1 Department of Interventional Therapy, Tianjin Medical University Institute and Hospital, National Clinical Research Center for Cancer, 300000 Tianjin, China

2 Tianjin’s Clinical Research Center for Cancer, Tianjin Medical University Institute and Hospital, 300000 Tianjin, China

3 Key Laboratory of Cancer Prevention and Therapy, Tianjin Medical University Institute and Hospital, 300000 Tianjin, China

4 Department of Oncology, Tianjin Beichen Hospital, 300400 Tianjin, China

Abstract

Topotecan (TPT) is a novel class of anti-tumor drugs known for its broad-spectrum anti-cancer activity and low toxicity. This study aimed to investigate the potential mechanisms through which TPT mediates the phosphatase and tensin homolog/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/glycogen synthase kinase-3β (PTEN/PI3K/GSH-3β) signaling pathway to affect survival and tumor growth in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) xenograft nude mice.

A NSCLC nude mouse model was fabricated by subcutaneously injecting H1993 human NSCLC cells into the right axillary fossa. The mice were treated with cisplatin (DDP) and 0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 mg/kg of TPT. Tumor volume changes were monitored and assessments were performed on organ indices, immune function, tumor cell apoptosis, survival rates (SRs) and protein levels of components involved in the PTEN/PI3K/GSK-3β pathway in tumor tissues. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or Chi-square tests were conducted using SPSS 23.0 to compare intergroup differences.

The SRs of nude mice treated with DDP and TPT markedly increased, with high-dose TPT treatment showing a drastically superior SR to DDP (p < 0.05). As the dose of TPT increased, the tumor volumes in the mice decreased markedly, and the indices of the thymus and spleen notably increased. Among T lymphocyte subsets, the proportion of CD4+ cells and the CD4+/CD8+ ratio increased, while the proportion of CD8+ cells decreased. Serum levels of interleukin-4, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and interferon-γ increased. The apoptosis rate of tumor cells increased, and the relative expression level of PTEN in tumor tissue increased, whereas the levels of p-PI3K, p-PI3K/PI3K ratio, p-GSK-3β, and p-GSK-3β/GSK-3 ratio decreased (p < 0.05).

TPT dose-dependently inhibited NSCLC growth by modulating T-cell subsets, enhancing immune function, and exerting antitumor effects through the PTEN/PI3K/GSK-3β pathway. The high-dose group (2.0 mg/kg) demonstrated superior efficacy compared to the cisplatin and low-dose groups, validating the importance of concentration gradient design in determining the optimal therapeutic window.

Keywords

- Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

- Topotecan

- T lymphocyte subsets

- immune function

- PTEN/PI3K/GSK-3β pathway

Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) constitutes over 85% of lung cancer (LC) cases [1]. Most NSCLC patients present with advanced disease at diagnosis, leading to a high incidence of distant metastasis post-curative surgery and poor prognosis. Advances in chemotherapy and the application of targeted therapies have markedly improved response rates and 5 years survival rates (SRs) for NSCLC. However, factors such as treatment resistance pose limitations to further research in various targeted therapies [2, 3].

The Topotecan (TPT) is derived from camptothecin and inhibits DNA topoisomerase I. It binds with both the enzyme and DNA, blocking the repair of single-strand DNA breaks [4]. DNA topoisomerase I is a crucial enzyme involved in DNA replication and repair, responsible for unwinding DNA and inducing single-strand breaks while forming a single-strand DNA sheath between DNA strands. As a DNA topoisomerase I inhibitor, TPT binds to the enzyme and disrupts DNA replication and repair processes, preventing cancer cells from continuing to grow and divide [5]. In addition to direct inhibition of DNA topoisomerase I, TPT also induces DNA breaks, further exacerbating damage to cancer cells [6]. Moreover, TPT induces cell apoptosis (programmed cell death) and arrests cells from progressing from the G2 phase to the M phase (mitosis), thereby further suppressing tumor cell proliferation [7]. The TPT is primarily used clinically to treat diseases such as SCLC and metastatic ovarian cancer. As a chemotherapy agent, TPT demonstrates significant efficacy and can synergize with taxanes or platinum-based drugs to enhance anticancer activity. Takahashi et al. [8] confirmed in clinical treatment of SCLC patients that employing TPT alone or in combination with Berzosertib suggested negligible differences in progression-free survival and adverse reactions, but combination therapy notably extended overall survival. Edelman et al. [9], discovered that combining TPT with Irinotecan drastically extended SR in patients with recurrent/refractory SCLC. Baize et al. [10], also found that combining TPT with cisplatin chemotherapy increased SR in SCLC patients. Common severe adverse effects include neutropenia, thrombocytopenia and anemia. Currently, TPT is approved for NSCLC. Nevertheless, more research is needed to explore the efficacy and mechanisms of TPT in treating NSCLC.

This work established an NSCLC nude mouse model by subcutaneously injecting H1993 human NSCLC cells into the right axillary fossa. Effects of cisplatin (DDP) and different concentrations of TPT on SRs, immune function, tumor growth and tumor cell apoptosis in the nude mouse model were compared. The goal was to provide reference data for investigating the potential mechanisms of TPT in treating NSCLC.

The research was performed at Tianjin Medical University Institute and Hospital (Tianjin, China) from January, 2023 to January, 2024.

Human NSCLC cell line H1993 (obtained from ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) was cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) (+10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA)). The cell line was validated by STR profiling and tested negative for mycoplasma. Cultures were maintained in a humidified atmosphere at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Cells were used for experiments upon reaching the logarithmic growth phase, adjusted to 1

A total of 100 clean-grade male BALB/c-Nu nude mice (Jiangsu Wukong Biotechnology Co. Ltd., Nanjing, China), weighing 18–20 g and aged 4–6 weeks, were selected for the study. The mice were kept in an animal facility at temperatures of 22–25 °C and a relative humidity of 55%. Mice had unrestricted access to food and water and were under a 12/12 hrs light/dark cycle, with 5 mice housed per cage.

The experimental protocol was approved by the Animal Ethical Committee of Tianjin Medical University Institute and Hospital (No. WDRY2022-K032). All the experimental protocols involved in the current investigation followed the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health and the ARRIVE (Animal Research: Reporting of in vivo experiments) guidelines.

The nude mice were randomly rolled into Ctrl group (CG), DDP group (DG), 0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 mg/kg TPT group (TG), with 20 mice per group. All mice were subcutaneously inoculated with 0.2 mL of H1993 cell suspension in the right axilla. When the tumor volume reached approximately 0.1 cm3, the DG received intraperitoneal injections of 2 mg/kg DDP (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in 0.4 mL, twice per week for a total of 6 injections. The 0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 mg/kg TGs were orally gavaged with different concentrations of TPT daily for 30 consecutive days.

After gastric gavage treatment, tumor volume was measured utilizing a caliper every five days and SRs of mice were recorded. At the treatment period end, surviving nude mice were anesthetized intraperitoneally with 40 mg/kg of 2% sodium pentobarbital (produced by Foshan Chemical Experiment Factory, Foshan, China) and euthanized by cervical dislocation under aseptic conditions. Tumors, spleens and thymi were harvested, washed with phosphate-buffered saline and prepared for further analysis. The spleen index and thymus index were calculated accordingly.

Before euthanizing of mice, 4 mL of venous blood was collected and treated with sodium heparin as an anticoagulant. Serum was then processed for the detection of Interleukin (IL)-4, Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF)-

Venous blood was collected and anticoagulated, followed by serum separation. Mouse anti-CD4 antibody (BioLegend, Cat# 100510, clone RM4-5) and mouse anti-CD8 antibody (BioLegend, Cat# 100708, clone 53-6.7) were separately added and incubated in the dark for 15 min. Subsequently, 250 µL of sterile water was added and CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocyte subsets in peripheral blood were measured utilizing a CytoFLEX flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). The CD4+/CD8+ ratio was calculated accordingly.

One-third of the tumor tissue was taken and minced with ophthalmic scissors and centrifugated at 1000 rpm for 5 min. Applying Annexin V FITC/PI apoptosis detection kit (Beijing AnnuoRun Biological Technology Co. Ltd., Beijing, China), cells were resuspended in pre-cooled binding buffer, then incubated in the dark at room temperature for 10 min with 5 µL each of Annexin V-FITC and PI working solution added. The apoptosis rate of tumor cells was measured utilizing a CytoFLEX flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA).

The frozen tumor tissue was pulverized in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was extracted employing radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) and RNA concentration was quantified with a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). Thirty micrograms of protein were loaded onto SDS-PAGE gels, separated and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes blocked with 5% non-fat milk, then probed overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies (Abcam, Shanghai, China) against chromosome ten, Phosphatase and Tensin Homolog (PTEN) (ab32199), Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) (ab40755), p-PI3K (ab182651), glycogen synthase kinase-3

Data analysis utilized SPSS 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous variables were expressed as mean

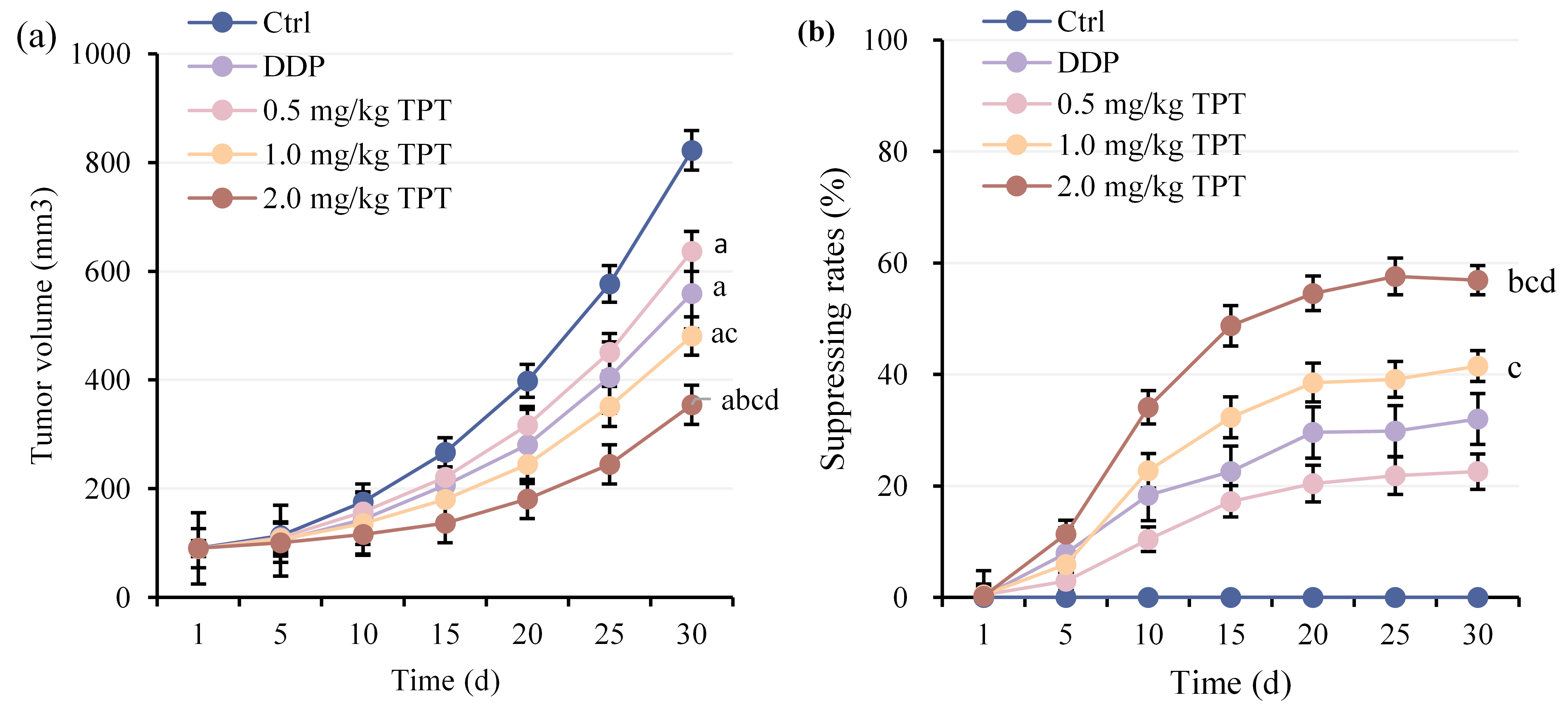

A comparison of tumor volume changes in nude mice with NSCLC xenografts was conducted (Fig. 1a). As time progressed, tumor volumes increased in all groups. Tumor volumes greatly decreased in DG, 0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 mg/kg TG versus CG (p

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Comparison of tumor volumes among groups of nude mice. (a) Tumor volume changes and (b) Tumor volume inhibition rate changes. ap

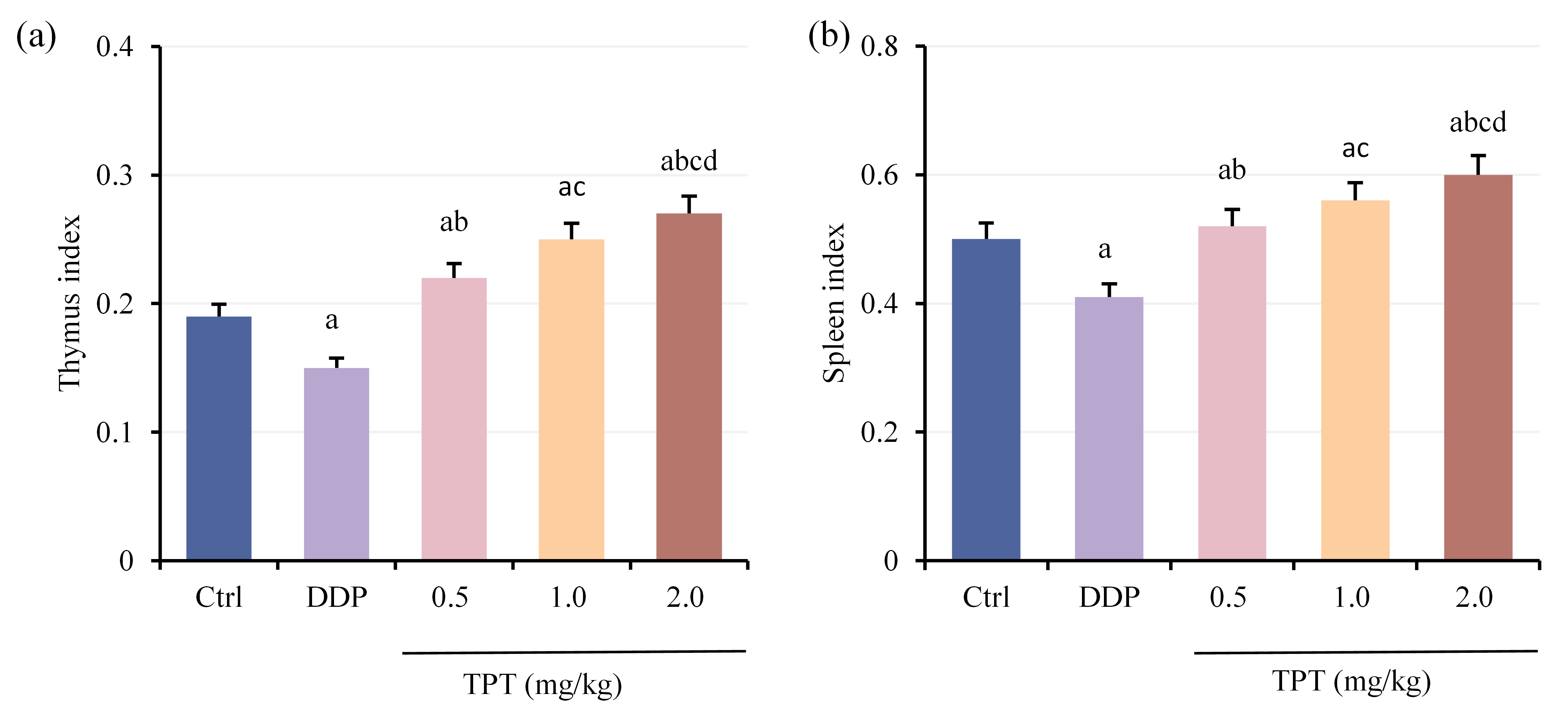

Comparison of thymus index (Fig. 2a) and spleen index (Fig. 2b) among different groups of nude mice with NSCLC xenografts showed that DG suggested prominent decreases in both thymus and spleen indices versus CG. At the same time, 1.0 and 2.0 mg/kg TG exhibited drastic increases (p

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Comparison of organ indices among groups of nude mice. (a) Thymus index and (b) Spleen index. ap

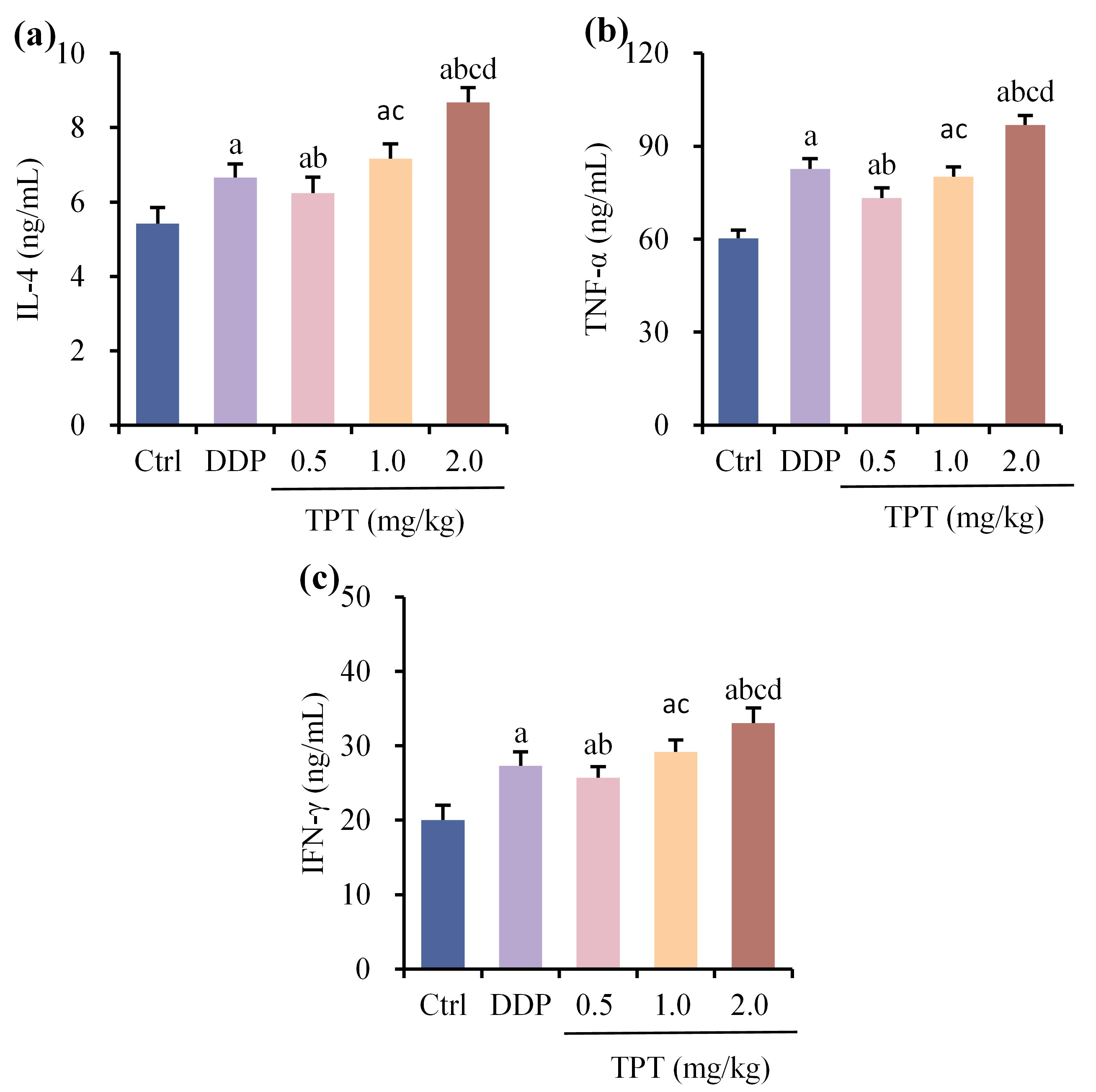

Comparison of serum interleukin (IL)-4 (Fig. 3a), tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Comparison of serum interleukin (IL)-4, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-

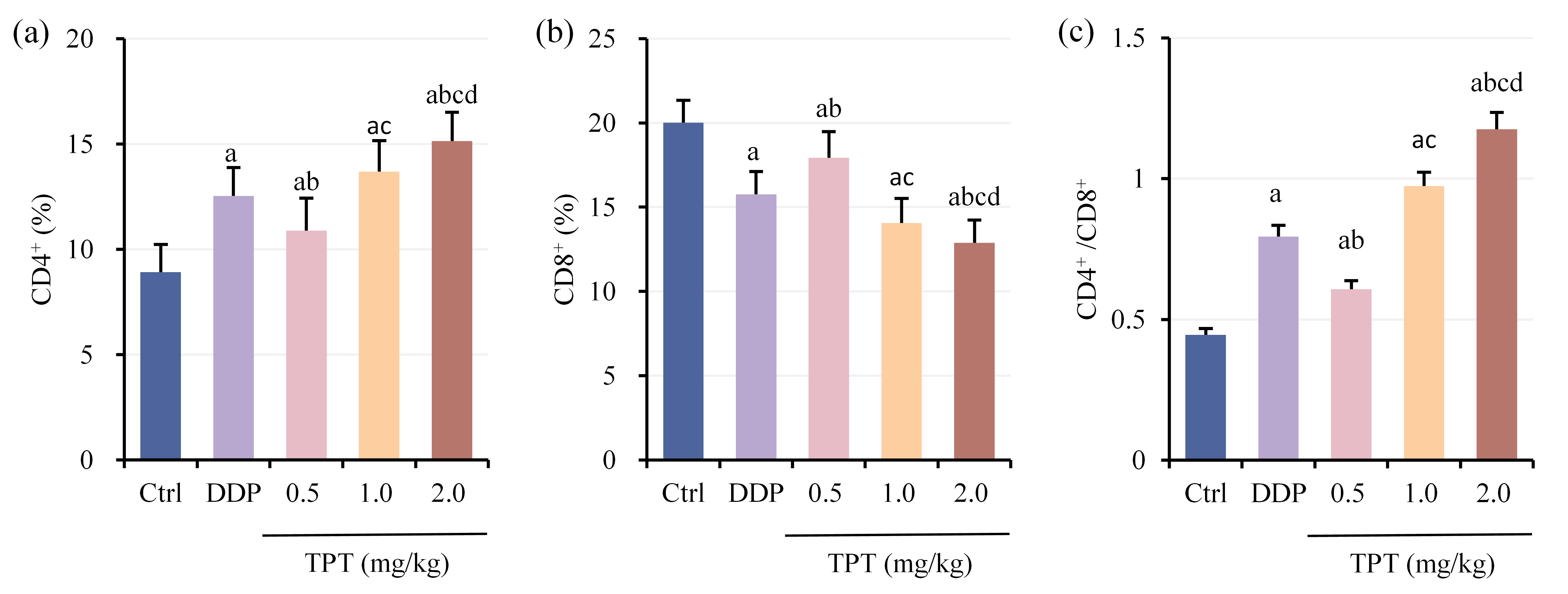

Serum CD4+ ratio (Fig. 4a), CD8+ ratio (Fig. 4b) and CD4+/CD8+ ratio (Fig. 4c) were compared among different groups of nude mice with NSCLC xenografts. Relative to CG, all other groups suggested drastic increases in CD4+ ratio and CD4+/CD8+ ratio, while CD8+ ratio was greatly decreased (p

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Comparison of T lymphocyte subset levels among groups of nude mice. (a) CD4+ cell proportion, (b) CD8+ cell proportion and (c) CD4+/CD8+ ratio. ap

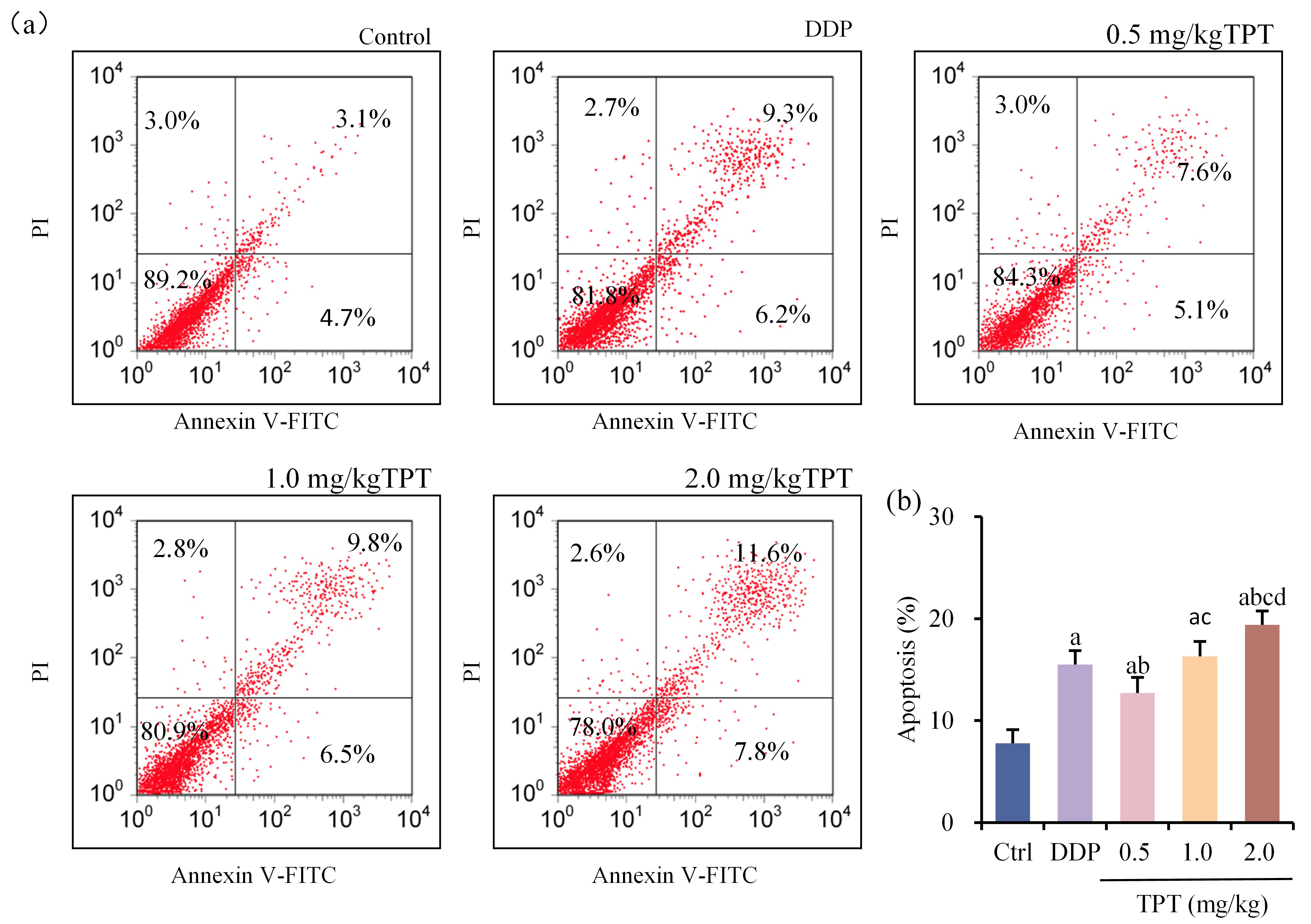

Comparison of tumor cell apoptosis rates among different groups of nude mice with NSCLC xenografts was shown in Fig. 5a,b. Tumor cell apoptosis rates were markedly increased in all groups except CG (p

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. Comparison of tumor cell apoptosis rates among groups of nude mice. (a) Flow cytometry plots for apoptosis detection and (b) Comparison of tumor cell apoptosis rates. ap

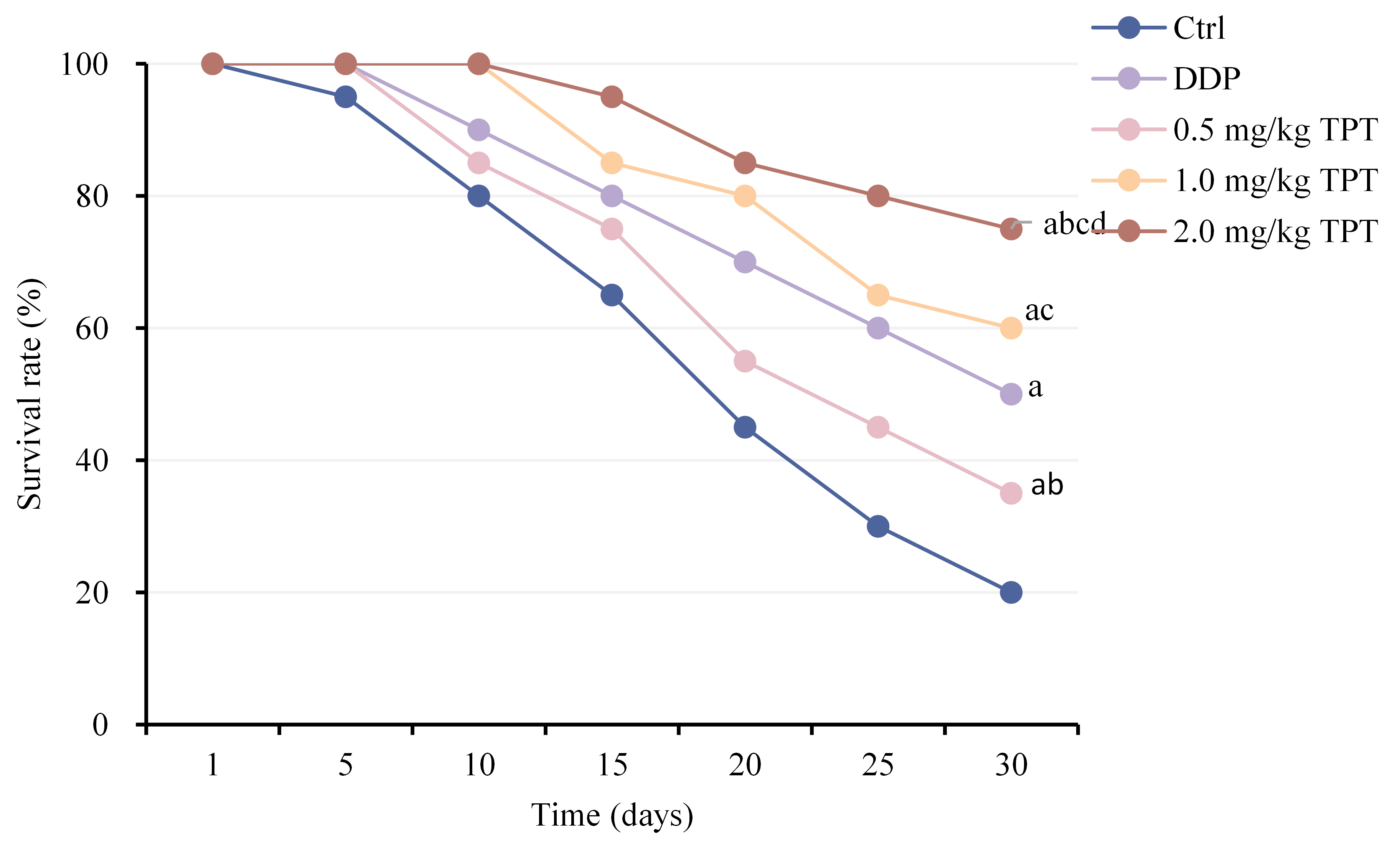

Comparison of SRs among different groups of nude mice with NSCLC xenografts (Fig. 6) showed that SRs were markedly increased in all groups except CG (p

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6. Comparison of survival rates (SRs) among groups of nude mice.ap

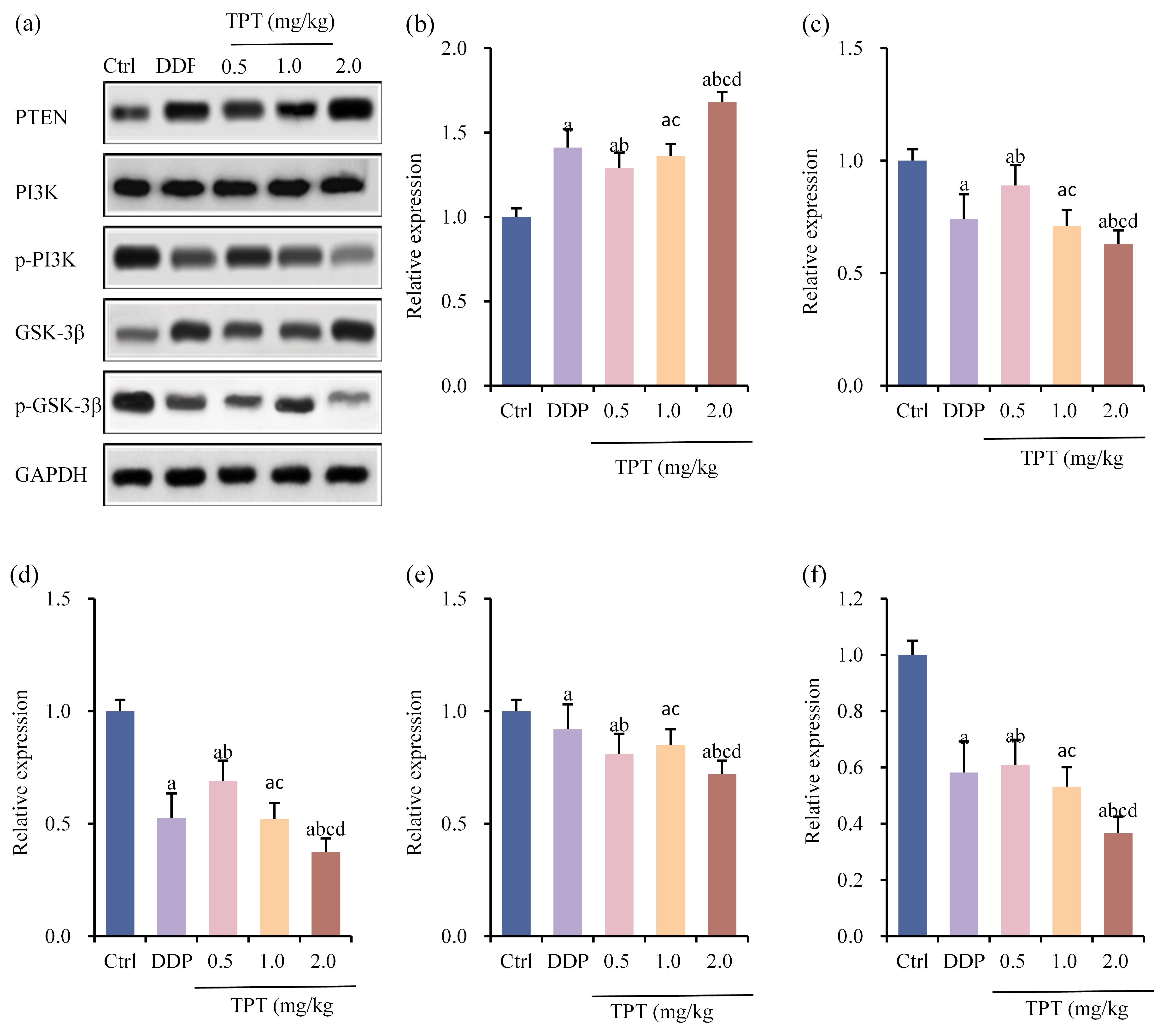

The relative expression levels of phosphatase and tensin homolog/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/glycogen synthase kinase-3

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7. Comparison of tumor PTEN/PI3K/GSK-3

The TPT was observed to drastically enhance SRs and suppress tumor volume growth in nude mice carrying NSCLC tumors, showing a dose-dependent response. The NSCLC arises from the bronchial mucosal epithelium. Most patients have grim prognosis and numerous complications [11]. The DDP is standard first-line therapy for advanced NSCLC, often combined with radiotherapy to benefit patients drastically [12, 13]. Nevertheless, resistance to treatment can develop in some patients during therapy, which compromises its effectiveness. The mechanism of action of TPT in cancer treatment primarily involves inhibiting the activity of DNA topoisomerase I, thereby disrupting DNA replication and repair processes and inducing DNA breakage and cell apoptosis [14]. Zhang et al. [15], found that folate-conjugated TPT liposomes effectively reduced tumor volume and prolonged circulation time in rats bearing A549 LC xenografts. However, the precise mechanism by which TPT treats NSCLC requires further exploration.

The thymus and spleen are crucial immune organs, integral to both central and peripheral immune systems [16]. It was observed that after treatment with DDP, the thymus and spleen indices decreased in nude mice bearing NSCLC tumors, indicating immune suppression in the host organism. Conversely, following administration of TPT, an increase in thymus and spleen indices was noted, showing a dose-dependent effect. This suggests that TPT can enhance thymus and spleen indices in nude mice bearing NSCLC tumors, thereby boosting both humoral and cellular immune functions. During the growth of LC cells, drastic immune evasion mechanisms exist, which are crucial factors in inducing LC development [17]. Changes in T lymphocyte subset levels can directly reflect the body’s ability to inhibit tumor growth, including the major subsets CD4+ and CD8+ [18, 19, 20]. The CD4+ T cells facilitate immune cell proliferation and differentiation and coordinate interactions among immune cells [21]. As key effector cells in anti-tumor immunity, CD8+ cells typically inhibit tumor growth by directly killing tumor cells and secreting cytokines [22]. Conversely, an imbalance in the CD4+/CD8+ T-cell subset ratio or functional exhaustion of CD8+ T cells may impair antitumor immunity, thereby facilitating tumor immune escape. It has been observed that after treatment with DDP and TPT, the peripheral blood CD4+ cells and CD4+/CD8+ ratio markedly increased in nude mice bearing NSCLC tumors, while the proportion of CD8+ cells decreased markedly. Particularly, treatment with high doses of TPT led to more pronounced changes in T lymphocyte subset levels. This suggests that TPT can correct abnormal T lymphocyte subset levels in the body, improve immune suppression and thereby drastically enhance immune function in nude mice bearing NSCLC tumors.

The IL-4 is an anti-inflammatory cytokine secreted by Th2 cells that promotes differentiation of Th0 cells into Th2 cells [23]. The TNF-

During tumor initiation and progression, dysregulated tumor suppressor gene phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on PTEN can disrupt its normal control over the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/AKT) pathway. This disruption leads to unchecked cell proliferation, contributing to the development of cancer [29]. Abnormal PI3K/AKT pathway activation promotes the proliferation, migration and invasion of LC cells, facilitating disease progression [30]. Glycogen synthase kinase-3

The TPT, as a topoisomerase I inhibitor, holds significant importance in the study of NSCLC. This research demonstrates that TPT can correct the imbalance of T lymphocyte subsets by mediating the PTEN/PI3K/GSK-3

The TPT demonstrated dose-dependent characteristics in enhancing SRs and inhibiting tumor growth in nude mice with NSCLC xenografts. Its mechanism of action involves inducing tumor cell apoptosis, correcting imbalances in T lymphocyte subsets in nude mice, enhancing immune function and influencing the expression of PTEN, PI3K and GSK-3

This study investigated the efficacy of Topotecan in the treatment of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) via the PTEN/PI3K/GSK-3

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

CT and HPY designed the research study. CT and HPY performed the research. CT, ML and WL analyzed the data. CT and HPY drafted and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The experimental protocol was approved by the Animal Ethical Committee of Tianjin Medical University Institute and Hospital (No. WDRY2022-K032). All the experimental protocols involved in the current investigation followed the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health and the ARRIVE (Animal Research: Reporting of in vivo experiments) guidelines.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.