1 Cardiovascular Surgery Division, Department of Surgery, Geneva University Hospitals (Hôpitaux Universitaires de Genève, HUG), 1205 Geneva, Switzerland

2 Anesthesiology Division, Acute medicine Department, Geneva University Hospitals (Hôpitaux Universitaires de Genève, HUG), 1205 Geneva, Switzerland

3 Faculty of Medicine, University of Geneva, 1205 Geneva, Switzerland

Abstract

Myocardial protection during cardiac surgery is critical for preserving cardiac function, minimizing ischemia-reperfusion injury, and preventing myocardial stunning. Although advances in cardioplegia formulations, delivery techniques, pharmacologic agents, and controlled reperfusion strategies have entered clinical practice, substantial variability in protocols and limited comparative evidence continue to hinder optimization and standardization. This narrative review is aimed at highlighting critical current evidence, identifying key gaps in perioperative myocardial protection, and discussing emerging opportunities for innovation and personalized strategies. A comprehensive literature search was conducted in PubMed and Embase through June 2025, with a combination of MeSH terms and keywords related to cardioplegia and myocardial protection. High-quality studies, including randomized trials, systematic reviews, and authoritative expert opinions, were selected according to relevance to key themes, including cardioplegia types, delivery techniques, risk populations, pharmacologic adjuncts, and real-time monitoring technologies. No cardioplegia strategy is universally accepted, and cardioplegic formulation composition, temperature, and delivery methods widely vary across institutions. Although modified del Nido solutions have gained popularity, comparative evidence remains inconsistent. Small volume cardioplegia solutions (e.g., Cardioplexol®) show future promise. High-risk populations, such as those with diabetes or left ventricular hypertrophy, continue to experience suboptimal outcomes, probably because of distinct metabolic and structural vulnerabilities. Pharmacologic agents mimicking ischemic preconditioning have achieved limited translation into routine practice, and remote ischemic conditioning remains underused, owing to inconsistent evidence. Real-time intraoperative monitoring of myocardial injury and established threshold values for early myocardial injury biomarkers are notably lacking. Emerging modalities such as intramyocardial pH sensors and coronary sinus metabolite sampling offer promise for early injury detection but are far from achieving widespread use. Substantial gaps persist in the personalization and standardization of myocardial protection in cardiac surgery. Innovative approaches are required to advance intraoperative sensing technologies and adjunct protective interventions tailored to patient risk profiles. Incorporating artificial intelligence, leveraging omics data, and fostering multi-institutional collaboration are key steps toward a new era of precision myocardial protection.

Keywords

- cardiac surgery

- cardioplegia

- myocardial protection

- myocardial injury

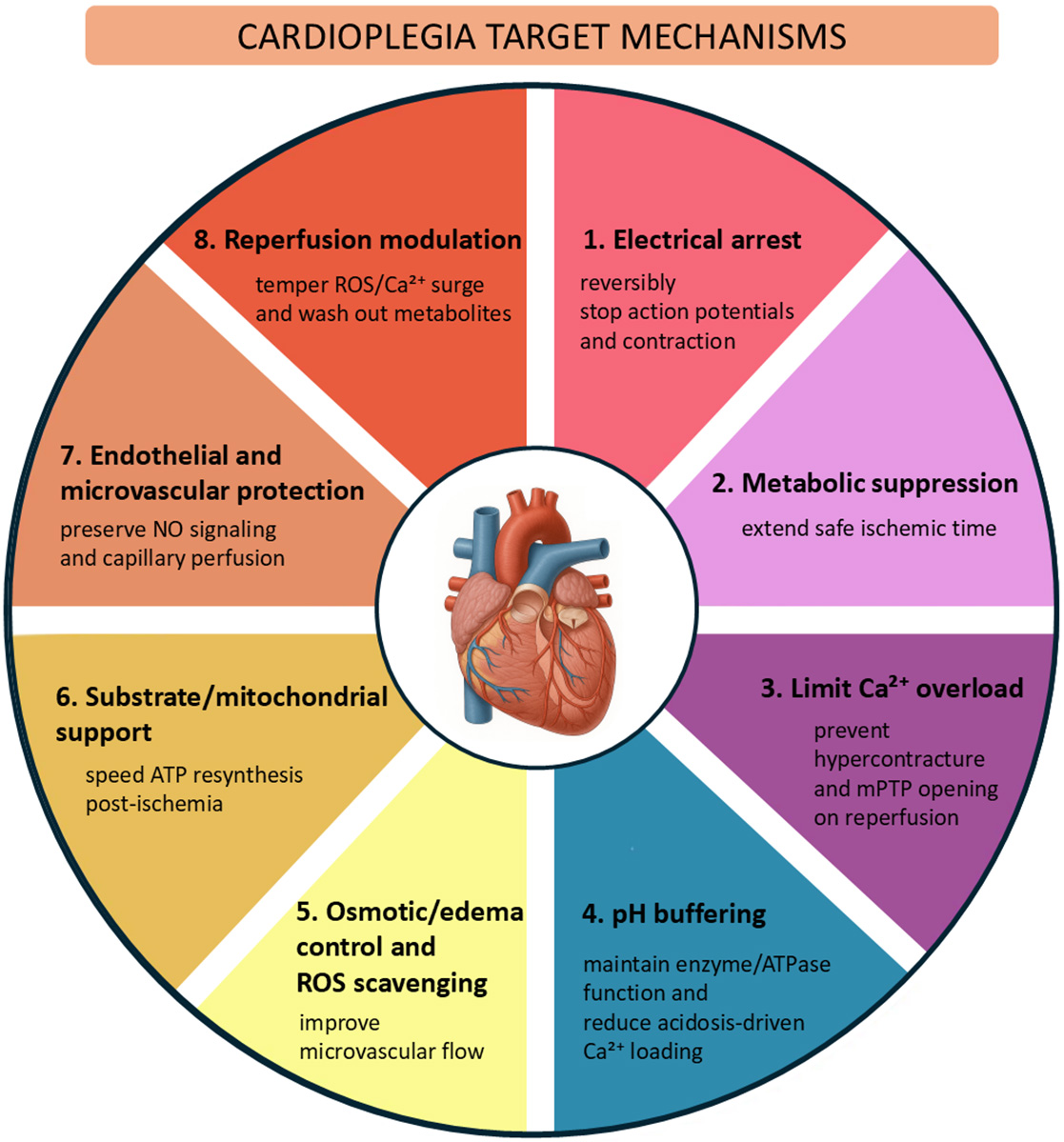

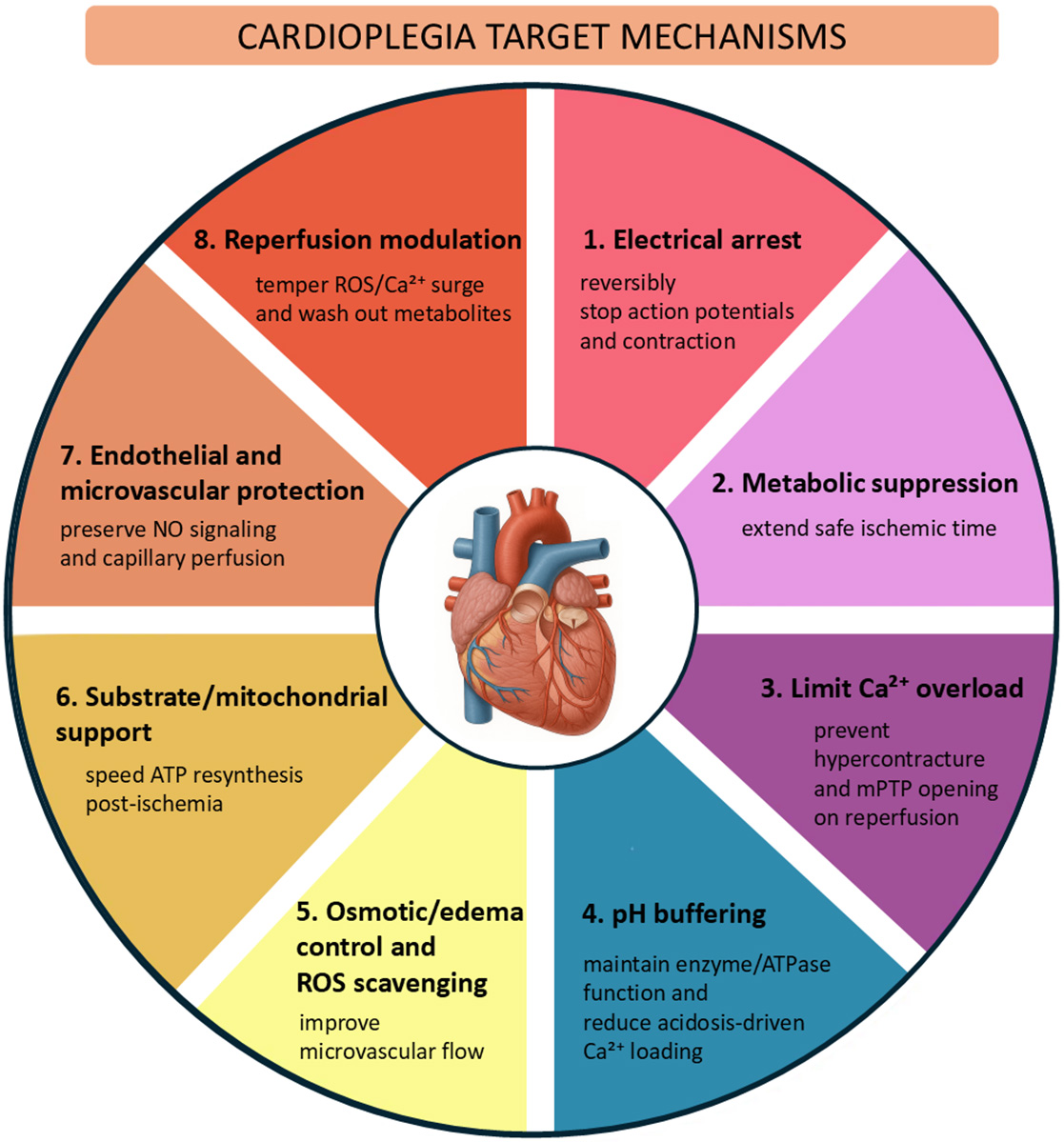

Cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass relies on the ability to create a still, clear field of view for precise operation on the heart, while protecting the myocardium against cellular damage. Minimizing injury during ischemia and reperfusion prevents myocardial stunning, the weakening of the heart muscle, and allows the myocardium to regain optimal function after aortic cross-clamp opening. The purpose of cardioplegia is to produce rapid, reversible electromechanical arrest of the myocardium and metabolic suppression, while preserving ionic/mitochondrial homeostasis and endothelial function. The protective effect of cardioplegia relies on complex intra- and extracellular mechanisms [1, 2, 3] (Fig. 1), which can be engaged only through careful design of the cardioplegic formulation composition and delivery strategy.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Core myoprotective mechanisms targeted by cardioplegia. mPTP, mitochondrial permeability transition pore; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; NO, nitric oxide; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

With advances in understanding of myocardial metabolism and physiological mechanisms of ischemia, numerous cardioplegic formulations and delivery strategies have entered clinical practice. Perioperative myoprotective strategies include the use of various anesthetic agents, pharmacological adjuncts, and controlled reperfusion techniques [1]. However, high heterogeneity in the use of these advancements persists across hospitals and surgeons. As such, the effects of each practice on outcomes are difficult to identify. To foster progress in cardiac surgery, areas that might benefit from further improvement must be addressed. In this comprehensive narrative review, we identify unmet clinical needs and provide a forward-looking view of opportunities for innovation in perioperative myocardial protection and for improving patient outcomes.

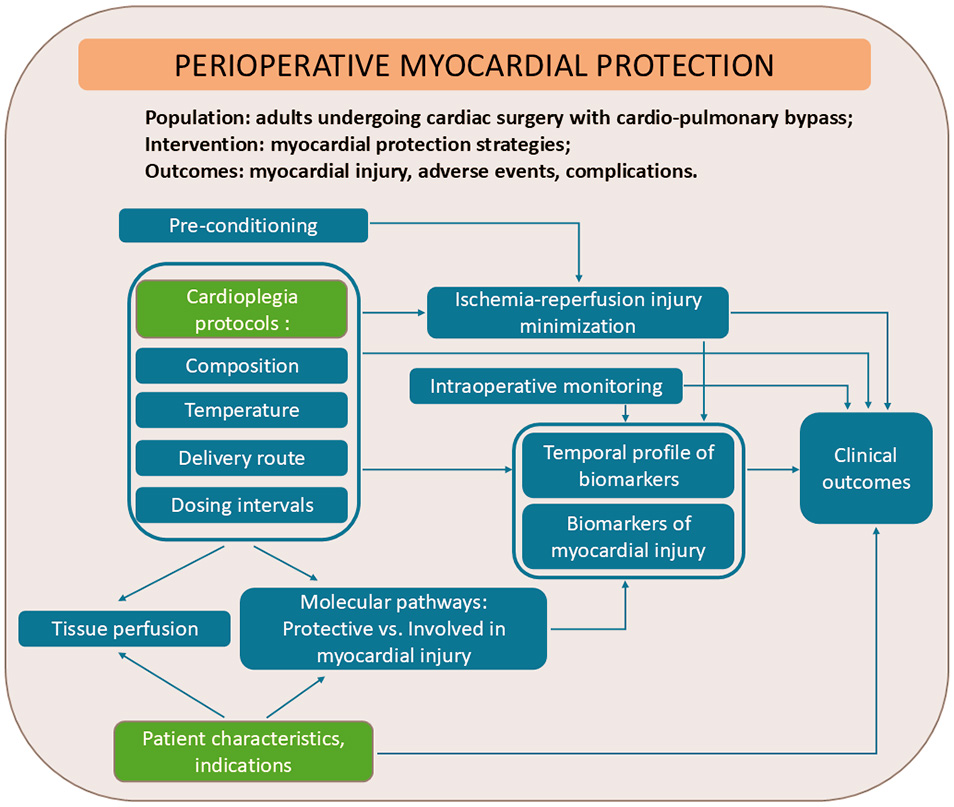

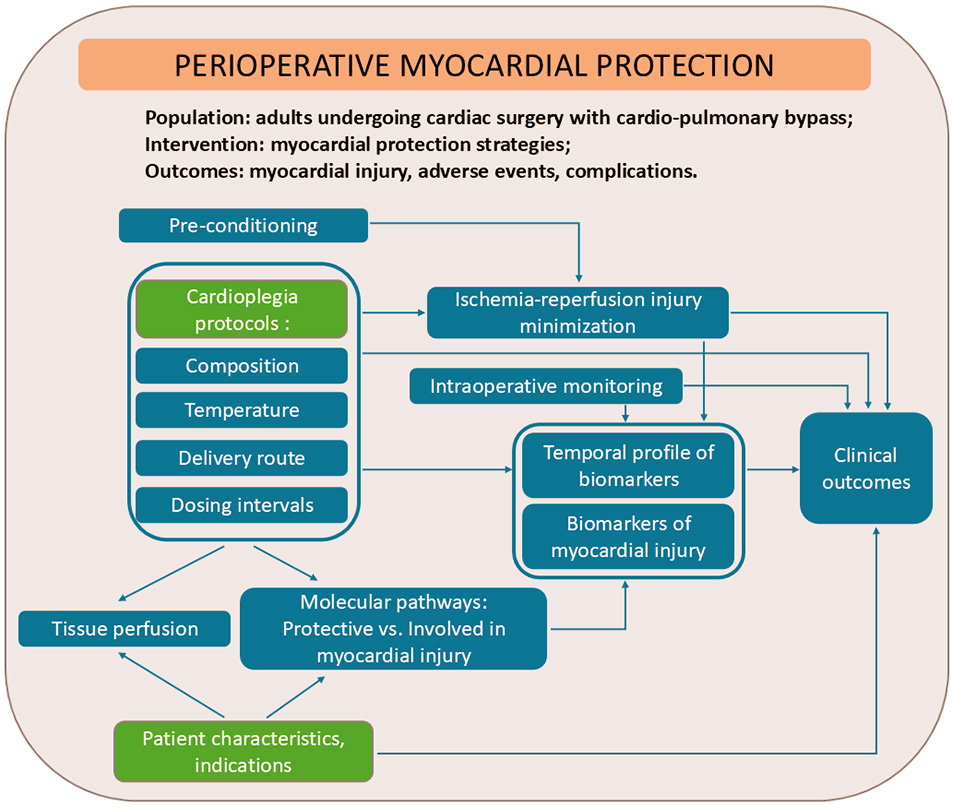

The conceptual framework presented in Fig. 2 illustrates the core elements that guided our approach to synthesizing current evidence of key gaps, challenges, and perspectives in the field of perioperative myocardial protection.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Conceptual framework for mapping current evidence and identifying current gaps in myocardial protective strategies.

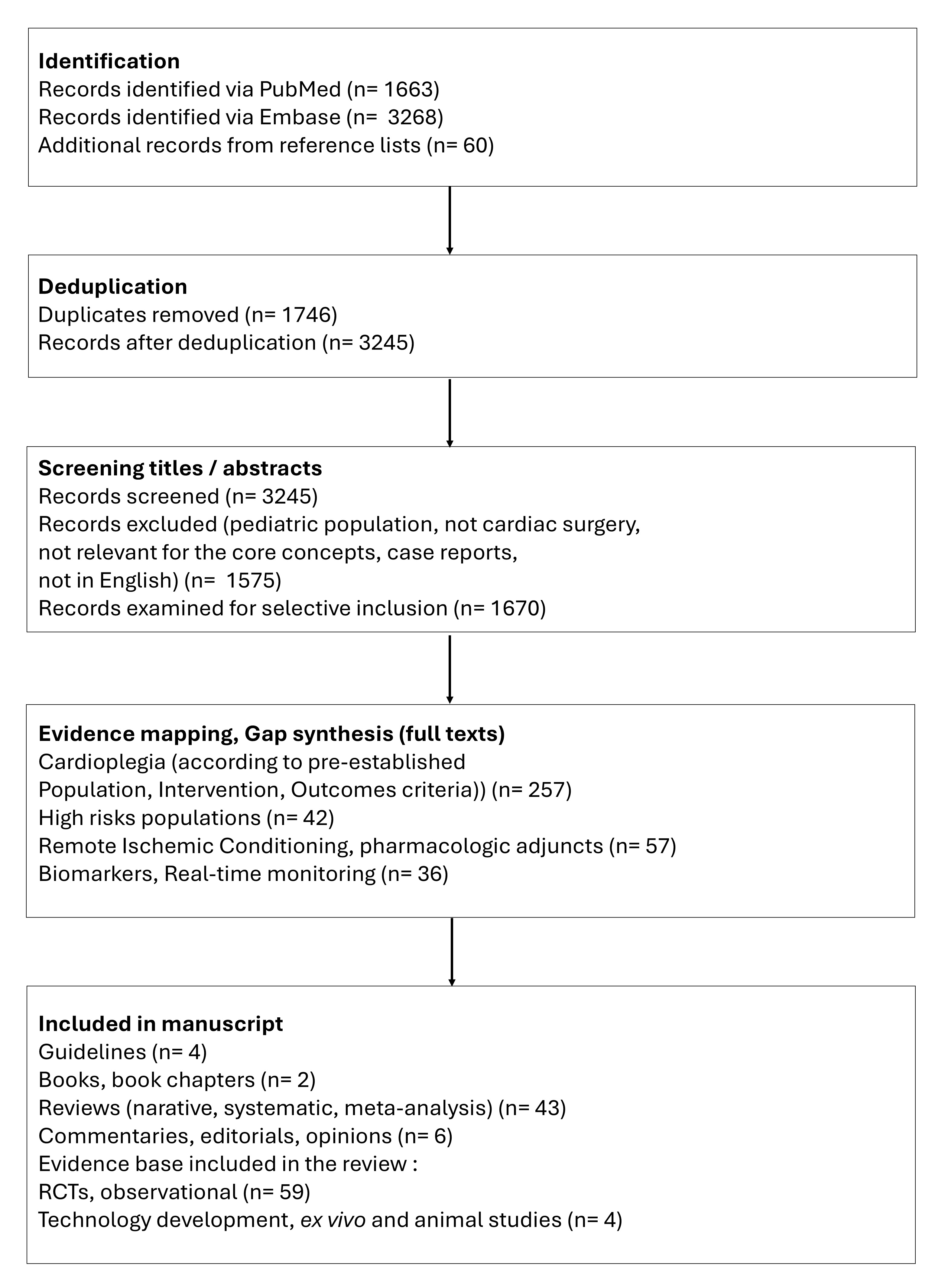

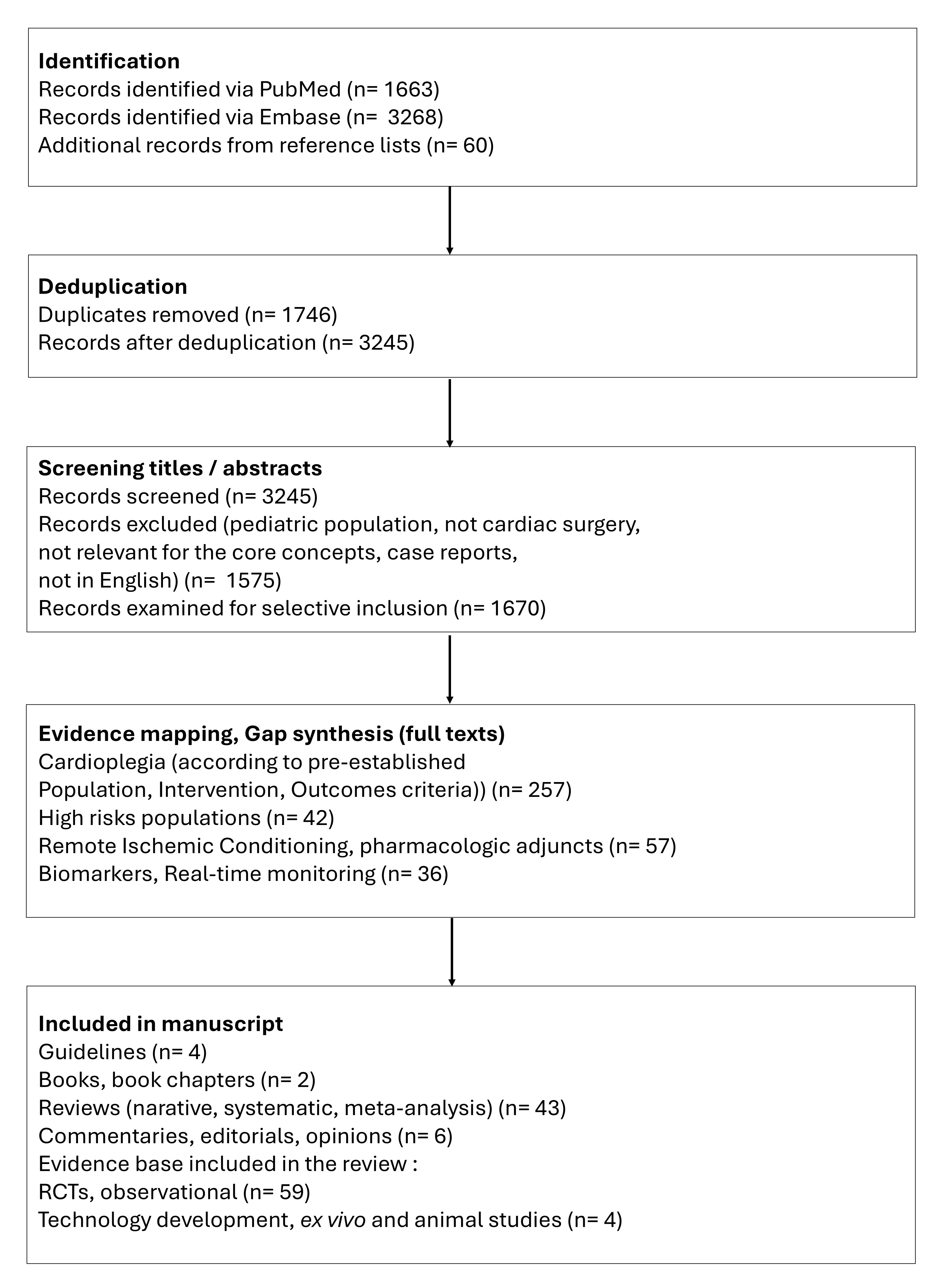

Our objective was to integrate high-quality, representative, and influential literature to inform a scholarly discussion. We performed a broad literature search in the electronic databases PubMed and Embase, examined the evidence, and incorporated expert insights to contextualize the findings. Our search included publications from database inception until June 22, 2025, with relevant MeSH terms and free-text keywords, including “cardioplegia”, “perioperative”, and “myocardial protection”. We selectively included peer-reviewed articles that addressed major concepts, controversies, evolving trends, supporting evidence, and novel hypotheses within the broad topic of interest. Content types included original research (randomized and non-randomized studies, and technical reports), systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and high-impact narrative reviews. Editorials, opinion pieces, and position statements by leading experts or societies were also selectively included when they contributed to a deeper understanding of the field. The selection process focused on conceptual relevance and contribution to scholarly discourse rather than strict methodological uniformity. The workflow is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Flow chart illustrating the study identification and selection for the comprehensive narrative review (counts are provided for transparency; this study was not a protocol-driven systematic review). RCTs, randomized clinical trials.

Despite decades of clinical use and research, substantial variability in cardioplegic formulation composition, temperature, delivery method, dosing intervals, and indications exists across cardioplegia clinical practice. Guidelines from societies such as the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS), European Society of Cardiology/European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (ESC/EACTS), and American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology (AHA/ACC) do not mandate a specific cardioplegia strategy [4, 5, 6, 7]. Most recommendations emphasize ensuring adequate myocardial protection rather than prescribing a specific solution protocol.

Topical myocardial cooling with ice slush or cold saline, in addition to cardioplegic arrest, has been used since the advent of open heart surgery and is the oldest strategy believed to decrease cardiometabolic demands [8]. A large body of evidence has indicated that topical cooling is associated with complications such as phrenic nerve paralysis, atelectasis, and pleural effusions; moreover, except in patients with long aortic cross-clamping times, it does not provide additional protective benefits when combined with cold cardioplegia [8, 9, 10, 11].

Extensive research efforts have been aimed at developing cardioplegia formulations and delivery strategies targeting different physiological mechanisms conducive to myocardial protection (summarized in Table 1, Ref. [12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22]).

| Category | Examples | Rationale | Dosing interval | Advantages | Disadvantages | |

| Crystalloid only | Extracellular mechanism | St. Thomas I/II (Plegisol/Baxter) Cardioplexol (Swiss Cardio Technologies AG, Bern, Switzerland) Bloodless del Nido (the crystalloid part of del Nido) [12] | Initially mimics extracellular fluid, then includes elevated K+ (15–30 mmol/L), which induces depolarized arrest and stops the heart in diastole. | Cardioplexol single dose lasting 45–60 min (optimized for minimal volume and simplicity, 100 mL rapid administration) [13] | Rapid induction of cardiac arrest Simplicity and ease of preparation Advantages over blood mixtures: lower viscosity, clear visual field, elimination of risk of blood-related complications (e.g., hemolysis) or metabolic issues (e.g., those associated with hemoglobin) | Risk of myocardial edema, particularly with frequent re-dosing Risk of hyperkalemia; requires electrolyte monitoring and management Potentially increased risk of ischemic events (limited oxygen-carrying capacity) Diminished effectiveness in severely hypertrophied hearts and advanced coronary artery disease |

| Provides rapid cardiac arrest and stable maintenance of arrest. | Bloodless del Nido–single dose lasting 60–90 min | |||||

| Improved formulations contain membrane stabilizing agents (to decrease electrical excitability, calcium overload, and cellular damage); osmotic agents to protect against intracellular swelling and decrease fluid accumulation (procaine and xylitol in Cardioplexol); lidocaine and mannitol (also a free radical scavenger) in bloodless del Nido; and high concentrations of magnesium, a cellular membrane stabilizer and antiarrhythmic. Dextrose, as an energy substrate, is added to bloodless del Nido [12]. | Shorter dosing interval for St. Thomas solution than for Cardioplexol or del Nido | |||||

| Intracellular mechanism | Bretschneider/histidine-tryptophan-ketoglutarate (HTK)/Custodiol (Essential Pharmaceuticals, Ewing, NJ, USA) | These formulations (low in sodium and calcium, and typically high in potassium and magnesium) suppress transmembrane ion gradients, prevent cellular calcium overload (a key cause of reperfusion injury), and hyperpolarize or depolarize the membrane, thereby arresting the heart in diastole. | Custodiol single-dose lasting 90–180 minutes [14] | Minimized interruptions during surgery (simplified workflow), because of prolonged protection Ideal for minimally invasive heart operations Decreased risk of ischemia-reperfusion injury and contracture Lowest risk of myocardial edema Low viscosity allows for even distribution in coronary circulation: useful in hypertrophied hearts and severe coronary artery disease |

Very large volume required (1–2 L), associated with several risks that must be mitigated: hemodilution (risk of bleeding), fluid overload, systemic edema (particularly in patients with impaired renal or cardiac function), systemic hypothermia, and systemic acidosis Bradycardia and delayed return to sinus rhythm, potentially because of slower washout and recovery | |

| Designed to decrease ionic shifts and mitochondrial dysfunction during ischemia-reperfusion. | ||||||

| Strong buffering (histidine) protects against acidosis. Achieves metabolic preservation (HTK). Limits interstitial fluid accumulation (osmotic agent mannitol). | ||||||

| Blood mixtures | Traditional crystalloid | Microplegia (minimally diluted blood), Buckberg (4:1 blood:crystalloid) | Oxygen and nutrients are delivered via the blood. Metabolic support helps mitigate oxidative injury during ischemia-reperfusion. | Microplegia; Calafiore (native blood, 10 mmol K+)–warm blood-based (35 °C), continuous or intermittent [15, 16, 17] | Improved myocardial oxygen delivery Maintenance of cellular energy stores and myocardial water balance Lower risk of acidosis than observed with crystalloid alone Lower risk of edema and hemodilution than observed with pure crystalloid |

Risk of hemolysis, which promotes vasoconstriction and increases microvascular resistance |

| Electrolyte control is achieved with crystalloid solution. | Buckberg cardioplegia, cold, intermittent [15, 18, 19] | Preparation complexity Potential inflammatory and immunologic effects with use of blood other than the patient’s own High viscosity potentially unsuitable for hypertrophied or very stenotic coronary beds | ||||

| Achieves improved rheology with respect to that with pure blood, and uniform cooling. | ||||||

| Del Nido formulations (crystalloid designed for prolonged myocardial protection) | Del Nido (1:4 blood:crystalloid), | Mimics intracellular ionic composition, prevents calcium influx, and provides cellular membrane stabilization. This formulation was originally developed for pediatric patients. Modified versions increase the blood content or adjust the crystalloid composition to adapt to the adult myocardium. |

Cold, single-dose lasting 60–90 min [12, 20] | Improved protection Better coronary flow | Challenging preparation Typical crystalloid risks, if crystalloid content is high Potential lidocaine toxicity and arrhythmias with overuse | |

| Modified del Nido (1:4 to 1:1 or 4:1 blood:crystalloid) | Modified by increasing the blood content; may be tepid (28 °C), single dose lasting 45 min [21] | |||||

| Specialty (obsolete) | May include calcium channel blockers (verapamil) | These formulations prevent calcium overload. | Cold, continuous or frequent intermittent [22] | Improved myocardial protection | Precise dosing necessary Risk of low cardiac output syndrome Prolonged electrical recovery and risk of bradycardia Risk of systemic hypotension | |

Cold, crystalloid based cardioplegia is performed with acellular formulations that achieve rapid cardiac arrest and a clear surgical field of view. Histidine-tryptophan-ketoglutarate (HTK), also known as Custodiol or Bretschneider’s, is an intracellular-type crystalloid cardioplegia that induces hyperpolarizing arrest through sodium/calcium withdrawal and intensive buffering. HTK contains very low Na+/Ca2+ levels and low K+, and additionally contains histidine as a strong buffer against ischemic acidosis, tryptophan for cellular membrane stabilization, alpha-ketoglutarate as a metabolic substrate for adenosine triphosphate (ATP) generation during reperfusion, and mannitol as an osmotic agent. HTK is typically administered as a single high-volume dose, often 1–2 liters, cold, and can provide prolonged protection for as long as 3 hours [23]. Potential adverse effects of HTK are associated with dilutional hyponatremia and require careful sodium management. In contrast, Cardioplexol was designed to minimize hemodilution and achieve rapid depolarizing arrest. It is typically administered at 100 mL per shot, and has advantages of decreasing the cross-clamping time and allowing for re-dosing if long clamping times are necessary. Beyond its high K+ content, Cardioplexol contains Mg2+, a calcium modulator with antiarrhythmic and reperfusion protective effects; procaine, another antiarrhythmic additive that blocks voltage gated sodium channels and achieves stable arrest; and xylitol, an osmotic agent and metabolic substrate [13]. Blood cardioplegia, through its hemoglobin and natural free radical scavengers, is believed to provide superior oxygen-carrying capacity and antioxidant protection [24, 25]. Although early data indicated increased risk of stroke and related neurological deficits when using warm blood cardioplegia compared to cold crystalloid cardioplegia, these complications were associated with the unbalanced perioperative characteristics between the groups being compared [26]. Since then, warm blood cardioplegia has been widely used and demonstrated to be safe [25]. Blood-crystalloid mixtures combine the advantages of the acellular formulations with those of blood. In hyperkalemic blood cardioplegia, known as Buckberg cardioplegia, depolarizing arrest is achieved by mixing oxygenated patient blood with a buffered, K+-rich crystalloid, with a classic blood: crystalloid ratio of 4:1, although some centers use 8:1. Traditionally, Buckberg cardioplegia is cold and requires re-dosing every 15–20 minutes [27]. A warm blood terminal dose (“hot shot”) before unclamping can aid in metabolic recovery [28]. Del Nido cardioplegia uses a hybrid formulation initially designed for pediatric patients, who are more vulnerable than adults to calcium overload and ischemia-reperfusion injury, and contains a low proportion of blood. The del Nido method gradually gained popularity in adult cardiac surgery and was subsequently adapted for adult hearts [29, 30]. Through its electrolyte composition, membrane stabilizers, and osmotic agents, the del Nido formulation limits calcium entry into myocardial cells during arrest and reperfusion, and consequently decreases the risk of myocardial stunning or necrosis [31]. This formulation is suitable for single-shot delivery and provides sufficient myocardial protection within a window for an aortic cross-clamping duration as long as 90 min [32]. Modified del Nido formulations were developed to better respond to adult heart demands, including different calcium handling (such as better sarcoplasmic reticulum function and higher baseline calcium stores), greater muscle mass, or often ischemic or hypertrophied myocardium. By increasing the blood content and decreasing the crystalloid portion, modified del Nido formulations increase oxygen delivery and help avoid hemodilution [33]. Some formulations have prolonged efficacy providing operational advantages in complex surgeries [34, 35]. Bloodless del Nido has emerged as an attractive cardioplegia alternative with combined advantages of inclusion of the key components in the crystalloid portion of del Nido and simplified delivery [12, 36].

The clinical outcomes associated with cardioplegia formulations have not been clearly established and depend on the complexity of the surgery and the experience of the surgical center.

A recent single-center phase 3 randomized controlled trial (RCT), which enrolled

226 participants undergoing elective coronary bypass grafting (CABG), valve

surgery, and/or aortic root surgeries, and compared Cardioplexol with Buckberg,

has indicated equivalent myocardial injury (peak 24-h troponin-T 0.77 vs 0.78

ng/mL), workflow advantages associated with faster arrest (11 s vs 71 s,

p

A strategic consideration in delivering cardioplegic solutions is the choice of temperature. Cold cardioplegia is most widely used and is delivered at 4–10 °C to provide strong metabolic suppression. Warm cardioplegia, known as normothermic cardioplegia, is delivered at 34–37 °C and is used for continuous perfusion. Tepid cardioplegia strikes a balance between the cold and warm strategies, and is delivered at 28–32 °C. The adequate temperature of cardioplegia solution might enhance tolerance to ischemia and is key to decreasing myocardial oxygen consumption need.

Although an early meta-analysis suggested that cold and warm blood cardioplegia are both safe and effective for myocardial protection, and that warm blood cardioplegia results in an improved cardiac index and lower enzyme release after surgery [44], solely temperature-based comparisons between strategies are implausible. Because of large variations in the compositions of cardioplegic formulations and delivery techniques, unequivocally defining the role of the delivery temperature remains difficult [21, 45].

Cardioplegia delivered via the aortic root into the coronary arteries, following the normal direction of blood flow, is known as anterograde cardioplegia. Advantages of anterograde delivery include operational simplicity and efficient delivery in normal coronary anatomy, thereby enabling uniform distribution of cardioplegia in non-obstructed vessels. Anterograde cardioplegia can be ineffective in distal to severe stenosis or occlusion and is inadequate in moderate or severe aortic regurgitation. Retrograde cardioplegia is administered via a catheter in the coronary sinus, thereby perfusing the venous side of the heart (opposite from normal flow), and it can bypass coronary obstructions and therefore is effective distal to blocked arteries. Retrograde cardioplegia provides uniform perfusion of the subendocardium (which is particularly vulnerable during ischemia) and can be administered continually during prolonged procedures. Retrograde cardioplegia is technically more challenging than anterograde cardioplegia. Moreover, it can result in inadequate right ventricle perfusion if it is positioned too distally in the coronary sinus, it poses risks of coronary sinus injury, and its effectiveness is diminished in patients with coronary sinus anomalies [46, 47]. Combined anterograde/retrograde delivery achieves more uniform cooling, with more favorable injury biomarker profiles and improved patient outcomes compared to anterograde alone [47, 48]. Table 2 summarizes the indications for various cardioplegia delivery procedures.

| Category | Description | Typical Use/Indications | Advantages | Limitations |

| Anterograde | Delivered forward through the aortic root or directly into coronary ostia | Aortic cross-clamp in place Normal/adequate coronary arteries CABG, valve surgery | Simple, physiologic coronary filling Rapid distribution | Less effective with severe coronary stenosis (compared to retrograde) |

| Potential for left ventricle distension due to aortic insufficiency | ||||

| Retrograde | Delivered backward via coronary sinus (right atrium) | Severe coronary artery diease Aortic regurgitation Re-operations with grafts |

Perfuses myocardium despite proximal coronary blockages Avoids aortic valve insufficiency issues |

Less effective for right ventricle and subendocardium (compared to anterograde) |

| Coronary sinus injury risk | ||||

| Combined | Uses both anterograde and retrograde routes | Complex cases Reintervention Hypertrophied hearts Long cross-clamp times | Ensures complete myocardial protection | More complex setup Longer delivery time (compared to anterograde or retrograde alone) |

| Overcomes limitations of each route alone |

CABG, Coronary artery bypass grafting.

Extensive efforts to optimize cardioplegia approaches led to the development of a multitude of protocols whose use varies across institutions and highly depends on surgeon preference and on-site resource availability. Simplicity of delivery and operational safety are major factors contributing to the decision. Limited large randomized clinical trials have evaluated and compared the efficacy of the wide variety of available cardioplegia protocols. The large body of information published to date has been based on retrospective studies and therefore provides low to moderate strength of evidence and limited guidance.

Despite advancements in myocardial protection, the available techniques have been demonstrated to provide limited efficacy in high-risk populations, specifically those with diabetes or left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), during cardiac surgery.

Diabetes is associated with elevated rates of postoperative complications and mortality after cardiac surgery, probably because of compromised microvascular integrity and suboptimal protection during ischemic arrest. The contributing mechanisms relate to endothelium-dependent and independent microvascular dysfunction, along with enhanced vascular permeability (“leakage” of molecules from blood vessels into surrounding tissue), oxidative stress, and apoptotic signaling. Cardiopulmonary bypass in patients with diabetes induces distinct transcriptional changes, particularly upregulation of inflammatory and apoptotic pathways (e.g., MYC, JUN, and IL-8) and downregulation of adherent-junction proteins; these factors together contribute to impaired myocardial resilience [49, 50, 51]. Early clinical trials indicated that infusion with glucose–insulin–potassium (GIK) before the onset of (cardiopulmonary bypass) CPB and immediately after aortic unclamping ameliorates myocardial function and accelerates recovery in patients with diabetes after CABG [52, 53, 54]. The rationale for GIK use is that it enhances metabolic support and decreases ischemic injury: glucose provides energy, insulin enhances glucose uptake, and potassium maintains ionic balance. In patients with diabetes, the glucose supplementation decreases levels of free fatty acids, which are responsible for arrhythmias and decreased myocardial performance. The insulin upregulates the L-arginine–nitric-oxide pathway, thus resulting in vasodilation and decreased vascular resistance, and further contributing to myocardial performance during reperfusion. In addition, insulin improves platelet function and helps prevent thrombotic complications. However, because inconsistent results have been reported over time, GIK therapy is not routinely used. To provide protective strategies for patients with diabetes, better understanding of the underlying pathophysiological mechanism leading to complications is crucial. For example, cardioplegia arrest and CPB significantly upregulate cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) gene/protein expression in the myocardium and coronary arterioles in the early post-CPB period. This process alters arteriole relaxation and is more pronounced in patients with uncontrolled diabetes than in those with controlled diabetes and individuals without diabetes [55]. These findings might provide future grounds for developing and applying tailored perioperative cardioprotective strategies in patients with diabetes.

Hearts with LVH are more susceptible to ischemic insults than normal hearts [56]. Structural imbalances in hypertrophied myocardium hinder the diffusion of oxygen and nutrients, according to hypertrophy severity. Decreased capillary density, arteriolar wall thickening, and increased microvasculature resistance all contribute to altering perfusion dynamics in LVH [57, 58, 59]. Therefore, cardioprotection for patients with LVH is challenging [56], and consensus is lacking regarding optimal strategies. Studies comparing anterograde vs. retrograde delivery, cold vs. warm cardioplegia, and hot-shot adjuncts have indicated inconsistent benefits in LVH, thereby reflecting uncertainty in protection efficacy [13, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65].

When exposed to brief ischemia periods, the heart responds and adapts through molecular defense mechanisms that decrease injury from subsequent ischemic events. This natural adaptive process is called ischemic preconditioning (IPC) [66]. Several strategies for perioperative myocardial protection have been designed to deliver IPC-like benefits.

Remote ischemic conditioning (RIC) is a non-invasive cardioprotective strategy in which brief, controlled episodes of ischemia and reperfusion are applied to a remote organ or tissue, usually a limb, to protect the heart (or other organs) against subsequent ischemia–reperfusion injury [67, 68]. RIC triggers protective signaling through humoral, neural, and systemic pathways affecting distant organs, and it may counteract oxidative stress and decrease pro-inflammatory biomarkers [69, 70]. In principle, RIC can be performed before anesthesia or surgery (preconditioning) or can be applied during or after ischemic insult (known as pre- or post-conditioning). RIC can have acute and delayed effects [71, 72]. RIC is justified by its physiological mechanism and proven safe. Although small clinical trials have indicated encouraging results, its clinical efficacy in decreasing myocardial injury remains uncertain [73, 74]. Large randomized clinical trials have not demonstrated that remote ischemic preconditioning (RIPC) attenuates myocardial injury. The RIPHeart trial, which randomized 1403 patients to upper limb RIPC (four sessions of 5 minutes blood-pressure cuff inflation, while patients were under propofol-induced anesthesia) or a sham treatment, found no significant differences between groups in troponin release [75], and no relevant benefits in decreasing the rates of primary composite endpoints or their individual components (death, myocardial infarction, stroke, and acute renal failure) until hospital discharge. The ERICCA trial also investigated the effect of upper limb RIPC under anesthesia in 1612 patients randomized to intervention or sham treatment, and found no significant between-group differences in perioperative myocardial injury, assessed according to high sensitivity troponin T release (area under the curve until 72 h postoperatively), inotrope scores (calculated from the maximum dose of the individual inotropic agents administered in the first 3 days after surgery), acute kidney injury, intensive care unit and hospital lengths of stay, 6-minute walk test distance, and quality of life [76]. The ERICCA trial found no benefits concerning the primary endpoint, or the rates of major adverse cardiac and cerebral events, assessed within 12 months after randomization. A more recent randomized controlled trial enrolled 509 patients at high risk of acute kidney injury and investigated the effects of RIPC performed 24 h before cardiac surgery. No significant between-group differences were observed in perioperative myocardial injury (assessed according to the concentrations of cardiac troponin T, creatine kinase myocardial isoenzyme, and N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide); intensive care unit and hospital lengths of stay; or occurrence of nonfatal myocardial infarction, stroke, or all-cause mortality by day 90 [71]. However, the occurrence of acute kidney injury was significantly lower in the RIPC group. The results to date regarding RIC efficacy remain uncertain. Optimization of RIC cycles regimens might warrant future RCT trials to obtain conclusive results.

Although pharmacologic adjuncts mimicking IPC have long been investigated, their translational value remains limited [1]. Volatile anesthetics, such as sevoflurane, isoflurane, and desflurane, have been shown to mimic the effects of IPC. Because they activate some of the same pathways as IPC, volatile anesthetics have been used before ischemia, as preconditioning agents, as well as during ischemia or early reperfusion, when they might offer preconditioning/postconditioning effects. The clinical benefits of volatile anesthetics remain uncertain [77, 78, 79].

Metabolic modulation therapy is designed to decrease oxidative stress during

ischemia through alternative or concomitant pathways. These pathways consist of

directly enhancing glucose oxidation; decreasing circulating levels of fatty

acids and/or their uptake by cardiac myocytes or mitochondria; and directly

inhibiting the enzymes participating in fatty acid oxidation [80]. Among cardiac

modulator drugs, trimetazidine (TMZ) has been extensively investigated. TMZ

inhibits the mitochondrial enzyme 3-ketoacyl CoA thiolase, thereby decreasing

fatty acid

The mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) is a central target in IPC. Cyclosporine A (CsA), an inhibitor of mPTP opening, has shown promise in experimental models of ischemia–reperfusion injury and in small clinical studies. However, CsA has shown limited or inconclusive evidence in clinical trials, partly because of the action of propofol as an inhibitor of mitochondrial signaling, as well as attenuated responsiveness in the context of the comorbidity burden in patients with cardiac conditions. In addition, safety concerns (nephrotoxicity, hypertension, and neurotoxicity), particularly in older people, even at the low doses required for cardiac protection, prevent the routine use of CsA in the context of cardiac surgery [85].

Acadesine, also known as 5aminoimidazole4carboxamide riboside or AICAR, is a prominent adenosine-regulating conditioning mimetic whose relevance for IPC has been investigated. It acts as an AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) agonist, by enhancing glucose uptake and mitochondrial protection [86, 87]. Despite being demonstrated to be safe, acadesine has not shown clinical benefits in large, phase III trials and is not used in cardiac surgery [88].

Perioperative ischemia often occurs silently and is biochemically confirmed only hours after it occurs [89]. The gold standard for assessing perioperative myocardial injury is treatment with cardiac troponins I and T (cTns, cTnI, and cTnT), which reflect myocardial cell injury from surgical manipulations and myocardial stunning or necrosis. The timing and height of the troponin peak reflect injury severity and help differentiate reversible stress from necrosis or infarction. Typically, a sustained peak within 12–24 h post-surgery is considered indicative of severe injury. Another clinical marker of myocardial injury is the creatine kinase (CK)-MB fraction. This hybrid isoenzyme is abundant in cardiac muscles and is released into the blood when cardiomyocytes are injured [90]. CK-MB can be used for perioperative monitoring. Serial measurements enable prediction of infarct size and tracking of myocardial injury timing and resolution. CK-MB levels rise 3–12 h after injury, peak around 24 h, and return to normal within 48–72 h. Because CK-MB is also found in skeletal muscle, elevated CK-MB levels also reflect muscle damage after sternotomy. The ratio between CK-MB and CK total (a biomarker which sums heart, muscle, and brain injuries) can help determine whether chest pain is associated with myocardial infarction. For detecting small ischemic areas, CK-MB is less sensitive than troponins I and T, which are cardiac specific. N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide, which peaks after 24 h (within 1–2 days after surgery), provides complementary information regarding ventricular stress and risk, particularly in patients with left ventricular (LV) dysfunction or comorbidities.

Electrocardiography (ECG) is used to monitor rhythm disturbances before and after CPB. ECG’s sensitivity for detecting myocardial ischemia can be masked by anesthesia, hypothermia, and non-specific inflammatory reactions secondary to cardiac trauma; moreover, ECG results are best used in conjunction with biomarker and echocardiography findings [91]. Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) can detect ischemia through regional wall motion abnormalities, with high sensitivity and specificity. The limitations of TEE include that it can miss subtle or diffuse ischemia, and it depends strongly on operator skill [91, 92]. Other modalities, such as hemodynamic and clinical monitoring, are non-specific and usually indicate consequences of injury rather than the injury itself.

Currently, the modalities available in clinical practice can detect perioperative myocardial injury only after it has occurred. A critical gap is the lack of early, real-time detection, which would facilitate adjustment of protective strategies and implementation of early interventions. This need is increasingly being addressed by experimental technologies such as pH sensors, coronary sinus sampling, and rapid biomarker assays.

Myocardial temperature probes are widely commercially available and are used in routine practice in many centers. These probes are commonly inserted in the left ventricle free wall and are used to guide cold cardioplegia delivery. A premature rise in temperature during cardioplegic arrest can inform re-dosing and decrease the risk of insufficient myocardial protection. In addition, temperature monitoring can help ensure complete and uniform re-warming during un-clamping [93]. In contrast to the advances in temperature monitoring, intraoperative myocardial pH sensor technology has been insufficiently developed, despite its potential practical utility. Under hypoxic conditions, cardiomyocytes switch to anaerobic glycolysis. This metabolic change results in the production of lactic acid, which is broken into lactate and hydrogen ions, thereby decreasing the pH. Ischemic acidosis, the earliest metabolic signal of inadequate myocardial protection, can be sensed with glass-made, needle-tip intramyocardial pH electrodes placed in the anterior and posterior LV walls [94, 95]. More recently, fluorescent fiber-optic probes have been explored as a more durable and flexible alternative [96]. A decrease below pH 7 is generally considered a reliable threshold for irreversible injury, and, when coupled with temperature measurements, serves as an intraoperative indicator for optimizing cardioplegia and reperfusion [94, 95]. Myocardial acidosis, determined intraoperatively with locally inserted pH probes, has been associated with adverse outcomes and increased postoperative health care costs in observational studies [97, 98, 99, 100]. Evidence from randomized clinical trials is lacking, and pH sensor technology remains largely limited to research purposes. Very limited myocardial pH monitoring systems have received regulatory clearance for use in humans and are commercially available. Clinical translational challenges stem from operational hurdles associated with the probe’s invasive nature and fragility; limitations associated with tissue heterogeneity and the need to insert two or more electrodes in the myocardium to map the acidosis; the need for frequent calibration to compensate for temperature drift and maintain measurement accuracy; and the lack of standardization of pH cutoff values for interventions in humans. Alternatively, because bicarbonate buffering produces carbon dioxide in acidic, hypoxic conditions, pCO2 sensors, both conductometric and fiber-optic, have been proposed for continuous myocardial monitoring [101].

Coronary sinus metabolite sampling is used to directly assess myocardial metabolism and ischemic stress by intermittently or continually analyzing the chemical composition of blood draining from the coronary circulation during early reperfusion and post CPB. Commonly measured parameters include lactate, acidosis, O2 content, glucose, potassium, creatine kinase, troponin [102, 103, 104, 105, 106]. Because the technique is invasive and technically demanding (requiring retrograde catheterization and guidance with TEE or fluoroscopy), and in the absence of widely used clinical guidelines and thresholds for interpreting coronary sinus metabolite levels intraoperatively, coronary sinus sampling is not used beyond research settings or high-risk cardiac surgeries for complex cases with suspected regional ischemia. Other biomarkers of myocardial injury have shown promise, although their intraoperative use is limited by the lack of real-time analysis assays (and therefore require long laboratory processing times and lack of point-of-care availability). One such biomarker, heart-type fatty acid-binding protein (h-FABP), is rapidly released into the bloodstream when myocardial injury occurs (e.g., ischemia/reperfusion), often within 30 minutes [89, 107]. This protein reflects early, reversible damage to the myocardium, and the intraoperative thresholds clinically relevant for adjusting interventions are highly unclear. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) have potential to be used analogously to coronary sinus metabolite sampling. miR-1, miR-133a, miR-208a, and miR-499 are released by cardiomyocytes during ischemia, reperfusion, or mechanical stress, and their levels rise earlier than troponin [108, 109]. The intraoperative use of miRNA biomarkers is impeded primarily by the lack of assays at the point-of-care.

The “holy grail” in perioperative myocardial protection is patient tailored cardioplegia, in which the cardioplegic formulation composition, amount, and dosing time are adjusted to each patient’s myocardial needs. Development of next-generation cardioplegia could extend protection duration beyond 90 minutes without re-dosing, minimize cellular injury at reperfusion, decrease inflammation and oxidative stress, and provide intraoperative feedback to facilitate personalized adjustments. Because the timing of myocardial injury evaluation is highly important, a shift toward real-time intraoperative monitoring could enable preventive measures. Depending on severity, the reversible phase of the injury (pre-necrosis) lasts minutes to hours—the optimal window of opportunity for interventions enabling myocyte recovery and preservation of contractile function. After necrosis, which is marked by a rise in troponins, the cardiomyocyte membranes rupture, and the damage becomes permanent. Intervention before irreversible injury can comprise timely re-dosing of cardioplegia; switching to retrograde cardioplegia if anterograde flow is blocked; or adjustment of cardioplegia temperature, formulation composition, or pressure. Detection of ischemia during reperfusion could support decisions regarding adjusting the reperfusion rate to decrease oxidative stress, administering antioxidants (e.g., vitamin C or N-acetylcysteine), or adding vasodilators or nitric oxide donors to support perfusion. Regional dysfunction (e.g., indicated by accelerometers) could guide perfusion pressure optimization, targeted coronary perfusion, or early revascularization.

As new myocardial protection approaches emerge, achieving standardization across institutions and defining strategies for specific patient populations must be encouraged. Artificial intelligence (AI) can be leveraged to predict perioperative myocardial injury risk [110, 111]. When integrated with preoperative diagnostics and intraoperative monitoring of cardiac temperature, pH, and myocardial injury biomarkers, AI algorithms can facilitate risk prediction to optimize surgical planning and increase patient safety, as well as the choice of cardioplegic formulation composition, delivery route, and volume and anticipated frequency of re-dosing, according to patient physiology. When combined with automated surveillance of intraoperative parameters, AI models predicting myocardial injury would help improve operational flow, by alerting surgeons and perfusionists regarding the need for cardioplegia re-dosing while avoiding unnecessary interruptions. Advances have been made in the field of hemodynamic monitoring and cardiac surgery planning. Because of limited intraoperative data capture possibilities, AI supported approaches for improved intraoperative myocardial protection strategies are not yet available [112, 113, 114, 115].

Genetic and epigenetic mechanisms are increasingly recognized to be key determinants of how patients respond to ischemia and myocardial protection during cardiac surgery [116, 117, 118]. Emerging evidence might enable the evaluation of new therapeutic targets for decreasing myocardial injury and performing risk stratification for cardioprotection strategies designed to lower complication rates and improve patient outcomes. Clinical evidence must be based on rigorously designed randomized clinical trials, and must focus on not only short-term endpoints (e.g., troponin levels and ICU length of stay) but also long-term ventricular function, quality of life, or survival associated with intraoperative protection strategies. Stronger collaborative networks should enable the development and delivery of improved guidelines for perioperative myocardial protection.

Despite decades of clinical use, myocardial protection strategies in cardiac surgery remain highly variable, limited comparative evidence is available, and suboptimal outcomes have been observed in high-risk populations such as patients with diabetes or LV hypertrophy. Pharmacologic adjuncts and remote ischemic conditioning have shown limited clinical success, and a critical need exists for real-time intraoperative monitoring to detect myocardial injury.

Emerging tools, such as pH sensors and coronary sinus biomarker sampling, offer promise but require further validation and standardization. Personalized protection strategies tailored to patient-specific physiology and comorbidities, supported by AI and robust clinical trials, are potential future directions. Standardization, innovation, and stronger evidence will be key to advancing myocardial protection and improving patient outcomes.

DDL, MC designed the study. DDL, AH, GZ, JJ performed literature search and data extraction. AH, CH, MC provided expert advice and validated the ideas outlined in the manuscript. DDL and MC wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.