1 Division of Cardiac Surgery, Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 15213, USA

2 Heart and Vascular Institute, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, PA 15213, USA

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Home health care (HHC) may help reduce the burden on patients and families after interventions and potentially reduce hospital length of stay (LOS). This study aimed to assess the outcomes of patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) who were discharged with or without HHC services.

This retrospective analysis utilized the Nationwide Readmissions Database (NRD) to identify TAVR patients (2010–2018) who were categorized based on discharge disposition into either the HHC cohort or the routine cohort. Propensity-matched outcomes are reported. Additionally, a multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to examine the 30-day readmission rate.

A total of 94,491 patients undergoing TAVR were included; 66.9% were routinely discharged, while 33.1% were discharged with HHC. The median age was higher in the HHC cohort (83.0 vs. 81.0 years; p < 0.01), which also comprised a greater proportion of women (48.7% vs. 41.8%; p < 0.01). After propensity matching, the LOS was longer in the HHC cohort (4.0 days [2.0–7.0] vs. 3.0 days [2.0–5.0]; p < 0.01). The 30-day readmission rate (19.9% vs. 15.8%; p < 0.01) and mortality rate (0.4% vs. 0.3%; p < 0.01) also remained higher in the HHC cohort. In the logistic regression analysis, the HHC status (odds ratio (OR): 1.34 [95% confidence interval (CI): 1.30–1.38]; p < 0.01), myocardial infarction (MI) (1.24 [1.15–1.33]; p < 0.01), paraplegia (2.10 [1.30–3.39]; p < 0.01), bowel ischemia (1.42 [1.07–1.88]; p = 0.02), and acute kidney injury (1.27 [1.22–1.33]; p < 0.01) were associated with 30-day readmission.

In conclusion, post-TAVR utilization of HHC services was associated with higher in-hospital complications and increased odds of 30-day readmissions. Thus, optimizing procedures for routine discharge and refining the criteria for HHC may help improve outcomes.

Keywords

- home health care

- transcatheter aortic valve replacement

- TAVR

The introduction of transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) has transformed the treatment landscape of aortic stenosis (AS), broadening the range of patients suitable for aortic valve replacement. Empirical evidence strongly backs the utilization of TAVR in a variety of clinical scenarios, with large analyses reporting minimal complication rates and decreased hospital readmissions post-TAVR [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]. To further improve rates of morbidities and readmissions after cardiac procedures, home health care (HHC) has been proposed as a form of home-based care aimed to better facilitate patients’ postoperative transition to a more bolstering home environment [7, 8]. However, evidence regarding the associated benefits of HHC remains unclear. Broadly, HHC has been applied in the setting of mitral valve repair and heart failure optimization, with mainly sobering results of higher association with hospital readmissions in the short term [9, 10, 11]. Previous reports have shown similar findings in the post-procedural period following TAVR, with higher rates of heart failure-specific and all-cause hospital readmissions [12]. More comprehensive evidence regarding the utility of HHC following TAVR is lacking. This study aims to compare post-TAVR outcomes in patients receiving HHC compared to routine discharges, while also identifying predictors and clinical outcomes associated with post-TAVR hospital readmission.

This observational study utilized the Nationwide Readmissions Database (NRD), a publicly available database of all-payer hospital inpatient stays. The NRD is part of a group of national databases developed for the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). The NRD includes more than 18 million discharges per year across 30 states, accounting for 61.8% of the total population of the United States and 60.4% of all hospitalizations. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pittsburgh on 4/17/2019 (STUDY18120143), and the research team completed relevant HCUP training modules and signed the NRD Data Use Agreement. Informed consent was not applicable as the data was obtained through the NRD.

This study aimed to compare TAVR outcomes between patients who received home health care (HHC) versus those who underwent routine discharge between 2010 and 2018. All patients undergoing “TAVR” were isolated, and data were extracted. These patients were identified by using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) and the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10), depending on the year of procedure. Codes 3505 and 3506 were used to identify TAVR patients with ICD-9 codes, while codes 02RF37Z, 02RF38Z, 02RF3JZ, 02RF3KZ, X2RF332, 02RF37H, 02RF38H, 02RF38H, 02RF3JH, and 02RF3KH were used to identify patients with ICD-10 codes. Discharge to home with HHC was defined as discharge to a private residence accompanied by services provided by either (1) an organized home health agency or (2) a home intravenous therapy provider. The specific nature of HHC was determined by the individual protocols and practices of each provider agency. For analytic purposes, discharge disposition was dichotomized into two groups: (1) routine discharge to home without services, and (2) discharge to home with HHC. While not an identical process across all institutions, many TAVR centers utilize standardized discharge checklists or care pathways incorporating preoperative factors such as STS risk score, frailty index, and living situation to determine the need for HHC.

Patients who were discharged to skilled nursing or short-term care facilities were not included in the analysis due to the potential of adding additional confounding variables, such as higher comorbidity burden and higher levels of care. We also excluded patients under 18 years old, cases occurring in the last month of the year (after December 1), and cases with operative mortality. Primary outcomes of interest were in-hospital mortality, postprocedural complications, and readmissions.

Primary stratification was between home health care (HHC) TAVR patients and TAVR

patients who underwent routine postoperative discharge. Continuous variables were

presented as mean

Patients were then separately propensity-score matched (PSM) to assess 30-day

outcomes after TAVR with HHC vs routine discharge paradigms. Logistic regression

was used to calculate propensity scores based on baseline demographic, clinical,

and operative variables. The matched cohort was generated via 1:1 nearest

neighbor matching without replacement, using a caliper of 0.2 of the standard

deviation of the alogit propensity score. Matched variables included age, female

sex, primary payer (Medicare) status, resident status, patient location, hospital

length of stay, elective nature of the procedure, and metropolitan teaching

hospital status. After matching, standardized mean differences (SMDs) were

calculated to assess covariate balance, with less than

Multivariate logistic regression was performed to identify factors associated

with 30-day readmissions after TAVR. Factors included in the analysis were HHC

status, female sex, state resident status, micropolitan city status, hospital

length of stay, non-elective procedure status, diabetes mellitus, coronary artery

disease, congestive heart failure, aortic aneurysm, chronic lung disease, chronic

kidney disease, hospital bed size, immediate postprocedural myocardial

infarction, heart failure, respiratory failure, acute kidney injury, urinary

tract infection, paraplegia (lower body paralysis), bowel ischemia (malperfusion

to small or large intestine), ileus (temporary loss of bowel motility),

hemorrhage, and arrhythmia. These variables were selected on the basis of

clinical judgment and prior evidence. All statistical analyses were performed

with SAS/STAT Version 15.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). All tests were

2-sided with an

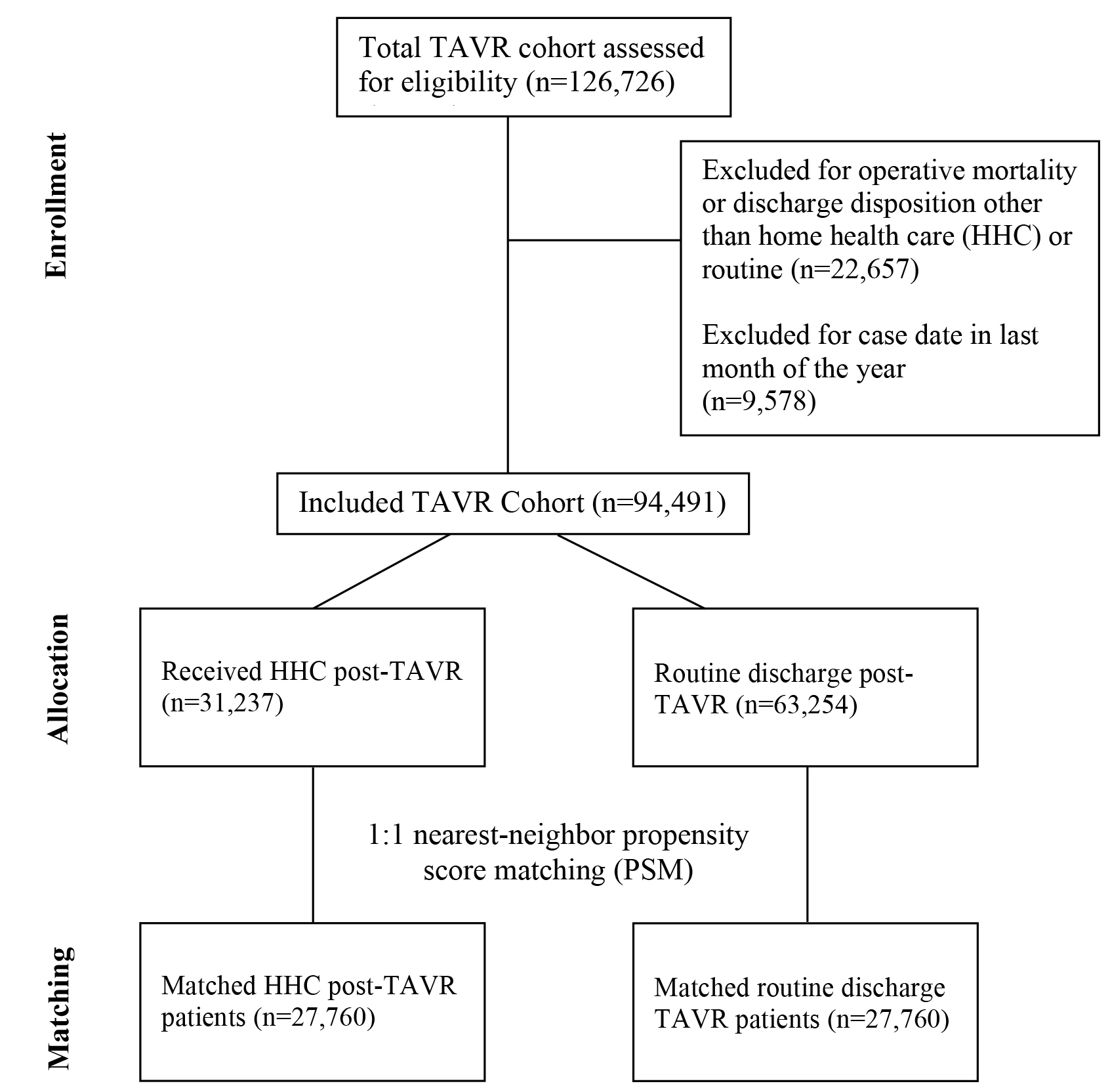

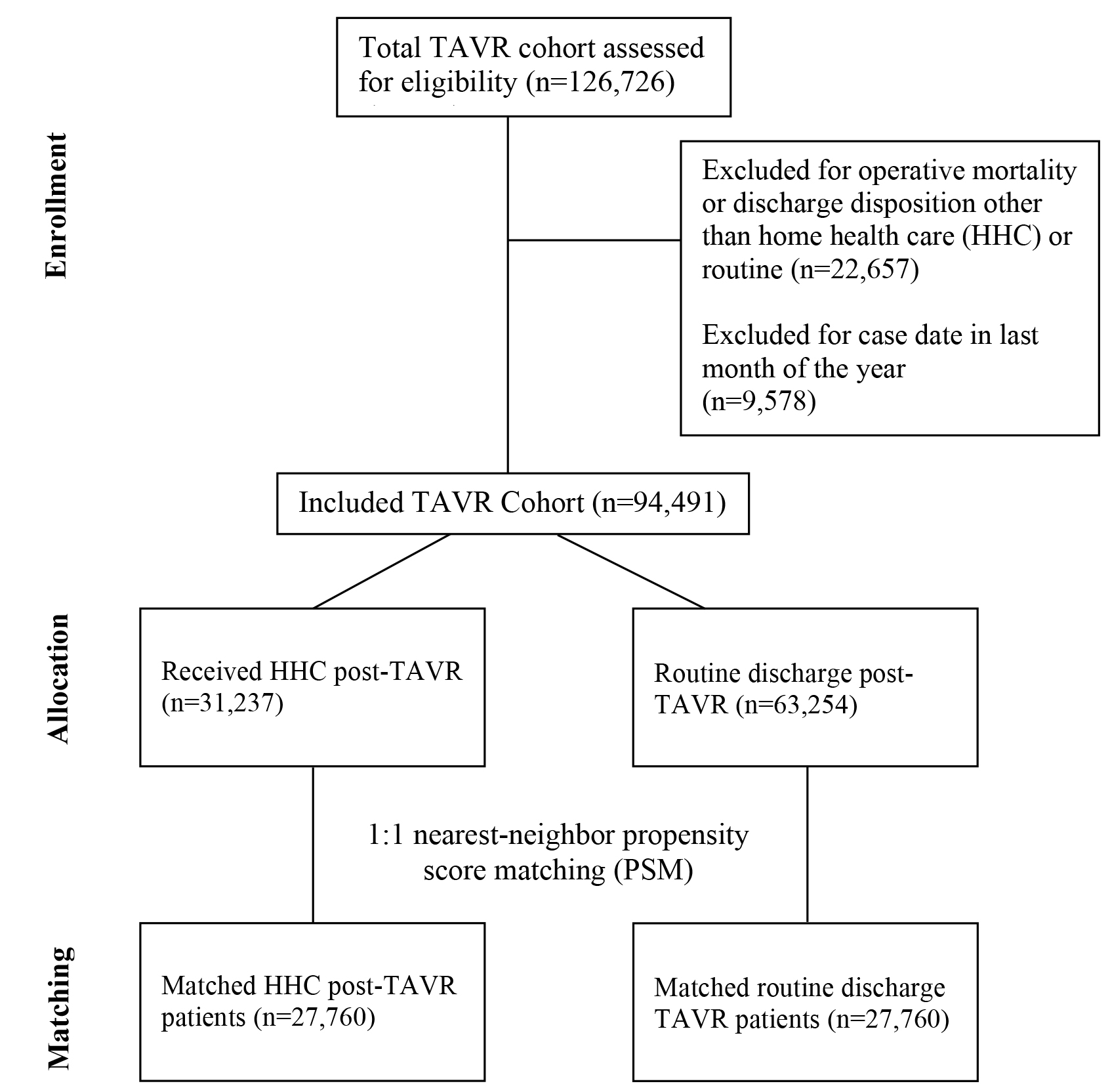

A total of 94,491 patients who underwent TAVR between 2010–2018 as listed in

the NRD were included in this study. Of the included patients, 31,237 (33.1%)

received HHC while 63,254 (66.9%) underwent routine discharge following TAVR

(Fig. 1). Baseline characteristics were reported and compared between groups in

Table 1. HHC patients were more often older, female, and Medicare recipients as

compared to those in the routine discharge group. Notably, a higher number of

patients in the HHC cohort underwent TAVRs at teaching hospitals (91.4% vs.

87.5%, p

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

CONSORT flowchart showing inclusion of HHC and TAVR participants throughout the study. TAVR, transcatheter aortic valve replacement; HHC, home health care.

| Variable | Routine (n = 63,254) | HHC (n = 31,237) | p-value | |

| Age (years) | 81.0 (74.0–86.0) | 83.0 (77.0–87.0) | ||

| Sex: Female | 26,450 (41.8%) | 15,215 (48.7%) | ||

| Primary payer | ||||

| Medicare | 56,255 (88.9%) | 29,048 (93.0%) | ||

| Medicaid | 777 (1.2%) | 307 (1.0%) | ||

| Private insurance | 4676 (7.4%) | 1445 (4.6%) | ||

| Self-pay | 310 (0.49%) | 118 (0.4%) | ||

| No charge | 12 (0.0%) | 8 (0.0%) | ||

| Other | 1148 (1.8%) | 280 (0.9%) | ||

| Resident status | 56,795 (89.8%) | 28,399 (90.9%) | ||

| Median household income | ||||

| 0–25th percentile | 12,526 (19.8%) | 5381 (17.2%) | ||

| 26th–50th percentile | 16,496 (26.1%) | 7069 (22.6%) | ||

| 51st–75th percentile | 17,274 (27.3%) | 8200 (26.3%) | ||

| 76th–100th percentile | 16,035 (25.4%) | 10,224 (32.7%) | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 24,750 (39.1%) | 12,588 (40.3%) | ||

| Dyslipidemia | 45,110 (71.3%) | 21,926 (70.2%) | ||

| Coagulation disorder | 7333 (11.6%) | 5872 (18.8%) | ||

| Hypertension | 55,523 (87.8%) | 27,410 (87.8%) | 0.90 | |

| Coronary artery disease | 45,019 (71.2%) | 22,575 (72.3%) | ||

| Congestive heart failure | 44,969 (71.1%) | 22,674 (72.6%) | ||

| Cerebrovascular disease | 6198 (9.8%) | 3611 (11.6%) | ||

| Peripheral vascular disease | 11,422 (18.1%) | 7141 (22.9%) | ||

| Aortic aneurysm | 3444 (5.4%) | 2164 (6.9%) | ||

| Chronic lung disease | 14,694 (23.2%) | 8342 (26.7%) | ||

| Chronic kidney disease | 20,568 (32.5%) | 11,736 (37.6%) | ||

| Elective procedure | 61,902 (97.9%) | 30,682 (98.2%) | ||

| Variable | Routine (n = 63,254) | HHC (n = 31,237) | p-value | |

| Hospital bed capacity | ||||

| Small | 3029 (4.8%) | 770 (2.5%) | ||

| Medium | 11,565 (18.3%) | 6948 (22.2%) | ||

| Large | 48,660 (76.9%) | 23,519 (75.3%) | ||

| Hospital Control | ||||

| Government, nonfederal | 5420 (8.6%) | 2504 (8.0%) | ||

| Private, not-profit | 53,033 (83.8%) | 26,452 (84.7%) | ||

| Private, invest-own | 4801 (7.6%) | 2281 (7.3%) | ||

| City Population | ||||

| Large metropolitan ( |

39,111 (61.8%) | 23,450 (75.1%) | ||

| Small metropolitan ( |

23,656 (37.4%) | 7669 (24.6%) | ||

| Micropolitan areas | 476 (0.8%) | 113 (0.4%) | ||

| Non metropolitan or micropolitan (non-urban residual) | 11 (0.0%) | 5 (0.0%) | ||

| Teaching status | ||||

| Metropolitan non-teaching | 7422 (11.7%) | 2578 (8.3%) | ||

| Metropolitan teaching | 55,345 (87.5%) | 28,541 (91.4%) | ||

| Non-metropolitan hospital | 487 (0.8%) | 118 (0.4%) | ||

| Hospital length of stay (days) | 2.0 (1.0–3.0) | 4.0 (3.0–8.0) | ||

Propensity matching of the routine discharge and HHC cohorts was performed to

balance patient covariates between groups. Table 3 presents baseline data for the

matched cohort (n = 55,520) comparing HHC (n = 27,760) with routine (n = 27,760)

discharge groups. After matching, groups were acceptably balanced across all

baseline variables (

| Variable | Routine (n = 27,760) | HHC (n = 27,760) | SMD |

| Age (years) | 83.0 (77.0–87.0) | 83.0 (77.0–87.0) | 0.02 |

| Sex: Female | 13,597 (49.0%) | 13,353 (48.1%) | 0.02 |

| Primary payer (Medicare) | 25,792 (92.9%) | 25,746 (92.7%) | 0.02 |

| Resident status | 25,081 (90.4%) | 25,157 (90.6%) | 0.01 |

| Patient location (central counties of metropolitan areas) | 7389 (26.6%) | 7249 (26.1%) | 0.07 |

| Length of stay (days) | 3.0 (2.0–5.0) | 4.0 (2.0–7.0) | 0.15 |

| Elective procedure | 22,260 (80.2%) | 21,816 (78.6%) | 0.04 |

| Metropolitan teaching hospital | 25,360 (91.4%) | 25,264 (91.0%) | 0.01 |

Postoperative outcomes of propensity-matched HHC and routine discharge patients

are reported in Table 4. Following TAVR, frequency of myocardial infarction (MI),

arrhythmia, acute kidney injury, urinary tract infection, stroke, ileus, sepsis,

hemorrhage, 30-day readmissions, and early mortality (within 30 days of index

procedure) were significantly higher in those receiving HHC compared to routine

discharge patients (p

| Variable | Routine (n = 27,760) | HHC (n = 27,760) | p-value |

| Myocardial infarction | 790 (2.9%) | 892 (3.2%) | 0.01 |

| Heart failure | 8885 (32.0%) | 8373 (30.2%) | |

| Arrhythmia | 9444 (34.0%) | 10,055 (36.2%) | |

| Pneumonia | 474 (1.7%) | 527 (1.9%) | 0.09 |

| Acute kidney injury | 2676 (9.6%) | 3406 (12.3%) | |

| Urinary tract infection | 1834 (6.6%) | 2347 (8.5%) | |

| Paraplegia | 13 (0.1%) | 17 (0.1%) | 0.47 |

| Bowel ischemia | 44 (0.2%) | 55 (0.2%) | 0.27 |

| Stroke | 150 (0.5%) | 210 (0.8%) | |

| Ileus | 80 (0.3%) | 127 (0.5%) | |

| Sepsis | 93 (0.3%) | 137 (0.5%) | |

| Hemorrhage | 4918 (17.7%) | 5792 (20.9%) | |

| 30-day readmission | 4376 (15.8%) | 5513 (19.9%) | |

| 30-day mortality | 72 (0.3%) | 108 (0.4%) |

On multivariate logistic regression, HHC discharge paradigm was significantly

associated with an increased risk of 30-day hospital readmission after TAVR (HR:

1.34; 95% CI: 1.30–1.38; p

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | p-value | ||

| Home health care (ref: routine discharge) | 1.34 | 1.30 | 1.38 | ||

| Sex: Female (ref: male) | 1.03 | 1.01 | 1.06 | 0.02 | |

| State Resident | 1.87 | 1.77 | 1.96 | ||

| Hospital in micropolitan area (ref: metropolitan area) | 4.28 | 1.14 | 16.01 | 0.03 | |

| Hospital LOS (days) | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | ||

| Non-elective procedure (ref: elective) | 1.23 | 1.19 | 1.28 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus (ref: asymptomatic) | 1.05 | 1.02 | 1.08 | ||

| Coronary artery disease (ref: asymptomatic) | 1.10 | 1.07 | 1.13 | ||

| Congestive heart failure (ref: asymptomatic) | 1.21 | 1.17 | 1.25 | ||

| Aortic aneurysm | 1.09 | 1.03 | 1.15 | ||

| Chronic lung disease (ref: asymptomatic) | 1.19 | 1.15 | 1.22 | ||

| Chronic kidney disease (ref: asymptomatic) | 1.37 | 1.33 | 1.40 | ||

| Hospital bed size (Small) | 1.05 | 0.99 | 1.12 | 0.13 | |

| Median household income (ref: 0–25th percentile) | |||||

| 26th–50th percentile | 0.99 | 0.96 | 1.03 | 0.73 | |

| 51st–75th percentile | 0.94 | 0.91 | 0.98 | ||

| 76th–100th percentile | 0.90 | 0.87 | 0.94 | ||

| TAVR Complications | |||||

| Myocardial infarction (ref: unaffected) | 1.24 | 1.15 | 1.33 | ||

| Heart failure (ref: unaffected) | 1.14 | 1.10 | 1.17 | ||

| Respiratory failure (ref: unaffected) | 1.12 | 1.02 | 1.23 | 0.02 | |

| Acute kidney injury (ref: unaffected) | 1.27 | 1.22 | 1.33 | ||

| Urinary tract infection (ref: unaffected) | 1.11 | 1.05 | 1.16 | ||

| Paraplegia (ref: unaffected) | 2.10 | 1.30 | 3.39 | ||

| Bowel ischemia (ref: unaffected) | 1.42 | 1.07 | 1.88 | 0.02 | |

| Ileus (ref: unaffected) | 1.35 | 1.11 | 1.64 | ||

| Hemorrhage (ref: unaffected) | 1.07 | 1.03 | 1.11 | ||

| Arrhythmia (ref: unaffected) | 1.03 | 1.00 | 1.06 | 0.07 | |

LOS, length of stay.

In this study, we present a propensity-matched analysis of the postoperative clinical outcomes in the Nationwide Readmissions Database TAVR patients who underwent discharge via HHC vs routine to home. After 1:1 nearest-neighbor PSM, HHC TAVR patients experienced significantly higher rates of early mortality compared to routine discharge patients (0.47% vs. 0.20%, respectively). Moreover, rates of 30-day readmission, postoperative MI, arrhythmia, acute kidney injury, stroke/TIA, and sepsis were also significantly higher in HHC patients, while incidence of heart failure was higher in routine discharge patients. On multivariate logistic regression, HHC conferred a significantly increased risk of 30-day readmission following TAVR (HR: 1.34; 95% CI: 1.30–1.38). Though these findings should be bolstered by additional studies with longer clinical follow-up, the data here suggest that in TAVR patients, HHC is significantly associated with increased short-term morbidities and early mortality when compared to routine discharge patients.

Albeit limited in comparison to surgical aortic valve replacement, early complications following TAVR have been well-documented by recent randomized control trials and observational studies. Several major complications have been consistently identified in the periprocedural period following TAVR, namely moderate/severe paravalvular leakage (PVL), stroke, major vascular and bleeding complications, conduction abnormalities necessitating permanent pacemaker placement, and acute kidney injury [13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19]. Further expounding upon this evidence, studies have shown early moderate-to-severe PVL and major bleeding to be specifically associated with increased 1-year postprocedural mortality and decreased quality of life as measured by Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire score [20]. Strategies have therefore recently been devised to limit such acute complications following TAVR, with institutions demonstrating the efficacy of various prophylactic and measurement devices such as stroke management protocols and aortic regurgitation indices for valvular dysfunction quantification [14, 21]. Nonetheless, as TAVR valves continue to evolve in morphology and function, similar to what has been seen with recent developments in cerebral embolic protection and anti-leak perivalvular occlusion, further reductions in initial postprocedural morbidities are expected [22, 23].

Comprised of home health assistants, nursing, and rehabilitation services, HHC is a system of care, similar to skilled nursing facilities and inpatient rehabilitation centers, that provides patients with multidisciplinary surveillance following a visit to an acute care institution [24]. HHC serves as an attractive paradigm to reduce the rate of early morbidities in the post-hospital setting as various analyses have shown HHC to be associated with advantageous outcomes such as lower 1-year mortality and readmission rates when compared to incomplete HHC [25, 26]. However, patients being managed for cardiac disease pathologies do not seem to experience similar benefits of HHC. HHC has been attributed to increased 30-day readmission rates following both HF admissions and transcatheter mitral valve repair, likely due to these patients having worse overall health status preceding TAVR [9, 10, 11]. This trend is consistent amongst TAVR patients as well, with a recent study using the NRD by Nazir et al. [12] showing that even after adjusting for covariates amongst TAVR patients, HHC utilization was correlated with longer median hospital length of stay, higher rates of 30-day all-cause readmissions, and 30-day heart failure readmissions compared to those who did not receive HHC. Outside of these few analyses, there is a general paucity of data comparing HHC vs routine discharge patients in a post-TAVR setting.

Here, we show that in propensity-matched TAVR patients, HHC is associated with a significantly higher risk of early mortality and 30-day hospital readmission compared to the routine discharge paradigm. Though many factors may explain the poorer outcomes associated with HHC in the studied TAVR cohort, it is plausible that the increased presence of trained healthcare professionals in the post-hospital setting may result in early detection of postprocedural complications, thereby resulting in increased hospital readmissions. Additionally, HHC programs may vary in structure on an institutional basis, such that inconsistencies in follow-up, care practices, and protocolization may affect post-procedural outcomes. Lastly, HHC utilization may also be associated with lower patient health literacy and socioeconomic status, both of which were unable to be accounted for in PSM, and are individual predictors for worsened outcomes after TAVR [27].

It is important to note that while differences in a variety of outcomes between HHC and routine discharge groups were found to be statistically significant, absolute effect sizes of these respective outcomes varied. For example, in the propensity-matched discharge groups, early mortality differed by 0.1% and early readmissions by 4.1%, with both outcomes found to be significantly higher in TAVR patients discharged to HHC. Nonetheless, we contend that even a 4.1% increase in readmissions after HHC is a clinically relevant outcome, especially given that typical 30-day all-cause readmission after TAVR occurs in roughly 15–17% of patients, suggesting nearly a 25% relative increase in readmissions [28]. Moreover, readmissions after TAVR have been shown to confer increased mortality risk, effectively augmenting the risk profile of the index procedure [27]. While the results of this retrospective analysis do not call for the direct rejection of HHC-guided postprocedural patient management, further comparative studies are required to justify the recommendation of such discharge practices in TAVR patients.

This study has several important limitations. There are inherent limitations in using observational data from large databases. Despite the nearest-neighbor propensity matching used here, this study displays a considerable degree of heterogeneity. Not only is the patient population diverse, but clinical decision-making and techniques can vary significantly between participating institutions. Patients referred for HHC after TAVR likely had a higher comorbidity burden than regularly discharged patients, a difference that could not be adequately adjusted for with PSM. Due to this inherent selection bias, the associations observed in this analysis may be derived from patient comorbidity burden rather than the properties of each respective care modality. Specifically, patient frailty metrics could not be included in our propensity score model due to the lack of these data in the NRD. Future studies of large clinical datasets integrating functional status may prove invaluable in better matching patients receiving HHC compared to regular discharge, further elucidating differences in outcomes between practices. Additionally, given that TAVR involves multidisciplinary efforts, the lack of granularity in such broad data repositories often fails to capture nuances in detailed variables that could explain differences in outcomes between HHC and routine discharge patients.

Additionally, large database studies with large sample sizes can detect small differences in data. Although statistically significant, these differences may not be clinically relevant. Therefore, to address such limitations, the results of large database studies should be further explored in tandem with single-institution analyses. Lastly, the NRD includes patients from 30 states in the United States. While comprehensive, the generalizability of this study’s findings may be limited as HHC practices may vary on a state-by-state or international basis.

After TAVR, the use of HHC services was correlated with higher in-hospital morbidities and an increased risk of 30-day readmission. Enhancing discharge procedures prior to HHC and revising HHC eligibility criteria could improve overall outcomes. For instance, frailty assessments, such as the 6-minute walk test, can be used as metrics to potentially predict non-home and HHC outcomes. Moreover, standardized implementation of such HHC eligibility criteria in the preoperative setting can allow for faster and more targeted use of adjunct rehabilitative services that benefit HHC TAVR patients with comorbidities likely driving higher hospital readmissions.

Data may be made available upon reasonable request to corresponding author.

EA, DA, IS contributed to study conception and design. EA, DA, YW contributed to data collection and analysis. SY, JAB, DSG, DK, CT, DW and AM contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data for the work. EA, DA, SY, JAB, YW, DSG, DK, CT, DW, AM, IS contributed to manuscript drafting and revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The study was carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Pittsburgh approved on 4/17/2019 (STUDY18120143). Informed consent not applicable as data was obtained through the NRD.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

Dr. Sultan receives institutional research support from Abbott, Atricure, Artivion, WL Gore, Edwards, Medtronic, and Terumo Aortic. None of these are related to this manuscript. The remaining authors have no competing interests to declare.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/HSF48321.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.