1 Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, College of Medicine, Kosin University, 49267 Busan, Republic of Korea

2 Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology, College of Medicine, Dong-A University, 49201 Busan, Republic of Korea

3 Division of Neuroanatomy, Department of Neuroscience, Yamaguchi University Graduate School of Medicine, 755-8505 Ube, Japan

4 Department of Biomedical Science, Graduate School, Kyung Hee University, 02447 Seoul, Republic of Korea

5 Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology, College of Medicine, Kyung Hee University, 02447 Seoul, Republic of Korea

6 Department of Precision Medicine, College of Medicine, Kyung Hee University, 02447 Seoul, Republic of Korea

Abstract

Flavopiridol (Flavo), a synthetic flavonoid derived from Dysoxylum binectariferum, broadly inhibits cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) that regulate transcription in proliferative cells. In the peripheral nervous system, Schwann cells exhibit transcriptional changes during peripheral neurodegenerative processes (PNPs), involving c-Jun and Krox20 as key regulators. Additionally, hydrogen sulfide (H2S) promotes neuroprotection by activating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, which induces cyclin D1 via β-catenin nuclear translocation.

To assess the therapeutic potential of Flavo in the PNPs, we conducted experiments targeting Schwann cell responses both in vivo and ex vivo. Moreover, we examined changes in transcriptional regulation, focusing on c-Jun and Krox20, and analyzed the effect of Flavo on the H2S/β-catenin/CDK signaling pathway using Western blot and morphological evaluation of demyelination, axonal degeneration, and Schwann cell proliferation.

Flavo modulated Schwann cell transcription by shifting the c-Jun/Krox20 balance and significantly suppressed abnormal Schwann cell proliferation. The in vivo analysis revealed that Flavo dose-dependently reduced demyelination and axonal degeneration. Mechanistically, Flavo inhibited the H2S/β-catenin/CDK axis, reducing β-catenin nuclear translocation.

Our findings suggest that Flavo provides multifaceted protection in peripheral nerves by correcting transcriptional dysregulation and attenuating key pathological features of Schwann cell dysfunction. Administering Flavo, in relation to the H2S/β-catenin/CDK pathway, may represent a promising therapeutic strategy for peripheral neurodegenerative diseases through multitarget transcriptional modulation.

Keywords

- Schwann cells

- flavopiridol

- peripheral neurodegenerative process

- hydrogen sulfide

- β-catenin

Schwann cells are unique glia in the peripheral nervous system (PNS) that function to maintain the myelin sheath around peripheral axons, which causes saltatory conduction. Peripheral neurodegenerative process (PNP) occurs in the PNS under abnormal conditions, such as mechanical or toxic injury, and Schwann cells play roles both degenerating and repairing injured Schwann cells functionally and morphologically [1]. After completing PNP Schwann cells promote regeneration of axons to the destination and remyelinate axons to recover saltatory conduction. Therefore, Schwann cells have an all-round capability to solve whatever occurs in the PNS. However, aberrant PNP, such as diabetes mellitus, induces irreversible PNP and ultimately causes peripheral neurodegenerative diseases, such as peripheral diabetic neuropathy [2]. No pathogenetically targeted treatment has been identified.

Schwann cells, the principal glial components of the PNS, are essential for preserving the structural and functional integrity of myelinated axons by forming and maintaining the myelin sheath that enables saltatory conduction. Under pathophysiological conditions, such as mechanical trauma or chemical insult, Schwann cells are not only implicated in the degeneration of damaged nerves but also initiate regenerative responses by undergoing phenotypic and transcriptional reprogramming. This dual role underscores their intrinsic capacity to mediate both degenerative and reparative processes following peripheral nerve injury [1]. Once Wallerian degeneration is complete, Schwann cells facilitate axonal regrowth and remyelination, thereby restoring conduction velocity and functional connectivity. Owing to this multifaceted responsiveness, Schwann cells serve as central effectors in the orchestration of peripheral nerve homeostasis. However, chronic or systemic disorders, including diabetes mellitus, can disrupt this balance and give rise to maladaptive or incomplete regenerative programs, resulting in irreversible PNP. Such persistent degeneration is a hallmark of peripheral neurodegenerative pathologies like diabetic peripheral neuropathy, for which no disease-modifying therapies currently exist [2].

During PNP, Schwann cells undergo dynamic transcriptional reprogramming that determines their phenotypic fate. In myelinating Schwann cells, positive regulators such as Krox20, as an alias of early growth response 2 (Egr2), SRY-box transcription factor 10 (Sox10), and Oct6, as an alias of POU class 3 homeobox 1 (POU3F1), activate the expression of myelin-related genes [e.g., myelin protein zero (Mpz), peripheral myelin protein 22 (Pmp22)], reinforcing a stable myelinating state [3]. Conversely, injury-induced demyelination triggers negative transcriptional regulators, particularly c-Jun, which actively represses Krox20-driven programs and promotes a repair phenotype. c-Jun not only suppresses myelin gene expression but also induces pro-regenerative factors such as glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) and sonic hedgehog (Shh) [4]. While transient c-Jun activation is essential for effective debris clearance and axon guidance, its sustained expression impedes remyelination. Additionally, during demyelination, aberrant activation of canonical Wnt signaling in Schwann cells leads to stabilization and nuclear translocation of

Flavopiridol (Flavo), a synthetic derivative of the natural compound rohitukine derived from Dysoxylum binectariferum, functions as a potent cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor known to suppress cyclin D1 expression [6, 7]. In our investigation, Flavo demonstrated the most pronounced attenuation of PNP phenotypes in vivo, notably reducing both axonal degradation and demyelination. Moreover, Flavo modulated transcriptional activity and effectively inhibited

Primary antibodies used in this study included cystathionine

Five-week-old healthy male C57BL/6 mice were procured from Samtako Bio Korea (Osan, Korea) and maintained under standard laboratory conditions (23

For the in vivo peripheral nerve injury model, sciatic nerve axotomy was conducted under sterile conditions, as previously described [8]. Anesthesia was induced via intraperitoneal administration of pentobarbital sodium (35 mg/kg body weight, #P3761, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Pentobarbital sodium was dissolved in sterile saline to prepare a 50 mg/mL stock solution, filtered through a 0.22 µm syringe filter, and stored at 4 °C protected from light. The dosage was adjusted according to body weight to achieve surgical anesthesia. Following transection, the distal segment of each sciatic nerve was enclosed in a 10-mm blind-ended polyvinyl chloride (PVC) tube filled with gel foam pre-soaked in Flavo and maintained in situ for 1 to 4 days. Based on this gross observation, we conducted a pharmacoactivity assessment using an in vivo system with various concentrations ranging from 1 mM to 100 mM. On each designated post-operative day, animals were euthanized using CO2 asphyxiation. Mice were euthanized by gradual exposure to CO2 at a displacement rate of 20–30% of the chamber volume per minute. The distal nerve segments were collected for further analysis. Intact sciatic nerves from uninjured mice served as controls.

For ex vivo experimentation, sciatic nerve explant cultures were established based on a previously reported protocol [9]. In brief, sciatic nerves were aseptically isolated from 5-week-old male C57BL/6 mice using fine iris scissors (Fine Science Tools, Foster City, CA, USA) under sterile surgical conditions. The connective tissue surrounding each nerve was carefully removed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, #10010-023, Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) under a stereomicroscope to ensure clean isolation. The nerves were then cut into 3–4 segments, each measuring approximately 2–3 mm in length, using the same fine scissors. The dissected nerve pieces were transferred to Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; #SH30243.01, HyClone, Logan, UT, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, #16000-044, Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (#15140-063, Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Cultures were maintained with or without Flavo for three days in a humidified incubator at 37 °C and 5% CO2.

Tissue sections and teased nerve fibers were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA, #158127, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), rapidly frozen using dry ice, and cryosectioned into 6 µm slices. For immunostaining, the slides were incubated with 10% bovine serum albumin (BSA, #37525, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) for 1 hour at room temperature to block nonspecific binding sites. Subsequently, primary antibodies were applied and incubated overnight at 4 °C in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) supplemented with 2% BSA. After thorough PBS washes, sections were exposed to Alexa Fluor 488- or 594-conjugated secondary antibodies for 2 hours at room temperature. Fluorescence imaging was performed using a laser scanning confocal microscope (LSM700, Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). For quantitative evaluation, we acquired six randomly selected fields per slide using the confocal microscope (LSM 700, Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany). Each field was captured as a single focal plane (not z-stack images). The total number of images analyzed per experimental group was 36 images from 6 slides, and all images were processed and quantified using the same parameters to ensure consistency.

Proteins were extracted and lysed in a buffer containing 2% (#L3771, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and 1% protease inhibitor cocktail (#11697498001, Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Nutley, NJ, USA). To assess protein integrity, samples were resolved on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. Following electrophoretic separation, proteins were transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (#10600023, Amersham Biosciences, Buckinghamshire, UK). Membranes were then blocked overnight at 4 °C using 5% non-fat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween-20 (TBST, #7949, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Subsequently, membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies using goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP (#sc-2005), goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP (#2004) and mouse anti-goat IgG-HRP (#sc-2354) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA) for signal detection.

To assess the morphological extent of PNP, four indices were utilized: strip, ovoid, myelin, and neurofilament (NF) indices. The strip index was defined as the count of black or white transverse bands observed within a 500 µm segment of sciatic nerve explants under a stereoscopic microscope. The ovoid index referred to the number of myelin ovoids identified within a 200 µm region of a single teased nerve fiber using differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy (ZEN 2.3, Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH, Jena, Germany). The myelin index represented the proportion of teased nerve fibers among a total of 100 that retained continuous myelin staining exceeding 50 µm in length. The NF index denoted the number of nerve fibers exhibiting uninterrupted neurofilament-positive axonal segments of at least 100 µm in length, out of 100 fibers analyzed per sample [8].

All data are presented as mean

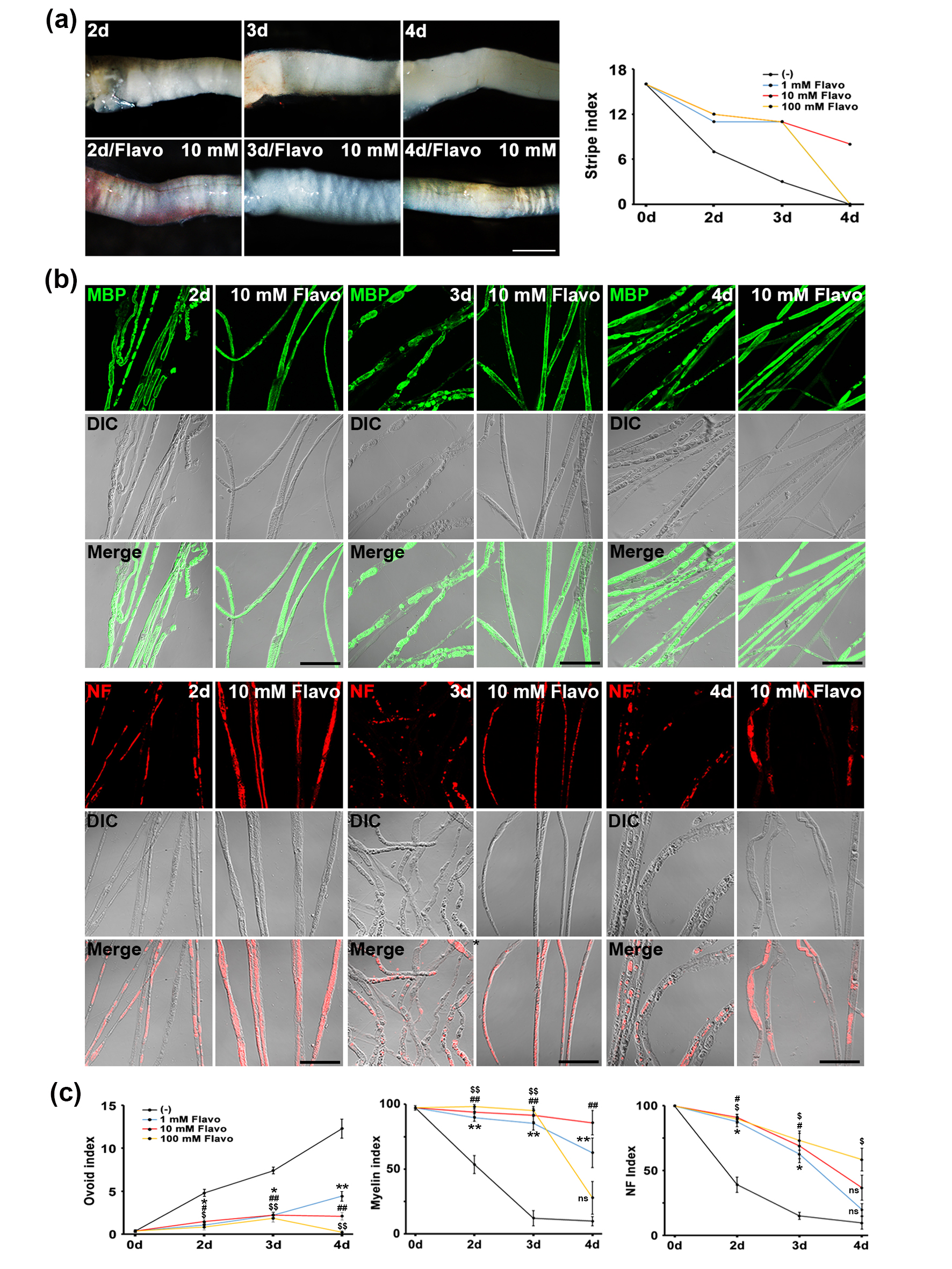

During PNP, the transverse stripes (bands of Fontana) in sciatic nerves disappeared on day 3 after nerve injury [8]. With this gross property, we performed a pharmacoactivity using an in vivo system and various concentrations (1 mM~100 mM) [8]. Among the concentrations, Flavo associated with the CDK signaling pathway significantly inhibited the disappearance of the transverse stripes in sciatic nerves at 3 and 4 days after axotomy (Fig. 1). A toxic effect of 100 mM of Flavo caused the death of Schwann cells; therefore, the stripe index decreased (Fig. 1, left panel). Thus, we used 10 mM of Flavo for further in vivo evaluation.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Flavo inhibits the disappearance of transverse stripes during in vivo PNP. (a) Dose-dependent treatment for showing transverse stripe patterns in sciatic nerves (left panel). Scale bar = 600 µm. Quantitative data (right panel) shows the disappearance patterns of transverse stripe under a stereoscope (n = 3 mice). (b) Confocal images show immunolabeling for myelin basic protein as a myelin marker (green; upper panel) and neurofilament as an axon marker (NF, red; lower panel). Scale bar = 100 µm. (c) Ovoid (left panel), myelin (middle panel) and NF (right panel) indices show quantitative degree of in vivo PNP (n = 4 mice). *, # or $p

PNP is characterized by two primary morphological features: demyelination and axonal degradation. To evaluate whether Flavo can suppress these pathological changes, we conducted immunofluorescent staining using antibodies against myelin basic protein (MBP), a marker of the myelin sheath, and neurofilament (NF), a structural axonal marker, in an established in vivo PNP model. In uninjured control sciatic nerves, MBP staining appeared as continuous linear signals along the nerve fibers. By contrast, sciatic nerves examined 3 days post-injury exhibited fragmented MBP signals with irregular boundaries, indicative of Schwann cell demyelination during PNP (Fig. 1b, upper panel). Remarkably, treatment with Flavo preserved the structural integrity of MBP staining at day 3, resembling the intact and linear appearance observed in controls. Following peripheral nerve injury, axonal degradation can result either from intrinsic self-destructive mechanisms or secondary to Schwann cell disintegration [1]. In control samples, NF staining was detected as uninterrupted red fluorescence within the longitudinal axis of nerve fibers (Fig. 1b, lower panel). However, nerves examined 3 days after injury showed a notable increase in interrupted or fragmented NF signals, suggesting significant axonal breakdown. Importantly, Flavo prevented such disruption, maintaining the continuity of NF staining comparable to uninjured nerves.

To quantify these morphological effects, we employed validated morphometric parameters, namely the ovoid (left panel) and myelin (middle panel) indices (reflecting demyelination) and the NF index (reflecting axonal integrity, right panel) [8]. Analysis revealed that Flavo treatment led to a time-dependent reduction in both demyelination and axonal degeneration, as demonstrated by improvements in all three indices (Fig. 1c). Collectively, these findings support the conclusion that Flavo exerts robust protective effects on myelin and axonal structure during in vivo PNP.

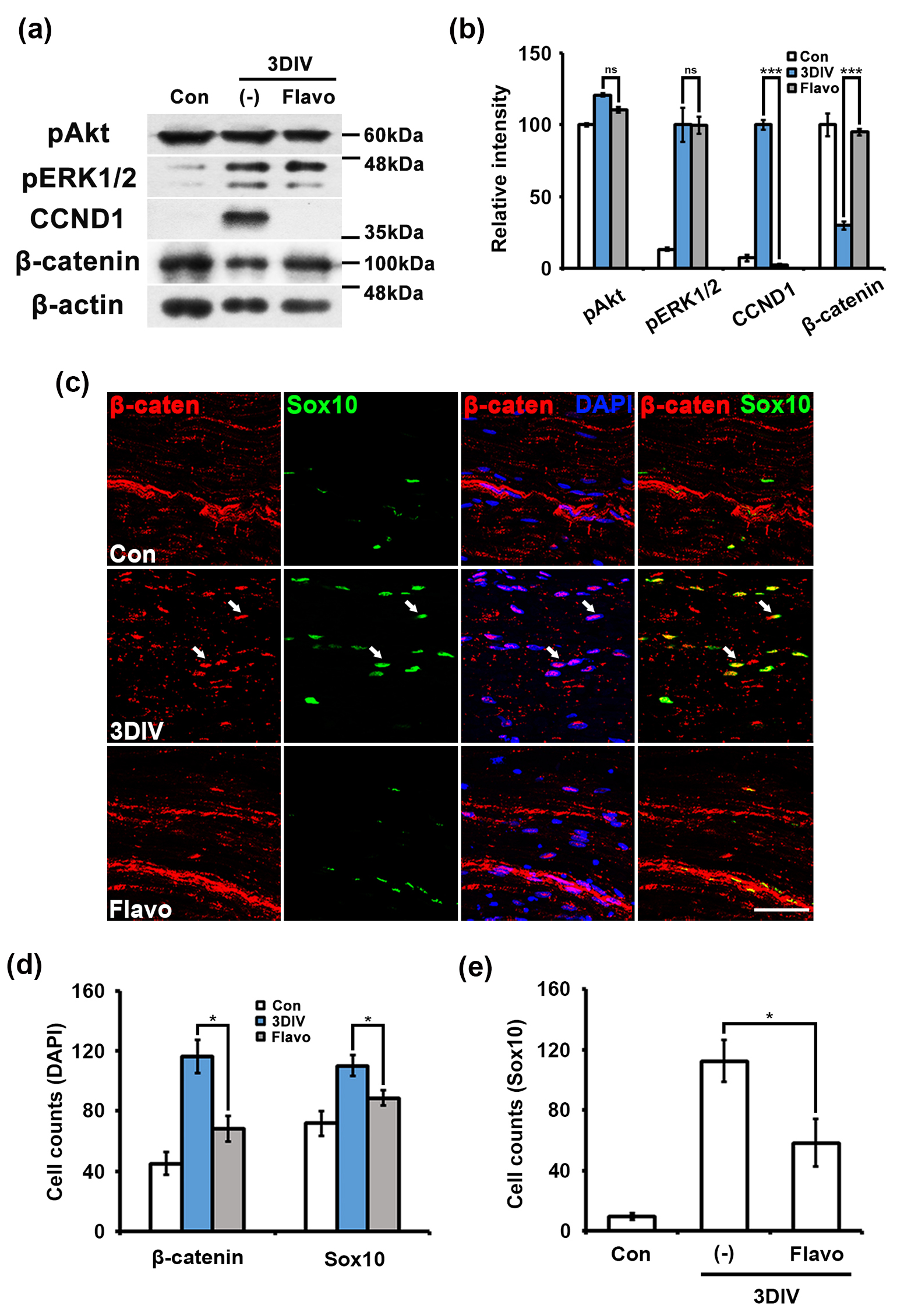

Various signaling pathways affect Schwann cell dynamics during PNP. To determine which signaling pathways are involved downstream of H2S in Schwann cells and whether Flavo regulates these signaling pathways during PNP, we checked the PI3K-Akt [10, 11], MAPK [12], and Wnt/

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Flavo inhibits the nuclear translocation of

The Wnt/

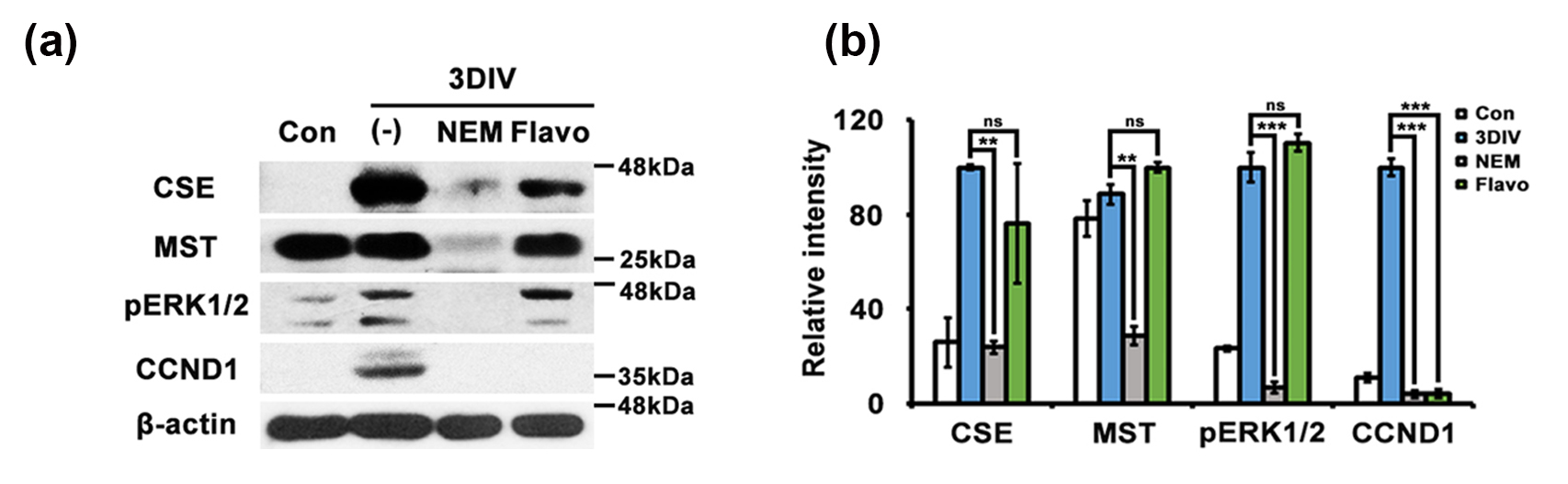

Additionally, because Flavo is an inhibitor of CDKs, which act downstream of H2S and induce cell cycle arrest and reduces cyclin D1 [7, 15, 16], Flavo should not inhibit upstream of CDKs, particularly CSE and 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase (MST) as a specific enzyme that produces H2S in Schwann cells [8]. To determine whether Flavo specifically modulates downstream targets of the H2S pathway during PNP, we performed western blotting using anti-CSE and anti-MST antibodies in an ex vivo model. N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), a specific H2S inhibitor [8], significantly reduced the expression levels of CSE and MST at 3DIV compared to untreated nerve fibers. In contrast, Flavo did not prevent the reduction in CSE and MST expression in degenerating Schwann cells (Fig. 3a,b), suggesting that CDK signaling acts downstream of the H2S pathway. Taken together, these findings demonstrate that Flavo effectively suppresses PNP through modulation of the H2S/

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Flavo fails to suppress the H2S signaling pathway during ex vivo PNP. (a) Protein lysates (30 µg) from sciatic explants cultured for 3DIV were analyzed by Western blotting (n = 4 mice). DIV, days in vitro; pERK1/2, phosphorylated extracellularregulated kinase 1/2; CCND1, cyclin D1; cystathionine

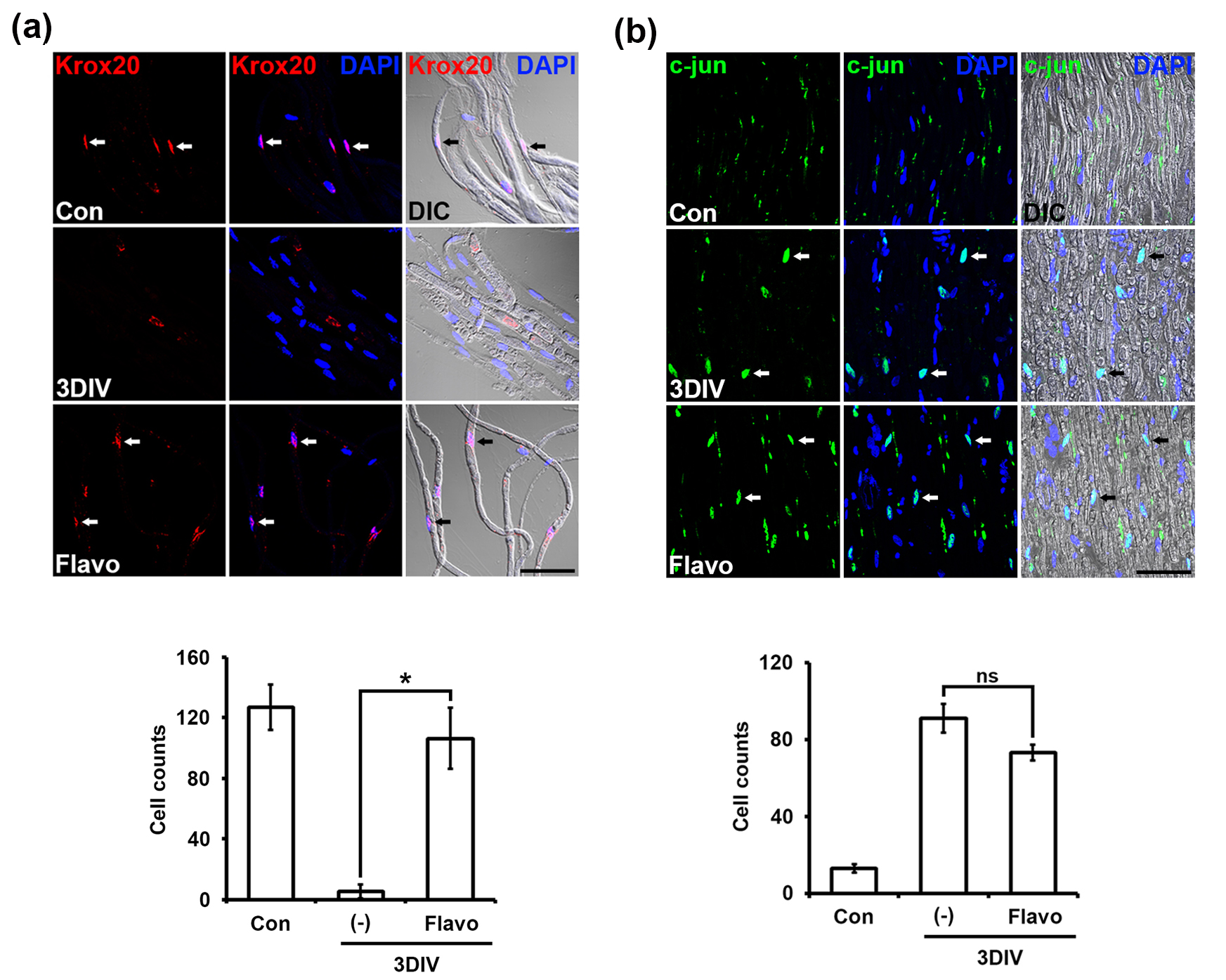

Transcriptional regulation in Schwann cells is an essential control tower to exhibit the phenotypes under both normal and degenerating conditions [3]. To assess whether Flavo affects transcriptional regulation during PNP, we checked two transcription factors, such as c-Jun and Krox20, as negative and positive regulators of myelin maintenance, respectively, and performed immunostaining with specific anti- c-Jun and Krox20 antibodies. Krox20 was expressed on the nucleus in Schwann cells from control nerve fibers but did not appear in Schwann cells at 3DIV. Flavo effectively protected the disappearance of Krox20 signaling in Schwann cells at 3DIV (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Flavo controls transcriptional regulation in Schwann cells during ex vivo PNP. (a) Confocal images show immunolabeling for Krox20 (red, upper panel). DAPI are used for a nucleus marker (blue). Arrows indicate nuclei double-positive for Krox20 and DAPI. Scale bar = 100 µm. The number of cells was counted with krox20 immunolabeling out of 200 DAPI-(+) nuclei in teased sciatic nerve fibers as compared with that of the control (lower panel, n = 4 mice). *p

In contrast, c-Jun was not expressed under normal conditions but was highly expressed on the nucleus in untreated Schwann cells at 3DIV (Fig. 4b). Flavo-treated nerve fibers showed no change in c-Jun nuclear expression in Schwann cells at 3DIV compared with that of untreated fibers at 3DIV (Fig. 4b). Taken together, these data indicate that Flavo effectively controls Krox20 expression as a positive transcriptional regulator to maintain myelin structure in Schwann cells in a c-Jun-independent manner.

H2S functions as an antioxidant to reduce oxidative stress in living cells [17]. Thus, most of its downstream molecules are involved in overcoming oxidative stress and a return to normal conditions [17]. In previous studies, H2S regulated cyclin D1 expression, and cyclin D1 protein levels were regulated by

Peripheral nerves exhibit morphological and biochemical phenotypes, such as demyelination, axonal degradation, transcriptional regulation, Schwann cell trans-dedifferentiation, and Schwann cell proliferation during PNP. In our study, Flavo significantly inhibited morphologically these phenotypes and arrested PNP (Fig. 1). Schwann cells revert to a dedifferentiated form during PNP, which is also observed in immature Schwann cells during their development [3]. During PNP, axon degradation is regulated both physically and biochemically by Schwann cells [1]. Once PNP begins to progress, dedifferentiating Schwann cells physically dismantle and dissolve axons, thereby inducing axon degradation, while the myelin within Schwann cells undergoes fragmentation mediated by both Schwann cells by itself and macrophages infiltrating from outside of the nerves. Therefore, the effect of Flavo is thought to suppress axon degradation indirectly, rather than directly, by inhibiting CDKs in Schwann cells. In particular, Flavo possesses a potent ability to effectively suppress in vivo PNP, suggesting its potential for clinical application (Fig. 1). This suggests that Flavo can effectively penetrate the blood-nerve barrier (BNB), which protects peripheral nerves [19], thereby enabling control of in vivo PNP.

Oxidative stress induces c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) activation in several cell types [20] and its inhibitory effect protects c-jun phosphorylation, leading to suppressed c-jun transcriptional activity. In our study, we determined that Flavo did not affect p-c-jun expression in Schwann cells during PNP while Krox20 (Erg2), as a positive regulator of myelin maintenance, was expressed in Flavo-treated Schwann cells at 3DIV (Fig. 4). A previous study reported that P-TEFb p-Tefb affects Krox20 gene expression [21]. Thus, Flavo could canonically affect the transcriptional function of P-TEFb during PNP and subsequently inhibit the decrease in krox20 expression by inactivated P-TEFb, leading to suppressed PNP. In other words, no change in krox20 expression in Flavo-treated Schwann cells could maintain the structure of the myelin and evoke saltatory conduction.

Collectively, our findings demonstrate that Flavo exerts a significant inhibitory effect on PNP. Our PNP models revealed that Flavo attenuates hallmark pathological phenotypes, including in vivo Schwann cell demyelination and axonal degeneration, as confirmed by morphometric analysis. Mechanistically, Flavo appears to act through modulation of the H2S/

Flavo significantly modulates transcriptional activity in Schwann cells by regulating the complementary roles of c-Jun and Krox20 during PNP. In vivo, Flavo dose-dependently attenuated demyelination and axonal degeneration. Mechanistically, Flavo inhibited the H2S/

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conceptualization, HJC, NYJ and JJ; methodology, HJC, NYJ and JJ; software, JL; validation, HK and K-JS; formal analysis, HJC, NYJ and JJ; investigation, JJ; resources, NYJ; data curation, HJC; writing—original draft preparation HJC, NYJ and JJ; writing—review and editing, HJC, NYJ and JJ; visualization, NYJ; supervision, JJ and NYJ; project administration, JJ; funding acquisition, HJC, NYJ and JJ. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

All procedures in the mouse experiments were conducted in accordance with the Kyung Hee University Committee on Animal Research guidelines, with approval, ensuring efforts to minimize both animal suffering and the number of animals used [Protocol number #KHSASP-21-463].

We would like to thank Muwoong Kim (Kyung Hee University, Korea) for his valuable help and suggestions.

This work was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning, No. 2021R1A2C1004184 (to H-.J.C), No. 2021R1A2C1004133 (to N.Y.J.) and No. 2023R1A2C1003763 (to J.J.).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.