1 Robotic Cardiac Surgery Unit, Humanitas Gavazzeni Hospital, 24125 Bergamo, Italy

2 Electrophysiology Unit, Humanitas Gavazzeni Hospital, 24125 Bergamo, Italy

3 Department of Anesthesia, Humanitas Gavazzeni Hospital, 24125 Bergamo, Italy

4 Department of Experimental Medicine, University of Rome “Tor Vergata”, 00133 Rome, Italy

5 Advanced Cardiovascular Imaging Unit, Humanitas Gavazzeni Hospital, 24125 Bergamo, Italy

6 Department of Experimental and Clinical Medicine, Magna Graecia University, 88100 Catanzaro, Italy

7 Department of Cardiac Surgery, Paracelsus Medical University, 90419 Nuremberg, Germany

Abstract

Robotic-assisted ablation of atrial fibrillation (RA-AF) is a minimally invasive procedure that requires accurate planning and anatomical assessment to reduce the risk of complications: Cardiac Magnetic Resonance (CMR) can safely be used for pre-procedural planning, providing good quality images without the use of ionizing radiation. The aim of the study is to evaluate how CMR can be used to assist the surgeon in the planning and execution of a safe and effective robotic-assisted procedure.

A single-center observational study of 27 patients (25 persistent AF, 2 paroxysmal AF) undergoing robotic-assisted left atrial epicardial ablation with left atrial appendage exclusion. CMR was used in 22 patients; 5 underwent CT due to contraindications. Three-dimensional CMR reconstructions were reviewed preoperatively to optimize probe placement and energy delivery. The contrast agent used was gadoteridol (ProHance®, Bracco Imaging, Milan, Italy; catalog no. 117258).

Mean age was 64 ± 7 years; 81% were male. Hypertension (81%) and diabetes (22%) were common comorbidities. CMR showed enlarged LA (volume index 76 ± 17.6 mL/m2) and fibrosis predominantly on the LA roof (81%) and lateral wall (45%). No LAA thrombi were observed. All patients underwent successful robotic AF ablation with no intraoperative ischemic or bleeding complications. 3D CMR reconstructions facilitated intraoperative surgical guidance.

CMR-guided robotic AF ablation is feasible, safe, and effective. Pre-procedural fibrosis mapping and 3D anatomical visualization enhance surgical planning and may improve outcomes. Larger prospective studies are required to confirm prognostic value.

Keywords

- robotic-assisted cardiac surgery

- CMR

- atrial fibrillation

- surgical ablation

In recent years, cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) has played an increasingly important role in the pre-procedural evaluation of atrial fibrillation (AF) ablation procedures. In this scenario, it could play a similarly useful role in the planning of robotic-assisted AF ablation. Indeed, in addition to anatomical evaluations that allow for the personalized placement of surgical instruments for robotic-assisted surgery, CMR represents a research tool to investigate a possible pathological substrate of AF like left atrial (LA) fibrosis, which can guide the positioning of the ablation probe and energy delivery to achieve an effective ablation line. For these reasons and thanks to the development of semiautomated software, CMR has emerged as a key exam in the management flowchart of AF patients [1]. This study aims to provide an overview of the use of CMR in the pre-procedural work-up for robotic AF surgical ablation in our current clinical practice, showing how this radiation-free technique can be useful in pre-procedural planning and how it is a valid alternative to standard computed tomography (CT) evaluation.

This is a case-series observational study of a single center with experience in minimally invasive surgery and robotic surgery for the treatment of AF. The study involved 27 patients with AF (25 persistent AF, 2 paroxysmal AF) undergoing robotic-assisted LA epicardial ablation, according to the surgical technique previously described [2]. The procedure was completed with epicardial exclusion of the left atrial appendage (LAA) using epicardial clip (Atriclip Device AtriCure Inc., Mason, OH, USA).

Patients were enrolled from April 2023 to August 2024 at the Humanitas Gavazzeni Hospital in Bergamo, Italy.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were based on the latest European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines for the hybrid treatment of AF. Eligible patients were between 18 and 75 years of age, with symptomatic persistent or long standing AF, who met at least two of the following criteria: (1) no response or intolerance to at least two classes of antiarrhythmic drugs, (2) previous failed percutaneous AF ablation procedures, and (3) evident risk factors for AF recurrence after transcatheter ablation, including body mass index (BMI)

Exclusion criteria included patients who had previously undergone cardiac surgery, patients with severe pulmonary disease unable to withstand monopulmonary ventilation, and patients with non-CMR-compatible devices.

All patients provided written informed consent for the procedure, data and sample collection/use and/or publication of data results. The patient clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1.

| Patients Number: 27 | ||

| Age | 64 | |

| Gender Male | 22 (81%) | |

| Family History of AF | 5 (18%) | |

| Average AF duration (years) | 4 | |

| Previous ECV | 15 (55%) | |

| Previous transcatheter endocardial ablation | 9 (33%) | |

| Mean Ejection Fraction | 56 | |

| Medical history | ||

| Hypertension | 22 (81%) | |

| Diabetes | 6 (22%) | |

| COPD | 0 | |

| Dyslipidemia | 10 (37%) | |

| Stroke | 0 | |

| Mean BMI | 29.61 | |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score | 1.82 | |

| Type of AF | ||

| Persistent AF | 16 (59%) | |

| Long-standing persistent AF | 11 (40%) | |

AF, atrial fibrillation; ECV, electrical cardioversion; COPD, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; BMI, body mass index.

All patients underwent an imaging test to confirm the anatomical suitability and technical feasibility of the procedure. The robotic-assisted epicardial surgical ablation and LAA closure through left thoracoscopy was performed by a single operator using the Da Vinci X Surgical System (Intuitive Surgical Inc., Sunnyvale, CA, USA) and the Episense device (AtriCure Inc., Mason, OH, USA). Patients were monitored intraoperatively with transesophageal echocardiography.

CMR was the imaging technique of choice and it was performed in 22 patients. Cardiac computed tomography (CCT) was performed in 5 patients with contraindications to CMR (e.g., claustrophobia, metallic implants, or non-CMR-conditional devices).

CMR imaging was performed on a 1.5 T magnetic resonance scanner (Philips Achieva, Philips Medical Systems, Best, The Netherlands; and Siemens Aera, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany). All patients underwent a detailed standard assessment, including Steady-State Free Precession (SSFP) sequences for left ventricular (LV) and right ventricular (RV) volumes and function. Conventional contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance angiography (CE-MRA) of the pulmonary vasculature was obtained in an axial orientation using a three-dimensional (3D) gradient echo FLASH pulse sequence with an average slice thickness of 1.3 mm. A centric phase-encoding acquisition was used. A bolus of 0.15 mmol/kg of gadoteridol (ProHance®, Bracco Imaging, Milan, Italy; catalog no. 117258) was injected at a rate of 3.5 mL/s via an intravenous cannula in the antecubital fossa. An oblique image of the heart in 4-chamber view was acquired every second during contrast injection, and image acquisition was then manually triggered by the operator upon visualization of the contrast bolus in the left atrium. CE-MRA acquisition time was approximately 20 s.

Early enhancement sequences were done immediately after CE-MRA to detect the presence of LAA thrombosis (2-chamber or short-axis view). A 3D late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) sequence was acquired 8 min after contrast injection. The sequence is an inversion recovery prepared respiratory triggered and navigated, ECG-gated, and fat-suppressed fast spoiled gradient echo sequence (repetition time 2.5 to 5.5 ms, echo time 1.52 ms, field of view 340 mm, flip angle 10°, inversion time 240 to 300 ms, 1.3

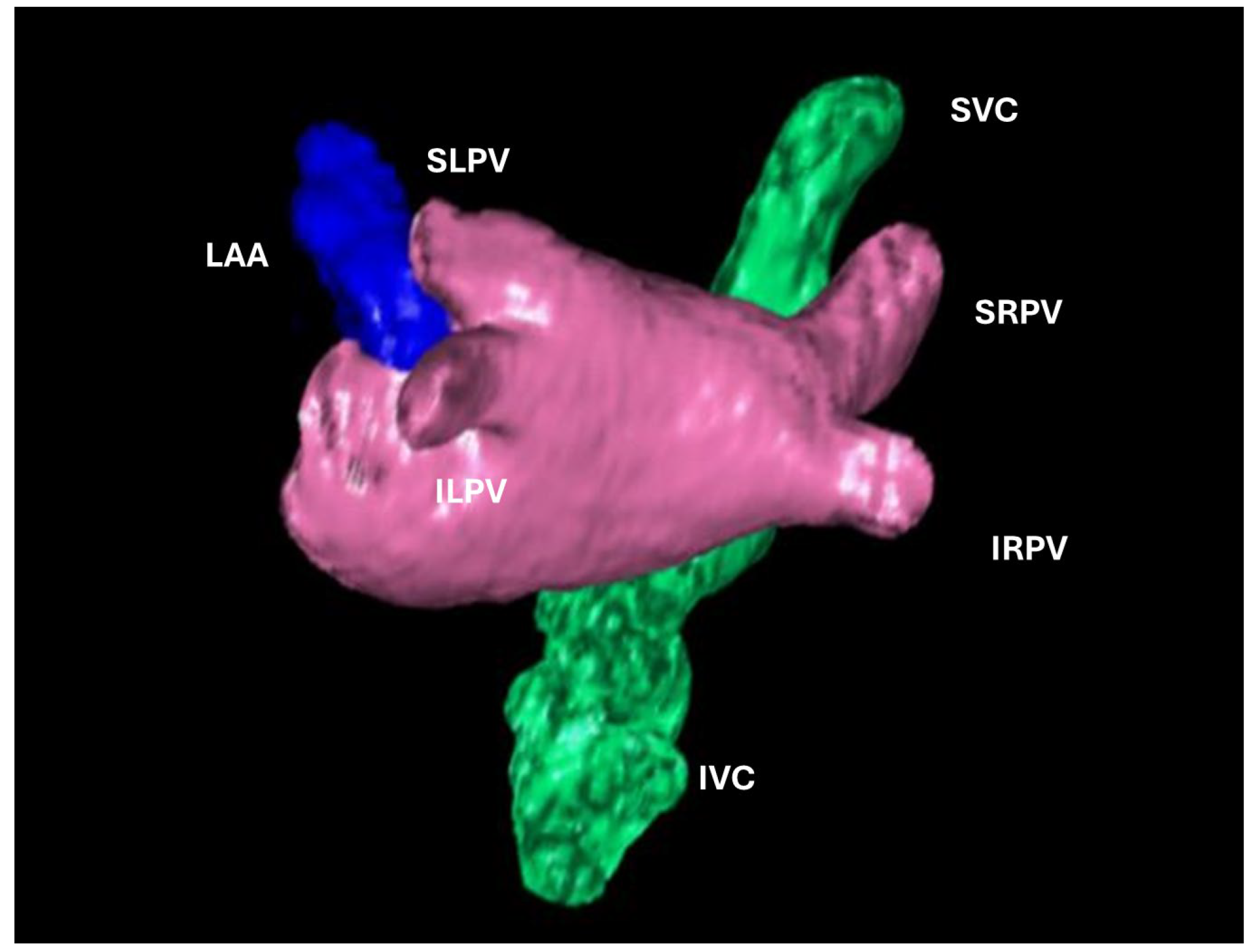

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. 3D volume rendering of the left atrium (LA). left atrial appendage (LAA), pulmonary veins (SRPV, superior right pulmonary vein; IRPV, inferior right pulmonary vein; SLPV, superior left pulmonary vein; ILPV, inferior left pulmonary vein), superior vena cava (SVC) and inferior vena cava (IVC).

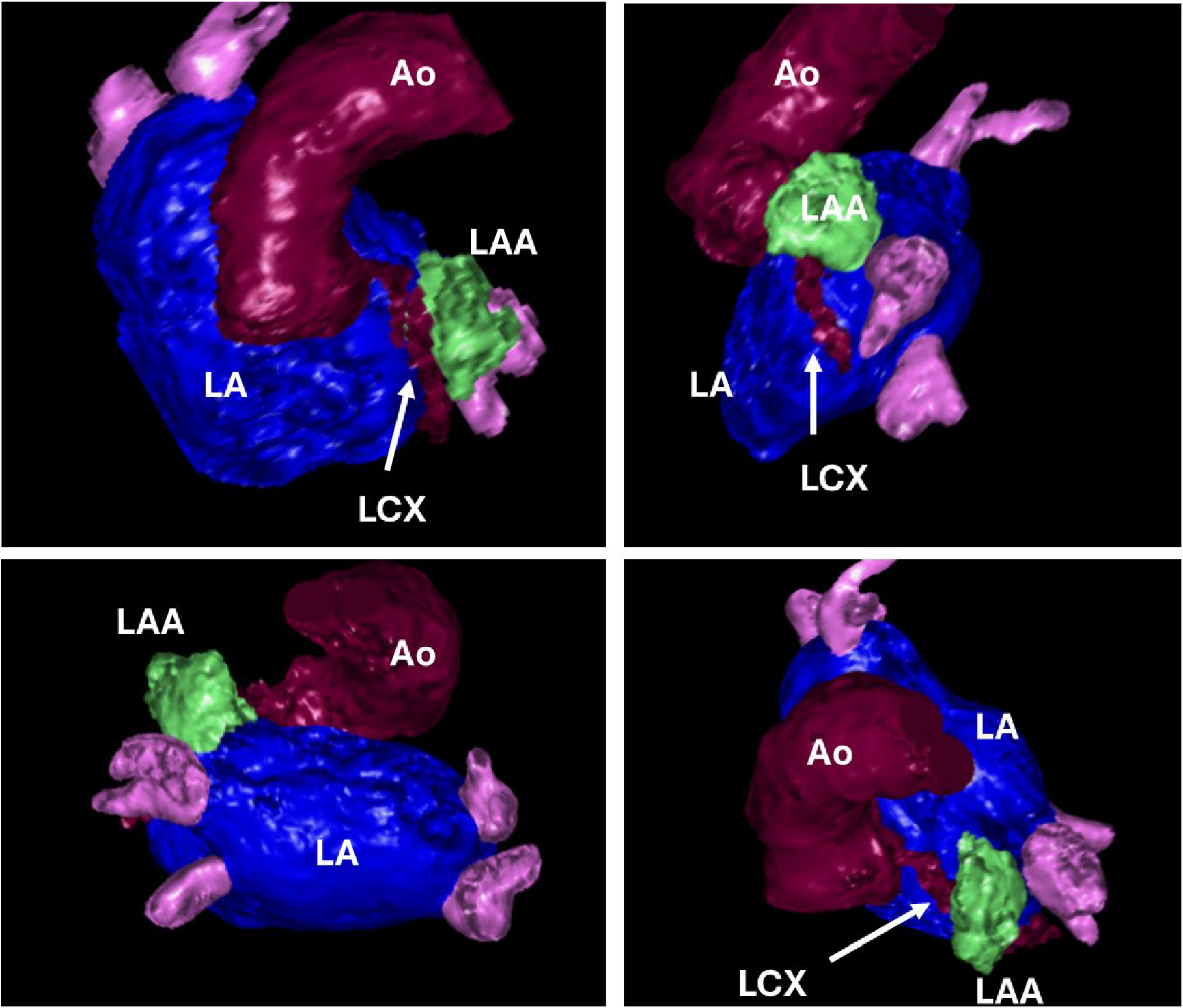

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. 3D volume rendering of the left atrium (LA), left atrial appendage (LAA), ascending aorta (Ao) and left circumflex artery indicated with an arrow (LCX).

Image quality was assessed by two expert readers and classified with a 0–5 quality score (0 = no artifacts; 1 = minor artifacts not affecting imaging evaluation; 2 = minor artifacts affecting imaging of less than 25% of images; 3 = moderate artifacts affecting 25–50% of images; 4 = severe artifacts affecting more than 50% of images; 5 = not evaluable exam).

3D reconstructions of the left atrium were reviewed and discussed with surgeons before the procedure, focusing on the number of PV, their location and the relation to other structures of the thorax. LA LGE location and extension were used as a surrogate for disease severity, expressed in terms of number of segments involved by visual evaluation. The total amount of LA LGE was measured quantitatively with dedicated software, and was discussed at a later stage with an electrophysiologist and matched with endo-cavitary potentials, measured with electroanatomic mapping during the second phase of the hybrid treatment.

Table 2 displays the cohort-averaged magnetic resonance datasets. Considering LAA morphology, chicken-wing was the predominant shape (n = 9, 41%): which leads to the use of a longer device for LAA closure. LA LGE identified extensive pathological substrates on the LA roof (n = 18, 81%) and lateral wall (n = 10, 45%). No thrombus was found. All patients met the anatomical characteristics suitable for the robotic approach. All patients underwent robotic AF ablation without intraoperative ischemic or bleeding complications and with an easy interpretation of the anatomical structures guided by 3D CMR reconstructions: images were put on a DaVinci screen and the location of LA fibrosis detected by CMR was taken into consideration during the execution of the ablation lines.

| Parameters | Mean | SD |

| LVEDV (mL) | 140 | 30 |

| LVEDV index (mL/m2) | 68 | 13 |

| IVS (mm) | 10 | 2 |

| LV wall (mm) | 9 | 1.5 |

| LV SV (mL) | 72 | 20 |

| LV mass index (g/m2) | 48 | 9 |

| LVEF (%) | 51 | 10.5 |

| RVEDV (mL) | 138 | 31 |

| RVEDV index (mL/m2) | 67 | 16 |

| RV SV (mL) | 72 | 18 |

| RVEF (%) | 53 | 9 |

| RV diameter (mm) | 46 | 5 |

| PE | 0 | |

| Native T1 mapping (ms) | 1012 | 29.5 |

| ECV (%) | 25 | 2.5 |

| LV LGE (n) | 5 | |

| RV LGE (n) | 0 | |

| Pericardial enhancement (n) | 0 | |

| LA volume (mL) | 156 | 31.5 |

| LA volume index (mL/m2) | 76 | 17.6 |

| Left atrial appendage (mL) | 14 | 6 |

| Number of pulmonary veins (n) | 4 | |

| LA LGE (n) | 21 | |

| LGE in LA roof (n) | 18 | |

| LGE LA anterior wall (n) | 5 | |

| LGE LA septal wall (n) | 5 | |

| LGE LA lateral wall (n) | 10 | |

| LGE LA inferior wall (n) | 5 | |

| Quality score | 1.2 | 0.9 |

CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance; IVS, interventricular septum; LA, left atrial; ECV, extracellular volume; LGE, late gadolinium enhancement; LV, left ventricular; LVEDV, left ventricular end-diastolic volume; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; PE, Pericardial Effusion; RV, right ventricular; RVEDV, right ventricular end-diastolic volume; RVEF, right ventricular ejection fraction; SV, stroke volume.

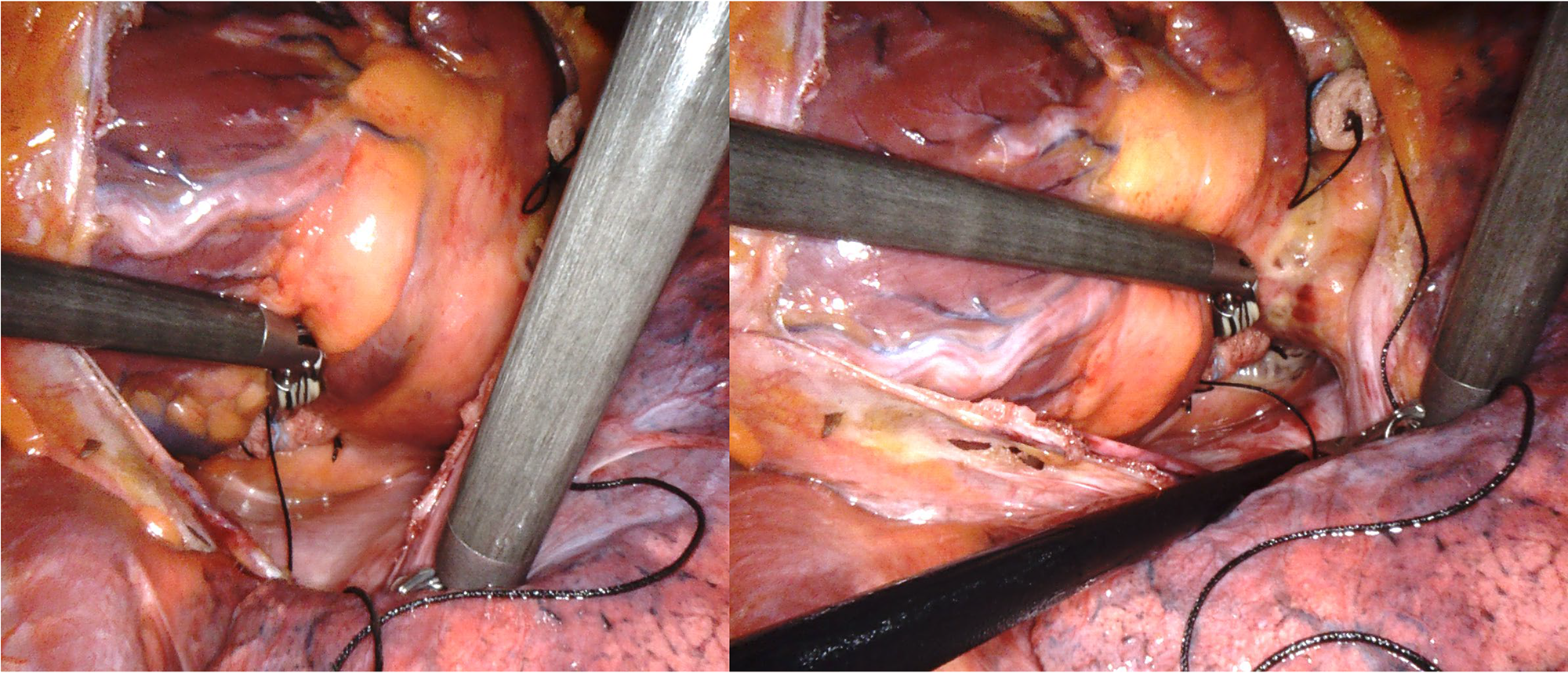

European guidelines for the management of AF define percutaneous pulmonary vein (PV) ablation as a first-line treatment within a shared decision-making rhythm control strategy in patients with paroxysmal AF, to reduce symptom, recurrence, and progression of AF [3]. However, sub-optimal outcomes of catheter ablation (CA) in patients with persistent or long-standing persistent AF have driven the pursuit of alternative methodologies. Surgical ablation represented by the Cox-Maze Technique has proven to be a safe and effective technique in sinus rhythm restoration [4]. However, the invasiveness of the procedure and higher risk of post operative complications compared with the transcatheter approach limits its use, especially to concomitant cardiac surgery. In fact, the first Cox Maze procedure required full sternotomy and cardiopulmonary bypass to perform a complete set of lesions, including both the left and right atrium and epi/endocardial ablation lines [5]. To emulate the success of the Cox-Maze procedure while minimizing invasiveness, closed-chest thoracoscopic epicardial PVI has been developed. The advent of robotic technology has further enhanced these procedures, offering improved precision by magnified visualization and dexterity optimization. These features allow precise positioning and control of the ablation probe and a better control of surrounding cardiac structures, reducing the risk of damage (Fig. 3). These characteristics also facilitated access and extended ablation beyond the PVs to the posterior wall, roof and floor of the LA and left auricle. A preliminary study of our center [2] described encouraging results of this technique in term of safety and feasibility.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Intraoperative robotic vision during ablation procedure.

A cornerstone of the technique is based on its customization to the patient, which requires in-depth anatomical knowledge to avoid chest or cardiac lesions, especially during the first phase of the “learning curve” [6].

Appropriate pre-procedural planning is essential to define suitable patients, and, in this scenario, advanced cardiac imaging techniques play a crucial role. Pre-procedure CCT and CMR angiography are commonly used to delineate the complex and variable relationship between the LA, PV, and surrounding structures. CCT provides high spatial resolution, while CMR has a low spatial resolution but may be helpful for myocardial tissue characterization. This limitation could be very relevant when assessing small vessels, such as coronary arteries but, considering the dimensions of PVs, LA and LAA, the spatial resolution of CMR is good enough to obtain an accurate pre-procedural evaluation. Despite CCT and CMR providing similar anatomical information [7], CMR is associated with a lower overall cumulative radiation exposure and doesn’t require iodinated contrast medium, which is advantageous, especially in patients suffering from renal insufficiency or allergic reactions.

By studying the anatomy of the chest and its anatomical relationship to the heart, the surgical ports can be placed on the chest wall by aligning them with the cardiac structures to be treated, thus avoiding conflicts between the robotic instruments during movement.

Heart anatomical characteristics described by cardiac imaging, such as number, location, morphology and anatomical relationship of PVs, are very important to guide ablation probe positioning before radiofrequency delivery. CMR with angiographic sequences can depict PV anatomy, provide accurate PV ostia sizing, and identify anatomical variations (accessory PV, common ostium) or abnormalities (anomalous pulmonary venous return), with a very high reproducibility if compared to standard cardiac CT images. In this way, complete ablative lines can be obtained around the PVs avoiding damage to surrounding cardiac structures, especially the superior vena cava. Empirical evidence suggests that one of the main challenges with this procedure is superior vena cava damage due to incorrect positioning of the radiofrequency probe.

Moreover, the evaluation of LA size is crucial for risk stratification in patients with AF, especially persistent AF. First, LA volume influences the success of the ablation strategy: the greater the dilatation of the left atrium, the less effective the maintenance of the RS at follow-up. LA enlargement also represents an independent risk factor and predictor of stroke and death in patients with AF [8]. Although transthoracic echocardiography is the standard method in clinical practice for the assessment of LA size, CMR is considered the standard reference for cardiac volume assessment, including LA volumes, because SSFP techniques or angiographic 3D acquisitions do not rely on geometrical assumptions.

Another strength of CMR is its ability to assess the degree of atrial fibrosis with LGE, which can help guide the surgical ablation. Knowledge of fibrosis combined with direct monitoring of impedance trends and disappearance of the atrial electrogram guided the placement of the ablation probe and energy deliveries. Specifically, the number of ablation lines and the number of energy deliveries were reduced in these identified areas, knowing that these same areas could not be avoided completely.

AF is known to initiate and perpetuate electrical and structural remodeling, which can ultimately lead to maladaptive consequences, including myocardial apoptosis and subsequent collagen deposition, known as replacement fibrosis. The location and extent of atrial myopathy can be quantitatively assessed by CMR and it will be included in our future analysis. In our first case series, we only considered the visual levels of LA fibrosis. Data regarding the prognostic impact of the quantitative analysis will be considered as a second step of AF treatment, represented by electrophysiological assessment and endocardial LA ablation, in a hybrid treatment protocol (surgical + Endo cavitary) of AF. Even if hypothesis-generating, the larger part of our study population showed LGE involving the atrial roof (posterior LA wall), and this is consistent with the good result of the robotic procedure, focused mainly in creating ablative lines in that region. Moreover, CMR demonstrated a high prevalence of interstitial fibrosis in this area [9], and electrophysiology studies have shown the high prevalence of autonomic ganglionic plexi and macro-reentrant circuits that may also contribute to AF substrates [8]. Although the current results from DECAAF II do not provide evidence that CMR-guided fibrosis ablation improves AF recurrence in the setting of persistent AF, knowing the distribution and extension of fibrosis can help guide decisions on the extension and orientation of the ablative lines to follow, improving mid- and long-term outcomes [1]. These hypotheses have to be confirmed and compared to endocavitary electrophysiology mapping and long-term follow-up.

Another point to take into consideration when talking about CMR imaging is the uniqueness that this method provides in defining the tissue characteristics of the LV myocardium. Defining LV LGE is crucial as it was found to be associated with a higher probability of arrhythmia recurrence rates after ablation [10].

In conclusion, in the current scenario where robotic-assisted epicardial surgical ablation has demonstrated encouraging persistent and long-standing AF, especially in a context of hybrid strategy, CMR has an important role in pre-procedural planning, providing detailed anatomical and pathological insights into the LA and surrounding structures. The ability of CMR to assess atrial fibrosis and tissue characteristics contributes significantly to planning ablation strategies, although further studies are needed to assess its true prognostic impact and thus improve surgical ablation strategy and patient selection. Moreover, integrating advanced imaging techniques such as CMR will likely continue to play a pivotal role in enhancing the efficacy and safety of these procedures, ultimately improving patient outcomes in the treatment of AF.

Our study has several limitations. The first being represented by its retrospective nature, meaning patient selection and observer biases are expected, as they are inherent to the introduction of a newer technique. Second, larger cohorts and, possibly, randomized studies including comparable control groups, such as patients treated with the endocardial catheter approach, will be necessary to draw a causal conclusion of efficacy. Third, to better evaluate the impact of atrial fibrosis on ablation success, patients should undergo a post-surgical ablation electrophysiological study, as provided by a hybrid AF treatment protocol.

Our findings demonstrate that CMR-guided robotic AF ablation is a safe, feasible, and highly effective approach for patients with persistent and long-standing AF. By providing precise anatomical and tissue characterization, CMR substantially improves pre-procedural planning and intraoperative guidance, leading to complication-free procedures in our entire cohort. This strategy strengthens the hybrid treatment paradigm by enabling tailored lesion sets and enhancing procedural reproducibility. While long-term prognostic data are still needed, our results support the integration of CMR into routine planning for robotic AF ablation as a valuable step toward optimizing patient outcomes.

The data are available subject to approval by the Ethics Committee and the Health Management of Humanitas Gavazzeni Hospital, in compliance with privacy regulations.

GS, AA, MP, EC, EB designed the research study. LG, AG, RM, ML, EB performed the research. LG, RM, ML, EB analyzed the data. GS, LG, EB wrote the manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

This registry conformed to the ethical principles of Good Clinical Practice and the Helsinki Declaration and complies with current regulations. Local Institutional Review Board approval was obtained (IRCCS Humanitas Clinical Institute Rozzano, Italy: Prot. 32/23 GAV, 19 September 2023). All patients provided written informed consent for the procedure and for the use of anonymized data for research and publication.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest. Giuseppe Santarpino is serving as editor-in-chief of this journal. Eduardo Celentano is serving as one of the Editorial Board members of this journal. We declare that Giuseppe Santarpino and Eduardo Celentano had no involvement in the peer review of this article and has no access to information regarding its peer review.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.