1 Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 56000 Cheras, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

2 Faculty of Pharmacy, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 50300 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Abstract

Oxidative stress and inflammation are widely recognized as key mechanisms in the pathogenesis of Drug-Induced Liver Injury (DILI). Meanwhile, preclinical studies have demonstrated that tocotrienols (T3s), members of the vitamin E family, possess significant antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, suggesting a potential hepatoprotective role in various liver disorders. Clinical trials investigating Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD), a condition that shares important pathophysiological features with DILI, have also reported favorable outcomes associated with T3 supplementation. Notably, the overlap between the established mechanisms of T3s and the underlying pathophysiology of DILI provides a strong rationale for exploring the therapeutic potential of T3s in this context. Emerging evidence from studies on NAFLD further supports this approach, considering the common mechanistic pathways involved. Accordingly, this review aims to comprehensively evaluate current preclinical and clinical evidence on T3s in relation to DILI, elucidate the proposed mechanisms of action of this class of vitamin E analog, and identify key gaps in the literature that warrant further investigation.

Keywords

- antioxidants

- chemical and drug induced liver injury

- hepatoprotection

- inflammation

- oxidative stress

- tocotrienols

- vitamin E

The liver is the largest organ and plays a crucial role in the metabolism and elimination of drugs from the body. Correspondingly, the detoxification of drugs and xenobiotics by metabolizing enzymes in the liver is a crucial process for maintaining homeostasis [1]. As such, Drug-Induced Liver Injury (DILI) is defined as liver dysfunction caused by exposure to certain medications or dietary supplements that can damage hepatocytes and other liver cells [2]. Following this, DILI remains a significant clinical concern and is a major contributor to liver-related morbidity and mortality worldwide [3]. It can also imitate all forms of acute or chronic liver disease [4]. Furthermore, the incidence of DILI is estimated at approximately 19 cases per 100,000 individuals per year, accounting for a substantial proportion of hospitalizations related to jaundice and hepatitis [5]. However, the rate and severity of DILI vary between drugs, suggesting that drug-specific properties influence the risk of developing DILI [6]. A person’s susceptibility to a possible hepatotoxic drug is influenced by various factors. For instance, elderly individuals are at a higher risk of developing DILI due to prolonged medication use and heavy alcohol consumption. Additionally, women are more prone to developing autoimmune hepatitis, which can result in liver damage [2, 7]. Common culprits implicated in DILI include widely used drugs such as acetaminophen (APAP) and HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) [5]. Anticancer therapies are also recognized to elevate the risk of DILI [8]. The frequent occurrence and potential severity of DILI underscore the urgent need for effective strategies for its prevention and management.

There are two types of DILI: idiosyncratic (unpredictable) and intrinsic (direct) hepatotoxicity. Intrinsic hepatotoxicity occurs as a result of exposure to foreign agents that are directly toxic to the liver. This type of injury is typically dose-dependent and develops within a short timeframe, usually one to five days after drug exposure. However, such cases are relatively rare, occurring in approximately 1 out of every 2000 patient exposures [9]. An example of intrinsic DILI is acetaminophen (APAP) hepatotoxicity, which causes almost 50% of acute liver failure [7, 10]. Direct hepatotoxicity occurs when individuals consume slightly higher-than-recommended doses of APAP, resulting in elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels [11]. Both APAP and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) have been demonstrated to increase intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) and lipid peroxidation (LPO), which are key markers of oxidative stress and liver injury [12].

Idiosyncratic hepatotoxicity is an unpredictable and uncommon form of liver injury that is not dose-dependent and is unrelated to the pharmacological action of the drug. This type of DILI is typically influenced by factors such as age, sex, obesity, alcohol consumption, diabetes mellitus, and underlying chronic liver disease. Notably, the use of multiple medications (e.g., isoniazid, flucloxacillin, halothane, and amoxicillin), known as polypharmacy, increases the risk of DILI, particularly in older individuals [2, 13]. However, its overall incidence remains relatively low among individuals exposed to it. This limitation poses a significant challenge for further research, as the small number of affected patients reduces the feasibility of conducting large-scale clinical studies.

DILI is widely recognized as a significant cause of liver impairment and acute liver failure, making it essential to understand the mechanisms underlying this condition. The liver plays a central role in drug metabolism, and the accumulation of reactive metabolites makes it particularly susceptible to toxicity. The development of DILI primarily results from liver cell death through necrosis, apoptosis, and necroptosis, as well as from oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction [14].

Necrosis may result from oncosis, a condition characterized by the disruption of ion and water homeostasis within the cell. This disruption leads to cellular swelling and, ultimately, the rupture of the plasma membrane, resulting in the release of intracellular contents, including cytotoxic and pro-inflammatory factors, into the extracellular space. Depletion of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), caused by impaired mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, further promotes cell death. Furthermore, the release of intracellular components, such as damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), into the surrounding environment can trigger inflammatory responses. This process distinguishes necrosis from apoptosis, which is typically non-inflammatory [15]. Accordingly, diclofenac is metabolized in the liver, where phase I enzymes convert it into metabolites such as 5-hydroxydiclofenac. This metabolite undergoes further oxidation to form electrophilic quinone imine intermediates. These reactive species covalently bind to mitochondrial proteins, resulting in structural and functional impairment of the organelles. The depletion of mitochondrial glutathione (mtGSH) further enhances oxidative stress within hepatocytes, disrupting calcium homeostasis and compromising ATP synthesis. Diclofenac causes dose-dependent mitochondrial collapse, ATP depletion, and necrotic cell death, especially when glutathione (GSH) levels are depleted, playing a critical role in the development of diclofenac-induced hepatotoxicity [16].

Apoptosis is a form of programmed cell death that can occur through either the extrinsic or intrinsic pathway. The extrinsic apoptosis pathway is triggered by external signals that activate death receptors on the surface of cells, such as First Apoptosis Signal receptor (FAS) Ligand (FASL), TNF-Related Apoptosis-Inducing Ligand Receptor 1 and 2 (TRAIL-R1/R2), and Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptor 1 (TNFR1). These receptors bind to their respective ligands, TRAIL and TNF, which leads to the formation of a signaling complex that activates caspase-8. In the liver, hepatocytes naturally express high levels of these death receptors. During an immune response, CD8+ cytotoxic T cells become activated and induce apoptosis in hepatocytes by expressing FASL, which binds to FAS. This interaction activates caspase-8 and initiates the apoptotic process [17]. Flucloxacillin is metabolized in the body and can covalently bind to host proteins, forming drug-protein adducts. These adducts are subsequently broken down into peptides, some of which contain fragments of the flucloxacillin molecule. As such, the immune system may mistakenly recognize these drug-derived peptides as harmful, triggering cytotoxic CD8+ T cells to attack hepatocytes. This immune response can lead to liver injury and inflammation, potentially through the activation of the extrinsic apoptotic pathway, in which death receptor signaling induces programmed cell death in hepatocytes [18].

The intrinsic apoptotic pathway is activated in a dose-dependent manner following exposure to the drug. Most drugs are metabolized in the liver by the cytochrome P450 enzyme system, which produces reactive metabolites. These metabolites can covalently bind to mitochondrial proteins, leading to the accumulation of ROS within the mitochondria. In particular, mitochondrial dysfunction is a critical component of DILI pathophysiology. Increased ROS production contributes to mitochondrial damage and initiates a cellular stress response aimed at mitigating the injury. This response can trigger mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP), resulting in the release of cytochrome c and the activation of caspase-9, ultimately leading to apoptosis [19]. Drug metabolites and the associated oxidative stress impair normal mitochondrial function, leading to cellular energy depletion and, eventually, cell death [20].

The onset of DILI often begins with hepatic drug metabolism, which can produce reactive metabolites that directly damage liver cells. This damage may occur when these metabolites form covalent bonds with essential cellular macromolecules, disrupting normal cellular functions. A well-known example is the hepatic metabolism of APAP, which generates the toxic intermediate N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine (NAPQI) [5]. It is well known that an overdose of APAP can cause liver injury. At therapeutic doses, APAP is primarily metabolized in the liver through glucuronidation and sulfation pathways. A smaller portion is metabolized by cytochrome P450 enzymes to produce NAPQI. Under normal conditions, NAPQI is detoxified by conjugation with GSH. However, in overdose situations, GSH stores become depleted, allowing NAPQI to accumulate. This accumulation leads to oxidative stress due to the excessive production of ROS, which contributes to liver failure [21]. The elevation of ROS can trigger LPO, compromising the structural integrity of cellular membranes [20]. Consistent with this, animal studies on APAP-induced liver injury have presented elevated LPO levels [22]. Mitochondrial dysfunction has also been directly implicated in the pathogenesis of APAP-induced liver injury [23].

Necroptosis is a regulated form of necrotic cell death that occurs when apoptosis is blocked, often triggered by TNF-

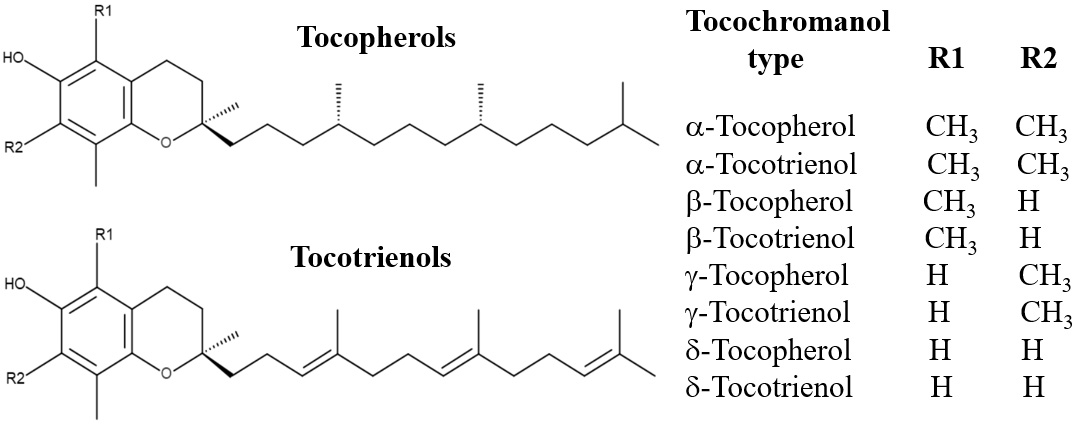

Tocopherols and Tocotrienols (T3s) are two groups of vitamin E compounds that occur naturally in various plant sources (Fig. 1). T3s are reported in a range of cereals and vegetables, including palm oil, rice bran oil, coconut oil, barley germ, wheat germ, and annatto. Among these, palm oil and rice bran oil are considered among the richest natural sources of vitamin E, particularly T3s. In addition to these, T3s are also present in other plant-based sources such as rapeseed oil, oats, hazelnuts, maize, olive oil, buckthorn berries, rye, flaxseed oil, poppy seed oil, and sunflower oil [25].

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. The chemical structures of tocopherols and tocotrienols.

Both T3s and tocopherols are fat-soluble and share a similar structural framework, consisting of a chromanol ring and a side chain attached at the C-2 position (Fig. 1). The primary difference in their side chains is that tocopherols have saturated phytyl tails, whereas T3s possess unsaturated isoprenoid side chains with three double bonds. This structural variation enables T3s to penetrate tissues with saturated fatty layers more effectively, such as the brain and liver. Moreover, T3s exhibit greater dispersion within lipid membranes, contributing to their superior biological activities [26, 27].

T3s are the primary phytonutrients present in palm oil and can be observed in a specific fraction of palm oil known as the T3-Rich Fraction (TRF). TRF comprises mostly T3s (80%), which are alpha (

T3s are known for their strong antioxidant activity, and studies indicate that they may be more effective than tocopherols in certain biological systems [31]. These compounds can inhibit the production of free radicals and the process of LPO, which are critical events in the progression of liver injury [32].

T3s exhibit antioxidant activity through both direct scavenging of ROS and indirectly enhancing the expression of antioxidant enzymes such as Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) and NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1). These enzymes help neutralize ROS and prevent oxidative damage. Their expression is regulated by the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), which plays a central role in the cellular antioxidant response. Under oxidative stress, Nrf2 is activated and translocates to the nucleus, where it binds to Antioxidant Response Elements (AREs) in the DNA to promote the transcription of genes encoding antioxidant and detoxifying enzymes, including SOD, NQO1, glutathione peroxidase (GPx), and heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1). Therefore, Nrf2 activates the expression of antioxidant enzymes, which then conduct the antioxidant defense mechanisms. This coordinated response helps the cell restore redox balance and protect against oxidative stress [34, 35, 36, 37]. Collectively, these findings suggest that T3s may enhance the liver’s natural ability to defend itself against the harmful effects of drugs.

In addition to their antioxidant effects, T3s also have strong anti-inflammatory properties [38]. They have been proven to reduce the expression of major inflammatory mediators such as tumor necrosis factor-

Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress occurs when the protein-folding capacity of the ER becomes saturated, leading to the accumulation of misfolded proteins and the activation of the unfolded protein response (UPR). Prolonged ER stress triggers hepatocyte apoptosis via pro-apoptotic mediators such as CCAAT/Enhancer-Binding Protein (C/EBP) homologous protein (CHOP). T3s exert protective effects by downregulating CHOP expression and modulating key Unfolded Protein Response (UPR) pathways, including PKR-like Endoplasmic Reticulum Kinase (PERK), Inositol-Requiring Enzyme 1 alpha (IRE1

T3s have also been demonstrated to affect lipid metabolism and support the stability of cellular membranes. They can reduce triacylglycerol levels in hepatocytes, contributing to healthier lipid profiles within the liver [42]. Their unsaturated side chain allows them to penetrate and spread efficiently within cell membranes, which helps maintain membrane integrity during cellular stress [43]. Therefore, preserving membrane structure and regulating lipid metabolism are essential for proper hepatocyte function, particularly in the context of DILI.

Recent findings indicate that T3s may influence the expression of microRNAs (miRNAs), which are small non-coding RNA molecules involved in regulating gene expression. In individuals with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), both

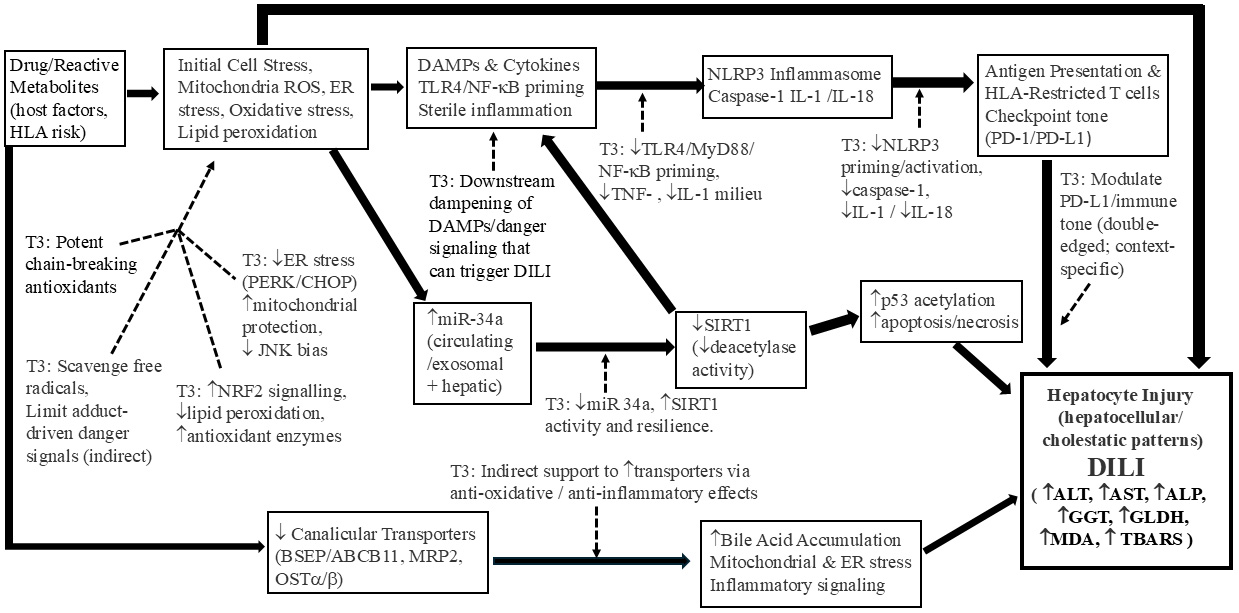

Idiosyncratic Drug-Induced Liver Injury (iDILI) arises from a complex interplay of drug-induced hepatocellular stress, activation of immune pathways, and host susceptibility factors such as human leukocyte antigen (HLA) alleles [45, 46]. Many hepatotoxic drugs generate mitochondrial ROS and LPO, processes that amplify damage signals through the release of DAMPs. Accordingly, these signals engage innate immune sensors, promote cytokine release, and facilitate adaptive immune activation, establishing a foundation for immune-mediated liver injury [47].

Redox balance plays a key regulatory role in this process. Meanwhile, Nrf2, a central transcription factor, suppresses LPO and maintains antioxidant defenses [48]. T3s, members of the vitamin E family, act as potent chain-breaking antioxidants and activate Nrf2-associated pathways. In hepatic and metabolic models, they upregulate protective enzymes such as HO-1 and NQO1, limiting oxidative stress and the generation of DAMPs [49].

Once released, DAMPs are recognized by hepatic pattern recognition receptors such as Toll-Like Receptor 4 (TLR4). This engagement activates Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-

DAMPs can also activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, amplifying IL-1

Adaptive immunity also shapes iDILI outcomes. In many cases, T cells recognize drug-modified peptides in an HLA-restricted manner. However, progression to injury depends on cytokine signals and immune checkpoint tone [53]. Notably, T3s can downregulate Programmed Death-Ligand 1 (PD-L1) and enhance T-cell activity, suggesting possible effects on immune resolution, though the balance between tolerance and injury remains uncertain [54, 55].

Some iDILI cases present as cholestatic injury due to bile salt export pump (BSEP) inhibition or immune-mediated disruption [56, 57]. While T3s have not been demonstrated to directly upregulate BSEP in humans, their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects may indirectly support transporter function [56].

MicroRNAs are essential regulators of DILI biology, modulating Nrf2, NF-

MicroRNAs, particularly miR-122 and miR-34a, are key regulators and biomarkers in human DILI, with elevated circulating and exosome-associated levels linked to hepatocyte injury and inflammation [59, 60, 61]. Hepatocyte-derived exosomes deliver miR-122 to macrophages and Kupffer cells, promoting a pro-inflammatory shift through NF-

The miR-34a-SIRT1 axis represents a central stress-response pathway. Moreover, miR-34a represses SIRT1, whereas higher SIRT1 levels protect against hepatic stress and injury [65]. DILI and iDILI pathogenesis are therefore strongly influenced by miR-122/miR-34a signaling and exosome-mediated communication [59, 63, 64]. Additionally,

T3s have been presented to influence exosome biology in oncology and immune settings.

In vitro hepatocyte studies indicate T3s protect against DILI. Using TGF-

In vivo studies using animal models have provided critical evidence for the protective effects of T3s against DILI. A summary of these findings is presented in Table 1 (Ref. [12, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81]). Early studies in the 1990s first demonstrated T3s’ potential in DILI and hepatocarcinogenesis [70, 71]. In one study, male rats were exposed to 2-acetylaminofluorene (AAF) for 20 weeks. AAF markedly increased

| Study (year) | Animals (cells) used & liver injury model | Tocotrienol form & dose | Main outcomes | Conclusion |

| Wan Ngah et al. (1991) [71] | Male Rattus norwegicus rats. Liver injury induction | A This was administered to the rats as a supplement in their diet at a dose of 0.7 mg per rat per day. | Liver microsomal GGT activity | Tocotrienols offered some protection against AAF-induced liver changes and reduced the severity and extent of neoplastic transformation in the rat livers. |

| Rahmat et al. (1993) [70] | Male Rattus norwegicus rats. Liver injury induction | A Tocotrienol was given at a dose of 30 mg | Significantly | Tocotrienols protect against chemically induced liver injury in rats by reducing neoplastic transformation, restoring glutathione-dependent enzymes and GGT toward control levels, modulating detoxification pathways, and preserving liver structure, thus reducing liver damage and preneoplastic changes, as shown by ultrastructural, morphological, and histological evidence. |

| Iqbal et al. (2004) [72] | Male Sprague–Dawley rats. Liver injury model Single dose of DEN i.p. (200 mg | T3-Rich Fraction (TRF) isolated from refined edible grade rice bran oil (RBO). (10 mg | Significant | TRF protects against hepatocarcinogenesis and liver injury by reducing lipid and protein oxidation through its antioxidant properties. Long-term supplementation lowers hepatic oxidative stress and carcinogen-induced damage, offering significant protection against liver cancer development. |

| Yachi et al. (2010) [73] | Male SD-IGS rats. Liver injury model | The T3 mix contained Each rat received 20 mg of the respective vitamin E compound as a single pre-treatment dose (6 hours before liver injury induction by CCl4). | T3 conteracts | Vitamin E analogs improve CCl4-induced liver damage in rats Reports of tocotrienols (T3s) being effective in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) suggest similar therapeutic potential for |

| Yachi et al. (2013) [76] | Male SD-IGS rats. A rat model of steatohepatitis was developed by feeding rats a high-fat diet followed by D-galactosamine (GalN) and tumor necrosis factor- In vitro model of steatohepatitis. Primary hepatocytes from rats on vitamin E-deficient diets were stimulated with TNF- | In the in vivo study, a tocotrienol mixture containing 37.8% In the in vitro study, | These effects | Tocotrienol intake inhibits lipid accumulation, inflammation, and fibrosis in the liver in this rat model of steatohepatitis, and these effects are reinforced synergistically by simultaneous intake of |

| Lee et al. (2010) [74] | Male Wistar rats. Hepatotoxicity was induced by CCl4 administration. | TRF from palm oil (oral gavage). 25 mg TRF (8 weeks). | | TRF protected rats against CCl4-induced liver injury by lowering liver enzyme levels (sGOT, sGPT), reducing oxidative stress markers, and enhancing antioxidant enzyme activity. Its effects were comparable to silymarin, suggesting TRF protects the liver by limiting oxidative damage and strengthening antioxidant defences. |

| Ayu Jayusman et al. (2014) [77] | Male Sprague-Dawley rats. Liver injury induction FNT causes liver damage | Palm oil TRF (200 mg TRF | | TRF supplementation protects liver from FNT-induced damage. TRF improves biochemical and morphological liver changes. |

| Abdella et al. (2014) [79] | Adult males laboratory mice (M. musculus). The liver injury model | Vitamin E (50 mg Vitamin E was administration Vitamin E treatment (alone or in concomitant with VPA) | | Vitamin E at 100 mg |

| Kamisah et al. (2014) [80] | Male Wistar rats. The liver injury model | Palm oil TRF (30 mg | | TRF significantly |

| Tan et al. (2015) [12] | Liver injury model | For protective effect evaluations against toxicants, concentrations of 10 & 50 mM were used for The analogs were applied using two distinct in vitro treatment approaches, both for 24 hours. | | These effects are achieved by neutralizing free radicals, alleviating mitochondrial stress, inhibiting oxidative stress and promoting body’s natural anti-oxidative defense. |

| Kamisah et al. (2015) [81] | Male Wistar rats. The liver injury model used was a high-methionine diet (1% methionine) given to rats for 10 weeks, which caused liver injury by significantly increasing plasma homocysteine levels and hepatic oxidative stress. | Palm oil TRF. TRF (mixed in diet). 30 mg The diets were given from week 6 to week 10 of the study. Throughout the entire 10-week period, all rats were also fed a high-methionine diet containing 1% methionine. | due to high-methionine diet. | TRF |

| Mostafa & Adel (2016) [75] | Male Sprague Dawley rats. Liver injury CCl4 0.5 mL/kg i.p. (2 | T3 (60 mg T3 control group Treatment group Protection group | TE supplementation can have beneficial effects on liver functions and an effective role for the prevention of CCl4 induced hepatic damage in rats. | |

| Ayu Jayusman et al. (2017) [78] | Male Sprague-Dawley rats. Liver injury induction | Palm oil TRF. (200 mg TRF | | TRF protects against FNT-induced liver damage. Further studies needed to explore underlying mechanisms and recovery levels. |

Footnote:

The effect of TRF from rice bran oil in a rat model of liver cancer induced by DEN and AAF had been evaluated [72]. Carcinogen exposure caused marked liver alterations and changes in alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and glutathione S-transferase (GST), sensitive markers of preneoplastic and neoplastic progression. The study linked these effects to oxidative stress, highlighting LPO and malondialdehyde (MDA) as drivers of carcinogenesis. Notably, TRF significantly reduced tumour development, with protection attributed to its antioxidant activity in lowering LPO and protein oxidation. These findings suggest TRF mitigates oxidative stress-mediated hepatocarcinogenesis [72].

T3s protect against chronic carbon tetrachloride (CCl4)-induced liver injury by reducing oxidative stress, lowering plasma ALT, and decreasing the incidence of fatty liver. They also limit Triglyceride (TG) accumulation and liver enlargement, likely through effects on lipid metabolism and enzyme activity.

T3 treatment in a TNF-

Fenitrothion (FNT) administration (20 mg

Vitamin E demonstrates protective effects against valproic acid (VPA)-induced chromosomal changes in mice. The mice were divided into control, VPA-treated, and vitamin E groups. Animals received oral doses of 50, 100, or 200 mg

TRF from palm oil demonstrates hepatoprotective potential in a phenylhydrazine-induced liver injury model. In male Wistar rats, TRF (30 mg

Emerging clinical research has started to investigate the potential benefits of T3s on human liver function, particularly in relation to NAFLD. In individuals diagnosed with NAFLD, supplementation with

Another clinical trial investigated the effects of mixed palm T3s in hypercholesterolemic patients with ultrasound-proven NAFLD [82]. The results of this study indicated that treatment with mixed T3s led to a significant normalization of the hepatic echogenic response, a measure of fat content in the liver, compared to the placebo group [82]. This finding suggests a potential for T3s to directly impact the accumulation of fat in the liver. Furthermore,

Although preclinical studies and clinical trials in NAFLD have demonstrated encouraging results, there remains a limited number of clinical investigations specifically examining T3s for the treatment of DILI. Current literature suggests potential hepatoprotective effects of

| Authors | Study design | Population | Tocotrienol isoform & dosage | Duration | Key findings | Conclusion |

| Pervez et al. 2018 [3] | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled | NAFLD patients | 600 mg/day | 12 weeks | Decreased serum aminotransferases (ALT: –13.0; AST: –8.77), hs-CRP (–0.74), MDA (–0.89), FLI score (–9.41). No improvement in hepatic steatosis on ultrasound. | |

| Magosso et al. 2013 [82] | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled | Hypercholesterolemic adults with NAFLD | Mixed T3 400 mg/day | 1 year | A significantly higher normalisation of hepatic echogenic response in the tocotrienols-treated group (50%) compared to the placebo group (23.5%). | Mixed T3 |

| Thendiono 2018 [84] | Interventional comparative study design | NAFLD patients | Mixed Tocotrienol 100 mg/day plus lifestyle modification | 3 months | Mixed tocotrienols significantly decreased liver stiffness measurement (LSM) among NAFLD patients (79%). | T3 |

| Pervez et al. 2020 [83] | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled | NAFLD patients | 600 mg/day | 24 weeks | Reduced FLI (–12.82), HOMA-IR (–0.52), hs-CRP 9 (–0.6), MDA (–0.91), ALT (–8.86), AST (–6.6). Reduced hepatic steatosis. | |

| Nawawi et al. 2022 [85] | Interventional comparative study design | Patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) | Palm oil TRF 50 mg/day | 6 months | Significant reduction in ALT (–37.4 U/L) and AST (–9.5 U/L) levels observed. Improvement in hepatic steatosis (+0.36) and inflammation (+0.19) scores noted. | TRF |

Nevertheless, there are significant key differences between DILI and NAFLD that cannot be ignored. In NAFLD, metabolic stress is central: chronic nutrient excess and insulin resistance drive hepatic lipotoxicity. This leads to ER stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and sterile inflammation, consistent with the “multiple parallel hits” model that incorporates adipose lipid flux and gut-liver interactions [86, 87, 88]. By contrast, DILI is usually initiated by xenobiotics. Drugs or their metabolites can induce injury through reactive metabolite formation, mitochondrial or ER stress, or bile acid dysregulation, such as BSEP inhibition. Meanwhile, in iDILI, adaptive immune responses (modulated by HLA risk alleles) play a critical role, consistent with the “hapten” and “danger” models [2, 45, 46]. Despite distinct triggers, both NAFLD and DILI converge on oxidative/ER stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and inflammatory signalling. The significant difference is that NAFLD reflects chronic metabolic overload, whereas DILI arises from a specific xenobiotic exposure. Moreover, iDILI involves an abrupt, antigen/HLA-restricted immune component. Conversely, NAFLD inflammation is metabolically programmed, whereas iDILI immunity is host- and antigen-specific [45, 87]. There is a mechanistic link between NAFLD and several forms of DILI that justifies using T3s as a potential therapeutic treatment. However, there are apparent exceptions, particularly for immune-mediated iDILI and DILI caused by transporter-blocked cholestasis. Extrapolation is justified where oxidative/ER stress, mitochondrial injury, inflammasome activation, and miRNA signatures dominate, particularly in intrinsic DILI and drug-induced steatohepatitis. Still, it is not warranted for HLA-restricted iDILI (immune-driven) or BSEP-block cholestasis (transporter-related), since T3s are unlikely to address the underlying cause. This argues for adjunctive (not replacement) use of T3 in carefully phenotyped DILI, supported by mechanistic biomarkers to confirm target engagement.

T3s have demonstrated encouraging effects in advanced liver disease, particularly in slowing progression toward cirrhosis. Although research remains at an early stage, emerging studies highlight potential mechanisms and clinical benefits. The most notable investigation examined T3 supplementation in patients with End-Stage Liver Disease (ESLD) awaiting transplantation [89]. Using the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score, a standard tool for assessing chronic liver disease severity and transplant priority, the study revealed that oral T3 supplementation reduced MELD scores in 50% of treated patients. This is compared with only 20% in those given

Based on the preclinical and clinical studies discussed above, it could be summarized that T3s help protect the liver from drug-induced damage mainly through their strong antioxidant properties. Specifically, they lower oxidative stress, reduce the formation of ROS and LPO, and increase the activity of natural antioxidant defenses such as reduced glutathione, SOD, catalase, and GPx. In addition, T3s help normalize elevated liver enzymes, including ALT, AST, and GGT, and improve liver tissue viability by reducing fat accumulation (steatosis), cell death (necrosis), and structural damage. They also suppress inflammation by decreasing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-

| Mechanism | Supporting Evidence | References |

| Scavenging Reactive Oxygen Species and Reducing Oxidative Stress | Potent antioxidant activity, inhibits free radical production and lipid peroxidation, | Tan et al. 2015 [12] |

| Modulating Inflammatory Pathways | Possesses anti-inflammatory properties, inhibits expression of TNF- | Yachi et al. 2013 [76] |

| Potential for Enhancing Cellular Defense Mechanisms (e.g., Nrf2 Activation) | TRF activates Nrf2 pathway in mouse liver, leading to increased expression of antioxidant and cytoprotective genes. | Atia et al. 2021 [34] |

| Impact on Lipid Metabolism and Cellular Membrane Integrity | Influences lipid metabolism, reduces triacylglycerol levels in hepatocytes, efficiently penetrates and distributes within cell membranes. | Pervez et al. 2018 [3] |

| Regulation of MicroRNA Expression | δ-T3 and | Pervez et al. 2022 [44] |

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Tocotrienol-mediated mechanisms for the prevention and limitation of drug-induced liver injury (DILI). The filled arrows represent the mechanistic pathways involved in DILI, in which the thicker size of the arrows represent the more important mechanistic pathways in DILI pathogenesis. The broken arrows represent the effect of tocotrienols in mitigating DILI at the various mechanistic steps.

Current research has identified several crucial gaps that need to be considered when examining how T3s may help treat DILI. One major issue is that most studies have focused on how T3s work in NAFLD, not in DILI specifically. Although both NAFLD and DILI involve factors such as inflammation and oxidative stress, their underlying causes and patterns of disease progression differ significantly [40]. Due to these aspects, results from NAFLD studies cannot be directly applied to DILI, and additional research is required to understand how T3s affect drug-related liver damage.

One notable limitation is the low bioavailability of T3s, which may reduce their effectiveness when taken orally [25]. This issue suggests the need to investigate alternative formulations or delivery methods that could improve absorption and increase their concentration in target tissues [91]. In addition, existing studies vary widely in terms of T3 dosage and treatment duration, making it challenging to determine the most effective approach for managing liver injury [49]. Moreover, large-scale randomized controlled trials are still limited, especially those that examine liver injury other than NAFLD. The diversity in study populations and the types of DILI studied further complicates efforts to draw clear conclusions from current evidence.

In intrinsic DILI, T3s protect the liver mainly by reducing oxidative/ER stress and inflammation. They lower mitochondrial ROS, enhance Nrf2-dependent defenses (HO-1, NQO1), and suppress NF-

In iDILI, T3s may protect by controlling oxidative stress, dampening TLR4–NF-

Future research on T3s in DILI should prioritize well-designed clinical trials that assess the effects of specific isoforms across different types of DILI. Determining optimal dosage, duration, and formulations that enhance bioavailability will be crucial, as will evaluating their potential synergy with current DILI treatments. Studies should also investigate the molecular pathways underlying their hepatoprotective actions, focusing on isoform-specific effects. Additionally, assessing the preventive potential of T3s in high-risk individuals could expand their clinical relevance. Ultimately, targeted clinical trials are needed to validate preclinical findings and insights gained from related conditions such as NAFLD.

T3s show promise as therapeutic agents in DILI by addressing major pathogenic mechanisms. Their strong antioxidant properties neutralize ROS and reduce LPO, protecting hepatocytes from reactive drug metabolites. They may also preserve mitochondrial integrity, vital for cell survival under toxic stress, and exert immunomodulatory effects that could benefit immune-mediated DILI. Additionally, evidence from clinical studies in NAFLD suggests T3s protect the liver in humans, supporting their potential relevance for DILI. Despite these encouraging findings, a shortage of well-designed clinical trials specifically focused on evaluating the role of T3s in DILI remains. Therefore, addressing this gap should be a priority in future research to establish the therapeutic value of these approaches in this context.

AA conceived and initiated the review, designed the study framework, and supervised the project. NAMF provided guidance, critical advice, and contributed to the conceptual development of the manuscript. NSSMN, MRAR, JAH, and FZJS conducted literature searches, drafted sections of the manuscript, and assisted with data compilation and synthesis. AA and NAMF critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors contributed to editorial changes, read, and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

All authors of the manuscript are immensely grateful to Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, and especially to the staff of the Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine, for their technical assistance and invaluable support in completing this project.

The author acknowledges the Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS), grant number FRGS/1/2020/SKK0/UKM/02/14, funded by the Ministry of Higher Education (MOHE), Malaysia, and part of the author’s research expenditure is supported by the Geran Fundamental Fakulti Perubatan (GFFP), grant number FF-2020-240, conferred by the Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

While preparing this manuscript, the authors utilized ChatGPT-4 to help identify spelling and grammatical issues. Following this, all content was carefully reviewed and edited by the authors, who assume full responsibility for the final version of the manuscript.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.