1 Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, State Key Laboratory of Frigid Zone Cardiovascular Disease, General Hospital of Northern Theater Command, 110016 Shenyang, Liaoning, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Lower antegrade body perfusion (LABP) can shorten the duration of hypothermic circulatory arrest. However, the efficacy of LABP combined with mild hypothermic circulatory arrest (MiHCA) remains unclear. This randomized controlled trial investigated whether applying LABP during total arch replacement (TAR) improves clinical outcomes compared to moderate hypothermic circulatory arrest (MoHCA).

Adult patients undergoing first-time TAR were randomly assigned to the MiHCA group (n = 147, MiHCA + LABP) or the MoHCA group (n = 147). Primary outcomes included the incidence of temporary neurological dysfunction (TND), permanent neurological deficit (PND), acute kidney injury (AKI), and serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels.

The baseline characteristics were comparable between the groups. No significant differences were observed in the incidence of TND or PND. However, the MiHCA group had a significantly shorter circulatory arrest time (5 vs. 16 minutes; p < 0.001), lower incidence of AKI (29.9% vs. 41.5%; p = 0.039), and lower ALT levels at 24 hours postoperatively (39.3 vs. 48.0 U/L; p = 0.012).

MiHCA combined with LABP appears to be a safe and feasible strategy in total arch replacement for acute type A aortic dissection. The addition of LABP significantly reduces the time of circulatory arrest, which may contribute to lower rates of AKI and improved hepatic function postoperatively.

ChiCTR2000033852, https://www.chictr.org.cn/hvshowproject.html?id=38552&v=1.1.

Keywords

- aortic dissection

- total arch replacement

- lower body perfusion

- mild hypothermic circulatory arrest

Acute type A aortic dissection (ATAAD) is the most fatal form of aortic dissection, associated with high morbidity and mortality rates [1, 2]. In China, total arch replacement (TAR) combined with frozen elephant trunk (FET) implantation has become a widely adopted strategy for treating ATAAD. This approach integrates the advantages of open surgery and endovascular repair, offering favorable outcomes with relatively low morbidity and mortality [3, 4]. Moreover, the use of a single upper hemisternotomy (UHS) has enabled the adoption of minimally invasive techniques in this complex procedure [5].

Previous research has indicated that rewarming from moderate to deep hypothermia may contribute to neurological injury, while mild hypothermia is associated with a lower risk of rewarming-related neurocomplications [6]. Lower antegrade body perfusion (LABP) during aortic arch surgery significantly reduces circulatory arrest time and distal organ ischemia, allowing for higher operative temperatures and improved organ protection [7]. Based on this evidence, we introduced mild hypothermic circulatory arrest (MiHCA) combined with LABP into the management of ATAAD [8]. Despite the promise of this combination, most existing studies on LABP are retrospective and focus on its application under moderate or deep hypothermic conditions. Thus, a lack of prospective data remains to evaluate LABP combined with MiHCA, while the impact of this strategy on major organ outcomes has not been well characterized.

To further investigate the protective effects of MiHCA versus moderate hypothermic circulatory arrest (MoHCA) on major organs, specifically the brain, liver, and kidneys, we conducted a single-center, prospective, non-inferiority trial to assess the safety and efficacy of MiHCA combined with LABP during TAR for ATAAD.

This was a single-center, randomized, prospective, non-inferiority clinical trial conducted at the General Hospital of Northern Theater Command, Shenyang, China. The study followed the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the hospital’s Ethics Committee (Approval No. K2020.19). The study was registered with the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR2000033852) before patient enrollment. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before randomization. The manuscript adheres to the CONSORT reporting guidelines.

Eligible participants were adults aged 18 to 80 years scheduled for total aortic arch replacement with FET implantation between July 2020 and August 2022. Exclusion criteria included: (1) history of two or more prior cardiac surgeries; (2) cardiac surgery combined with procedures on other organs; (3) liver or kidney dysfunction (defined as laboratory values exceeding three times the upper limit of normal); (4) concurrent conditions requiring radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or long-term corticosteroid therapy; (5) participation in other clinical trials.

Participants were randomized into either the MI group (MiHCA + LABP) or the MO group (MoHCA) using a computer-generated randomization sequence with concealed allocation. Patients, clinical staff, and outcome assessors were blinded to group assignments.

All procedures were performed via a single upper hemisternotomy, with an incision extending from the sternal notch to the fourth intercostal space and laterally into the right fourth intercostal space. Cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) was established by cannulation of the innominate artery and right atrium. Meanwhile, the right subclavian or carotid artery was used in cases where the innominate artery was unsuitable for use. Cardioplegia was administered through cannulation of the aortic root or coronary ostia. The right superior pulmonary vein was cannulated for left ventricular venting.

In the MO group, circulatory arrest was initiated when nasopharyngeal temperature reached 25–28 °C, in line with prior protocols [5]. Bilateral selective antegrade cerebral perfusion (BSACP) was administered via the arterial line, and a 15 Fr cannula was inserted into the left or right common carotid artery. After clamping the brachiocephalic arteries, circulatory arrest was initiated. A stent graft (MicroPort Medical Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) was deployed into the true lumen of the descending aorta using the FET technique. The stent graft was anastomosed to the distal end of a 4-branch prosthetic graft, and lower body perfusion was reinitiated through the graft.

In the MI group, MiHCA was initiated at 28–31 °C. A 16 Fr balloon catheter (Longlaifu, Changzhou, Jiangsu Province, China) was inserted via the 4-branch prosthetic graft (VASCUTEK Ltd., a Terumo Company, Inchinnan, Scotland) to occlude the distal aorta and allow for controlled LABP. After the distal anastomosis with the stent graft was completed, LABP was switched to the 4-branch graft for continued perfusion (Video. 1).

Application of mild hypothermic circulatory arrest combined with lower antegrade body perfusion during total arch replacement. The video demonstrates the following surgical steps: (1) upper hemisternotomy; (2) cannulation of the left carotid artery and right atrium for CPB; (3) delivery of antegrade cardioplegia via the coronary ostia; (4) implantation of the stent graft (frozen elephant trunk); (5) placement of a 16 Fr occlusion balloon cannula for lower antegrade body perfusion; (6) anastomosis of the 4-branch prosthetic graft to the stent graft; (7) anastomosis of the innominate artery to the prosthetic graft; (8) placement of a chest drainage tube. Abbreviations: CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass. Video associated with this article can be found in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/HSF46894.

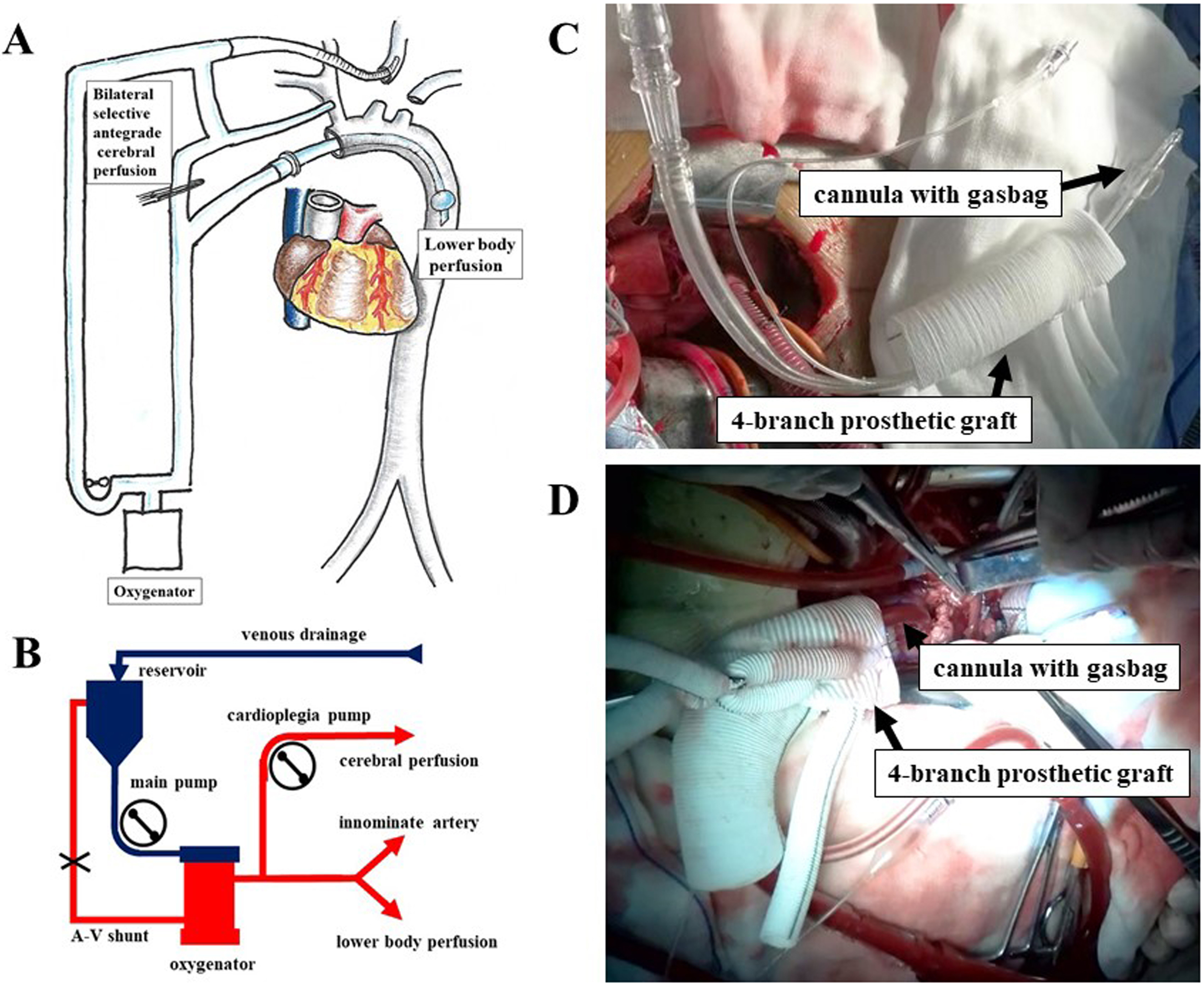

Subsequent steps were identical between groups, including anastomoses to the left common carotid artery, the proximal aortic stump, the left subclavian artery, and the innominate artery, followed by CPB rewarming, placement of temporary pacing wires, and pericardial drainage. Regional cerebral oxygen saturation (rSO2) was continuously monitored using the INVOS 5100 system to adjust the BSACP flow as needed (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Application of LABP and SACP during total arch replacement. (A) BSACP and LABP were managed using separate pumps: LABP was controlled by the main pump, while an auxiliary cardioplegia pump regulated SACP. (B) Transition between systemic perfusion, SACP, and LABP. At the start of surgery, systemic perfusion was established via the innominate artery using the main pump. During circulatory arrest (CA), the main pump line was clamped, an arteriovenous (AV) shunt was opened, and SACP was delivered to the innominate and left common carotid arteries via the cardioplegia pump. After CA, LABP was resumed using the main pump, while SACP continued via the cardioplegia pump. (C) Placement of a balloon occlusion cannula through the 4-branch prosthetic graft. (D) LABP was administered through the balloon occlusion cannula. Abbreviations: LABP, lower antegrade body perfusion; SACP, selective antegrade cerebral perfusion; BSACP, bilateral selective antegrade cerebral perfusion; CA, circulatory arrest; AV, arteriovenous.

Temporary neurological dysfunction (TND) was defined as transient motor deficits, confusion, or delirium that fully resolved before hospital discharge. Permanent neurological deficit (PND) refers to stroke or coma confirmed by brain CT with persistent neurological impairment. Acute kidney injury (AKI) was classified according to the RIFLE criteria [8]. Perioperative blood transfusion was defined as the administration of red blood cells, plasma, or platelets during either the intraoperative or postoperative period. Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels were measured preoperatively and at 24 hours postoperatively, along with other clinical parameters.

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous variables with normal distribution are expressed as the mean

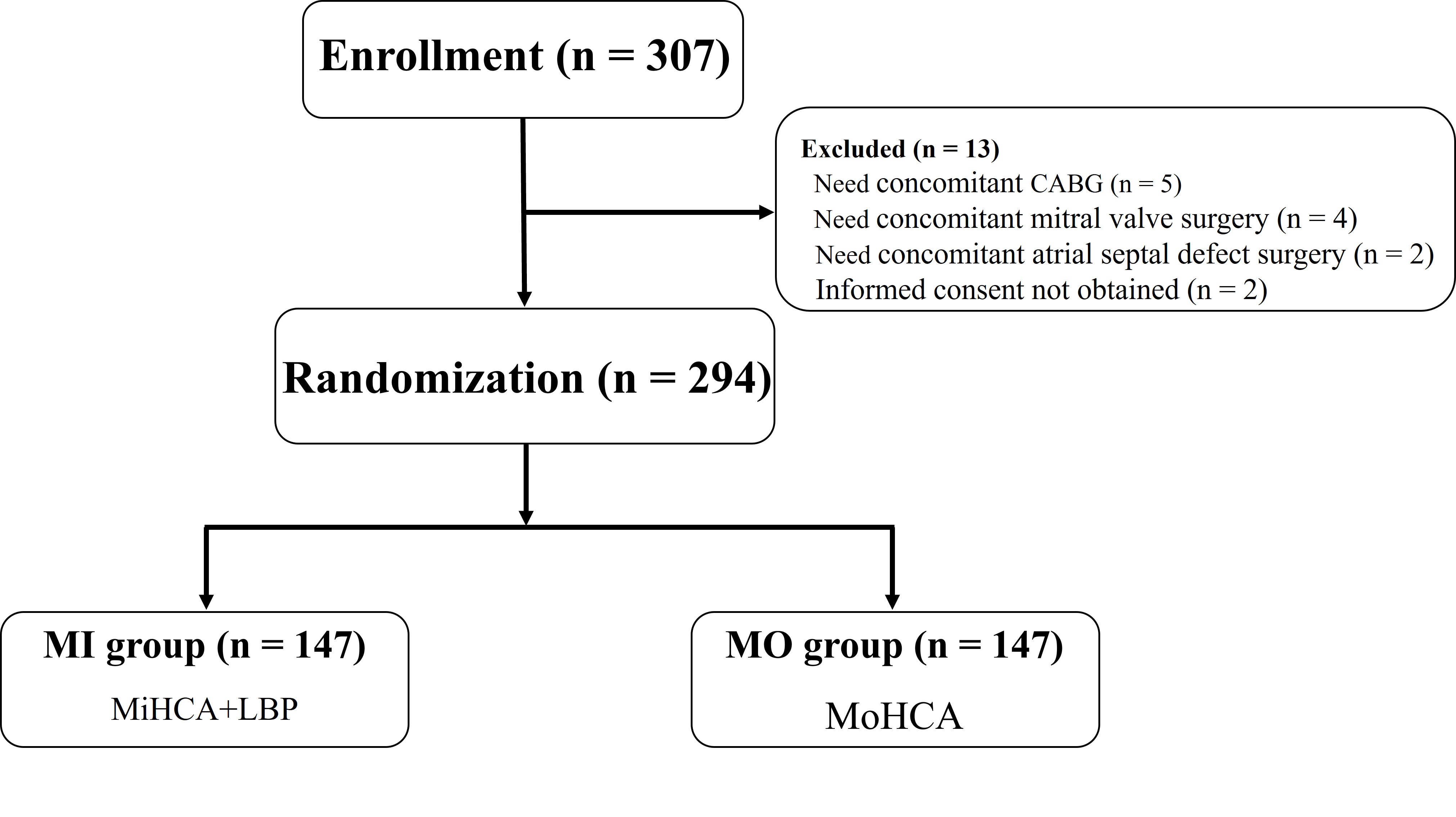

Between July 2020 and August 2022, 307 patients were assessed for eligibility at the General Hospital of Northern Theater Command due to acute type A aortic dissection (ATAAD). A total of 294 patients provided informed consent and were randomized equally into the MI group (n = 147) and the MO group (n = 147) (Fig. 2). Baseline clinical characteristics were comparable between the two groups (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Patient enrollment flowchart. A total of 307 patients with acute type A aortic dissection (ATAAD) were referred to the General Hospital of Northern Theater Command. Of these, 294 provided informed consent and were randomized equally into the MI group (n = 147) and the MO group (n = 147). Abbreviations: ATAAD, acute type A aortic dissection; MI, mild hypothermic circulatory arrest with lower antegrade body perfusion; MO, moderate hypothermic circulatory arrest.

| Variable | MI group (n = 147) | MO group (n = 147) | p-value |

| Age (years) | 54.0 (44.0, 60.0) | 53 (46.0, 58.0) | 0.829* |

| Male (%) | 111 (75.5) | 106 (72.1) | 0.507† |

| Weight (kg) | 77.0 (65.0, 88.0) | 75.0 (66.0, 88.0) | 0.849* |

| LVEF (%) | 58.0 (57.0, 60.0) | 58.0 (57.0, 59.0) | 0.797* |

| Smoking (%) | 80 (54.4) | 76 (51.7) | 0.640† |

| Diabetes (%) | 2 (1.4) | 5 (3.4) | 0.251‡ |

| Hypertension (%) | 111 (75.5) | 102 (69.4) | 0.240† |

| Marfan’s syndrome (%) | 13 (8.8) | 9 (6.1) | 0.375‡ |

| Pre-ALT (U/L) | 24.8 (16.0, 41.5) | 29.8 (18.0, 48.1) | 0.082* |

| Pre-Cr (µmol/L) | 66.4 (57.6, 92.8) | 68.0 (58.0, 89.1) | 0.673* |

LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; Pre-ALT, pre-operative alanine aminotransferase; Pre-Cr, pre-operative creatinine.

*Mann–Whitney U test; †Chi-squared test; ‡Fisher’s exact probability test.

The primary outcomes of this study were defined as the occurrence of organ dysfunction, including TND, PND, AKI, acute renal failure, and paraplegia. There was no statistically significant difference in the overall incidence of organ dysfunction between the MiHCA (MI) group and the MoHCA (MO) group (54.4% vs. 64.6%, p = 0.096).

However, the incidence of AKI was significantly lower in the MI group (29.9%) compared to the MO group (41.5%; p = 0.039). Although the incidence of acute renal failure was also lower in the MI group, the difference did not reach statistical significance.

No significant differences were observed between the two groups in the incidence of TND (10.9% vs. 7.5%; p = 0.313), PND (4.1% vs. 3.4%; p = 0.759), or paraplegia (1.4% vs. 2.0%; p = 0.652) (Table 2).

| Variable | MI group (n = 147) | MO group (n = 147) | p-value | |

| Ventilation time (h) | 28 (19, 64) | 22 (18, 47) | 0.094* | |

| ICU stay (h) | 44 (39, 89) | 43 (22, 89) | 0.252* | |

| First 24 h chest tube drainage (mL) | 250 (170, 350) | 290 (190, 460) | 0.048* | |

| Perioperative blood transfusion | 91 (61.9) | 98 (66.7) | 0.394† | |

| Reoperation for bleeding (%) | 2 (1.4) | 0 | 0.156‡ | |

| Reventilation (%) | 4 (2.7) | 3 (2.0) | 0.702‡ | |

| 24 h post-ALT (U/L) | 39.3 (29.6, 58.3) | 48.0 (32.4, 80.3) | 0.012* | |

| Postoperative length of stay (d) | 15 (11, 21) | 14 (11, 19) | 0.487* | |

| In-hospital death (%) | 12 (8.2) | 10 (6.9) | 0.658† | |

| Organ dysfunction (%) | 80 (54.4) | 95 (64.6) | 0.096† | |

| TND (%) | 16 (10.9) | 11 (7.5) | 0.313† | |

| PND (%) | 6 (4.1) | 5 (3.4) | 0.759‡ | |

| AKI (%) | 44 (29.9) | 61 (41.5) | 0.039† | |

| Acute renal failure (%) | 12 (8.2) | 15 (10.2) | 0.545‡ | |

| Paraplegia (%) | 2 (1.4) | 3 (2.0) | 0.652‡ | |

ICU, intensive care unit; TND, transient neurological dysfunction; PND, permanent neurological dysfunction; 24 h post-ALT, 24 h postoperative alanine aminotransferase; 24 h post-Cr, 24 h postoperative creatinine.

*Mann–Whitney U test; †Chi-squared test; ‡Fisher’s exact probability test.

The MI group had a significantly shorter circulatory arrest time compared to the MO group (5 vs. 16 minutes; p

Other secondary outcomes, including CPB time, aortic cross-clamp time, BSACP time, mechanical ventilation time, intensive care unit (ICU) length of stay, incidence of paraplegia, and in-hospital mortality, did not differ significantly between the two groups (Tables 2,3).

| Variable | MI group (n = 147) | MO group (n = 147) | p-value | |

| Bentall procedure (%) | 20 (13.6) | 16 (10.9) | 0.477† | |

| David procedure (%) | 1 (0.7) | 2 (1.4) | 0.562‡ | |

| Aortic valvuloplasty (%) | 53 (36.1) | 63 (42.9) | 0.233† | |

| Aortic valve replacement (%) | 4 (2.7) | 7 (4.8) | 0.357‡ | |

| Ascending aorta replacement (%) | 101 (68.7) | 104 (70.7) | 0.703† | |

| Total arch replacement + FET (%) | 147 (100) | 147 (100) | 1.000‡ | |

| Arterial perfusion position | Innominate artery (%) | 125 (85.0) | 127 (86.4) | 0.739† |

| RSA (%) | 3 (2.0) | 3 (2.0) | 1.000‡ | |

| RCCA (%) | 4 (2.7) | 3 (2.0) | 0.702‡ | |

| LCCA (%) | 12 (8.2) | 13 (8.8) | 0.834‡ | |

| CPB time (min) | 158 (140, 187) | 158 (139, 180) | 0.699* | |

| Cross-clamp time (min) | 97 (81, 112) | 90 (77, 103) | 0.068* | |

| Circulatory arrest (min) | 5 (4, 7) | 16 (13, 29) | ||

| Lowest rSO2 (%) | 58 (53, 67) | 62 (57, 66) | 0.023* | |

| Min. rectal T (°C) | 31.8 (30.8, 32.3) | 29.7 (29.2, 30.4) | ||

| Min. nasopharyngeal T (°C) | 29.4 (28.7, 30.3) | 27.5 (26.8, 27.9) | ||

FET, frozen elephant trunk; CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass; CA, circulatory arrest; RSA, right subclavian artery; RCCA, right common carotid artery; LCCA, left common carotid artery; lowest rSO2, lowest regional cerebral oxygenation index; Min. rectal T, minimum rectal temperature; Min. nasopharyngeal T, minimum nasopharyngeal temperature.

*Mann–Whitney U test; †Chi-squared test; ‡Fisher’s exact probability test.

The main findings of this study were that 24-hour postoperative ALT levels and the incidence of AKI were significantly lower in the MI group compared to the MO group. In contrast, the incidence of TND and PND did not differ significantly between the groups. These results suggest that MiHCA combined with LABP can be safely and effectively implemented, with improved protection of lower-body organs, consistent with previous retrospective studies [8, 9, 10, 11].

Reducing circulatory arrest (CA) time has been widely explored as a key strategy to protect lower-body organs during aortic arch surgery [8, 11, 12, 13]. For example, the use of endo-balloon occlusion combined with femoral artery retrograde perfusion has been shown to significantly shorten CA time while reducing the incidence of AKI at higher CA temperatures [11, 14]. Similarly, retrograde inferior vena caval perfusion has been used to reduce or avoid lower-body ischemia, resulting in non-inferior outcomes regarding postoperative renal failure, liver dysfunction, and AKI [12]. From a mechanistic standpoint, prolonged CA is known to increase the risk of ischemia-reperfusion injury, oxidative stress, and systemic inflammation—key drivers of postoperative organ dysfunction. LABP may mitigate these effects by maintaining distal perfusion during arrest, preserving microvascular integrity, and reducing tissue hypoxia. Additionally, the use of mild hypothermia may help avoid the adverse effects of deep hypothermia and rewarming-related neurological injury, while ensuring adequate metabolic protection. These factors provide a plausible explanation for the lower incidence of AKI and improved hepatic function observed in the MiHCA + LABP group.

Similar to previous research [8, 13], our study employed antegrade perfusion with balloon occlusion. LABP provided oxygenated blood to the lower body, reducing the CA time from 16 to 5 minutes. This was associated with a significant reduction in postoperative ALT levels and a decrease in the incidence of AKI. This protective effect may be attributed to the significant decrease in ischemia time (5 vs. 16 minutes; p = 0.000), with LABP offering perfusion flow comparable to that delivered via a standard 4-branch prosthetic graft. However, while liver injury and overall AKI incidence were improved, the rate of acute renal failure was not significantly different between groups. This may reflect the complexity of renal injury mechanisms and the need for longer-term follow-up or larger sample sizes. Nonetheless, LABP ensured more continuous blood flow to vital organs during the procedure, even at a higher operative temperature. Additionally, the use of LABP allows for a more controlled and less time-constrained distal anastomosis, which can be especially beneficial for less experienced surgeons performing TAR.

Previous studies have shown that mild hypothermia involves only 3–5 °C of rewarming, while moderate-to-deep hypothermia requires 10–20 °C of rewarming, which is associated with a higher risk of rewarming-induced neuroinjury [6]. BSACP has also been shown to provide improved cerebral protection compared to unilateral perfusion [15, 16]. Several surgical teams have successfully performed TAR under mild hypothermia with favorable outcomes [17, 18]. However, this study observed no significant difference in the incidence of TND or PND between the MI and MO groups, despite the MI group showing significantly lower intraoperative regional cerebral oxygen saturation (rSO2) levels (58% vs. 62%; p = 0.023). This finding may suggest that the modest 2 °C difference in nasopharyngeal temperature between the groups was not sufficient to affect rewarming-related neurological outcomes. Our results are consistent with previous studies, which report no clear neurological advantage of mild hypothermia over moderate in the setting of well-maintained cerebral perfusion. These findings highlight the need for future investigations to more precisely define the threshold at which temperature differences during circulatory arrest translate into clinically meaningful neurological effects.

Finally, our findings confirm that the single UHS approach remains suitable for total arch replacement, even when combined with LABP.

This study has several limitations. First, we compared MiHCA combined with LABP against MoHCA alone, introducing two variables—higher circulatory arrest temperature and LABP—in the MI group. However, based on prior studies demonstrating that LABP under MoHCA already improves outcomes compared to MoHCA alone, and considering that LABP may help counteract the metabolic stress associated with higher temperatures, we treated these combinations as two distinct surgical strategies rather than as isolated variables. Nonetheless, because the individual effects of temperature and LABP were not independently assessed, future studies should include an additional group that receives MoHCA plus LABP to promote more accurate comparisons among the three strategies. Second, the sample size was relatively small, which may have limited the statistical power of some analyses. Therefore, further studies with larger cohorts are necessary to confirm the observed trends and investigate additional clinical effects. Lastly, this was a single-center trial performed by a specialized surgical team, which may limit the generalizability of the results. A multicenter randomized controlled trial is required to evaluate the broader applicability of this approach.

This study supports our previous findings, suggesting that MiHCA combined with LABP via a single UHS is a safe and feasible treatment option for acute type A aortic dissection. LABP significantly shortens the time of circulatory arrest and is associated with reduced postoperative ALT levels and a lower incidence of AKI, indicating improved protection of lower-body organs.

The study protocol and individual participant data supporting the results reported are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

YL and LX performed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. ZY, YG, LW, BW, and XX assisted in performing the experiments and prepared all the figures. YL designed the study and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to its accuracy or integrity.

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the General Hospital of Northern Theater Command (Approval No. K2020.19). It was prospectively registered with the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR2000033852) prior to patient enrollment. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before randomization. This manuscript complies with the CONSORT reporting guidelines.

Not applicable.

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Province (2023JH2/101700107 and 2023JH6/100100034).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.