1 Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, 610000 Chengdu, Sichuan, China

2 West China School of Nursing, Sichuan University, 610000 Chengdu, Sichuan, China

3 Department of Cardiovascular Surgery and National Clinical Research Center for Geriatrics, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, 610000 Chengdu, Sichuan, China

4 Integrated Care Management Center, Outpatient Department West China Hospital, Sichuan University, 610000 Chengdu, Sichuan, China

5 Outpatient Department, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, 610000 Chengdu, Sichuan, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Takayasu arteritis (TAK), a chronic inflammatory condition often leading to aortic dilation and regurgitation (AR), poses significant surgical challenges due to vascular fragility and calcification, increasing risks of complications. For high-risk TAK patients with severe AR, transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) may be a viable alternative.

A 49-year-old woman with TAK presented with severe AR, porcelain aorta, and aortic branch malformation. She successfully underwent transapical TAVR with a 25 mm J-valve. Post-procedural follow-up at two years showed notable improvement in left ventricular dimensions and ejection fraction.

TAVR with the J-valve appears to be an effective and safe treatment for high-risk TAK patients with severe AR and porcelain aorta, providing satisfactory mid-term outcomes. This minimally invasive approach represents a valuable option when surgery is contraindicated due to anatomical complexity and tissue fragility.

Keywords

- aortic regurgitation

- Takayasu arteritis

- transcatheter valve aortic replacement

- transapical

Takayasu arteritis (TAK) is a chronic inflammatory disease that primarily affects the aorta and its main branches. TAK predominantly affects young women. Moreover, some TAK patients develop aortic dilation, which can lead to aortic regurgitation (AR). The optimal therapeutic strategy for TAK patients with AR remains controversial. A prior study showed that surgical treatment for TAK patients with AR provided a better prognosis compared to those treated with medications only [1]. However, surgery for TAK patients with AR presents various challenges. Inflammatory conditions may increase the difficulty in suturing tissues and replacing the aortic valve, potentially leading to adverse postoperative complications, including pseudo-aneurysms, valve and suture line detachment, and paravalvular leakage (PVL) [2]. Additionally, the risk of vascular complications (e.g., aortic dissection or aortic rupture) is relatively high in TAK patients with diffuse calcification in the aorta or so-called “porcelain aorta”. Thus, transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) may be a suitable approach. This study aimed to discuss the efficacy and safety of TAVR implantation using the J-valve.

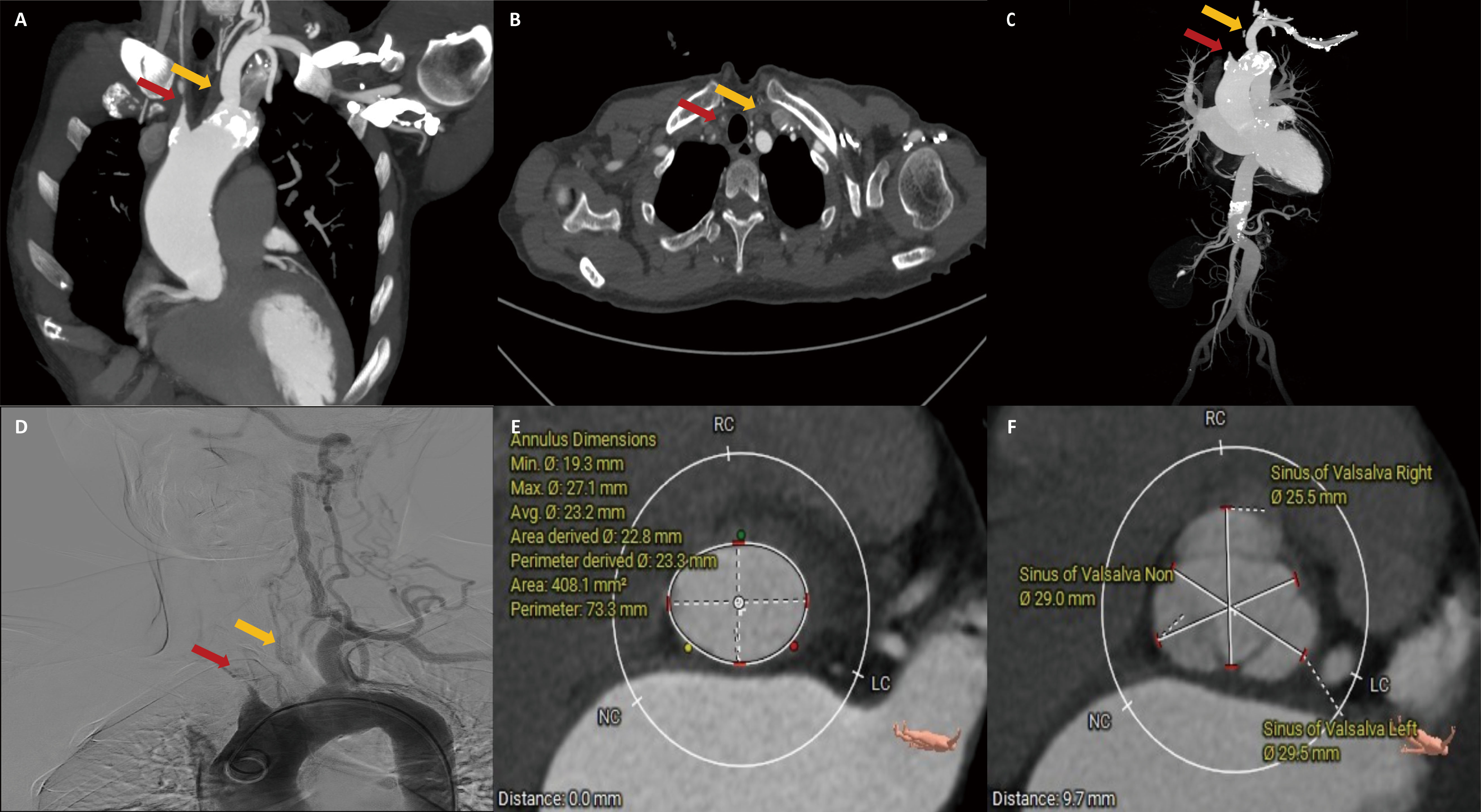

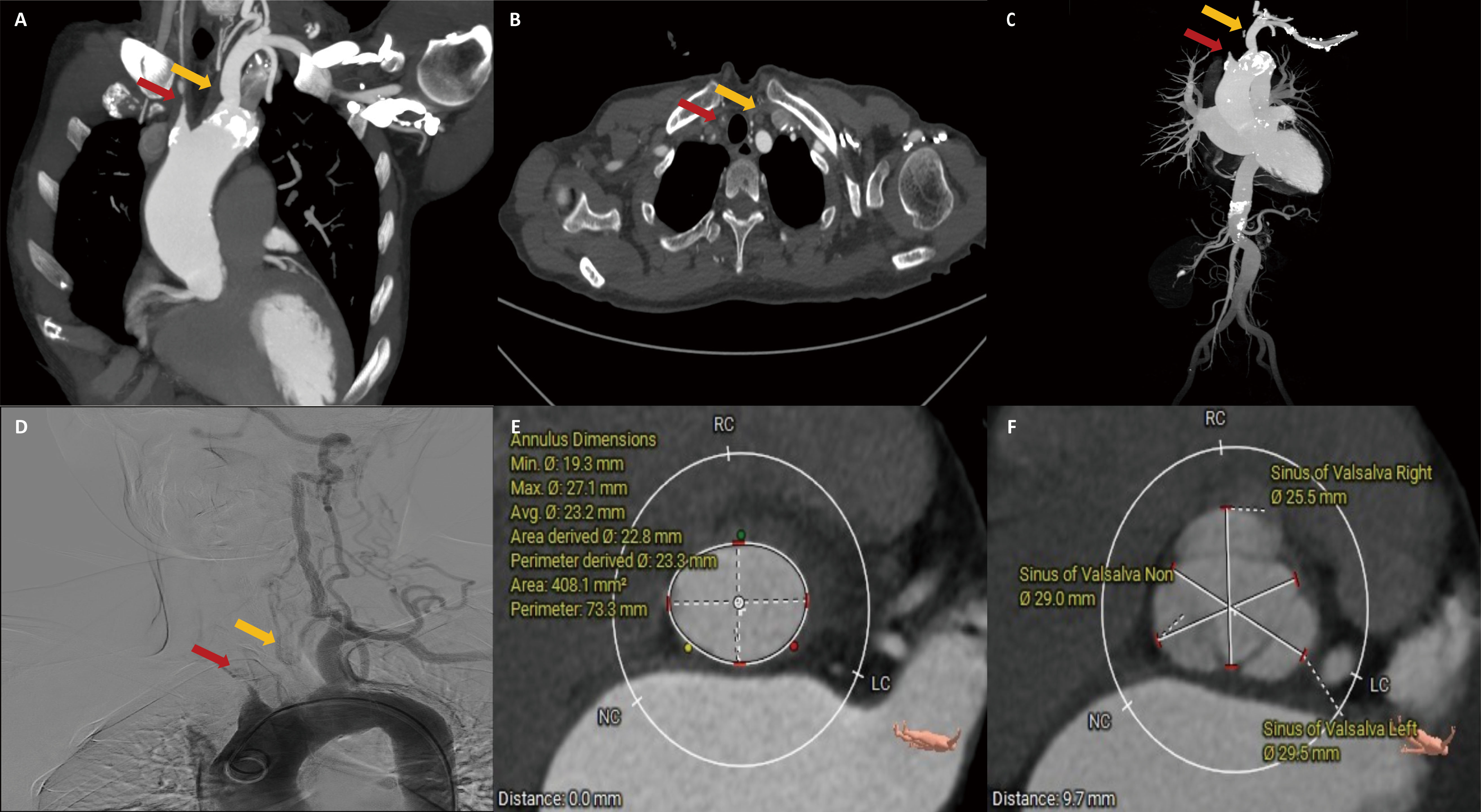

A 49-year-old female presented with a one-month history of post-exercise chest tightness and cough. The patient had a headache and dizziness and had previously been diagnosed with TAK two years ago. The systolic blood pressure of the patient was 140 mmHg in the left upper limb and 123 mmHg in the right upper limb. Computed tomography (CT) revealed varying degrees of calcification and stenosis in the aortic arch and its branches (Fig. 1A–C). Vascular ultrasound indicated severe stenosis in both the right common carotid and subclavian arteries. Angiography revealed occlusion of the brachiocephalic trunk and left common carotid artery, with only the left subclavian and left vertebral arteries visible (Fig. 1D). Echocardiography showed severe AR and mitral regurgitation (MR) (Fig. 2A), with the left ventricular measuring 53 mm and a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 38% (Table 1). Both the ascending aorta and pulmonary artery were also enlarged.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Computed tomography and angiography. (A–C) Aortic arch and branching vessels morphology. (D) Angiography. (E) Aortic valve annulus plane measurement. (F) Sinus of Valsalva plane measurement. The red arrow represents the right common carotid artery, and the yellow arrow represents the left common carotid artery.

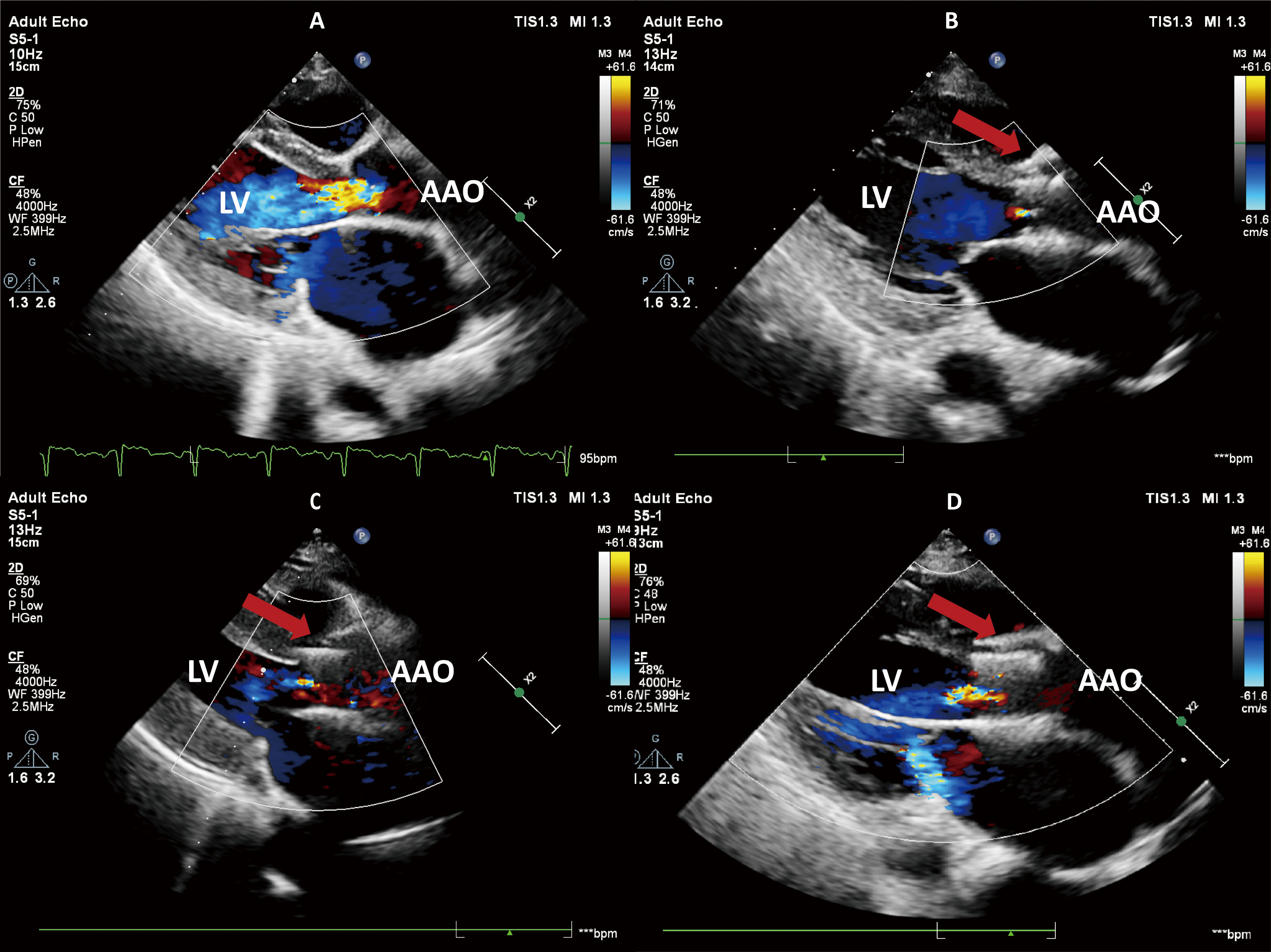

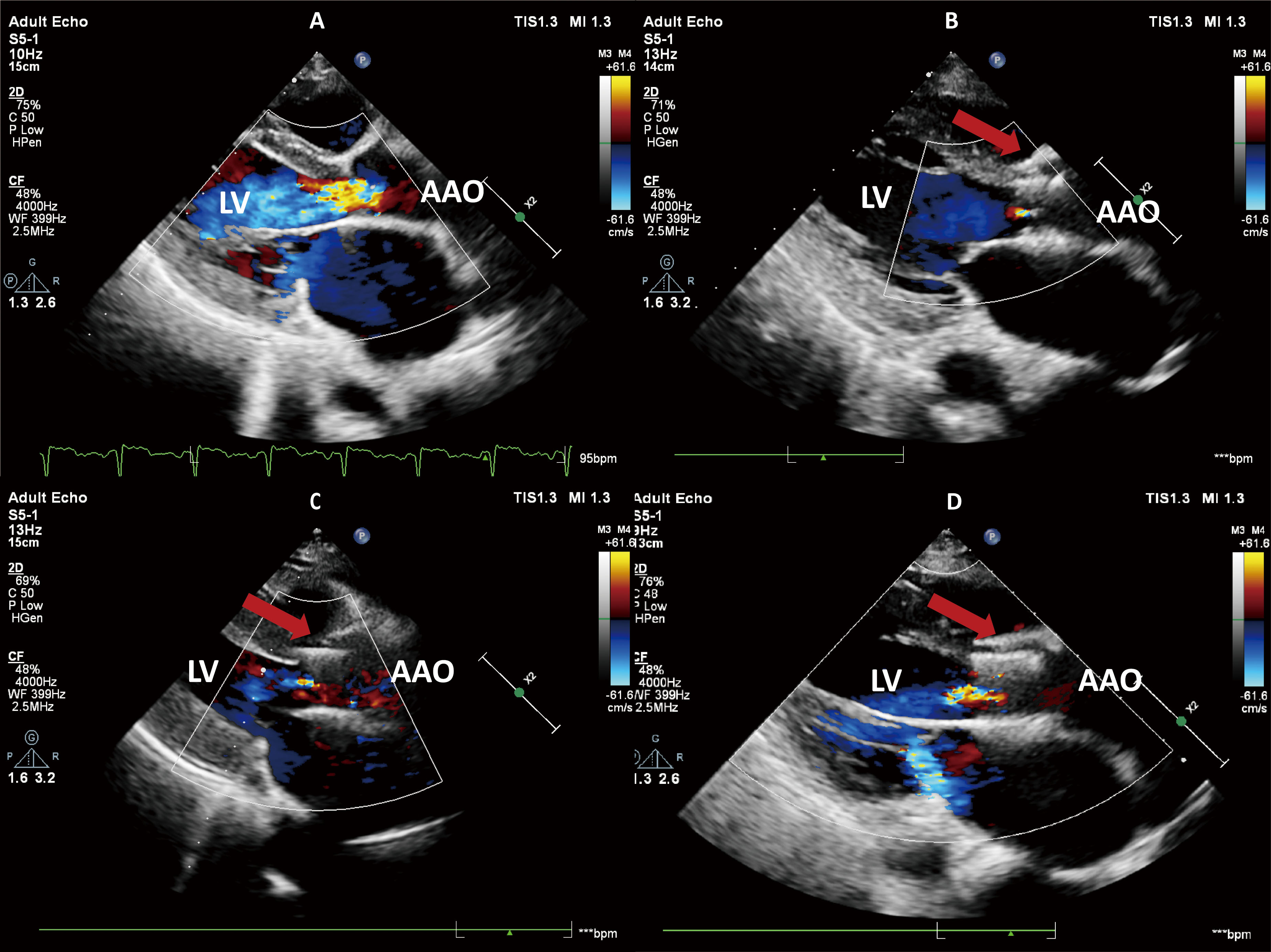

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Transthoracic echocardiography. (A) Preoperative echocardiography revealed severe aortic regurgitation. (B) The echocardiogram on the third day after surgery showed that the aortic regurgitation had disappeared. (C) One year after the surgery, echocardiography demonstrated trivial aortic regurgitation. (D) Two years after the surgery, echocardiography demonstrated mild aortic regurgitation. The red arrow represents the prosthetic valve. LV, left ventricular; AAO, ascending aorta.

| Time schedule | LVEF | AVmax | Pressure gradient | LV | LA | MR | PVL | TAR | KCCQ-12 | NYHA |

| 2023-02-15 (preoperative) | 38 | 1.3 | NA | 53 | 55 | Severe | NA | NA | 63.54 | IV |

| 2023-02-27 (postoperative) | 35 | 1.5 | NA | 55 | 45 | Trivial | None | None | NA | III |

| 2023-03-01 (1-month) | 38 | 1.8 | 7 | 53 | 41 | Trivial | None | None | 57.81 | III |

| 2023-05-30 (3-month) | 46 | 2.3 | 11 | 47 | 36 | Trivial | None | Trivial | NA | II |

| 2024-01-30 (1-year) | 52 | 2.4 | 13 | 44 | 37 | Trivial | None | Trivial | 92.19 | II |

| 2025-03-15 (2-year) | 53 | 2.9 | 18 | 51 | 39 | Mild | Trivial | Mild | 88.54 | I |

LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; AVmax, aortic valve maximum velocity; LV, left ventricle; LA, left atrium; MR, mitral regurgitation; PVL, paravalvular leak; TAR, transvalvular aortic regurgitation; KCCQ-12, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire Clinical Summary Score; NYHA, New York Heart Association Functional Classification; NA, not applicable.

The CT measurement of the aortic valve annulus diameter ranged from 22.8 to 23.3 mm, prompting the selection of a 25 mm J-valve (an oversized rate of 8%), which is slightly larger than the native aortic valve annulus (Fig. 1E,F). The patient underwent transapical TAVR and used a 25 mm J-Valve (Fig. 3; Video 1). Severe AR was observed before valve deployment and disappeared after valve deployment.

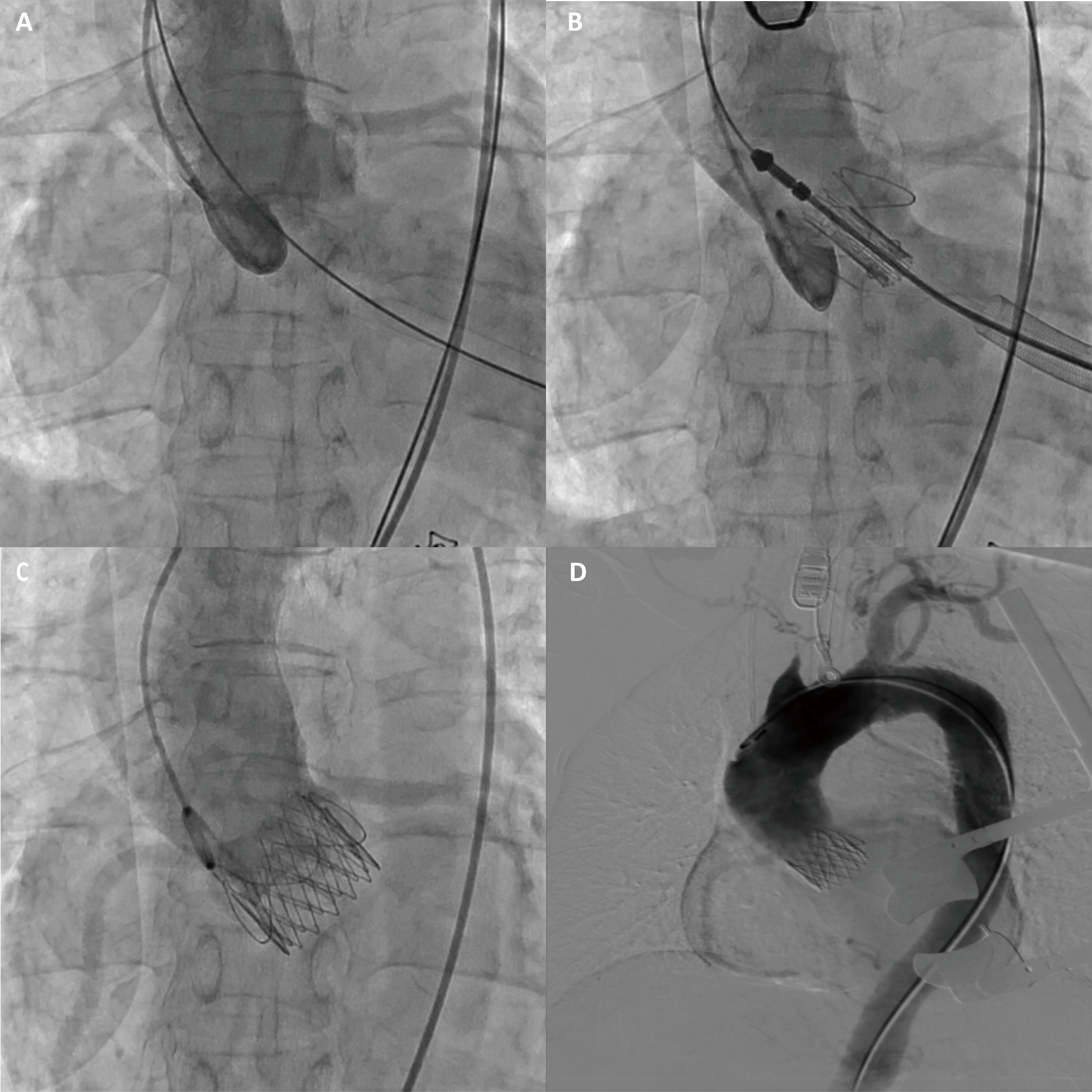

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

The J-valve implantation procedure. (A) Aortic root angiography shows severe aortic regurgitation. (B) Aortic root angiography shows that the J-valve is located in the annular plane. (C) After the J-valve release, aortic root angiography was performed again and showed no regurgitation. (D) Aortic angiography showed no evidence of aortic dissection or vascular rupture.

The J-valve implantation procedure. Video associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/HSF48343.

The patient was diagnosed with TAK two years prior to re-admission and had been undergoing long-term treatment with 2.5 mg of prednisone orally once daily, 500 mg of mycophenolate mofetil orally twice daily, and dual antiplatelet therapy. Before surgery, the patient was in a stable phase of the disease. The C-reactive protein (CRP) level was 6.13 mg/L, procalcitonin (PCT) was 0.04 ng/mL, and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 11.0 mm/h. On the day of surgery, an additional dose of 20 mg of methylprednisolone was administered intravenously, and mycophenolate mofetil was discontinued for two weeks. Postoperatively, 10 mg of prednisone was continually administered orally once dailyfor two weeks, with adjustments made based on CRP, PCT levels, and signs of infection. During this period, the patient did not exhibit significant inflammatory reactions or signs of infection. Therefore, the previous medication regimen was resumed after two weeks.

Three-day post-procedural echocardiography showed no AR and trivial MR (Fig. 2B). At the one-year follow-up, trivial TAR and MR were observed (Fig. 2C), and the LVEF improved to 52%. During the 2-year follow-up, no valve leaflet thrombosis or displacement was observed with the prosthetic valve. However, there was a trend toward increased forward blood flow, accompanied by minimal paravalvular leak (PVL), mild transvalvular regurgitation (TAR), and mild MR (Fig. 2D). Compared to the first-year echocardiogram, the left ventricular and left atrial diameters in the patient increased to varying degrees, potentially related to the presence of mild valve regurgitation (Table 1). Throughout the follow-up, the patient did not experience adverse events, such as rehospitalization due to heart failure or stroke. At 49 months post-operation, the patient developed third-degree atrioventricular block and was implanted with a permanent pacemaker.

TAK is a chronic inflammatory arterial disease primarily affecting the great arteries and their major branches, predominantly in Asian women [3]. Typically, TAK involves the aortic root and may affect the aortic valve leaflets, potentially leading to AR. Ergi DG et al. [4] investigated 17 patients with TAK who underwent aortic valve replacement surgery and found that two cases (11.7%) developed active valvulitis. One patient presented with focal valvulitis characterized by mixed inflammation consistent with aortic inflammation, while the other exhibited minimally active chronic valvulitis with fibrotic thickening [4]. The inflammation associated with TAK may directly impair aortic valve function by damaging its structural integrity. The incidence of AR in TAK patients ranges from 13% to 25% [2]. Chronic AR can lead to left ventricular volume overload, which triggers progressive left ventricular dilatation and eccentric hypertrophy, ultimately resulting in heart failure. In a study by Cheng et al. [1], left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD) was identified as a significant prognostic factor for long-term outcomes in TAK patients; for every 1 mm increase in LVEDD, the risk of composite endpoints increased by 3.6%. Active treatment should be initiated for patients with aortic valve involvement in the context of TAK to prevent further deterioration of cardiac function. However, due to chronic inflammation causing fragility of the aortic valve annulus and vascular wall tissue, these cases carry a high risk of postoperative prosthetic valve detachment or aneurysm formation at the anastomosis site, leading to poor clinical outcomes [2]. Zhang et al. [5] investigated patients with TAK who underwent cardiac surgery, finding that during a median follow-up of six years, among 23 patients who underwent aortic valve replacement, 10 composite adverse events occurred (including death, reoperations, residual ascending aortic aneurysms, paravalvular leaks, and valve detachment). Multiple studies have confirmed that inflammatory markers, such as ESR and CRP, are elevated in TAK patients with aortic valve involvement, and the levels of inflammation are closely associated with cardiovascular events [6]. Controlling inflammation is crucial for the progression and prognosis of TAK [7]. Patients with TAK should undergo surgical treatment during the stable phase [8]. Active postoperative control of inflammation is essential for preventing complications, such as prosthetic valve detachment and aneurysms at the anastomotic site [5, 7]. Therefore, the key to avoiding life-threatening complications in TAK patients with concomitant aortic valve disease lies in “no procedure” on the aortic valve annulus or vascular wall [9], combined with active anti-inflammatory therapy post-surgery.

The advent of TAVR technology has enabled “no procedure” on the aortic valve

annulus and vascular wall. Although it is primarily used for patients with

moderate to high surgical risk of aortic stenosis (AS) [10], the anatomical

differences between AS and AR present challenges when using transcatheter heart

valve (THV) devices designed for AS to treat AR. First, insufficient aortic valve

calcification often complicates the anchoring process. Second, AR is frequently

accompanied by aortic root disease, which complicates the procedure. Finally, the

“venturi effect” caused by regurgitation may lead to valve displacement or

embolism following implantation or expansion. In recent years, several

researchers have attempted to use off-label THV to treat AR, but the results have

been limited. In 2017, the ARTAVR registry reported a device implantation success

rate of 81.1% in AR patients treated with contemporary THVs, with a moderate or

greater PVL incidence of 9.6% and a 1-year all-cause mortality rate of 24.1%

[11]. In 2023, the PANTHEON study reported results for a new-generation THV

device in the treatment of AR. The device implantation success rate was 83.6%,

the incidence of

In our clinical practice, the preoperative assessment of disease activity is a standard component of the examination. This assessment includes a comprehensive evaluation of clinical symptoms, such as lameness and systemic manifestations, alongside biochemical monitoring of CRP, ESR, and PCT. Imaging studies, such as CT, are also employed to identify concomitant conditions. If evidence indicates active disease, treatment with corticosteroids, primarily prednisone, is initiated. Furthermore, the dosage may be adjusted, or immunosuppressive agents, such as mycophenolate mofetil or infliximab, may be introduced based on the response of the patient to steroid therapy. Anti-inflammatory treatment is typically sustained for 4 to 6 months in cases of active disease, after which surgery may be considered once disease activity has subsided [4]. Close follow-up is essential, as patients may experience recurrence or exacerbation of disease activity. Clinical, biochemical, and imaging assessments are recommended every 3 to 6 months to ensure that disease activity can be continuously monitored and immunosuppressive therapy adjusted accordingly.

Compared to traditional aortic valve replacement surgery, TAVR can be performed with minimal tissue suturing and aortic clamping, resulting in significantly reduced procedure times. Although a recent study found no direct evidence linking long operation time to poor patient outcomes, death occurred in TAK patients with an above-average surgery time. Both transapical (TA) and transfemoral (TF) access can be used for TAVR. In patients with porcelain aorta, TF-TAVR is associated with a higher risk of stroke [16]. Therefore, in this case, due to the aortic branch malformation and the right brachiocephalic trunk obstruction in the patient, TA access was chosen to minimize the risk of stroke. Only a few cases have reported outcomes of TA-TAVR in TAK patients with AR [9, 17]. We report, for the first time, the long-term outcomes of TAK patients with concomitant AR treated with the J-valve. The results indicate that the J-valve can provide an alternative treatment option for TAK patients with concomitant AR, particularly those at higher risk. Following J-valve implantation, patients experienced immediate improvements in AR and MR, accompanied by reductions in left ventricular and left atrial diameters. No serious cardiovascular adverse events were observed during follow-up, and heart failure symptoms improved significantly, as evidenced by an increase in the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ-12) score from 63.54 at baseline to 88.54 two years post-surgery, and a reduction in NYHA class from IV to I. Echocardiography at two years post-surgery showed good valve function, with the LVEF improving from 38% at baseline to 53% at the two-year mark. The patient did not experience any rehospitalizations due to heart failure. However, we noted an intriguing phenomenon: the blood flow velocity and mean transvalvular pressure gradient at the implanted prosthetic valve continued to increase, and mild MR was detected. Importantly, echocardiography did not reveal any valve leaflet thickening, thrombus, or displacement. Consequently, the previously reduced left ventricle began to enlarge again. The patient currently remains on long-term immunosuppressive therapy, with inflammatory markers indicating a stable condition. No symptoms of heart failure existed, and the test results suggested that surgical intervention was not required. We speculate that immune dysfunction and progressive inflammation may continue to impact the artificial valve [6]. Therefore, closer follow-up is necessary to assess the condition of the prosthetic valve.

Our experience suggests that TAVR may be a viable therapeutic strategy for patients with AR who are also receiving TAK.

Data is accessible through our system at our institution and is not publicly available.

BYL and YHL contributed to the study conception and design, as well as the writing and critical revision of the manuscript. SYH, YQW and TQC were responsible for the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data and image collection. They also participated in drafting and critically reviewing the manuscript. DJ and YQG contributed to data interpretation, manuscript revision, and provided administrative support. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The Biomedical Ethics Committee of West China Hospital of Sichuan University has waived this requirement for our case report. Based on the patient’s enrollment in the West China-VHD Registry (Registration No. 20232422), which has obtained ethical approval, and the patient’s consent for the use of medical records for research publication, this study qualifies for ethical exemption. The corresponding exemption approval number is 20232422. Consent for publication was obtained directly from the patient. The patient has agreed to the publication of her photo and medical records in the journal. She has read the manuscript or understood a general description of its contents and has reviewed all photographs, illustrations, videos, or audio files (if applicable) related to her for publication. The patient is aware that her name will not be published, and that articles published in the case report may be republished in other media and freely redistributed for any lawful purpose, including academic exchange, translation, and commercial use.

Not applicable.

This manuscript was supported by National Clinical Research Center for Geriatrics, West China Hospital, Sichuan University (No. Z2024YY001) and 1.3.5 project for disciplines of excellence from West China Hospital of Sichuan University (No. ZYGD22010).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/HSF48343.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.