1 Department of Gynecology, Clinical Medicinal College of Dali University, 671000 Dali, Yunnan, China

2 Department of Gynecology, Fenghuang People's Hospital, 416200 Fenghuang, Hunan, China

3 Department of Pharmacy, Yunnan Provincial Key Laboratory of Entomological Biopharmaceutical R&D, Dali University, 671000 Dali, Yunnan, China

Abstract

To observe the cytotoxic effects of the Blaps rynchopetera Fairmaire (BRF) ethyl acetate extract on the human ovarian carcinoma cell line SKOV3.

SKOV3 cells were exposed to 0 μg/mL (control), 5 μg/mL, 10 μg/mL, 25 μg/mL, 50 μg/mL, or 100 μg/mL BRF ethyl acetate extract for 2 h, 6 h, 12 h, 24 h, 36 h, or 48 h. SKOV3 cell viability was evaluated using a cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) assay. β-catenin, cyclin D1, and p21 protein levels were detected via Western blotting. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and CD34 protein was detected via immunohistochemistry.

BRF ethyl acetate extract inhibited the viability of SKOV3 cells in a dose- and time-dependent manner. The IC50 of the BRF ethyl acetate extract for SKOV3 cells was 13.07 μg/mL. The cell viability was lowest after exposure to the BRF ethyl acetate extract for 48 h. β-catenin, cyclin D1, and p21 protein levels decreased in a time-dependent manner and were lowest after exposure to the 10 μg/mL BRF ethyl acetate extract. VEGF and CD34 protein staining intensity and the number of positive cells were the lowest after exposure to the 10 μg/mL BRF ethyl acetate extract.

BRF ethyl acetate extract may exert antitumor effects on ovarian cancer by suppressing tumor cell proliferation and angiogenesis.

Keywords

- angiogenesis

- Blaps rynchopetera Fairmaire

- ethyl acetate

- growth

- ovarian cancer

Ovarian cancer is a common malignant tumor of the female reproductive system that is often diagnosed at a late stage. The average 5-year survival rate for patients with ovarian cancer is approximately 48.6%, ranging from 92.6% for patients with ovarian cancer diagnosed at the local stage to 30.2% for patients with metastasized ovarian cancer [1].

In 2019, China reported approximately 196,000 existing cases of ovarian cancer, with 45,000 newly diagnosed cases and 29,000 fatalities attributed to the disease [2]. Between 1990 and 2019, the prevalence, incidence, mortality, and morbidity of ovarian cancer in China increased 3-fold, while these measures of disease burden remained relatively constant globally.

The conventional treatment for ovarian cancer involves a combination of chemotherapy and surgery. This treatment aims to achieve maximal cytoreduction; however, an estimated 80% of individuals diagnosed with late-stage ovarian cancer experience tumor progression or recurrence with varied responses to subsequent platinum-based chemotherapy. Meanwhile, targeted therapies may be used for maintenance to prevent the growth of residual cells or for recurrent cases [1].

The progression and recurrence of ovarian cancer are modulated by the tumor microenvironment, which promotes tumor cell growth, invasion, and migration, as well as immune responses and angiogenesis [3]. Apoptosis and angiogenesis in tumor cells are potential therapeutic targets in ovarian cancer; however, there remains a critical unmet clinical need for innovative therapeutic approaches that improve patient prognosis [4, 5].

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) has been widely utilized to manage various types of cancer. TCM-based antitumor medicines include extracts derived from herbs, fungi, and insects that cause tumor cell cycle perturbations [6], induce apoptosis, and inhibit angiogenesis. However, the method used to extract the bioactive compounds can affect the yield, phytoconstituents, and cytotoxicity of the resulting extract [7].

Thus, TCM uses an ethyl acetate extract to treat various systemic tumors. An ethyl acetate (EtOAc) extract of U. longissima is thought to be a therapeutic agent against the formation of esophageal and gastric adenocarcinoma [8]. The ethyl acetate extract of Sculellaria barbata (barbed skullcap) showed obvious antiangiogenic activity in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) [9]. The administration of water extract of F. carica L. can inhibit the formation of new blood vessels and inhibit VEGF expression [10].

Blaps rynchopetera Fairmaire (BRF) is an important medicinal insect used in Yunnan Province [11] and belongs to the Tenebrionidae (Coleoptera) family of beetles. BRF has antibacterial and antioxidant properties and demonstrates anticancer activity by suppressing tumor cell growth and angiogenesis [12]. The ethyl acetate extract of BRF has shown significant cytotoxicity against the breast cancer cell lines MD-A-MB-231 and SKBR3, the pancreatic cancer cell line ASPC1, and the prostate cancer cell line PC3. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the cytotoxic impact of a BRF ethyl acetate extract on the human ovarian carcinoma cell line SKOV3.

A total of 2000 g of live adult BRF was provided by Professor Yang Yongshou from the Research Institute of Insect Medicine and Biology, Dali University. Human SKOV3 ovarian carcinoma cells (item number: SC154) were purchased from Beijing Ita Biological Co., Ltd., China.

For extraction, 2000 g of live adult BRF was soaked in 60% ethyl alcohol for 1 hour. BRFs were mashed and placed back in the soaking solution for 96 h. The mixture was subsequently centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 5 min. The pellet was washed 3 times, and the pooled supernatants were centrifuged at 4000 rpm and 50 °C until the solvent smell had completely evaporated. The resulting supernatant was added to 1 L of petroleum ether, trichloromethane, or ethyl acetate. The ethyl acetate extract was collected, verified through high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis, and lyophilized. The yield was calculated, and the lyophilized extract was stored at –20 °C.

SKOV3 cells were thawed in a water bath at 37 °C, plated in a T25 tissue culture flask with Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) and 10% fetal bovine serum, and cultured in 5% CO2 at 37 °C until the cells were at the logarithmic growth stage (cell coverage rate 80% to 90%). The cell line was validated via short tandem repeat (STR) profiling and tested negative for mycoplasma.

SKOV3 cells (2

SKOV3 cells were exposed to 0 µg/mL (control), 5 µg/mL, 10 µg/mL, 25 µg/mL, 50 µg/mL, or 100 µg/mL BRF ethyl acetate extract for 48 h or 10 µg/mL BRF ethyl acetate extract for 2 h, 6 h, 12 h, 24 h, 36 h, or 48 h. The cells were subsequently washed 3 times with 5 mL of cold PBS (0.01 M, pH 7.2–7.3). The overall protein content within the cells was quantified using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein detection kit (PICPI23223, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Following quantification, 10 µg protein samples were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate‒polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). The separated proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane. Nonspecific binding sites on the membrane were stripped with Tris–HCl buffer salt solution–Tween 20 (TBST) and blocked with skimmed milk at room temperature for 30 min. The membrane was incubated sequentially with primary (

A total of 1 mL of 2

The VEGF or CD34 immunoreactivity was yellow, brownish yellow, or brown. The staining intensity was evaluated as follows: 0 for no staining, 1 for weak staining (light yellow), 2 for moderate staining (brownish yellow), and 3 for strong positive staining (brown). The proportion of positive cells was scored as 0 (0–5%), l (6–25%), 2 (26–50%), 3 (51–75%), or 4 (

Data analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Prism 9.4.2, GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) and SPSS v21.0 (International Business Machines Corporation (IBM), Armonk, NY, USA). Data normality was assessed using the Shapiro‒Wilk test. Variables that followed a normal distribution are expressed as the mean

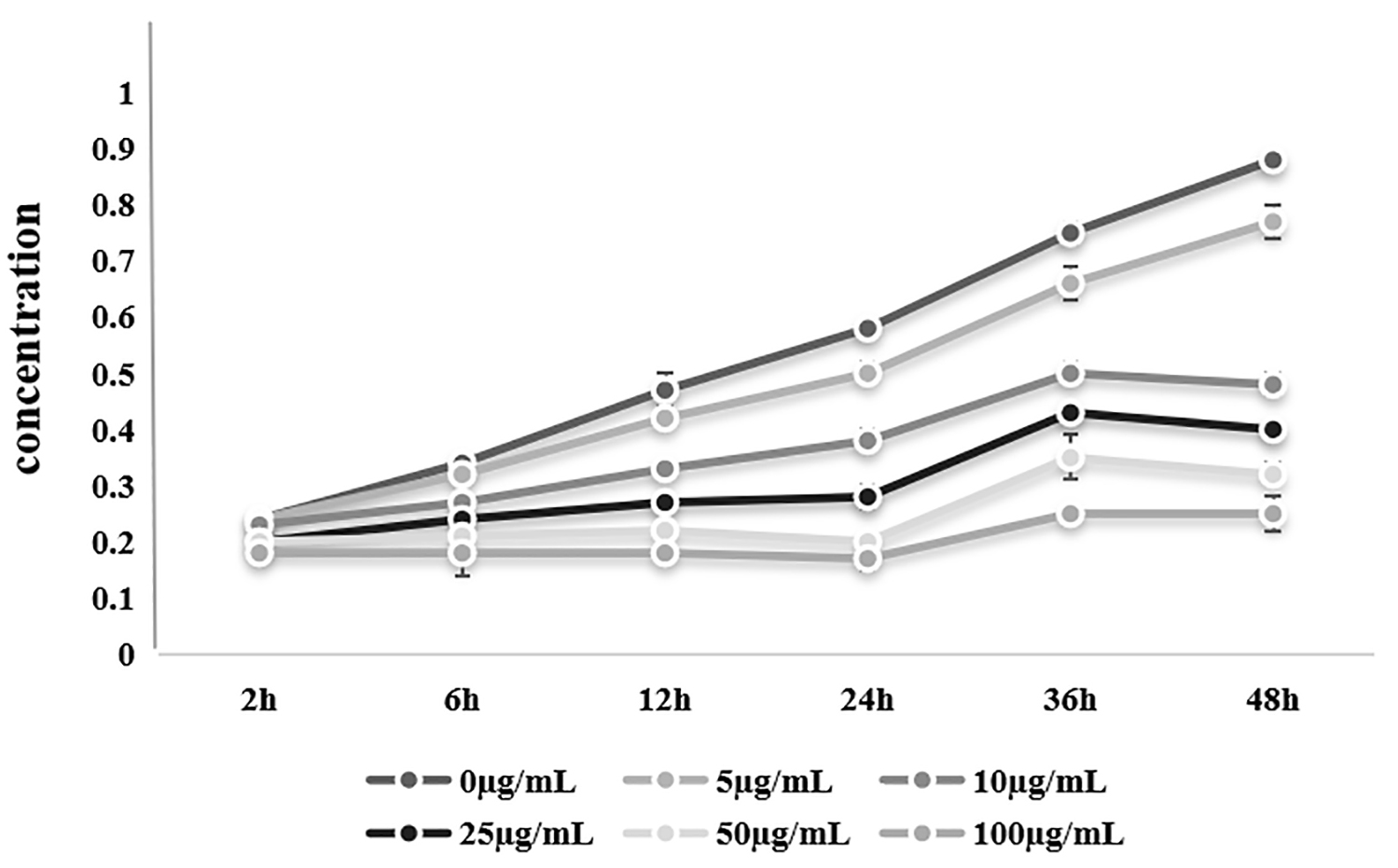

The CCK-8 assay was used to detect the viability of SKOV3 cells exposed to 0 µg/mL (control), 5 µg/mL, 10 µg/mL, 25 µg/mL, 50 µg/mL, or 100 µg/mL BRF ethyl acetate extract for 2 h, 6 h, 12 h, 24 h, 36 h, or 48 h.

SKOV3 cell viability decreased as the concentrations of the BRF ethyl acetate extract increased (100 µg/mL vs. 0 µg/mL: F = 33.3; p = 0.018). Furthermore, SKOV3 cell viability decreased as the exposure time increased across all the concentrations of the BRF ethyl acetate extract (10 µg/mL vs. 0 µg/mL: F = 132.6; p

| Time (h) | 0 µg/mL | 5 µg/mL | 10 µg/mL | 25 µg/mL | 50 µg/mL | 100 µg/mL |

| 2 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.18 |

| 6 | 0.34 | 0.32 | 0.27 | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.18 |

| 12 | 0.47 | 0.42 | 0.33 | 0.27 | 0.22 | 0.18 |

| 24 | 0.58 | 0.50 | 0.38 | 0.28 | 0.20 | 0.17 |

| 36 | 0.75 | 0.66 | 0.50 | 0.43 | 0.35 | 0.25 |

| 48 | 0.88 | 0.77 | 0.48 | 0.40 | 0.32 | 0.25 |

Note: * p

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Effect of Blaps rynchopetera Fairmaire (BRF) ethyl acetate extracts on SKOV3 cell viability.

The IC50 of the BRF ethyl acetate extract for SKOV3 cells were 13.07 µg/mL (Supplementary Fig. 1). The cell viability was lowest after 48 h of BRF ethyl acetate extract exposure (5–50 µg/mL vs. 0 µg/mL: F = 479.5; p

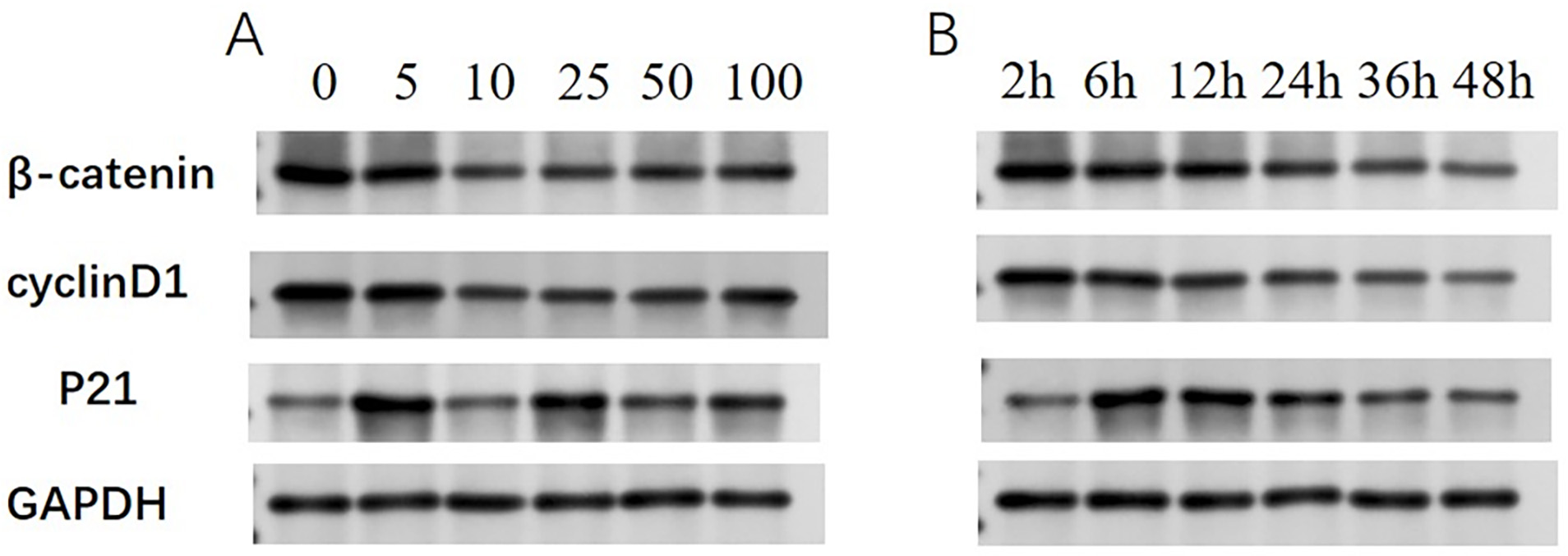

Western blotting was used to investigate the effects of the BRF ethyl acetate extract on

Initially, SKOV3 cells were exposed to 0 µg/mL (control), 5 µg/mL, 10 µg/mL, 25 µg/mL, 50 µg/mL, or 100 µg/mL BRF ethyl acetate extract for 48 h. The

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Expression of

Subsequently, the dynamic changes in

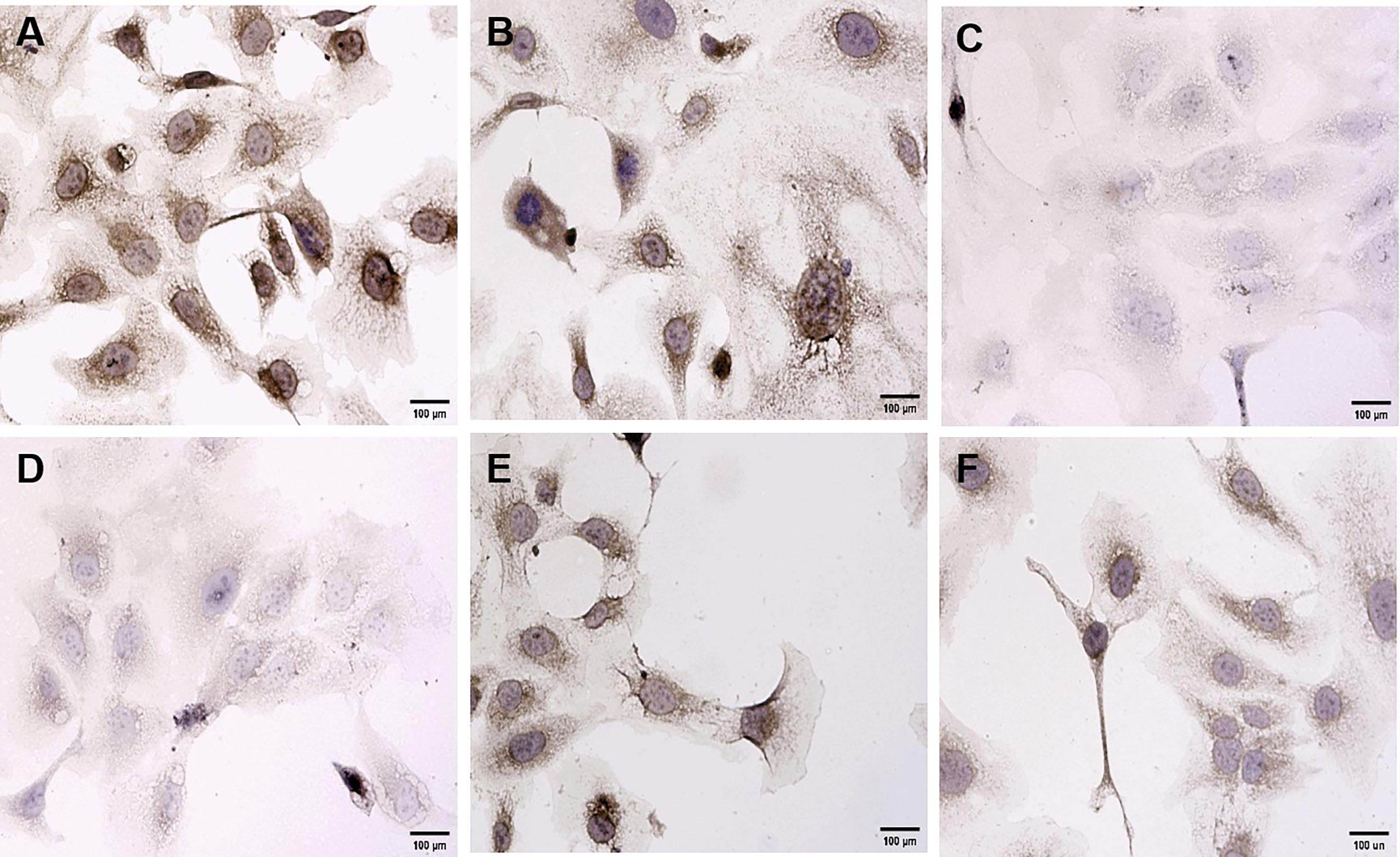

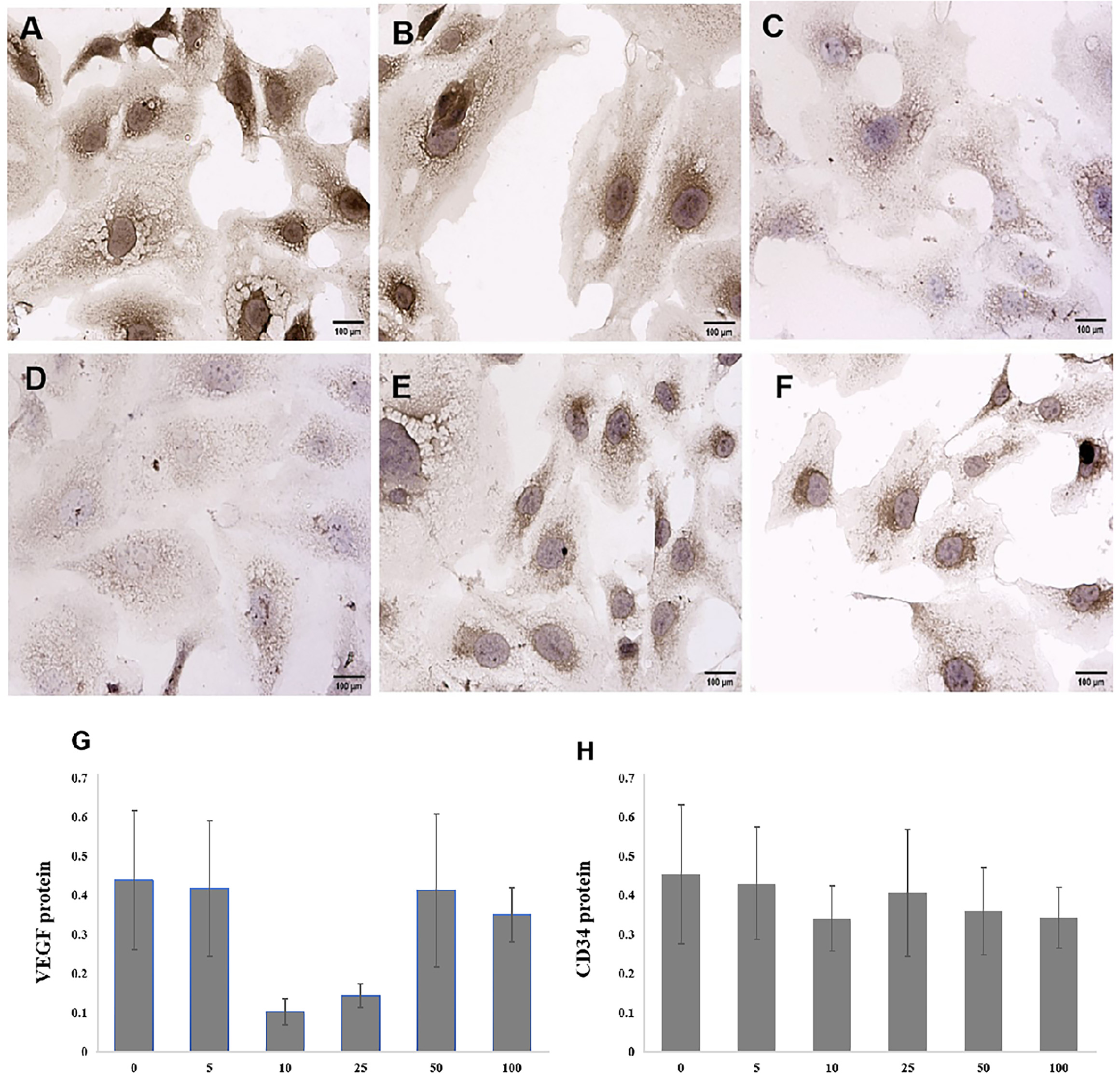

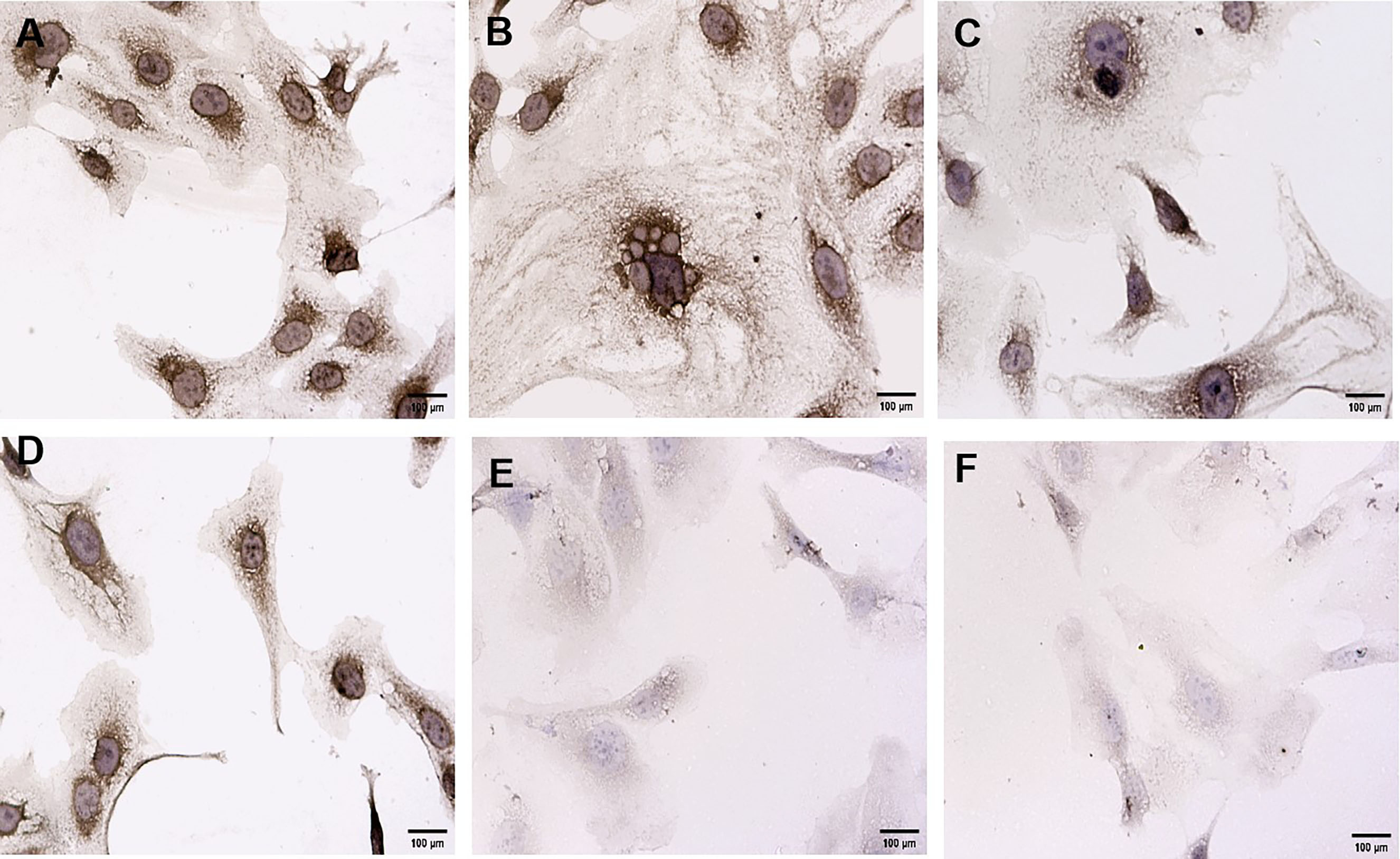

Immunohistochemistry was used to investigate the effects of the BRF ethyl acetate extract on VEGF and CD34 protein expression in SKOV3 cells. Initially, SKOV3 cells were exposed to 0 µg/mL (control), 5 µg/mL, 10 µg/mL, 25 µg/mL, 50 µg/mL, or 100 µg/mL BRF ethyl acetate extract for 48 h. A marked positive expression of the VEGF and CD34 proteins was observed in the cytoplasm of the SKOV3 cells. The VEGF and CD34 protein staining intensities and number of positive cells were lowest in the SKOV3 cells exposed to 10 µg/mL BRF ethyl acetate extract (Figs. 3,4).

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Effects of treatment with different concentrations of the BRF ethyl acetate extract for 48 h on vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) protein expression in SKOV3 cells (200

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Effects of different concentrations of the BRF ethyl acetate extract for 48 h on CD34 protein expression in SKOV3 cells (200

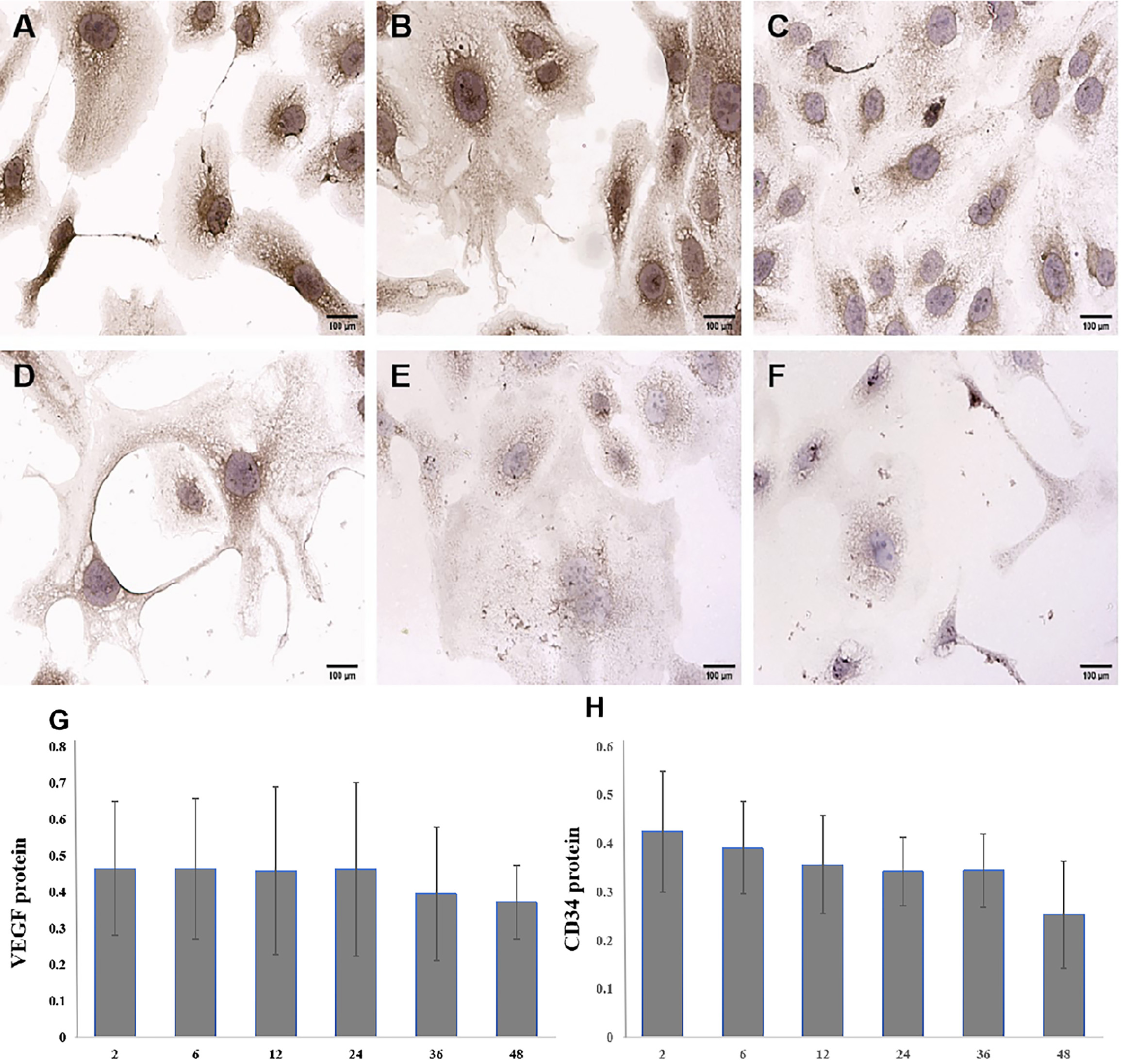

Subsequently, dynamic changes in VEGF and CD34 protein expression was explored in SKOV3 cells exposed to 10 µg/mL BRF ethyl acetate extract for 2 h, 6 h, 12 h, 24 h, 36 h, or 48 h. VEGF and CD34 protein expression decreased in a time-dependent manner in SKOV3 cells exposed to 10 µg/mL BRF ethyl acetate extract (Figs. 5,6).

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. Dynamic changes in VEGF protein expression in SKOV3 cells exposed to 10 µg/mL BRF ethyl acetate extract (200

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6. Dynamic changes in CD34 protein expression in SKOV3 cells exposed to 10 µg/mL BRF ethyl acetate extract (200

TCM plays a significant role in the prevention and management of various cancers [14]. This study revealed the cytotoxic effects of a BRF ethyl acetate extract on the human ovarian carcinoma cell line SKOV3. BRF is an insect with therapeutic value derived from the Yunnan–Guizhou Plateau of China that has anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antitumor, and immune-boosting properties. In the present study, the BRF ethyl acetate extract suppressed SKOV3 cell viability in a dose- and time-dependent manner. The protein levels of

The main active ingredients of BRF include polysaccharides, dipeptides, and phenolics [15]. Notably, phenolic compounds exhibit potent antioxidant activity both in vitro and in vivo [16]. Phenolic antioxidants can disrupt the oxidation process by acting as free radical scavengers or by chelating metal ions, thereby lowering the risk of certain health disorders, including cancer [13].

The ethyl acetate phase of medicinal plant extracts, such as Saussurea grandifolia (chwinamul) [17], Spatholobus littoralis Hassk (bajakah tampala plant) [18], and Artemisia biennis Willd. (Compositae) [19] have high total phenolic contents and 1-diphenyl-2-picrohydrazide (DPPH) radical scavenging activity. The ethyl acetate extracts of several medicinal plants, including Polygonum perfoliatum L (Asiatic tearthumb), Avena sativa L. [20] (fermented oats), and Achillea millefolium L. [21], have been shown to exhibit antitumor activity on breast cancer MCF-7 cells, hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells, cervical HeLa cells, non-small cell lung A549 cells, chronic myelogenous leukemia K562 cells, epidermoid carcinoma A431 cells, gastric cancer SGC-7901 cells, prostate cancer PC-3 cells, colon carcinoma HT-29 cells, glioma BT-325 cells, and pancreatic cancer PANC-1 cells. The antitumor effects of these extracts may be due to the antioxidant properties of phenolic compounds, which inhibit the cell cycle and apoptosis, and suppress tumor proliferation and angiogenesis.

Similarly, the antitumor effects of BRF ethyl acetate in ovarian cancer may be due to the phenolic composition of BRF. Insects incorporate plant phenolic compounds while consuming leaves and other plant tissues. Insects are also able to produce phenolic compounds endogenously and integrate these compounds into their cuticle during sclerotization [22]. Anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antitumor, and antimicrobial properties have been documented for the primary phenolic compounds present in insects, indicating that these compounds, acquired through the diets of insects, retain their biological activity. Additional research is needed to analyze the phenolic composition of adult BRF and evaluate the physiological impacts of BRF [16].

The classic Wnt/

The Wnt/

Angiogenesis is the development of a network of blood vessels that penetrate cancers. Hence, angiogenesis supplies oxygen, essential nutrients, and growth factors while also promoting the spread of tumors to remote organs [31, 32]. VEGF and CD34 are important mediators of angiogenesis. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are generated in response to proangiogenic factors, including VEGF, and are involved in VEGF receptor autophosphorylation and signaling pathways, leading to the induction of the transcription factors and genes involved in angiogenesis [33]. This study identified that the BRF ethyl acetate extract reduced VEGF and CD34 protein expression in SKOV3 cells. The underlying molecular mechanisms are unclear but may involve phenols in the BRF ethyl acetate extract decreasing ROS levels, altering VEGF expression and signaling pathways, and subsequently reducing vascular density. Similarly, Lichong Shengsui Yin (LCSSY), which consists of Curcumae rhizome, Sparganii rhizome, Astragali radix, and others, is an effective TCM prescription for ovarian cancer, inhibiting the growth of ovarian cancer via the downregulation of VEGF.

In conclusion, this study revealed that the BRF ethyl acetate extract suppressed proliferation and angiogenesis in ovarian cancer cells and has potential as a novel, targeted low-dose treatment strategy for ovarian cancer. Nonetheless, further research is needed to clarify the molecular pathways responsible for the antitumor effects of the BRF ethyl acetate extract in ovarian cancer.

The datasets generated during and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

CL: Data curation, Formal analysis; XC: Writing—original draft, Make figures and tables, Search references; CZ: Perform the research, Resources, Software; HL: Design of the work, Project administration, Resources, Acquisition, Analysis, Writing—review & editing. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The reasaerch was done in lab of the First Affiliated Hospital of Dali University. All procedures in this study were conducted in accordance with the regulations of the First Affiliated Hospital of Dali University Ethics Committee (Approval number: DFY20210417001).

We thank Medjaden Inc. for assisting in the preparation of this manuscript.

This work was funded by grants from the Master’s Scientific Fund Project of the Education Department of Yunnan Province (reference: 2022Y860) and the Dali University Research and Development Fund (reference: FZ2023YB036).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/IJP43873.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.