1 Department of Nostology, Qingdao Municipal Hospital, 266071 Qingdao, Shandong, China

2 Department of Cardiology, Qingdao Municipal Hospital, 266071 Qingdao, Shandong, China

Abstract

Sodium arsenite, a pesticide, is well known to induce cardiotoxicity via myocardial apoptosis. Fisetin, a plant, has antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic potential. This study aimed to evaluate the putative mechanism of action of fisetin against sodium arsenite-induced cardiotoxicity in experimental rats.

Cardiotoxicity was induced in male Sprague-Dawley rats (200–230 g, n = 15, in each group) using sodium arsenite (5 mL/kg, p.o., 28 days) and concomitantly treated with either coenzyme Q10 (10 mg/kg) or fisetin (5, 10 and 25 mg/kg, p.o.) orally for 28 days. Various biochemical, molecular, and histopathological analyses were performed to evaluate the efficacy of fisetin against cardiotoxicity. Data were analyzed by one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), while Tukey’s multiple range tests were applied for post hoc analysis.

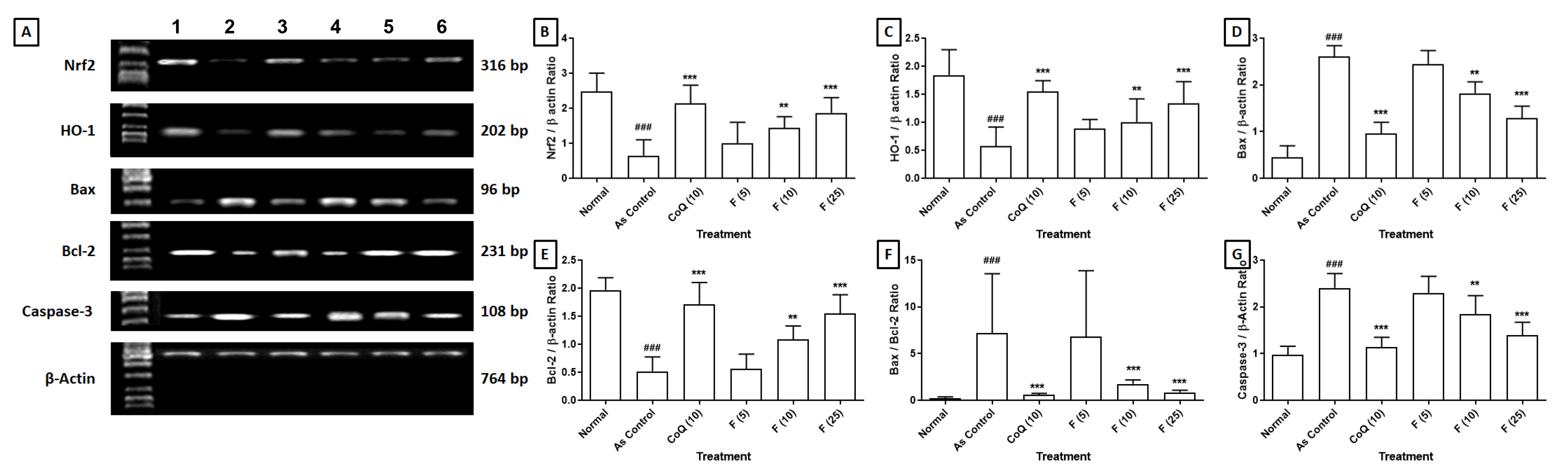

Chroni carsenite administration promoted a significant (p < 0.001) increase in relative heart weight and alterations in electrocardiographic, hemodynamic, and left ventricular function parameters, which were effectively and dose-dependently attenuated (p < 0.01 and p < 0.001) by fisetin (10 and 25 mg/kg). Moreover, fisetin treatment also markedly decreased elevated serum creatine kinase-MB (CK-MB), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), and lipid levels. Arsenite-induced elevated cardiac oxido-nitrosative stress was also efficiently and dose-dependently decreased (p < 0.01 and p < 0.001) by fisetin. Following arsenite exposure, the mRNA expressions of cardiac nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1) and B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) were downregulated, and Bax and Caspase-3 mRNA were up-regulated; these expressions were likewise effectively and dose-dependently (p < 0.01 and p < 0.001) inhibited by fisetin. Histopathological observations of the heart suggested that fisetin attenuated arsenite-induced myocardial aberrations.

Fisetin effectively mitigates sodium arsenite-induced cardiotoxicity in experimental rats. The protective effects of fisetin are associated with antioxidant (Nrf2/HO-1) and apoptotic (Bax/Bcl-2 and caspase-3) pathways in experimental rats. Thus, fisetin can be considered a potential phytoconstituent in managing pesticide-induced cardiotoxicity.

Keywords

- apoptosis

- cardiotoxicity

- fisetin

- heme oxygenase 1

- nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor-2

- sodium arsenite

Sodium arsenite is a common inorganic arsenic compound used as a pesticide in

dyeing and soap industries [1]. It’s a listed hazardous substance by the

Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and is well known to induce

cardiotoxicity [2]. Arsenic exposure, whether through environmental

contamination, occupational exposure or intentional ingestion, has been

associated with adverse cardiovascular effects resulting from alteration of ion

channel function and intracellular calcium equilibrium, leading to

electrocardiographic abnormalities to irreversible degenerative cardiomyopathy

and congestive heart failure [3, 4]. The escalating incidence of cardiovascular

diseases in China led to 4 million fatalities in 2016, with reported

hospitalization costs for acute myocardial infarction reaching 19 billion

Renminbi (RMB) (approx. 3 billion United States Dollar (USD)) [5, 6, 7]. Furthermore,

the annual hospitalization costs from cardiovascular disease (CVDs) in other

Southeast Asian countries, such as South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand and Malaysia,

are

Studies have well-documented the pathophysiology of sodium arsenite-induced cardiotoxicity [1, 2]. Prolonged exposure to sodium arsenite generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) through various mechanisms, including the inhibition of antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione peroxidase (GPx) [9, 10]. Excessive ROS production can lead to oxidative stress, causing damage to cellular components such as lipids, proteins and deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) within cardiac cells [11]. Additionally, arsenic exposure can disrupt mitochondrial function and impair oxidative phosphorylation, decreasing adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production and mitochondrial membrane potential [12]. Mitochondrial dysfunction further contributes to cellular energy depletion, calcium dysregulation and increased production of ROS, exacerbating oxidative stress and cardiotoxicity [13]. Researchers suggested chronic exposure to sodium arsenite induces myocardial apoptosis through various pathways, including activating caspases, mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis and oxidative stress-induced cell death [14, 15]. Excessive apoptosis can lead to cardiomyocyte loss, myocardial damage and impaired cardiac function.

Pharmacological interventions for sodium arsenite-induced cardiotoxicity include

cardioprotective agents such as

Animal models and isolated cardiomyocytes serve as commonly employed models for exploring the toxic effects induced by pesticides, including cadmium, arsenic, atrazine, paraquat, etc. [21]. The widely used animal models provide valuable insights into the pathophysiology of pesticide-induced toxicity, such as sodium arsenite-induced cardiotoxicity and serve as platforms for testing novel cardioprotective agents [1, 2, 12]. Apart from these models, cell lines like H9c2 exhibiting many characteristics of cardiomyocytes are utilized to explore the protective efficacy of various compounds against pesticide-induced cardiotoxicity [22]. In-vitro investigations have demonstrated that arsenic elicits hypertrophic responses in adult H9c2 cells [22].

With the limited availability of effective treatments for pharmaceutical drugs

and their side effects, research focuses increasingly on understanding

etiopathological mechanisms and exploring traditional medicinal plant resources

with fewer side effects for alternative or complementary strategies [23, 24]. The

World Health Organization (WHO) also approximates that 3.5 to 4 billion

individuals worldwide continue to depend on pharmaceuticals sourced from

medicinal plants [25]. Fisetin, a plant flavonoid, exists in various fruits and

vegetables, such as strawberries, apples, onions and cucumbers [26]. It has a

wide range of potential health benefits and pharmacological effects, including

antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective in various neurodegenerative

diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease, anti-cancer,

anti-diabetic, anti-aging, anti-allergic, anti-asthmatic and bone repair [27, 28, 29].

Researchers documented the anti-cancer potential of fisetin via inhibition of

multiple signaling pathways involved in cancer progression, including protein

kinase B (PI3K or Akt), mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), nuclear factor

kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-

This study was conducted from January to March, 2024 at the Animal House of Qingdao Municipal Hospital, Qing Dao, China.

Male rats (strain: Sprague-Dawley, weight: 200–230 g) were procured from the

animal house of Qingdao Municipal Hospital. Rats were housed at normal

maintenance conditions, including temperature: 24

According to the previously reported method, sodium arsenite (Merck Ltd, Beijing, China; 5 mg/kg, p.o., 28 days) was administered in rats to induce cardiotoxicity [1]. The rats were randomly divided into various groups contain 15 rats in each group namely, arsenite control (As control, treated with 5 mL/kg, p.o. distilled water), coenzyme Q10 (Merck Ltd, Beijing, China; As+CoQ 10, treated with Coenzyme Q10 10 mg/kg, p.o.), fisetin (Merck Ltd, Beijing, China; F 5, F 10 and F 25 mg/kg, treated with fisetin 5, 10 or 25 mg/kg, p.o.) [26, 31] for 28 days. Another group of aged-matched healthy rats named as normal were also maintained and treated with distilled water (5 mL/kg, p.o.) for 28 days.

On the 29th day, electrocardiographic, hemodynamic changes and left ventricular contractile function were measured using an eight-channel recorder Power lab data acquisition system (AD Instruments Pvt. Ltd., with software LABCHART version 7.3 pro software, Bella Vista NSW, Australia) [2, 32].

Post behavioral assessment, the blood of anesthetized rats (ketamine (50 mg/kg; Pfizer Inc., New York City, NY, USA) and diazepam (5 mg/kg; Kern Liebers India, Tumkur, India), intramuscular) was collected using retro-orbital puncture. Serum was separated was used for the estimation of Creatine Kinase-MB (CK-MB), Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH), Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP), total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein, triglyceride and high-density lipoprotein using respective kits according to manufacturer’s instructions (Accurex Biomedical Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India) [33].

Then, animals were euthanized by carbon dioxide (3–7 liters/min flow for 10 L

chambers) asphyxiation, the heart was isolated to estimate the levels of total

protein, lipid peroxidation (Malondialdehyde (MDA) content), nitric oxide (NO

content), superoxide dismutase (SOD) and reduced Glutathione (GSH) as described

by Kandhare et al. [34] and Visnagri et al. [35]. The mRNA

expressions of Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2-Related Factor 2 (Nrf2,

NFE2L2, forward primer: CCTCACCTCTGCTGCCAGT, reverse primer:

GGGAGGAATTCTCCGGTCTC, base pair: 316), Heme Oxygenase 1 (HO-1,

HMOX1, forward primer: TTGTAACAGACTTGCCAGAG, reverse primer:

CACTCACTGGTTGTATGCG, base pair: 202), Bcl-2 Associated X (Bax, forward

primer: CTACAGGGTTTCATCCAG, reverse primer: CCAGTTCATCTCCAATTCG, base pair: 96),

B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2, forward primer: CGGAGGCTGGGATGCCTTTG, reverse

primer: TTTGGGGCAGGCATGTTGAC, base pair: 231) and Caspase-3 (CASP3,

forward primer: GCTGGACTGCGGTATTGAGA, reverse primer: TAACCGGGTGCGGTAGAGTA, base

pair: 108) were analyzed in cardiac tissue using using quantitative reverse

transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) as described by Visnagri

et al. [36] and Kandhare et al. [37]. Single-stranded cDNA was

synthesized from 5 mg total cellular RNA using a commercially available RT-PCR

kit (MP Biomedicals India Private Ltd., Mumbai, India). Amplification of

Data was expressed as a Mean

The body weight of normal rats and rats in the AS control and treatment groups

did not differ significantly. However, Table 1 illustrated the impact of sodium

arsenite on heart weight (absolute) and heart weight to body weight ratio

(relative heart weight). Compared to the normal group, administration of sodium

arsenite caused a significant increase (p

| Parameter | Normal | As control | As+CoQ (10) | As+F (5) | As+F (10) | As+F (25) |

| Body weight (gm) | 236.00 |

240.80 |

230.30 |

233.00 |

240.70 |

244.80 |

| Heart weight (gm) | 0.19 |

0.89 |

0.40 |

0.82 |

0.61 |

0.55 |

| Heart weight/body weight (×10-3) | 0.79 |

3.70 |

1.75 |

3.52 |

2.53 |

2.26 |

| Serum CK-MB (IU/L) | 1081 |

2474 |

1365 |

2486 |

1946 |

1527 |

| Serum LDH (IU/L) | 1375 |

2819 |

1754 |

2797 |

2465 |

2004 |

| Serum ALP (IU/L) | 123.50 |

349.60 |

151.50 |

329.30 |

277.00 |

196.30 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 13.72 |

54.52 |

19.59 |

49.31 |

35.54 |

27.22 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 60.16 |

159.90 |

73.71 |

146.40 |

120.70 |

97.53 |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | 1.06 |

7.01 |

1.46 |

6.34 |

4.05 |

2.42 |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 66.02 |

21.09 |

50.64 |

24.66 |

42.27 |

50.23 |

| VLDL-C (mg/dL) | 12.03 |

31.97 |

14.74 |

29.27 |

24.14 |

19.51 |

Data are expressed as Mean

Table 2 depicted a notable alteration in the cardiac parameters, encompassing

electrocardiography and hemodynamics, observed in rats following sodium arsenite

administration. The heart rate in AS control group showed a significant

(p

| Parameter | Normal | As control | As+CoQ (10) | As+F (5) | As+F (10) | As+F (25) |

| Heart rate (BPM) | 345.50 |

260.70 |

316.50 |

262.50 |

296.00 |

331.30 |

| QRS interval (ms) | 12.67 |

36.5 |

17.33 |

33.00 |

24.50 |

22.67 |

| QT interval (ms) | 48.00 |

89.33 |

56.00 |

87.67 |

78.00 |

59.00 |

| QTc interval (ms) | 131.50 |

185.50 |

141.20 |

175.70 |

165.30 |

147.70 |

| RR interval (ms) | 142.30 |

228.70 |

156.50 |

220.30 |

202.30 |

174.30 |

| PR interval (ms) | 14.00 |

31.17 |

15.67 |

30.00 |

24.67 |

21.50 |

| ST interval (ms) | 19.00 |

38.83 |

22.83 |

37.00 |

29.83 |

26.00 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 146.00 |

94.33 |

136.00 |

98.83 |

127.30 |

145.80 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 115.00 |

96.00 |

115.80 |

92.67 |

98.67 |

110.50 |

| MABP (mmHg) | 120.20 |

91.17 |

113.20 |

89.33 |

101.70 |

104.30 |

| LVEDP (mmHg) | 5.19 |

10.72 |

5.67 |

10.27 |

8.16 |

6.01 |

| LVESP (mmHg) | 86.54 |

128.40 |

85.95 |

132.00 |

116.40 |

97.07 |

| dp/dtMax | 3145 |

2534 |

3216 |

2636 |

3152 |

3222 |

| dp/dtMin | –827 |

–1343 |

–1057 |

–1283 |

–1084 |

–1046 |

| Systolic duration (ms) | 47.20 |

69.84 |

51.16 |

65.13 |

66.01 |

51.64 |

| Diastolic duration (ms) | 146.50 |

109.90 |

159.50 |

113.40 |

127.40 |

148.10 |

| Pressure time index | 16.35 |

28.95 |

19.61 |

28.49 |

26.61 |

18.59 |

| Contractility index | 58.01 |

40.25 |

60.96 |

41.83 |

47.83 |

58.93 |

| Tau (ms) | 4.80 |

9.04 |

5.19 |

8.59 |

5.54 |

4.57 |

Data are expressed as Mean

There was a significant decrease (p

There was a significant (p

The levels of CK-MB, LDH, ALP, total cholesterol, triglycerides, Low-Density

Lipoprotein (LDL)-C and Very Low-Density Lipoprotein (VLDL)-C increased

significantly (p

There was an effective reduction (p

| Parameter | Normal | As control | As+CoQ (10) | As+F (5) | As+F (10) | As+F (25) |

| SOD (U/mg of protein) | 9.25 |

4.42 |

8.08 |

4.73 |

6.31 |

7.80 |

| GSH (µg/mg protein) | 0.39 |

0.26 |

0.36 |

0.31 |

0.29 |

0.37 |

| MDA (nmol/L/mg of protein) | 2.32 |

7.16 |

2.93 |

7.01 |

5.24 |

3.36 |

| NO (µg/mL) | 6.52 |

15.39 |

6.74 |

13.31 |

12.38 |

9.76 |

| Total protein (mg/mL) | 20.83 |

62.64 |

30.94 |

54.37 |

45.60 |

39.01 |

Data are expressed as Mean

The levels of total protein, nitric oxide and MDA in cardiac tissue was markedly

elevated (p

The impact of fisetin on the alteration of cardiac Nrf2, HO-1, Bax, Bcl-2 and

Caspase-3 mRNA expressions induced by sodium arsenite is detailed in Fig. 1. The

significant down-regulation (p

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Effect of fisetin on sodium arsenite-induced alteration in

cardiac. (a) Nrf2, HO-1, Bax, Bcl-2 and Caspase-3 mRNA expression in rats, (b)

Quantitative representation of the mRNA expression of Nrf2, (c) HO-1, (d) Bax,

(e) Bcl-2, (f) Bax:Bcl-2 and (g) Caspase-3. Data are expressed as Mean

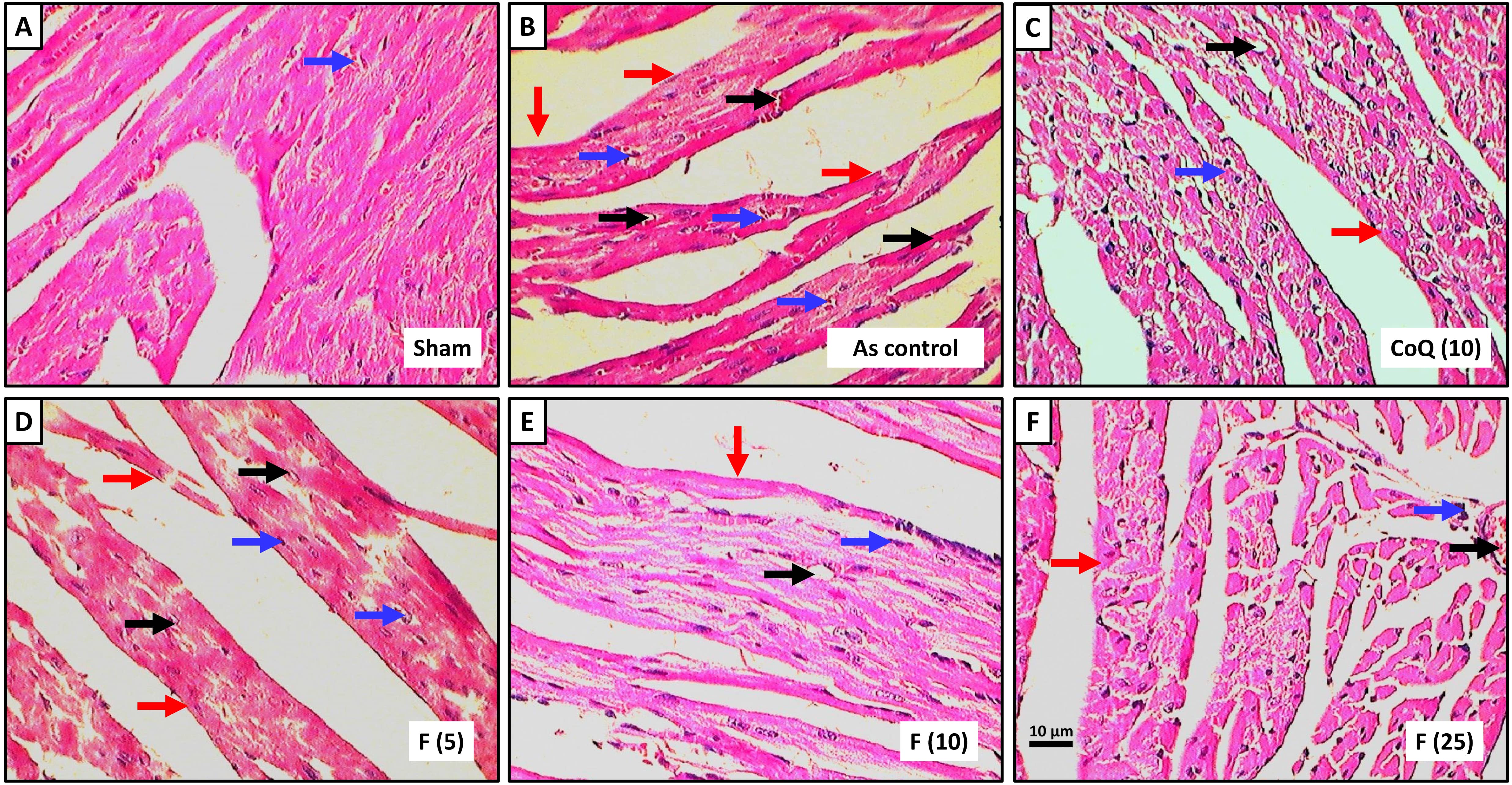

Fig. 2a depicted histopathological observations of the heart from the normal group, revealing a well-maintained architecture with normal myocardial fibers and muscle bundles, well-defined boundaries, mild congestion and inflammatory infiltration. The cardiac tissue from the AS control rats showed severe myocardial degeneration and necrosis (++++), congestion and vacuolization (+++), edema (++++) and infiltration of inflammatory cells (++++) with the disorganized arrangement of muscle bundles with no well-defined boundaries (Fig. 2b). Administration of CoQ showed protection against sodium arsenite-induced myocardial damage reflected by mild inflammatory infiltration (++), edema and congestion and myocardial necrosis (+) (Fig. 2c). Administration of fisetin (5 mg/kg) did not show any reduction in myocardial necrosis (++++), inflammatory infiltration (++++), congestion (+++) and edema (+++) when compared with AS control group (Fig. 2d). Cardiac tissue from fisetin (10 and 25 mg/kg) treated groups showed a reduction in myocardial aberrations induced by sodium arsenite reflected by the presence of moderate myocardial necrosis (+++ and ++), inflammatory cell infiltration (++ and +), congestion (++ and +) and edema (++ and +) (Fig. 2e,f) and (Table 4).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Effect of fisetin on sodium arsenite-induced alteration in heart

histology of rats stained with H&E staining. Photomicrograph of sections of the

heart of normal group, (a) Sodium arsenite control group, (b) Sodium

arsenite+Coenzyme Q10 (10 mg/kg), (c) Sodium arsenite+fisetin (5 mg/kg), (d)

Sodium arsenite+fisetin (10 mg/kg), (e) Sodium arsenite+fisetin (25 mg/kg) and

(f) Treated group. Images at 40

| Parameter | Normal | As control | As+CoQ (10) | As+F (5) | As+F (10) | As+F (25) |

| Myocardial necrosis | – | ++++ | + | ++++ | +++ | ++ |

| Congestion | + | +++ | + | +++ | ++ | + |

| Edema | – | ++++ | + | +++ | ++ | + |

| Vacuolization | – | +++ | + | +++ | ++ | – |

| Inflammatory infiltration | + | ++++ | ++ | ++++ | ++ | + |

As, Sodium arsenite control group; As+CoQ10 (10), Sodium arsenite+Coenzyme Q10 (10 mg/kg); As+F (5), Sodium arsenite+fisetin (5 mg/kg); As+F (10), Sodium arsenite+fisetin (10 mg/kg); As+F (25), Sodium arsenite+fisetin (25 mg/kg); –, No abnormality detected; +, Damage/active changes up to less than 25%; ++, Damage/active changes up to less than 50%; +++, Damage/active changes up to less 75%; ++++, Damage/active changes up to more than 75%.

In developed and developing countries, pesticides are widely used in agriculture, public health and household settings. However, chronic exposure to these pesticides through occupational, environmental or dietary routes can lead to long-term health effects, including cardiovascular complications [39]. Many pesticides, including sodium arsenite, induce oxidative stress, promote inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, etc., which are key mechanisms underlying the development of cardiotoxicity [1, 40]. Thus, this study investigated the potential of fisetin on sodium arsenite-induced cardiotoxicity via evaluating the expression of key genes involved in apoptosis, including Bax, Bcl-2 and Caspase-3, providing valuable insights into potential mechanisms of action.

Evaluating relative heart weight is essential for detecting cardiotoxicity, particularly in preclinical assessments. Changes in heart weight relative to body metrics offer insights into cardiac hypertrophy or atrophy, common in cardiotoxicity induced by drugs or toxins [41, 42]. While heart weight alone may not definitively diagnose cardiotoxicity, it improves understanding of cardiac pathology and identifies potential cardiotoxic agents when coupled with histological, biochemical and functional assessments [38]. Integrating heart weight evaluations into comprehensive protocols aids early detection and safety assessment of pharmaceuticals and environmental exposures [43, 44]. The substantial rise in heart weight and heart/body weight ratio in the arsenite control group corroborates prior findings on arsenic’s cardiotoxic effects [39]. The observed alteration in relative heart weight is a crucial indicator of arsenite-induced cardiotoxicity. Notably, rats treated with fisetin adverted these alterations, demonstrating its cardioprotective potential. Current study results aligned with the findings from previous investigators where fisetin exhibited its cardioprotective effects against cardiotoxicity induced by myocardial ischemia injury and doxorubicin via mitigating the elevation in heart weight and relative heart weight in rodents [45].

Furthermore, this organoprotective potential was further demonstrated by the favorable effects of fisetin on hemodynamic parameters, including systolic, diastolic and mean arterial blood pressure [46, 47]. Heart rate and blood pressure are the fundamental hemodynamic parameters, whereas stroke volume, cardiac output and total peripheral resistance are the advanced hemodynamic measures [48, 49, 50]. These improvements in blood pressure profiles indicate enhanced cardiac output and peripheral vascular function, possibly mediated by the vasodilatory and anti-inflammatory properties of fisetin [51]. The observed enhancements in the contractility index and pressure-time index further support the cardioprotective effects of fisetin against arsenite-induced myocardial dysfunction. Notably, the fisetin also positively affected tau [45], reflecting improved ventricular relaxation and diastolic function. The mechanisms underlying the cardioprotective effects are multifactorial and may involve antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and calcium-modulating properties [45, 52, 53, 54]. The alteration in electrocardiographic and hemodynamic parameters observed in this investigation offers valuable insights into fisetin’s cardioprotective potential against arsenite-induced cardiotoxicity.

Creatine Kinase MB (CK-MB) is an enzyme predominantly found in the myocardium and has elevated levels in the bloodstream, suggesting myocardial injury [55]. Researchers documented a link between sodium arsenite-induced cardiotoxicity and elevated CK-MB, reflecting myocardial injury and dysfunction [56, 57]. The LDH is another crucial intracellular enzyme in energy production that catalyzes pyruvate to lactate in anaerobic conditions [58, 59, 60]. Initially, LDH elevation indicates cardiac damage, diagnosing acute myocardial infarction and is also elevated in valve heart disease, heart failure and coronary artery disease [61, 62, 63]. Furthermore, changes in ALP levels observed during sodium arsenite-induced cardiotoxicity may be secondary to liver dysfunction, inflammation or other systemic effects [17]. In line with these studies, our results demonstrate a parallel pattern, where rats administered with arsenite displayed increased serum markers (CK-MB, LDH and ALP). However, treatment with fisetin prevented these changes, suggesting protection against arsenite-induced cardiac injury. The decrease in CK-MB and LDH levels following intervention with fisetin implies preserved cardiomyocyte integrity and reduced myocardial damage, which may be potentially attributed to the fisetin’s antioxidative properties, lipid peroxidation inhibition and prevention of membrane damage [26, 31]. Recent research reinforces the cardioprotective attributes of fisetin via averting the rise in CK-MB and LDH levels in rats experiencing myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury.

Many pesticides, including organophosphates, pyrethroids and organochlorines,

induce oxidative stress by generating ROS and disrupting antioxidant defense

mechanisms [26, 64, 65]. Oxidative stress in the cardiovascular system can lead to

lipid peroxidation, protein damage and DNA oxidation, contributing to endothelial

dysfunction, inflammation and atherosclerosis [66, 67, 68]. Consequently,

arsenite-induced cardiotoxicity is characterized by an imbalance in endogenous

antioxidant enzymes and oxidative stress markers. The levels of SOD and GSH were

reduced due to the excessive generation of arsenite-induced ROS [1] which further

alter the functions of proteins, lipids and DNA within the cardiac tissue. The

Nrf2 has been reported for its cellular defense potential against oxidative

stress [69, 70, 71, 72]. Overall, Nrf2 signaling plays a crucial role in protecting

against sodium arsenite-induced cardiotoxicity by orchestrating antioxidant,

anti-inflammatory and cytoprotective responses in cardiac cells. Numerous

researchers reported that antioxidant treatments such as ellagic acid, catechin,

eugenol, genistein, naringin, phloretin, resveratrol,

Nitric oxide (NO) is critical in regulating cardiomyocyte contractility, with inducible NO synthase implicated in cardiomyopathy and heart failure [74, 75]. Dysregulated NO synthesis contributes to arsenite-induced cardiotoxicity, as demonstrated in endothelial cell studies linking arsenite-induced redox activation with endothelial NO synthesis and apoptosis. The NO is also proposed as a marker of subclinical cardiac dysfunction in pediatrics. While physiologically acting as a vasodilator, elevated NO levels contribute to nitrosative stress and tissue damage [76, 77]. Current study findings depicted that fisetin modulated the NO levels, potentially by restoring NO homeostasis and reducing nitrosative stress in cardiac tissues of arsenite-induced rats. This was consistent with a study demonstrating that treatment with fisetin reduced the elevation of NO levels during myocardial ischemia injury and doxorubicin-induced myocardial damage in rodents [45, 52, 53, 54]. The cardioprotective effects of fisetin against arsenite-induced oxide-nitrosative stress may be attributed to hydroxyl groups in ring B that enhance the efficacy of flavonoids as potent free radical scavengers. Substituting phenolic hydroxyl groups onto this ring elucidates a mechanism involving hydrogen atom transfer or single-electron transfer, followed by sequential electron transfer-proton transfer, leading to significant antioxidant properties [78]. Fisetin, a flavonoid compound, features a B-ring arrangement with hydroxyl substitutions at C-3’ and C-4’ positions, which might contribute to its antioxidant potential.

Sodium arsenite-induced cardiotoxicity involves various mechanisms, one of which is apoptosis, a programmed cell death process that plays a significant role in cardiac injury and dysfunction [1, 2]. Arsenite exposure activates both intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathways in cardiac cells. The intrinsic pathway involves the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria and subsequent activation of caspase cascades, including Caspase-9 and Caspase-3, leading to apoptotic cell death [36, 79]. Furthermore, arsenite exposure downregulates anti-apoptotic pathways, such as Bcl-2 family proteins, which normally promote cell survival and inhibit apoptosis. Overall, apoptosis plays a significant role in sodium arsenite-induced cardiotoxicity by mediating cardiac cell death, impairing myocardial function and contributing to the development of cardiotoxicity [1, 2]. Thus, the researcher targeted apoptotic pathways as a potential therapeutic strategy for mitigating the adverse effects of arsenic exposure on the myocardium. Current results also demonstrated a reinstatement of Bcl-2 mRNA expression and a decline in Bax and Caspase-3 mRNA expression levels after fisetin treatment, culminating in a reduced Bax/Bcl-2 ratio. These observations suggest that fisetin confers cardioprotective effects by modulating apoptotic pathways, thereby alleviating arsenite-induced cardiotoxicity.

Histological analysis of cardiac tissue is vital in evaluating drug-induced cardiotoxicity and understanding the underlying mechanisms of heart pathology. It offers valuable insights into structural alterations within the myocardium, including myocardial degeneration, inflammation, fibrosis and vascular changes indicative of cardiac injury [11]. This analysis serves as a gold standard for assessing cardiotoxicity induced by chemotherapy agents like arsenic, enabling the detection of early signs of cardiac injury and guiding timely intervention to prevent irreversible damage [2]. Moreover, histopathological evaluation provides detailed morphological information, characterizing arsenite-induced cardiac lesions and elucidating their pathophysiological mechanisms. In current study, histological examination revealed significant myocardial degeneration, interstitial inflammation and myocardial cell hemorrhage in rats administered with arsenic, consistent with previous reports of arsenite-induced cardiotoxicity. However, administration of fisetin attenuated these histopathological alterations, indicating its potential cardioprotective effects against arsenite-induced cardiac damage. Current study findings aligned with prior research demonstrating the cardioprotective properties of fisetin against myocardial ischemia injury and doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity [45, 52, 53, 54].

The present study has several limitations. First, this study reported the cardioprotective potential of fisetin via its antioxidant and antiapoptotic potential however, future study is needed to explore another possible mechanism for the beneficial effects of fisetin against cardiotoxicity. Second, more comprehensive studies are needed to clarify the mechanism of fisetin using advanced techniques like echo-cardiography and TUNEL staining. Third, this study evaluated the effect of fisetin on a rat model, however, future studies focusing on isolated rat heart models using the Langendorff methods are needed to confirm the findings of the present study.

The findings of this study demonstrate that fisetin effectively mitigates sodium arsenite-induced cardiotoxicity in experimental rats. The protective effects of fisetin are associated with antioxidant (Nrf2/HO-1) and antiapoptotic pathway (Bax/Bcl-2 and Caspase-3) in experimental rats. Fisetin treatment dose-dependently attenuated cardiac dysfunction, reduced oxidative stress, and modulated key molecular markers involved in these pathways. These results suggest that fisetin may have potential as a therapeutic agent for preventing or treating arsenite-induced cardiotoxicity.

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

TZ conceived and designed the research study. LX performed the data acquisition and drafted the manuscript. TZ analyzed the data. Both (TZ and LX) authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. Both (TZ and LX) authors read and approved the final manuscript. Both (TZ and LX) authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The Animal Ethical Committee of Qingdao Municipal Hospital approved (approval no. 202188726D) all the experimental protocols. All procedures involving animals were conducted in accordance with the ARRIVE (Animal Research: Reporting of In-Vivo Experiments) guidelines and National Institute of Health Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Medical writing support for the development of this manuscript, under the direction of the authors, was provided by Yonnova Scientific Consultancy Pvt. Ltd. in accordance with the Good Publication Practice guidelines.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.