1 Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, First Hospital of Lanzhou University, 730000 Lanzhou, Gansu, China

2 The First Clinical Medical College of Lanzhou University, 730000 Lanzhou, Gansu, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Cryoballoon ablation (CBA) and laser balloon ablation (LBA) are important techniques for treating atrial fibrillation (AF). However, the differences in their effectiveness remain unclear. This study aimed to systematically evaluate and compare the efficacy of CBA and LBA in AF treatment.

A comprehensive search of major databases, including PubMed, Cochrane Library, Embase, and Web of Science, was conducted up to July 2024 to identify clinical studies comparing CBA and LBA for treating AF. Odds ratios (ORs) were calculated using a fixed-effect model. Study differences, quality, and potential publication bias were also assessed.

A total of 16 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) involving 4437 patients were included in the meta-analysis. The meta-analysis showed that compared to LBA, CBA was associated with a higher risk of phrenic nerve paralysis (PNP) (OR: 1.81, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.23–2.67, p = 0.003, I2 = 0.0%). However, CBA demonstrated a higher success rate of pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) (OR: 2.14, 95% CI: 1.18–3.88, p = 0.013, I2 = 11.2%) and a shorter surgery duration standardized mean difference (SMD): –0.58, 95% CI: –0.88 to –0.29, p = 0.000, I2 = 75.3%). No significant differences were found between CBA and LBA regarding stroke, cardiac tamponade, hematoma, or 12-month AF recurrence rates.

Compared to LBA, CBA offers a higher success rate of PVI and shorter surgery durations but with an increased risk of PNP.

INPLASY202480069, https://inplasy.com/inplasy-2024-8-0069/, last accessed on August 14, 2024.

Keywords

- cryoballoon ablation

- laser balloon ablation

- atrial fibrillation

- systematic review

- meta-analysis

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the disorganization of the heart’s electrical activity, characterized by irregular flutter waves that disrupt normal contraction and relaxation. AF is the most common type of rapid heart rhythm disorder observed in clinical practice, with a prevalence in the general population of 1.5–2% [1]. The incidence of AF increases with age, reaching about 2.3% in individuals over 40 and 5.9% in those over 65 [2]. According to the Framingham study [3], AF significantly elevates mortality risk by 1.5 to 1.9 times compared to individuals without AF. Additionally, AF reduces the survival advantage typically seen in women in terms of average lifespan. Patients with AF face an elevated risk of serious complications, including thromboembolism, heart failure, and stroke [4]. Among cardiovascular conditions, AF has a particularly profound impact on stroke incidence, increasing the risk by five times more than in those without AF. This risk further escalates with age [5]. The pathophysiological mechanisms of AF involve four main factors: (1) ion channel dysfunction, (2) abnormal calcium ion flow, (3) atrial structural remodeling, such as fibrosis or chamber dilation, and (4) autonomic nervous system dysregulation. These factors contribute to cardiac muscle cell ectopic discharges and re-entry mechanisms [6]. Several risk factors, including hypertension, heart failure, obesity, smoking, and diabetes [6, 7], can trigger these pathophysiological processes, leading to the development of AF.

Guidelines for managing AF [8, 9] suggest considering ablation procedures based on pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) when antiarrhythmic drug therapy is insufficient. For patients with AF that is difficult to manage with medication, physicians may recommend ablation procedures based on PVI. Common methods include radiofrequency ablation, pulse field ablation, and balloon-based techniques such as cryoballoon ablation (CBA), hot balloon ablation (HBA), and laser balloon ablation (LBA). Compared to the traditional and widely used radiofrequency ablation, CBA offers several advantages, including a shorter learning curve, ease of use, enhanced safety, and more predictable patient treatment outcomes [10]. As a result, its use is becoming increasingly widespread. CBA uses liquid nitrogen to cool and destroy the heart tissue responsible for abnormal electrical activity, thereby eliminating AF [11, 12]. LBA, a recent innovation, employs laser energy to deliver precise energy for more durable PVI [13] and includes an endoscope for enhanced balloon positioning and visual guidance [14, 15]. However, complications such as phrenic nerve paralysis (PNP), which may arise with these advanced balloon ablation techniques, should not be overlooked. Numerous studies have compared the overall effectiveness of CBA and LBA in treating AF, yet their conclusions are often inconsistent or supported by insufficient evidence. Therefore, this study aimed to systematically evaluate and compare these two technologies through a meta-analysis to clarify their clinical feasibility and safety. The findings will provide more comprehensive decision support for clinical management.

This study followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [16]. The comprehensive research protocol is officially registered with INPLASY under the number INPLASY202480069. Details are available at https://inplasy.com/inplasy-2024-8-0069/, last accessed on August 14, 2024.

A literature search was conducted in PubMed, the Cochrane Library, Web of Science, and Embase databases to examine the differences in treatment effectiveness between CBA and LBA for AF. The search covered the inception of these databases until July 2024 and included additional documents from other scholarly sources. The method involved a combination of predefined keywords and free-text searches. Search terms included atrial fibrillation, fibrillation, atrial, fibrillations, atrial, auricular fibrillation, fibrillation, auricular, cryoablation, cryoballoon ablation, laser balloon ablation, and laser balloon.

Two researchers collaborated to select studies for inclusion. Initially, the researchers used EndNote 21 software (Clarivate, Philadelphia, PA, USA) to remove duplicates and screened titles and abstracts under the initial eligibility criteria. Subsequently, the researchers obtained and reviewed the full texts of studies that potentially met the inclusion criteria and cross-checked their findings. In disagreements between researchers, a third party determined whether to include the study. The inclusion criteria for the meta-analysis were as follows: (1) Studies must be randomized controlled trials (RCTs); (2) studies must compare CBA with LBA for the first time in patients with AF and provide clinical outcome reports; (3) study subjects must meet the diagnostic criteria outlined in the 2023 ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS Atrial Fibrillation Diagnosis and Management Guidelines [17]. The exclusion criteria included: (1) low relevance to the topic; (2) duplicate studies; (3) studies lacking complete or valid data; (4) reviews, letters, conference abstracts, and other types of documents; (5) non-English studies.

Our primary study outcomes were PNP and surgery duration. Secondary outcomes included stroke, the 12-month AF recurrence rates, cardiac tamponade, hematoma, and the success rate of PVI.

We utilized a standardized data extraction form that included the following: (1) Basic information and baseline characteristics of the study population, such as the first author and year, type of study, sample size, gender, and age. (2) Past medical history, including a history of heart failure, hypertension, diabetes, and coronary artery disease. (3) Pre-surgery tests and surgical details, including left atrial diameter and left ventricular ejection fraction. (4) Outcome measures included PNP, surgery duration, stroke, the 12-month AF recurrence rates, cardiac tamponade, hematoma, and the success rate of PVI, as well as any procedures performed to treat irregular heartbeats.

Since all the studies included in this analysis were RCTs, quality was assessed by two reviewers using Cochrane’s Risk of Bias tool, version 1.0 software (Cochrane Collaboration Oxford, England, UK). The reviewers evaluated the studies based on seven key areas: the generation of random sequences, concealment of assignment, blinding of patients and trial staff to treatment allocation, blinding of outcome assessors, handling of incomplete data, reporting bias, and additional biases. Furthermore, the GRADE approach (a systematic method for grading the quality of evidence) was applied to classify the quality of evidence for each outcome. This assessment considered the risk of bias, imprecision, inconsistency, indirectness, and publication bias, ultimately resulting in an overall quality rating for the evidence.

Traditional meta-analysis methods used Stata 18.0 software (Stata Corp LLC, College Station, TX, USA) to generate forest plots, sensitivity analysis plots, and Egger’s test plots. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated for categorical variables, while standardized mean difference (SMD) was used for continuous variables. The study heterogeneity was primarily assessed using the I2 statistic. An I2 value greater than 50% or a p-value less than 0.05 indicated significant heterogeneity. In such cases, a random-effects model was employed for the meta-analysis. If no significant heterogeneity was revealed, a fixed-effects model was applied. Funnel plots were used for qualitative assessment, and Egger’s test was used for the quantitative evaluation of publication bias, assessing the symmetry of the funnel plot and determining whether the p-value for Egger’s test exceeded 0.05.

A total of 225 papers were initially identified, with an additional three papers obtained from other sources. After digitally removing duplicate studies, 173 papers remained for initial screening based on titles and abstracts. Subsequently, a more detailed preliminary screening was conducted. The full texts of 24 papers were thoroughly examined to assess their eligibility for inclusion in the analysis. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 16 papers [1, 10, 15, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30] met the standards and were selected for the meta-analysis. The details of this selection are illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Flow diagram of the literature search and selection process. RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Table 1 (Ref. [1, 10, 15, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30]) summarizes the basic characteristics of the study populations included in the literature. The study involved 4437 patients, averaging 61.2 years (ranging from 58 to 76 years), and 62.4% (ranging from 55% to 84%) were male. Seven reports provided CHA2DS2-VASc scores, a measure to predict stroke risk in patients with AF. The average CHA2DS2-VASc score was 2.0. Among these patients, hypertension was present in 59.7% (ranging from 37.5% to 85.7%), 12.7% (ranging from 4.6% to 23.3%) had diabetes, 12.8% (ranging from 1.8% to 56.4%) had heart failure, and 18.9% (ranging from 5.7% to 45.7%) had coronary heart disease.

| Study | General characteristics | CHA2DS2-VASc Score | Past medical history (%) | Echocardiographic parameters | Group | |||||||||||

| Country | Study type | Total | Male (%) | Age (Y) | BMI | HTN (%) | Stroke (%) | HF (%) | DM (%) | CAD | LA, mm | LVEF (%) | CB | LB | ||

| Kobori et al. 2021 [21] | Japan | RCT | 100 | 62/76 | 68.8/65.2 | NR | NR | 52.0/42.0 | NR | 6.0/2.0 | NR | NR | 36.5/35.5 | 62.4/62.5 | CB2 | LB1 |

| Stöckigt et al. 2016 [1] | German | RCT | 70 | 77/77 | 64.2/66.2 | 29.1/27.9 | 2.5/2.7 | 71.4/85.7 | 5.7/0 | NR | 20.0/17.1 | 40.0/45.7 | NR | 53.6 /56.8 | CB2 | LB1 |

| Chun et al. 2021 [10] | US | RCT | 200 | 58/54 | 65.0/66.5 | 28.3/28.0 | 2.0/2.3 | 65.0/68.0 | 2.0/4.0 | 1.0/2.0 | 12.0/9.0 | 12.0/21.0 | 39.1/39.8 | 61.5/61.5 | CB2 | LB1 and LB2 |

| Dietrich et al. 2023 [19] | US | RCT | 69 | 55/55 | 65/67 | NR | NR | 62.5/79.3 | 5.0/13.8 | 27.5/24.1 | 10.0/17.2 | 30.0/24.1 | NR | NR | CB3 | LB3 |

| Seki et al. 2022 [25] | Japan | RCT | 100 | 68/74 | 66/66 | 24/25 | 2/2 | 48.0/50.0 | 8.0/2.0 | NR | 6.0/12.0 | 12.0/16.0 | 40/38 | 58/58 | CB4 | LB1 |

| Bordignon et al. 2013 [18] | German | RCT | 140 | 70/61 | 63/63 | NR | NR | 62.9/60.0 | NR | NR | 10.0/14.3 | 5.7/12.9 | 39.8/39.9 | 63/63 | CB1 | LB1 |

| Tohoku et al. 2020 [26] | German | RCT | 2433 | 56/57 | 66/66 | 28.0/28.6 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 40.0/40.6 | NR | CB3 | LB2 and LB3 |

| Tsyganov et al. 2015 [28] | Czech Republic | RCT | 100 | 66/60 | 62.2/62.8 | NR | NR | 60.0/68.0 | NR | NR | 12.0/20.0 | NR | 42.4/43.5 | NR | CB2 | LB1 |

| Khan et al. 2023 [20] | US | RCT | 558 | 70/82 | 65/66 | NR | NR | 72.2/72.7 | 7.6/4.8 | 36.6/56.4 | 19.0/23.3 | 19.3/22.9 | NR | NR | CB3 | LB1 |

| Schiavone et al. 2022 [24] | Italy | RCT | 110 | 69/67 | 62.9/63.4 | 25.8 /26.7 | 2/2 | 67.3/70.0 | 10.9/14.6 | 7.3/1.8 | 7.3/9.1 | 12.7/9.1 | NR | 61.7/60.3 | CB2 | LB2 and LB3 |

| Ohkura et al. 2023 [22] | Japan | RCT | 65 | 79/72 | 66.5/67.9 | 24.0/23.9 | NR | 36.4/59.4 | 0/3.1 | 15.2/3.1 | 12.1/21.9 | NR | 36.7/38.9 | NR | CB2 | LB1 |

| Tokuda et al. 2023 [27] | Japan | RCT | 245 | 76/84 | 61.7/61.2 | 24.6/24.2 | 1/1 | 47.7/40.2 | NR | NR | 10.4/5.4 | NR | 38.0/37.0 | 64.8/65.2 | CB4 | LB1 and LB3 |

| Wissner et al. 2014 [29] | German | RCT | 64 | 70/66 | 61/63 | NR | 1.9/2.0 | 70.0/68.2 | 10.0/9.1 | NR | 5.0/4.6 | 15.0/6.8 | 41/43 | 64/64 | CB1 | LB1 |

| Yano et al. 2021 [30] | Japan | RCT | 111 | 58/57 | 76/70 | 22.7/23.7 | 3/2 | 56.4/60.7 | 10.9/8.9 | 9.1/5.4 | 9.1/19.6 | NR | 43/42 | 70/70 | CB2 | LB1 |

| Kumar et al. 2014 [15] | Holland | RCT | 60 | 73/75 | 58/58.9 | 28/29 | NR | 37.5/40.0 | NR | NR | NR | 17.5/20.0 | NR | 58/57 | CB2 | LB1 |

| Reddy et al. 2008 [23] | Czech Republic | RCT | 12 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Total | / | / | 4437 | 61.0/64.5 | 64.8/64.9 | 23.5/23.7 | 1.8/1.7 | 57.8/61.7 | 6.8/6.1 | 22.6/26.0 | 13.3/15.4 | 17.4/19.8 | 39.6/39.8 | 61.7/61.8 | / | / |

HTN, hypertension; HF, heart failure; BMI, body mass index; CAD, coronary artery disease; LA, left atrial diameter; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; DM, diabetes mellitus; RCT, randomized controlled trial; NR, not reported.

This study includes research published between 2008 and 2023, encompassing 16 papers that discuss the first to fourth generations of CB and the first to third generations of LB. The second-generation CB (Arctic Front Advance, Medtronic Inc.) and the first-generation LB (HeartLight, CardioFocus) were the most commonly used in these studies.

We evaluated the studies in our review using the Cochrane quality assessment tool. As illustrated in Fig. 2a,b, all 16 studies were rated high quality. In the GRADE assessment of evidence quality, three outcomes were rated as high, three as moderate, and one as low. Table 2 presents the detailed GRADE evidence quality assessments.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Included study bias risk assessment results. (a) Bar chart of the risk of bias. (b) Risk of bias summary chart.

| Certainty assessment | Certainty | |||||||

| Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication bias | |||

| PNP | ||||||||

| 14 | RCT | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Undetected | 4296 | High |

| Surgery Duration | ||||||||

| 9 | RCT | serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Undetected | 824 | Moderate |

| Stroke | ||||||||

| 4 | RCT | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Very serious | Undetected | 505 | Low |

| Cardiac Tamponade | ||||||||

| 5 | RCT | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Undetected | 521 | High |

| Hematoma | ||||||||

| 5 | RCT | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | serious | Undetected | 937 | Moderate |

| Success Rate of PVI | ||||||||

| 7 | RCT | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Undetected | 804 | High |

| 12-month AF Recurrence Rates | ||||||||

| 6 | RCT | Not serious | Not serious | serious | Not serious | Undetected | 622 | Moderate |

PNP, phrenic nerve paralysis; PVI, pulmonary vein isolation; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Fourteen studies [1, 10, 15, 18, 20, 21, 22, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30] investigated PNP. These studies showed no significant differences, as indicated by an I2 of 0.0%. Therefore, a fixed-effect model, which assumes a single true effect size across studies, was used for the meta-analysis. These results indicated a significantly higher rate of PNP in the CBA group compared to the LBA group (OR: 1.81, 95% CI: 1.23–2.67, p = 0.003; I2 = 0.0%). See Fig. 3 for more details.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Forest plots for PNP. OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; PNP, phrenic nerve paralysis.

Nine studies [1, 15, 18, 19, 21, 24, 28, 29, 30] provided results on surgical duration. Due to significant heterogeneity among the studies (I2 = 75.3%), a random-effects model was applied for the meta-analysis. This statistical method combines the results of multiple studies while accounting for variability between them. The results showed that the CBA group had a shorter surgery duration than the LBA group (SMD: –0.58, 95% CI: –0.88 to –0.29, p = 0.000; I2 = 75.3%). See Table 3 for further details.

| Outcomes | Studies | Patients | OR/SMD | 95% CI | p-value | I2 (%) |

| Twelve-month AF recurrence rates | 6 | 622 | 1.21 | 0.83–1.76 | 0.312 | 30.7 |

| Success rate of PVI | 7 | 804 | 2.14 | 1.18–3.88 | 0.013 | 11.2 |

| Cardiac tamponade | 5 | 521 | 0.83 | 0.25–2.76 | 0.765 | 0.0 |

| Hematoma | 5 | 937 | 1.31 | 0.55–3.12 | 0.545 | 0.0 |

| LB1 | 2 | 200 | 0.70 | 0.09–5.52 | 0.732 | 0.0 |

| LB2 or LB3 | 2 | 179 | 1.26 | 0.20–8.02 | 0.804 | 14.9 |

| Stroke | 4 | 505 | 0.32 | 0.05–2.08 | 0.235 | 0.0 |

| Surgery duration | 9 | 824 | –0.58 | –0.88 to –0.29 | 75.3 | |

| LB1 | 7 | 645 | –32.34 | –50.49 to –14.19 | 87.7 | |

| LB2 or LB3 | 2 | 179 | –16.30 | –27.42 to –5.17 | 0.004 | 0.0 |

OR, odds ratio; SMD, standard mean difference; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; PNP, phrenic nerve paralysis; PVI, pulmonary vein isolation; LB, laser balloon.

The analysis included four studies [10, 18, 22, 25] that reported stroke outcomes. Since there was no significant difference between the studies (I2 = 0.0%), a fixed-effects model was applied for the meta-analysis. The results indicate no significant difference in stroke incidence between the CBA and LBA groups (OR: 0.32, 95% CI: 0.05–2.08, p-value: 0.235; I2 = 0.0%), as shown in Table 3.

Five studies [1, 18, 21, 25, 30] reported outcomes on cardiac tamponade. The meta-analysis used a fixed-effect model with an I2 of 0.0%, indicating consistent study findings. The results showed no statistically significant difference in the occurrence of cardiac tamponade between the CBA and LBA groups (OR: 0.83, 95% CI: 0.25–2.76, p = 0.765; I2 = 0.0%). Refer to Table 3 for detailed results.

Five studies [15, 18, 19, 20, 24] reported on hematomas, which are pools of blood outside the blood vessels. Researchers used a fixed effect model due to an I2 of 0.0% for the meta-analysis, a statistical method that combines the results of multiple studies. This analysis showed no meaningful difference between the CBA and LBA groups. The OR was 1.31 (OR:1.31, 95% CI: 0.55–3.12, p = 0.545; I2 = 0.0%). See Table 3 for more details.

Seven studies [1, 10, 15, 18, 21, 28, 29] reported on the success rate of PVI. Given the low heterogeneity among these studies (I2 = 11.2%), a fixed effect model was used for the combined analysis (meta-analysis). The analysis showed that the PVI success rate in the CBA group was significantly higher than in the LBA group (OR: 2.14, 95% CI: 1.18–3.88).

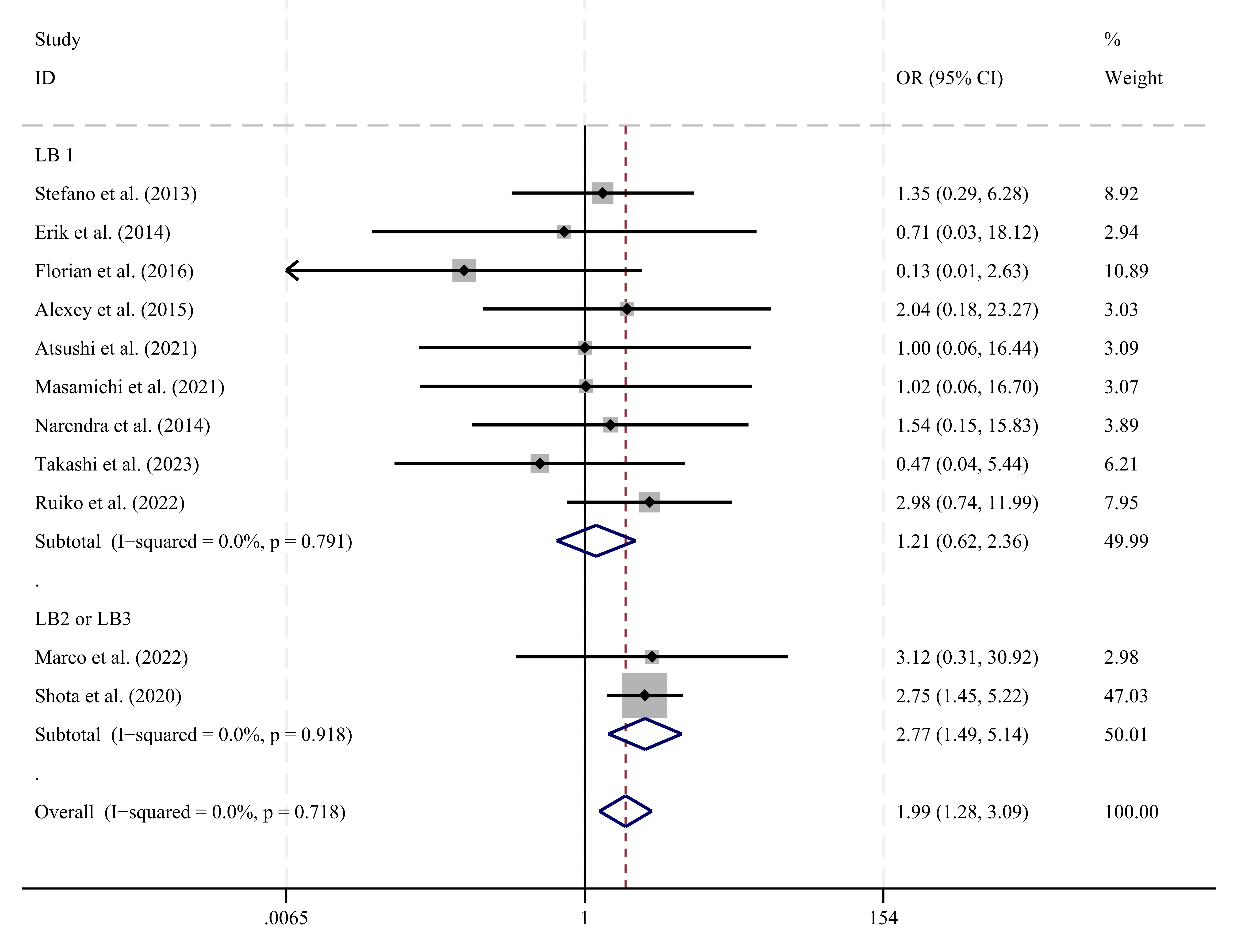

Six studies [1, 10, 18, 21, 23, 28] reported on the 12-month AF recurrence rates. Given the low heterogeneity among the studies (I2 = 30.7%), a fixed-effect model was employed for the meta-analysis. The results showed no statistically significant difference between the CBA and LBA groups (OR: 1.21, 95% CI: 0.83–1.76, p = 0.312; I2 = 30.7%). See Table 3 for further details.

Due to significant heterogeneity in some of the outcome measures, we aimed to identify the sources of this variation. We used the CB and LB subgroup categories as the basis for our analysis, conducting analyses sequentially for each outcome measure. Figs. 4,5 show the main outcomes for CB1 to CB4 and LB1 to LB3, respectively. The study of the other secondary outcomes is presented in Table 3.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Forest plot of the subgroup analysis of PNP in groups CB1–4. OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; PNP, phrenic nerve paralysis; CB, cryoballoon.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. Forest plot of the subgroup analysis of PNP in groups LB1–LB3. OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; PNP, phrenic nerve paralysis; LB, laser balloon.

In group CB1 (Arctic Front, Medtronic Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA), which included two studies [18, 29], no significant difference was found between the CBA and LBA groups (OR: 1.19, 95% CI: 0.30–4.68, p = 0.800; I2 = 0.0%). Similarly, Group CB2, which included eight studies [1, 10, 15, 21, 22, 24, 28, 30], found no significant difference between the CBA and LBA groups (OR: 1.37, 95% CI: 0.66–2.86, p = 0.395; I2 = 0.0%). Group CB3 (Arctic Front Advance-Short Tip Medtronic Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA), which comprised two studies [20, 26], found a significant difference, with a higher likelihood of developing peripheral neuropathy (PNP) (OR: 2.20, 95% CI: 1.25–3.87, p = 0.007; I2 = 80.5%). In Group CB4 (Arctic Front Advance Pro, Medtronic Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA), which also included two studies [25, 27], no significant difference was found between the CBA and LBA groups (OR: 1.94, 95% CI: 0.73–5.19, p = 0.186; I2 = 0.0%).

In the LB1 group, which included nine studies [1, 15, 18, 21, 22, 25, 28, 29, 30], no significant difference was found between the CBA and LBA groups (OR: 1.21, 95% CI: 0.62–2.36, p = 0.570; I2 = 0.0%). For the LB2 (HeartLight Excalibur Balloon; CardioFocus, Marlborough, MA, USA) and LB3 (HeartLight X3; CardioFocus, Marlborough, MA, USA) groups, which included two studies [24, 26], the analysis showed a significant difference, indicating a higher probability of developing peripheral neuropathy (PNP) in the CBA group compared to the LBA group (OR: 2.77, 95% CI: 1.49–5.14, p = 0.001; I2 = 0.0%).

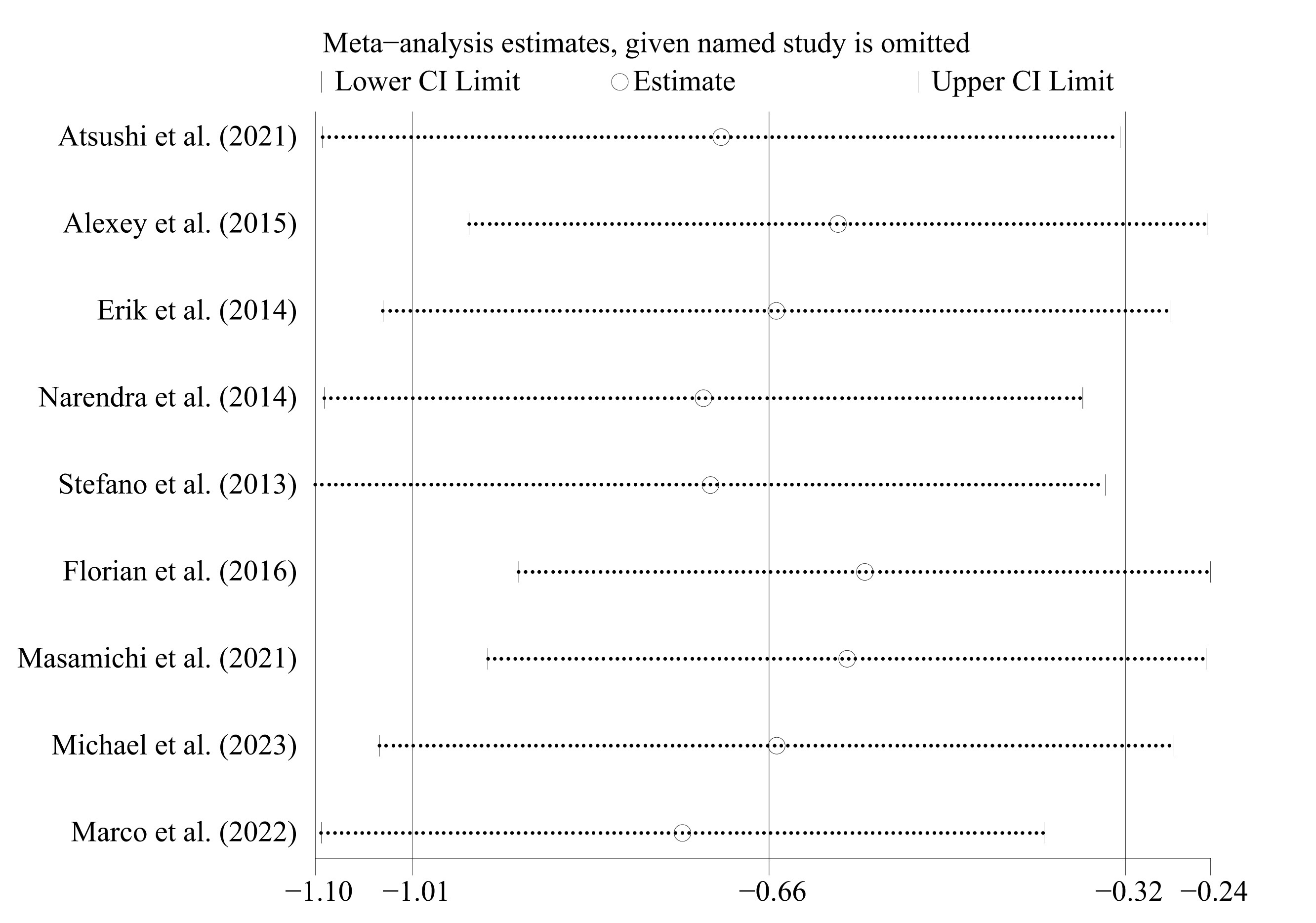

We performed a sensitivity analysis specifically for outcomes with high heterogeneity. Even after removing each study one at a time, the results remained consistent, indicating a high level of stability in our findings. Fig. 6 illustrates one of these outcomes: surgery duration.

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6. Sensitivity analysis of surgery duration. CI, confidence interval.

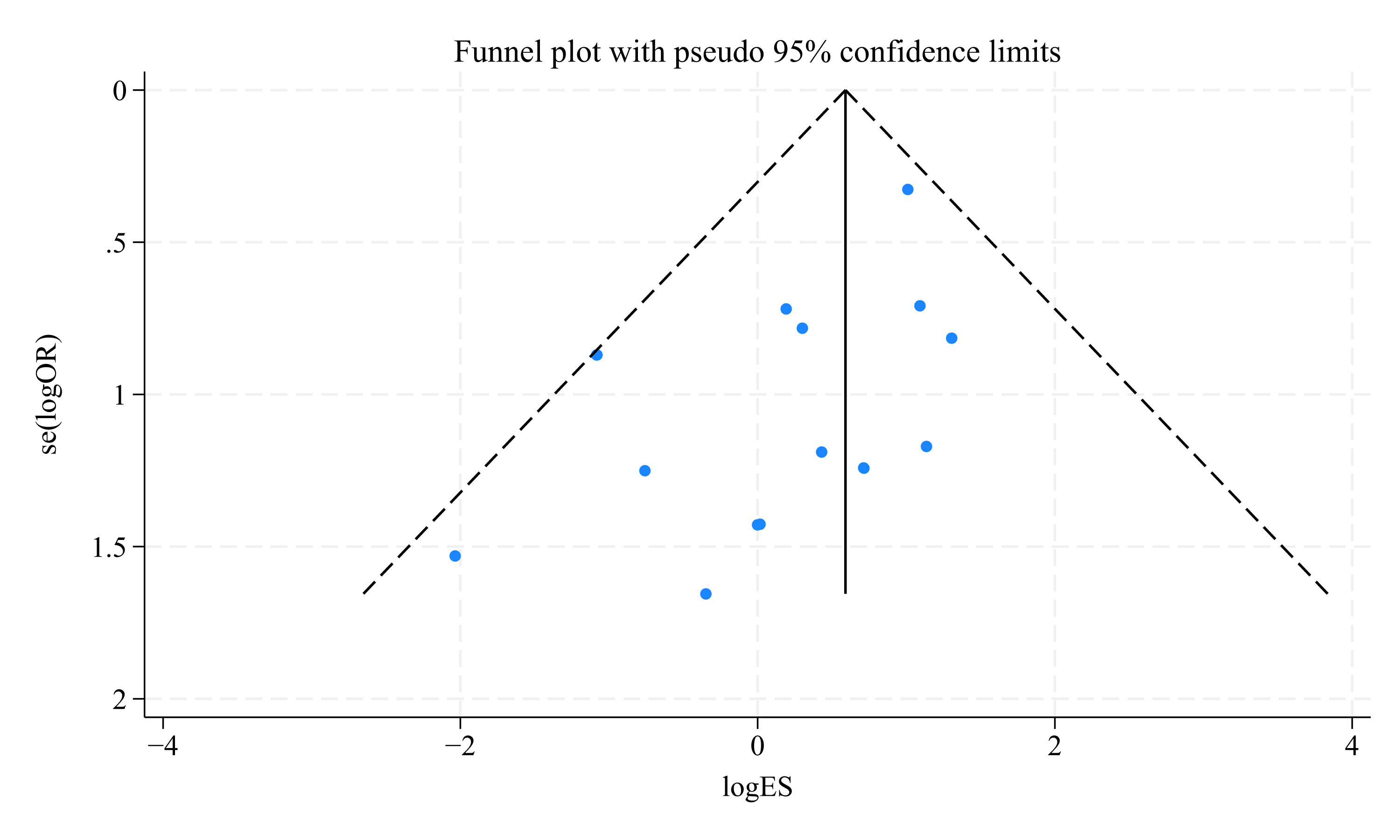

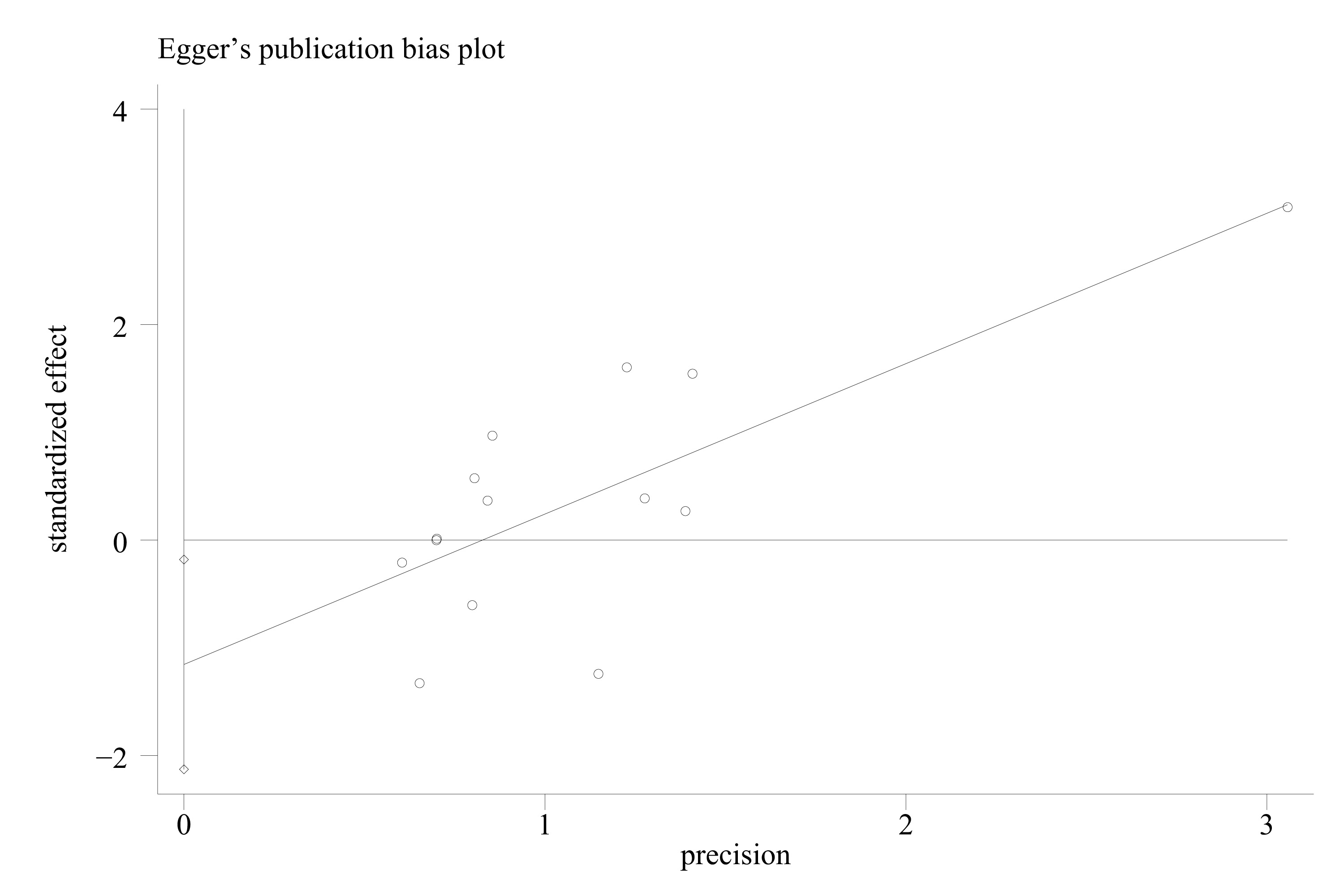

We assessed publication bias using Stata18.0 software, generating funnel plots (graphs commonly used to detect bias in systematic reviews or meta-analyses) for all outcomes. The plots for the studies are mostly symmetrical, suggesting no evident reporting bias. For instance, the plot for PNP is illustrated in Fig. 7 in the appendix. To further assess publication bias, we used Egger’s test and found the following results: PNP (p = 0.064), surgery duration (p = 0.173), stroke (p = 0.078), 12-month AF recurrence rates (p = 0.719), hematoma (p = 0.492), success rate of PVI (p = 0.462), and cardiac tamponade (p = 0.571). Since all p-values are above 0.05, the publications exhibited no significant bias. These results suggest that the findings are statistically reliable and unbiased. The Egger’s test for PNP is shown in Fig. 8.

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7. Funnel plot for PNP. OR, odds ratio; ES, effect size; PNP, phrenic nerve paralysis.

Fig. 8.

Fig. 8. Egger’s test for PNP. PNP, phrenic nerve paralysis.

This report analyzes 16 studies involving 4437 patients focused on evaluating the practicality, safety, and feasibility of CBA and LBA in clinical applications. The main findings are as follows: (1) CBA shows a higher success rate for complete PVI during surgery than LBA; (2) PNP is the most common complication, with a higher incidence in the CBA group than in the LBA group. No significant differences were found between CBA and LBA in stroke, cardiac tamponade, or hematoma; (3) CBA significantly reduces surgery duration compared to LBA; (4) according to the 12-month follow-up results, there was no significant difference in the AF recurrence rate between the two groups.

In 2015, a study by Alexey et al. [28] found no significant difference in the success rate of PVI with a single balloon between CBA and LBA (OR = 1.47, p = 0.83). However, in 2016, Florian et al. [1] found that CBA had a significantly higher success rate in achieving PVI than LBA (OR = 15.58, p = 0.003). Regarding postoperative complications, Masamichi et al. [30] conducted a study in 2021 that showed no significant difference in the likelihood of developing PNP between CBA and LBA (OR = 1.02, p = 0.990). Conversely, a 2022 study by Ruiko et al. [25] revealed a significantly higher probability of developing PNP with CBA compared to LBA (OR = 2.98, p

This meta-analysis showed no significant differences in outcomes such as stroke, cardiac arrest, and hematoma, with both CBA and radiofrequency ablation (RFA) exhibiting similar and low incidence rates, indicating minimal impact on patients’ coagulation functions.

Furthermore, the 12-month AF recurrence rates were comparable between the two groups, suggesting similar medium-term efficacy for CBA and RFA. However, significant differences were observed in PNP, surgery duration, and success rate of PVI, aligning with the findings of previous studies [1, 10, 21, 25, 26, 28, 29, 30].

The likelihood of PNP is significantly higher with CBA than LBA, consistent with the findings from studies [10, 25, 26]. Several factors contribute to this difference: (1) During the procedure, controlled energy is intentionally applied only to the target vein [28]. (2) CBA does not permit real-time monitoring of diaphragmatic movement during catheter advancement, which can cause the balloon to come dangerously close to the diaphragm [26], potentially affecting phrenic nerve (PN) conduction. In contrast, LBA facilitates diaphragmatic movement monitoring by palpation during PN pacing [31, 32, 33], enabling timely adjustments to the ablation site and preventing rapid cooling of the PN due to its concentrated energy delivery [14], thus maintaining normal function [34]. (3) Additionally, the cooling cycles utilized in CBA also play a role in influencing this phenomenon [35, 36]. (4) Studies have reported the incidence of PNP to range from approximately 3.5% to 25%, but this can be substantially reduced in some institutions, likely due to operator experience and balloon size (such as 28 mm CBA) [28]. Fortunately, PNP is typically transient, with most patients experiencing a recovery of PN function within three to six months [10, 25], and long-term complications are rare.

We found that the surgery duration for CBA is significantly shorter than that for LBA, consistent with the findings [1, 19, 28, 29, 30]. This might be attributed to the following reasons: (1) LBA requires more controlled environmental conditions, and if there is incomplete contact in areas where the esophagus temperature increases, the balloon must be repositioned to avoid blind spot ablation [10], leading to longer surgical times. (2) CBA often performs single-time pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) [37, 38], while the highly compliant balloon used in LBA allows adjusting to different sizes, enabling precise, point-by-point lesion ablation, which extends surgery duration [10]. Additionally, the LB3 now includes an integrated motor unit [39], and its “RAPID” mode may expedite energy delivery, potentially reducing the surgery durations. In our study, the duration of the surgery demonstrates significant variability attributable to, as suggested by our subgroup analyses and clinical experiences, the varying generations of instruments used in LBA and CBA and variations in surgeon expertise.

In terms of the success rate of PVI, CBA demonstrates significantly higher success than LBAs, consistent with findings [1, 29]. Several factors contribute to these differences: (1) Research indicates that when using lasers to transfer energy, the esophagus temperature rises too quickly and excessively, often leading to premature termination of energy delivery, particularly in LIPV [40]; (2) PVI failure is also closely related to the design of ablation tools. Studies have shown that the first-generation LB sheath offers limited controllability and steerability, affecting the balloon’s stable connection to the PV and complicating the operations [1]; (3) the occurrence of PNP can also lead to ablation interruption [18]. In addition, it is noteworthy that the current diagnostic tools for AF remain very limited and cannot enable early diagnosis of AF. Standardized perioperative management for AF patients is also an aspect that deserves attention.

This meta-analysis includes 16 studies with 4437 research subjects but has several limitations: First, this analysis only encompasses English-language studies, which might introduce selection bias. Second, due to insufficient data, this study does not consider certain complications, such as pulmonary vein stenosis (PVS) [27, 41] or silent cerebral events [42]. Additionally, most studies have a follow-up period of around 12 months, which limits our understanding of long-term health outcomes. Moreover, the recurrence of asymptomatic AF might be overlooked due to the limited use of continuous heart monitoring techniques, such as regular ECG and Holter-ECG, potentially affecting the long-term efficacy assessments of treatments, including CBA and LBA.

CBA and LBA are both effective and safe methods for radiofrequency ablation surgeries. Compared to LBA, CBA significantly reduces surgery durations and enhances the success rate of PVI, although it is associated with a higher risk of PNP. Therefore, we recommend CBA as the preferred treatment option for patients with AF; however, it is crucial to rigorously monitor for developing PNP complications intraoperatively or postoperatively. Fortunately, complications arising from both techniques typically resolve over time. We sincerely hope that more treatment methods for AF will emerge to improve patient prognosis.

The original data has been uploaded as an attachment to the manuscript.

ZA, ZW, and BS were responsible for topic selection and research design. SJ and YC conducted the literature search, paper screening, and data extraction. GL, XL, and HL performed the statistical analysis. SJ, YC, and GL wrote the manuscript. HL, ZA, and ZW proofread the manuscript. XL and BS reviewed and revised the paper. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the project.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Gansu Province (24JRRA305).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/HSF47013.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.