1 Department of Medical Microbiology, Hamidiye Faculty of Medicine, University of Health Sciences, 34668 Istanbul, Turkey

2 Department of Medical Microbiology Laboratory, Darica Farabi Training and Research Hospital, University of Health Sciences, 41700 Kocaeli, Turkey

3 Clinics of Medical Microbiology, Elazig Fethi Sekin City Hospital, 23300 Elazig, Turkey

4 Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Gaziantep University, 27310 Gaziantep, Turkey

5 Department of Medical Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine, Firat University, 23119 Elazig, Turkey

Abstract

Currently, there is a need for alternative antimicrobial and anti-biofilm strategies owing to the combined challenges of multidrug resistance and biofilm formation by Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Thus, this study aimed to investigate the antibacterial and antibiofilm effects of extracts from Thymus serpyllum, Mentha piperita, Rosmarinus officinalis, Tilia cordata, Salvia officinalis, and Thymbra spicata against S. maltophilia, as well as the interactions of carnosic acid, luteolin, and carnosol compounds in these extracts with potential target molecules.

Plant extracts were obtained using a Soxhlet device. Antimicrobial activity against 16 clinical S. maltophilia isolates was evaluated using the disk diffusion method, and the antibiofilm effect was assessed using the microtiter plate method. Carnosic acid, luteolin, and carnosol compounds in the extracts were selected as ligands, and a binding analysis was performed with proteins.

The T. serpyllum extract showed the highest inhibition zone (20.5 ± 2.8 mm; p < 0.005), with dose-dependent antimicrobial activity (1024 μg/mL > 512 μg/mL; p < 0.05). Among the assessed 15 biofilm-producing strains, T. serpyllum inhibited 10, S. officinalis inhibited six, and R. officinalis inhibited five strains. Molecular docking indicated strong binding energies (carnosic acid: –8.51 kcal/mol, luteolin: –7.62 kcal/mol, carnosol: –9.23 kcal/mol) and multiple interactions with the MlaC protein.

These findings suggest that extracts from T. serpyllum, S. officinalis, and R. officinalis may target the Mla pathway and exhibit promising antimicrobial and antibiofilm effects against multidrug-resistant S. maltophilia, likely through the associated active compounds. The molecular docking analyses further supported the potential of these extracts to disrupt membrane integrity by interfering with the Mla system, thereby enhancing bacterial susceptibility to antimicrobial agents. However, additional studies are required to validate these mechanisms and investigate their broader biological implications.

Keywords

- Stenotrophomonas maltophilia

- Thymus serpyllum

- luteolin

- biofilms/drug effects

- molecular docking simulation

S. maltophilia is an emerging nosocomial pathogen with intrinsic antibiotic resistance that primarily affects immunocompromised patients. S. maltophilia usually causes respiratory tract infections with a mortality rate of 20–60% [1]. These bacteria cause respiratory and urinary tract infections by colonizing the surfaces of medical devices and treatment equipment such as urinary catheters, endoscopes, and ventilators [2]. S. maltophilia has many structural components that contribute to its virulence and pathogenicity. Pili/flagella/fimbrial/adhesins enable colonization on living and non-living surfaces; outer membrane lipopolysaccharide causes antibiotic resistance and biofilm formation as well as cell death; diffusible signaling factor causes motility, extracellular enzyme production, lipopolysaccharide synthesis, microcolony formation, and tolerance to antibiotics and heavy metal ions [3, 4]. S. maltophilia has the ability to form biofilms on abiotic surfaces and host (biotic) tissues. This is an important virulence factor for bacteria that plays an important role in nosocomial and multi-bacterial infections, significantly reducing the therapeutic efficacy of important antibiotics, including aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones, and tetracyclines [5].

Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) is the first-choice therapeutic option for treating infections due to its in vitro efficacy and favorable clinical outcomes. Meanwhile, alternative antibiotics such as levofloxacin, tigecycline, ceftazidime, colistin, and ticarcillin-clavulanic acid are also used in cases of resistance to TMP-SMX [6]. Due to the recent increase in antimicrobial resistance in S. maltophilia and because of the biofilm component that contributes to this resistance, there is a need to develop new antimicrobial and antibiofilm agents against S. maltophilia.

Studies have shown that T. serpyllum (wild thyme) plant extracts are effective against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, including Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, and Bacillus subtilis [7, 8]. M. piperita (peppermint), R. officinalis (rosemary), T. cordata (T. linden), S. officinalis (sage), and T. spicata (spiked thyme) plants have also been reported to promote antimicrobial effects [9, 10, 11, 12]. Although some studies have examined the antimicrobial effects of these plant species, no comprehensive research has evaluated the activity of these extracts against multidrug-resistant S. maltophilia, except for T. serpyllum. Unlike previous studies, this study compares six plant extracts and further integrates a molecular docking analysis to explore potential mechanisms of action, thereby offering a more mechanistic and comparative insight into the antimicrobial and antibiofilm potential of these extracts.

In silico molecular docking is used to describe the reactions of molecules and predict the potential associated macroscopic properties. Data obtained from experiments can provide novel information; however, these data do not reveal the mechanism of action in the biological system. Therefore, these mechanisms should be further studied in computer modeling analyses using the structures of biological systems [13].

This study aimed to investigate the antimicrobial and antibiofilm activities of T. serpyllum, M. piperita, R. officinalis, T. cordata, S. officinalis, and T. spicata extracts against S. maltophilia strains and to investigate the possible interactions of the compounds in the most active extracts with the targets in terms of antibacterial activity through the molecular docking method.

T. serpyllum, M. piperita, R. officinalis, T.cordata, S. officinalis, and T. spicata plants were purchased in dried form from an herbalist in Gaziantep in 2023. The purchased material was washed with distilled water and left to dry in a sunless environment for one week. The plant material was then ground into powder, and methanol extracts (50 grams of plant material in 250 mL of methanol) were obtained using a Soxhlet extraction apparatus (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The methanol extracts were concentrated using a rotary evaporator (Heidolph, Schwabach, Germany) at 40 °C and then allowed to dry completely at ambient temperature in a light-protected environment. The dried extracts were stored in a cool, dark place until further use.

The bacterial strains used in this study consisted of eight TMP-SMX-resistant

and eight TMP-SMX-susceptible S. maltophilia strains, which were

obtained as part of the routine microbiological diagnostic workflow at the

hospital. The samples sent to the microbiology laboratory were inoculated on 5%

sheep blood agar, MacConkey agar, and chocolate agar media. The medium plates

were incubated at 35

Plant extracts were dissolved in 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and

concentrations of 1024 µg/mL and 512 µg/mL were

prepared. A total of 20 µL of the prepared solution was pipetted and

impregnated onto sterile 6 cm diameter disks. As a control, 20 µL of

10% DMSO alone was impregnated onto a sterile disk. The prepared disks were left

to dry at room temperature for 24 hours. Inoculum with a density of 0.5 McFarland

(BioMerieux, Marcyl’Étoile, France) was prepared (1

Biofilm production by bacterial isolates was investigated using the method

described by Christensen et al. [14]. With this method, the absorbance

of the crystal violet dye formed in the wells of the microplates was measured in

the spectrometer (Multiskan Go/Thermo Scientific, ABD) at 570 nm. At the end of

the measurement, the mean optical density (OD) of the control group was recorded

as the OD cut-off (ODc) value, and the mean OD of the isolates (ODisolate) was

calculated. Results were evaluated according to the criteria described by

Stepanović et al. [15]: ODisolate

The method used by Pompilio et al. [16] was modified and applied. Fresh

inoculum adjusted to 0.5 McFarland turbidity (1

This study analyzed the compounds carnosol, carnosic acid, and luteolin, which had been previously identified in the literature via high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) as bioactive components in R. officinalis, T. serpyllum, and S. officinalis [17, 18, 19]. Carnosic acid, luteolin, and carnosol compounds were evaluated within the scope of Lipinski’s Rule of Five, which is traditionally used for small-molecule therapeutics. The three-dimensional (3D) structures of these molecules were downloaded in SDF format from the PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

Subsequently, the structure of each molecule was converted into the PDB format using the BIOVIA Discovery Studio Visualizer program (Dassault Systèmes, VélizyVillacoublay, France). The E. coli phospholipid-binding protein MlaC (PDB ID: 5UWA) was selected as the receptor molecule and was downloaded in PDB format from the Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org) database.

Molecular docking analyses were performed using AutoDock 4.0 (The Scripps

Research Institute, La Jolla, CA, USA) [20] to predict the possible binding sites

of carnosic acid and carnosol, which are abundant in R. officinalis and

S. officinalis, and luteolin ligands, which are abundant in T.

serpyllum, on the crystal structure of the MlaC receptor. The MlaC crystal

structure, with a resolution of 1.50 Å, was selected as the target (receptor)

molecule. AutoDock Tools (ADT) software was used to prepare the parameters of the

receptor and ligand molecules before initiating the docking analysis. Polar

hydrogen atoms in the receptor and ligand molecules were retained while nonpolar

hydrogens were incorporated. Gasteiger charges were calculated using ADT as

previously described by Ricci and Netz [21] and Nasab et al. [22].

During the molecular docking experiment, all rotatable bonds in the ligands were

allowed to rotate. The prepared receptor and ligand structures were then saved in

the PDBQT format. A grid box size of 60

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows,

Version 27 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Since the data did not exhibit a normal

distribution (as verified by the Shapiro–Wilk test), non-parametric tests were

employed. The Kruskal–Wallis H-test was applied to compare inhibition zone

diameters and biofilm inhibition rates among different plant extract groups. When

the Kruskal–Wallis test indicated statistically significant differences

(p

The inhibition zone diameters for the S. maltophilia strain formed

using the plant extracts are presented in Table 1. The zone diameter for

T. serpyllum was found to be the highest (p

| Zone diameter (mm) | |||||||||||||

| T. serpyllum | M. piperita | R. officinalis | T. cordata | S. officinalis | T. spicata | ||||||||

| Strain number | TMP-SMX susceptibility | 1024 µg/mL | 512 µg/mL | 1024 µg/mL | 512 µg/mL | 1024 µg/mL | 512 µg/mL | 1024 µg/mL | 512 µg/mL | 1024 µg/mL | 512 µg/mL | 1024 µg/mL | 512 µg/mL |

| 1 | S | 20 | 12 | 20 | 16 | 15 | 10 | 17 | 12 | 19 | 12 | 12 | 0 |

| 2 | S | 19 | 15 | 17 | 13 | 20 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 0 | 13 | 12 |

| 3 | S | 19 | 11 | 18 | 15 | 20 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 7 | 13 | 12 |

| 4 | S | 20 | 12 | 19 | 13 | 20 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 10 | 0 |

| 5 | S | 18 | 10 | 14 | 7 | 13 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 0 | 10 | 0 |

| 6 | S | 28 | 16 | 24 | 16 | 21 | 16 | 14 | 6 | 21 | 0 | 15 | 10 |

| 7 | S | 19 | 11 | 16 | 7 | 16 | 10 | 14 | 10 | 16 | 11 | 18 | 13 |

| 8 | S | 26 | 19 | 20 | 16 | 21 | 19 | 21 | 19 | 19 | 14 | 14 | 11 |

| 9 | R | 18 | 11 | 15 | 11 | 15 | 9 | 15 | 13 | 16 | 0 | 14 | 0 |

| 10 | R | 19 | 9 | 14 | 6 | 17 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 10 | 6 |

| 11 | R | 20 | 16 | 17 | 17 | 18 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 13 | 8 |

| 12 | R | 21 | 15 | 20 | 17 | 17 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 14 | 11 | 7 |

| 13 | R | 24 | 16 | 20 | 15 | 17 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 14 | 17 | 12 |

| 14 | R | 20 | 15 | 17 | 15 | 16 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 18 | 0 | 12 | 8 |

| 15 | R | 19 | 12 | 16 | 15 | 16 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 0 | 12 | 6 |

| 16 | R | 18 | 9 | 14 | 8 | 14 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 0 | 8 | 0 |

R, resistance; S, susceptible; TMP-SMX, Trimethoprim/Sulfamethoxazole. The susceptibility of S. maltophilia strains to TMP/SMX was determined using the VITEK®2 COMPACT device. The inhibition rates of plant extracts against these strains at concentrations of 1024 µg/mL and 512 µg/mL were determined using the disk diffusion test. Zone diameters were measured with a ruler. The length was recorded in millimeters.

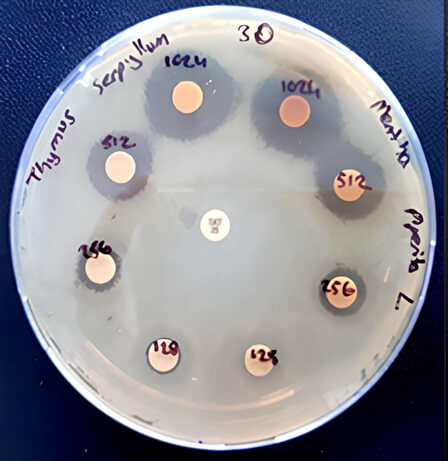

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Inhibition zones for T. serpyllum and M. piperita extracts against S. maltophilia strain (number 12) at concentrations of 1024 µg/mL, 512 µg/mL, 256 µg/mL, and 128 µg/mL.

In total, 15 of the S. maltophilia strains isolated from 16 different clinical samples produced a biofilm, whereas one strain did not. When the biofilm production capacities of the strains were examined, 11 were observed as strong, 2 were medium, and 2 were weak (Table 2).

| Strain no. | R/S | Biofilm degree | TMP-SMX | T. serpyllum | S. officinalis | R. officinalis |

| 1 | S | - | N | N | N | N |

| 2 | S | +++ | 90 | 56 | 68 | 77 |

| 3 | S | + | 100 | 68 | 55 | 0 |

| 4 | S | ++ | 99 | 32 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | S | +++ | 90 | 7 | 23 | 27 |

| 6 | S | +++ | 90 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | S | +++ | 99 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | S | +++ | 90 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | R | +++ | 99 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | R | +++ | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 11 | R | + | 100 | 82 | 56 | 0 |

| 12 | R | ++ | 90 | 57 | 0 | 83 |

| 13 | R | +++ | 90 | 73 | 54 | 57 |

| 14 | R | +++ | 94 | 30 | 0 | 0 |

| 15 | R | +++ | 91 | 76 | 58 | 56 |

| 16 | R | +++ | 99 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

R, resistance; S, susceptible; N, none; +++, strong biofilm; ++, medium biofilm; +, weak biofilm; -, no biofilm.

After biofilm formation was confirmed in the microplates, planktonic bacteria were washed with TMP-SMX (4 mg/mL), and extracts of rosemary, thyme, and sage (8 mg/mL) were added to the remaining biofilms. CAMHB was used as a positive control, and 100% DMSO was used as a negative control. Biofilm inhibition rates were calculated using OD600 measurements and are presented as percentages compared to the controls.

Among the 15 biofilm-producing strains, while TMP-SMX inhibited bacterial growth

in all strains to varying degrees, rosemary inhibited bacterial growth in five

strains, sage in six strains, and thyme in 10 strains. Among the extracts, the

highest activity against the strain was observed for the T. serpyllum

(thyme) extract (p

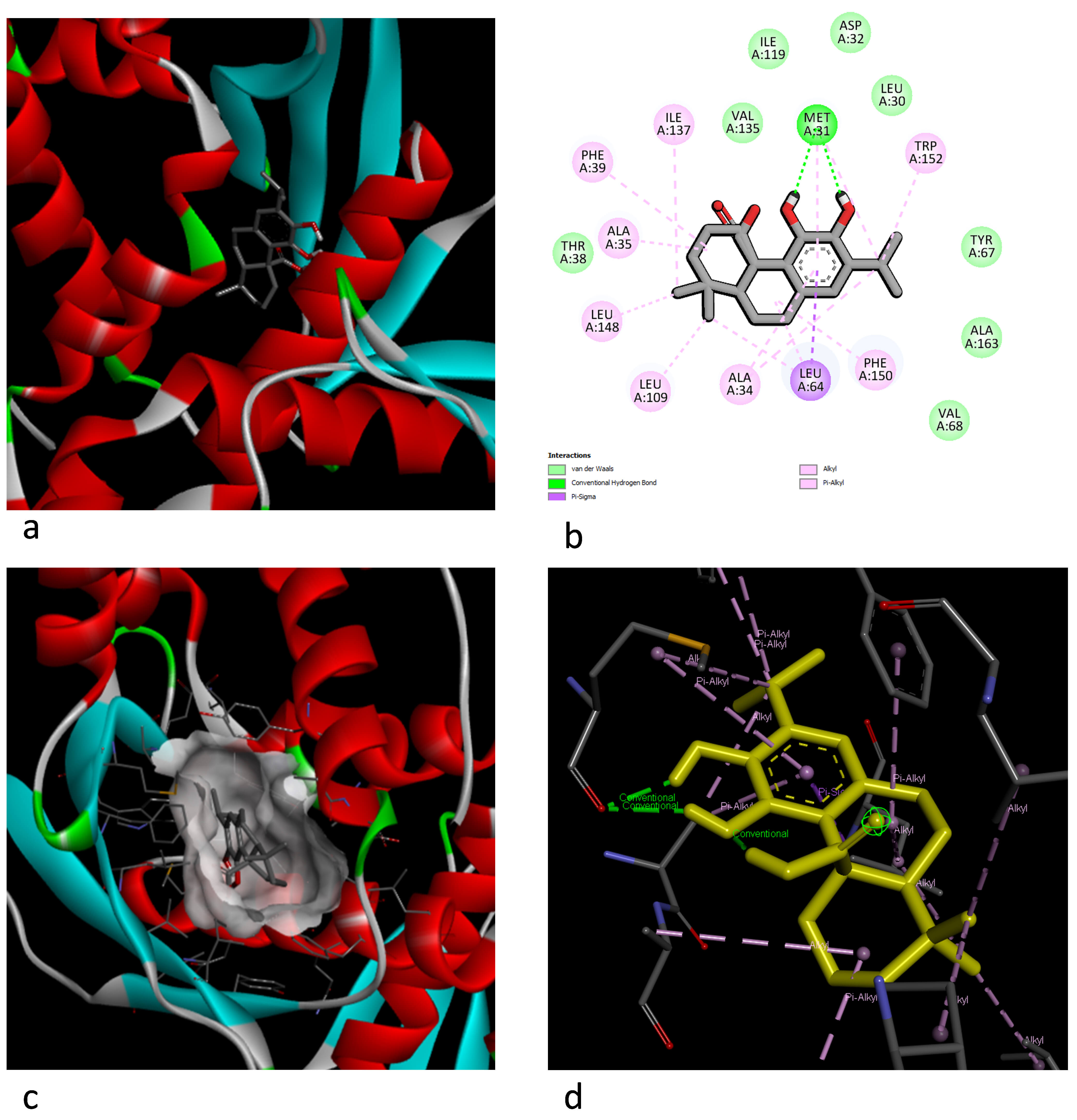

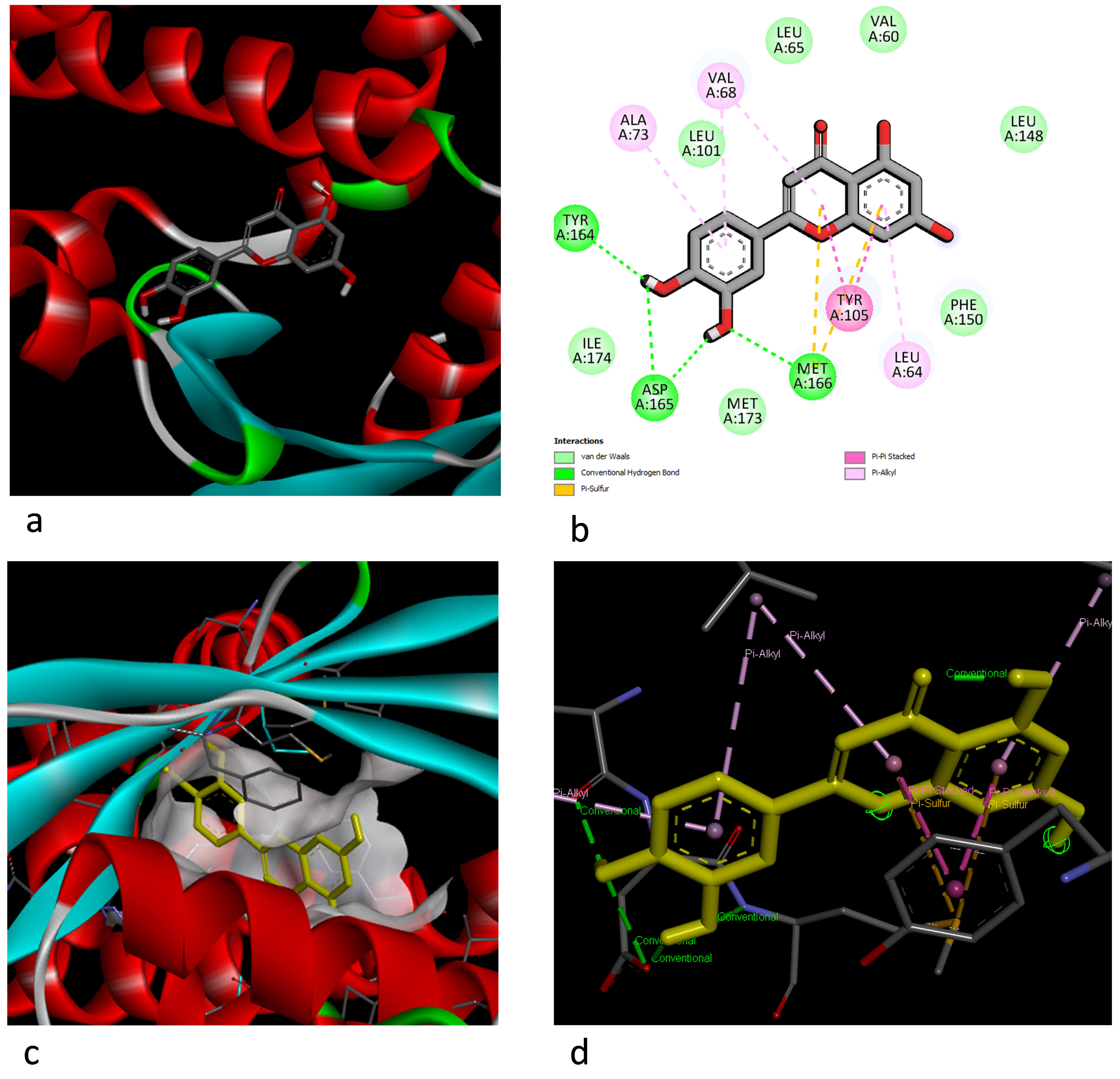

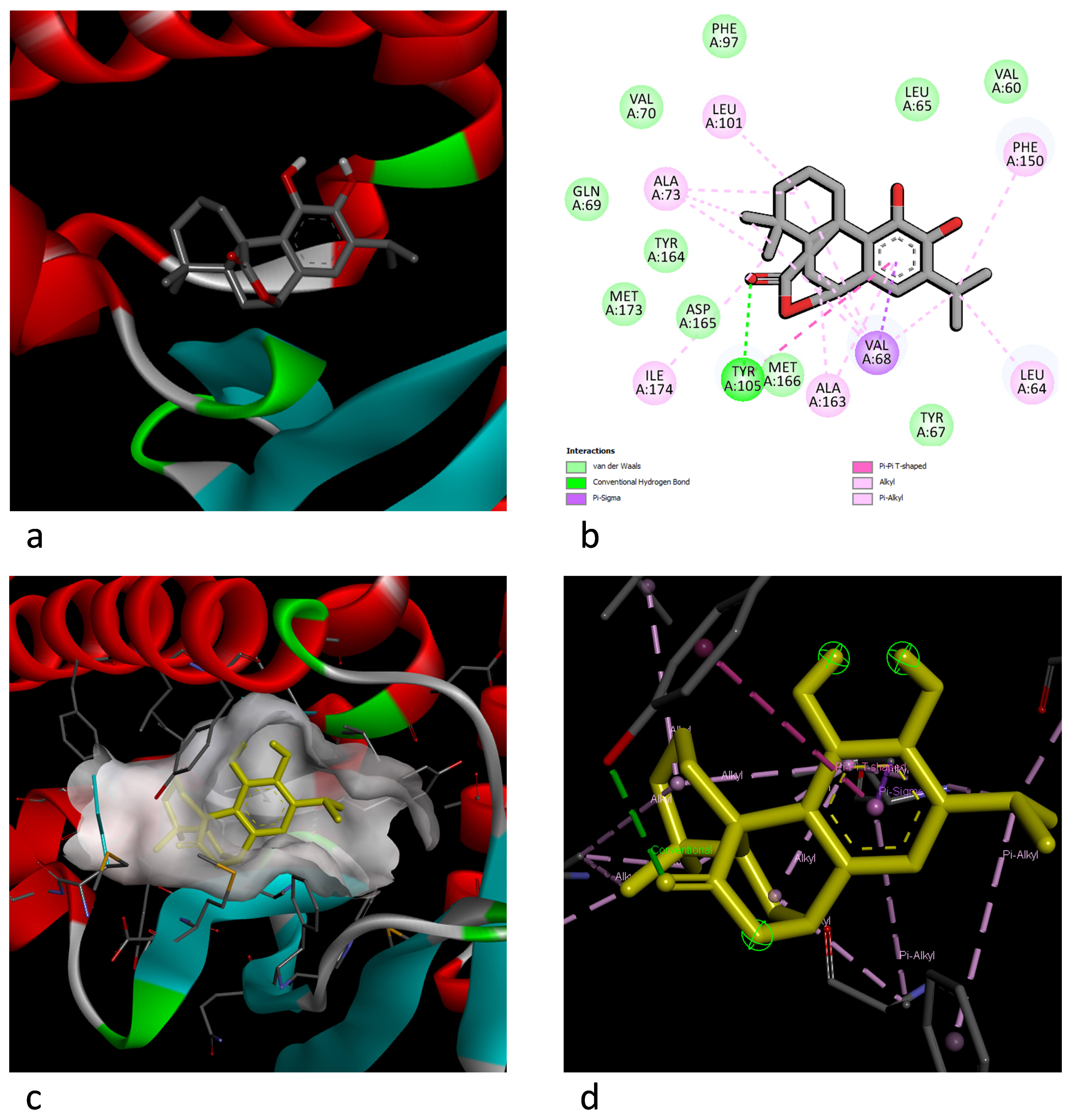

The amino acid interactions of the ligands with the target protein MlaC are

shown in Figs. 2,3,4. The lowest Gibbs free binding energies (

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Representation of the docking interaction between carnosic acid and MlaC. (a) Best 3D docking pose. (b) The two-dimensional (2D) aa interaction and chemical bond types. (c) The 3D electric field interaction. (d) Ligand interaction pose.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Illustration of the docking interaction between luteolin and MlaC. (a) Best 3D docking pose. (b) The 2D aa interaction and chemical bond types. (c) The 3D electric field interaction. (d) Ligand interaction pose.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Illustration of the docking interaction between carnosol and MlaC. (a) Best 3D docking pose. (b) The 2D aa interaction and chemical bond types. (c) The 3D electric field interaction. (d) Ligand interaction pose.

S. maltophilia is naturally resistant to many antibiotics, including beta-lactams, aminoglycosides, macrolides, tetracyclines, and carbapenems. This poses serious challenges in the treatment of S. maltophilia infections. Currently, the most effective antibiotic is TMP-SMX; however, resistance to TMP-SMX has increased over recent years [24, 25]. Indeed, a systematic review reported that the resistance rate of S. maltophilia to TMP/SMX was 9.2% worldwide between 2000 and 2022 [26]. These data highlight that reliance on TMP-SMX alone may not be sustainable in the long term, and alternative therapeutic strategies are urgently required.

Moreover, in a study by Pompilio et al. [16], which analyzed 109 S. maltophilia isolates from various clinical samples, the authors noted that the majority of the assessed strains (91.7%) were capable of producing biofilms. Additionally, Bilgin et al. [27] determined that a significant portion (87.2%) of the 78 evaluated S. maltophilia isolates from pulmonary and extrapulmonary samples formed biofilms, and Sun et al. [28] reported that 42 (82%) of 51 hospital-acquired S. maltophilia isolates also formed biofilms.

In the present study, 15 of the 16 assessed clinical S. maltophilia

strains (93%) were found to produce biofilms; furthermore, 11 were determined to

have a strong biofilm production capacity, two a moderate capacity, and two a

weak capacity. The results of our study are consistent with those of other

studies, indicating that S. maltophilia strains exhibit a high

capacity for biofilm production. This strong biofilm-forming ability may partly

explain the persistence and multidrug resistance of S. maltophilia in

clinical environments. Meanwhile, no significant difference was found in our

study between the biofilm production capacities of TMP-SMX-resistant and

susceptible strains (p

To our knowledge, no previous studies have investigated the antibacterial

activity of T. serpyllum, R. officinalis, T. cordata,

and S. officinalis extracts against S. maltophilia. However,

our study demonstrates significant antibacterial activity by the T.

serpyllum methanolic extract. Balkan et al. [29] reported that

essential oils from T. serpyllum have shown inhibition zones

A study on methanol and water extracts from T. spicata showed the

formation of inhibition zones of 23 mm and 16 mm, respectively [31]. In this

study, the inhibition zone of the methanol extract from T. spicata was

found to be 12.63

While the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for the ethanol extract from

M. piperita against S. maltophilia is reported in the

literature as

Although, to our knowledge, no previous antimicrobial studies have been

conducted on T. cordata extracts against S. maltophilia, Ali

et al. [11] tested alkaloid, flavonoid, and glycoside extracts on

S. aureus and E. coli. Notably, while no antimicrobial activity

was observed against E. coli in this study [11], the flavonoid extract

showed activity against S. aureus, producing an 18 mm inhibition zone at

a high concentration of 3 mg/mL. This low level of antimicrobial activity is

consistent with the weak antibacterial effect of T. cordata extracts

observed in our study. Furthermore, the significantly reduced impact of

T. cordata extracts on resistant S. maltophilia strains in our

findings (p

Zhang et al. [33] reported that a disc impregnated with 50% R. officinalis essential oil produced a 13.83 mm inhibition zone against S. maltophilia. In our study, the methanol extract (primarily containing polar compounds) demonstrated a larger inhibition zone (17.25 mm). This observation suggests that the bioactive compounds in the polar fraction of R. officinalis could exhibit stronger antimicrobial effects compared to the essential oil. Additionally, partial evaporation of volatile components from the essential oil during testing might have contributed to this difference. These findings could be interpreted to indicate that the polar extract of R. officinalis may potentially offer therapeutic advantages over the essential oil against resistant S. maltophilia strains. Moreover, this finding implies that polar extracts may be advantageous for developing stable formulations compared to volatile essential oils.

In our study, we observed an inhibition zone of 16.81 mm against S.

maltophilia using a total extract of S. officinalis. Interestingly,

this finding is comparable to results reported by Kačániová

et al. [34], who demonstrated a 16.47

Pietruczuk-Padzik et al. [35] reported that among all the tested plant extracts against Staphylococcus species, T. serpyllum and Taraxacum officinale leaf extracts exhibited the most promising antibacterial activity, both against planktonic cultures and biofilm forms. Kačániová et al. [34] found that T. serpyllum essential oils inhibited Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm at a concentration of 0.236 mg/mL, while Čabarkapa et al. [36] reported that this essential oil prevented biofilm formation by Salmonella enteritidis strains. In our study, the T. serpyllum extract demonstrated biofilm inhibition activity in 66.7% of the S. maltophilia strains. These findings support the potential of T. serpyllum to suppress biofilm formation in various bacterial species.

Wijesundara and Rupasinghe [37] reported that the essential oils from S. officinalis significantly inhibited biofilm formation of Streptococcus pyogenes strains at 0.25 mg/mL and were able to eradicate existing biofilms at 0.5 mg/mL. Ünlü et al. [38] also reported that this essential oil inhibited biofilm formation in 41.2% of the tested methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) isolates, with varying degrees of inhibition. In the present study, S. officinalis extract exhibited biofilm inhibition activity in 40% of S. maltophilia strains. These findings indicate that S. officinalis can exert biofilm-suppressing effects on various bacterial species.

Ben Abdallah et al. [39] reported the potent antibiofilm activity of R. officinalis (rosemary) essential oils against MRSA, and Jardak et al. [40] demonstrated the effectiveness of the same essential oils against Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilms. Galovičová et al. [41] also reported that these essential oils inhibited S. maltophilia biofilms. In our study, the methanolic extract of R. officinalis showed lower inhibition (33.3%) against S. maltophilia biofilms. This difference in efficacy may be due to differences in extract type and concentration ratio.

Su et al. [42] reported that the minimum biofilm eradication concentration was above 1 mg/mL for all the studied strains. Similarly, Río-Chacón et al. [43] reported that the minimum biofilm eradication concentration value was above 5 mg/mL for the majority of strains. In our study, a TMP-SMX concentration of 4 mg/mL inhibited the formation of mature biofilm structures in all tested strains. Our results, when evaluated in conjunction with the literature, indicate that high doses of TMP-SMX are necessary for inhibiting S. maltophilia biofilms. However, systemic application of this concentration in humans is not possible. Therefore, the obtained data may simply guide the evaluation of alternative treatment strategies, such as topical applications, implant coatings, or the development of new drug delivery systems.

According to our results, the T. serpyllum extract exhibited the

highest antibacterial and antibiofilm activity with statistical significance

(p

In the analyses conducted by Sonmezdag et al. [44] using the gas chromatography–mass spectrometry–olfactometry (GC–MS–olfactometry) and liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization–tandem mass spectrometry (LC–ESI–MS/MS) techniques, 24 volatile compounds were identified in the aroma profile of T. serpyllum, most of which were classified as terpenes. Phenolic compound analysis revealed 18 different phenolics, with luteolin-7-O-glucoside, luteolin, and rosmarinic acid being the most prominent.

Recent metabolomic studies using ultra-high-performance liquid

chromatography–electrospray ionization–quadrupole-time-of-flight mass

spectrometry (UHPLC–ESI–QTOF-MS) have elucidated the distinct yet overlapping

phytochemical profiles of R. officinalis and S. officinalis [45, 46]. These analyses revealed that rosemary is particularly rich in bioactive

diterpenes, with Soxhlet extraction yielding high concentrations of carnosol

(22,000.67

The Mla ABC transport system, which is known to transport phospholipids across the periplasm in Gram-negative bacteria and plays a role in maintaining outer membrane homeostasis, is also found in S. maltophilia. The Mla system plays a role in basic resistance to antimicrobial and antibiofilm agents. The periplasmic substrate-binding protein MlaC is an important component in this system and has been shown to bind to phospholipids, thereby contributing to basic resistance to various antimicrobial agents [50]. In this study, the E. coli phospholipid-binding protein MlaC (PDB ID: 5UWA) was selected as a model receptor in the docking analysis. When we examined the molecular docking results, strong hydrogen bond interactions were observed with MET31 in the amino acid residues of the carnossic acid molecule and the MlaC receptor-binding motif (RBM), while van der Waals interactions were observed with the THR38, VAL135, ILE119, ASP32, LEU30, TYR67, ALA163, and VAL68 residues. In addition, a Pi-Sigma bond interaction was observed with LEU64, while alkyl and Pi–alkyl bond interactions were determined with ALA34, LEU109, LEU148, ALA35, PHE39, ILE137, TRP152, and PHE150. When the luteolin and MlaC docking interaction was examined, hydrogen bonds were observed for the TYR164, ASP165, and MET166 residues, and van der Waals interactions were observed for the ILE174, LEU101, LEU65, VAL60, PHE150, and MET173 residues. The MET166 residue also formed a second interaction: a Pi–sulfur bond. While the TYR105 residue showed a Pi–Pi interaction, the LEU65, ALA73, and VAL68 residues exhibited Pi–alkyl interactions.

In the carnosol–MlaC docking interaction, van der Waals interactions were observed for the MET166, ASP165, MET173, TYR164, GLN69, VAL70, PHE97, LEU65, VAL60, and TYR67 residues, and both hydrogen bonding and Pi–Pi–T interactions were observed for TYR105. Additionally, carnosol exhibited Pi–Sigma interactions for the VAL68 and ALA163 residues. Moreover, the ILE174, ALA73, LEU101, PHE150, and LEU64 residues showed alkyl and Pi–alkyl interactions.

The binding energy threshold is accepted as –6.0 kcal/mol. In our study, the results were accepted as significant because all ligand–receptor Gibbs free binding energies were more negative than –6.0 kcal/mol. When designing molecular docking analyses, the antimicrobial activity was predicted to occur via the Mla pathway. The Mla system consists of 6 proteins, MlaA, MlaB, MlaC, MlaD, MlaE, and MlaF, which transport phospholipids from the outer leaflet of the outer membrane to the inner membrane. MlaA is a lipoprotein located in the outer membrane and transfers phospholipids to MlaC, which is a periplasmic protein [51]. MlaC transfers phospholipids to the Mla–FEDB complex in the inner membrane, and Mla–FEDB then inserts phospholipids into the inner membrane [52]. In this study, the MlaC protein within the Mla system was specifically targeted owing to the central and unique role MlaC plays in the lipid transport function in the Mla system. MlaC is the sole periplasmic, soluble protein that transports phospholipids between MlaA in the outer membrane and the Mla–FEDB complex in the inner membrane. Since most other Mla components are membrane proteins, these components are structurally less accessible; in contrast, MlaC offers a directly inhibitory target [53]. Previous studies have demonstrated that the functional loss of mlaC increases bacterial susceptibility to several classes of antibiotics. Bernier et al. [54] showed that mlaC mutants in Burkholderia cepacia complex strains exhibited increased sensitivity to tetracyclines, chloramphenicol, macrolides, fluoroquinolones, and rifampin compared to wild-type strains. This highlights the functional relevance of MlaC as a potential target in antimicrobial resistance mechanisms. Moreover, inactivating the Mla system eliminates the lipid asymmetry of the outer membrane and increases the sensitivity to various antimicrobial agents in many Gram-negative bacteria [53]. When these results are evaluated in conjunction with in vitro antimicrobial activity studies, carnosic acid, carnosol, and luteolin compounds, which are abundantly found in T. serpyllum, R. officinalis, and S. officinalis extracts, are highlighted in terms of antimicrobial activity and may be potential active antibacterial substances.

This study has certain limitations, including the relatively small number of clinical isolates and the exclusive use of in vitro assays, which may not fully reflect the complexity of in vivo conditions. Moreover, variations in extract composition related to plant origin, harvest time, and extraction method could affect reproducibility. Despite these limitations, these findings provide preliminary evidence supporting the antibacterial and antibiofilm activity of selected plant extracts against S. maltophilia. Importantly, this work addresses a gap in the literature by, to our knowledge, being the first to evaluate the activity of T. serpyllum, R. officinalis, T. cordata, and S. officinalis extracts against S. maltophilia and by proposing the Mla system as a possible molecular target. Nonetheless, further investigations focusing on the standardization of extract preparation, the exploration of potential synergistic effects with existing antibiotics, and the experimental validation of molecular docking predictions would strengthen the clinical relevance of these results.

This study demonstrated that extracts of T. serpyllum, S.

officinalis, and R. officinalis possess measurable antimicrobial and

antibiofilm activities against multidrug-resistant S. maltophilia. The

most active extract was from T. serpyllum, producing an inhibition zone

of 20.5

The datasets used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

YA and ZAT designed the research study. YA, HA, and IHK performed the research and conducted experiments. YA, HA, and IHK analyzed the data. BNE and FFS contributed to literature review, methodology development, and writing – review & editing. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Approval for this study was obtained from the Istanbul Health Sciences University Umraniye Training and Research Hospital Clinical Research Ethics Committee (approval number: 228473746, date: 02 November 2023). The study was carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written consent was obtained from the patients or their families/legal guardians.

The authors would like to thank Master Student Uğur Vural and PhD Student Zeynep Çelik for their guidance in antimicrobial activity studies.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.