1 Department of Surgery, University of North Dakota School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Grand Forks, ND 58202, USA

2 Sanford Department of Cardiology, Sanford Health, Fargo, ND 58102, USA

Abstract

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) has become an established treatment for severe aortic stenosis, offering a minimally invasive alternative to surgical aortic valve replacement. Frequently, preoperative angiogram identifies coronary artery disease requiring percutaneous coronary intervention and thus dual antiplatelet therapy. While TAVR is associated with lower rates of bleeding and transfusion compared to surgical valve replacement, bleeding complications remain a concern. The impact of antiplatelet therapy on periprocedural bleeding, transfusion requirements, and long-term survival following TAVR remains uncertain.

A retrospective review was conducted on 1116 patients who underwent TAVR between 2012 and 2021. Bleeding severity and outcomes were classified using the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) criteria. Medication regimens, including preoperative antiplatelet therapy, were documented. Statistical analysis was performed using univariate, bivariate, and survival estimates to assess the impact of bleeding and transfusion on long-term outcomes.

A total of 248 patients were on dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT). Of these, 105 patients (9.4%) required a transfusion during hospitalization. Patients on preoperative ticagrelor DAPT were significantly more likely to require transfusions compared to clopidogrel DAPT, aspirin, and no antiplatelet therapy (26.3% vs. 12.8% and 7.9% and 9.2%; p = 0.01) compared to those on aspirin alone. Long-term survival was significantly worse in DAPT groups (p < 0.01). Female gender (p < 0.01), hyperlipidemia (p = 0.02), coronary artery disease (p < 0.01), and peripheral vascular disease (p < 0.01) were significantly more prevalent in patients receiving dual antiplatelet therapy compared to those on aspirin or no therapy.

Preoperative DAPT significantly increases the risk of periprocedural bleeding and transfusion, leading to decreased survival after TAVR. Severe bleeding independently predicts poorer survival outcomes. Consideration should be given to the timing of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and antiplatelet strategy prior to TAVR to optimize periprocedural safety. The impact of modifying preoperative antiplatelet strategies on medium and long-term clinical outcomes warrants further investigation.

Keywords

- dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT)

- transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR)

- aortic stenosis (AS)

Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement (TAVR) has revolutionized the treatment of aortic stenosis (AS), increasing the overall number of patients undergoing aortic valve replacement (AVR) and expanding access to those who may not be candidates for surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR). As TAVR adoption continues to grow, the number of SAVR procedures has decreased. Patients with concomitant coronary artery disease (CAD) and AS are common, and routine preoperative catheterization often reveals significant CAD. The management of concomitant CAD in TAVR patients remains controversial. The typical approach involves treating CAD with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and stenting, followed by TAVR [1]. This sequence frequently places patients on dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) after PCI and before TAVR, introducing challenges in balancing thrombotic and bleeding risks.

The optimal strategy for managing DAPT during TAVR is unclear [2, 3, 4]. Options include proceeding with TAVR while remaining on DAPT, temporarily stopping DAPT and bridging with another agent, or delaying TAVR. In practice, many centers perform TAVR while patients remain on DAPT, although there is a growing trend toward performing TAVR first, followed by PCI, depending on coronary anatomy and lesion characteristics [5, 6]. The clinical consequences of performing TAVR in patients on DAPT are not well defined. It remains uncertain whether DAPT increases bleeding or transfusion requirements and whether it affects short- or long-term outcomes. This study aimed to evaluate the impact of periprocedural DAPT on bleeding complications, transfusion needs, and clinical outcomes after TAVR, providing insight into optimal antiplatelet management in this patient population.

A retrospective cohort study was performed on patients who underwent TAVR between 2012 and 2021 at our institution (n = 1116). All patients who underwent TAVR during the study period were included, with no exclusion criteria applied. This reflects an all-comers population. All TAVRs were performed on an elective basis. No patients had active bleeding at the time of the procedure. Patient data, including baseline characteristics, antiplatelet therapy, and outcomes, were retrospectively reviewed. On average, the time between coronary angiography and TAVR was 71 days. DAPT was not routinely discontinued prior to TAVR.

Vascular access closure was achieved using Perclose ProGlide (Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, CA, USA) devices at the main valve insertion site. Postprocedural angiography was not routinely performed. Bleeding severity was classified according to the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) bleeding classification, outlined in the Valve Academic Research Consortium-3 (VARC-3) guidelines for standardizing TAVR outcomes [7]. Bleeding complications included both vascular access site complications and cardiac structural complications, consistent with VARC-3 definitions.

BARC criteria are divided into four types based on clinical severity and intervention requirements. Type 1 includes overt bleeding not necessitating surgical or percutaneous intervention but requiring medical care or hospitalization, and bleeding requiring a transfusion of 1 unit of blood. Type 2 includes bleeding necessitating transfusion of 2–4 units of blood. Type 3 refers to bleeding in critical organs, causing hypovolemic shock, severe hypotension, or requiring reoperation, with criteria such as transfusion of

Mean (SD) and median (IQR) values were computed for all continuous variables, and frequency distributions were calculated for all categorical variables. Demographic and other variable comparisons were performed using Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables and Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables. Kaplan-Meier survival estimates were calculated for patients with and without transfusion requirements and for those with dual antiplatelet therapy. Statistics were performed using Statistical Analysis System (SAS) (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA; Version 9.4 Users Guide). All statistical tests were two-tailed with p

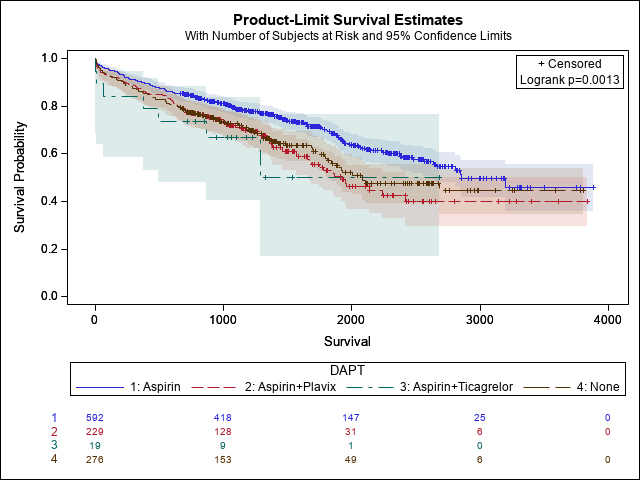

Packed red blood cell transfusion occurred in 9.4% (n = 105) of patients undergoing TAVR (Table 1). A total of 248 patients were on dual antiplatelet therapy, including 19 on ticagrelor DAPT and 229 on clopidogrel DAPT. An additional 276 patients were not receiving any antiplatelet therapy, while 592 patients were on aspirin monotherapy. Patients on preoperative clopidogrel and aspirin had significantly higher transfusion rates (12.8% vs. 7.9%; p= 0.01). Ticagrelor DAPT use similarly increased transfusion risk (26.3%; p = 0.01). Bleeding severity also differed significantly between groups (p = 0.01), with BARC 3 bleeding most common among ticagrelor DAPT patients (5.3%). Postoperative complications, including myocardial infarction, stroke or TIA, new pacemaker implantation, and atrial fibrillation, did not significantly differ between groups. Median hospital length of stay was similar across all cohorts. Patients receiving dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT), particularly with clopidogrel or ticagrelor, demonstrated reduced long-term survival following TAVR compared to those on aspirin monotherapy or no antiplatelet therapy. Survival curves began to separate after the first-year post-procedure (Fig. 1).

| Variables | Aspirin | Aspirin + Clopidogrel | Aspirin + Ticagrelor | None | p-value | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Total (N = 1116) | 592 (53.1) | 229 (20.5) | 19 (1.7) | 276 (24.7) | ||

| Received transfusion | 46 (7.9) | 29 (12.8) | 5 (26.3) | 25 (9.2) | 0.01 | |

| Bleeding classification by platelet regimen | 0.01 | |||||

| 0 | 553 | 200 | 14 | 251 | ||

| 1 | 27 | 20 | 3 | 18 | ||

| 2 | 8 | 7 | 1 | 3 | ||

| 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 4 | ||

| Post-operation MI | 121 (20.6) | 44 (19.4) | 4 (21.1) | 53 (19.2) | 0.96 | |

| Post-operation stroke/TIA | 71 (12.0) | 39 (17.0) | 1 (5.3) | 40 (14.5) | 0.28 | |

| Post-operation pacemaker | 90 (15.3) | 31 (13.6) | 2 (10.5) | 29 (10.5) | 0.28 | |

| Post-operation atrial fibrillation | 86 (14.6) | 34 (14.9) | 4 (21.1) | 40 (14.6) | 0.89 | |

| Hospital length of stay, median (range) | 2 (0–24) | 2 (1–107) | 2 (1–17) | 2 (0–38) | 0.52 | |

MI, myocardial infarction; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Kaplan-Meier survival curve comparing long-term survival following TAVR by preoperative antiplatelet regimen. TAVR, Transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

Baseline characteristics (Table 2) were generally well balanced across antiplatelet groups, with no significant differences in age, body mass index, STS score, or tobacco use. However, female gender was significantly more prevalent in patients receiving clopidogrel (63.3%) and ticagrelor (63.2%) DAPT compared to those on no antiplatelet therapy (47.1%; p

| Variables | Aspirin | Aspirin + Clopidogrel | Aspirin + Ticagrelor | None | p-value | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Total (n = 1116) | 592 (53.1) | 229 (20.5) | 19 (1.7) | 276 (24.7) | ||

| Age at procedure, median (range) | 79 (44–99) | 80 (53–98) | 78 (65–100) | 80 (50–98) | 0.19 | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 242 (40.9) | 84 (36.7) | 7 (36.8) | 146 (52.9) | ||

| Female | 350 (59.1) | 145 (63.3) | 12 (63.2) | 130 (47.1) | ||

| BMI, median (range) | 29.9 (17.0–57.4) | 29.0 (18.2–47.2) | 30.6 (21.0–44.3) | 29.3 (15.7–58.3) | 0.25 | |

| STS, median (range) | 3.5 (0.03–28.6) | 3.7 (0.6–24.2) | 3.2 (0.9–15.5) | 3.5 (0.8–25.8) | 0.18 | |

| Active Tobacco use | 37 (9.6) | 14 (9.0) | 1 (7.7) | 14 (8.5) | 0.98 | |

| Diabetes | 208 (18.8) | 79 (34.6) | 10 (52.6) | 83 (30.6) | 0.19 | |

| Chronic kidney disease | 152 (25.7) | 68 (29.7) | 7 (36.8) | 78 (28.3) | 0.49 | |

| Dialysis | 8 (1.4) | 7 (3.1) | 2 (10.5) | 10 (3.6) | 0.02 | |

| Hypertension | 508 (85.8) | 196 (85.6) | 18 (94.7) | 240 (87.3) | 0.66 | |

| Hyperlipidemia | 473 (79.9) | 189 (82.5) | 17 (89.5) | 201 (72.8) | 0.02 | |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 102 (17.2) | 43 (18.8) | 1 (5.3) | 47 (17.0) | 0.51 | |

| Coronary artery disease | 338 (65.5) | 210 (91.7) | 18 (94.7) | 132 (47.8) | ||

| Congestive heart failure | 207 (35.0) | 96 (41.9) | 7 (36.8) | 115 (41.7) | 0.15 | |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 54 (9.1) | 39 (17.0) | 3 (15.8) | 23 (8.3) | ||

BMI, body mass index; STS, society of thoracic surgeons.

Patients on clopidogrel or ticagrelor DAPT had significantly higher transfusion needs and more BARC-classified bleeding events. While aspirin alone did not increase bleeding compared to no antiplatelet therapy, dual therapy nearly doubled the transfusion rate. These findings support the hypothesis that preoperative DAPT increases periprocedural risk during TAVR.

Our findings underscore the complex interplay between antiplatelet therapy and bleeding complications in patients undergoing TAVR. We observed that patients on dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) had significantly higher transfusion rates, both clopidogrel and ticagrelor use were associated with increased bleeding risk. Notably, aspirin monotherapy was associated with lower transfusion rates compared to patients not on antiplatelet therapy, suggesting that aspirin monotherapy not only is safe but may also be more favorable in terms of bleeding risk.

Given the high prevalence of DAPT in patients undergoing PCI prior to TAVR, these results have important clinical implications. Our practice of performing PCI before TAVR necessitates careful reassessment, since PCI after TAVR would obviate the need for DAPT. For patients requiring PCI, bridging with intravenous antiplatelet agents during hospitalization could be explored to balance thrombotic and bleeding risks, although this approach would likely increase the length of stay and requires further investigation. Alternatively, recent studies suggest that shortened durations of DAPT may reduce bleeding risk without significantly increasing ischemic complications, particularly in patients with stable coronary disease [2].

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) plays a critical role in optimizing outcomes for patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR), particularly in the presence of significant coronary artery disease. PCI is generally recommended prior to TAVR when critical lesions are identified, especially in proximal coronary arteries where a large myocardial territory is at risk, as this can mitigate complications and enhance procedural success. Some studies suggest that performing PCI and TAVR simultaneously may reduce 30-day mortality compared to a staged approach, though this decision should be individualized [1, 2, 5]. Factors such as lesion complexity, clinical presentation, and anatomical characteristics are key considerations. For example, critical, high-risk lesions may warrant PCI before TAVR, while chronic, stable lesions with smooth contours might allow for TAVR first. Ultimately, balancing ischemic protection with bleeding risk is paramount, underscoring the importance of personalized, multidisciplinary decision-making.

Our data support a shift in practice toward minimizing or temporarily holding DAPT in the perioperative period for TAVR patients. For patients on clopidogrel or ticagrelor, transitioning to aspirin monotherapy may reduce bleeding complications without compromising short-term safety. Future prospective studies are essential to refine these strategies and establish evidence-based guidelines for managing antiplatelet therapy in TAVR patients, with the goal of optimizing both procedural safety and long-term survival outcomes. These findings may help inform evolving clinical guidelines by supporting more individualized approaches to antiplatelet therapy based on bleeding risk, coronary anatomy, and PCI timing.

The primary strengths of this study are its large retrospective cohort, which significantly enhances statistical power to detect meaningful differences, and the extended study period (2012–2021), which allows for a comprehensive long-term survival analysis. The use of standardized bleeding definitions, as outlined by the BARC/VARC-3 criteria, ensures consistency in clinical assessments and facilitates comparability with existing literature. Moreover, the detailed stratification of antiplatelet regimens (aspirin monotherapy versus DAPT with clopidogrel or ticagrelor) provides valuable insights into their respective impacts on periprocedural transfusion requirements.

This study has several limitations. Its retrospective, single-center design limits causal inference and generalizability. Although the study included a large all-comers cohort with no exclusions, this may have introduced heterogeneity that could not be fully adjusted for in the analysis. In addition, antiplatelet regimens were not randomized, introducing potential selection bias, nor did we evaluate baseline bleeding risk factors such as a history of bleeding disorders or liver dysfunction. The lack of more granular stratification by CAD severity and PCI indication limits our ability to determine whether the observed associations with DAPT are independently attributable to the antiplatelet therapy itself or are instead reflective underlying disease complexity.

Preoperative DAPT therapy, particularly with clopidogrel or ticagrelor, significantly increases the risk of periprocedural bleeding and transfusion. Consideration should be given to the timing of percutaneous coronary intervention prior to TAVR and modifying antiplatelet strategies to reduce perioperative bleeding risk without compromising procedural success. These findings may influence clinical decision-making regarding the necessity of perioperative PCI and optimal periprocedural medication management in TAVR candidates.

The data supporting the findings of this study are owned by Sanford Health and are not publicly available. However, they can be accessed upon reasonable request to the corresponding author, with permission from the institution.

HR: drafting article, concept/design, data collection. AM: concept/design, data collection, drafting article. GS: drafting, concept/design, data collection. JT: drafting, concept/design, data collection. AS: drafting, statistics, data analysis/interpretation. TH: supervision, drafting, concept/design, critical revision. CD: project administration, concept/design, drafting article, critical revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

This retrospective chart review study involving human participants was in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The Human Investigation Committee (IRB) of Sanford Health Fargo approved this study (ID: MOD00011199). This study was reviewed by the Institutional Review Board, which determined that patient consent was not required due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Not applicable.

Support for study obtained through the Sanford Surgical Research Fellowship from Sanford Health, and the Research Experience for Medical Students (REMS) program through the University of North Dakota School of Medicine and Health Sciences.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Portions of the grammar, phrasing, and verbiage in this manuscript were refined with the assistance of OpenAI’s ChatGPT. No content or original ideas were generated by ChatGPT; its use was limited to language polishing and editorial support under the direct supervision of the authors.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.