1 Biology Department, College of Science and Humanities–Al Quwaiiyah, Shaqra Univeristy, 19257 AlQuwaiiyah, Saudi Arabia

Abstract

Aerococcus urinae is an emerging pathogen associated with serious infections, particularly in immunocompromised individuals; however, no approved vaccines or targeted therapies currently exist. Thus, this study presents the rational design of a novel multi-epitope chimeric vaccine using integrative core-subtractive proteomics and advanced immunoinformatics.

Two conserved antigenic targets (cell division protein, filamenting temperature-sensitive protein Z (FtsZ), and single-stranded DNA-binding protein) were identified for epitope prediction through Geptop 2.0 essentiality screening, basic local alignment search tool for proteins (BLASTp) non-homology analysis against the human proteome, subcellular localization filtering using the subcellular localization predictive system (CELLO), and antigenicity scoring with VaxiJen (threshold ≥0.5). The final construct incorporated the carefully selected B cell, cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL), and helper T lymphocyte (HTL) epitopes to maximize immunogenicity and population coverage.

Comprehensive analyses demonstrated the stability, antigenicity, non-allergenicity, non-toxicity, and cytokine-inducing potential of the vaccine. Molecular docking and dynamics simulations confirmed strong binding affinity and structural stability with toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), underscoring the ability of the vaccine to trigger innate immune activation. In silico cloning and codon optimization predicted efficient expression in Escherichia coli K12. Immune simulations further supported robust humoral and cellular responses.

These findings highlight a promising vaccine candidate warranting experimental validation as a potential strategy to protect against A. urinae infections.

Keywords

- Aerococcus urinae

- chimeric vaccine

- immunoinformatics

- epitope mapping

Aerococcus urinae is a Gram-positive coccus that usually occurs in pairs or short chains. Aerococcus urinae displays alpha-hemolysis on blood agar [1]. Moreover, Aerococcus urinae does not produce pyrrolidonyl aminopeptidase and is catalase-negative [1]. A. urinae was first reported in 1967, where this organism was assumed to be an innocuous urinary contaminant, with no clinical significance [2]. However, A. urinae has since been identified as a serious pathogen, especially in older men with underlying medical disorders [3]. Although A. urinae is most commonly responsible for urinary tract infections (UTIs), this organism can also result in more severe side effects, including bacteremia, endocarditis, soft tissue infections, osteomyelitis, spondylodiscitis, and urosepsis [4]. Typically, this bacterium is sensitive to antibiotics such as penicillin, amoxicillin, and nitrofurantoin; however, A. urinae is resistant to sulfonamides and other commonly prescribed antibiotics, including trimethoprim and fluoroquinolones [2]. Thus, due to multidrug resistance, the infections caused by this bacterium are increasing [5]. Hence, urine cultures should include antibiotic susceptibility testing due to the increased prevalence of antibiotic resistance. The correct identification and treatment of diseases associated with this organism cannot be overemphasized, considering that A. urinae has become a major pathogen [6]. Accordingly, effective vaccine candidates and new imaginative therapeutic approaches are urgently needed. The recent advancement in sequencing technologies has provided sufficient genetic information, while this surplus has made screening novel targets for vaccinations easier [7]. Indeed, several vaccine candidates have been developed for a wide range of diseases through the advancement of subtractive proteomics and immuno-informatic approaches [8].

Recombinant DNA-based vaccines, as the new generation, offer several advantages over traditional vaccinations, such as enhanced protection and reduced pathogenicity [9]. Thus, recombinant vaccines provide a powerful replacement for conventional immunization methods [9]. A multi-epitope vaccine (MEV) is a well-known type of recombinant vaccination aimed at enhancing immune reactions against various diseases [10]. Immunogenic proteins create several epitopes used in this MEV to provoke a highly active immunological response [11]. For example, B cell, T cell, and interferon gamma (IFN

Therefore, this study aimed to identify an effective multi-peptide subunit vaccine that can specifically target A. urinae. We performed a series of computational analyses, including molecular docking and molecular simulation assays. Our methodology involved the screening of the proteome to identify vaccination targets that could elicit a good immune response. Furthermore, this study aimed to identify epitopes that may result in good immunogens. Subsequently, we chose the epitopes based on high antigenicity and that do not evoke allergenicity, non-toxicity, or positive scores on immunogenicity. To enhance the immunogenicity of the MEV, an adjuvant was also added to the N-terminal of the antigenic epitope. Moreover, appropriate linkers were used to connect the epitopes. The physicochemical, structural, and immunological properties of the vaccine construct were then studied using a variety of bioinformatics methods. Additionally, the chimeric vaccine sequence was codon-optimized to ensure that the sequence is expressed effectively in Escherichia coli.

The A. urinae Culture Collection, University of Gothenburg (CCUG) 59500 (UniprotID_UP000008129) sequence was downloaded from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) [13]. Essential proteins were identified from the whole proteome using Geptop 2.0 server (Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China) [14]. To minimize the risk of autoimmune reactions, BLASTp analysis against the human proteome was performed, and only non-homologous proteins were considered [10, 15]. The subcellular localization of the filtered proteins was then predicted using the CELLO server 2.5 (SubCELlular LOcalization Predictor, National Cheng Kung University, Taiwan), and only extracellular and membrane-associated proteins were retained as potential vaccine targets, while cytoplasmic proteins were excluded [16]. The antigenicity of the selected proteins was calculated using a threshold value of 0.5 in the VaxiJen server Version 2.0 (Center for Vaccine Design, University of Oxford, UK, http://www.ddg-pharmfac.net/vaxijen/VaxiJen/VaxiJen.html) [12, 17].

Cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) are crucial for initiating immunity and antigen recognition [18]. This study used the CTLPred server (Institute of Microbial Technology (IMTECH), Chandigarh, India, https://npsa-prabi.ibcp.fr/) to predict major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I epitopes [19]. Therefore, prompting cytotoxic T cell responses was considered [18]. For vaccine construction, epitopes were selected based on consensus score. This method was employed to improve the predictability by incorporating both sequence-based and structure-based data. This is necessary to identify epitopes that exhibit high binding affinity to MHC-I molecules [20]. Immunogenic potential of the chosen epitopes was determined using the VaxiJen 2.0 server, which follows a machine-learning algorithm [21]. Only epitopes validated as non-toxic and non-allergenic were included in the final vaccine construct to ensure safety and efficacy via AllerTOP 2.0 (Institute of Microbiology, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Bulgaria, https://npsa-prabi.ibcp.fr/) and ToxinPred servers (IMTECH, Chandigarh, India, https://npsa-prabi.ibcp.fr/) [22, 23].

Helper T lymphocytes (HTLs) induce adaptive immunity [19]. Being strong activators of the immune system, HTL epitopes that bind to MHC alleles are used for vaccine development [13]. HTLs are critical for the production of antibodies that identify and neutralize pathogen-associated antigens by cross-reacting with B cells. Importantly, MHC class II molecules can be used to predict these epitopes [21]. This interaction is immune system-dependent because HTLs work together with macrophages and CTLs to develop a strong defense against infections [15]. The three immune cells synergize to coordinate a comprehensive response that effectively identifies, neutralizes, and clears dangerous infections by underlining the relevance of HTL epitopes to the formulation of vaccines [24].

Since B cell epitopes are crucial in the elicitation of adaptive immunity, these cells were also included in the vaccine design [25]. ABCPred Version 2.0 (IMTECH, Chandigarh, India, https://webs.iiitd.edu.in/raghava/abcpred/) has also been used for the prediction of B cell epitopes. One of the many bioinformatics tools designed to find linear B cell (LBL) epitopes identifies an antibody-binding site in protein sequences [26]. The term “epitope” describes a region in proteins to which antibodies have been shown to attach and that are involved in adaptive immunity [26]. A threshold of 0.05 was applied to ABCpred to increase the likelihood that the B cell epitopes identified in our current investigation are correct [11]. In addition, the Immune Epitope Database (IEDB) analysis tools were employed to improve the characterization of the predicted B cell epitopes [27]. Parameters such as antigenicity, hydrophobicity, surface accessibility, and flexibility were assessed to ensure that only the most immunogenic and accessible epitopes were selected for inclusion in the final vaccine construct.

MEV sequences were combined using specific peptide linkers to join particular epitopes, such as a CTL, HTL, and an adjuvant, to enhance the immunological response. Based on careful considerations, an adjuvant was selected that would optimize and modulate the immune response [28]. Due to the known potent immunostimulatory activities, cholera toxin subunit B (CTB) was chosen as the adjuvant [29]. Subsequently, CTB was conjugated at the N-terminal to the vaccine construct using a glutamic acid–alanine–alanine–alanine–lysine (EAAAK) linker that favors structural stability and efficient adjuvant separation from the epitopes [30]. Indeed, linkers were strategically used to provide functional isolation, ensuring that each epitope achieved optimal performance and immunogenicity [15]. The alanine–alanine–tyrosine (AAY) linker and the glycine–proline–glycine–proline–glycine (GPGPG) linker were utilized to connect the CTL and HTL epitopes, respectively, since these are perfectly suited to preserve the T cell epitope and the independent functioning [15]. Analogous to this, the linear B-cell (LBL) epitopes were joined using the GPGPG linker, while lysine–lysine (KK) linkers were applied as short spacers between epitope blocks to retain their independent immunogenic response [31]. The stepwise construction of the components enhances the immunological efficacy of the vaccine, ensuring proper stimulation of both humoral and cellular immunity [19].

The final MEV sequence was tested against the human proteome for minimal homology to avoid any autoimmune reactions [32]. The VaxiJen and IEDB servers 2024 release (Immune Epitope Database, La Jolla Institute for Immunology, CA, USA, https://npsa-prabi.ibcp.fr/), already well-known for their ability in the evaluation of protein sequences for their immune-stimulating potential, have also been used to analyze the immunogenicity and the antigenic profile of the MEV sequence [13]. The ProtParam server (ExPASy Bioinformatics Resource Portal, Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics, Switzerland, https://npsa-prabi.ibcp.fr/) was also used to calculate the physicochemical properties of the modified vaccine [33]. Moreover, the ProtParam server was used to compute characteristics of the vaccine [33]. All harmful and allergenic constituents in the vaccine were tested for safety. Server ToxinPred was utilized for the toxicity prediction, and server AllerTOP 2.0 was applied to predict allergenicity [31, 34]. Among the candidates entering the vaccination process, only those considered non-toxic and non-allergic were considered, ensuring both immunogenic efficacy and safety [19].

The secondary structure of the MEV construct, including alpha helices, beta sheets, coils, and extended chains, was predicted using a self-optimized prediction method with the alignment (SOPMA) tool (Version 2.0, Network Protein Sequence Analysis, Institut de Biologie et Chimie des Protéines (IBCP), France, https://npsa-prabi.ibcp.fr/) [35]. The SOPMA tool formulates its predictions based on an analysis of the primary sequence, anticipating the composition and order of the structural features. This approach provides useful insight into the structural stability and feasible functional conformations of the vaccine by understanding how the epitopes might interact within the immune system, ensuring the overall stability and efficacy of the construct [36].

A multi-step procedure was used to evaluate and optimize the three-dimensional (3D) structure of the MEV, in an error-free and useful manner, as described previously [22]. The first 3D model of the vaccine component was prepared using the AlphaFold 2 server (DeepMind Technologies, London, UK, http://galaxy.seoklab.org/). AlphaFold 2 is accurate in predicting protein structures, including complex multi-domain examples [37]. The GalaxyRefine server (Seoul National University, Korea, http://galaxy.seoklab.org/) enhances the quality of predicted protein structures by optimizing geometry and predicting 3D conformations, bringing the model as close as possible to the native protein structure. This process requires side-chain refinement and further overall structural relaxation, thereby maximizing both local and global accuracy [38]. The Ramachandran Plot Assessment Tool (RAMPAGE), Saves 6.1 (Structural Bioinformatics Group, University College London, UK), is used for validating the stereochemical quality of the resulting protein model. Then, the quality of the improved structure should be evaluated. For this purpose, factors such as bond angles and dihedral angles are examined to ensure that the structure aligns with the anticipated physical and chemical behavior within restrictions [39]. This is the step during which the stability and reliability of the model are validated [13].

To design the MEV, the ElliPro (Immune Epitope Database, La Jolla Institute, CA, USA, https://tools.iedb.org/ellipro/) algorithm incorporates discontinuous B cell epitopes that are crucial to the recognition by the antibodies [40]. Since the tool relies on input from the tertiary structure of the vaccine construct, this algorithm recognizes putative discontinuous B cell epitopes that do not appear to be continuous in sequence but are joined in the 3D protein structure [13]. ElliPro is employed to calculate the isoelectric point (pI) score for each predicted epitope. Higher values indicate greater accessibility at the surface and a better chance for involvement in antibody binding [41]. The pI score measures how accessible a particular residue in the protein is on the surface. Epitopes, which involve non-sequential residues and have higher PI scores, are relevant targets for immune recognition and activation since epitopes are noted to interact with the immune system more effectively [42]. Indeed, this knowledge is required to develop vaccines seeking to elicit potent and targeted antibody responses [42]. Thus, optimizing the MEV construct to improve interactions with the immune system may enhance the potential for protective efficacy by identifying accessible and immunologically significant B cell epitopes [36].

The docking analysis was used to identify the potential for interactions between the MEV and human immune receptors [43]. Among the receptors studied, Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) is a crucial component in the innate immune system, specifically a pattern recognition receptor involved in recognizing microbes on the surfaces of most organisms. TLR4 is a member of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) [44], including lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and lipooligosaccharide (LOS). Moreover, activation of TLR4 is necessary to cause immunological reactions and fight infections [45]. The TLR4 structure retrieved from the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID: 2Z66) was chosen as the receptor for molecular docking analyses.The ClusPro server Version 2.0 (Boston University, MA, USA, https://cluspro.bu.edu/) was utilized to conduct the MEV docking simulation with TLR4 [46]. ClusPro is a widely used bioinformatics tool that predicts the most likely binding conformations of protein–protein complexes using fast Fourier transform (FFT) correlation algorithms [46]. Therefore, this docking study aimed to identify the specific contact and potential binding affinity of the MEV construct with TLR4, elucidating how the vaccine can trigger the immune response through TLR4-mediated pathways [47].

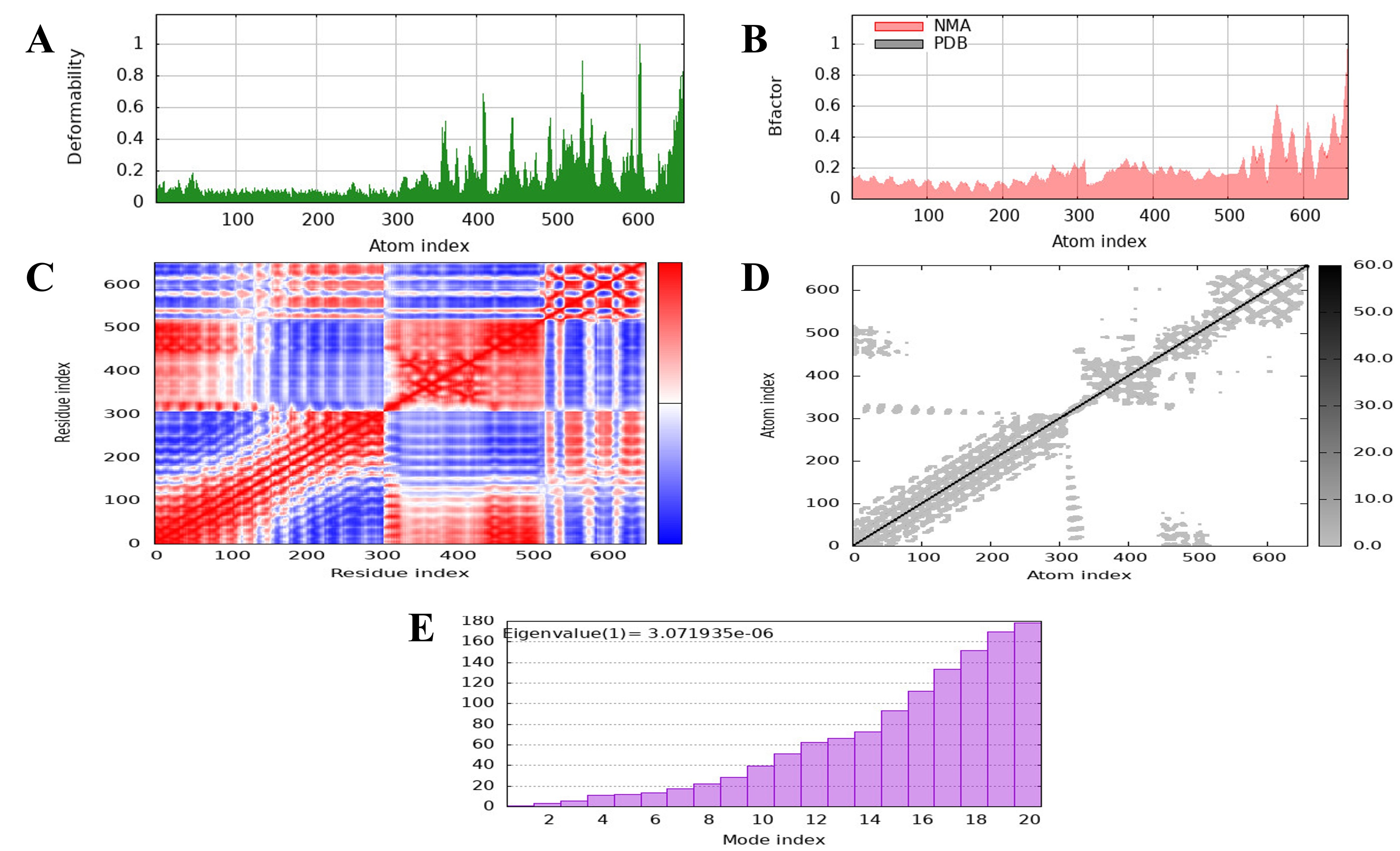

The present study attempted to estimate the stability of the protein–protein complex between the MEV and the TLR4 receptor, through a normal mode analysis (NMA) [22]. Indeed, NMAs are helpful in explaining the dynamics of behavior and stability, as well as the adaptability of protein complexes in a changing environment [48]. This was accomplished by performing a normal mode evaluation on the iMODS (NMA) server (National Autonomous University of Mexico; https://imods.chaconlab.org/) [49]. The server assessed the eigenvalue, covariance, B-factors, and deformability of the protein complex, among other dynamic characteristics [49]. Eigenvalues are utilized to measure the stiffness in motion; a structure with a smaller eigenvalue is more pliable and deformable [13]. B-factors are averages of flexibility at each residue position, while a covariance analysis provides information about correlated movements between different subunits in the complex [19]. Furthermore, the deformability of the main chain was estimated, which describes how easily a region or residue can bend or distort in response to external forces [50]. Further, an NMA helps to determine the energy landscape of the complex and can provide crucial information about the general stability and flexibility of the MEV–TLR4 interaction [43]. This analysis can predict the quality of the vaccine design by how well the stability and functional conformation are maintained after immune activation [13].

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were performed using the Groningen Molecular Dynamics Simulation Package (GROMACS, https://www.gromacs.org/) to investigate the dynamic stability and interaction pattern of the vaccine–receptor docked complex [51, 52]. The top-ranked docking conformation was used as the starting structure for the subsequent analysis. Sodium and chloride ions were added to a final concentration of 150 mM to simulate physiological ionic conditions [53]. The system was relaxed under energy minimization using the steepest descent algorithm until the maximum force converged to below 10 kJ/mol, verifying system stability [54]. The bond constraints were addressed using the LINCS algorithm; meanwhile, long-range electrostatic interactions were treated with the Particle Mesh Ewald method, using a cutoff of 0.9 nm for both Coulombic and van der Waals interactions [55]. Equilibration was conducted in two successive stages. First, a 100 ps constant number of particles, volume, and temperature (ensemble) (NVT) ensemble simulation was performed to equilibrate the system temperature by maintaining a fixed particle number and volume. Next was a 300 ps constant number of particles, pressure, and temperature (ensemble) (NPT) ensemble simulation, keeping particle number, temperature, and pressure fixed to equilibrate system density. Periodic boundary conditions were applied in all three spatial directions to prevent boundary artifacts [56, 57]. The production run of the MD simulation was then performed, and the trajectories were processed with the help of integrated GROMACS utilities [58]. Post-processing, which involved trajectory visualization and statistical plotting, was additionally performed in Python Version 3.8 (Python Software Foundation, DE, USA) using Matplotlib [59]. This multi-step protocol allowed for the detailed analysis of conformational dynamics and insight into the binding orientations of the most stable protein–protein complex.

In silico immune simulation was conducted using the C-ImmSim 10.1 server (Institute for Immunology and Bioinformatics, University of Genoa, Italy; http://kraken.iac.rm.cnr.it/C-IMMSIM/) to assess the potential immunogenicity of the MEV construct [19]. This server simulates immune system responses based on a simulation model resembling all vital organs that are pivotal in triggering both innate and adaptive immunity, such as the lymph node, bone marrow, and thymus [60]. The MEV construct is input into the server as a multi-protein text-based format for nucleotide/amino acid sequences (FASTA) file [13]. The simulation starts with the preset options, which contain just one injection dose (number = 1) with a volume of 10 and 100 steps, and the random seed is set at 12,345 for reproducibility. For simulating ordinary human genetic combinations, the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) alleles were assigned to A0101, B0702, and human leukocyte antigen-DR beta 1 (DRB1) 0101 [61]. The in silico simulation pre-validation of the vaccine efficacy in experiments provides significant insights into the mechanism of MEV in activating both humoral and cellular immune responses, such as the activation of cytotoxic T cells and the generation of antibodies [62].

Codon optimization was conducted in this study using the Java Codon Adaptation Tool (JCat, http://kraken.iac.rm.cnr.it/C-IMMSIM/) to improve the expression of the vaccine gene in Escherichia coli K12 [63]. The amino acid sequence was reverse-translated into a DNA sequence customized to match the codon usage preferences of E. coli. Parameters such as the codon adaptation index (CAI) [64] and guanine–cytosine (GC) content were assessed to promote efficient transcription and translation [65]. A high CAI value reflected good compatibility with the host system, while a balanced GC content contributed to a stable gene expression [8, 66]. The optimized sequence was then inserted into the pET30a(+) vector using SnapGene 3.2.1 (Version 3.2.1 GSL Biotech LLC, Chicago, IL, USA, https://www.snapgene.com/) for expression of the recombinant vaccine protein in E. coli [67].

The whole proteome of A. urinae CCUG 59500 comprises 1684 proteins. This led to the inference of 283 essential proteins as designated by the web server Geptop-2.0. To avoid the presence of human homologs and reduce the risk of autoimmune reactions, 127 non-homologous proteins were identified through BLASTp analysis. The CELLO server classified proteins into cytoplasmic, extracellular, and membrane-associated. Cytoplasmic proteins were excluded to avoid inaccessible targets, and only extracellular and membrane-associated proteins were retained as potential vaccine candidates, since surface-exposed antigens are more likely to trigger host immune responses. Subsequently, two extracellular proteins with zero transmembrane helices were selected from these and further evaluated for antigenicity (Table 1).

| Accession no. | Protein | Antigenicity | Allergenicity | Toxicity |

| |F2I5E0| | Single-stranded DNA-binding protein | 0.6372 | Non-allergen | Non-toxin |

| |F2I5S9| | Filamenting temperature-sensitive mutant Z protein (FtsZ) | 0.6430 | Non-allergen | Non-toxin |

A total of 15 CTL epitopes were identified in A. Urinae based on the selected proteins. From these 15, the top 7 were selected for further studies (Table 2). Additionally, 23 unique HTL epitopes were initially predicted, and from these, 4 final epitopes with the highest antigenicity and immunogenicity were selected for inclusion in the vaccine construct (Table 3). Meanwhile, 24 LBL epitopes were predicted, and from these, two with the best properties were selected (Table 4).

| Epitope | Protein | Allele | Position | Antigenicity | Immunogenicity |

| MDLEFDNTAEYN | Cell division protein FtsZ | HLA-B*18:01 | 1–12 | 1.3734 | 0.38342 |

| HLA-B*44:03 | |||||

| HLA-B*44:02 | |||||

| YENQQGQRVYVT | Single-stranded DNA-binding protein | HLA-B*40:02 | 82–93 | 1.2172 | –0.20131 |

| YRNAQGETQTDF | Single-stranded DNA-binding protein | HLA-C*07:01 | 37–48 | 1.1708 | 0.02945 |

| YVNLDFADVRTV | Cell division protein FtsZ | HLA-C*12:03 | 210–221 | 1.0996 | 0.28726 |

| GPKRGRAAAEGI | Cell division protein FtsZ | HLA-B*07:02 | 144–155 | 1.0116 | 0.28281 |

| NDRLDDEVVVTV | Cell division protein FtsZ | HLA-A*02:01 | 303–314 | 0.9926 | 0.28292 |

| TQSGTAVANFTV | Single-stranded DNA-binding protein | HLA-A*68:02 | 20–31 | 0.9638 | 0.24999 |

CTL, cytotoxic T lymphocyte; HLA, human leukocyte antigen.

| Epitope | Protein | Allele | Position | Antigenicity | Immunogenicity |

| VNIIFGTTINDRLDD | Cell division protein FtsZ | HLA-DRB1*01:02 | 294–308 | 0.8399 | 0.59694 |

| LVGRLTREVDLRYTQ | Single-stranded DNA-binding protein | HLA-DRB1*04:02 | 7–21 | 0.7941 | 0.35726 |

| HLA-DRB1*13:01 | |||||

| HLA-DRB1*13:27 | |||||

| HLA-DRB1*13:28 | |||||

| HLA-DRB1*08:04 | |||||

| HLA-DRB1*11:02 | |||||

| HLA-DRB1*11:21 | |||||

| HLA-DRB1*13:22 | |||||

| NNFSLLEPKSVTER | Single-stranded DNA-binding protein | HLA-DRB1*01:01 | 98–112 | 0.7728 | –0.30435 |

| SSEVNIIFGTTINDR | Cell division protein FtsZ | HLA-DRB1*01:02 | 291–305 | 0.7640 | 0.68232 |

DRB1, human leukocyte antigen-DR beta 1; HTL, helper T lymphocyte.

| Epitope | Protein | Score | Position | Antigenicity | Immunogenicity |

| VLVGRLTREVDLRYTQ | Single-stranded DNA-binding protein | 0.76 | 589 | 0.7506 | 0.39208 |

| FITAGMGGGTGTGAAP | Cell division protein FtsZ | 0.80 | 174 | 1.9521 | 0.20935 |

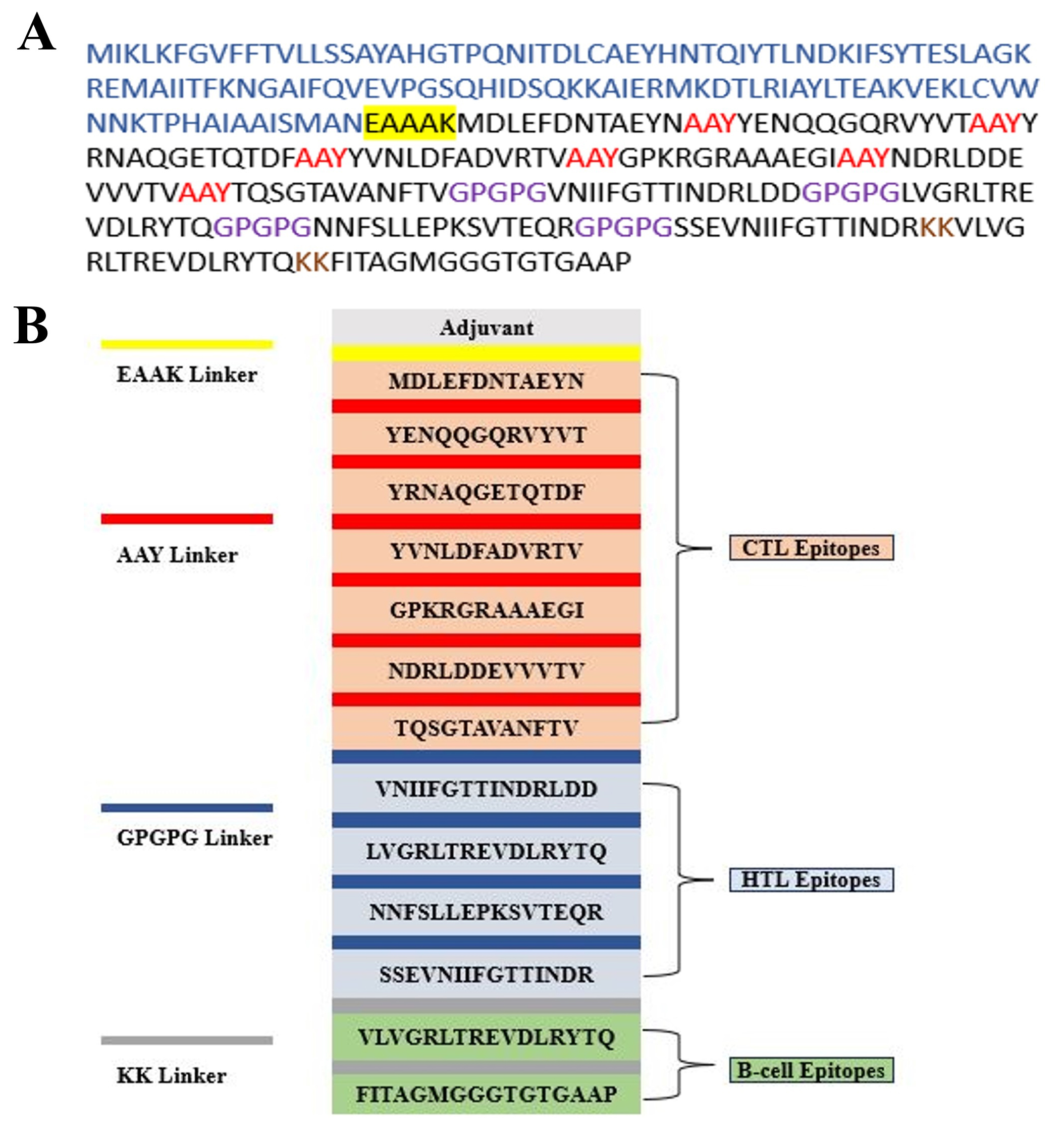

The selected MHC-I, MHC-II, and LBL epitopes were assembled into an MEV construct. These epitopes were linked via the AAY, GPGPG, and KK linkers to enhance epitope presentation and boost the immune response upon immunization. To further improve efficacy, the CTL epitopes were fused to CTB via an EAAAK linker, providing structural stability and preventing the formation of unwanted junctional epitopes. Therefore, the final design included 347 amino acids and was optimized for structural integrity and immunogenicity (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Schematic representation of the multi-epitope vaccine (MEV) construct and the component linkers. (A) The sequence was built based on several epitopes. The epitope sequence has a dark color. The adjuvant sequence is displayed in blue, the EAAAK linker is underlined in black, the AAY linkers are shown in red, the GPGPG connections are displayed in purple, and the KK linkers are displayed in brown. (B) The EAAAK (yellow) linker, which links the adjuvant at the N-terminal, is 1 of the 347 residues that form the final MEV. CTL epitopes are joined by the AAY linker (red), HTL and linear B-cell (LBL) epitopes are joined by the GPGPG linker (blue), while KK linkers (grey) are used as short spacers between epitope blocks. EAAAK (yellow) links the adjuvant at the N-terminal. EAAAK, glutamic acid–alanine–alanine–alanine–lysine; AAY, alanine–alanine–tyrosine; GPGPG, glycine–proline–glycine–proline–glycine; KK, lysine–lysine; MEV, multi-epitope vaccine; CTL, cytotoxic T lymphocyte; HTL, helper T lymphocyte.

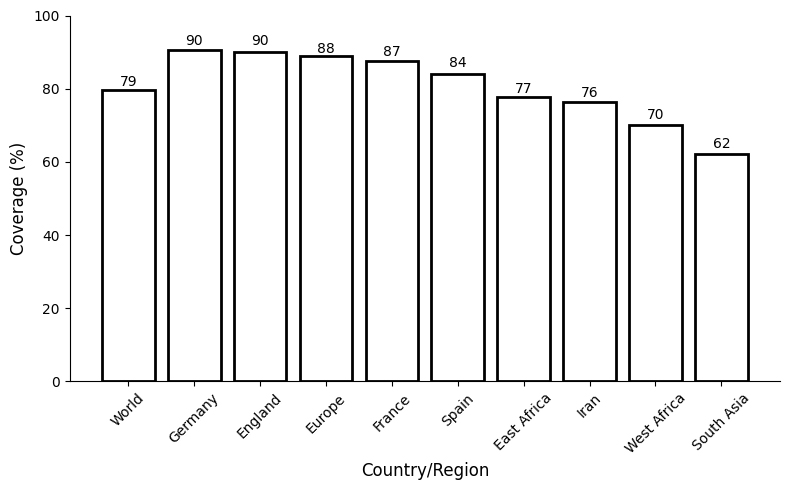

Coverage estimation is one of the important factors in designing an MEV. Thus, four HTL and seven CTL epitopes with individual alleles were chosen. The estimated population coverage from the statistical analysis of these epitopes was 79% of the global population. Both Germany and England reached peak population coverage levels at 90%. Meanwhile, France peaked at 87%, Spain at 84%, and an overall European coverage of 88%, while other European nations also exhibited strong coverage. These findings enhance the possibility of broad protection, as the data confirm that the filtered epitopes have wide applicability in the population and would be a good choice for developing an MEV (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. A complete evaluation of the population coverage of the chosen T cell epitopes.

The MEV construct was initially checked for similarity against the human proteome to minimize the chance of cross-reactivity; no significant homology was detected. The MEV construct was then assessed for toxicity, antigenicity, and allergenicity, confirming that the construct is highly antigenic, non-toxic, and non-allergenic. Analysis of the physicochemical properties using the ProtParam tool estimated the molecular weight of the MEV construct at 37.77 kDa, with a theoretical pI value of 6.46. The predicted half-life was around 30 hours in mammalian cells, more than 20 hours in yeast, and roughly 10 hours in E. coli, indicating good stability across various host systems.

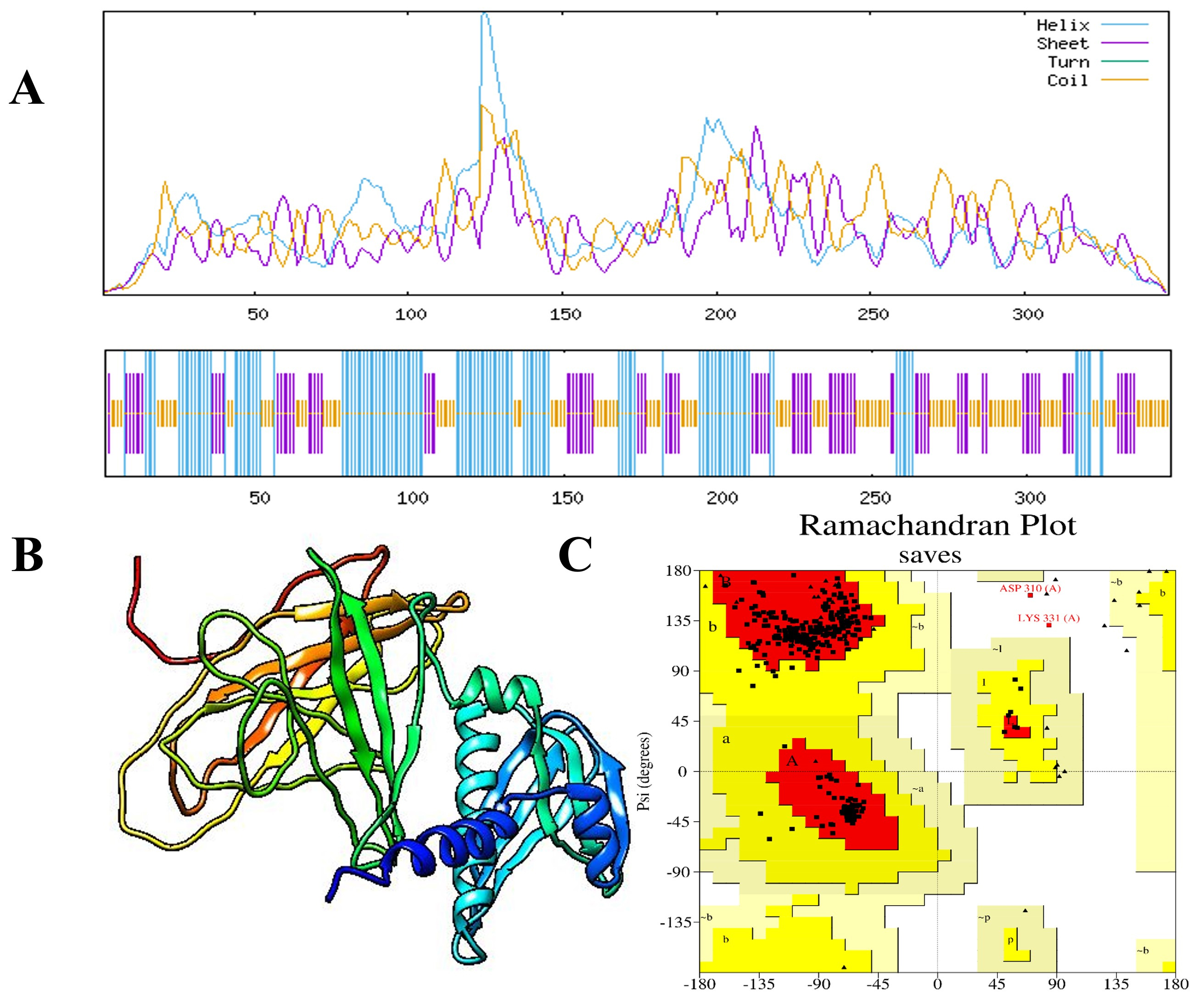

The SOPMA server was used to predict the secondary structure of the protein. The result of the research indicates that the MEV sequence comprises 96 amino acids that form beta-strands, 129 amino acids that form coils, and 122 amino acids that form alpha helices. The detailed secondary structure prediction yielded an alpha helix content of 35.16%, beta strands at 27.67%, and coils at 37.18% (Fig. 3A). This establishes that a well-balanced structural composition is indicative of the stability and immunogenic qualities of the vaccine.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Predicted secondary and tertiary structures of the MEV construct. (A) The secondary structure of the final MEV construct was predicted using the Self-Optimized Prediction Method with Alignment (SOPMA) technique. (B) The enhanced 3D structure of the vaccine construct, and (C) triangles represent residues in favored regions and squares denote residues in allowed regions of the Ramachandran plot, the plot shows that 94.6% of residues are in favored regions, 4.7% are in allowed regions, and 0.7% are outliers.

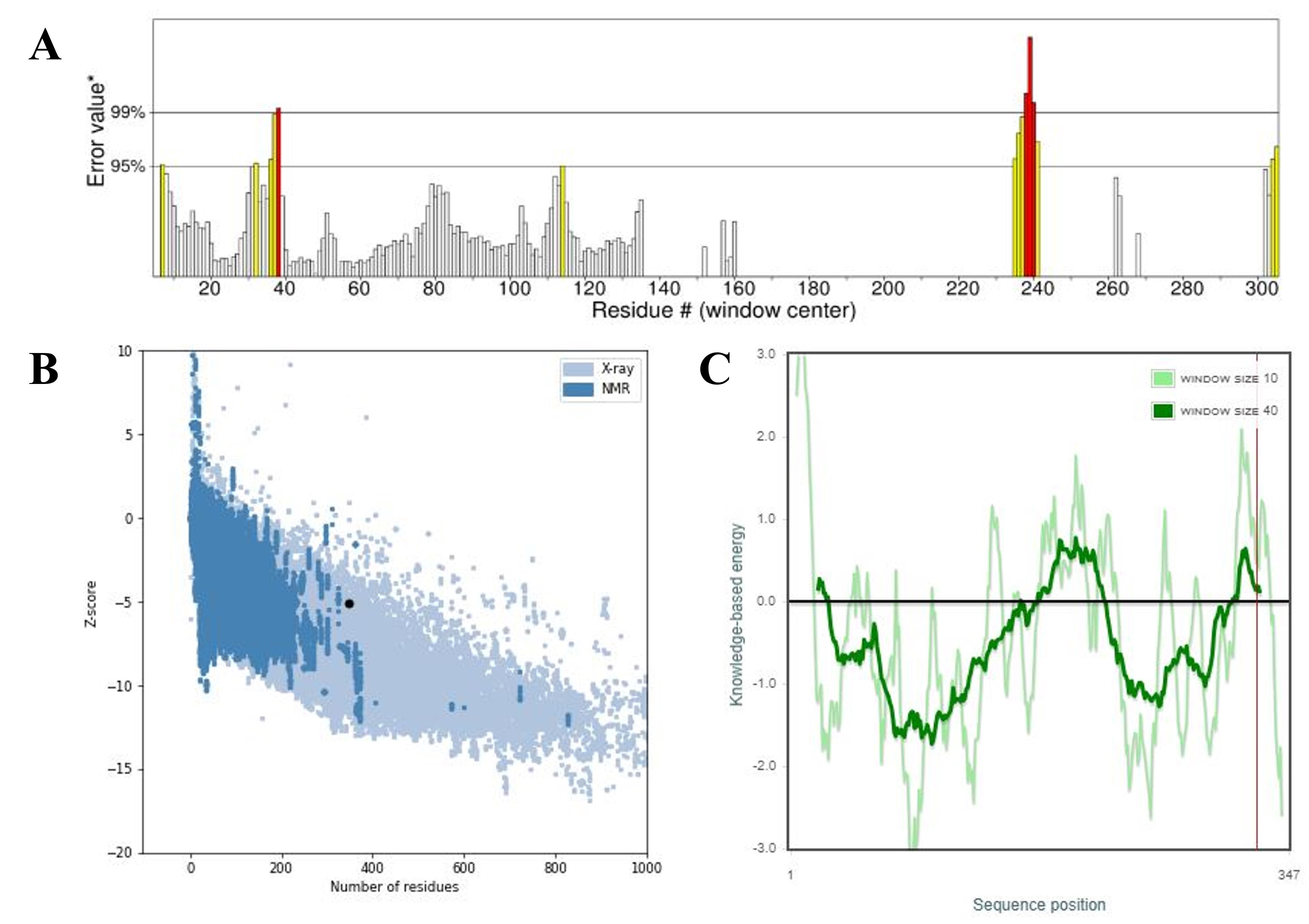

The 3D structure of the MEV construct was evaluated using AlphaFold2, one of the most advanced tools for protein structure modeling. To further improve the accuracy and quality of the model, structural refinement was performed using the GalaxyRefine server (Fig. 3B). Validation with a Ramachandran plot showed that 94.6% of the residues were in favored regions, 4.7% in allowed regions, and only 0.7% in outlier regions, indicating a reliable and well-refined structure. This suggests that most of the structure is relatively well-formed and strong (Fig. 3C). The calculated Z-score of –5.06 also proves the accuracy of the model. The quality check using ERRAT Saves 6.1 presented a high score of 89.873. Furthermore, the energy profile of the model indicated a constant energy, suggesting that the optimized structure is energetically stable and suitable for use in molecular modeling studies. Therefore, these results describe the excellent quality of the improved MEV structure (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Validation of the refined 3D structure of the MEV model. (A) The ERRAT score for the vaccine construct, (B) the Z-score of the improved model is –5.06, and (C) the refined structure local model quality. ERRAT, protein structure verification program. The asterisk (*) in Fig. 4A marks the overall quality factor (ERRAT score) of the modeled vaccine construct as calculated by the ERRAT server. It indicates the position of our model’s score on the quality scale, reflecting the percentage of residues with favorable non-bonded interactions. The black dot in Fig. 4B indicates the Z-score position of our modeled multi-epitope vaccine (MEV) structure on the ProSA-web validation plot. It shows the overall model quality in comparison with experimentally determined protein structures of similar size.

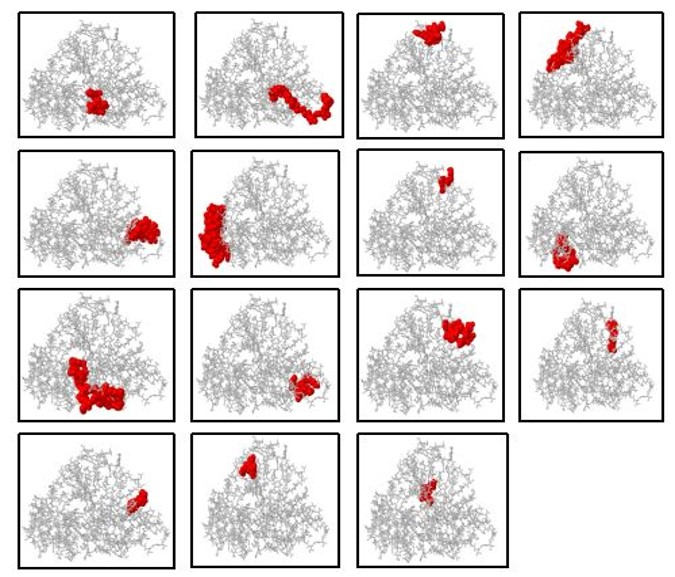

The ElliPro service was used to scan the tertiary structure of the vaccine and identify putative epitopes. The ElliPro service identified 12 linear and 15 conformational epitopes using the 3D structure of the MEV for the discontinuous B cell epitopes. The number of conformational epitopes ranged from 3 to 36 residues, and the associated pI scores ranged from 0.521 to 0.91, indicating the likelihood of antibody interaction. These results were graphically visualized using the PyMOL v.1.3 program to present the 3D structure of the conformational B cell epitopes. These anticipated epitopes are crucial in determining how the immune system detects and induces a strong immune response (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. Discontinuous B cell epitope of MEV. The MEV structure is shown in grey, while the conformational/discontinuous B cell epitopes are highlighted in red.

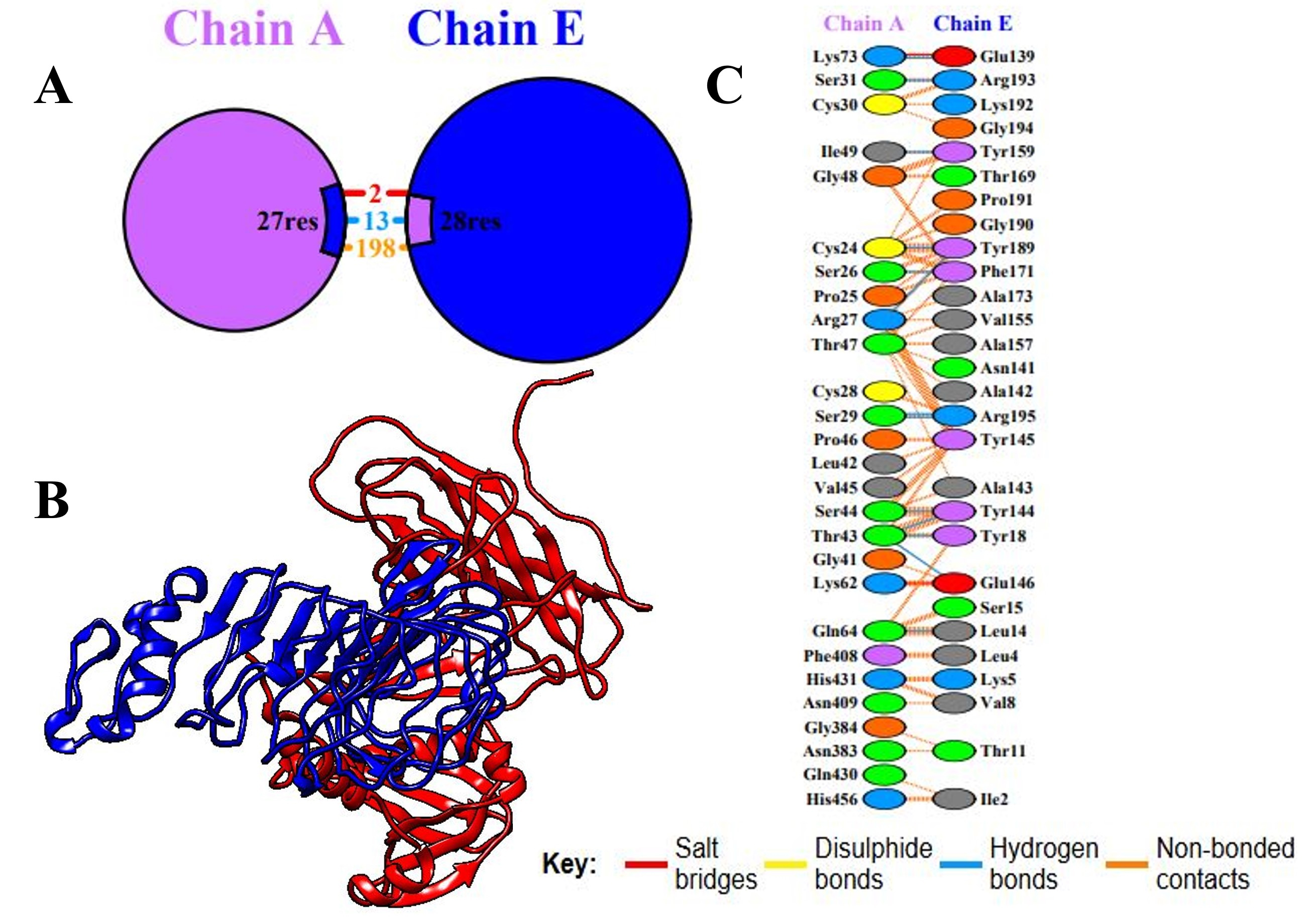

The interaction between the MEV construct and the TLR4 receptor (PDB ID: 2z66) was analyzed using the ClusPro 2.0 server. The best docking complex was selected based on the largest cluster size and the lowest interaction energy score, indicating a stable and favorable binding conformation. The selected MEV–TLR4 complex had an interaction energy score of –895.8, and the cluster size was 62, indicating a good binding affinity. Further scrutiny using PDBsum suggested that the MEV construct formed 13 hydrogen bonds with the receptor and had the highest contact number to chain D in TLR4. Thermodynamic parameters for the complex were calculated using the PRODIGY server, resulting in a Gibbs free energy of –17.4 kcal/mol and an equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd) of 1.7

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6. Molecular docking between TLR4 and the vaccination component. (A) Remaining residues that interact with the vaccine (chain E) and TLR4 (chain A). (B) The 3D interactions of the docked complex. (C) The key shows residue interactions across the interface of the bound molecules. TLR4, Toll-like receptor 4.

The iMODS server analyzed the docked MEV and the TLR4 receptor in terms of their protein flexibility and residue deformability. Regions that may easily change their conformational landscape are presented as peaks in the deformability graph. Deformability is the facility with which a protein can alter its 3D configuration. Comparing the NMA and PDB data, a significant B-factor graph was drawn, indicating that the NMA predicted higher B-factors than those found in the PDB data; thus, a computationally predicted model contains more mobility and flexibility than the experimentally observed structure. Further confirmation of the flexibility and stability of the protein complex was obtained through eigenvalue analysis in the graph, which shows that lower values indicate a lower energy requirement to deform the structure. The graph of variance, showing cumulative variance in green and individual variance in red, proved inversely related to the eigenvalue graph. Further, the relationship between residues is demonstrated through the covariance matrix, which employs red to denote correlated interactions, white to denote uncorrelated interactions, and blue to denote anti-correlated residues. This analysis strengthened the reliability of the predicted model by showing an improved correlation between residue pairs in the docked complex, which further contributed to the stability and flexibility of the MEV–TLR4 interaction (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7. The molecular dynamics (MD) of the vaccine protein complex. (A) The stability of the vaccine was assessed using low main-chain deformability. (B) The B factor, or mobility. (C) Covariance matrix. (D) The residues are shown in a stiffer state in the elastic network model. (E) The eigenvalue presents the stiffness of the motion and the normal mode of the protein.

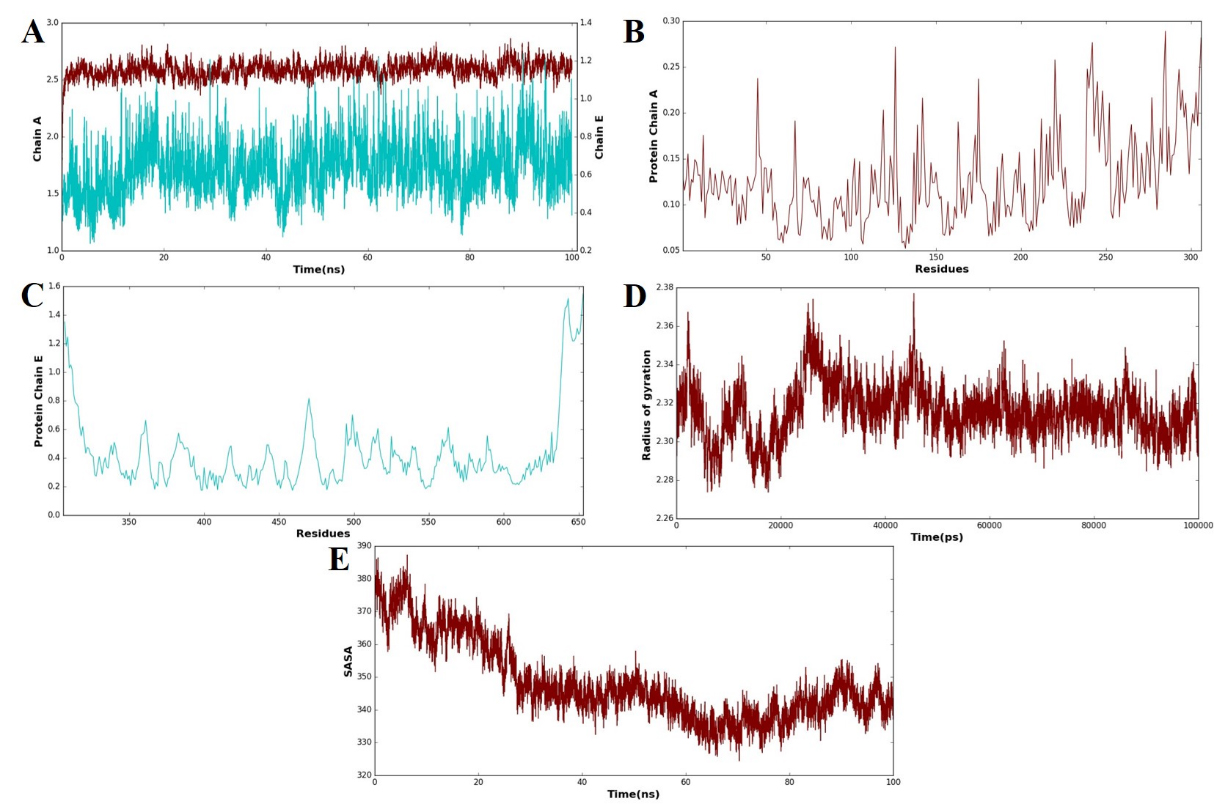

MD simulations were conducted using the GROMACS 2025 package to assess the stability and conformational dynamics of the vaccine construct (chain E) in complex with the receptor (chain A). The simulation pathway was inspected using essential structural measures, such as root mean square deviation (RMSD), root mean square fluctuation (RMSF), radius of gyration (Rg), and solvent-accessible surface area (SASA). These parameters provided extensive information on the conformational stability, mobility, compactness, and interaction profile of the vaccine–receptor complex. As evidenced in Fig. 8A, the RMSD analysis of chain A and chain E revealed stable behavior during the course of the 100 ns simulation. Chain A had comparatively smaller deviations than chain E, in accordance with its structural stiffness, while the greater fluctuations of chain E indicate the dynamic flexibility of the vaccine complex. Regardless of these oscillations, the traces stayed within a tolerable range, indicating general stability of the complex. The RMSF profile presented in Fig. 8B (chain A) and Fig. 8C (chain E) demonstrated residue-level flexibility. In chain A, the majority of the residues showed negligible fluctuations, validating the structural stability of the receptor. Conversely, Chain E exhibited significant fluctuations at some positions, which could be ascribed to the inherent flexibility of the vaccine construct design. These flexible areas are likely to allow molecular recognition and binding with the receptor, potentially maximizing binding flexibility. The Rg plot (Fig. 8D) indicated uniform values with slight fluctuations, inferring that the complex was a compact architecture throughout the simulation. This compactness agrees with the idea of a stable structural organization in the vaccine–receptor complex. The SASA analysis (Fig. 8E) revealed a decrease in solvent-exposed surface area over time, which implies an evolution toward a more compact and tightly bound structure. The decrease observed in the SASA analysis closely relates to improved intermolecular contacts, supporting the stability and favorable interaction of the vaccine construct with the receptor. Overall, these data authenticate that the vaccine construct formed a stable and compact complex with the receptor, with flexibility being mostly localized within the vaccine chain. Such dynamic flexibility, along with diminished solvent exposure and constant compactness, emphasizes the strength of the interaction between the vaccine candidate and the receptor protein.

Fig. 8.

Fig. 8. MD simulation analysis of the vaccine–receptor complex. (A) Root mean square deviation (RMSD) plots of chain A (receptor) and chain E (vaccine construct) over a 100 ns simulation that reflects the overall structural stability. (B) Root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) profile of receptor residues with restricted flexibility along the trajectory. (C) RMSF profile of vaccine construct residues that show the localized areas of high flexibility. (D) A plot of the radius of gyration (Rg) illustrates the compactness of the vaccine–receptor complex throughout the simulation. (E) Solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) plot that presents a steady decrease in solvent exposure, which is indicative of increased compactness and stable binding of the complex. The blue line represents the receptor (chain A), while the brown line represents the vaccine construct (chain E). These color codes are consistently used across all panels (A–E) to differentiate between the two components during molecular dynamics (MD) simulation analyses, including RMSD, RMSF, Rg, and SASA plots.

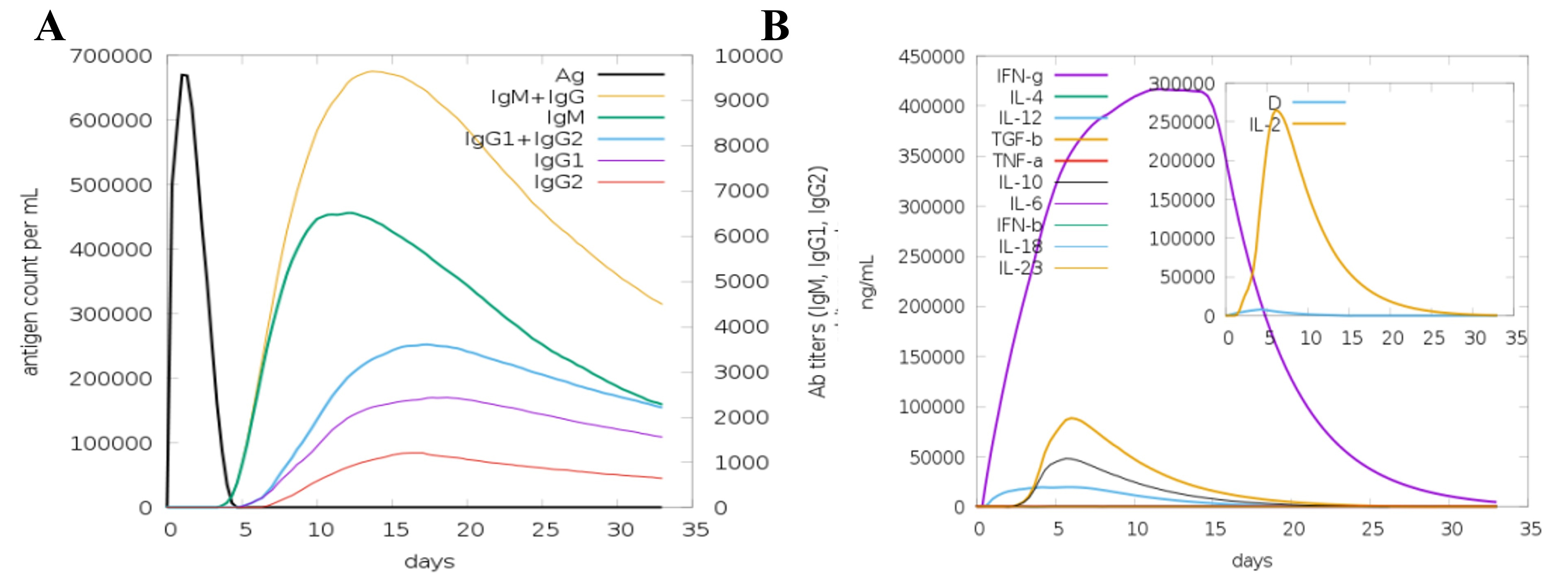

Immunity to a disease is founded on both primary and secondary immune responses. The key immune response is characterized by the first peak of IgG and IgM antibodies, which are crucial for finding and clearing infections. The secondary immune response is induced when the immune system encounters the pathogen again. In this response, IgM, IgG1, IgG2, and IgG3 antibodies are synthesized more rapidly and intensively. Hence, the antigen is reduced more quickly and efficiently. Coordination and facilitation of the immune response, involving cytokine and interleukin responses, are essential for immune system cells to communicate and attack the pathogen. According to reports, the disease was eradicated powerfully after successive exposures following immunization, thereby showing the ability of the immune system to produce long-lasting protection. These results demonstrate the capacity of the immune system to establish a powerful, flexible, and receptive defense mechanism necessary for designing vaccines and treatments that efficiently repel the disease (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

Fig. 9. In silico immune simulation of the humoral and cellular immune responses to the MEV. A simulated immune response in which the MEV acts as an antigen (A), the generation of immunoglobulins and B cell isotypes in response to antigen exposure; (B) the production of cytokines and interleukins at different stages using the Simson index.

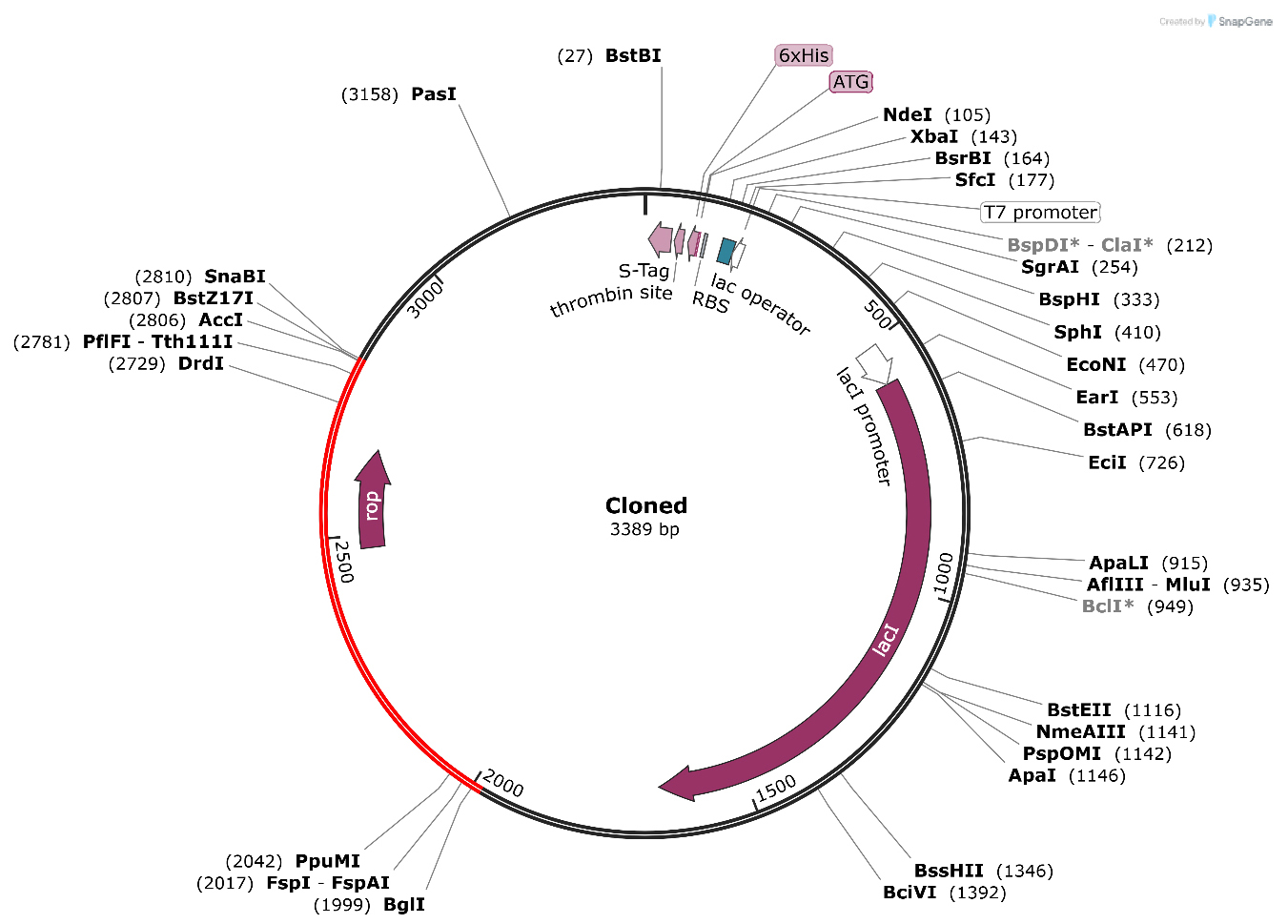

Codon optimization is a vital approach to enhancing translational efficiency, particularly for the foreign gene in E. coli. Species-specific patterns of codons may impede efficient translation of the target gene. The JCat method, specifically designed for the E. coli K12 strain, was used to optimize the codon usage of the produced vaccine for our purposes. The optimization conditions of a GC content of 51.6% and a CAI of 0.9 reveal that the sequence is very suitable for strong expression in the E. coli system. Then, the optimized codon sequence was placed between the proper restriction sites and Nco1 in the expression vector pET30a(+). The final recombinant plasmid contained the protein sequence of the vaccine and had a total size of 3389 base pairs; therefore, the arrangement would efficiently produce the vaccine protein in E. coli and pave the pathway for additional verification and use in the development of vaccines (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10.

Fig. 10. The in silico cloning of the vaccine into the E. coli K12 host expression system. The plasmid is displayed in black, while the inserted nucleotide sequence is shown in red. The grey font represents the vector backbone sequences of the pET28a(+) plasmid, indicating regions that were not modified during cloning. The asterisks (*) mark the restriction enzyme recognition sites (EcoRI and HindIII) used for inserting the designed vaccine gene into the plasmid vector.

Vaccination is an important strategy to combat pathogens [68, 69]. However, vaccine development using traditional approaches is expensive and laborious [70, 71]. The latest developments in computational tools and software have created a broad spectrum for developing protection against human pathogens [70]. Therefore, in silico-based approaches are used efficiently to overcome these drawbacks of conventional vaccine development. A. urinae, a facultative anaerobe, is part of the urinary tract microbiota but has been implicated in UTIs, particularly in older individuals and those with pre-existing conditions [1]. Since A. urinae can lead to invasive diseases such as sepsis and endocarditis, there is an urgent need for vaccines [2].

In this research, an immunoinformatics and subtractive proteomics pipeline was used to identify essential, non-toxic, non-homologous, and antigenic proteins for vaccine development [19]. A total of 1684 proteins from A. urinae were analyzed using the Geptop 2.0 server, which identified 283 proteins as essential. Essential proteins emerged as the best target for developing subunit vaccines [57, 72]. These proteins can have similar domains to human proteins, which means these proteins can interfere with human metabolism and might be lethal. Therefore, all proteins with significant similarity to the human proteome were removed through BlastP, and 127 non-homologous proteins were selected for further analysis. In fact, two outer membrane proteins (a single-stranded DNA-binding protein and a cell division protein, FtsZ) were selected based on the associated immunogenic properties. In bacteria, single-stranded DNA-binding proteins consist of an N-terminal domain that is highly conserved and responsible for DNA binding and tetramerization, and a less conserved C-terminal domain that interacts with other proteins [73]. These proteins have essential protective roles in genome biology and Shield single-stranded DNA from damage [74]. Similarly, FtsZ is a conserved protein and plays a vital role during the cell division process of bacteria. FtsZ is mainly used to create a scaffold, the Z-ring, for recruiting other proteins that participate in the process of cell division [75]. FtsZ has also proved a promising target for creating subunit and DNA vaccine candidates against S. suis infection [76]. FtsZ has also been demonstrated to be a promising vaccine antigen against Pseudomonas aeruginosa [77].

A comprehensive antigenicity and allergenicity evaluation ensured that these proteins were suitable for inclusion in the MEV construct, eliminating the risks of an autoimmune reaction [13]. The epitope selection process emphasized generating a strong immune response by including highly antigenic B and T cell epitopes, which were further validated by population coverage analysis predicting 79% global applicability [21]. The design of the MEV construct was carefully optimized by employing peptide linkers such as GPGPG, AAY, and KK to enhance structural integrity and immunogenic potential [62]. The inclusion of the CTB as an adjuvant aimed to amplify the immune response while maintaining safety [29]. Evaluation of the physicochemical properties confirmed the stability, antigenicity, and non-allergenicity of the vaccine, as the vaccine has no homology to human proteins, thereby reducing the risk of cross-reactivity [78]. The secondary and tertiary structure predictions further confirmed that the construct was stable and functional, with very high scores in the Ramachandran plot analysis and other validation metrics [79].

The stability interactions were between the MEV construct and immune receptors, particularly TLR4 [80]. This evidence indicates the potential of the vaccine to be highly effective in initiating innate pathways, which are significant for the adaptive response [8]. The immune simulation studies also showed that the vaccine can elicit primary and secondary immune responses, indicating that the vaccine should induce long-term immunity [81].

In silico cloning ensured the efficiency of the vaccine by optimizing parameters such as the GC content and CAI for high translational efficiency [82]. The results collectively underpin the viability of this MEV construct as a candidate for further experimental validation and eventual clinical application [13].

The development of this MEV against A. urinae is a critical advancement toward new therapeutic approaches, especially in the face of the rising challenge of antibiotic resistance and the emergence of new pathogens. Further in vitro and in vivo validation of these computational results should be conducted to prove the safety and efficacy of the vaccine [83]. More work is required to address any potential shortcomings and further optimize the construct, although these findings are promising.

This study employed a reverse vaccinology approach to analyze the genome of Aerococcus urinae strain CCUG 59500, leading to the identification of two conserved antigenic proteins. A novel MEV candidate was designed by selecting high-ranking epitopes from both antigens using advanced immunoinformatics tools. The construct was further evaluated through MD simulations and protein–protein docking analyses. The application of computational methods greatly accelerated the vaccine discovery process, reducing both time and cost. The designed vaccine demonstrates favorable physicochemical, structural, and immunological properties, highlighting the potential of the vaccine to induce strong humoral and cellular immune responses against A. urinae. Moreover, the vaccine is predicted to be efficiently overexpressed in the Escherichia coli strain K12. Nonetheless, experimental validation is essential to confirm the efficacy and safety of this promising vaccine candidate.

AAY, alanine–alanine–tyrosine; AI, artificial intelligence; BLAST, basic local alignment search tool; BMC, BioMed Central; CAI, codon adaptation index; CCUG, Culture Collection, University of Gothenburg; CELLO, subCELlular LOcalization predictor; COV/COVID, coronavirus disease; CTB, cholera toxin subunit B; CTL, cytotoxic T lymphocyte; DRB1, human leukocyte antigen-DR beta 1; EAAAK, glutamic acid–alanine–alanine–alanine–lysine; ERRAT, protein structure verification program; FASTA, text-based format for nucleotide/amino acid sequences; FEBS, Federation of European Biochemical Societies; FFT, fast Fourier transform; GPGPG, glycine–proline–glycine–proline–glycine; GROMACS, Groningen Machine for Chemical Simulations; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; HPIV, human parainfluenza virus; HTL, helper T lymphocyte; IEDB, Immune Epitope Database; JCM, Journal of Clinical Microbiology; JOSS, Journal of Open Source Software; LBL, linear B-cell lymphocyte epitope; LINCS, linear constraint solver (molecular dynamics); LOS, lipooligosaccharide; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; MD, molecular dynamics; MEBV, multi-epitope-based vaccine; MEV, multi-epitope vaccine; MFPPI, multi-FASTA ProtParam interface; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; NCBI, National Center for Biotechnology Information; NMA, normal mode analysis; NPT, constant number of particles, pressure, temperature (ensemble); NVT, constant number of particles, volume, temperature (ensemble); PDB, Protein Data Bank; PRODIGY, protein binding energy prediction server; RAMPAGE, Ramachandran plot assessment tool; RMSD, root mean square deviation; RMSF, root mean square fluctuation; SASA, solvent-accessible surface area; SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome; SOPMA, Self-Optimized Prediction Method with Alignment; TIGR4, Streptococcus pneumoniae TIGR4 strain; TLR4, Toll-like receptor 4.

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. Additional datasets are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

FA was responsible for the conception o ideas presented, writing, and the entire preparation of this manuscript.

According to Saudi Arabian regulations and institutional policies, this study does not involve human or animal subjects. The work was based solely on computational analyses involving microbial genome data available in public databases; therefore, ethical committee approval was not required.

The author would like to thank the Deanship of Scientific Research from Shaqra University for support and encouragement of the researchers.

This research received no external funding.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

During the preparation of this work, the author used ChatGPT to check spelling and grammar. After using this tool, the author reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.