1 Department of Cardiology, Yangpu Hospital, Tongji University School of Medicine, 200090 Shanghai, China

2 Department of Cardiology, Shanghai Tenth People’s Hospital, Tongji University School of Medicine, 200072 Shanghai, China

Abstract

Free fatty acids (FFA) are promising biomarkers for the diagnosis and assessment of several diseases. They have been associated with cardiovascular diseases, such as insulin resistance, arteriosclerosis, myocardial dysfunction, cardiac arrhythmias, and sudden cardiac death; thus, it is important to study the relationship between FFA and atrial fibrillation (AF), especially whether FFAs can predict AF recurrence after catheter ablation.

Patients with symptomatic paroxysmal or persistent AF undergoing radiofrequency catheter ablation for the first time were included in the study. Plasma FFA levels were measured upon admission and 3 months after ablation.

A total of 88 patients with AF (55 males, 33 females; mean age, 62.5 ± 8.7 years) were included for analysis. FFA levels upon admission in patients with paroxysmal and persistent AF were 0.38 ± 0.16 and 0.37 ± 0.15 mmol/L, respectively. During the 3-month follow-up after radiofrequency ablation, FFA concentration in patients with paroxysmal and persistent AF were 0.38 ± 0.18 and 0.36 ± 0.18 mmol/L, respectively. FFA concentration in patients with and without AF recurrence were 0.69 ± 0.07 and 0.33 ± 0.14 mmol/L, respectively. Kaplan–Meier analysis showed that AF recurrence was significantly higher in patients with FFA ≥0.53 mmol/L than in patients with FFA <0.53 mmol/L (p < 0.001). FFA concentration at 3 months post-ablation was an independent predictor of AF recurrence in patients who underwent catheter ablation (hazard ratio = 10.45, 95% CI [8.61–25.33], p = 0.03).

Elevated postoperative FFA levels were closely related to AF recurrence at the 1-year follow-up, implying that postoperative FFA levels can be used as a predictive biomarker for AF recurrence. FFAs may be used as a new therapeutic target for the prevention and treatment of AF.

Keywords

- atrial fibrillation

- catheter ablation

- recurrence

- free fatty acids

- biomarker

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a common arrhythmia with an incidence of 0.5%,

which increases to 6% in patients

Radiofrequency ablation has recently become an important non-pharmacological treatment for AF [3]. However, recurrence rates after ablation remain high, reaching 20–30% [6]. This presents significant challenges for clinical management of AF, and the factors that affect recurrence are not yet understood. In recent years, the discussion of AF recurrence factors after ablation has become a major focus of research [7], highlighting a potential relationship between certain blood biochemical markers and AF occurrence. However, whether these markers are associated with post-ablation recurrence remains controversial.

Free fatty acids (FFA), also known as non-esterified fatty acids, are important energy substrates in the body [8]. FFA is a product of fat lipolysis, as a constituent component of triglyceride, which binds to albumin and circulates in the plasma [9]. FFA have been associated with cardiovascular diseases, such as insulin resistance, arteriosclerosis, myocardial dysfunction, cardiac arrhythmias, and sudden cardiac death [10, 11, 12]. Some metabolic syndromes increase the incidence of AF [13, 14], and FFA are closely associated with ischemic stroke [15]; thus, given these connections, it is important to study the relationship between FFA and AF, especially whether FFAs can be used to predict the recurrence of AF post-ablation.

This study measured plasma FFA levels in patients with AF undergoing catheter ablation to explore the role and clinical significance of FFA in predicting AF recurrence post-ablation.

This retrospective single-center study evaluated the predictive value of FFA in

patients with AF who underwent ablation. We consecutively recruited all patients

with AF who were hospitalized at the cardiac center of Shanghai Tenth People’s

Hospital from November 2018 to October 2019. The inclusion criteria were the

diagnosis of AF with documentation using electrocardiography (ECG) or 24-h Holter

monitoring following the American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart

Association (AHA)/European Society of Cardiology (ESC) 2016 guidelines. The

exclusion criteria were as follows: age

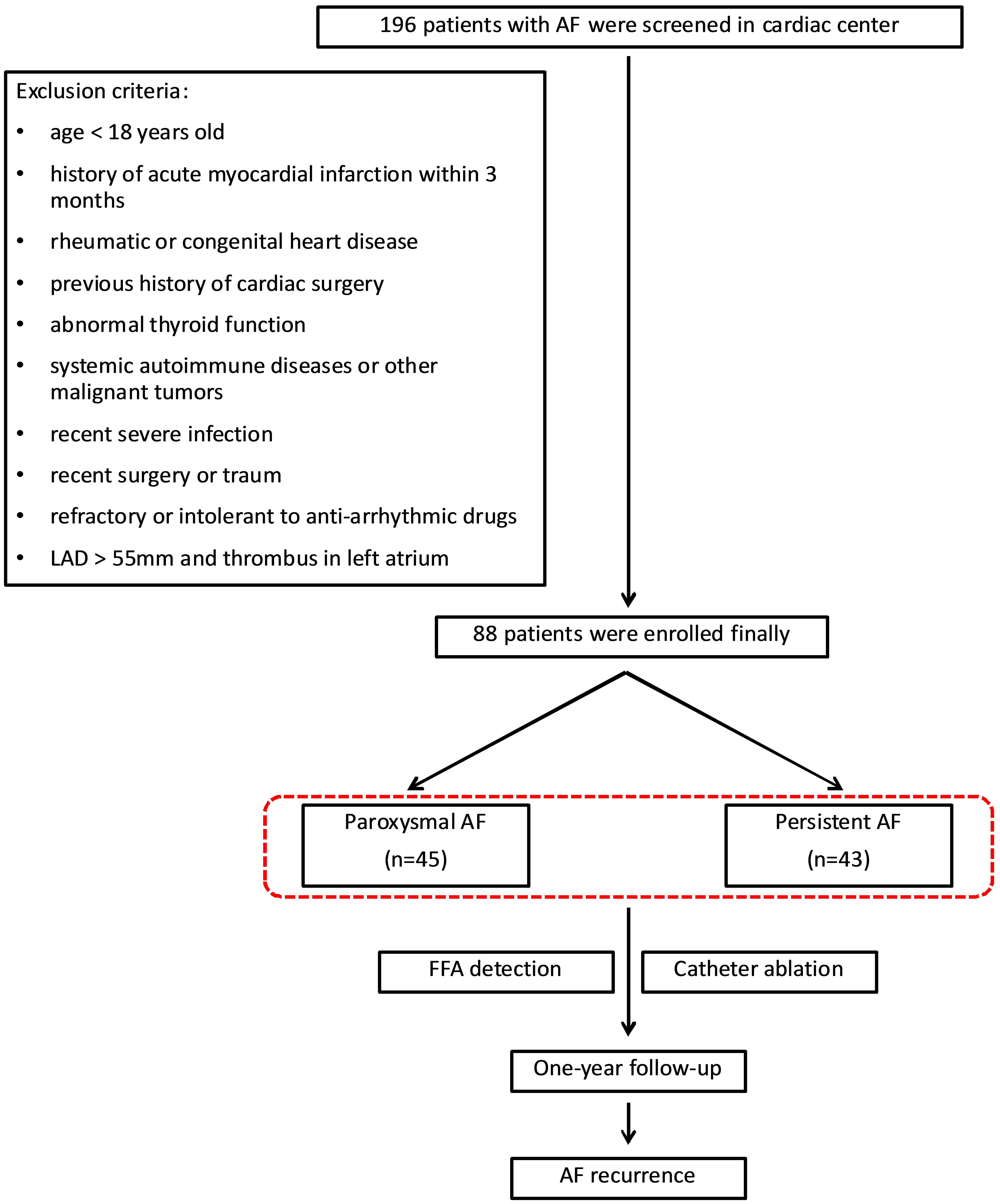

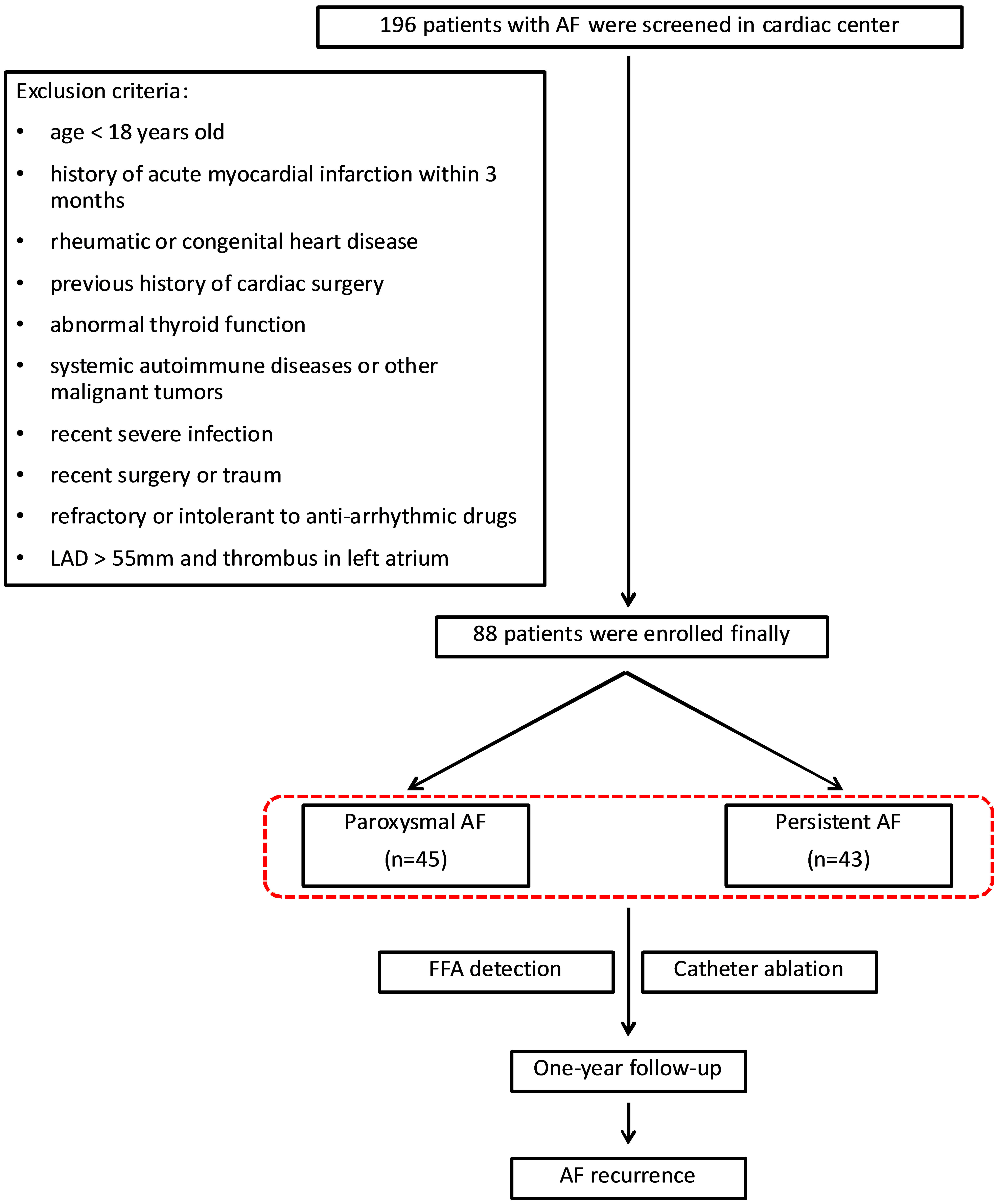

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of patient enrollment and follow-up. A total of 88 patients were included in the study. AF, atrial fibrillation; LAD, left atrial diameter; FFA, free fatty acids.

All patients received anticoagulation therapy for at least 6 weeks before radiofrequency ablation. All patients underwent routine blood tests, thyroid hormone level tests, ECG, Holter monitoring, chest radiography, and transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography before ablation. The left atrium and pulmonary veins were assessed using computed tomography scans.

Anesthesia was induced with fentanyl and midazolam. After femoral vein puncture, a 6F steerable catheter (Inquiry, St. Jude Medical, Inc., St. Paul, MN, USA) and a 5F quadripolar catheter (Medtronic, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA) were placed in the coronary sinus and apex of the right ventricle, respectively. Following transseptal puncture, intravenous unfractionated heparin was administered to maintain an activated clotting time of 250–350 s. Three-dimensional electroanatomical mapping of the left atrium and pulmonary veins was performed using a non-fluoroscopic navigation system (CARTO 3, version 2, Biosense Webster Inc., Irvine, CA, USA), as previously described.

Electrical isolation of the pulmonary veins was confirmed using a circular multipolar electrode-mapping catheter (Lasso Biosense Webster, Irvine, CA, USA). Additional linear ablation, including the left atrial posterior wall line, mitral isthmus line, and left atrial roof line, was performed if AF persisted after pulmonary vein isolation. Some patients underwent complex fractionated atrial electrography and mitral isthmus ablation. Pharmaceutical (ibutilide or aminodarone) or electrical cardioversion was performed if AF persisted after ablation.

Patients were closely monitored during and after the procedure for acute complications, including pericardial tamponade, epicardial coronary injury, phrenic nerve injury, arrhythmia, and mortality.

Antiarrhythmic therapy and anticoagulation were maintained for 3 months

postoperatively in all patients. Follow-up examinations were conducted at 3-, 6-,

and 12-months post-ablation, which included 24-h Holter monitoring, surface ECG,

and plasma FFA measurement. AF recurrence was defined as atrial arrhythmia

lasting

Patient blood samples were obtained upon admission, before radiofrequency ablation. All samples for determining biomarker concentrations were drawn in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid-containing vacuum containers and stored at –80 °C until assayed. Plasma FFA levels were measured by a Quantification Kit (Sigma-Aldrich, Merck KGaA, St Louis, MO, USA; Catalogue number MAK044 SIGMA) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Measurements were made in duplicate and averaged.

Plasma levels of malonyldialdehyde (MDA), superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione (GSH), and total antioxidant capacity were assessed using commercial assay kits (Jian Cheng Biological Engineering Institute, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China).

Data analysis was performed using SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 19.0, Chicago, IL, USA). Differences among the groups were compared using chi-square tests for categorical variables. Two-tailed Student’s t-test were used to compare data between two groups with normal distributed values. Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare data between two groups with non-normal distributed values.

Time dependent Cox proportional-hazards regression model was performed to

identify independent predictors for AF recurrence after ablation. Adjusted model

were done based age, gender, body mass index (BMI), medical history, left atrial

diameter, CHA2DS2-VASc score, estimated glomerular filtration rate

(eGFR), left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), FFA levels and procedure time

to exclude confounding factors. Other variables significantly associated with the

outcome were entered into the model in a stepwise manner. Event-free survival was

analyzed using Kaplan–Meier curves and compared using the log-rank test.

Statistical significance was set at p

A total of 88 patients with AF (55 males, 33 females; mean age, 62.5

| Variable | Paroxysmal AF (n = 45) | Persistent AF (n = 43) | Total (N = 88) | p-value | |

| Age, years | 61.8 |

63.1 |

62.5 |

0.491 | |

| Gender (M/F) | 32/13 | 23/20 | 55/33 | 0.088 | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.8 |

23.9 |

23.9 |

0.970 | |

| Medical history | |||||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 29 (64.4) | 22 (51.2) | 51 (58.0) | 0.207 | |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 16 (35.6) | 17 (39.5) | 33 (37.5) | 0.700 | |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 11 (24.4) | 20 (46.5) | 31 (35.2) | 0.030 | |

| Heart failure, n (%) | 14 (31.1) | 18 (41.9) | 32 (36.4) | 0.295 | |

| Previous stroke/TIA, n (%) | 22 (48.9) | 18 (41.9) | 40 (45.4) | 0.508 | |

| Echocardiogram parameters | |||||

| LAD, mm | 43.5 |

46.3 |

44.9 |

0.001 | |

| LVEF, % | 56.8 |

54.1 |

55.4 |

0.152 | |

| Medications | |||||

| ACEI/ARB, n (%) | 23 (51.1) | 21 (48.8) | 44 (50.0) | 0.831 | |

| Statins, n (%) | 22 (48.9) | 21 (48.8) | 43 (48.9) | 0.996 | |

| 28 (62.2) | 22 (51.2) | 50 (56.8) | 0.295 | ||

| Calcium channel blockers, n (%) | 8 (17.8) | 22 (51.2) | 30 (34.1) | 0.001 | |

| Insulin, n (%) | 5 (11.1) | 4 (9.3) | 9 (10.2) | 1.000 | |

| Diuretics, n (%) | 18 (40.0) | 12 (27.9) | 30 (34.1) | 0.232 | |

| Others | |||||

| Procedure time, min | 175.4 |

178.3 |

176.9 |

0.390 | |

| Fluoroscopy time, min | 46.4 |

51.4 |

48.9 |

0.007 | |

| Radiofrequency time, min | 106.4 |

105.1 |

105.8 |

0.522 | |

| Pulmonary vein isolation, n (%) | 45 (100) | 43 (100) | 88 (100) | 1.000 | |

| Cardioversion, n (%) | 5 (11.1) | 15 (34.9) | 20 (22.7) | 0.008 | |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score | 3.5 |

3.7 |

3.6 |

0.542 | |

| eGFR, mL/min | 83.8 |

87.6 |

85.6 |

0.102 | |

| Free fatty acid, mmol/L | 0.38 |

0.37 |

0.38 |

0.733 | |

AF, atrial fibrillation; M/F, male/female; BMI, body mass index; TIA, transient ischemic attack; LAD, left atrial diameter; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; ACEI/ARB, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

The incidence of coronary heart disease was significantly higher in patients

with persistent AF than in those with paroxysmal AF (46.5% vs. 24.4%,

p = 0.030). The persistent AF group had a significantly larger LAD

(p = 0.001) and longer calcium channel blocker use and fluoroscopy time

(all p

All 88 patients completed the follow-up period without loss. The mean follow-up

duration was 10.5

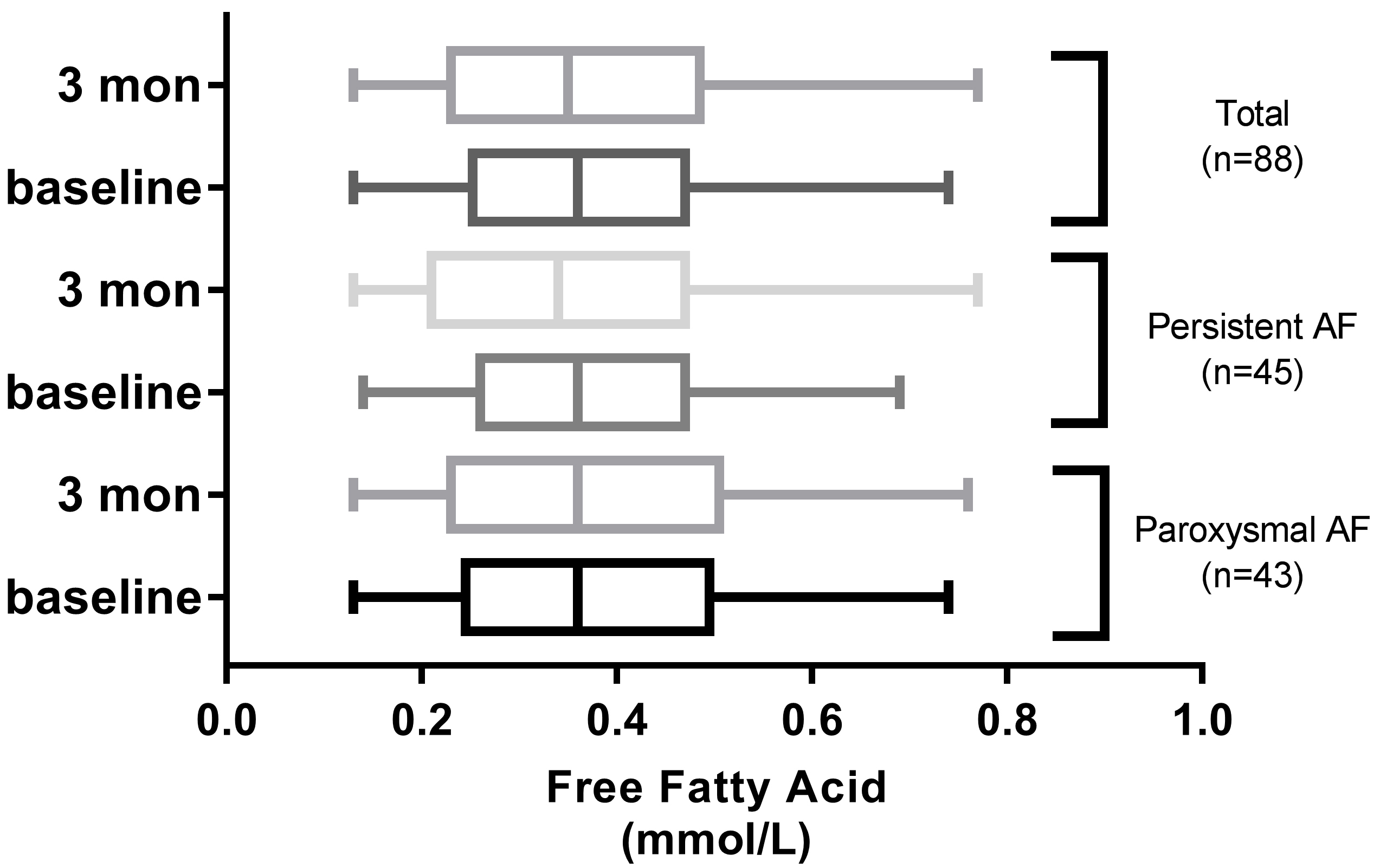

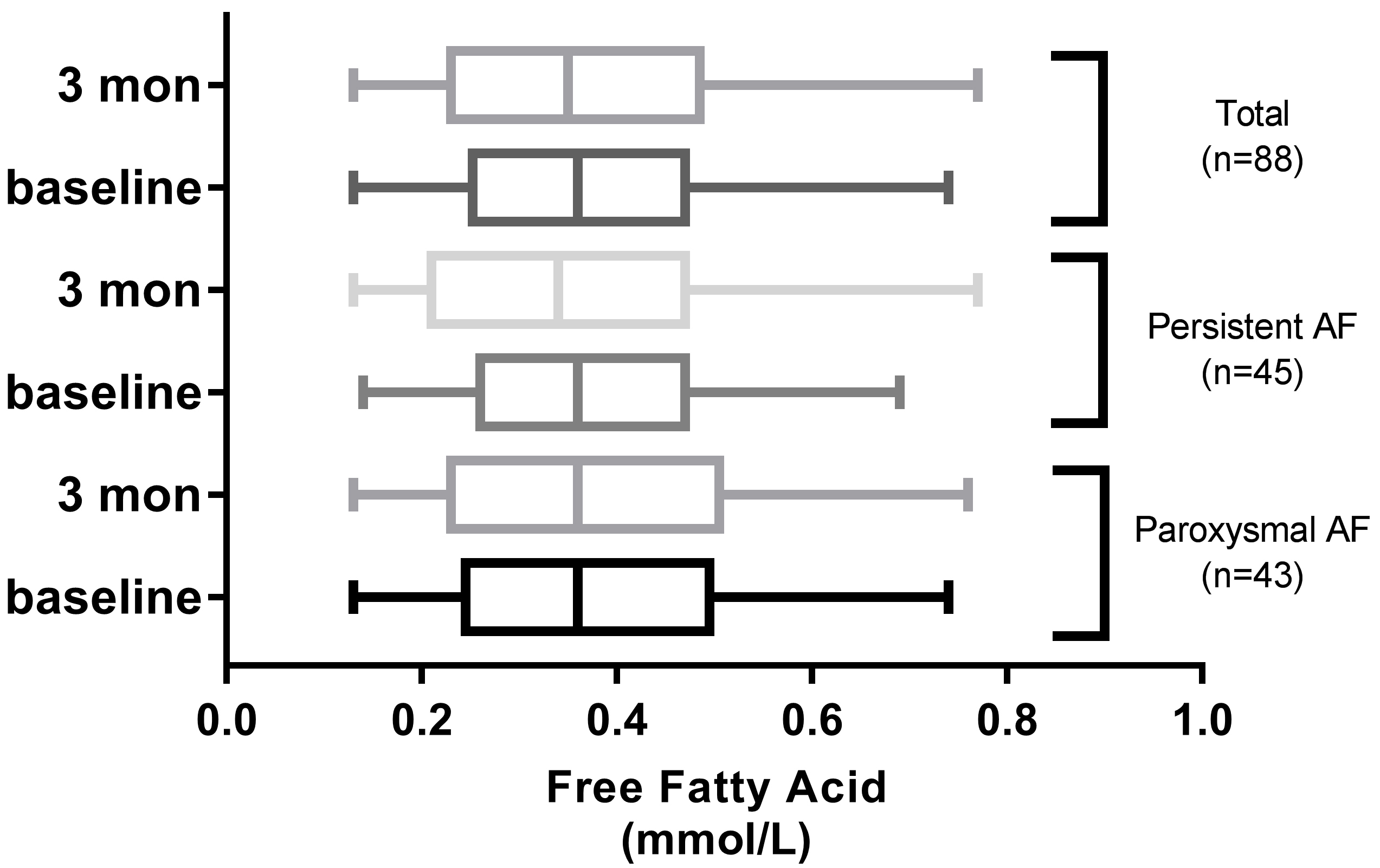

The baseline concentration of FFA in the overall study population was 0.38

A total of 29 patients (paroxysmal AF, n = 18; persistent AF, n = 11) exhibited

higher FFA levels at 3 months post-ablation compared to baseline. The FFA

concentration in patients with and without AF recurrence were 0.69

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of FFA levels between admission and 3 months after discharge in AF groups.

Significant differences were observed in oxidative stress biomarkers between the

groups (p

| Variable | Recurrence group (n = 18) | Non-recurrence group (n = 70) | p-value |

| SOD (U/mL) | 66.4 |

79.2 |

|

| MDA (nmol/mL) | 76.6 |

58.3 |

|

| GSH (mg/L) | 24.1 |

88.6 |

SOD, superoxide dismutase; MDA, malonyldialdehyde; GSH, glutathione.

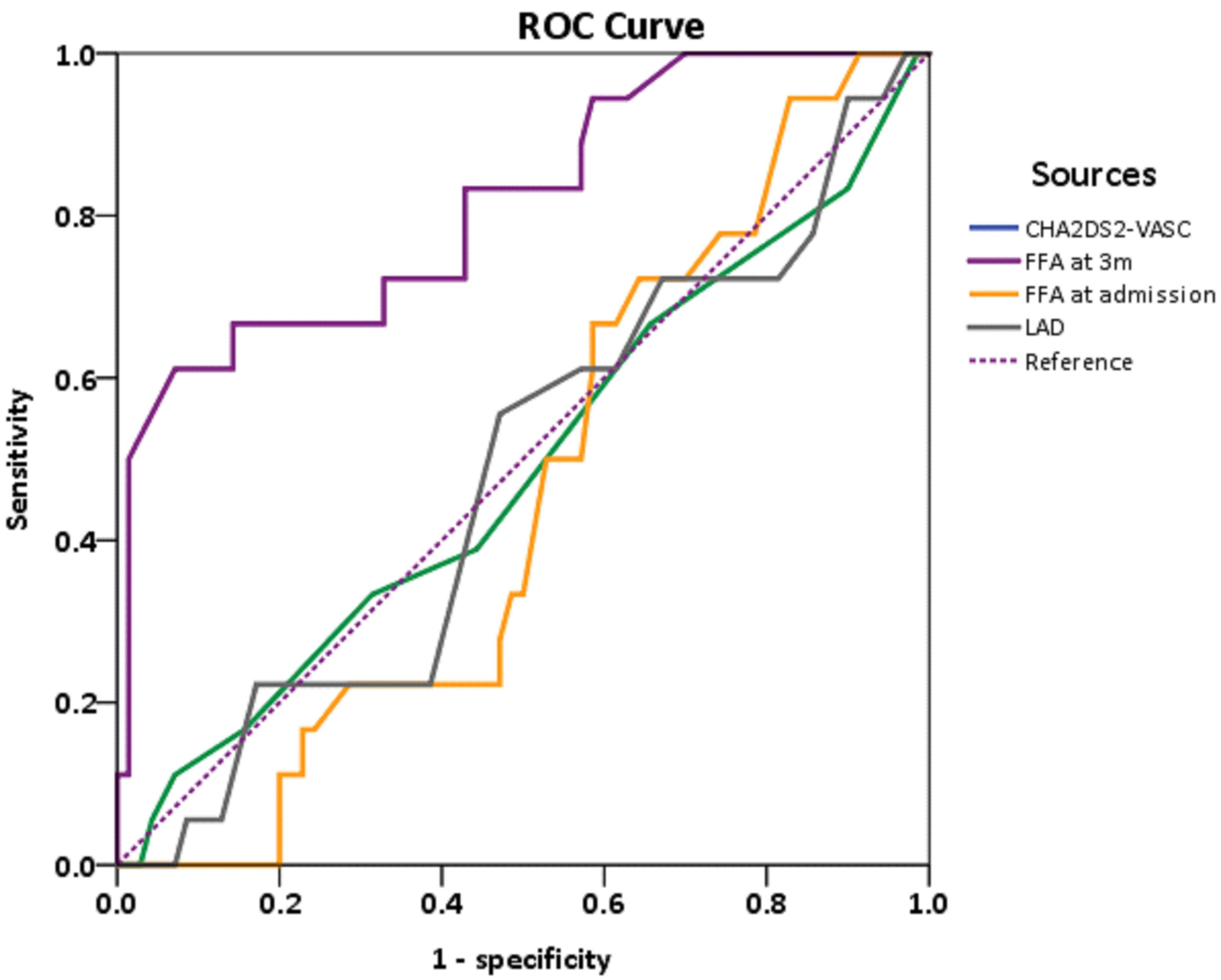

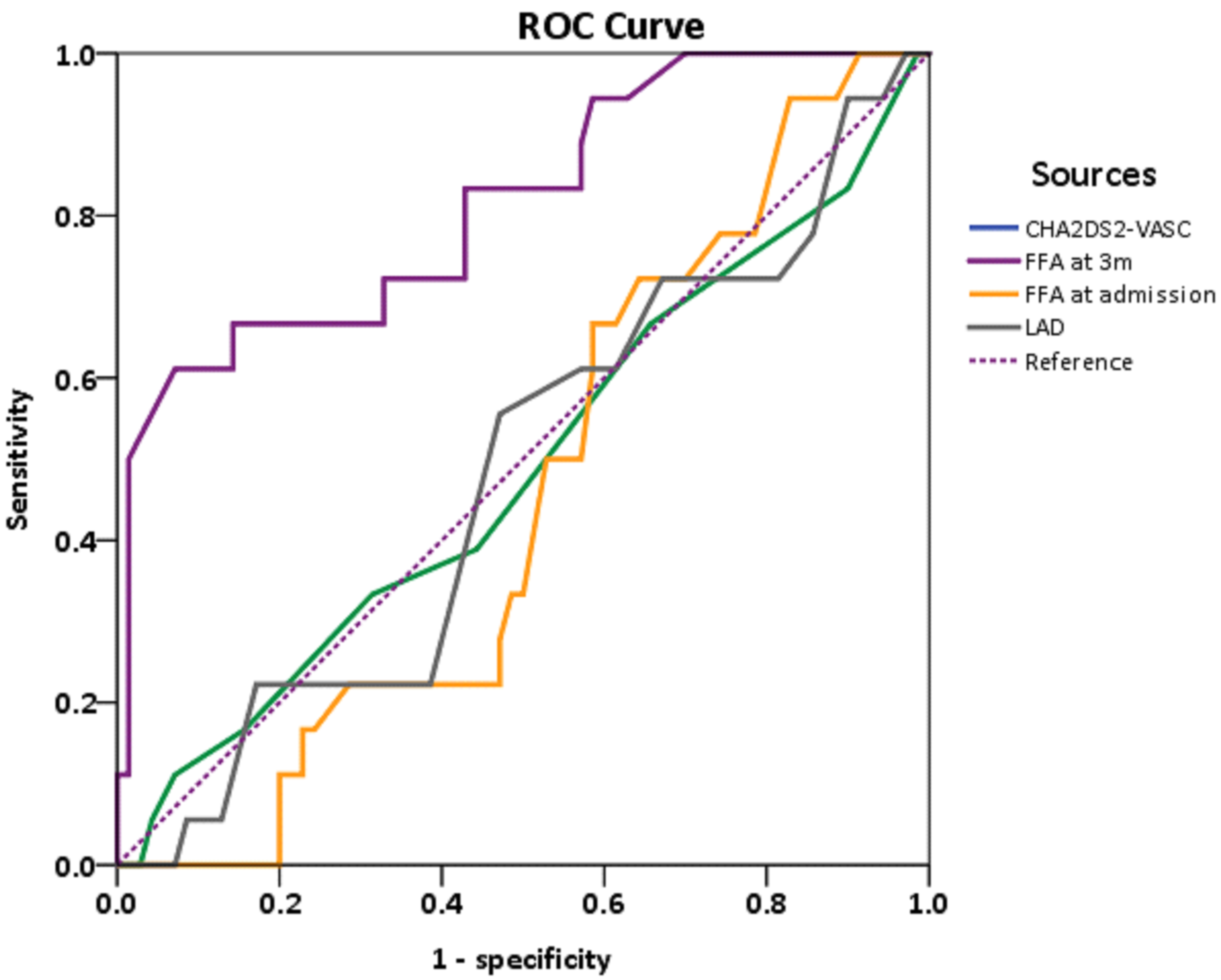

To establish the optimal FFA cutoff value for predicting AF recurrence, ECG and Holter monitoring were used as confirmatory tests. AF recurrence was coded as 1 and non-recurrence was coded as 0. Receiver operating characteristic analysis (y-axis, sensitivity; x-axis, specificity) showed that the area under curve (AUC) for FFA at 3 months post-ablation was 0.82 (95% confidence interval: 0.70–0.93; Fig. 3), while the AUC of CHA2DS2-VASc scoring, FFA at admission, and LAD were 0.49, 0.46, and 0.48, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) of FFA levels upon admission and at 3-month follow-up.

Using 0.53 mmol/L as the threshold, the sensitivity and specificity of FFA were

relatively high at 98% and 94%, respectively. Therefore, in the Kaplan–Meier

survival analysis, patients were classified using 0.53 mmol/L as the cut-off

value:

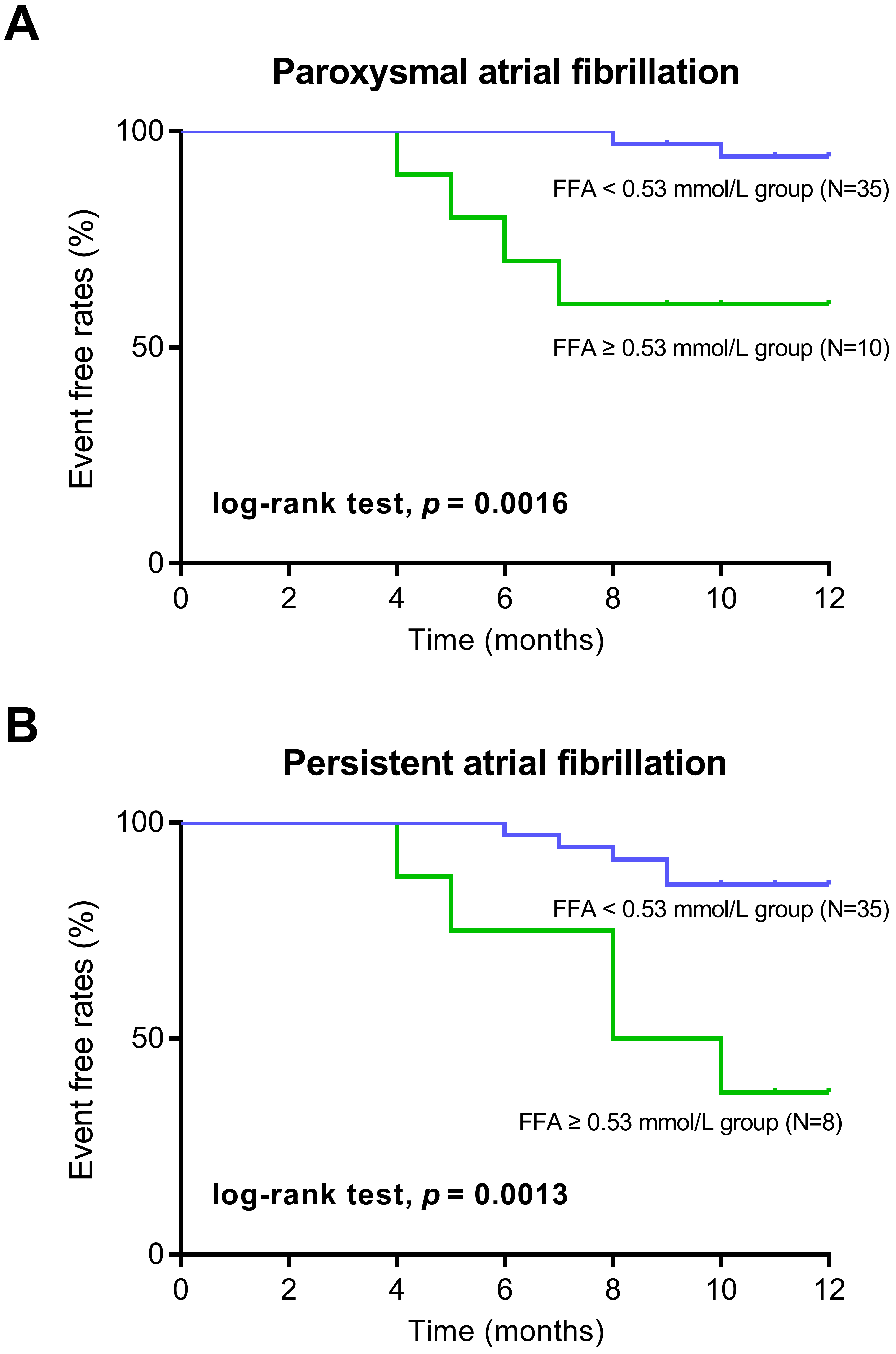

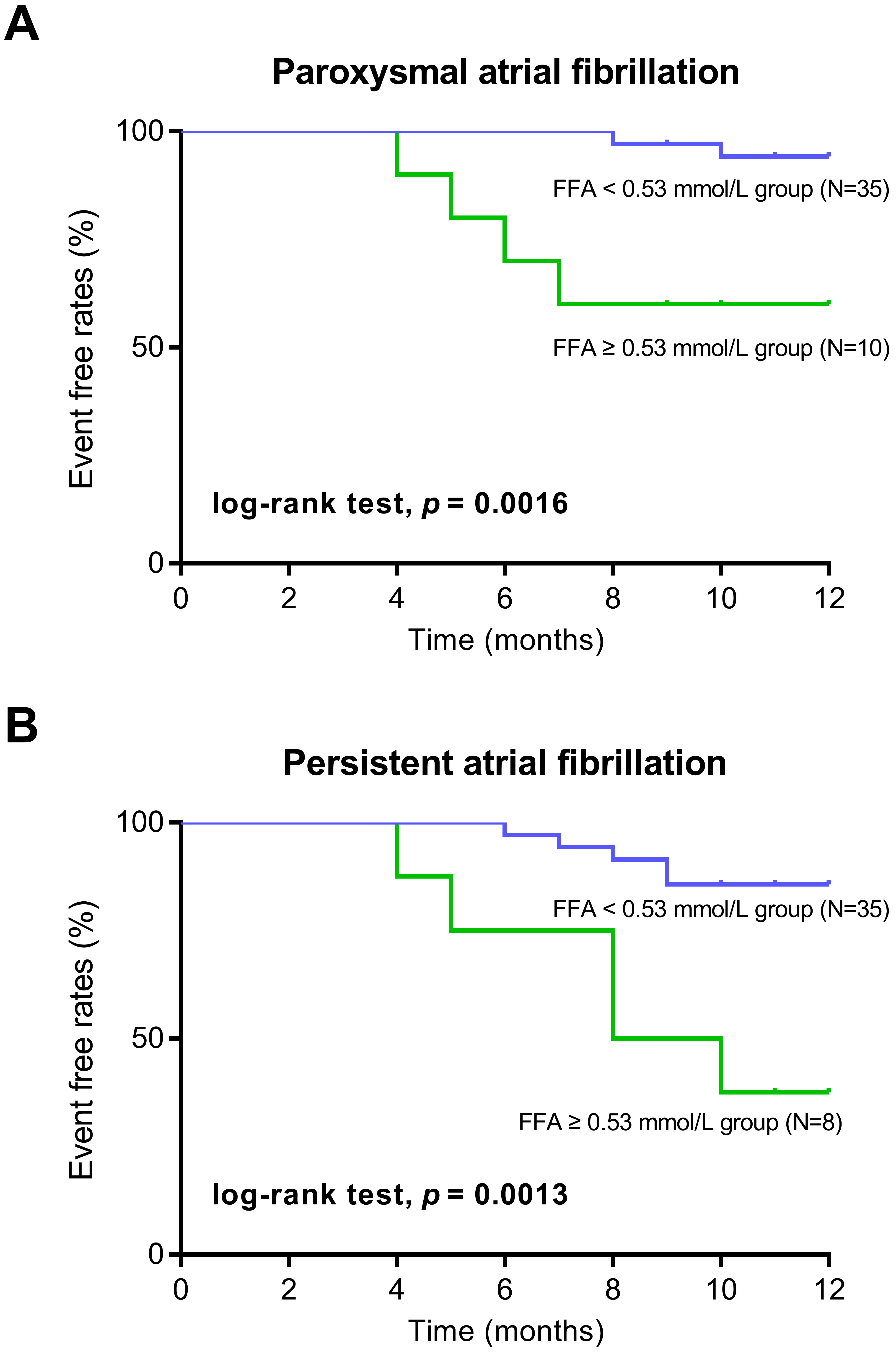

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis showed that in the FFA

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Kaplan–Meier curve analysis of AF recurrence according to FFA levels. (A) Kaplan–Meier curve analysis in the patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. (B) Kaplan–Meier curve analysis in the patients with persistent atrial fibrillation.

Multivariate Cox proportional hazards analysis, including age, gender, BMI, preoperative LVEF and LAD, and preoperative and 3-month postoperative FFA levels, showed that the 3-month post-ablation FFA level was an independent predictor of AF recurrence (hazard ratio = 10.45, 95% CI [8.61–25.33], p = 0.03; Table 3). Reduced LVEF was also a predictor of AF recurrence (Table 3).

| Univariate Cox regression | Multivariate Cox regression | |||||

| Outcome/variables | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | p-value | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | p-value |

| AF recurrence | ||||||

| AF patterns (paroxysmal or persistent AF) | 1.02 | 0.53–1.23 | 0.78 | 1.02 | 0.53–1.23 | 0.78 |

| Age | 1.01 | 0.92–1.11 | 0.81 | 1.02 | 0.92–1.11 | 0.80 |

| Gender | 1.86 | 0.43–9.11 | 0.40 | 1.85 | 0.44–9.12 | 0.41 |

| BMI | 0.93 | 0.71–1.29 | 0.63 | 0.91 | 0.70–1.30 | 0.70 |

| Diabetes | 0.68 | 0.14–2.48 | 0.62 | 0.65 | 0.12–2.47 | 0.61 |

| Hypertension | 1.35 | 0.31–5.55 | 0.68 | 1.32 | 0.33–5.56 | 0.66 |

| Coronary artery disease | 1.03 | 0.14–3.34 | 0.97 | 1.03 | 0.14–3.34 | 0.97 |

| Smoking history | 1.55 | 0.41–7.40 | 0.51 | 1.67 | 0.45–7.52 | 0.78 |

| Heart failure | 0.14 | 0.01–1.81 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.01–1.75 | 0.10 |

| Previous stroke/TIA | 0.29 | 0.03–2.91 | 0.28 | 0.33 | 0.05–2.98 | 0.35 |

| LAD | 0.98 | 0.83–1.11 | 0.81 | 0.91 | 0.78–1.13 | 0.75 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score | 0.77 | 0.31–1.70 | 0.57 | 0.85 | 0.45–1.89 | 0.68 |

| FFA at admission | 0.02 | 0.00–1.44 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.00–1.43 | 0.05 |

| FFA at 3 m | ||||||

| 0.45 | 0.01–1.36 | 0.46 | 0.08 | 0.00–1.33 | 0.87 | |

| 16.74 | 5.73–38.89 | 10.45 | 8.61–25.33 | 0.03 | ||

| eGFR | 1.04 | 0.98–1.07 | 0.18 | 1.14 | 0.95–1.33 | 0.28 |

| Reduced LVEF | 4.99 | 4.37–35.51 | 0.01 | 15.56 | 6.87–18.62 | 0.02 |

| Procedure time | 0.97 | 0.94–1.01 | 0.12 | 0.95 | 0.90–1.12 | 0.18 |

CI, confidence interval; AF, atrial fibrillation; BMI, body mass index; TIA, transient ischemic attack; LAD, left atrial diameter; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; FFA, free fatty acids; 3 m, third month after discharge; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Based on previous research [16], we further explored the relationship between FFA levels and AF recurrence after radiofrequency ablation. Our main findings were as follows: (1) increased FFA levels within 1-year post-ablation were closely associated with AF recurrence; and (2) increased FFA levels at 3-months post-ablation can be used as an independent predictor of recurrence.

With the maturity of the catheter ablation technique, the success rate of AF ablation has steadily improved; however, recurrence after ablation remains an urgent concern [17, 18]. Although recurrence does not completely represent long-term success rate, it is helpful in guiding subsequent treatment selection [19]. Studies have reported that FFA levels increase in patients with AF, suggesting that FFA may be associated with AF; however, its role in AF, particularly after radiofrequency ablation, has been insufficiently studied.

FFA are a direct source of substances and heat decomposed into neutral fat under physiological conditions [8]. FFA have a low blood concentration and are an important energy source for the human body [20]. Under pathological conditions, high FFA concentrations result in cellular and tissue toxicities [21], which can aggravate damage after myocardial ischemia and affect heart function independent of atherosclerosis [22, 23].

The main substances of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) produced by cardiac aerobic metabolism are FFA and glucose, which account for 60–70% of ATP generation [24]. Under physiological conditions, the glucose and FFA pathways maintain a relative balance, characterized by metabolic competition [24]. Blood FFA levels are an important factor in maintaining this equilibrium [25]. Elevated FFA levels may induce metabolic changes in myocardial energy substrates [26]. Compared to glucose, FFA require more oxygen to produce ATP [27]. Accumulation of long-chain acetylene and H+ in the myocardium results from an increase in the FFA oxidation pathway, which can directly impair cardiac function and damage the myocardial cell membrane [28]. Previous studies have shown that changes in energy substrate metabolism are associated with early impairment of left ventricular diastolic function [29]. Animal experiments have also shown that elevated myocardial FFA levels promote excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, mitochondrial damage, and cardiac dysfunction [30].

The hypothesis that myocardial ectopic lipid deposition caused by elevated FFA levels can lead to lipotoxic heart disease has been gradually accepted [31]. Animal studies have confirmed that the stimulation of myocyte fatty acid uptake causes myocardial lipid deposition [30, 32]. Previous studies have suggested that insulin resistance-related endothelial dysfunction in obesity can be attributed to fatty acid-induced ROS overproduction [33]. Studies have shown that rat heart function is negatively correlated with myocardial FFA levels, supporting that ectopic myocardial lipid deposition may be an important cause of cardiac damage in rats [34, 35]. Research has also confirmed that FFA may alter membrane ionic currents in sheep atrial myocytes, with potential implications in arrhythmogenesis [36]. An epidemiological study has linked higher circulating long-chain saturated fatty palmitic acids to a higher risk of AF [37].

Ghosh et al. [10] demonstrated that increased FFA levels lead to systemic oxidative stress, activation of the renin-angiotensin system, and cause endothelial dysfunction. FFA can damage myocardium cell membrane, impair heart function, and cause ventricular fibrillation [12, 38]. Additionally, FFA may affect membrane ion channels and potentially cause arrhythmias [39]. Consistent with these findings, our study demonstrated that increased post-ablation FFA concentration was closely related to AF recurrence. These results suggest that FFA may be a potential biomarker for predicting outcomes in patients with AF. Persistently elevated FFA levels after catheter ablation could indicate a high risk of recurrence, highlighting the need for comprehensive AF management. However, it is important to emphasize that the results of this study are preliminary.

This study has several limitations. First, this was a single-center retrospective observational study, and selection bias was inevitable. Second, the sample size was relatively small, necessitating validation in larger cohorts. Third, the follow-up period was short, limiting the assessment of long-term effects, particularly regarding secondary ablation. Finally, multiple factors may affect FFA levels, such as abnormal glucose and lipid metabolism, medication use, and genetic heterogeneity, which were not fully considered in this study. Further studies addressing these limitations are necessary to validate the findings of the current study.

In patients with AF undergoing radiofrequency ablation, elevated postoperative FFA levels were closely related to AF recurrence at the 1-year follow-up, implying that postoperative FFA levels can be used as a risk factor for predicting AF recurrence. Reducing FFA levels may be beneficial to protect cardiac function and may be used as a novel therapeutic method for the prevention and treatment of AF, or as a biomarker for predicting recurrence.

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article are available upon request to the corresponding author.

RG and SPZ contributed to the conception or design of the study. RG and SPZ contributed to the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data. RG and SPZ drafted the manuscript. RG and SPZ critically revised the manuscript. Both authors gave final approval and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of work for ensuring integrity and accuracy. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

The study was carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Shanghai Tenth People’s Hospital (No. 20210115). All the patients enrolled in the study provided informed consent. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Not applicable.

This study was supported by grants from the foundation of Yangpu District Health Commission (No. YPM202415).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.