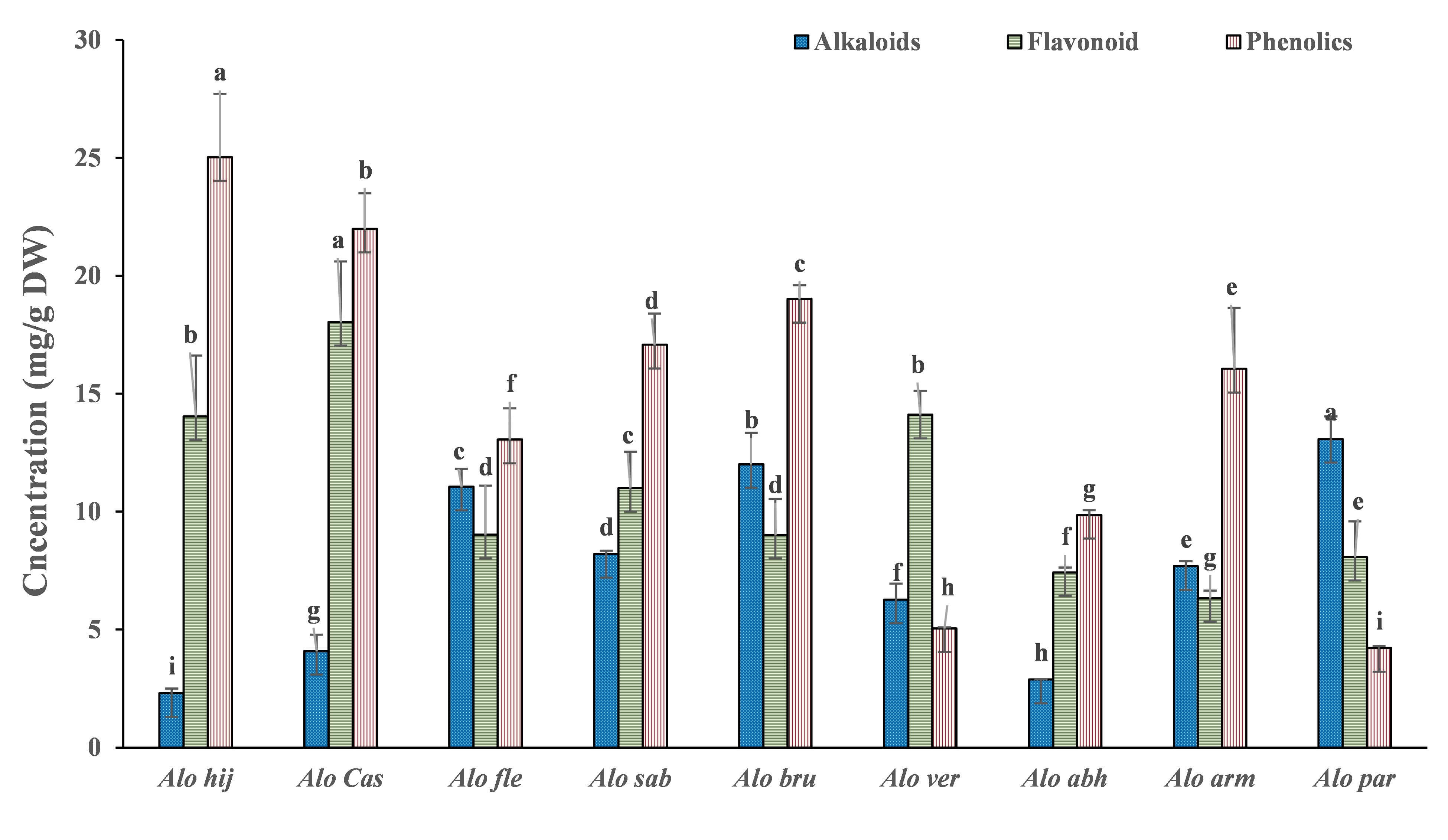

The use of herbal/natural pharmaceuticals as complementary/alternative therapies is becoming increasingly widespread worldwide, with many drugs derived directly from plants and others chemically modified [25]. Studies on the phytochemistry of the genus Aloe have revealed that Aloe species plants are abundant in various classes of compounds, including phenolic compounds, flavonoids, and alkaloids. These compounds have been demonstrated to have antiviral, anti-tumor, and antibacterial properties. Thus, the Aloe genus is being investigated further as a potential alternative medicinal source [26, 27]. Moreover, these compounds can act as a defense mechanism against numerous insects, microorganisms, and herbivores [28]. The results of the current investigation indicated a significant variation in the phenolic compounds, flavonoids, and alkaloids among the shoots of nine Aloe species (Fig. 2). These results aligned with previous findings [29, 30, 31], which recorded varying concentrations of the same chemical constituents in different Aloe species.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Secondary metabolite contents in the shoots of the nine

Aloe species. Data are presented as the mean. Vertical bars represent

the standard deviation. Columns with the same letter are not significant

(p

Secondary metabolites derived from plants are known to comprise numerous structurally varied groups of polyphenols with possible pharmacological actions, such as anti-inflammatory, anticancer, antioxidant, and antipathogenic qualities [26]. A. hijacensis were found to have the highest value of phenolic compounds, but the lowest concentration of alkaloids (25.02 and 2.30 mg/g, respectively). On the contrary, A. parvicoma had the highest content of alkaloids and the lowest concentration of phenolic compounds (13.08 and 4.21 mg/g, respectively). Di Scala et al. [32] recorded higher phenolic contents (0.37 mg/g), but Adesuyi et al. [33] recorded lower phenolic and higher alkaloid contents (2.32 and 24.7 mg/g, respectively) in the tissues of A. vera var. officinalis than those in the investigated Aloe plants. Furthermore, the flavonoid content (32.46 mg/g) recorded by Adesuyi et al. [33] was higher than the highest content (6.33 mg/g) recorded in the tissues of A. castellorum. Phenols are a significant group of substances and can serve as antioxidants or free radical scavengers [33]. However, alkaloids have potential uses in eliminating and reducing the proliferation of human cancer cell lines [34] and as a potential painkiller [35]. Furthermore, flavonoids are antioxidants that have been shown to possess a variety of biological qualities, including cytostatic, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, antiaggregatory, analgesic, and anti-allergic [36].

Generally, a chromatographic technique, such as HPLC, requires reference material that serves as an external standard to determine the amount of an active ingredient or a marker compound present in a crude extract or in preparations made from the material [37]. Quercetin was used to determine flavonoids, while gallic acid was utilized for phenolic compounds. A total of 16 compounds were separated from flavonoids, phenolic acids, and alkaloids (6, 6, and 4, respectively). Similar to this study, Añibarro-Ortega et al. [38] also recorded approximately 17 phenolic compounds in the leaf extracts, and categorized these compounds as anthrones, chromones, flavonoids, and phenolic acids.

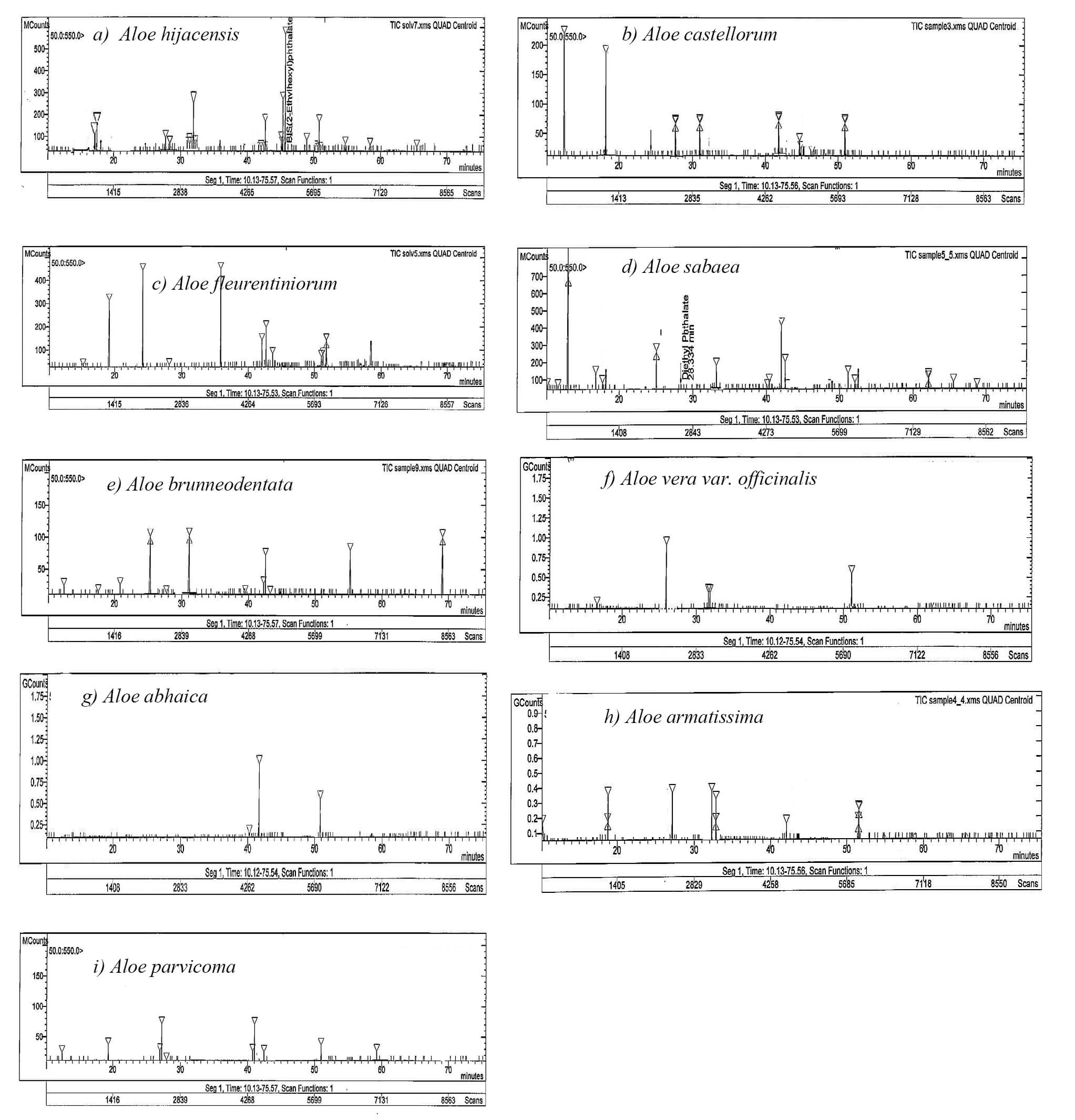

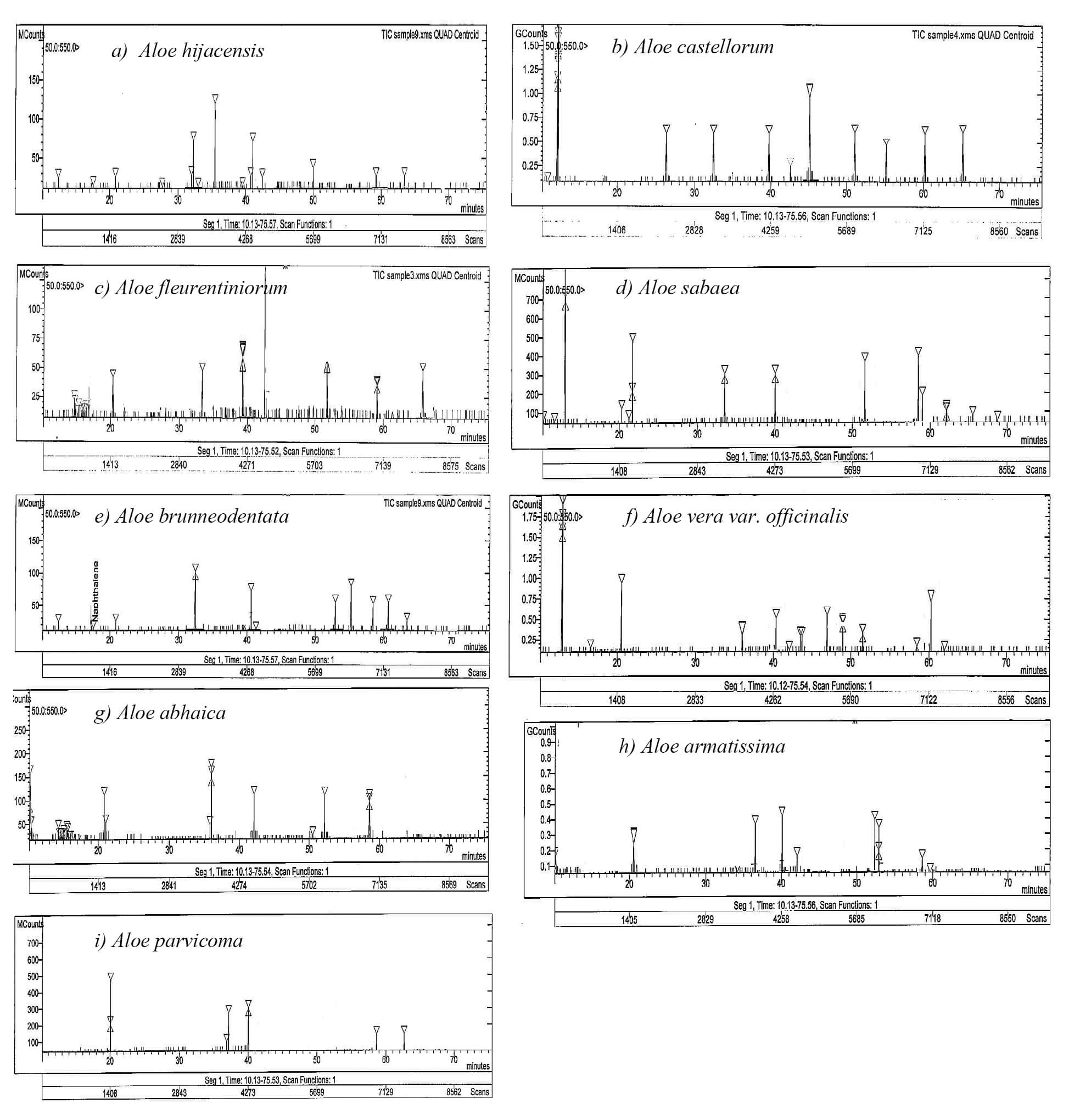

Numerous bacterial strains are inhibited or killed by flavonoids, which also eliminate several harmful protozoans and key viral enzymes, including reverse transcriptase and protease [36]. Flavonoids also act as antioxidants and radical scavengers, exerting a protective effect in several diseases [39]. The HPLC data on the nine Aloe species in this study exhibited six flavonoid compounds with different retention times (RTs) (Table 1 and Fig. 3a–i). These compounds were apigenin, luteolin, naringin, rutin, kaempferol, and hesperetin (RTs = 18, 26, 33, 43, 51, and 59 min, respectively). Kaempferol plays a pivotal role in human nutrition and disease treatment [40]. Furthermore, kaempferol and its related chemicals have antibacterial, antifungal, and antiprotozoal properties in addition to the anticarcinogenic and anti-inflammatory effects [41]. Moreover, apigenin shows efficiency in preventing a wide range of ailments. Apigenin protects against diseases, such as cancer, heart disease, and neurological disorders, by lowering inflammation and oxidative stress, and by promoting cellular health [42]. Luteolin, with potential antioxidant activity, prevents ROS-induced damage and reduces oxidative stress, which is mainly responsible for the pathogenesis of many diseases, and prevents cancer by modulating numerous pathways [43]. Rutin is a polyphenolic flavonoid widely found in garlic and other foods, and improves the health, function, and integrity of the liver and has several biological benefits, including antimicrobial, anticarcinogenic, antithrombotic, cardioprotective, and neuroprotective properties [44].

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

HPLC profile of the flavonoid compounds in the leaf exudates of the nine Aloe species (a–i). The peaks correspond to the compounds presented in Table 1.

| Peak | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Compound | Apigenin | Luteolin | Naringin | Rutin | Kaempferol | Hesperetin |

| RT (min) | 18 | 26 | 33 | 43 | 51 | 59 |

RT, retention time; HPLC, high-performance liquid chromatography.

Moreover, there were marked variations in the concentrations of the separated flavonoid compounds among the nine Aloe species (Table 2). Notably, A. parvicoma had the highest concentration of apigenin (45.36 mg/g). Among all species, it also had the lowest concentration of kaempferol (16.07 mg/g). Meanwhile, A. hijazensis had the highest concentration of rutin (29.46 mg/g), but the lowest apigenin and luteolin (5.36 and 2.66 mg/g, respectively). Comparatively, the highest concentration of kaempferol (40.12 mg/g) and the lowest of rutin (4.69 mg/g) were recorded in A. sabaea, while A. armatissima contributed the highest concentration of naringin (60.14 mg/g), whereas A. brunneodentata had the lowest (14.36 mg/g). Naringin is a common bioactive polyphenol found in citrus fruits, which have been consumed since ancient times and are beneficial to human health. Notably, naringin is an excellent alternative supplemental remedy that can alleviate the situations of cancer patients by suppressing the development of cancer in different body areas [45]. Furthermore, hesperetin (6.99 mg/g) was exclusively recorded in the tissues of A. parvicoma. Hesperetin is abundant in orange and grape juices and is consumed in daily diets. Hesperetin also has vitamin-like properties and can reduce fragility, leakiness, and capillary permeability (vitamin P). Additionally, hesperetin has exhibited strong anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and neuroprotective properties in many neurodegenerative models [46].

| Species | Flavonoids concentration (mg/g) | |||||

| Apigenin | Luteolin | Naringin | Rutin | Kaempferol | Hesperetin | |

| Aloe hijazensis | 5.36d | 2.66f | ND | 29.46a | ND | ND |

| Aloe castellorum | 19.36c | 32.07a | 56.39a | ND | 20.14de | ND |

| Aloe fleurentiniorum | 7.59d | 12.33de | ND | 15.78c | 24.19c | ND |

| Aloe sabaea | ND | 28.61ab | 45.63b | 4.69e | 40.12a | ND |

| Aloe brunneodentata | ND | 20.25c | 14.36d | 8.56d | ND | ND |

| Aloe vera var. officinalis | ND | 28.65ab | 17.6c | ND | 17.69e | ND |

| Aloe abhaica | ND | ND | ND | 17.6c | 22.4cd | ND |

| Aloe armatissima | 36.77b | 9.61e | 60.14a | 22.45b | 35.06b | ND |

| Aloe parvicoma | 45.36a | 14.9d | ND | 27.69ab | 16.07e | 6.99a |

The maximum and minimum values are underlined. ND, not detected. The mean values

with the same letters are not significant (p

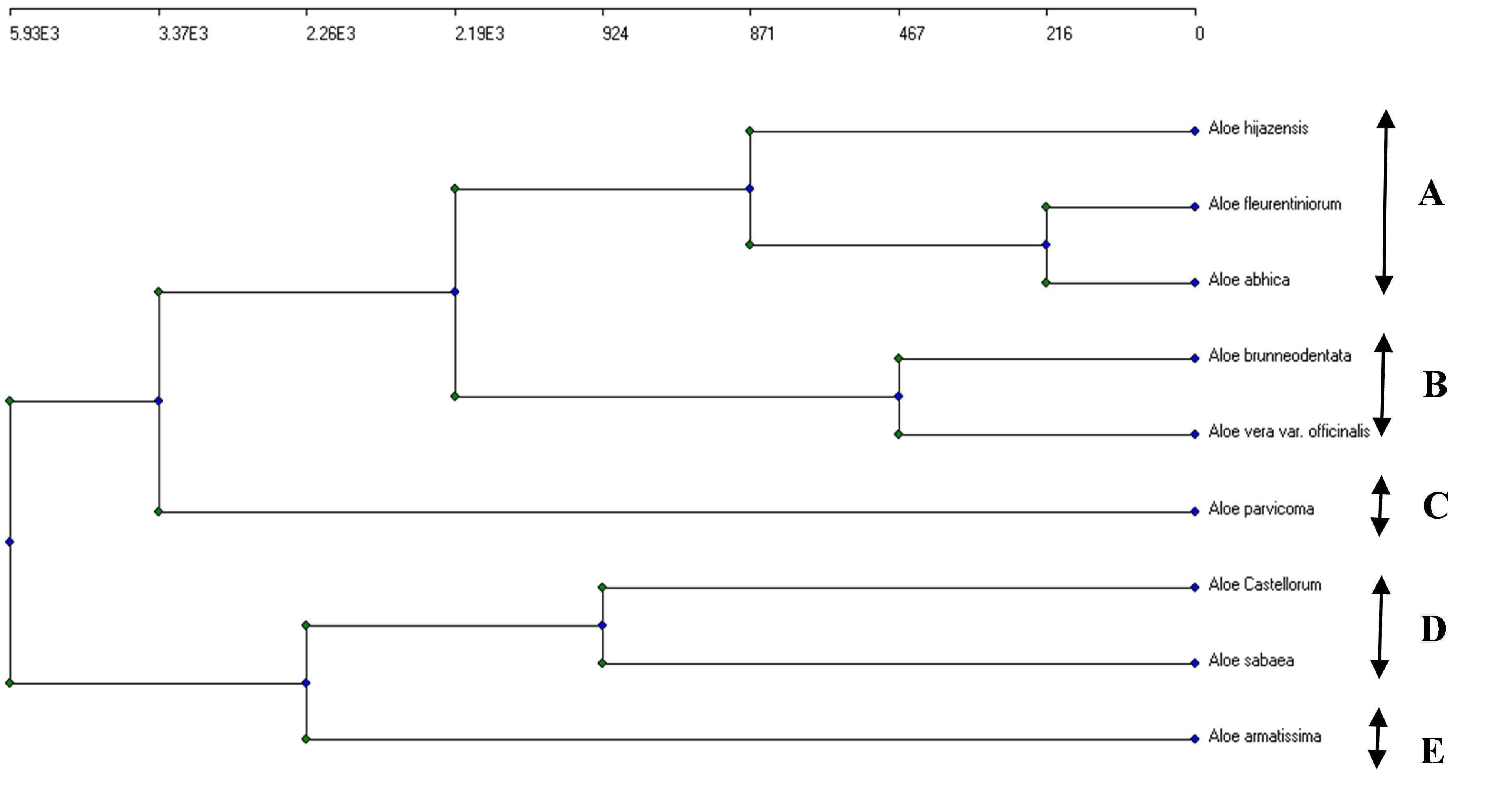

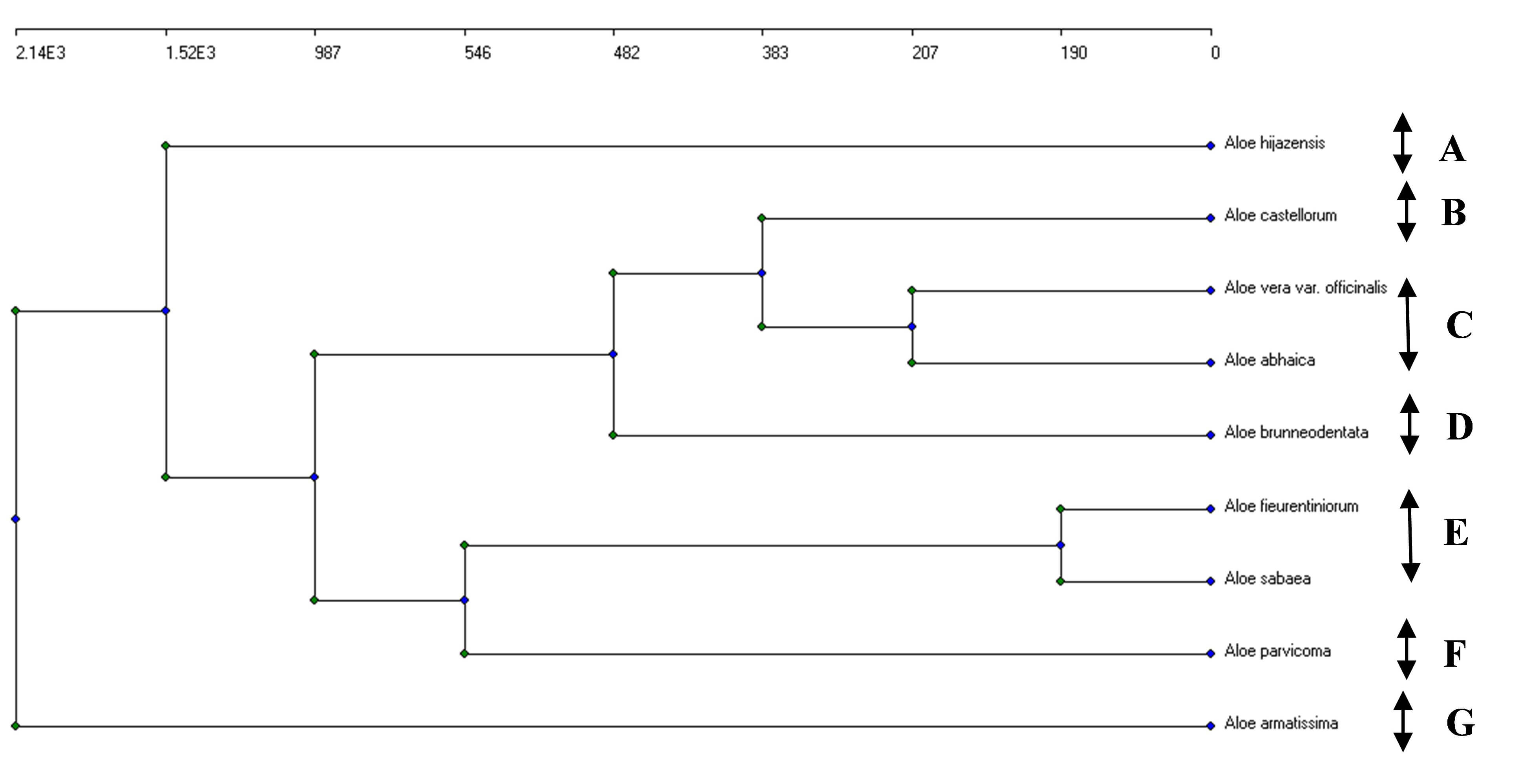

The agglomerative clustering technique was used to group the nine Aloe species into five clusters based on the flavonoid chemicals found in the plant leaves (Fig. 4): (A) A. hijazensis, Aloe fleurentiniorum, and Aloe abhaica; (B) A. brunneodentata and Aloe vera var. officinalis; (C) A. parvicoma; (D) A. sabaea and A. castellorum; (E) A. armatissima.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

The agglomerative clustering dendrogram of the concentrations of the six flavonoid compounds identified in the HPLC analysis of the nine Aloe species. (A) A. hijazensis, Aloe fleurentiniorum, and Aloe abhaica; (B) A. brunneodentata and Aloe vera var. officinalis; (C) A. parvicoma; (D) A. sabaea and A. castellorum; (E) A. armatissima. Arrows represent five segregated clusters.

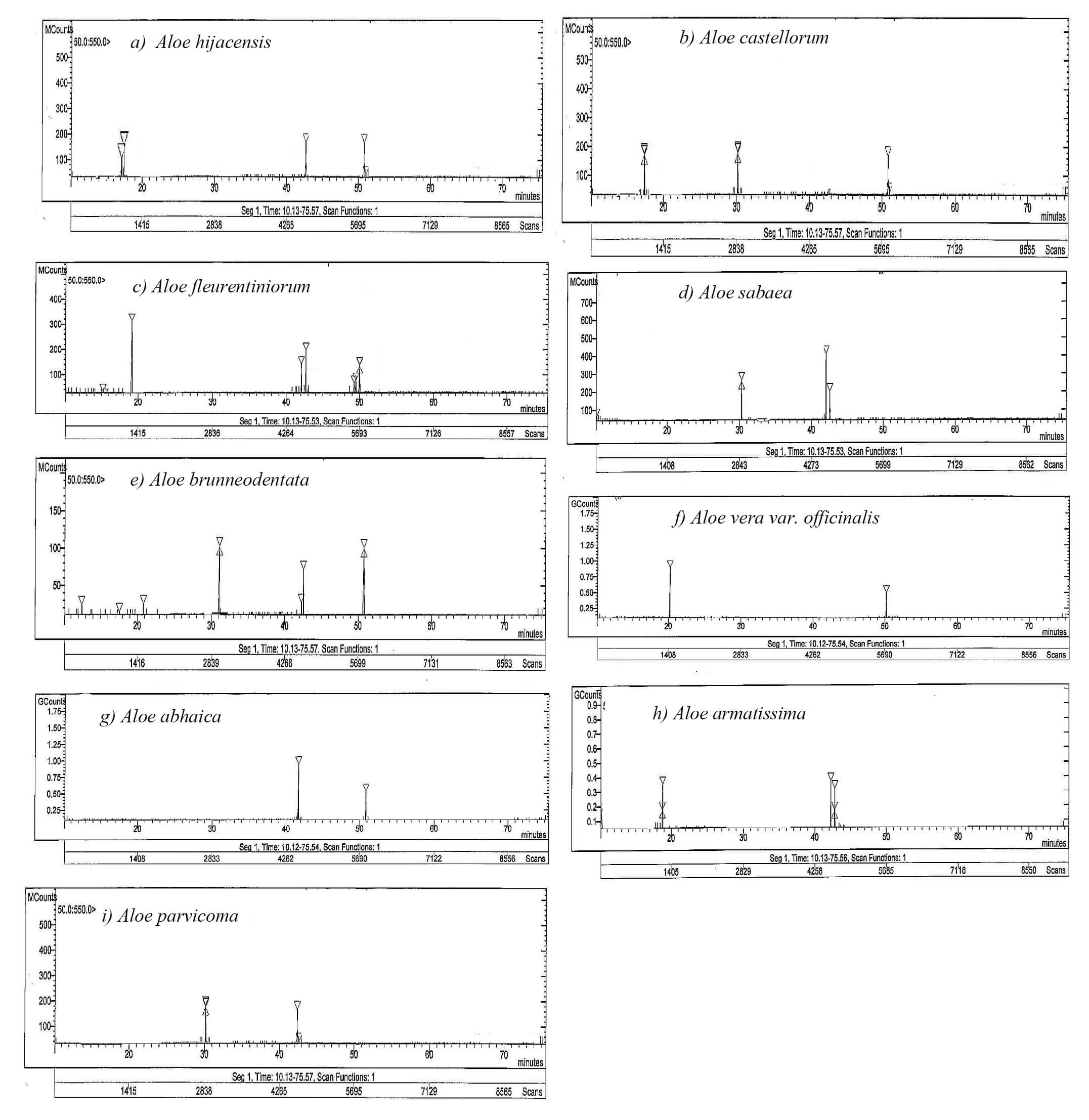

Plant phenolics are considered an essential part of the human diet and offer many health advantages, including strong antioxidant activity [47]. The HPLC data for the nine study Aloe species identified six phenolic compounds with different RTs (Table 3 and Fig. 5a–i). These compounds were identified as ellagic acid, ferulic acid, quercetin, resorcinol, gallic acid, and syringic acid (RT = 20, 36, 40, 54, 59, and 64 min., respectively).

| Peak | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Compound | Ellagic acid | Ferulic acid | Quercetin | Resorcinol | Gallic acid | Syringic acid |

| RT (min) | 20 | 36 | 40 | 54 | 59 | 64 |

RT, retention time.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

HPLC profiles of the phenolic compounds in the leaf exudates from the nine Aloe species (a–i). The peaks correspond to the compounds presented in Table 4.

Marked variations were observed in the concentrations of the separated phenolic substances among the nine Aloe species (Table 4). Plant phenolics are considered an essential part of the human diet and offer many health advantages, including strong antioxidant activity [48]. Thus, phenolics are an important compound that can be used as an anticarcinogenic [49], multiple-function protector against oxidative stress [50], and anti-inflammatory substance for treating chronic ulcerative colitis [51]. In addition, quercetin, a flavonoid present in fruits and vegetables, has a common role in preventing various pathogeneses, as this compound can inhibit inflammation, oxidative stress, and strengthen the natural antioxidant defense systems in the body [52]. Humans have been consuming gallic acid, a phenolic acid found in fruits and vegetables, for generations. Indeed, gallic acid is known to promote antimicrobial, antioxidant, anticancer, anti-inflammatory, and antiviral qualities, among other well-established health advantages [53].

| Species | Phenolic compounds (mg/g) | |||||

| Ellagic acid | Ferulic acid | Quercetin | Resorcinol | Gallic acid | Syringic acid | |

| Aloe hijazensis | ND | 22.44b | 16.54d | 35.17a | 7.21g | ND |

| Aloe castellorum | ND | 15.69c | 1.47h | 19.14b | 10.14fg | 1.23bc |

| Aloe fleurentiniorum | 18.66b | 4.17g | 15.24de | 3.12g | 22.67cd | 7.13a |

| Aloe sabaea | 27.60a | 4.63g | 19.55cd | 4.12f | 28.99bc | ND |

| Aloe brunneodentata | ND | 28.47a | 9.25f | 7.14e | 19.88de | ND |

| Aloe vera var. officinalis | 5.33c | 9.56de | 8.65g | ND | 15.36e | 1.25bc |

| Aloe abhaica | 4.19d | 8.26ef | ND | 10.25cd | 20.16cd | ND |

| Aloe armatissima | 27.99a | 6.78f | 39.50a | 7.66de | 40.12a | ND |

| Aloe parvicoma | 15.36b | 10.22de | 24.19b | ND | 7.45g | 0.99c |

The maximum and minimum values are underlined. ND, not detected. The mean values

with the same letters are not significant according to Duncan’s test. p

The highest concentrations of ellagic acid, quercetin, and gallic acid were noted in A. armatissima (27.99, 39.50, and 40.12 mg/g, respectively), while A. hijazensis had the highest concentration of resorcinol (35.17 mg/g). In addition, A. fleurentiniorum presented the highest concentration of syringic acid (7.13 mg/g), and A. brunneodentata had the highest concentration of ferulic acid (28.47 mg/g). Fruits, vegetables, and drinks, such as coffee and beer, are all rich sources of ferulic acid, a compound that has shown promise as a treatment option for several illnesses, including viral and bacterial infections, inflammation, diabetes, neurological problems, and heart disease [54]. Topical pharmaceutical medicines that treat skin conditions and infections, such as seborrheic dermatitis, acne, psoriasis, eczema, calluses, corns, and warts, contain resorcinol as an antiseptic and disinfectant. Moreover, resorcinol has a keratolytic effect. Although, resorcinol has anti-thyroidal properties, it is not used for any official therapeutic indication [55]. Syringic acid is frequently found in vegetables and fruits and contains antioxidant, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, antiendotoxic, neuro, and hepatoprotective properties [56]. Thus, syringic acid exhibits many therapeutic uses, including in preventing cancer, diabetes, and cerebral ischemia.

Conversely, the lowest concentration of ellagic acid (4.19 mg/g) was recorded in the aboveground tissues of A. abhaica, while the lowest concentrations of ferulic acid and resorcinol (4.17 and 3.12 mg/g) were recorded in A. fleurentiniorum. Moreover, the lowest concentrations of quercetin, gallic acid, and syringic acid (1.47, 7.21, and 0.99 mg/g) were found in A. castellorum, A. hijazensis, and A. parvicoma, respectively.

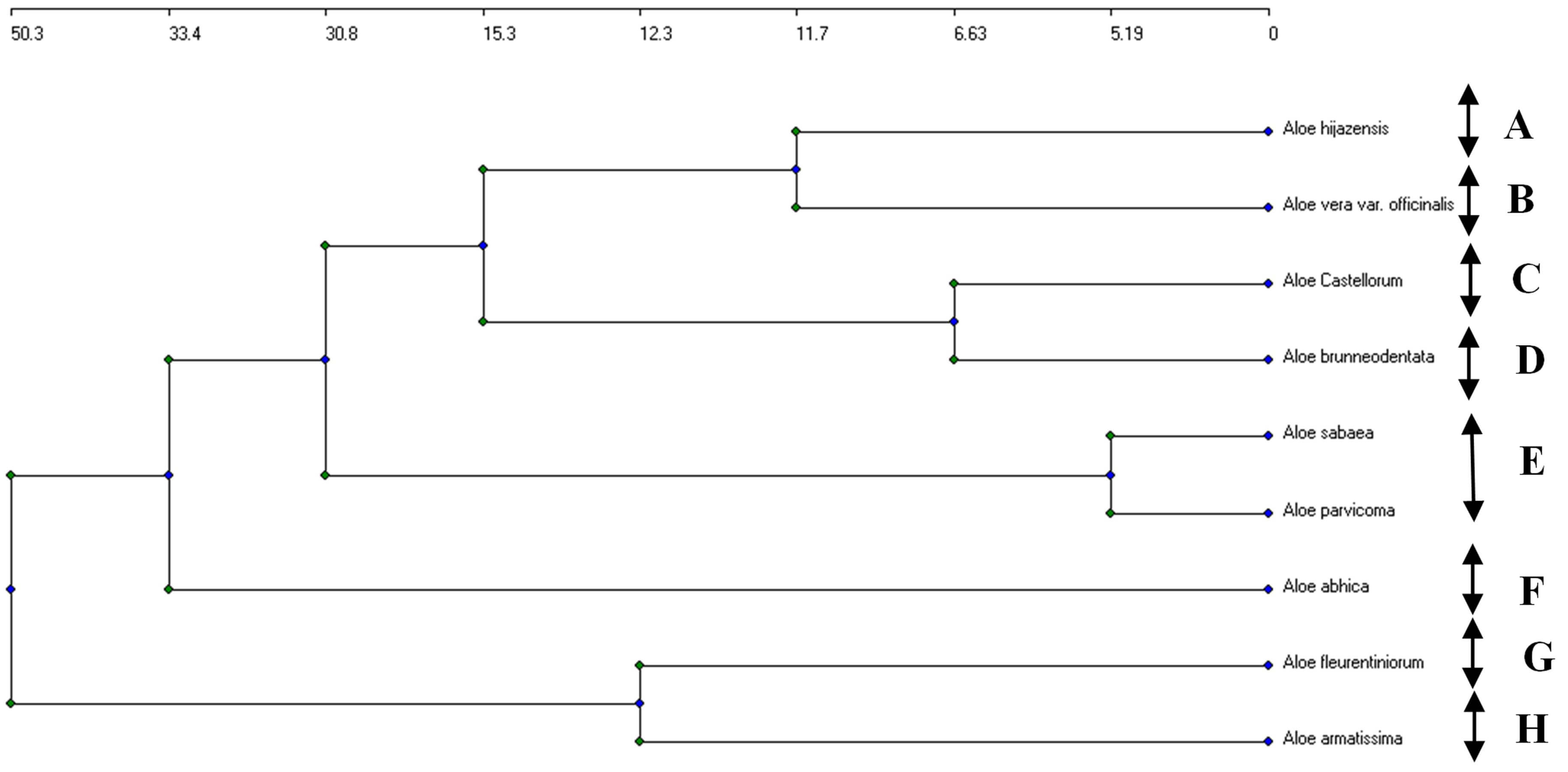

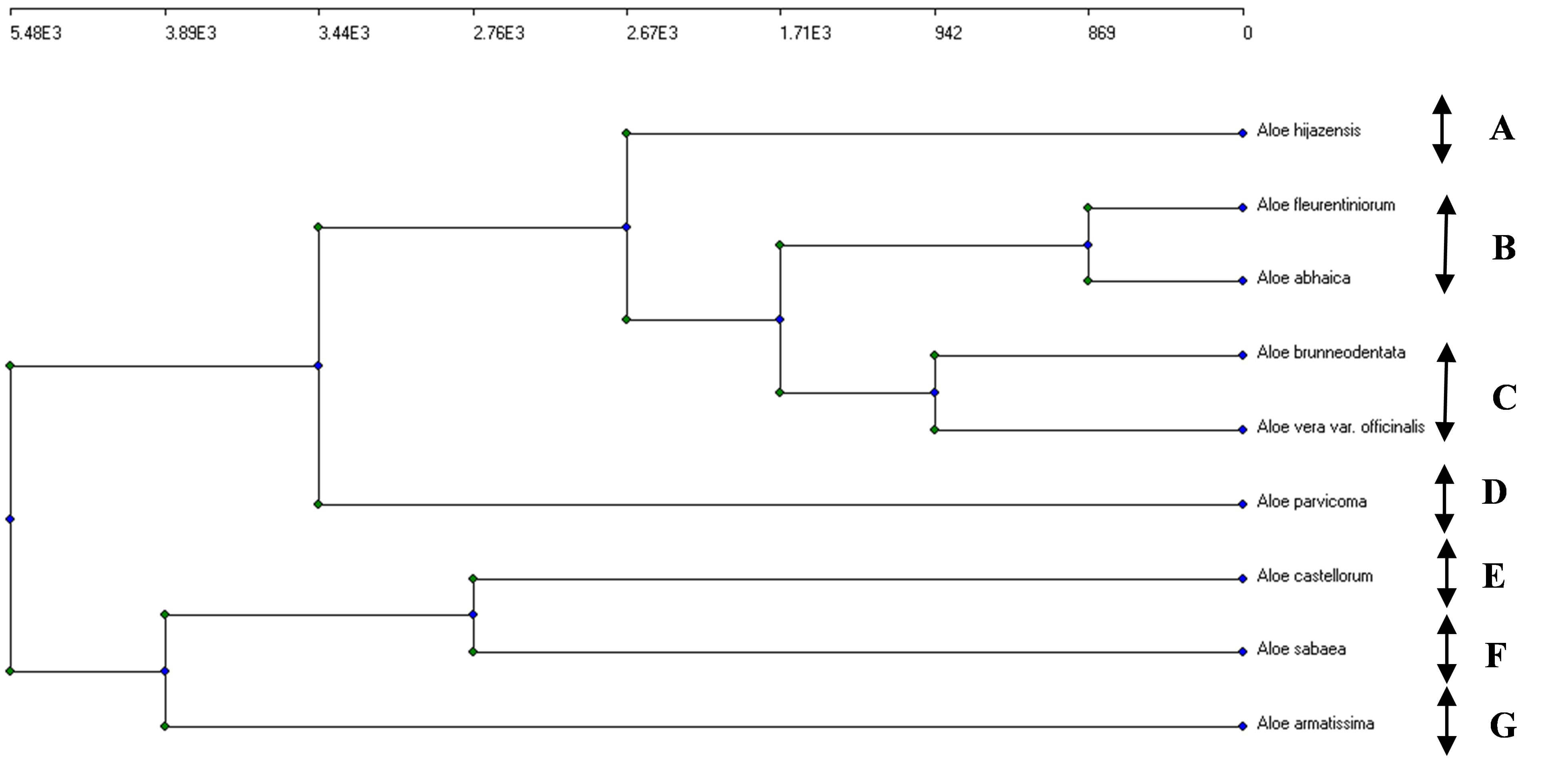

Based on the phenolic compounds recorded in the nine Aloe species, seven clusters were segregated by applying the agglomerative clustering technique (Fig. 6): (A) A. hijazensis; (B) A. castellorum; (C) Aloe vera var. officinalis and A. abhaica; (D) A. brunneodentata; (E) A.fleurentiniorum and A. sabaea; (F) A. parvicoma; (G) comprised A. armatissima.

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

An agglomerative clustering dendrogram of the concentrations of the six phenolic compounds identified in the HPLC analysis of the nine Aloe species. (A) A. hijazensis; (B) A. castellorum; (C) Aloe vera var. officinalis and A. abhaica; (D) A. brunneodentata; (E) A.fleurentiniorum and A. sabaea; (F) A. parvicoma; (G) comprised A. armatissima. Arrows represent five segregated clusters.

The HPLC data on the nine studied Aloe species identified four alkaloid compounds with different RTs (Table 5 and Fig. 7a–i). These compounds are coniine (RT = 18 min), 2-methylpiperidine (RT = 30 min), conhydrine (RT = 44 min), and conmaculatin (RT = 50 min). This result aligns with that published by [57], who reported a few alkaloid compounds in A. vera var. officinalis. Various plant species, including Aloe, are known to contain the alkaloid coniine. However, despite the possibility that coniine is hazardous, this alkaloid is no longer used medicinally due to a limited window for treatment [58]. Additionally, piperidine causes musculoskeletal abnormalities in newborn animals and is acutely hazardous to adult cattle species. These teratogenic effects include several congenital contracture deformities and the introduction of a cleft palate in sheep, goats, pigs, and cattle. Furthermore, tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum), lupine (Lupinus spp.), and poison hemlock (Conium maculatum) are among the poisonous plants that contain teratogenic piperidine alkaloids [59]. Moreover, conhydrine is extracted from the leaves and seeds of the toxic plant C. maculatum L. (Apiaceae), whose extracts were used in Greece for executions [60]. Another volatile alkaloid, conmaculatin, is related to coniine and was recorded in the well-known poisonous weed C. maculatum. Indeed, in mice, conmaculatin exhibited potent central and peripheral antinociceptive action within a limited dose range (10–20 mg/kg) [61].

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

HPLC profiles of the alkaloid compounds in the leaf exudates from the nine Aloe species (a–i). The peaks correspond to the compounds presented in Table 6.

| Peak | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Compound | Coniine | 2-methylpiperidine | Conhydrine | Conmaculatin |

| RT (min) | 18 | 30 | 44 | 50 |

RT, retention time.

The toxicity to foreign organism cells represents the biological characteristic of alkaloids. Meanwhile, the potential applications of alkaloids in the eradication and decrease of human cancer cell lines have been extensively researched [34]. There were marked variations in the concentrations of the separated alkaloid compounds among the nine studied Aloe species (Table 6). A. fleurentiniorum had the highest concentration of coniine (6.58 mg/g), while A. hijazensis presented the lowest (1.25 mg/g). In addition, A. abhaica had the highest concentrations of conhydrine and conmaculatin (5.60 and 4.99 mg/g), while A. brunneodentata and A. fleurentiniorum had the lowest (1.02 and 0.29 mg/g), respectively. Furthermore, the highest content of 2-methylpiperidine (3.66 mg/g) was recorded in the shoots of A. sabaea, while the lowest (1.48 mg/g) was in A. parvicoma. Blitzke et al. [62] had previously found that A. sabaea contains the hazardous piperidine alkaloids, indicating that this plant and other species should be used with caution.

| Species | Alkaloids concentration (mg/g) | |||

| Coniine | Conhydrine | Conmaculatin | 2-methylpiperidine | |

| Aloe hijazensis | 1.25cd | 2.66c | 3.14c | ND |

| Aloe castellorum | 2.60c | ND | 4.01bc | 3.09ab |

| Aloe fleurentiniorum | 6.58a | 1.05d | 0.29e | ND |

| Aloe sabaea | ND | 4.21b | ND | 3.66a |

| Aloe brunneodentata | 0.99d | 1.02d | 2.36d | 2.57b |

| Aloe vera var. officinalis | ND | ND | 4.90ab | ND |

| Aloe abhica | ND | 5.60a | 4.99a | ND |

| Aloe armatissima | 5.20b | 4.26b | ND | ND |

| Aloe parvicoma | ND | 3.55bc | ND | 1.48c |

The maximum and minimum values are underlined. ND, not detected. The mean values

with the same letters are not significant (p

According to [29], the piperidine alkaloid was reported in six Aloe species, whereas coniine was found only in A. viguieri. Notably, not every kind of Aloe species is edible, as some, such as A. vera var. officinalis, may induce negative reactions, contain hazardous chemicals [63], and promote adverse effects [64].

Based on the alkaloid compounds recorded in the nine Aloe species, eight clusters were segregated by applying the agglomerative clustering technique (Fig. 8). The clusters identified were (A) A. hijazensis; (B) Aloe vera var. officinalis; (C) A. castellorum; (D) A. brunneodentata; (E) A. parvicoma and A. sabaea; (F) A. abhaica; (G) A. fleurentiniorum; (H) A. armatissima.

Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

An agglomerative clustering dendrogram of the concentrations of the four alkaloid compounds identified in the HPLC analysis of the nine Aloe species. (A) A. hijazensis; (B) Aloe vera var. officinalis; (C) A. castellorum; (D) A. brunneodentata; (E) A. parvicoma and A. sabaea; (F) A. abhaica; (G) A. fleurentiniorum; (H) A. armatissima. Arrows represent five segregated clusters.

According to the results of the agglomerative clustering applied to the extracted chemical components of the nine Aloe species using the UPGAMA clustering analysis, all of the studied species were distinct from one another with lengthy Euclidean distances (Fig. 9). Moreover, seven similarity clusters were recognized according to the most related species: (A) A. hijacensis; (B) A. fleurentiniorum, A. sabaea, and A. abhaica; (C) A. brunneodentata and A. Vera var. officinalis; (D) A. parvicoma; (E) A. castellorum; (F) A. sabaea; (G) A. armatissima. These differences may be attributed to variations in the environmental conditions [25].

Fig. 9.

Fig. 9.

An agglomerative clustering dendrogram of the concentrations of the 16 compounds identified in the HPLC analysis of the nine studied Aloe species. (A) A. hijacensis; (B) A. fleurentiniorum, A. sabaea, and A. abhaica; (C) A. brunneodentata and A. Vera var. officinalis; (D) A. parvicoma; (E) A. castellorum; (F) A. sabaea; (G) A. armatissima. Arrows represent five segregated clusters.

The present study revealed significant variations in the alkaloids, flavonoids, and phenolic compounds among the shoots of the nine studied Aloe species. A total of 16 compounds were separated from flavonoids (6), phenolic acids (6), and alkaloids (4). The highest concentration of apigenin was found in A. parvicoma, while A. hijazensis had the highest concentration of rutin, A. sabaea had the highest concentration of kaempferol, and A. armatissima contributed the highest concentration of naringin. A. armatissima had the highest concentrations of ellagic acid, quercetin, and gallic acid, while A. hijazensis had the highest concentration of resorcinol, A. fleurentiniorum had the highest concentration of syringic acid, and A. brunneodentata had the highest concentration of ferulic acid. The highest concentration of coniine was recorded in A. fleurentiniorum, while the highest levels of conhydrine and conmaculatin were found in A. abhaica, and 2-methylpiperidine was noted in A. sabaea. The nine Aloe species exhibited significant divergence, as indicated by the extensive Euclidean distances. The identified compounds and the considerable concentrations of each suggest the potential use of these studied Aloe species for various pharmacological purposes. However, caution should be maintained when using A. fleurentiniorum and A. sabaea for medicinal purposes, as these species contain high concentrations of the toxic alkaloid coniine and 2-methylpiperidine, respectively.

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

TG and ME designed the research study. TG, ME and SA performed the research. TG and SA conducted experiments. TG analyzed the data. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The plant materials were gathered from natural habitats in southwestern highlands, Saudi Arabia. The sample collection was done from natural habitats, which requires no permission in Saudi Arabia.

The authors extend their appreciation to Taif University, Saudi Arabia, for supporting this work through project number (TU-DSPP-2024-171).

This research was funded by Taif University, Saudi Arabia, project number (TUDSPP-2024-171).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.